ASSAULT FROM THE SKY

The Germans take off

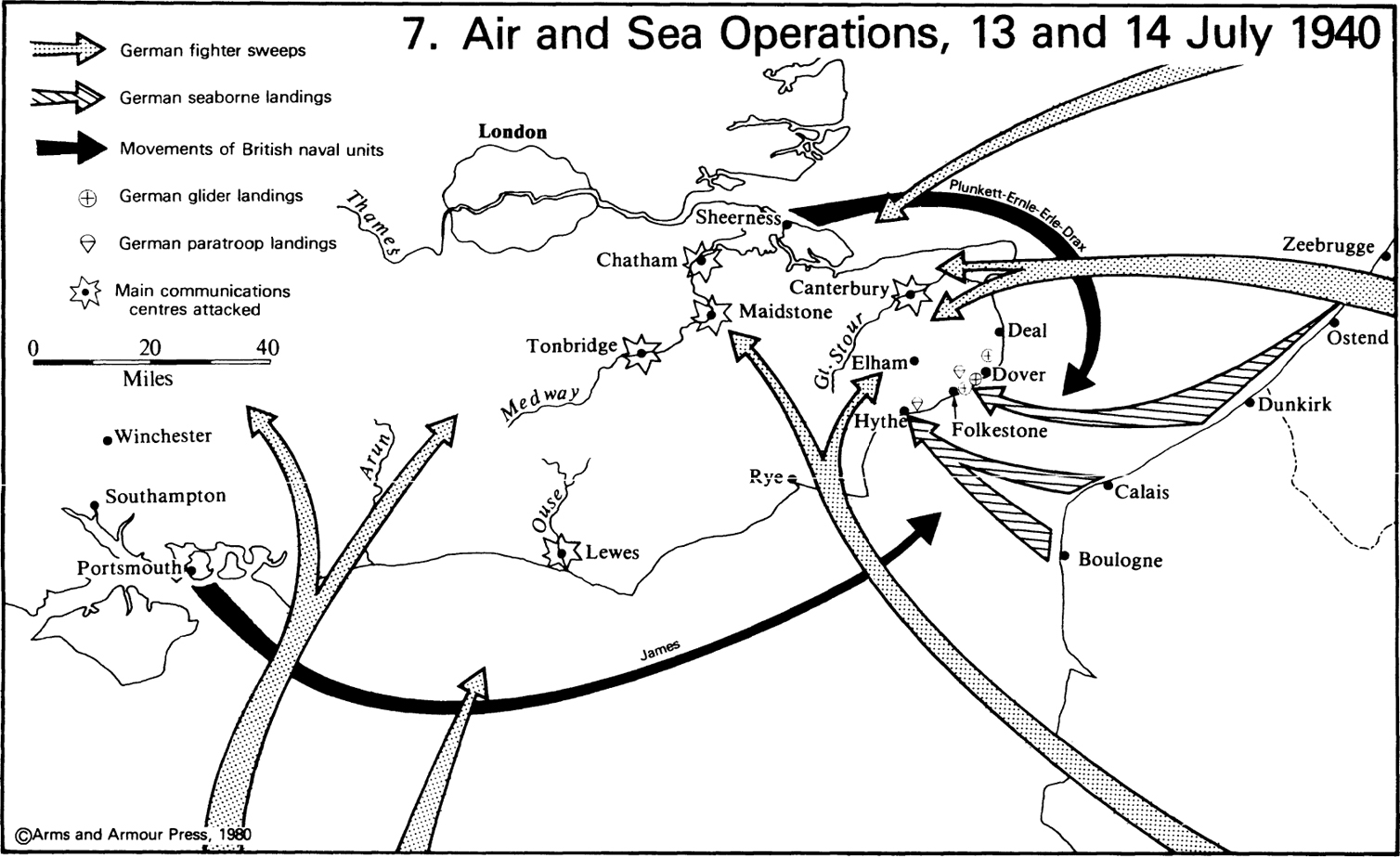

To the German glider and parachute troops who climbed aboard their machines that night, the ordeal ahead seemed no more desperate than those they had undertaken at the beginning of the Norwegian and Netherlands campaigns. Intelligent men that they were, they looked the dangers squarely in the face and reasoned that surprise – perhaps not the total surprise their leaders dreamed of – would see them through. After all, they had prevailed in Holland when surprise was lacking, so why not now against an opponent who was reckoned to be on his knees? In hope, but with nerves taut, they flew at 2,000 feet across France and Belgium in an armada routed by radio beacons to the selected dropping zones between Dover and Hythe. It was not long before the pilots began to pick out the coastline ablaze with gunfire. But visibility was clear, and the advanced guard of Ju 52s, towing the gliders, easily found their check-points.

Beneath them, the ships of the invasion fleet butted into uncomfortable seas which enervated the inexperienced passengers. The departure through lock-gates and the narrow, swept fairways outside the ports had gone surprisingly smoothly. Vessels which had put to sea in daytime had no difficulty, but those which had come out of Calais and Dover in darkness had groped their way with an air raid in progress. Some damage was done by the RAF, but none of it serious. Confusion there had been as minesweepers and Prahms failed to take up the prescribed formation, and there had been a bad moment when a minesweeper blew up on a mine. Apart from that, the sweeping went well, cutting open channels towards England through the British field where it had not been previously cleared. The craft carrying 6th Mountain Division on the right wing achieved an almost immaculate order before dusk, but those bringing 17th Infantry Division on the left were soon reduced to Formation Pigpile because of the difficulties of leaving port at night, as already mentioned. But at least this amphibious vanguard of the Wehrmacht could heave a sigh of relief that the Royal Navy was nowhere in evidence.

Glider landing

The crews of the nine DFS 230 gliders destined to arrive first on English soil and storm the Langdon Battery, had carefully studied their objective from maps and photographs, knowing full well that if this pair of modern 6in guns were not eliminated immediately, the approaching landing craft would be in dire peril. The methods adopted were like those used to subdue Fort Eban Emael on 10 May. Releasing from their tugs at 3,000 feet, below the radar cover, when 5 miles east of Dover, each glider pilot, meticulously trained to land in darkness, guided by spot lights to within 20 metres of his objective, closed the coast in loose formation.

