Notes

INTRODUCTION

1. Letter of 17 December 1836 from Barron Field to Wordsworth, quoted in Ernest De Selincourt, ed., The Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth, The Later Years, Part III, 1835–1839, 2d ed., rev. Alan G. Hill (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982), 355 n. 4 (hereafter cited as LY 3).

2. Stephen Gill, William Wordsworth: A Life (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), 312–13. Field’s copy of Wordsworth’s Poems (1815), which records in minute detail Wordsworth’s revisions in subsequent editions of the Poetical Works, is held at the Wordsworth Library, Grasmere. See also Barron Field’s Memoirs of Wordsworth, ed. Geoffrey Little (Sydney: Australian Academy of the Humanities, 1975). Little’s notes include Wordsworth’s annotations to Field’s MS. Letter of 17 December 1836 from Field to Wordsworth, quoted in LY 3:355 n. 4.

3. Rhyme’s Reason: A Guide to English Verse, enl. ed. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1989), 1.

4. See The Pedlar, MS M, ll. 100ff. (MS copied about 6–18 March 1804): “Oh! many are the Poets that are sown / By nature, men endued with highest gifts, / The vision and the faculty divine, / Yet wanting the accomplishment of verse” (James Butler, ed., The Ruined Cottage and The Pedlar [Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1979], 391). The lines eventually form the basis of The Excursion, Book First, ll. 77ff. Many of Wordsworth’s comments about poetry and poetic craft touch upon this distinction between a natural or “silent” poet and the poet who is also an artist in verse, capable of organizing language in enduring forms. Wordsworth discusses the product of such organization as instances of “sensuous incarnation” of poetic power, in the “Essay Supplementary to the Preface” of 1815 (The Prose Works of William Wordsworth, ed. W. J. B. Owen and J. W. Smyser [Oxford, 1974], 3:65) (hereafter cited as Prose). See, for example, The Fourteen-Book Prelude, ed. W. J. B. Owen (Ithaca, N.Y., 1985), 13.264–74 (hereafter cited as 14-Bk Prelude)—in The Thirteen-Book Prelude, ed. Mark L. Reed (Ithaca, N.Y., 1991), 12.264–74 (hereafter cited as 13-Bk Prelude)—and Wordsworth’s tribute to his brother John, the silent poet, in “When to the Attractions of the Busy World,” in The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth, ed. Ernest de Selincourt and Helen Darbishire (Oxford, 1940–49), 2:118–23 (hereafter cited as PW). Jonathan Wordsworth discusses the complexities of the silent poet and Wordsworth’s figurative discussion of poetic incarnation in “As with the Silence of the Thought,” in High Romantic Argument: Essays for M. H. Abrams, ed. Lawrence Lipking (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1981), 41–76. See also Stephen K. Land, “The Silent Poet: An Aspect of Wordsworth’s Semantic Theory,” University of Toronto Quarterly 42 (1973): 157–69.

5. Chief among these exceptions are listed below. Some of these works focus on an aspect of Wordsworth’s metrical theory or practice in the midst of treatments of a broader range of topics. Some of them are more specialized treatments of a particular element of the topic under consideration in this study. I wish here to acknowledge my indebtedness to these works: On Wordsworth’s theoretical position and its relation to the history of English prosodic thought, W. J. B. Owen, Wordsworth as Critic (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969); Judith Page, “Wordsworth and the Psychology of Meter,” Papers on Language and Literature 21 (1985): 275–94; Donald Wesling, The New Poetries (Lewisburg, Pa.: Bucknell University Press, 1985); and Dennis Taylor, Hardy’s Metres and Victorian Prosody (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988). On the Lyrical Ballads, Stephen Parrish, The Art of the “Lyrical Ballads” (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973); Mary Jacobus, Tradition and Experiment in Wordsworth’s “Lyrical Ballads” (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976); John E. Jordan, Why the “Lyrical Ballads”? (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1976); and Don Bialostosky, Making Tales: The Poetics of Wordsworth’s Narrative Experiments (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984). On Wordsworth’s stylistic development, Paul Sheats, The Making of Wordsworth’s Poetry, 1785–1798 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973). On the blank verse, Christopher Ricks, “A Pure Organic Pleasure from the Lines,” Essays in Criticism 21 (1971): 1–32; Marina Tarlinskaja, English Verse: Theory and History (The Hague: Mouton, 1976); Lee M. Johnson, Wordsworth’s Metaphysical Verse: Geometry, Nature, and Form (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982). On the sonnets, Lee M. Johnson, Wordsworth and the Sonnet. Anglistica, vol. 19. (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1973). On various aspects of Wordsworth’s musicality in relation to English poetic traditions, John Hollander, especially in Images of Voice: Music and Sound in Romantic Poetry, Churchill College Overseas Fellowship Lectures, No. 5. (Cambridge: W. Heffer and Sons, 1970); Vision and Resonance: Two Senses of Poetic Form (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975); and Melodious Guile (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1989). My study, Numerous Verse: A Guide to the Stanzas and Metrical Structures of Words worth’s Poetry, Studies in Philology, Texts and Studies Series (86, iv) (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989), provides a comprehensive descriptive catalogue of Wordsworth’s verse forms.

6. John Hollander pointed out as early as 1970 the difficulty of apprehending the metrical forms of English romanticism through the eyes and ears of its “devouring offspring, Modernism.” See Hollander’s “Romantic Verse Form and the Metrical Contract,” in Romanticism and Consciousness, ed. Harold Bloom, 181–200 (New York: Norton, 1970). Recent examples of continued interest in the topic are Timothy Steele, Missing Measures: Modern Poetry and the Revolt against Meter (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990) and David Perkins, “How the Romantics Recited Poetry,” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 31 (1991): 655–71. Perkins’s article, which appeared after the arguments pursued here were long developing, gives an overview of work that promises eventually to cover several of the topics that I claim here are insufficiently treated in romantic criticism. Perkins’s conclusions—that the romantic period is a period of “transition” in attitudes concerning verse recitation, that “Romantic recitation was far more musical than we now conceive” (665), and that criticism of the romantic period may well benefit from closer attention to the sources and effects of this “sensuously appealing” art than has been paid in recent years—are all consonant with the arguments and aims of this study.

7. Perkins, “How the Romantics Recited Poetry,” 655.

8. For a recent discussion of the influence of such developments on dramatic performances of Shakespeare’s blank verse (and for an informative attempt to supply a means for distinguishing Shakespeare’s metrical aesthetic from our own), see George T. Wright, Shakespeare’s Metrical Art (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1988).

9. See Robert Alter, The Pleasures of Reading in an Ideological Age (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989), esp. 23–48 and M. H. Abrams, “How to Do Things with Texts,” in Doing Things with Texts, ed. Michael Fisher, esp. 293–96 (New York: Norton, 1989) for discussions of the losses in subtlety and “literary tact” that can and frequently do result from the theoretical collapsing of literary and nonliterary language into the single category “discourse.”

10. Coleridge’s remarks on Wordsworth’s stylistic “inconstancy,” in Biographia Literaria; or, Biographical Sketches of My Literary Life and Opinions, ed. James Engell and W. Jackson Bate (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1983), 2:121–26 (hereafter cited as BL), are echoed throughout the tradition of commentary on Wordsworth as artist. See, for example, Matthew Arnold’s 1879 preface to the Poems of Wordsworth: “In [Wordsworth’s] seven volumes the pieces of high merit are mingled with a mass of pieces very inferior to them; so inferior to them that it seems wonderful how the same poet should have produced both” (The Complete Prose Works of Matthew Arnold, ed. R. H. Super [Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1973], 9:42). Such attitudes are obviously behind Saintsbury’s claim that Wordsworth’s corpus is distinguished by “amazing inequality” of style, an inequality that Saintsbury traces directly to the “uncertainty of his prosodic grip.” See A History of English Prosody (London: Macmillan, 1906–10), 3:71.

11. Evidence concerning Wordsworth’s memorization of verse is conveniently summarized in W. K. Thomas and Warren U. Ober, A Mind For Ever Voyaging: Wordsworth at Work Portraying Newton and Science (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1989), esp. 14–16. For extended discussions of the poetic use to which Wordsworth’s put his prodigious memory, see (in addition to Thomas and Ober) Edwin Stein, Wordsworth’s Art of Allusion (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1988).

12. On the issue of metrical “framing,” see chapters 1 and 2, and Hollander, “Romantic Verse Form”: “Romantic metrical theory, as informal a body of thought as it is, finally avows the emblematic, framing, defining role of metrical format as consistently as does that of Whitman, Hopkins, or some of the poets of our own day” (200).

