CHECK AND COUNTER-CHECK

Tanks advance

When the weird mixture of tanks, armoured cars and trucks of 20th Armoured Brigade arrived at, respectively, Canterbury and Ashford en route for battle, they found orders awaiting them to probe ahead in order to make contact with the forward elements of 1st (London) Division, as a preliminary to the attack by the tank brigades which had yet to put in an appearance. Unit and sub-unit commanders had travelled in advance of the main columns and by 0700 hours were up among the defenders of the line Womenswold to Stowting, endeavouring to arrange for the projected attack. An hour earlier, the infantry had repulsed German patrols, and the guns of 1st (London) Division were firing desultory shots at parties of Germans which could sometimes be seen on the ridges beyond and attempting to infiltrate into the valleys below. To the sound of air battles and in the knowledge that it must be between three and five hours before all the tanks had reached their forming-up areas, the tank officers laid their plans – and found at the outset that the units of the London Division with whom they were to collaborate, and which had fallen back before German infiltration during the night, had only the haziest idea of the local situation, let alone how to cooperate with tanks.

It came as a surprise to the tank crews that, even in daylight, they were scarcely troubled by air attacks – this despite the spectacular air battles going on overhead. They were, of course, witnesses of Kesselring’s all-out attack upon the Sector Airfields, and those few of his aircraft which took the opportunity to fire at ground targets did so only as a diversion from their main occupation of destroying Fighter Command. The 62 tanks in 3rd Armoured Brigade which concentrated north-east of Barham at 1100 hours had completed refuelling by midday. 1st Tank Brigade was secure in Lyminge Forest with 42 tanks a little later, but, due to refugees holding up its supply echelon, was not replenished until 1330 hours. Evans, who was resolved to adhere to its original twopronged advance, at 1215 hours abandoned the concept of a simultaneous attack and ordered Crocker to move at once, telling Pratt to start the moment he was ready.

Supported by two batteries of 25-pounder guns, 2nd and 5th RTR broke cover and moved along either side of the A2 at their best speed. As they passed through the lines of 1st (London) Brigade they were joined by the 8th Bn Royal Fusiliers and flanked by the light tanks and armoured cars of 1st Northants Yeomanry. Ahead, the smoke from Dover and the surrounding villages rose sadly in the air while a few distracted civilians scurried aimlessly here and there. Not until the tanks topped the Womenswold ridge were German infantry observed in the distance, and some ineffectual mortar and anti-tank fire from small calibre weapons was encountered. Accelerating, the cruiser tanks closed with the enemy and started a panic among some men of 22nd Air Landing Division who were themselves preparing to continue their advance on Barham and Canterbury.

If the British attack had come sooner it might seriously have embarrassed the Germans. As it was, von Vietinghoff’s regrouping of formations had proceeded sluggishly due to shortage of transport and the reluctance of divisional and battle-group commanders, who had made spectacular gains with only light forces during the night, to release tanks and guns to each other for fear of exposing their already thin defensive positions to even greater risk. It took some forceful talking by the corps commander to have his way, and it was not until after midday that a centrally-placed armoured reserve of 60 tanks was assembled at Hawkinge, and a line of 88mm dualpurpose guns pushed forward to the outer perimeter of the bridgehead. Things hung by a shoe-string. Some tanks and guns, together with fuel and ammunition, had gone to the bottom under the Royal Navy’s guns and through bombing, but a great many more had been diverted in their ships to the shelter of the French coast and were only now in transit again. Although it was the intention to advance and keep the situation fluid on the 15th, most German commanders tended to hold back to establish solid defended localities until truly effective air, artillery and tank support could be produced – as was then far from the case.

Thus Crocker’s 3rd Armoured Brigade found itself tackling thin enemy defences which were occupied by jittery men. Air reconnaissance reports about the approach of massed tanks unsettled the Germans so that, when the lightly armoured British tanks did appear, the 37mm anti-tank gunners were inclined to shoot wildly and give up readily. They scored very few hits and were rapidly by-passed by the British who plunged eagerly in the direction of Dover. Not until 5th RTR. after negotiating the valley south of Barham and nosing through Denton (which had previously received a pre-planned concentration of 25-pounder fire), came out into the open were they checked. But there the 37mm gunners, stiffened in their resolve by the recent arrival of four 88mm guns, stuck it out. When the leading cruiser tank burst into flames and another had its turret knocked off by an 88, the British tank commanders came on more cautiously, feeling the way ahead under cover of dead ground and smoke – but to little avail. Encouraged by their initial successes, the fire of the German guns became devastating. The leading squadron lost half its tanks in a three-minute shoot-up and the advance came to a halt. Attempts to push another squadron round to the west were abortive and costly. Further movement was abandoned in the hope that artillery fire might eliminate these terrifying guns while 2nd RTR applied leverage by its, as yet, unchecked advance on the left.