‘I could see the white walls of the South Foreland cliffs, and fires in the town,’ wrote Leutnant Karl Hollstein of the leading glider. ‘Beyond was the clear outline of the harbour breakwater and silhouetted to the right the four tall radio masts we had been told to look for. To one side another glider loomed up and slid away. Shells from our long range artillery had been falling near the objective, but nobody fired at us as we lined up for the final approach and braced ourselves for the impact. Skimming the cliff-top, our pilot went straight at the square turrets which now became visible. Then we were down, bumping crazily and lurching sideways into what I soon discovered was a heap of barbed wire. Without a moment’s hesitation the men jumped clear and flung themselves to the ground as two more gliders rumbled to a halt almost within touching distance. At least we were not alone! I waited while the men collected their weapons, in the meantime verifying that we were, indeed, on top of our target. Somewhere not far off I heard the distinctive rattle from one of our sub-machine-guns. ‘Advance,’ I shouted, and we stood up to find ourselves, after a few steps, with the guns in front of us. It had been a miracle of navigation.’

Eight out of nine gliders lay alongside the battery, the ninth having veered right and come down among a group of 3.7in antiaircraft guns whose crews recovered swiftly from their surprise and killed all the Germans within ten minutes. But the pre-occupation of the gunners with this private battle gave the Germans at the Langdon Battery a free hand. Penned within their steel and concrete emplacements, the coastal gunners below ground were only vaguely suspicious of something wrong outside, while those in the open were shot down or rounded up. Within five minutes the area was cordoned off by glider infantry while the engineers, dragging with them 2½ tons of explosives, including cavity charges which, when detonated against the casemates, could penetrate and kill or incapacitate those inside, and set fire to inflammable material. Hollstein’s glider had touched down at 0300 hours as the grey of dawn showed in the east. At 0320 hours, the cavity charges and the explosives draped round the 6in guns’ barrels began to go off.1