13. See my Numerous Verse, “Introduction” and the Catalogue, passim.

14. William Hazlitt, “Lectures on the English Poets, VIII: On the Living Poets,” in The Complete Works of William Hazlitt, ed. P. P. Howe (London: Dutton, 1930–34), 5:162. Evidence of the survival of this assessment of romantic prosody may be found in Carl Woodring, Politics in English Romantic Poetry (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970). Although Woodring says he finds it “personally hard to assert that the French Revolution exerted pressure for a renovation in prosody,” he goes on to assert that “a new freedom entered English prosody with the romantic generation, a freedom that brought relaxation, if not revolution, as in the free substitution of trisyllabic feet within a basic iambic meter. The new freedom cracked the regular prosody of the Popian couplet, broke open the Bastille of the closed couplet itself, gave new life to stanzaic forms that had not been exercised for a century, and created … a great variety of new stanzaic forms” (11).

15. On the prevalence (and deleterious effects) of a progressive, developmental model in historical discussions of metrical styles, see Paul Fussell, Theory of Prosody in Eighteenth-Century England, Connecticut College Monograph No. 5,1954, esp. 161–63. “Next to a natural ear able to distinguish the rhythm of a waltz from that of a march,” says Fussell, “a healthy suspicion of the validity of the idea of progress in the arts seems to me to be the metrical historian’s and theorist’s most useful stock in trade” (161). Fussell calls for a “re-alliance” of prosodic study with “the sense of history” (163).

16. See, for example, Alicia Ostriker, Vision and Verse in William Blake (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965) in which romantic prosodic styles are divided cleanly into “liberal” and “conservative.” According to Ostriker, Blake’s genuinely liberal originality provides the exception to the rule that “liberal practice in versification limped far behind liberal theory” (24) until at least as late as the composition of Christabel (30).

17. Among recent attempts to reassess and to challenge the applicability of Coleridgean categories to Wordsworth’s verse, I have found Don Bialostosky’s adaptation of M. M. Bakhtin’s dialogic theories particularly congenial in a general way. In Bialostosky’s recognition of an important dimension of pleasurable play of voice in Wordsworth, and in his emphasis upon the poem as an entity that is capable of resisting under the proper circumstances a stifling univocal effect, I find support (and, in some instances, a context) for my own specifically metrical and historically oriented approach. See Bialostosky’s Making Tales and Wordsworth, Dialogics, and the Practice of Criticism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

18. Bysshe’s The Art of English Poetry (London, 1702, 1705, 1708, with many reprintings thereafter) has been called “very likely the most influential prosodic handbook ever written” (Brogan 242). A. Dwight Culler, “Edward Bysshe and the Poet’s Handbook,” PMLA 63 (1948): 858-85, provides a detailed treatment of Bysshe’s influence, as does the same author’s introduction to the Augustan Reprint Society edition (No. 40) of the first part of Bysshe’s work, The Art of English Poetry (1708; Los Angeles: William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, 1953). Wordsworth owned a copy of the 1710 issue of Bysshe’s book. See Chester L. Shaver and Alice C. Shaver, Wordsworth’s Library: A Catalogue Including a List of Books Housed by Wordsworth for Coleridge from c. 1810 to c. 1830 (New York: Garland, 1979), 44.

19. For Johnson’s comments, see his “Life of Pope,” in Lives of the English Poets, ed. George Birkbeck Hill (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1905), 3:251. For the fullest recent discussion of Augustan “period style” and its implications for romantic prosody, see Wesling, New Poetries, esp. 29–85. This topic will be taken up in detail in chapter 3.

20. See Wordsworth’s letter to Charles Henry Parry: “People’s ears have however lately become accustomed to that freer movement, which I am not so likely to be reconciled to, as a younger Reader” (LY 4:89–90). See also Mary Moorman, William Wordsworth: A Biography. The Later Years, 1803–1850 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), 572 n. 1.

21. William Hazlitt, “My First Acquaintance with Poets,” in Complete Works 17:118–19.

22. On the difficulties of re-creating a “period style,” and on the multiplicity of styles exhibited in the “transitional” romantic period itself, see Perkins, “How the Romantics Recited Poetry.”

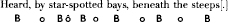

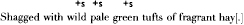

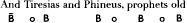

23. Attridge’s system, in giving appropriate attention both to a normative pattern of expectation (or “metrical set”) and the actual physical content of verses, is designed to steer between “the Scylla and Charybdis” that destroy many prosodic arguments: that is, it resists both “identifying metre with the actual physical characteristics of particular utterances (a rock against which musical scansion and instrumental measurements run the risk of being dashed),” and the “danger of abstracting metrical structure too far from the spoken language (a whirlpool which generative metrics finds it hard to avoid).” The system instead relies upon the “fundamental nature of language rhythm itself: a sequence of controlled variations in the release of energy, experienced both physiologically and psychologically, which underlies all our speech activities.” Derek Attridge, The Rhythms of English Poetry (London: Longman, 1982), 312.

24. “Stress” and “nonstress” (or “unstress”) are used here and throughout the study as relative terms; that is, they distinguish the prominence of individual syllables in a sequence in relation to other syllables in a sequence. The use of “stress” implies no distinction among the various elements contributive to this articulatory or acoustic prominence. For the purposes of this study, a “stress” may result from relative prominence of pitch, duration, loudness, or any combination of the three. The word does not imply, as it does for some commentators, loudness or intensity alone. “Syllable” is employed throughout the study to mean “the smallest rhythmic unit of the language.” Debates about the precise phonetic nature of the syllable are for the purposes of metrical scansion largely beside the point. See Attridge, Rhythms of English Poetry, 60–67.

25. Attridge’s “base rules” allow an offbeat to be realized by one or two unstressed syllables (161). The issue of whether or not Wordsworth’s verse allows two-syllable offbeats in any other circumstances than as part of an “initial inversion” or an “implied offbeat” formation, is taken up in detail in chapters 1, 3, and 5.

26. The rules in this section are summarized from “The Rules of English Metre,” chapter 7 of Attridge, Rhythms of English Poetry, 158–213.

27. References are to book and line.

28. Studies in Philology 84 (1987): 365–93.

1. SIMILITUDE IN DISSIMILITUDE

1. References to the Preface to Lyrical Ballads (hereafter cited as LB) are, unless otherwise noted, to the text of 1850 as it appears in W. J. B. Owen and J. W. Smyser, eds., The Prose Works of William Wordsworth (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974). The 1850 text has been chosen because it includes Wordsworth’s 1802 additions, many of which focus upon metrical issues.

2. See Prose 1:184 for analogues to Wordsworth’s statement in eighteenth-century aesthetics. Owen and Smyser point in particular to parallels in Francis Hutcheson, Inquiry into the Original of our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue (London, 1726), Adam Smith, “Of the Nature of that Imitation which takes place in the Imitative Arts,” in The Works of Adam Smith (London, 1811), Sir Joshua Reynolds (Discourse 11), Joseph Priestley (Oratory), and James Beattie, Essays on Poetry and Music (London, 1779). See also Coleridge’s discussion of imitation (as opposed to copying) as dependent upon the “interfusion of the SAME throughout the radically DIFFERENT, or of the different throughout a base radically the same” (BL 2:72).

3. On the “passion of the subject” (Ernest De Selincourt, ed., The Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth, The Early Years, 1787–1805, rev. Chester L. Shaver, 434 [hereafter cited as EY]), see the discussion of Wordsworth’s letter of 1804 to Thelwall, below.

4. For a recent discussion of the importance of such “overdetermined” language in literary art see Robert Alter, The Pleasures of Reading in an Ideological Age (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989), esp. 82–83.

5. Although Thelwall’s “Introductory Essay” (from which I quote here) apparently was not published until 1812, parts of the Selections for the Illustration of a Course of Instructions on the Rhythmus and Utterance of the English Language (London, 1812) were in circulation, as course materials, well before this date, and Thelwall may be presumed to have been elaborating the ideas in the “Introduction” during the time of his correspondence with Wordsworth. See Thomas Stewart Omond, English Metrists: Being a Sketch of English Prosodical Criticism from Elizabethan Times to the Present Day (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1921), 125–28.

6. For a representative discussion of Wordsworth’s metrical theory as based on a view of meter as superficially ornamental, see Owen, Wordsworth as Critic, 125–27. For an example of the survival of this assumption, see Ernst Häublein, who calls Wordsworth’s attitudes “superficial” and “unorganic” (The Stanza [London: Methuen, 1978], 6).

7. The letter was not published until 1967, which helps to explain why it has not received the critical attention it deserves. Other than my own citation of the letter in Numerous Verse (6), I am aware of only two published uses of the quotation: Perkins, “How the Romantics Recited Poetry” (658, 663) and Stephen Gill, William Wordsworth: The Prelude, Landmarks of World Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 29–30. Perkins uses Wordsworth’s comments in the course of an argument, much broader in scope than is mine, concerning differences in performance of verse in the romantic period and in the twentieth century. Gill cites the passage in his very useful short discussion of the verse of The Prelude (chapter 2). He emphasizes (following Ricks, “Wordsworth: ‘A Pure Organic Pleasure from the Lines’”) the constant interplay and tension in Wordsworth’s blank verse between syntactic structures and “the properties of printed verse, which are perceptible only to the eye.”