Aided by some badly-needed luck, and helped by excellent use of the close country to the south-east of Womenswold, where the German forward defences were least well-developed, 2nd RTR cared not, at first, that neither the infantry nor the attached artillery observer failed to keep up. The tanks had it all their own way. Veering to the eastward to avoid the German guns which were known to be defending the high ground on either side of Lydden, 2nd RTR swept through Waldershare Park and headed for Whitfield, wreaking havoc as they went. Germans who were facing east were suddenly told to face north, while guns from the outskirts of Dover were pushed into position above the Buckland Valley and 30 tanks told to move post-haste from Hawkinge to Lydden. It was at this moment that von Vietinghoff also began to receive reports of still more British tanks debouching from the woods opposite Elham and Lyminge, seemingly with the intention of striking at Hawkinge. These, of course, were the heavily armoured Matildas of 1st Tank Brigade, which began their assault in two columns shortly after 1500 hours. They began their advance just as 2nd RTR was starting to hit heavy resistance for the first time near Whitfield and beginning to realize that, due to lack of support, further progress into the built-up areas was improbable. The fire directed against 2nd RTR was of a desperate intensity – the sort which causes superficial damage to machines but which deters men from charging into its midst. Although four tanks entered Guston, little more than two miles from Dover, their commanders felt quite unable to go farther until something was done to give them infantry and artillery help. So 2nd RTR, with the concurrence of Crocker, attempted to maintain a threat to the eastern German flank, while endeavouring to bring pressure to bear against the enemy guns near Lydden in the hope of eliminating the resistance to 5th RTR.1

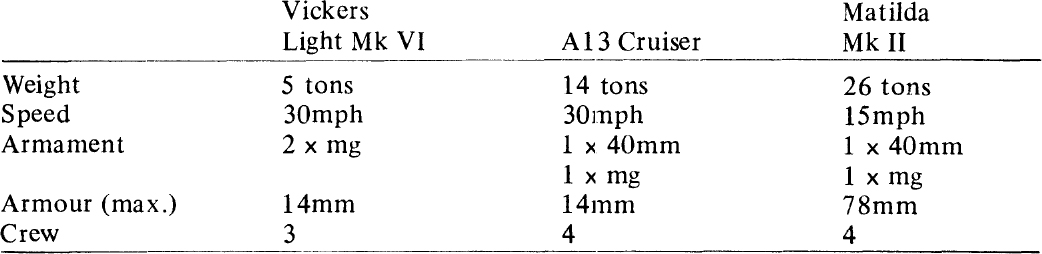

British Tanks involved

The attack by Pratt’s 1st Tank Brigade was less spectacular than that by 3rd Armoured Brigade. Moving at a ponderous and yet inexorable gait, they crossed the valley, brushing aside resistance as they climbed to the crest-line ahead. German 37mm antitank gun crews which stayed to fight, saw their shot bounce harmlessly off the Matilda’s thick skins. What was more, as the tanks reached their first objective, the crews had the pleasure of finding that infantry from 2nd (London) Brigade were close behind. Four miles away, the enemy landing zones were denoted by transport aircraft landing and taking off. For the first time in its history, the élite 7th Air Division found itself beset by a foe who seemed unstoppable, and even these fine troops began to give ground at a rate which did not meet with their leader’s approval. With sinking hearts the German watched the Matildas take possession of the high ground and begin to fan out – some driving due south towards the beaches at Hythe and the others, on the right, making straight for Hawkinge. But at this moment it was noticed, too, that the British infantry were no longer in as close attendance as it had been. They were engaged, in fact, in moppingup by-passed Germans in the villages and copses. As a result, the tanks of 1st Tank Brigade, like those in 3rd Armoured Brigade, found themselves nearing built-up areas when they were deficient of essential escorts and, equally upsetting, out of touch with their artillery whose observers hung back on the dominant Lyminge feature. Only the light, tracked and wheeled vehicles of the 2nd Northants Yeomanry kept up with the Matildas.