With their primary task completed it was time now for the glider men to escape as best they could, skirting round Dover in the hope of joining the main German forces. Yet even now they continued to influence the main blow before it had been delivered, for it was the aggressive presence of these intrepid and victorious soldiers carrying battle deep into the British defences, which sowed seeds of uncertainty among the local defenders while the main German forces made their run in. Half their number became casualties, but their timely neutralization of anti-aircraft guns, which might otherwise have made deadly practice on the paratroops’ Ju 52s, was crucial, and they also helped confuse local British commanders who were temporarily bemused by the roar of many scores of aircraft and a plethora of reports of hundreds of paratroops descending in a huge triangle bounded by Dover, Canterbury and Ramsgate. The latter, of course, were the dummy parachutes dropped by the glider tugs as they completed their mission. It would be several hours before the effects of this deception had entirely worn off.

Unable to disentangle fact from fantasy, and chronically sceptical, as a result of recent experience with wild reports about parachute landings, neither Thorne nor Liardet were willing to commit their mobile reserves until the position had been clarified. As they waited the Germans arrived in strength. And as the 7th Air Division began to jump, the countryside rang once more to the peel of church bells as one local leader after another at last saw real paratroops, and this time spread the news with terrifying intonation to a population keyed up by anticipation.

When Hollstein was landing at Langdon, the remainder of the glider force, plus the special Storch parties, were also touching down. Not everywhere did the gliders land with spot-on accuracy. Of the ten meant to land alongside the Citadel Battery, with its big 9.2in guns, one overshot and crashed near the Castle and two others came down on the steep slope by the King Lear public house, where the Irish Guards fought back with every weapon to hand. In consequence, the 9.2in gunners were left unmolested, except for those who joined in the local fire fight as gliders landed nearby. But, as on the other side of the town, vital AA guns were diverted from their main task, leaving only the four guns at Far-thingloe Farm and the two at Buckland to engage the myriad legitimate targets which were about to present themselves.

Sergeant R. J. Turnhouse of the Royal West Kent Regiment, one of the few survivors from the battle of the cliff-tops, recalls the arrival of the gliders at Aycliff and Lydden Spout.

‘My platoon was spread out between the Abbot’s Cliff and Shakespeare Cliff railway tunnels and I was about to call them to stand-to when a sort of black shadow seemed to pass close overhead. I thought it was my imagination playing tricks, for we had been shelled all night and had got little sleep. So I called my officer and told him what I had seen. There was by now a commotion coming from the direction of the Citadel and a lot of engine noise, and we were hoping for daylight so that we could properly see what was going on. People were moving about on the open downs behind us and there was rifle and machine-gun fire up by the Citadel, and beyond, in the direction of the Castle. Then there was firing over by Lydden Spout and we began to wonder if the invasion really had begun after all the false alarms with the church bells the previous evening. My officer told me to take a Section and go to Lydden Spout to see what was going on, and so I started out along the cliff path. We had not gone far, and it was getting lighter, when some men jumped out of a patch of scrub and the next thing I knew there was firing and two of my blokes cried out. I ran and went full tilt into a big bloke who lashed out at me. I still had my rifle and I struck him back and he fell. I could see now he was a German, so I shot him as he lay on the ground. They were all around and I could see, too, a number of aircraft which must have been gliders because they landed so silently. At that moment some LDV chaps dashed by shouting there were Germans everywhere and there was nothing to be done. I was on my own and decided they were probably right. So I joined them running towards Dover where I hoped I might be of some use.’

At trivial cost to themselves the German glider troops had, indeed, seized the cliff tops from Aycliff to Abbot’s Cliff and in so doing had won command of the beaches below where 6th Mountain Division was soon due to land. The British troops who had occupied the emplacements on this sector had been overwhelmed by sheer surprise. Those few at Lydden Spout who had found time to use their weapons had held out for 15 minutes and performed the duty prescribed by Winston Churchill, ‘to take one with you’. But so swift had been the envelopment of the British position that no coherent reports had been passed to local headquarters. Here, as elsewhere, the British commanders could only surmise that the important cliff re-entrants might be in enemy hands, ready for climbing by men coming ashore below.