8. The general tendencies, if not the complex specifics, of this development in romantic prosodic theory and practice toward greater expressive loosening of metrical rule are summarized by Omond, English Metrists; Saintsbury, History of English Prosody; Fussell, Theory of Prosody; Ostriker, Vision and Verse, and Taylor, Hardy’s Metres. Tarlinskaja, English Verse, provides the statistical analysis to support this assessment of tendencies.

9. The quotation copied in DC MS 14 is from Richard Payne Knight, “The Progress of Civil Society” (1796). See Duncan Wu, Wordsworth’s Reading 1770–1799 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 81–82. Wu provides a text of the note, from which the following excerpt is drawn: “Dr. Johnson observed, that in blank verse, the language suffered more distortion to keep it out of prose than any inconvenience to be apprehended from the shackles & circumspection of rhyme …. This kind of distortion is the worst fault that poetry can have; for if once the natural order & connection of the words is broken, & the idiom of the language violated, the lines appear manufactured, & lose all that character of enthusiasm & inspiration, without which they become cold & vapid, how sublime soever the ideas & the images may be which they express” (Wu, 82).

10. For the importance of subordination of meter to grammar in the development out of the romantics of modern metrical styles, see Wesling, New Poetries, chaps. 1 and 2.

11. Taylor wishes to argue in Hardy’s Metres that Wordsworth and other romantics failed to understand meter as abstraction—as a law in dialectic interplay with the variety of speech rhythm—but erred on the side of “variety for its own sake” because of their revulsion from the too-strict and mechanical metrical “law” of their immediate predecessors (15–17). It remained for the Victorians, specifically Coventry Patmore and Hardy, to grasp fully the implications of meter as abstraction. As the present discussion suggests, I do not agree with Taylor’s assessment of Wordsworth’s prosodic sense (which Taylor acknowledges sometimes approaches the goal attained by the Victorians) as merely “impressionistic” (17). Wordsworth’s discussion of “the passion of meter” (overlooked by Taylor) is nothing if not an acknowledgment of dynamic interplay between contrary systems of organization. In a separate article, “Hardy and Wordsworth,” Victorian Poetry 24 (1986): 441–54 Taylor notes that Hardy developed a key assumption concerning the “mimetic” function of meter that he found in Wordsworth; that is, that “through meter and rhythm the poem can model the interaction of mind and world” (451).

12. Wordsworth’s use of “long” and “short” is, of course, imprecise (see comments on “stress” and “unstress” in the Introduction, above). It is also entirely characteristic of the period, and is to be expected from a poet whose primary training in prosodic terminology would have come through study of classical, chiefly Latin, verse, in which duration is of chief prosodic importance. Wordsworth’s use is consistent throughout his life (see, for example, the prose “Advertizement” to The White Doe of Rylstone and LY 2:30). The usage, however, implies no tendency actually to regard difference in duration alone as the salient feature of English verbal rhythm. (Wordsworth does not consider himself to be writing in quantitative meters.) “Stressed” and “unstressed” may be substituted for “long” and “short” in Wordsworth’s descriptions without misrepresenting his theoretical position.

13. For the importance of Thelwall, see Omond, English Metrists, 115, 125–28. As T. V. F. Brogan, English Versification, 1570–1980, 223, points out, most if not all of what is important to or representative of prosodic trends in Thelwall’s work is anticipated by Joshua Steele, in Prosodia Rationalis (London, 1779). But see Omond’s discussion of a possible line of influence from Steele through Thelwall to Coleridge’s Christabel meter.

14. See the quotation on Thelwall’s title page, from Shaftesbury: “Milton and Shakespeare have restored the antient Poetick Liberty, and happily broken the Ice for those who are to follow them; who, treading in their Footsteps, may, at leisure, polish our Language, lead our Ear to finer Pleasure, and find out the true Rhythmus, and harmonious Numbers, which alone can satisfy a just Judgment, and Music-like Apprehension.”

15. See Edwin Guest, A History of English Rhythms (1838; reprint, London, 1882). Guest cites Thelwall as a purveyor of the “fashionable opinion” that elidable syllables in earlier verse “may be pronounced without injury to the rhythm.” The extent to which Thelwall (and other “fashionable” romantic prosodists) are willing to go in scanning even Dryden and Pope with variable numbers of syllables per line is, for Guest, extreme. As will be shown below, it would also have been so for Wordsworth, although Guest includes Wordsworth and Coleridge both among those who have “countenanced this error” (175–76).

16. Here I speak of course not of the specifics of Thelwall’s system, but of the general issue of its treatment of syllables. Other, more directly influential, romantic commentators and practitioners justify variable syllable counts on other grounds. Southey, for example, advocated free “substitution” of trisyllabic feet in disyllabic measures through analogy with a classical model (any “iambic” foot may be filled with an “anapest”). See Southey’s letter to Wynn, 9 April 1799, in Selections from the Letters of Robert Southey, ed. J. W. Warter (London, 1856), 1:69. Coleridge, of course, developed one of the most influential accentual alternatives to syllable-counting verse in Christabel, in which “accents” alone determine the metrical form of the line, and in which the total number of syllables per line may vary freely from four to twelve. On the importance of the treatment of syllables in reading older English verse, see Edward R. Weismiller, “Metrical Treatment of Syllables,” in The Princeton Handbook of Poetic Terms (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1986), 145–46 and Wright, Shakespeare’s Metrical Art, esp. 151 –54. Wright calls the issues involved in the performance or omission of extrametrical syllables “notoriously treacherous” (151).

17. See Steele, Missing Measures, 55–68.

18. See Note on Scansions and Prosodic Terminology in the Introduction for the use of “marriage” as descriptive of the interaction of meter and rhythm. Borrowed form Attridge, the term is of course particularly apt for a discussion of Wordsworth, who so frequently describes the interaction of mind and nature as a figurative “marriage.”

19. For a discussion of meter and other schemes as potential tropes, see Hollander, Melodious Guile.

20. On the issue of metrical form as symbolic of the ideal or the metaphysical in Wordsworth’s verse, informing and countering the “natural,” see Lee M. Johnson’s treatment of large-scale “geometrical” patterns in Wordsworth’s verse (Wordsworth’s Metaphysical Verse). Geometrically based metrical patterns, like geometry, provide “a mathematical ordering of the external universe—a union of abstraction and concreteness that, in a way poetically parallel to Newton’s, is not restricted to one individual’s subjectivity but possesses a logic which may be tested and shared by others” (51). The extent to which I am in agreement with many of Johnson’s arguments (particularly those asserting the seriousness of Wordsworth’s commitment to metrical art) will be sufficiently obvious. My objections to his arguments center chiefly on how this interpenetration of ideal form and particularized concrete instance is experienced in the act of reading. Whereas Johnson requires a reader to recognize geometrical proportions (the “golden section,” for example) underlying some extended passages of blank verse, I argue that the tensions between metaphysical and physical, ideal and real, abstract and concrete, external and internal, are pervasively manifested in the actual physical texture of the verse, insofar as it continually strikes the reader or listener as simultaneously governed by number and rule and open to seemingly infinite free play and variation. Johnson does touch upon these topics in his chapter 4, “The Art of Conceptual Form.”

21. See, for example, Ted Hughes’s comments on the subject: “I think it’s true that formal patterning of the actual movement of verse somehow includes a mathematical and a musically deeper world than free verse can easily hope to enter. It’s a mystery why it should be so” (See Häublein, Stanza, 11–12).

22. Hazlitt, “My First Acquaintance with Poets,” 118–19.

23. See Fussell, Theory of Prosody, esp. 53ff, 97.

24. William Cockin, The Art of Delivering Written Language (London, 1775), 135.

25. Joseph Addison, The Spectator, no. 285 (26 January 1712), in The Spectator, ed. Donald F. Bond (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965), 3:13. For other arguments and analogies justifying the power of meter to improve language, see Fussell, Theory of Prosody, esp. 53ff., 97.

26. John Dryden, “Essay of Dramatic Poesy,” in The Essays of John Dryden, ed. W. P. Ker (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1926), 1:107.

27. Edward Manwaring [Mainwaring] Stichology (London, 1737), 74.

28. See Wordsworth’s comments on “manufactured” verse in the Alfoxden notebook, quoted above (note 9).

29. For parallel comments on the operation of linguistic trickery in prose (specifically in the prose of Godwin and others who attempt to “lay down rules for the actions of Men”), see Wordsworth’s fragmentary “Essay on Morals” (Prose 1:103–4).

30. See Coleridge, Lectures 1808–1809: On Literature, ed. R. A. Foakes (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1987), 1:494–95; Emerson, “The Poet,” in The Collected Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983), 3:6–7.

31. The main lines of the standard critical dichotomy between these two schools of thought are conveniently summarized by Fussell (Theory of Prosody) and by Wesling (New Poetries, esp. 34). It is important to keep in mind that these attitudes were becoming increasingly polarized during the years when Wordsworth was beginning to publish: “To the conservatives [Augustan prosodists], the process [of the making of a poetic line] was genuinely one of construction, of fitting existing materials into a preconceived plan; to the liberals [romantic period prosodists and their predecessors], the process was one of organic “creation,” in which the plan gradually evolved as the created work took shape” (Fussell, Theory of Prosody, 48).

