2

Metrical Tension and Varieties of Voice

WORDSWORTH’S METERS AND COLERIDGE ON METER

Wordsworth’s emphasis on the “pleasure arising from the perception of similitude in dissimilitude, and dissimilitude in similitude,” leaves ample room for—and even requires—a metrical practice exhibiting a wide variety of relationships among diction, syntax, and metrical form and verse pattern. Wordsworth was as much interested in the poem as a locus of active tensions between competing powers as he was in it as a locus amoenus characterized by achieved balance and harmonious unity of complementary elements. Wordsworth’s poem is a Garden of Adonis, not a Bowre of Bliss.

The poet’s meter and his selection of diction are distinct elements, yet are capable of being “exquisitely fitted” to one another. Meter functions as an external source both of fixed laws grounded in physicality and of passions produced by recollection of previously encountered works of art. It serves both as a force that, by resisting individual freedom and variation, makes such freedom and variation possible and as a standard against which the variation so produced may be recognized as significant. According to Wordsworth’s theory, metrical form may be subordinated to the “passion of the sense,” functioning primarily as an expressive reinforcement of the speaker’s passions and habits of association. But it need not be. In fact, Wordsworth’s discussion and practice suggest that he regarded such fitting as the exception to the rule—useful in the delineation of a particular frame of mind but not the exclusive aim of the poet’s art at all times. More often than not meter participates in the creation of a complex sense of the poem as an “intertexture” of potentially opposing elements. The passion of meter can and does provide a type of “interference” that heightens and improves the “coexist[ing]” pleasure produced by the passion (Prose 1:145). In Wordsworth’s view, therefore, writing in meter does not require any one kind of diction, nor does it impose rigid requirements on syntactic elements. All that is required is an original and dynamic relationship between the two patterns of organization sufficient to encourage and sustain active and pleasurable reading.

Given these attitudes, it is no wonder that Coleridge found the discussion of meter in the Preface unsatisfactory. Wordsworth’s ideas concerning metricality and “similitude in dissimilitude,” despite superficial similarities with Coleridge’s ideas about the “reconciliation of discordant elements,” are seriously at odds with Coleridge’s own specifically organic theories, all of which flow from his view of the harmonious poem as a self-contained “unity” in which “all of the parts … must be assimilated to the more important and essential parts” (BL 2:72).1 For Coleridge, the passion of the meter originates in “the balance in the mind effected by that spontaneous effort which strives to hold in check the workings of passion.” It therefore follows that “the elements of metre owe their existence to a state of increased excitement,” and that the language accompanying meter’s signal of this “state” ought also to be the language of “excitement” (2:64). Whereas Wordsworth’s theory emphasizes the “intertexture” of often-conflicting elements arising from different sources, Coleridge holds that there ought to be a complementary balance and correspondence between the excitement produced by the meter of a poem and that produced by the diction.2

Coleridge’s conception of the poem as a unity and balance of formal elements stems from and is of a piece with his definition of the poet as one in whom excitement produces an extraordinary degree of imaginative, specifically synthetic, activity:

The poet, described in ideal perfection, brings the whole soul of man into activity, with the subordination of its faculties to each other, according to their relative worth and dignity. He diffuses a tone, and a spirit of unity, that blends, and (as it were) fuses, each into each, by that synthetic and magical power, to which we have exclusively appropriated the name of imagination. This power … reveals itself in the balance or reconciliation of opposite or discordant qualities. (2:15–16)

It is precisely this extraordinary power to subordinate parts to wholes that is lacking in the speech of any speaker other than the “Poet” (and particularly so in the speech of the common man, who is the source of Wordsworth’s “real language”): “There is a want of that prospectiveness of mind, that surview, which enables a man to foresee the whole of what he is to convey, appertaining to any one point; and by this means to subordinate and arrange the different parts according to their relative importance, as to convey it at once, and as an organized whole” (2:58). It follows that a good poem, which Coleridge defines as “that species of composition, which … is discriminated by proposing to itself such delight from the whole, as is compatible with a distinct gratification from each component part” (2:13), cannot be the result of the kind of genuine and frequently unresolvable tension between diction and meter that Wordsworth conceives to be a chief effect of arranging “real” language in meter. Such a theory, argues Coleridge, could not have been behind the composition of those of Wordsworth’s poems that are singled out for praise in Biographia Literaria as supreme examples of the operation of that “synthetic and magical power, … imagination”; rather, the theory has led Wordsworth into the composition of such “failures” as “Alice Fell,” “Anecdote for Fathers,” and “The Sailor’s Mother,” in which the presence of meter only heightens the unredeemably prosaic character of the poems.