Destruction of the armour

In an arc from Densole to Postling through Paddlesworth and Ashley Wood, 88s awaited their prey, while the score of Pz Kpfw III tanks (whose 37mm guns were useless against Matildas) stood ready at Paddlesworth to counter-attack. Von Vietinghoff went there in person to direct operations, at the same time telling Generalmajor Schoerner, the forceful leader of 6th Mountain Division, to restore the situation in the vicinity of Dover. Von Vietinghoff watched his gunners open fire and saw the Matildas stagger under their blows. To the crews of 4th RTR at Elham, who had experienced this sort of treatment at Arras in May without realizing that it was 88mm guns which were reducing their tanks to scrap, the sensible solution seemed to be to pull back and try to find ways through the dead ground to the north. But this proved difficult and slow. 8th RTR, whose first time in action this was, tried to press-on regardless of the cost, and lost a squadron in ten minutes in front of Lyminge. The rest of the regiment swerved under the lee of Postling Wood, and with the help of 2nd Northants Yeomanry, managed to knock out a couple of 88s and punch a hole in the German ring at the boundary between the 7th Air and 17th Infantry Divisions. Shortly, a few armoured cars and the better part of a squadron of Matildas were crossing the railway near Sandling Station and rumbling towards Saltwood. They had come to grips with German defenders before news of this breakthrough reached von Vietinghoff and prompted him to dispatch ten of his reserve Pz Kw Ills to the rescue. Yet these arrived when the battle was already decided. German infantry, by firing everything they had at the British vehicles, were able to set fire to kit strapped on the outside of the Matildas and destroy a number of the Yeomanry’s thinner-skinned machines. Even so, a solitary Matilda and two light tanks waddled up to the banks of the Royal Military Canal and caused immense alarm and some damage to German troops and equipment on the beaches before a hastily laid mine immobilized the Matilda and the light tanks were knocked out. The handful of light tanks and armoured cars prowling around Saltwood and Sene Golf Course remained a threat but had lost momentum.

As these dramatic events were taking place, Schoerner was leading his divisional reserve (II Battalion 143rd Mountain Regiment) to link up with the 30 Pz Kpfw IIIs at his disposal, prior to throwing them in a north-easterly direction across the A2 road in the direction of Eythorne. The tanks ran straight into 1st (London) Brigade as it was trying to catch up with 2nd RTR, their appearance producing a dreadful effect upon the British, whose anti-tank defence consisted only of anti-tank rifles and the guns of a couple of cruiser tanks which had fallen behind the others. Within 45 minutes, the tanks had been destroyed and the infantry were prisoners or in flight. Schoerner, quick to exploit his opportunity, now sent off his tanks in a south-easterly direction to fall upon the 2nd RTR. Between Eythorne and Whitfield the opposing tank forces collided. Their machines were roughly equal in performance; the German slightly out-numbered but concentrated; the British surprised, spread out, still trying to find a way into Dover. Crocker, who was up with the commander of the 2nd, narrowly escaped capture. As for the 2nd, it fought as best it could after recovering from the initial shock. But gradually its casualties mounted until, shortly before last light, with only eight tanks left in action, orders were received to pull out to the north if they could.

The 1st Armoured Division retained a useful portion of its strength even though it had suffered nearly 40 per cent casualties in machines. As an offensive weapon it was, however, blunted, and prey therefore to the pressures applied by local British infantry leaders who wanted nothing better than to have tanks with them, dotted along the front. Both Crocker and Pratt resisted this strongly, and with some success, but of the machines which survived at nightfall, only a proportion managed to rally next morning in readiness for their next task.

An important victory

Only slowly did it dawn upon the Germans that they had won an important victory. At the height of the battle, von Vietinghoff had sent an anxious signal to Busch in France, stressing the need for reinforcements and, above all, the provision of heavy air support when the British renewed their attack. Busch was satisfied that the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe were doing everything possible to send men and material across and that, with the withdrawal of the Royal Navy, the movement of supply ships had recommenced. But he made it clear in person to Kesselring that, no matter how important it might be to complete the destruction of the RAF, that would be pointless if, due to lack of air support, the Army in England was overrun.