32. The comment appears in J. Payne Collier’s preface to Coleridge’s Seven Lectures on Shakespeare and Milton (London, 1856), Iii.

33. For comments on this poem as a locus classicus of organic metrical theory, see Fussell, Theory of Prosody, 48 n. 43 and “Some Observations on Wordsworth’s ‘A Poet!—He hath put his heart to school,’” Philological Quarterly 37 (1958): 454–64.

34. It has perhaps not been sufficiently noted by Wordsworthians that Wordsworth’s call for the language of real life is one in a long history of attempts to redress perceived imbalances between the language of discourse and the language of art. As Barbara Herrnstein Smith puts it in reference to these periodic movements, poetic revolutions are always fought over the issue of the relationship between the dictates of art and of natural discourse; it is only in critical discourse that the two strands in this relationship are held as separable. See Poetic Closure (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968), 30 and n. 23.

35. Tom Moore, Tom Moore’s Diary, ed. J. B. Priestley (Cambridge, 1925), 185. In this passage Moore also reports that Wordsworth spoke of “the immense time it took him to write even the shortest copy of verses,—sometimes whole weeks employed in shaping two or three lines, before he can satisfy himself with their structure.”

36. Wordsworth later reuses the substance of these comments in a letter to Sir William Maynard Gomm (16 April 1834), in which he makes explicit the connection between his dedication to his craft and the distinction made in The Excursion (book 1, ll. 77ff), between the Poet and “Poets that are sown / By Nature” yet “[want] the accomplishment of verse” (LY 2:704).

37. In speaking of diction chiefly as the product of passion, I am of course speaking in relative, not absolute, terms. In fact, Wordsworth’s theory of the relationship between diction and expression is based on the same kind of paradoxical unity of competing aspects as underlies his metrical theory. See Land, “Silent Poet.”

38. Preface to Poems, 1815; Prose 3:26-27.

39. Hollander, Vision and Resonance, 136.

40. For an example of this critical assumption, see Ann Williams, Prophetic Strain (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 166–67. Williams argues that Wordsworth attempts to create in “fictive discourse” an “illusion” of “natural discourse” (the terms are Barbara Herrnstein Smith’s, in On the Margins of Discourse). This “interest in appearing to dissolve the margins of discourse,” says Williams, “may also throw light on Wordsworth’s insistence that poetry uses ‘the language really spoken by men’” and may “illuminate his somewhat inept discussion of the function of meter.” See also James C. McKusick, Coleridge’s Philosophy of Language, Yale Studies in English, 195 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1986), where Wordsworth’s discussion of meter in the Preface to LB is characterized as an attempt to “extricate” himself from the “embarrassment” posed by “the evident artifice of poetic meter” to his theory and practice of “natural” poetry (113).

41. Evidence of Wordsworth’s interest in, and respect for, the power of bad poetry to please surfaces frequently, and reinforces my contention that a main concern of his metrical art is to explore the ways in which poems work to oppose (but not to overpower) the “bigotry” of unanalyzed and passive taste. See, for example, the “Appendix” to the Preface to LB: “It would not be uninteresting to point out the causes of the pleasure given by extravagant and absurd diction … ” (Prose 1:162). Henry Crabb Robinson reports that Wordsworth spoke to him in March 1808 of his intention to write an essay on the pleasure produced by bad poetry. Wordsworth was still interested in this topic as late as September 1808, when he remarked that either Coleridge or he himself would write the essay (Mark L. Reed, Wordsworth: The Chronology of the Middle Years, 1800–1815 [Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1975], 378, 395) (hereafter cited as CMY).

2. METRICAL TENSION AND VARIETIES OF VOICE

1. Although most treatments of the disagreements between Coleridge and Wordsworth on this score have tended to assert the shortcomings of Wordsworth’s thought, Wordsworth’s differences with Coleridge have been treated sympathetically (though with emphases and conclusions different from those of this book) by Parrish, Art of the Lyrical Ballads (esp. 14–24), Johnson, Wordsworth’s Metaphysical Verse (esp. 188–91), Bialostosky, Making Tales (esp. 51–54), and Page, “Wordsworth and the Psychology of Meter.”

2. A letter to Sotheby of July 1802 in which Coleridge complains of this difference of opinion with Wordsworth, suggests that the issue was a fundamental and long-standing source of disagreement between the two poets: “Metre itself implies a passion, i.e. a state of excitement, both in the Poet’s mind, & is expected in the Reader—and tho’ I stated this to Wordsworth, & he has in some sort stated it in his preface, yet he has [not] done justice to it, nor has he in my opinion sufficiently answered it.” Collected Letters of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. Earl Leslie Griggs (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1956–71), 2:812 (hereafter cited as STCL).

3. For evidence that Wordsworth in many cases heightened in revision effects that Coleridge had singled out in Biographia Literaria as “disharmonious,” see Eric C. Walker, “Biographia Literaria and Wordsworth’s Revisions,” Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900 28 (1988): 569–88. See also Walker’s “Wordsworth’s ‘Haunted Tree’ and ‘Yew-Trees’ Criticism,” Philological Quarterly 67 (1988): 63–82, which argues in part that “much of the energy of Wordsworth’s poetry is often generated in the exchange” between different levels of style and language (79).

4. For an analysis pertinent to these concerns, arguing that Wordsworth’s poetry seeks to embody a range of expressive peaks and valleys even at its most admittedly autobiographical, see Mark L. Reed, “The Speaker of The Prelude,” in Bicentenary Wordsworth Studies in Memory of John Alban Finch, ed. Jonathan Wordsworth (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1970), 276–93.

5. John Jones, The Egotistical Sublime: A History of Wordsworth’s Imagination (London: Chatto and Windus, 1954), 84–85. On “the structure of distinct but related things that is the world of Wordsworth,” see 33ff.: “[Wordsworth] is not in revolt against the Great Machine, the master-image of eighteenth-century science and philosophy. Only the phrase is un-wordsworthian. … he would prefer something more supple, like ‘this universal frame of things.’His complaint is that nobody has as yet observed its component parts with sufficiently devoted care, or experienced fully the power and beauty of its movement.”

6. Ll. 19–24; quotations from “The Sailor’s Mother” are from the 1807 text as it appears in Jared Curtis, ed., Poems, in Two Volumes and Other Poems, 1800–1807 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1983), 77–78.

7. For the influence of Prior’s “Ode,” see Earl R. Wasserman, Elizabethan Poetry in the Eighteenth Century, Illinois Studies in Language and Literature, 32 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1947), 104–6.

8. The title of Gray’s ode on first publication in Dodsley’s was “Hymn to Adversity.” Mason restored Gray’s MS title, “Ode … ” in 1775. Wordsworth refers to the poem as an “Ode” in the I.F. note to “Ode to Duty.” (Curtis, Poems, in Two Volumes, 407.)

9. Quotations from Coleridge’s poems, as well as dates of composition, are from The Complete Poetical Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. E. H. Coleridge (London: Oxford University Press, 1912) (hereafter cited as STCPW). The dates of composition of the two poems in question here are presented by the editor as conjectural.

10. Several recent treatments of “The Sailor’s Mother” have dealt fruitfully with the issue of its stylistic contrasts. In “Wordsworth’s Dialogic Art” (1989), Bialostosky makes the poem a test case for understanding Wordsworth’s thoroughgoing commitment to a “dialogic” poetics, based upon complex interplay of voices. He also discusses the poem in Making Tales (136–38) and in Wordsworth, Dialogics, and the Practice of Criticism (67–73). See also Gene W. Ruoff, “Wordsworth on Language: Toward a Radical Poetics for English Romanticism,” Wordsworth Circle 3 (1972): 204–11. Though none of these treatments centers on specifically metrical issues, each tends to support my arguments concerning Wordsworth’s keen interest in complex and theoretically unlimited kinds of metrical “intertexture.”

11. For definitions of “initial inversion condition” and other metrical terms used in this chapter, see Note on Scansions and Prosodic Terminology in the Introduction.

12. See the note on “Descriptions of Stanza Forms” for “consonance rhyme” and “promoted rhyme” (as well as for “augmented rhyme,” used below).

13. Wordsworth’s revision of this line for PW (1827) suggests that part of the awkward effect may have been unintended: “From bodings, as might be, that hung upon his mind.” Nevertheless, while the revision introduces, in the word “hung,” an element of imaginative diction lacking in the first version (picking up and extending the implications of the “burden”), it does so, I think, without homogenizing the rhythmic and metrical texture of the poem (the double pause remains). See the “Preface” to Poems (1815), for Wordsworth on the imaginative power of the verb “to hang” (Prose 3:31).

14. Coleridge is speaking here (chapter 17) without specific reference to “The Sailor’s Mother”: “For facts are valuable to a wise man, chiefly as they lead to the discovery of the indwelling law, which is the true being of things, the sole solution of their modes of existence, and in the knowledge of which consists our dignity and our power.”