As I sought to show in the preceding chapter, everything about Wordsworth’s own theory and practice suggests that he never regarded this Coleridgean drive toward synthesis and unity of diction and meter as the exclusive aim of his verse. Indeed, Wordsworth does not merely acknowledge what Coleridge calls “inconstancy” of style; he embraces it as an integral part of what he takes to be the poet’s chief task. That task is the imitation—for the purposes of providing a kind of pleasure that may induce sympathy and aid understanding—of the fullest possible range of the manifold operations of the mind under the influences of various passions. What Wordsworth calls tracing the “fluxes and refluxes” of the vastly complex human mind does not merely admit of a wide range of accommodations between diction and meter; it demands it.3

Wordsworth certainly regards the preeminently imaginative mind in its highest pitch of excitement (the Coleridgean ideal poet) as an important—perhaps even the most important—subject for his poetry. And in poems or parts of poems that aim at the “surview” of which such minds under such conditions are capable, the appropriate interrelation between diction and metrical form will be a blending or fusion of discordant elements. The harmonious unity of metrical form, elaborate syntax, and sonorous diction will suggest in such cases that there is indeed something natural and inevitable about the conformity of the language to the overarching structures of an organizing and unifying intelligence. At the same time, Wordsworth’s theory— and Wordsworth’s poetry—is everywhere attuned to the fact that most human minds at most times (and all minds at some times) lack for one reason or another this imaginative and preeminently poetic surview. Wordsworth’s verse contracts (or expands, depending upon one’s perspective) to encompass the distempered mind of the Mad Mother as well as the “mind of Man” celebrated in the peroration of The Prelude as “a thousand times more beautiful than the earth / On which he dwells” (14-Bk Prelude 14.450–52). The bewildered cries of the speaker of “The Last of the Flock,” the bemused and wandering narrator of “The Idiot Boy,” the playful singer of “Written in March” (“The Cock is Crowing”), and the sententious rhetorician of “Humanity” are as “Wordsworthian” as the supremely synthesizing voice of “Tintern Abbey.”4 The “Poems of the Imagination,” after all, form only one of eighteen categories into which Wordsworth would eventually divide his poetical works beginning in 1815. There is place in Wordsworth’s corpus for Poems of the Fancy, Poems of the Affections, Poems Referring to the Period of Old Age, and so on. Wordsworth’s discussion of meter, with its emphasis on meter as a “superadded” element or as a “co-presence,” theoretically allows him an unlimited range of possibility in the fitting of diction to meter for the purpose of exploring a broad range of the infinitely complex processes through which mind and language “act and react” on each other.

Coleridge’s analysis in Biographia Literaria, then, may be regarded as the fullest, most philosophical description of a typically Wordsworthian relationship between diction and meter, a relationship that is, however, only one of many that Wordsworth allows in theory and explores in practice. Whereas Coleridge characteristically works from a theory based on the unifying powers of metrical arrangement, Wordsworth’s theory tends to emphasize difference and variety. It leaves open the possibility of an entire range of stylistic accommodations appropriate to the poetic delineation of “what we are.” The difference of opinion on this matter may be seen as finally of a piece with so many of the crucial differences between the two men on aesthetic and philosophical issues. The distinction made long ago by John Jones is still useful: for all that the two poets shared, says Jones, “the theme of the one [Coleridge] was unity and of the other [Wordsworth] significant relation.” Coleridge’s poet fuses, blends, and reconciles; Wordsworth’s engages in a dynamic process of fitting that only sometimes results in such significant reconciliation. Coleridge’s poem or poetic corpus is or strives to be a unified organism in which each is subordinated to all; Wordsworth’s is a “frame of things” in which what is individual, idiosyncratic, disorderly, or recalcitrant is placed in significant relation to the whole.5 Just as Wordsworth’s thematic emphasis on the processes of “fitting” mind to nature (and nature to mind) tends to emphasize the absolute importance both of the individual mind and of what resists and remains unencompassed by the individual mind, so his “fitting” of language to meter brings to the foreground intricacies in the relationship between individual motives of speech and preordained structures of relationship that are not able to be subordinated entirely to merely personal expression. Finally, whereas Coleridge’s specifically organic-aesthetic views tend to encourage a response to the poem as a self-contained object, expressive of a unity of complementary forces that inhere in the structures of the poem itself, Wordsworth’s different views tend to stress the power of the poem as a vehicle for communication between poet and reader, the end of which is the creation of an open-ended and dynamic relationship.

METRICAL FORM AND RELATIONSHIP:

THE EXAMPLE OF “THE SAILOR’S MOTHER”

It may be worthwhile at this point to discuss some of the chief points of difference between Wordsworth’s and Coleridge’s views on these matters with reference to a particular poem. Because Coleridge singles out “The Sailor’s Mother” as an especially good example of the deleterious influence of Wordsworth’s theories, that poem will serve as a convenient focus of attention.

