5

“Infinitely the Most Difficult

Metre to Manage”

Characteristics of Wordsworth’s Blank Verse

“PROOFS OF SKILL ACQUIRED BY PRACTICE”

Wordsworth considered his blank verse a consummate artistic accomplishment. In letters written in his middle and late years, he is quick to admonish correspondents who tend (like many twentieth-century commentators) to confound the painstaking fashioning of a powerfully original and various voice in blank verse with artless or “natural” expression. In a letter of 1831, Wordsworth warns William Rowan Hamilton not to be tempted by the seeming naturalness of blank verse into supposing that the effect of effortlessness takes no effort. Although there is no “cant” in Milton’s claim to be “pouring easy his unpremeditated verse,” Wordsworth tells Hamilton, it is “not true to the letter, and tends to mislead. … I could point out to you 500 passages in Milton upon which labour has been bestowed, and twice 500 more to which additional labour would have been serviceable: not that I regret the absence of such labour, because no Poem contains more proofs of skill acquired by practice [than does Paradise Lost]” (LY 2:45). Blank verse, Wordsworth writes to Catharine Grace Godwin, is “infinitely the most difficult metre to manage, as is clear from so few having succeeded in it” (LY 2:58).

Wordsworth certainly bound himself to a long apprenticeship in the craft of blank verse. Before the publication of the 1800 Lyrical Ballads, which contained thirteen new blank-verse poems, Wordsworth had published only some 230 lines in the form in three poems, all in the 1798 Lyrical Ballads: “Lines left upon a Seat in a Yew-Tree,” “Old Man Travelling,” and “Tintern Abbey.” Between mid-1796, when he probably composed the fragment that Stephen Gill calls his “first significant use of blank verse” (“The road extended o’er a heath,” in DC MS 2),1 and early 1800, after which the bulk of the thirteen new poems in Lyrical Ballads (1800) were begun, however, Wordsworth had amassed in manuscript a body of blank verse more than twenty times the size of his public output. These five-thousand-plus unpublished verses encompass dramatic, narrative, philosophical, autobiographical, descriptive, and lyric genres. They include work on The Borderers, early work on The Prelude, the “Prospectus” to The Recluse, “The Ruined Cottage,” “Description of a Beggar,” “A Night-Piece,” and much more that would eventually find its way into print. By the time he published a substantial body of blank-verse poems in 1800, Wordsworth had been attending for some time and with impressive results to what he calls the “innumerable minutiae” on which “absolute success” in the art of poetry “depends” (LY 2:459).2

The few and “very simple” rules governing Wordsworth’s practice in pentameters are set forth in the 1804 letter to Thelwall. After making explicit his claim that the passion of meter makes it “Physically impossible,” even in blank verse, “to pronounce the last words or syllables of the lines with the same indifference, as the others, i.e. not to give them an intonation of one kind or an other, or to follow them with a pause, not called out for by the passion of the subject” (EY, 434), Wordsworth sets forth a “general rule” for the disposition of stresses: “1st and 2nd syllables long or short indifferently except where the Passion of the sense cries out for one in preference 3d 5th 7th 9th short etc according to the regular laws of the Iambic.”3 Finally, he offers this statement defining what he considers to be allowable variation within these rules: “I can scarcely say that I admit any limits to the dislocation of the verse, that is I know none that may not be justified by some passion or other” (EY, 434).

An additional set of remarks by Wordsworth, concerning the important issue of placement and variety of midline pauses, helps in constructing a more developed picture of Wordsworth’s practical rules with regard specifically to blank verse. In a letter of 1816 to Robert Pearce Gillies, Wordsworth provides a rule of thumb while describing his own practice: “If you write more blank verse, pray pay particular attention to your versification, especially as to the pauses on the first, second, third, eighth, and ninth syllables. These pauses should never be introduced for convenience, and not often for the sake of variety merely, but for some especial effect of harmony or emphasis” (MY 2:343). Earlier in the same letter, Wordsworth had objected to Gillies’s placement of pause in “The Visionary.” He faults in particular a passage in which the line breaks after the sixth syllable in three consecutive verses and offers the general criticism that Gillies “frequently introduce[s] pauses at the second syllable, which are always harsh, unless the sense justify them and require an especial emphasis” (MY 2:343).