Even as the final shots of Lydden Spout rang out, and the battle for the Citadel paused while both sides tried to think what to do next, the Feisler Storches were setting down daintily on fields well inland, attempting to deposit the hopeful parties of Infanterie Regiment Grossdeutschland at points whence they could interrupt the movement of enemy reserves. In an arc from Ringwould, in the east, to Barham and on to Elham in the north and back towards the coast at Sellindge, these small ambush and demolition parties did what they could to make their presence felt – and largely failed except by acting as yet another diversionary factor. For the objectives such as bridges and junctions, which they sought to seize or damage were the spots best guarded by troops and LDV and, by now, the British were fully alert, stirred up by the noise of battle resounding from Dover. Some 18 Storches were destroyed as they landed and several more were shot down or damaged as they sought to escape. Other Grossdeutschlanders were hounded to death. Nevertheless, the railway from Canterbury to Dover was cut in a couple of places, as was the one from Ashford, while isolated blocking positions on a few country roads helped delay the transfer of troops belonging to 2nd (London) Brigade.2

The parachute landings – West Hougham

Attention, in any case, was now fixed upon the sea front between Dover and Hythe, whence the thunder of aircraft engines in unprecedented volume was predominant in a dawn that was vibrant with noise. Flying low and skimming the beaches, Messerschmitts recommenced the strafing they had left off the previous evening, shooting up everything suspicious near the parachute dropping zones. In their wake came Ju 88s to bomb the known British gun positions and strong points, particularly in the vicinity of Hythe as well as on Lympne and Hawkinge airfields. These came and went unopposed, the RAF fighters inland having yet to leave the ground. But when the RAF did arrive the scene was unlike anything experienced before. Close upon the heels of the bombers and fighters flew the stately mass of Ju 52s, winging their way in three dense streams at a height of 150 feet, each Staffel of 12 aircraft broken into four Vies, each transport with 12 men poised to leap into space at the end of his static line.

Braving the surviving Dover anti-aircraft guns and those of Folkestone, the seemingly endless procession of Junkers cruised ponderously over their dropping zones in the half light, cascading paratroops and weapon containers. Here and there, a crippled Junkers staggered out of formation or plummeted to earth in flames, but the torrent poured through, unchecked, to deliver their cargoes in safety. Tightly bunched for organized combat, each ‘stick’ hastened to find and broach the containers which held their heavier weapons, reserves of ammunition and radios. Within a few minutes, the flat, open spaces to the north of West Hougham and the west of Capel le Ferne seethed with smocked figures from 19th Parachute Regiment, carrying out the task of consolidation, while the airborne engineers set about clearing the ground to receive the next wave of aircraft which would land with the heavy 37mm anti-tank guns, the mortars and the 75mm field guns together with their ammunition.

The parachute landings – St Martin’s Plain

Only to the north of Hythe, where the 20th Parachute Regiment came down, was there a set back. Because it was difficult to distinguish the dropping zone to the north of Saltwood, the leading Staffel commander was a fraction too late giving the signal to jump. The first ‘sticks’ were thus carried farther north than intended, with the result that those Staffels behind became confused. 2nd Parachute Battalion, which should have landed around Newington, was scattered towards Arpinge and immediately found itself at grips with a company of 1st London Rifle Brigade (1st LRB). Meanwhile, 1st Parachute Battalion found itself dispersed between Sandling and Postling while the 3rd, which was meant for Sene Golf Course, lay dotted across St Martin’s Plain, with little more than a company actually on the proper objective. Here, on ground hallowed by successive generations of British infantry, both sides fought for survival.