For Coleridge, “The Sailor’s Mother” is one of a number of works in Wordsworth’s corpus that employ diction and syntax so prosaic that they “would have been more delightful … in prose” (BL 2:69). Indeed, the poem represents, according to Coleridge, “the only fair instance … in all Mr. Wordsworth’s writings of an actual adoption, or true imitation of the real and very language of low and rustic life” (2:71). Coleridge hopes to show that the combination of such diction and metrical arrangement must result in failure and bases his explanation on his own view of what Wordsworth calls the “symbolic” or “exponential” power of meter. Coleridge’s sense of this power is purposely more restricted than is Wordsworth’s:

Metre in itself is simply a stimulant of the attention, and therefore excites the question: Why is the attention thus stimulated? Now the question cannot be answered by the pleasure of the metre itself: for this we have shown to be conditional and dependent on the appropriateness of the thoughts and expressions, to which the metrical form is superadded. Neither can I conceive any other answer that can be rationally given, short of this: I write in metre, because I am about to use a language different from that of prose. (BL 2:69)

As has been suggested, Wordsworth would agree entirely with Coleridge that meter acts as a “stimulant of the attention.” He would not grant, however, that the poet must necessarily fulfill the promise to “use a language different from that of prose.” For Wordsworth, whether or not and to what extent the language of a poem will differ from the language of prose will be dictated by passion or excitement itself, not by the use and habit that meter always to some degree stimulates. Coleridge’s limitation of the proper relationship between meter and diction exclusively to a symbiotic union of complementary powers drawn from the same source (the state of excitement) implicitly dismisses as irrational Wordsworth’s view of meter. For Wordsworth, the permanent possibility that meter will provide opposition to the passion of the sense is the crucial element of the contribution that meter makes to the “complex end” of a poem. That opposition may manifest itself through the simple recalcitrance of the “passion of meter,” through the invitation that metrical forms extend to the reader to engage in comparison and contrast between the poem under consideration and other poems, or through the tendency of meter to “divest language, in a certain degree, of its reality.” In fact, it is the ability of meter to provide contrast to diction, both when the diction abounds in passion and when it (significantly) lacks it, that makes it the only artificially contrived element necessary to produce poetic pleasure. In Wordsworth’s theory, the power of meter alone frees the poet from the need to employ gaudy figures and language, gross and violent imagery or situations, or any other “colours of style” (Prose 1:145) in effecting poetic pleasure. It is only those readers who “greatly underrate the power of metre in itself” who require, in order to be pleased, that the poet employ “the other artificial distinctions of style with which meter is usually accompanied” (1:145).

“The Sailor’s Mother” confronts the reader from the outset with a markedly incongruous relationship between humble subject and elaborate stanza form. The poem describes a speaker’s account of his chance meeting with a woman who tells him a simple tale in simple words. Yet in its structure and movement and its literary associations, the stanza with which Wordsworth chose to frame this tale has nothing to do with that speech of “low and rustic life” that Coleridge says is truly imitated in the poem:

And, thus continuing, she said,

I had a Son, who many a day

Sail’d on the seas; but he is dead;

In Denmark he was cast away;

And I have been as far as Hull, to see

What clothes he might have left, or other property.6

The length of the stanza itself, and especially the concluding pentameter and hexameter couplet (which suggests Spenser’s influence), provides it with a formal integrity unusual in the stanzas of short narrative poems on subjects from common life—particularly when the narrative is as stark as Wordsworth’s is. The couplet functions as a rhythmic summation or turn, slowing the pace established by the tetrameter of lines 1 to 4 and providing in purely rhythmic terms an exaggerated sense of closure.

In fact, the structure employed in the concluding lines of these stanzas is more likely to have been associated with odes than with narrative verse in the later eighteenth century. Prior’s ten-line adaptation of the Spenserian stanza in his influential “Ode, Humbly Inscribed to the Queen” (1706) helped to establish and perpetuate the use of a hexameter close in odic stanzas.7 This use persisted at least as late as Coleridge’s “Ode to the Departing Year” (1796) and “Dejection: An Ode” (1804) and Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality” (the first four stanzas of which were composed in March 1802, the same month and year in which “The Sailor’s Mother” was composed). Gray used a hexameter close in a largely tetrameter stanza in his “Ode to Adversity” (1748), from which Wordsworth borrowed the stanza of his “Ode to Duty.”8 And a stanza identical to the one used in “The Sailor’s Mother” is employed by Cowper in his translation of Antonio Francini’s “Ode: Addressed to … John Milton” (c. 1792; published 1808). Coleridge uses the form twice in works which, though not strictly odic, are generically and stylistically more elevated than Wordsworth’s homely tale: the juvenile poem “Nil Pejus est Caelibe Vita” (1787; published 1893) and the meditative “A Day Dream” (“My eyes make pictures” [1802?; published 1828]), the latter of which refers to itself as a “tender lay” (l. 33).9

Wordsworth’s use of a much more rhythmically elaborate, insistently lyrical metrical frame than might be thought appropriate for a homely tale told in simple words would seem to be an extreme example of that “intertexture” of opposing feeling that he values as a source of poetic pleasure. The significance of this opposition becomes more apparent as one recognizes that the poem as a whole is structured according to an internal stylistic opposition: stanzas 1, 2, and most of 3 are devoted to a narrator-speaker’s account of the meeting; stanzas 4, 5, and 6 consist almost entirely of the quoted speech of the sailor’s mother. Everything about the mere mechanism of the poem tends toward a presentation of obvious contrasts.10

The speaker whose voice begins “The Sailor’s Mother” is represented by Wordsworth through a style in which speech motives and metrical imperatives are virtually free from tension:

One morning (raw it was and wet,

A foggy day in winter time)

A Woman in the road I met,

Not old, though something past her prime:

Majestic in her person, tall and straight;

And like a Roman matron’s was her mien and gait.