The Wordsworth of 1816 might as well have been addressing the Wordsworth of 1793. It may be recalled that in the pentameter verse of An Evening Walk—and especially of Descriptive Sketches—placement of pause after the second syllable is a kind of stylistic mannerism and contributes to the sense of “harshness” that contemporary reviewers had sensed in the versification of Wordsworth’s debut poems. Wordsworth’s comments of 1816 show the poet had in his maturity come into broad agreement with the theory and practice of mainstream English tradition (most importantly with the practice of Milton) in which the pause in a five-beat line is in general restricted to the midline positions. (Wordsworth, however, extends the range of allowable normal pauses to include the seventh syllable.) As is common in Wordsworth’s comments about meter and rhythm, he stresses variety of placement within these relatively strict confines, while again suggesting that he would allow almost any departure from the general rule as long as it were justified by the need for “especial emphasis” or by some “especial effect of harmony.” As is the case with his discussion of “dislocation” in the letter to Thelwall, Wordsworth will exclude in theory no effect that may be justified in terms of the poet’s chief duties: to express passion and to give pleasure. The only practices he will exclude prescriptively are those that might give the impression of caprice or inattention, because such impressions undermine the chief function of versification—to provide a normative “set” against which expressive impulses play. In terms of the discussion of the passion of meter pursued in the first chapter, Wordsworth’s practical rules concerning the placement of pause reflect his concern that meter be manifested in the poem as a restricting presence or counterpassion, so that the passion of the sense may be made palpable through the dynamics of the relationship between the fixed form and infinitely variable realizations of that form.

According to Wordsworth’s “rules,” then, the blank-verse line is theoretically a ten-syllable unit with regularly alternating stress, a tendency toward internal structural balance, and a marked ending. This theoretical pattern (the passion of meter) exists, however, only in and through tense opposition with actual speech sounds and the passions that motivate them (the passion of the subject). This tension, the precise bounds of which Wordsworth consistently declines to define (“I can scarcely say that I admit any limits”), manifests itself chiefly in the interplay between an ideal and a real stress pattern (potentially causing “dislocation”) and in ever-shifting relationships between metrical lines and variable phrases, achieved through enjambment (over marked terminations) and placement of pause. A third source of tension also may be deduced from Wordsworth’s comments and from his practices, the tension (and sense of optionality) produced by the fact that real speech sounds seldom fulfill unambiguously the numerical requirements of the ten-syllable line. Is “power” disyllabic or monosyllabic? Is it “heaven” or “heav’n”? Wordsworth’s practice with regard to ambiguous syllables is less strict in his mature pentameters than in his juvenilia and in the couplets of An Evening Walk and Descriptive Sketches. As his definition of his “rules” suggests (and as his practice shows), however, he never abandoned his theoretical definition of the line as decasyllabic, nor did he adopt, as did many of his contemporaries and nineteenth-century successors, frequent “trisyllabic substitution” or variable offbeats as part of his metrical set. Wordsworth’s numerical definition of the line implies that apparently extrametrical syllables ought to be recognized as potentially significant occurrences, not merely as grace notes or (in Thelwall’s terms) “appogiaturae” to be resolved without tension in the normal course of the meter. Wordsworth’s lifelong practice of using the tension between the numerical idea of the line and its actual sound is an important source of the liveliness and power of his blank verse.

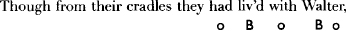

The blank verse of the 1800 Lyrical Ballads shows that Wordsworth had by the late 1790s already begun to work within and through the general rules that he lays out in 1804 and 1816. Departures from the rules of syllable number and stress placement are, appropriately, rare. Only in “The Brothers” does Wordsworth employ a significant number of genuinely hypermetrical verses (verses containing more than ten syllables that do not also contain ambiguous or elidable syllables). And there the effect is clearly intended, as it marks a generic distinction between passages of direct dramatic speech (set off by the speaker prefixes “Leonard” and “Priest”) and the narrative links between these speeches. Frequent use of unstressed “extra” final syllables (what Wordsworth calls a “trochaic ending”)4 is, of course, characteristic of dramatic blank verse and is a chief means through which such verse may be made to seem more conversational, less formal, than other kinds:

LEONARD.

These Boys—I hope

They lov’d this good old Man—

PRIEST.