15. On distinctions of “kind” and of “degree” compare Preface to LB: “Among the qualities … enumerated as principally conducing to form a Poet, is implied nothing differing in kind from other men, but only in degree” (Prose 1:142).

16. “Tail rhyme” refers to a class of stanzas distinguished by their use of rhyming lines (or “tails”), interposed between two or more pedes (usually couplets or triplets). Variations on the most common form of tail rhyme (aa4b3cc4b3), the “romance six” used in many medieval metrical romances, play an important role in Wordsworth’s stanzas. PW (1849–50) contains twenty-seven poems in tail-rhyme stanzas and an additional twenty poems in stanzas (such as that used in “The Thorn”) that incorporate modified tail-rhyme sections. See my Numerous Verse, 57–60 and Appendix II.

17. Wordsworth’s stanza differs from Gray’s chiefly in its use of an additional line and of unrhymed lines (three of eleven lines in each stanza have no rhyme). Both stanzas, however, are built up from the same basic stanza forms (ballad stanza and tail-rhyme), a practice uncommon before Gray. Wordsworth uses a stanza identical to Gray’s (a4b3a4b3ccdee4d3) in “The Oak and the Broom” and “The Waterfall and the Eglantine” (both 1800). A closely related stanza (abb4a3ccdee4d3) is employed in “Elegiac Verses, in Memory of My Brother, John Wordsworth” (1805; pub. 1842).

18. “Lines Written near Richmond …” (1798) was divided in LB (1800) into two poems: “Lines Written While Sailing in a Boat at Evening” and “Lines Written near Richmond upon the Thames” (“Remembrance of Collins”). The stanza quoted is the third stanza of the 1798 poem; it became the first stanza of “Lines … Richmond” in 1800. The texts cited here and in the quotations from “Goody Blake and Harry Gill” are the 1798 Reading Texts in James Butler and Karen Green, eds. Lyrical Ballads, and Other Poems, 1797–1800 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1992), 104–5, 59–62.

19. Wordsworth’s title makes obvious reference to Collins’s “Ode on the Death of Mr. Thomson,” which when published carried this announcement: “The scene of the following STANZAS is suppos’d to lie on the Thames near Richmond.” Wordsworth’s stanza, ababcd_cd_4, bears an obvious relation to the form used by Collins in his “Ode” (abab4). Wordsworth alludes directly to Collins’s “Ode” in ll. 29–40 and note.

20. On the “stress hierarchies,” which enforce (among other things) the rhythmic subordination of adjectives to nouns, see Attridge, Rhythms of English Poetry, 67-70.

21. William Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley, “The Concept of Meter: An Exercise in Abstraction,” in The Structure of Verse: Modern Essays on Prosody, ed. Harvey Gross, 168 (New York: Ecco Press, 1979).

3. “WORDS IN TUNEFUL ORDER”:

WORDSWORTH’S EARLY VERSIFICATION, AN EVENING WALK AND DESCRIPTIVE SKETCHES

1. References are to book and line.

2. Commentators have variously identified the poems and poets to which Wordsworth here refers. DeQuincey identified Gray and Goldsmith as among the favorites that Wordsworth and John Fleming “chaunted” for two hours at a time while strolling around Esthwaite. Havens and others have assumed that the passage refers to Dryden and Pope, but the kind of poetry described here—“airy fancies / More bright than madness or the dreams of wine” (11.591–92)—makes this unlikely (see Raymond Dexter Havens, The Mind of a Poet [Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1941], 401–2). The editors of the Norton Prelude suggest Macpherson’s Ossian translations, based on Wordsworth’s imitation and echoing of these in the Vale of Esthwaite, but the references to “verses” in l. 589 suggests otherwise, as Macpherson’s work is written in rhythmic prose. (Jonathan Wordsworth et al., eds., The Prelude 1799, 1805, 1850 [New York: Norton, 1979], 182 n. 1.)

3. Compare Coleridge on such susceptibilities as necessary to a great poet (he is discussing Shakespeare’s early verse): “The delight in richness and sweetness of sound, even to a faulty excess … I regard as a highly favorable promise in the compositions of a young man. ‘The man that hath not music in his soul’ can indeed never be a genuine poet.” He goes on to say that incidents, thought, interesting feeling and the “art of their combination or intertexture in the form of a poem” may be learned by a man of talent: “But the sense of musical delight, with the power of producing it, is a gift of imagination …. It is in [this] that ‘Poeta nascitur non fit’” (BL 2:20).

4. Emile Legouis’s catalogue and discussion of the stylistic peculiarities of EW and DS is still enormously helpful. His list of some twenty characteristics includes archaisms (“broke” for “broken”); intransitive verbs used transitively (“I gaze / the ever-varying charms,” EW, ll. 17–18); irregular suppression of the article; “violent suppression of an auxiliary” (“They not the trip of harmless milkmaid feel,” EW, l. 226); suppression of the verb; use of words in an obsolete sense; Miltonic inversions of subject and verb (“Starts at the simplest sight th’unbidden tear,” EW, l. 44); imitation of Latin ablative absolute; “inversion of the direct pronominal object, with all the characteristics of one of Milton’s Latin constructions.” Emile Legouis, The Early Life of William Wordsworth, trans. J. W. Matthews (New York: Dutton, 1932), 134–35.

5. For the fullest recent discussion of the “period style” of the Age of Pope, and its implications for romantic prosody, see Wesling, New Poetries, esp. 29–85.

6. Topographical Poetry in XVIII-Century England (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 1936), 297–391.

7. For a survey of these issues, see William Bowman Piper, The Heroic Couplet (Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University Press, 1969).

8. Johnson’s comments appear in his “Life of Pope” (Lives of the English Poets 3:251).

9. Ostriker identifies the “great cage” in which Har and his captived birds sing in Tiriel (plate 3, ll. 10–25) as Blake’s description of Augustan verse (Vision and Verse, 21). In the “Public Address,” Blake condemns Pope for his “Metaphysical Jargon of Rhyming,” a failure of execution that is among “the Most nauseous of all affectation & foppery.” In the same work, Dryden’s rhymes are acknowledged to be preferred by “Stupidity” over Milton’s verse because of their “Monotonous Sing Song Sing Song from beginning to end” (Poetry and Prose, 565, 570).

10. DS, ll. 680–85. All quotations from the 1793 text of the poem are from the Cornell University Press edition, ed. Eric Birdsall (1984).

11. The revision of “reading it long” to “changing the accent” is a good example of the imprecision in (and interchangeability of) prosodic terminology mentioned above (chapter 1, note 12).

12. Averill’s description of the poems as “portraits of the young poet’s mind” is apt. I am in disagreement, however, with his elaboration of the significance of the portraits as “emblems of a dead self that is the object at once of condescension and of nostalgia” (EW, 16). I find Wordsworth’s attitudes much more inclusive of this earlier self than the terms “condescension” and “nostalgia” would suggest. As has been argued in chapters 1 and 2, Wordsworth would not, I think, make as clean a distinction as would Averill (or Coleridge) between what Averill calls “intrinsic” poetic merit and the merit of a poem as an index of a particular kind of insufficiency of perception and expression, presented for the purpose of comparison with other (and perhaps more comprehensive and steadily focused) kinds of mental activity. See James Averill, ed., An Evening Walk (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1984).

13. For Wordsworth’s broad definition of “workmanship,” see his letter to Maria Jane Jewsbury, 4 May 1825 (LY 1:343); for his listing the precise operation of the “logical faculty” among the signs of workmanship, see his letter to W. R. Hamilton, 24 September 1827 (LY 1:545–46).

14. For Wordsworth’s reputation as a writer of verse among the boys at Hawkshead, see the query, variously reported, of the older schoolfellow whom James A. Butler has called the “first Wordsworthian”: “I say, Bill, when thoo writes verse dost thoo invoke t’Muse.” (Butler, “The Muse at Hawkshead: Early Criticism of Wordsworth’s Poetry,” Wordsworth Circle 20 [1989]: 140.) Another version of the incident quotes the older boy thus: “How is it, Bill, thee doest write such good verses? Doest thee invoke Muses?” (See Reed, CEY, 291).

15. Christopher Wordsworth, Memoirs of William Wordsworth (London, 1851), 1:10. For a discussion of Wordworth’s diction in relation to Pope’s Dunciad, see Abbie Findlay Potts, Wordworth’s Prelude: A Study of Its Literary Form (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1953; Octagon Books, 1972), 33–38.

16. All quotations from “School Exercise” are from Dove Cottage MS 1, which differs in several instances of punctuation and capitalization from the text as it appears in PW.

17. The comma after “thence” in l. 86 in Dove Cottage MS 1 seems out of place; PW omits it.

18. See Attridge, Rhythms of English Poetry, 124. On the fundamental importance and staying power of the four-beat line in English verse, see Attridge (chapter 4) and Joseph Malof, A Manual of English Meters (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970), esp. chap. 4. In his Introduction (1830) to the Lay of the Last Minstrel, Sir Walter Scott argues that the four-stress line is “so natural to our language, that the very best of our poets have not been able to protract it into the verse properly called Heroic, without the use of epithets which are, to say the least, unnecessary.”