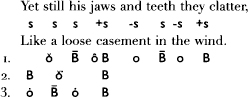

The only rhythmic complexity is the very mild sense of promotion of the word “in” in line 3:

The end-stopped lines, punctuated by full-stressed and perfect rhymes, tend to correspond to self-contained syntactical structures. Each line thus maintains its integrity while contributing to the whole. The full stop at the end of the fourth line effectively divides the quatrain from the couplet, allowing the final lines to perform their expected function as a summation or turn to the stanza and producing a satisfying sense of closure. The repetition of w sounds throughout the first three lines, the m and n sounds in the concluding couplet, and the slow pace of the hexameter describing the woman’s stately “mien and gait,” all produce a conventionally harmonious sense of pattern. Together they form a fairly elaborate texture of rhythm and sound that acts to reinforce the elements of formal composition and patterning in the description of the woman. Such details as his immediate placing of the woman within the frame of her expected span of life (“something past her prime”) or his likening of her posture and “gait” to a figure representative of a kind or class of woman known to him through art and literature (“like a Roman matron’s”) show the speaker to be predisposed toward the kind of “surview” that Coleridge identifies as the preeminently poetic movement of mind. And the particularities and structures of his language may be seen as an expression or objectification of his habitual tendency to place particular phenomena (from syllables and phrases to events and strangers met on the road) in relation to structures and patterns within which they are accorded significance beyond the particular.

In stanza 2, Wordsworth provides a different kind of evidence that this speaker’s perceptions are informed by more-than-usual powers of thought and feeling, as the plain “woman” becomes, through the effect on him of her “majestic” bearing, a proof of the survival of an “ancient Spirit”:

The ancient Spirit is not dead;

Old times, thought I, are breathing there;

Proud was I that my country bred

Such strength, a dignity so fair

(ll. 7–10)

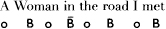

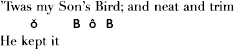

The metrical style swells with the speaker’s pride. Line 9 introduces the first real rhythmic complexity in the poem, in the ambiguous placement of “I” in the third position. The initial beat (or “first foot inversion”) would tend to encourage the demotion of “I” in a double offbeat (because of a strong expectation encouraged by the metrical set that what Attridge calls the “initial inversion condition” will be fulfilled):11

One would feel more sure of this rhythmic realization, however, were it not for the relatively weak “that” in the fourth position.

One effect of this small ambiguity is to make the initial inversion insistent; that is, the pattern B ŏ B (usually realized +s -s -s +s) is emphasized by the slight tension involved in realizing it. The pattern is one of the most common features of the five-beat line. Here it appears in a four-beat, enjambed verse followed by a strong pause after the second syllable in the following line. Taken together, these elements tend to suggest rhythms more common in the heroic line than in four-beat “native” verse and help to give the phrase (from “Proud” to “strength”) a rhythmic form and sense of weightiness appropriate to the elevation of the woman to a kind of heroic status:

Wordsworth signals his speaker’s turn of mind, then, through affective and emblematic uses of meter both: semantic elements conform easily to abstract, conventional literary structures (the line and the stanza). These elements create the music appropriate to what the speaker calls his initial “lofty thoughts” and indicate through their relationship the abstracting power of the speaker’s mind. Parts and wholes are in easy relationship. Individual sounds drop easily into patterns, as the particularized “woman” on the road becomes a walking embodiment of “Spirit.”

Neither the conventional harmonies nor the abstraction of the figure of the woman persist, however. The contrast is stark between the style of the stanzas devoted to the speaker’s speech and the style of the quotations attributed to the sailor’s mother. Her first line, in response to the speaker’s question about what she carries beneath her cloak, contains the only conventionally harmonious, patterned speech attributed to her:

A simple burthen, Sir, a little Singing-Bird.

(l. 18)

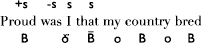

The alliteration (“simple … Sir … Singing”; “burthen … Bird”) and the restricted sonic range and repetition of the vowels give the verse a faint hint of a more songlike rhythm than has been established to this point. This effect probably results in large part from the assonance in “Sir” and “Bird,” which tends to divide the hexameter aurally into two three-beat units (a tendency that it has even without this hint of internal rhyme):

The rhythmic shift is especially apparent given the earlier use of the hexameter (stanzas 1 and 2) as an unbroken unit carrying a summation in stately tones.

The contrasts continue in the first full stanza of quoted speech:

The Bird and Cage they both were his:

’Twas my Son’s Bird; and neat and trim

He kept it: many voyages

This Singing-bird hath gone with him;

When last he sailed, he left the Bird behind;

As it might be, perhaps, from bodings of his mind.