But that was what we almost overlook’d,

They were such darlings of each other. For

The only kinsman near them …

(“The Brothers,” ll. 287–42)

(Note in the example also the informal effect of the ninth-syllable pause in line 240, a placement that would be avoided in Wordsworth’s nondramatic blank verse.) This kind of relatively loose blank verse is, for Wordsworth, appropriate only for passages of direct speech and occurs in his corpus regularly only in the dramatic passages of “The Brothers,” in his tragedy, The Borderers, and in some passages of quoted speech in The Excursion. When true eleven-syllable verses with unstressed endings appear elsewhere, they may be considered to serve some extraordinary expressive or emblematic end.

Dislocations of stress pattern, except for “initial inversion,” occur infrequently in the Lyrical Ballads of 1800 and are clearly related either to expressive motives or to aesthetic ends such as variety of pattern or pace. Among the most common kinds of dislocations other than initial inversion are the following (roughly in the order of their frequency of occurrence):

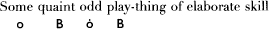

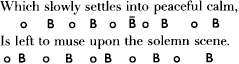

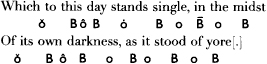

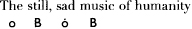

Stress-ûnal implied-offbeat pattern at the opening of a line (midline stress-ûnal patterns are much less frequent)

(“To Joanna,” ll. 48–50)

Stress-initial implied-offbeat pattern at the seventh position (or “fourth-foot inversion”—usually occurring after a strong sixth-syllable pause)

(“Lines left upon a Seat in a Yew-Tree,” ll. 37-39)

(“To Joanna,” ll. 32-33)

Stress-initial implied-offbeat pattern at the ûfth position (or “third-foot inversion”)

(“Michael,” ll. 413–15)

Because stress-initial implied-offbeat formations are rather disruptive of the metrical set, they tend not to occur earlier than the fifth position or, as Attridge puts it, “before the rhythm has had a chance to establish itself (174). Implied offbeats in the third position (or “second-foot inversion”) are indeed rare in Wordsworth’s verse (and in English verse as a whole). Marina Tarlinskaja calculates that such effects account for only 4 percent of all “inversions” in Wordsworth (English Verse, 283, table 43). More will be said about Wordsworth’s use of this source of tension below, in the discussion of “A Night-Piece.” At present, it may be sufficient to note that where it occurs, this rare kind of dislocation may be expected, like the use of eleven-syllable lines with “trochaic endings,” to mark some especially significant expressive or emblematic purpose.

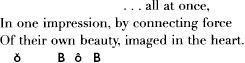

A much more common and pervasive source of metrical variety and interest is Wordsworth’s use of the less-disruptive effects of promotion or demotion of syllables. As these effects will be discussed in detail below in the course of analyses of individual passages and poems, I will limit myself here to a simple mention of one especially characteristic kind of demotion and one of promotion. Wordsworth is fond of using a relatively strongly stressed monosyllabic adjective in the third, offbeat, position. Placed in this position the syllable is felt to be in tense opposition to the meter and frequently produces a slowing effect. This probably results in large part from the strong pull in the metrical set against a third-syllable stress (for reasons mentioned immediately above):

(“Lines Written with a Slate pencil … Rydal,” l. 17)

(“There is an Eminence,—of these our hills,” ll. 7–8)

(“Tintern Abbey,” l. 92)

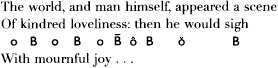

Wordsworth’s most characteristic kind of stress promotion involves the use of a normally unstressed preposition, article, or conjunction in a “beat” position. Very frequently, this promoted syllable, which has an effect opposite to the slowing effect of the demoted third syllable, falls in the sixth position. As the examples quoted above show, the effect very frequently occurs in those lines that contain a third-syllable demotion, where it seems to function as a kind of rhythmic compensation:

Such verses, in which an initial sense of slow weightiness is balanced by the diminution of stress and relative speediness of the line ending, are a Wordsworthian blank-verse trademark.

Wordsworth’s placement of pause and use of enjambment in the blank verse of Lyrical Ballads also show him to be working in accordance both with his practical rules (as these would later be set forth in the letter to Gillies) and with his ideas about the function of meter in the accomplishment of the aesthetic ends of similitude in dissimilitude. Table 2 analyzes the distribution of pause in a sample of one thousand lines from Lyrical Ballads. It allows comparison of Wordsworth’s mature practice both with his own early work in pentameters (in An Evening Walk and Descriptive Sketches) and with two very different earlier uses of the form, each of which surely influenced Wordsworth’s development—Paradise Lost and Cowper’s The Task.