19. Alexander Pope, Correspondence of Alexander Pope, ed. George Sherburn (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1956), 1:23.

20. See Rambler, No. 90, in which Johnson argues that parts of a verse containing fewer than three syllables are “in danger of losing the very form of verse.” The poet, therefore, ought to restrict himself whenever possible to “only five pauses” (after syllables three through seven) in pentameter verse (2:111). Evidence that Wordsworth was conscious of these rules as rules (and was not merely operating according to the evidence of his ear) may be seen in the letter of 1816 to Robert P. Gillies—Ernest De Selincourt, ed., The Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth, The Middle Years, Part II, 1812–1820, 2:343 (hereafter cited as MY 2, followed by the page number[s]), quoted at length and discussed in chapter 5, below.

21. The percentages cited there and throughout this study are based on my own counts, unless otherwise noted. They are presented here with qualifications, because the placement of a pause, especially in unpunctuated lines, is often a matter of interpretation. As a hedge against subjectivity, I have employed a very strict method, and have defined as “unbroken” almost all lines in which the pause is not indicated by a mark of punctuation. Following this approach, I define some 60 percent of the verses in most heroic couplets (Pope’s included) as “unbroken,” even though an impassioned reading might actually require pauses in many of these unpunctuated lines. The percentages cited throughout this study are based on the number of lines containing pause, not on the total number of lines. This and subsequent tables are offered, then, not as definitive descriptions but as comparative indices of large tendencies. My indebtedness to Walter Jackson Bate for various aspects of the approach of this chapter will be obvious to anyone familiar with The Stylistic Development of Keats (New York: Modern Language Association, 1945). My counts are not comparable to his, since his tabulations assign pause to all but the most obviously unbroken lines.

22. M. L. Barstow [Greenbie] singles out this aspect of the early verse for comment: “Wordsworth was always careful to avoid hiatus – more careful than most poets of the nineteenth century, to whose ears it was less offensive than the poets of the preceding century felt it to be.” Wordsworth’s Theory of Poetic Diction (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1917), 74 n. 3.

23. Field’s text at this point quotes Hazlitt, who charges that Wordsworth unfairly slighted Dryden and Pope, “whom, because they have been supposed to have all the possible excellencies of poetry, he will allow to have none.” Wordsworth calls the charge “monstrous.” See Field’s Memoirs of Wordsworth, 37 and n. 43.

24. These most common kinds of syllabic reduction are conveniently summarized in Bysshe’s Art of English Poetry: Weismiller recommends using the blanket term “elision” for all of these techniques, while adding a number of other kinds to the list: for example, coalescence of contiguous vowels when the first is stressed (monosyllablic “prayer” and disyllabic “piety,” for example); O or U assimilated or converted to consonantal [w] before a vowel (“echoing”/ ec[w]ing; “shadowy”/ shad[w]y); blending into a single syllable a final syllabic liquid or nasal and a vowel beginning a following word (“river of”; “open his”). See Weismiller, in Preminger, Princeton Handbook, 145–46.

25. See Stuart Curran, Poetic Form and British Romanticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), esp. 29–39. Curran notes the outpouring of “sonnets of sensibility” in the 1780s (of which Wordsworth’s is one), and especially the importance of Charlotte Smith’s Elegiac Sonnets (1784). For Wordsworth’s admiration of Charlotte Smith see PW 4:403.

26. The poem was never published by Wordsworth in full; an “Extract” appears in editions, 1815 ff. See PW 1:270–83, for a text of 569 lines pieced together from three MSS.

27. Coleridge also was fond of this line. He slightly misquotes the line as it appears in EW (“Dash’d down the rough rock, lightly leaps along”) in the MS to “Songs of the Pixies”: “Dash’d o’er the rough rock, lightly leaps along,” and he seems to be recalling it in Lines to a Beautiful Spring in a Village (1794). See Averill, Evening Walk, 44.

28. Thomson, for example, tends to find the diversity of the seasons neither important in itself nor a challenge to the harmony he everywhere perceives. His poem, unlike Wordsworth’s, proceeds through continuous finding of what he set out to find: order in variety. See William Langhorne, Fable X of “Fables of Flora,” for an assessment of Thomson that emphasizes his blank verse as a vehicle for a vast intellectual vision of “truth resistless, beaming from the source / Of perfect light immortal” against which “Vainly boasts / That golden broom its sunny robe of flowers.” Langhorne contrasts this vision with the octosyllabics of William Hamilton of Bangour, in which “Whatever charms the ear or eye,” no matter how various, may be included. (Dr. Robert Anderson, ed. Works of the British Poets [London: John and Arthur Arch, 1795], 11:264–65.)

29. Because my primary concern in this chapter is limited to Wordsworth’s early published verse (especially EW and DS), because so much of the work before composition of these poems is translation (and therefore presents special problems), and because much of the very early work is not yet available in adequate scholarly editions, a full consideration of the juvenilia would be impractical here. On matters relating to style in Wordsworth’s juvenilia see Sheats, Making of Wordsworth’s Poetry. Greenbie, Wordsworth’s Theory of Poetic Diction, is informed by its author’s acute sensitivity to verse rhythm and for that reason is still most helpful. On stylistic and metrical characteristics of Wordsworth’s translations from the Latin, see the series of works on this subject by Bruce E. Graver: “Wordsworth’s Translations from Latin Poetry” (Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1984); “Wordsworth and the Language of Epic: The Translation of the Aeneid,” Studies in Philology 83 (1986): 261–85; “Wordsworth’s Georgic Beginnings,” Texas Studies in Language and Literature 33 (1991): 137–59.

30. Throughout this chapter, EW (composed probably 1788–89) and DS (composed 1791–92) are discussed as if they were contemporaneous, despite the earlier composition of the former poem. Their simultaneous publication and Wordsworth’s usual linking of them in conversations and letters suggests that the poet tended to think of the two poems as similar enough in style to be read and discussed in tandem. For Wordsworth’s “apprenticeship,” see the tongue-in-cheek reference in “The Idiot Boy”: “I to the Muses have been bound / These fourteen years, by strong indentures” (ll. 337–39).

31. Critical Review, n.s. 8 (July 1793), 347; n.s. 8 (August 1793), 472–73.

32. Compare Hugh Blair, for whom rhyme and expressive “vehemence” are at odds: “The constraint and strict regularity of rhyme, are unfavourable to the sublime, or to the highly pathetic strain. … It is best adapted to compositions of a temperate strain, where no particular vehemence is required in the Sentiments, nor great sublimity in the Style” (Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres [London, 1785] 3:110). For twentieth-century variations on the argument, with specific reference to Wordsworth’s couplet poems, see Legouis, Early Life of William Wordsworth, 128-33; Geoffrey Hartman, “Wordsworth’s Descriptive Sketches and the Growth of a Poet’s Mind,” PMLA 76 (1961): 519–27 and Wordsworth’s Poetry 1787–1814 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1964), esp. 110–15; and Frederick A. Pottle, The Idiom of Poetry (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1946), 129–30. But see also Sheats, who argues briefly that the couplet is not, at least in EW, an “aesthetic error,” but the “most obvious vehicle for a demonstration of poetic skill” (Making of Wordsworth’s Poetry, 50 and 262 n. 9).

33. EW employs two twelve-syllable, six-beat (hexameter) verses (ll. 186, 206); three hexameter lines appear in DS (ll. 105, 379, 653).

34. In his mature verse, and in revisions of EW and DS, Wordsworth tends to avoid hiatus less through typographical means and more through avoidance of phrasings that would require elision.

35. Another example appears at DS, l. 137:

36. References are to book and line.

37. The same difficulty arises in l. 3 of “Sweet was the walk along the narrow lane” (PW 1:290), a sonnet written 1789–92; published in 1889:

38. Averill, ed., An Evening Walk, 248-49. All quotations from the MSS of An Evening Walk and from the 1793 text of the poem are from this edition.

39. This is the same effect that Pope achieves with the well-known line in the Essay on Criticism, “And ten low words oft creep in one dull line.” The effect may be understood as stemming from a lack of subordination of stresses. The offbeats are all realized by words that tend to require stress. Wordsworth draws upon these means again in DS, l. 593: “To pant slow up the endless Alp of Life.”

40. See Z. S. Fink, ed. The Early Wordsworthian Milieu. A Notebook of Christopher Wordsworth with a Few Entries by William Wordsworth (New York: Oxford University Press, 1958). The passage in question, dated 1784–85 by Fink, appears on page 5 of the notebook:

41. Averill, Evening Walk, 54 and 54 n. to ll. 193–94.

42. Birdsall, Descriptive Sketches, 70 app. crit.

43. Sheats discusses the challenge of Wordsworth’s description to concordia discors theories (Making of Wordsworth’s Poetry, 61ff).