(ll. 25–30)

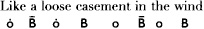

The sources of formal tension are many. Neither the individual lines nor the four-beat quatrain has any real integrity. The rhymes in the run-on lines are, as Coleridge notes, barely noticeable (2:70). The rhyme of “his”/“voyages” is particularly troublesome, as it is both imperfect (really a consonance rhyme) and what William Harmon calls “promoted”: that is, the final syllable of “voyages” requires, at least theoretically, an exaggerated degree of stress, or “promotion,” to fulfill the phonetic conditions necessary to rhyme.12 “They” in the first line is syntactically superfluous. It functions here, as so frequently in later eighteenth-century poetry, as a means for approximating colloquial speech. It may be worth noting that such devices are made effective in part through the strict syllabic constraints of the meter, since the redundant “natural” word choice also serves to fulfill a purely metrical requirement. Incongruously, the natural speech fits the metrical frame perfectly.

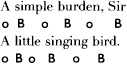

Other sources of tension include the rhythm of the second line, which introduces the first real rhythmic dislocation in the poem (a -s -s +s +s group, or what Attridge calls a “stress-final implied offbeat formation”):

This verse, leading as it does to an enjambment and a midline pause after an unstressed syllable in the next verse, asserts strongly an emerging natural speech rhythm that disrupts significantly the sense of the more formal organizational patterns of the stanza itself (and of the stanza as it had been employed in presenting the speaker’s own words). The syntax of the hexameter, with its double pause, again (as in line 18) resists the tendency of the couplet to suggest closure.13 Finally, the facile and pleasant alliteration of the initial stanza of the poem is replaced here by eight occurrences of an initial b sound, which serve to snag the rhythm (“he left the bird behind / As it might be, perhaps, from bodings”).

If Wordsworth thought that the presence in a poem of such speech, which conforms so little to the expectations of the metrical pattern, was in and of itself sufficient cause for condemnation, he could hardly have done a worse job concealing his deficiencies in the stanzas devoted to the speech of the Sailor’s Mother. If he had simply wished to imitate, unobtrusively, simple speech, he could have followed the example of many contemporaries (Burns or Southey, for example) and used, as indeed he had used in several of the Lyrical Ballads, a simple common measure stanza or tetrameter couplets. Either of these forms would have decreased the number and kinds of formal expectations and structural divisions that mark the failure of the woman’s voice to fall into line. (This is precisely what Coleridge registers about the verse when he suggests that the speech would have been better had it been in prose.) Conversely, if Wordsworth wished to soften what Coleridge calls the “abrupt downfall” (BL 2:71) that occurs in moving from the speaker’s harmonious and elevated use of the stanza into the quoted speech of the woman, he could have done so. He chose, however, to make the stylistic contrast so clear and inescapable that he forces the reader to consider the possibility that the clash of dissimilar uses of the same metrical frame is itself an integral part of the poem’s subject. What, then, might the comparative “failure” of the woman’s voice to conform to expectations signify?

The formal context in which the Sailor’s Mother speaks allows the reader the obvious opportunity to see in what ways her habits of mind differ from those of the speaker. Whereas the speaker’s stanzas are full of abstract nouns (“ancient spirit,” “Old times,” “my country,” “such strength,” “a dignity”) and adjectives describing the qualities of things (“raw,” “wet,” “foggy,” “majestic”), the woman’s diction is characterized by the use of concrete nouns (“seas,” “bird,” “cage”) and simple verbs that relate the objects of her experience to one another and ultimately to a central signifier—”my son.” Whereas the speaker’s style stands as evidence of his ability and tendency to organize his world by assimilating discrete parts of his experience within larger structures and categories, the woman’s style expresses a complete preoccupation with particularity, with hard fact couched in the simplest narrative form. Words matter to her only insofar as they point to particular facts and things; facts and things matter only as they are connected with her son.

The clash of styles in “The Sailor’s Mother,” then, may be regarded as having been calculated to bring into direct opposition the mind of the “wise man” with that of the “rustic” (the terms are Coleridge’s): one speaker is habitually predisposed to seek and “discover and express those connections of things, or those relative bearings of fact to fact, from which some more or less general law is deducible”; the other is limited to “insulated facts” (BL 2:52–53).14 Coleridge regards the concern of the “rustic” with “insulated facts” as evidence of “imperfect development” of faculties. Rustic speech is unpoetic because it issues from a mind constrained to “scanty experience” or “traditional belief.” The evidence of Wordsworth’s poem (and the burden of his theory), however, suggests that he regarded the larger relationship between the speaker’s imaginative poetic surview and the limited and concrete concerns of the woman as poetic in itself. For all of the stark differences between the two voices, they are inextricably bound to one another by the obvious fact of their dissimilar fitting to a common and aesthetically insistent stanza form. And the relationship brought out through such “fitting” works to illuminate tendencies in both of the speakers, as it invites the reader to an active engagement of the similitude lurking within the dissimilitude.