The CO of 1st LRB, quick as he was to hear where the enemy were landing, drew the conclusion that both Lympne and Hawkinge constituted the enemy objective. Appreciating that there was nothing he could do at once about Hawkinge, he decided, as a preliminary, to eliminate the threat to Lympne, telling his engaged company at Arpinge to hold on while he sent the rest of the battalion to its relief. 1st LRB moved with commendable speed and caught several paratroopers in Postling before they had gathered all their weapons and organized for defence. Securing the village, 1st LRB pressed up hill in the direction of the wood at Postling Wents and Sandling Station. In the wood a company of paratroops had collected and here a fight took place between enraged but inexperienced British infantry and the annoyed, battlepracticed 1st Parachute Battalion – a small arms encounter since neither side yet had artillery support. 1st LRB stumbled into hot machine-gun fire and stopped. The sound of firing attracted more paratroopers to the scene and they widened the defences as the British tried to mount a fresh assault combined with flanking movements. But they were too slow. Within 20 minutes, such numerical and moral superiority as 1st LRB may have enjoyed at the start had dissipated. Suffering heavy casualties, they withdrew to the high ground above Postling to await reinforcements – above all, for their artillery which was still far away to the north – and dug in.

Meanwhile, 3rd Parachute Battalion endured the same difficulties as had 1st LRB. With one company pinned to the ground among the fairways, greens and bunkers of Sene Golf Course, and the rest of the unit assembling under a drizzle of fire from enemy outposts surrounding St Martin’s Plain, they were compelled, in an attempt to seize their main objective on the high ground overlooking Hythe, to attack the well-emplaced British before they had possession of their full strength or armoury of heavy weapons. Moreover, they were slow assembling their communications equipment with which to contact the bombers and cross-Channel guns which, alone, might bring to bear the heavy fire support they needed. Their casualties mounted whenever they tried to advance: the defenders of Saltwood Castle, the Club House and Sene Farm were not to be budged. Moreover, these key positions were being steadily reinforced by the Shorncliffe Garrison commander out of his reserves in Folkestone and also from a few sub-units withdrawn from the sea-front between Sandgate and Hythe. But as Major A. J. Stovold put it:

There we were, guarding the 19th hole, facing inland, with our backs to the sea we were supposed to be watching – well knowing that, at any moment, the Germans might arrive by boat. But what else could we do with such weak forces as were at our disposal? I suppose we all guessed how hopeless it was and that killing as many Germans as possible would not make much difference. But kill Germans we did, and with a will! ‘

Despite the partial failure at Saltwood, the German airborne troops had gained nearly all their objectives by 0430 hours. Between West Hougham and Capel le Ferne they had, indeed, performed better than the most optimistic among them could have desired. Within 30 minutes of landing, the commander of 19th Parachute Regiment felt sufficiently satisfied to call for the first waves of Ju 52s to land on the air strips being prepared in the midst of his dropping zone. It was a decision not without risk, even though the fields had been cleared of what few obstacles had been in the way. The danger now lay in the air and not on the ground. RAF fighters had begun to appear shortly after the landing, and already six Ju 52s on their way home had been chopped down. But these fighters, in their turn, had been punitively tackled by the Messerschmitts and, for the moment, it seemed reasonable to hope that the sky above could be kept safe for the following waves of vulnerable transport aircraft which, it had always been accepted, would be in peril. It was a calculated risk on the Germans’ part, and one taken by Kesselring in the belief that the sheer density of his bombers, fighters and transport aircraft, operating in a relatively restricted area, would saturate the defences.

The RAF strikes back

It did not need the British Chief of Air Staff’s insistent directive to make Dowding realize, immediately the report of parachute landings came in, that the time for holding back his fighter forces had passed. Expecting rich pickings among slow Ju 52s, he ordered Numbers 10, 11 and 12 Groups to throw in everything they had. In general terms the Spitfires were to tackle the enemy fighter escorts, the Hurricanes to deal with the transports while even two squadrons of Boulton Paul Defiant twin-seater fighters, which had proved too vulnerable in daylight operations, were committed to the fight. At the same time, the 24 Blenheims of Bomber Command, which were permanently on call in an anti-invasion role, were sent up under orders to find and bomb the invasion craft at sea. Thus a potentially mighty collision of air power was set in motion over the Straits of Dover. Within a period of ninety minutes, approximately 3,000 aircraft were to enter an area 30 miles square and 15,000 feet high.