TABLE 2

Distribution of Pauses after Syllables and Percentage of

Occurrence in Various Texts

| Pause | PL | ||||

| After | EW | DS | LB1 | (Book I)2 | Task3 |

| Syllable | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) |

| 1 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 1.6 |

| 2 | 15.3 | 17.9 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.3 |

| 3 | 2.9 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 7.6 |

| 4 | 18.8 | 17.5 | 13.2 | 24.2 | 23.7 |

| 5 | 8.2 | 7.4 | 13.5 | 16.6 | 11.3 |

| 6 | 15.9 | 9.5 | 16.8 | 27.0 | 21.0 |

| 7 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 12.1 | 10.7 | 12.7 |

| 8 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 4.1 |

| 9 | 0.5 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Double | 25.9 | 24.6 | 21.0 | 6.0 | 10.9 |

| Triple | 0.5 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 2.3 |

| Unbroken | 62.0 | 64.5 | 35.7 | 31.3 | 36.8 |

Note: Percentages are based upon the number of lines that employ pause; the percentage of unbroken lines relative to the total number of lines is given at the end of the table. |

|||||

Midline pause (after fourth, fifth, or sixth syllable): EW, 42.9%; DS, 34.3%; LB 43.5%; PL, 67.8%; Task, 56%; Pause after fourth, fifth, sixth, or seventh: EW, 48 3%;DS, 35.7%;LB, 55.6%; PL, 78.5%; Task, 68.7% |

|||||

1. The thousand lines analyzed were selected at random from LB (1800). They include “Lines Left upon a Seat in a Yew Tree” (66 lines); “The Brothers,” ll. 1–164; “A Narrow Girdle of Rough Stones and Crags” (86 lines); “There Was A Boy” (32 lines); “Tintern Abbey” (160 lines); “The Old Cumberland Beggar,” ll. 1–154; “Nutting” (55 lines); “Written with a Slate Pencil upon a Stone … upon One of the Islands at Rydal” (35 lines); “There is an Eminence,—or these our hills” (17 lines); “To Joanna” (85 lines); “Michael,” 11.1–146. |

|||||

2. Paradise Lost sample (book 1) consists of 798 lines. The raw numbers for each position are as follows: after 1st = 1; 2d = 27; 3d = 25; 4th = 133; 5th = 91; 6th = 148; 7th = 59; 8th = 27; 9th = 3; double = 33; triple = 1; unbroken = 250. |

|||||

3. The Task sample (book 1) consists of 770 lines. The raw numbers for each position are as follows: after 1st = 8; 2d = 21; 3d = 37; 4th = 115; 5th = 55; 6th = 102; 7th = 62; 8th = 20; 9th = 2; double = 53; triple = 11; unbroken = 284. |

|||||

Pentameter couplets and blank verse, of course, have their own structures of organization, and it may be misleading to compare them here. But the table will help to show the extent to which Wordsworth’s five-beat line becomes a different kind of rhythmic structure in the years between 1793 and 1797–1800. Whereas in 1793 Wordsworth seems to have been striving through idiosyncratic placement of pause to distinguish the movement of his verse from that of predecessors and contemporaries, by the later 1790s he has accepted midline pause as an internal structural requirement of the five-beat form. Whatever will be distinctive about his verse will emerge within the context of certain enduring rhythmic patterns, inherent in the physical form of the verse itself (its tendency to break into a balanced 4/6, 5/5, or 6/4 structure), and sanctioned by earlier use.