In more concrete terms, the juxtaposition of voices ensures that neither voice will quite “fit” its metrical frame seamlessly. If there is something strikingly prosaic, commonsensical, and matter-of-fact about the woman’s speech, there is also something a bit too “lofty” in the speaker’s stylized abstraction of the woman. (This point is made explicit in the speaker’s initial difficulty in reconciling his “pride” at seeing this embodiment of “ancient spirit” with the fact that she addresses him as a beggar—“I looked at her again, nor did my pride abate. / When from these lofty thoughts I woke.”) The incongruity is produced in part by the poet’s use of a metrical frame that carries associations with more elevated kinds of poetry than this. For the speaker, the spectacle of the woman carrying the caged bird has a much more universal figurative significance than that which the woman herself is capable of seeing. (In this connection, it may be appropriate to emphasize once again the Spenserian associations of the hexameter final line of these stanzas.) But the suggestion remains, too, that with gains come losses, or that his discovery of the general law of which the particular woman is an instance may not, in fact, give sufficient weight to the irreducible particularity of the woman as a “mere” sailor’s mother begging “in the road.”

Last words are important words:

“And now, God help me for my little wit!

I trail it with me, Sir! he took so much delight in it.”

(ll. 34–35)

The poem ends with quoted speech, with no rounding off or summation by the original speaker. The unimpressive rhyme of “wit / it” and the ending of the poem so baldly with a pronoun further frustrate any residual sense one might have of the couplet as the appropriate vehicle for pat summation. (Her “little wit” may have its proper formal embodiment here in the absence of a more conventionally witty coalescence of sound and sense.) But the most important emblematic metrical point to note is the hypermetricality of the final line. Its seven stresses constitute the first (and, of course, only) instance of a true formal break in the poem. The quoted speech not only fails to realize the expectation that the pentameter and hexameter couplet will provide a satisfying sense of the pattern fulfilled but also actually breaks the mold. In a very basic, physical sense, the poem signals that this seemingly restricted and powerless voice nevertheless presents a serious challenge to conventional forms of organization, represented both by the stanza and by the poem’s other, more conventionally poetic, voice. The difference between the Sailor’s Mother’s mind and affections and the mind and affections of her questioner is made a palpable, rhythmic reality. At the same time, the framing of these rhythmic differences in the same form suggests that the two ways of thinking and feeling are, properly understood, in dialectical relationship. Make the speaker’s music the defining music of the poem, and the voice of the woman is reduced to a technical mistake. Hear the music of both voices as appropriate rhythmic embodiments of different “fluxes and refluxes” of passionate minds, and a different, more comprehensive, music may emerge—full of tension, and richer than either voice alone.

Any broad surview that emerges from “The Sailor’s Mother,” then, must issue from the reader’s active participation in a dynamic poem made up of contrasts: abstraction and particularization; the heroic ancient spirit and the pathos of a simple beggar woman; the drive toward closure and the resistance to closure in the speech of the finally enigmatic figure. Wordsworth says in the Preface to Poems (1815) that “Poems … if they be good … cannot read themselves” (Prose 3:29). In “The Sailor’s Mother” he depends on the presentation of dissimilar voices in similar forms to prompt the reader to work toward synthesis of the disparate elements of the poem. The activity of reading the poem finally binds speakers, poet, and reader together and functions as a proof of Wordsworth’s assertion that the mind of the poet differs only in degree, not in kind, from that of ordinary men and women.15 The stylistic clashes in “The Sailor’s Mother” are best regarded, then, as instances of a strategy for the energetic representation of diverse minds in active interchange with the world and with one another.

A good deal of evidence exists to suggest that Wordsworth was conscious of the artistic uses of such metrical variety and dissimilarity and that he was concerned that this aspect of his technique and its principles be understood. For example, in the note appended to “The Thorn” in editions from 1800 to 1805, Wordsworth says that the meter of the poem was selected not because of its appropriateness to the speaker’s style and language but because of its ability to provide a contrast to them. Wordsworth’s aim in “The Thorn” is to delineate a type of character that, though “sufficiently common” in his experience, had not, as of 1798, found sufficient literary expression. His speaker, whom he describes as “credulous and talkative” and “prone to superstition,” is a man of “slow faculties and deep feelings.” Although he has “a reasonable share of imagination,” he is “utterly destitute of fancy.” Such minds, Wordsworth says, tend to express themselves slowly, in words that they feel to be “impregnated with passion,” whether or not those words are sufficient to convey the passion they feel (PW 2:512).

The challenge facing Wordsworth was how to portray the motions of such a mind with sufficient accuracy while simultaneously conveying pleasurable passion “to Readers who are not accustomed to sympathize with men feeling in that manner or using such language.” Toward this end, he decided to employ a type of meter more “Lyrical and rapid” than would be strictly consonant with the voice he wished to portray. He wished to make the poem “appear to move more quickly” than its selection and arrangement of diction actually allows it to move: “It was necessary that the Poem, to be natural, should in reality move slowly; yet I hoped that, by the aid of the metre, to those who should at all enter into the spirit of the Poem, it would appear to move quickly” (PW 2:512–13).