44. Blair warns about the disruptiveness of this effect: “There are some, who, in order to exalt the variety and the power of our Heroic Verse, have maintained that it admits of musical pauses, not only after those four syllables, where I assigned their place [after the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth], but after any one syllable in the Verse indifferently, where the sense directs it to be placed. This … is the same thing as to maintain that there is no pause at all belonging to the natural melody of the verse; since, according to this notion, the pause is formed entirely by the meaning, not by the Music. But this I apprehend to be contrary both to the nature of Versification, and to the experience of every good ear” (Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres 3:108–9).

45. Several of these early pauses occur in the second line of a couplet after a run-on first line and an initial inversion, and thus challenge further the structural integrity of the couplet. See, for example, Evening Walk, 305–6: “Or the swan stirs the reeds, his neck and bill / Wetting, that drip upon the water still.”

46. For the connection between speed of performance and early or late placement of pause, see the discussion of the psychological tendency to equalize the time required to read the two unequal parts of a divided line (noted above in connection with the “School Exercise”).

47. For a discussion of the pervasive influence of The Traveller on DS, see Potts, Wordsworth’s Prelude, 131–48. Potts suggests that technical problems posed by Goldsmith’s antithetical and analytic style are central to Wordsworth’s use of the poem in DS.

48. W. K. Wimsatt, Jr., The Verbal Icon (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1954), 166.

49. See Wesling, New Poetries, esp. 18–22.

50. Sheats notes the Virgilian ending (Making of Wordsworth’s Poetry, 73–74), but refers to the couplets of DS as “still-conventional.” Birdsall points out the echo of “Windsor Forest” in the Cornell edition of Descriptive Sketches, 116 n. to ll. 792–809.

51. Theresa Kelley has recently called attention to the conclusion of DS as perhaps the most unabashedly sublime passage in Wordsworth: after the 1790s, says Kelley, “Wordsworth would never again offer so unequivocal a celebration of the sublime.” See Wordsworth’s Revisionary Aesthetics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 3ff. Kelley also notes in Wordsworth’s passage an echo of Thomson’s celebration of Britannia, in The Seasons (“Summer,” 11.423–310); see p. 3 and 209 n. 5.

52. The echo is noted by Birdsall, Descriptive Sketches, 116 n.

53. For Wordsworth’s notes on this conversation, see Prose 1:91–98 and BL 2:205.

54. For “consonance rhyme” and other terms from William Harmon’s “Rhyme in English Verse: History, Structures, Functions,” Studies in Philology 84 (1987): 365–93, see Note on Scansions and Prosodic Terminology in the Introduction.

55. Darbishire, The Poet Wordsworth, 8–9; Ben Ross Schneider, Jr., Wordsworth’s Cambridge Education (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957), 41.

56. The Spenserians are in Dove Cottage MS 2, printed by De Selincourt as XVI (b) in PW 1:293–95; see Stephen Gill, ed. The Salisbury Plain Poems of William Wordsworth (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1975), 290–92.

57. Robert Anderson, “The Impatient Lassie,” in Ballads, In the Cumberland Dialect (Alnwick: W. Davison, n.d), 32.

58. When the pronunciation of “height” changed from that suggested by the survival of the “ei” in its stem [het] to modern [halt] is uncertain, and “height” does appear as a rhyme for “weight” in late-seventeenth- and early-eighteenth-century verse (see Dryden, “Epilogue to the Second Part of the Conquest of Granada,” ll. 15–16: “None of ’em, no not Jonson, in his height / Could pass, without allowing grains for weight”). The OED, however, suggests that [halt] was the most common pronunciation at least from the sixteenth century (as Milton’s spelling “highth” suggests) and all of the examples that I have been able to gather suggest that standard eighteenth-century pronunciation would have been [al], as in these couplets from Pope and Cowper:

He said, and clim’d a stranded lighter’s height

Shot to the black abyss, and plunged down-right.

(Dunciad, book 2, ll. 287–88)

Duly, as ever on the mountain’s height

The peep of morning shed a dawning light.

(“Charity,” ll. 260–61)

59. See Wordsworth’s letter of 23 May 1794 to William Mathews: “It was with great reluctance that I huddled up those two little works [EW and DS] and sent them into the world in so imperfect a state. But as I had done nothing by which to distinguish myself at the university, I thought these little things might shew that I could do something” (EY, 120).

60. Sheats comments in his discussion of Wordsworth’s Hawkshead period that Wordsworth, living in a region that attracted more than its share of descriptions, would have been sensitive from an early age to the gap between the landscape as it is known to someone who lives in it—someone whose mind and affections had been formed through active interchange with it in all its variety—and that landscape as it appeared in guides and literary descriptions. Living in the Lake District, says Sheats, would have given Wordsworth “daily instruction in the relationship between word and thing” (Making of Wordsworth’s Poetry, 22).

61. For the development of these tendencies from Alexander Baumgarten’s Philosophical Reflections on Poetry (1735) through the New Critics, see M. H. Abrams, “From Addison to Kant: Modern Aesthetics and the Exemplary Art,” in Doing Things with Texts, 159–87, esp. 173–83.

62. 13-Bk Prelude 8.69; 6.539; 10.725–26.

4. VARIETIES OF RHYME: THE STANZAIC VERSE OF THE LYRICAL BALLADS

1. Robert Mayo, “The Contemporaneity of the Lyrical Ballads,” PMLA 69 (1954): 516–17. For Saintsbury’s dismissal of Wordsworth’s verse (History of English Prosody 3:74), see the Introduction to this book.

2. See my Numerous Verse, passim and esp. 8–13.

3. Richard Payne, in “‘The Style and Spirit of the Elder Poets’: The Ancient Mariner and English Literary Tradition,” Modern Phihlogy 75 (1978): 368–84 suggests that the diction and placement of the Rime are calculated to make the issue of style itself—and particularly the function of stylistic variety—a singularly important aspect of the reader’s experience of the collection as a whole. Payne finds it “downright startling” to consider the “composite” style of the Rime (with its mingling of Chaucerian idiom, Renaissance neologism, and modern northernisms) and of LB as a whole (with its introductory poem so dissimilar stylistically from what is to follow), in relation to the similarly composite stylistic texture of Percy’s Reliques.

4. The similarities observed by Fussell (Poetic Meter, 140–41) between this stanza and a stanza appearing in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century “mad songs,” will be discussed below in connection with “The Idiot Boy.”

5. Among the several studies that emphasize Wordsworth’s representation of various kinds of speech as central to his aims in LB, I am most indebted to Parrish, Art of the Lyrical Ballads; Frances Ferguson, Wordsworth: Language as Counter-Spirit (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1977), esp. 11–34; and Bialostosky, Making Tales.

6. These ten are the Rime of the Ancient Mariner, “Foster-Mother’s Tale,” “The Female Vagrant,” “Anecdote for Fathers,” “We are Seven,” “The Last of the Flock,” “The Mad Mother,” “The Idiot Boy,” “Expostulation and Reply,” and “Old Man Travelling.”

7. For the circumstances of the composition and collection of the 1798 edition, see Mark L. Reed, “Wordsworth, Coleridge, and the ‘Plan’ of the Lyrical Ballads,” University of Toronto Quarterly 34 (1965): 238–53. Neil Fraistat provides a convenient summary of arguments for and against the integrity of the collection in The Poem and the Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 49–53.

8. See Gill, William Wordsworth (184–90), for an account of Wordsworth’s careful preparation of the 1800 volume. Gill suggests that Wordsworth was concerned with the minutest matters of arrangement and appearance; e.g., on “18 December Wordsworth was worrying about the shape of the volumes …. He insisted, too, on how Michael should be printed, that is, on the actual appearance of the type at certain points” (185).

9. Of 114 poems in the Annual Anthology for 1799, twenty three are written in blank verse. The remaining ninety-one poems employ thirty different forms.

10. As early as May 1798, Coleridge had told Joseph Cottle that the idea of separate publication of the individual poems in what was to be LB (1798), without Coleridge’s contributions, was “decisively repugnant & oppugnant” to Wordsworth, as the resulting collection would “want variety” (STCL 1:411–12). N. Stephen Bauer sees evidence of Wordsworth’s strong preference for collective presentation of his works throughout his career in the poet’s resistance to publishing in anthologies or annuals: “As he wrote more and more,” writes Bauer, “Wordsworth came to see his poems working together in two ways: first, shorter poems with similar characteristics combined to form single longer poems (something he encouraged by classifying the poems, beginning as early as the edition of 1800); and second, all the combined groups then united to create a single, gigantic Poem…. For his poems to affect the reader the way Wordsworth desired they must be read together[.]” See “Wordsworth and the Early Anthologies,” Library, 5th ser., 32 (1972): 37–45.

11. This and all quotations from the Lyrical Ballads are from Butler and Green, Lyrical Ballads, and Other Poems. Unless otherwise noted, the text cited is the Reading Text of LB (1800) or, in the case of passages appearing in 1798 and unchanged 1800, the Reading Text of LB (1798). Where the text of a poem published in 1798 has been changed in 1800, I have inserted the 1800 changes from the editors’ app. crit.