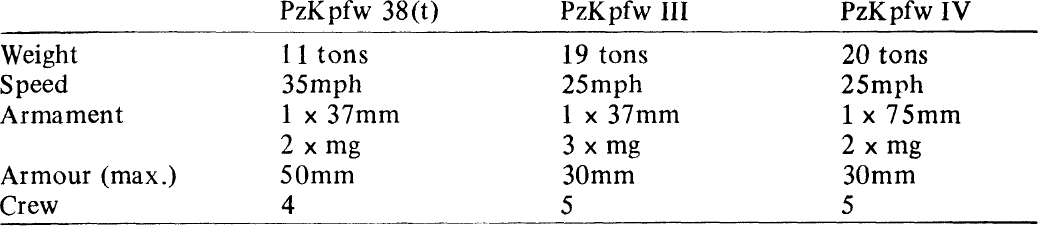

German Tanks Involved

Kesselring, who was well aware of how finely-balanced was ‘Sea-lion’s’ future at OKW, was as yet unsure how well his battering of Sector airfields had worked, and was beginning to feel concerned about the state of his Staffeln, all of which were being overworked, was sufficiently impressed to pilot Efcusch in person to Hawkinge in his Storch. There they were relieved to hear von Vietinghoff put their worst fears at rest with the news that the British counterattack had been contained. But he thought they would try again, and he explained the paucity of his reserves and how Schoerner had used up his last resources, and lost 20 out of 30 tanks in the fierce tank battle. Busch joined in, saying that the Straits would probably again be closed that night and that, therefore, the Army would be stretched thinner than ever. If more heavy equipment could not be got across, Kesselring must substitute for it with bombing. As a fine and experienced soldier himself, Kesselring was sensitive to his colleague’s anxiety. He promised full dive-bomber support next day, taking heart from a message just handed to him which said that the RAF fighters were undoubtedly far fewer in number and that their Controllers were repeatedly ‘off the air’. This seemed to indicate that the Sector Stations had suffered.

As indeed they had. The bombing had caught aircraft on the ground, demolished important repair facilities and smashed control rooms and communication links. With their numbers depleted and their control facilities crippled, the fighters lost heavily. As the day wore on, Dowding was forced to tell 10 and 12 Groups that they could no longer depend upon 11 Group and that, in the near future, the whole system of Home Air Defence would have to be put on a different footing. Fighter Command, Dowding said, could no longer provide a shield for British cities if it was also to help the Services in the sea and land battles. In actuality, as he knew, all hope of deterring the Luftwaffe through punishing losses was gone. The RAF, itself, was finding it hard to survive.

The chief limitation Kesselring placed on the use of the dive-bombers in support of the Army next day, was that they should be used only against enemy mobile forces and not in support of local infantry operations. Something had to held back to deal with the Royal Navy if it intervened again in daylight. But it was heartening, when he and Busch flew back, to see below in the fading light, the shapes and wakes of sea transport making for England, and to know that some vital equipment must reach their destination. Nowhere on either flank could be seen any sign of the Royal Navy.

The sense of optimism generated by Kesselring and Busch arrived too late to affect the vital meeting at OKW at 1300 hours on the 15th, when the decision to proceed with or cancel ‘Sealion’ was debated. By then, a much more complete picture of the situation had been assembled compared to that of the 14th. Furthermore, news of the commencement of the British armoured attack had not yet come through to disturb composure. That the lodgement was well made, if somewhat insecurely based, was no longer in doubt, as von Brauchitsch proudly explained. And both Raeder and Goering were now hopeful. The unexpected reduction in activity by the Royal Navy allayed some of the anxiety, while the hope that Kesselring’s attack on the Sector Stations (as yet unassessed in its effectiveness) might finally win air superiority, were factors in favour of continuing. But it was Keitel who made the vital contribution, briefed as he now was about the consequences of withdrawal should it be demanded. The Conference Minutes put his case in a nutshell:

General Keitel said that under adverse conditions on the sea and in the air it would be even more difficult to evacuate the land forces than it would be to go on trying to maintain them. In point of fact, the existence on English soil of some four German divisions meant that the Wehrmacht had passed the point of no return.

Reader remarked in his diary, with wry amusement, that Hitler seemed to blink at this bare assertion. But he had no adequate reply – ‘and so we persevered and carried on worrying.’