The stanza that Wordsworth chose for “The Thorn,” after an initial attempt at tetrameter couplets (see PW 2:240 app. crit.), is no more likely a choice than is the choice of an odic stanza for “The Sailor’s Mother.” It is an intricately rhymed, eleven-line structure formed by combining a variation of the ballad stanza (abc4b3) with a modified tail-rhyme stanza (deff4e3gg4).16 Although “The Thorn” marks the first use in English literature of a stanza of exactly this construction, stanzas similar to Wordsworth’s had been used before, most notably by Gray in “Ode: on a Distant Prospect of Eton College” (1747) and “Ode on the Spring” (1748).17 It is tempting to think that Wordsworth may in fact have had the example of Gray in mind when he developed this stanza. The fitting of the homely speech of a superstitious and “talkative” sea captain to a metrical frame recalling the elegant Gray has obvious ironic and revisionary possibilities, especially when it is remembered that Gray is a chief target of Wordsworth’s arguments in the Preface. Gray is the poet whom Wordsworth places “at the head of those who, by their reasonings, have attempted to widen the space of separation betwixt Prose and Metrical composition, and was more than any other man consciously elaborate in the structure of his own poetic diction” (Prose 1:133). One need not think specifically of Gray, however, to sense that the representation of the speaker’s tale is designed to be pleasurably dissimilar both from the natural speech of such men and from the kind of speech that might conventionally find expression in such a metrical form.

The note to “The Thorn” demonstrates that Wordsworth expects of its readers the same sensitivity to the relation between meter and diction as he expects of readers of “The Sailor’s Mother.” In both poems the complex intertexture of feeling supplied by the meter is a chief means through which the poet leads the reader into physical relationship and sympathy with types of minds with which he or she normally would have little or no contact. A similar emphasis is present in his discussion in the 1800 Preface to Lyrical Ballads of his choice to write “Goody Blake and Harry Gill,” which he calls “one of the rudest [poems] in the collection,” both “as a Ballad” and in a “more impressive metre than is usual in Ballads” (Prose 1:150). Wordsworth does not say that the poem is designed to be more impressive than a ballad; he says that an important element in the conception of the poem was his choice to frame a rude ballad-narrative in a meter that the sensitive reader would feel to be more impressive than usual in the genre, both because of its inherent complexities and because of its literary-historical associations.

The Lyrical Ballads themselves contain sufficient contrast between the unusual use of this “impressive” meter and a more conventionally sanctioned use. It is, and ought to be, something of a shock, at least a gentle one, that “Lines Written near Richmond, upon the Thames, at Evening” (hereafter “Lines”), one of the most conventionally mellifluous poems that Wordsworth ever wrote, is cast in much the same mold as is “Goody Blake and Harry Gill”:

Glide gently, thus forever glide,

O Thames! that other bards may see,

As lovely visions by thy side

As now, fair river! come to me.

O glide, fair stream! for ever so;

Thy quiet soul on all bestowing,

Till all our minds for ever flow,

As thy deep waters now are flowing.

(“Lines,” ll. 17–24)18

Oh! what’s the matter? what’s the matter?

What is’t that ails young Harry Gill?

That evermore his teeth they chatter,

Chatter, chatter, chatter still.

Of waistcoats Harry has no lack,

Good duffle grey, and flannel fine;

He has a blanket on his back,

And coats enough to smother nine.

(“Goody Blake and Harry Gill,” ll. 1–8)

The contrast provides a particularly good example of the kind of range that is characteristic of Wordsworth’s versification. The only structural difference between the two stanzas is the placement of the augmented rhymes. Otherwise, Wordsworth relies entirely on diction, placement of pause, and punctuation to create, in “Lines,” a poem in which the individual sounds and rhythms of the speaker’s words are entirely and significantly fitted to the meter and, in “Goody Blake and Harry Gill,” one in which every stylistic device seems calculated to underline the habits of mind that make the speaker’s diction and syntax radically unfit for conventional metrical presentation.

In “Lines” a speaker, obviously a poet (he speaks of “other bards”), surviews his position in the stream of time and literary history with a comprehensiveness of mind appropriate to the place, time, and subject (he not only remembers Collins but does so on the spot where Collins remembered Thomson).19 Like the initial speaker of “The Sailor’s Mother,” his harmonious patterning of vocal sounds functions emblematically as well as expressively: the absence of tension between metrical pattern and realization functions almost as an element of characterization. He has mastered a number of conventional poetic techniques that indicate his right to call himself a “bard.”

In “Goody Blake and Harry Gill,” a speaker who is more like the speaker of “The Thorn” than of “Lines,” at least in his credulity, does almost as much “chattering” as his subject’s teeth. The frequency of such obvious concessions to meter as repetition (especially of his protagonist’s names), cliché fillers (“it must be said,” “as you may think”), and awkwardly colloquial contractions (“is’t”) helps to create a sense of this speaker as a village minstrel or balladeer with very different sensibilities from Thomson, Collins, and the young poet of “Lines.” In fact, in a few places it is difficult to read metrically without wrenching normal pronunciations in a manner associated with doggerel. How, for example, ought the second line of the following to be pronounced?:

The description above the line shows the problem: the ambiguity in relative stress in the first three syllables allows at least three realizations. Both 1 and 2 would be acceptable in most four-beat verse. The natural tendency to subordinate an adjective to the noun it modifies, however, tends to make number 1 a bit strained (it hints at a rare and disruptive triple offbeat), particularly given the kind of insistent ground rhythm that is apparent throughout the poem.20 Number 2 is objectionable for the same reasons; it would be perfectly acceptable in more conversational, less robustly rhythmic, verse. In this context, however, it may seem too subtle, given the metrical set. This leaves the hyper-regular realization of number 3, which requires the line to be read exactly in the way that teachers of expressive and subtle pronunciation in poetry, from Gascoigne through Thelwall to the present day, eschew:

This is not to say that the third reading is the “correct” reading, but only that such a reading is possible (and even hinted at) given the rules of this meter, tendencies in the language, and the metrical set. In any sensitive reading it will vie with the less singsong possibilities as an element of the line’s inherent optionality. Perhaps the best way to think about the tensions inherent in such a line is as an element in the presentation of a comic counterpart and contrast to the tensionless lines of the “bard” in “Written upon the Thames.” The wide range of possibility in the realization of the line exposes, very much as do rhymes that hint at mispronunciation (July/truly), the medium of the poem and makes the telling inherently comic at the speaker’s expense.

Such characteristics, along with the insistently paratactic syntax of the poem, define the speaker of “Goody Blake and Harry Gill” as a character whose mind, whatever its virtues, lacks the ability to “see the whole of what he is about to convey” except in a very schematic way.

There is no subtle, organically uninsistent subordination of parts to the whole here:

And fiercely by the arm he took her,

And by the arm he held her fast,

And fiercely by the arm he shook her,

And cried, “l”ve caught you then at last!”

(ll. 89–92)

Wordsworth’s acknowledgment in the Preface of the “blind association” of pleasure that a reader is wont to feel in reading poems written in the same or similar meter suggests that such widely various use of the same meter within a collection of poems is yet another way in which Wordsworth employs his principle of similitude in dissimilitude. The relationship between this poem and “Lines,” like the relationship between the two speakers of “The Sailor’s Mother” or between slow speech and rapid meter in “The Thorn,” finally may work to encourage active comparison between those minds represented as aspiring to, and often achieving, imaginative “surviews” and those represented as variously focused on objects and events normally overlooked by the mind thus engaged. Such are the rhythms of the mind itself and of the society of which the individual forms a part.

These examples of Wordsworth’s practical application of his theory of metrical opposition reveal a strong tendency toward metrical experimentation that would seem important to understand. This is particularly the case in light of evidence that these experiments spring from a specifically Wordsworthian motive that remains unaccounted for in the largely Coleridgean tradition of metrical analysis that has tended to dominate discussion of romantic versification. Wordsworth’s metrical particularities and peculiarities are as deeply rooted in his own ideas concerning similitude in dissimilitude as Coleridge’s are in his specifically organic theories. Proper understanding of the role that meter plays in Wordsworth’s attempt to explore relationships among a wide range of types of mind—and among a variety of tendencies in the individual mind—will require a reexamination of the ways in which a use of metrical form is judged to be successful. It would be as useless as it is obviously wrong to judge the use of meter in the second half of “The Sailor’s Mother” according to the same standards we use for the speaker of “Lines,” especially when Wordsworth provides so many clues to the reader that his definition of successful metrical experimentation goes far beyond the desire merely to make his verse sound conventionally harmonious or mellifluous. That Wordsworth can, and does, use the same stanza form for conventionally harmonious and unconventionally cacophonous effects in the same collection of poems—and even within individual poems—suggests that his understanding of pleasure as the product of the active perception of similarity in dissimilarity is a chief force, in theory and in practice, behind his variety of metrical styles.

In “The Concept of Meter: An Exercise in Abstraction,” Wimsatt and Beardsley state that “it is just as important to observe what meter a poem is written in (especially if it is written in one of the precise meters of the syllable-stress [accentual-syllabic] tradition) as it is to observe what language the poem is written in.”21 The view of Wordsworth’s metrical theory advanced in the first part of this study suggests that this statement is particularly applicable to Wordsworth’s poetry. Wordsworth’s distinction between the law of received metrical patterns (“the passion of metre,” “the letter of metre,” “the law of long and short syllable”) and the actual embodiment of vocal sounds in temporal succession (“the passion of the subject,” “the passion of the sense,” “the spirit of versification”) is presented in the critical prose not to recommend the entire subordination either of letter to spirit or spirit to letter but to call his reader’s attention to the nature and extent of the powers exerted by each in the process of writing and reading poems.

The “complex end” of a poem, Wordsworth argues, always involves to some degree an active interchange between creative power and the conventional embodiments of power. The metrical frame, in this view, is an indispensable element contributing to the expressive ends of the poet; in addition, it frequently functions, through its complex relationship with the diction and syntax of the poem, not merely as a vehicle but as a trope. The process of bringing individual expression into relationship with conventional metrical patterns may be regarded both as analogous to and as an actual instance of the action and reaction, flux and reflux, of the mind and all forms of power within which and against which it acts. It follows, then, that an adequate perception of and response to the creative power exercised in any given poem must include a solid understanding of the nature of the power exerted by metrical convention in that poem. Reading Wordsworth metrically demands a Wordsworthian respect for the power that the metrical frame exerts, not in default of, but in conjunction with, powers of mind.