12. For “animated and impassioned recitation,” see the preface to Poems (1815), Prose 3:29.

13. Only one poem in the entire PW employs a true refrain: “The Seven Sisters,” a poem composed in 1800 and published in the Morning Post on 14 October 1800. It first appears in Wordsworth’s collected works in Poems in Two Volumes (1807). See my Numerous Verse, 95.

14. See Parrish, Art of the Lyrical Ballads, 122. For a convenient overview of sources and analogues, see Patrick Campbell, The Lyrical Ballads of Wordsworth and Coleridge: Critical Perspectives (London: Macmillan, 1991), 118.

15. For the relationship between this stanza and the stanza used by Gray in “Ode: on a Distant Prospect of Eton College” (1747), and “Ode on the Spring” (1748), see the discussion of “The Thorn” in Chapter 2.

16. Wordsworth published in 1835 a cento made up of a stanza each from Akenside and Beattie, with a transitional couplet from Thomson, saying in a note to that compilation that he “sometimes indulge[d]” in the “harmless” practice of “linking together, in his own mind, favourite passages from different authors” (PW 4:396). The second stanza of this cento takes a form (aab4c3b4c3d4e3d4e3) that would not seem out of place among Wordsworth’s original ten-line stanzas. The “Cento” suggests that the habits of mind indulged by Wordsworth in his “harmless” cento making also informed his selection and creation of his most distinctive longer stanzas. All but one of Wordsworth’s longer stanzas (ten to twenty lines) in PW are built up from recognizable smaller stanzaic units or couplets. The one exception is the sixteen-line stanza used in “On the Power of Sound” (a_3ba_bc5dcdef4e5gf4gh5h4), discussed below, in the Conclusion to this book. See my Numerous Verse, 12.

17. Malof, Manual of English Meters, esp. chap. 4; Attridge, Rhythms of English Poetry, esp. 80–96.

18. For tail rhyme, see Chapter 2, n. 16.

19. In the course of a discussion with different aims and concerns from mine, Paul Sheats provides some useful comments on Wordsworth’s stanza and on the issue of “inconstancy of style.” See “’Tis Three Feet Long and Two Feet Wide’: Wordsworth’s ‘Thorn’ and the Politics of Bathos,” Wordsworth Circle 22 (1991): 92–100.

20. For the text of Wordsworth’s note, see Butler and Green, Lyrical Ballads, and Other Poems, 791. In a letter of December 1814 to Gillies, Wordsworth criticizes the versification of Hogg’s The Haunting of Badlewe (1814) in terms that give further evidence of his relatively low opinion of ballad metrics: Hogg’s poem, says Wordsworth, is “harsh and uncouth,” and Hogg himself is “too illiterate to write in any measure or style that does not savour of balladism” (MY 2:179–80).

21. “The Force of Prayer,” first published in Poems (1815), appeared soon thereafter as part of a note to The White Doe of Rylstone, itself in part a retelling of a tale found in Percy (“The Rising in the North”). Wordsworth’s use of “The Force of Prayer” as an explanatory note to another poem imitates an antiquarian editorial convention (employed by Percy, for example), and suggests that the poem represents a self-conscious experiment with the ballad as a historical form. With regard to the issue of Wordsworth’s general unwillingness to break with traditional accentual-syllabic practice, see the prose “Advertizement” to The White Doe (DC MS 61, drafted and abandoned probably between 2 December 1807 and 3 January 1808). There, Wordsworth’s abortive attempt to explain the principles of his meter gives evidence that he was uneasy about the relatively frequent use of double offbeats (or “trisyllabic substitution”) in the poem. See Kristine Dugas, ed. The White Doe of Rylstone; or, the Fate of the Nortons (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1988), 185–203, esp. 201–2. A similar attitude toward accentual verse is apparent in the titling of a poem by Dorothy Wordsworth in PW; the poem (“Loving and Liking”; PW 2:102–3) is called “Irregular Verses” because it employs accentualist prosody (and is, therefore, irregular in comparison with the large majority of other poems in the collection).

22. But even in the case of “A Ballad,” the regular eight- and six-syllable verses suggest that Wordsworth’s balladry was filtered through a more consciously literary tradition of sentimental poetry and was not influenced directly by popular songs and tales. Wordsworth also used the stanza in some work composed probably between November 1796 and June 1797 and eventually published as part 2 of Coleridge’s unfinished poem “The Three Graves” (see Reed, CEY, 27; PW 1:308–12). All of the verses in Wordsworth’s contribution to the poem are syllabically regular; Coleridge’s parts 3 and 4, published in The Friend (No. 6, 21 September 1809) employ double offbeats, though less frequently than in the Rime.

23. Paul G. Brewster’s 1938 assessment continues to suffice for many commentators: it was in “ballad stanza form, meter, and rhyme,” says Brewster, that the ballad had its “greatest influence” on the poetry of Wordsworth (“The Influence of the Popular Ballad on Wordsworth’s Poetry,” Studies in Philology 35 [1938]: 611). Herbert Hartman misidentifies the cross-rhymed 4 × 4 stanza used in one-third of the Goslar poems as the “most characteristic stanza form of the Percy collection” (“Wordsworth’s ‘Lucy’ Poems: Notes and Marginalia,” PMLA 49 [1934]: 135). T. V. F. Brogan’s article on “Ballad Meter” in the New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1993) provides a good overview of the complexity involved in taxonomies of this stanza. See 118–20. On distinctions between the stanza aba4b3 (and abc4b3) and ballad meter, see Fussell, Poetic Meter, 138.

24. Cowper—to cite just one poet besides Wordsworth who maintained a clear distinction between the forms a4b3a4b3 and a4b3C4b3 – writes nearly thirty of his Olney Hymns and much occasional verse in the stanza a4b3a4b3; when he turns to parody of the popular ballad in “John Gilpin,” he also turns to the authentic ballad stanza, a4b3c4b3.

25. For a representative statement of this view, see Ostriker, Vision and Verse, esp. the historical overview in chaps. 1 and 2 (“The Conservative Background” and “The Liberal Background”).

26. Here and throughout this discussion, quotations from the Rime are from the LB 1798 text as it appears in Butler and Green, Lyrical Ballads, and Other Poems (Appendix IV: “Non-Wordsworthian Poems in Lyrical Ballads”).

27. On the general issue of stress timing and its effects, see Attridge, Rhythms of English Poetry, 70–74, 96–101.

28. Line 10 of the 1800 text has “here” for “hear”; a misprint (Butler and Green, Lyrical Ballads, and Other Poems, 109 app. crit).

29. Hallam Tennyson comments on the “contest,” held in May 1835: “My father and Fitzgerald … had a contest as to who could invent the weakest Wordsworthian line imaginable. Although Fitzgerald claimed this line, my father declared that he had composed it.” Alfred, Lord Tennyson: A Memoir by His Son (London: Macmillan, 1897), 1:153.

30. For another example of this kind of emblematic use of form in LB, see “Lines Written at a Small Distance.” At the precise point at which the speaker asserts an opposition between a “Our living Calendar” and the “joyless forms” of abstract measurements of time from which he and the addressee of the poem shall escape, the verse form shifts (from aba4b3 to a4b3a4b3).

31. Additional evidence concerning Wordsworth’s habitual practice of regarding line endings as “indicative of a conscious pause” is provided by Mark Reed, who notes that members of the Wordsworth family frequently omit appropriate punctuation at line endings in MSS of The Prelude. See 13-Bk Prelude 1.102–3.

32. Harmon, “Rhyme in English Verse,” 378–79.

33. See Lee M. Johnson, who calls “Lycidas” a “triumph of conceptual form” and compares its play of irregularity and regularity with Wordsworth’s Ode: Intimations of Immortality (Wordsworth’s Metaphysical Verse, 202-3). Johnson describes “Lycidas” as a sequence of variously irregular canzoni ending in a perfect ottava rima stanza “serving as a commiato of the whole.”

34. See Marina Tarlinskaja, Shakespeare’s Verse, 278; See also Bryan Crockett, “Word Boundary and Syntactic Line Segmenation in Shakespeare’s Sonnets,” Style 24 (1990): 600-610.

35. This copy, found in a set of LB (1800) at the State University of New York at Buffalo, is described and transcribed in the appendix of Brian G. Caraher’s Wordsworth’s “Slumber” and the Problematics of Reading (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991), 263-70. It is “signed and apparently dated” [“20th July 1848”] by Wordsworth:

She lived unknown, and few could

know

When Lucy ceased to be;

But She is in her grave—and oh

The difference to Me.!

Caraher makes no comment on the possible prosodic function of the underlining.

36. See Caroline Strong, “History and Relations of the Tail-Rhyme Strophe in Latin, French, and English,” PMLA 22 (1907): 371-417. Jerome Mitchell calls special attention to a medieval tradition of lyric use in “Wordsworth’s Tail-Rhyme ‘Lucy’ Poem,” Studies in Medieval Culture 4 (1974): 561-68.

37. See my Numerous Verse, 57-60.

38. Collier, Seven Lectures, li–lii.