Similarities in the placement of pause in Wordsworth, Cowper, and Milton suggest one of the reasons why the form is “infinitely the most difficult metre to manage.” Blank verse may free the poet from the bondage of rhyming, but it imposes its own, more subtle, kinds of restraint at other levels of organization. There simply are not very many options for breaking a five-beat line without threatening its integrity as a line. At the same time, table 2 reveals some of the ways in which Wordsworth’s verse in Lyrical Ballads does in fact distinguish itself rhythmically from the other samples: multiple pauses occur more frequently than is common in the nondramatic blank-verse tradition (this accounts for the relatively low percentages in each position under Lyrical Ballads compared with both Milton and Cowper); pauses are distributed fairly equally among the midline positions (that is, Wordsworth shows no clear preference, as do Milton and Cowper, for pauses after stressed syllables over pauses after unstressed syllables); and pauses fall almost as frequently after the seventh syllable as they do in the more conventionally acceptable positions, the fourth, fifth, and sixth syllables. Milton, although showing a similar tendency to eschew pauses after the second, third, eighth, and ninth syllables, definitely favors the fourth-and especially the sixth-syllable pause (he uses these two almost twice as frequently as he does the fifth- and seventh-syllable pause), and he uses the seventh-syllable pause less frequently than does Wordsworth. Cowper, whose blank verse is commonly cited as a forerunner of Wordsworth’s because of its less Miltonically magisterial and more conversational movement, also shows a decided preference for pauses after even-numbered syllables. Cowper’s preference for the fourth-syllable pause is perhaps a residual effect of his extensive early work in couplets (fourth-syllable pause being a trademark of eighteenth-century couplet verse). It also helps to account for the relative (and appropriate) lightness and rapidity of Cowper’s line when compared with Milton’s.

Another chief source of formal tension and variety in any blank verse is, of course, enjambment, which creates potentially meaningful kinds of interplay between syntactic structures and the metrical frame. Wordsworth’s letter to Thelwall calls particular attention to line endings, as it asserts that the passion of meter is felt especially at line boundaries. At line ends, Wordsworth says, a minute sense of physical restraint must be felt, whether or not it is consonant with the rhythmic and syntactic manifestation of the passion of the subject. That is, a run-on line in good poetry does not invalidate the force of line endings; rather, it uses that inescapable force to effect.

Wordsworth uses run-on lines considerably less frequently than Milton but considerably more frequently than Cowper: 51.1 percent of the lines in the sample from Lyrical Ballads are enjambed, compared with 66.8 percent in Paradise Lost (book 1) and 36.6 percent in The Task (book 1).5 Related to the issue of frequency of enjambment is Wordsworth’s practice in the use of medial full stops (defined here as a midline pause, normally at the end of an independent clause and usually marked by punctuation stronger than a comma). Here, too, the three samples show important similarities and dissimilarities. In Lyrical Ballads, 14.1 percent (141/1000) of the lines surveyed contain a medial full stop, compared with 18 percent in the Paradise Lost sample (145/798) and 12 percent in the first book of The Task (93/770).

More revealing still is the ratio of medial full stops to all full stops. In Wordsworth’s blank verse, 15.5 percent of the lines have full stops at line endings. Milton uses line-ending full stops in only 12 percent of his verses. In Cowper—again perhaps because of habits instilled through his writing of couplets—full stops correspond with line endings in 27.1 percent of the lines. The percentages of medial full stops relative to all full stops in the three samples, then, are 47.6 percent in Lyrical Ballads, 55 percent in Paradise Lost, and only 30.7 percent in The Task. Once again, Wordsworth’s practice places him between the extremes of Milton’s heavily enjambed style—in which the paragraph, not the line or the sentence, is the chief structural unit—and Cowper’s more restrained style, in which the integrity of the line itself tends more often than not to be preserved.

These figures might easily be taken to suggest that the basic structure of Wordsworth’s blank verse is a kind of compromise between the Miltonic and Cowperian, favoring the Miltonic. And such a conclusion would not be entirely wrong by way of a general description of Wordsworth’s practice. Wordsworth does achieve greater interplay between metrical frame and syntax, line and phrase, than does Cowper. At the same time, he allows the counterpassion of the frame to manifest itself (through greater end-stopping and conformity of phrase and line) more frequently than does Milton. And Wordsworth does distribute the pause more equably among the midline positions than does either Milton or Cowper. A closer look at the Lyrical Ballads sample, however, reveals an important way in which Wordsworth’s practice is not adequately described as a compromise between seventeenth-century and eighteenth-century habits. In both Milton and Cowper, the tendencies of the larger sample provide, by and large, an accurate reflection of individual passages within the sample: that is, Milton’s clear preference for late pause and frequent enjambment and Cowper’s clear preference for early pause and infrequent enjambment tend to be in evidence throughout the samples. In the selection from the Lyrical Ballads, however, the tendency toward moderation suggested by the figures turns out to be a statistical fiction, an average of a very wide variety that does not accurately describe any one part of the sample. Any given passage of Wordsworth’s blank verse may be as frequently end-stopped and line-conscious as Cowper, as frequently enjambed and paragraphed as Milton, or virtually anywhere in between. It all depends on the expressive and aesthetic ends of the poet, on who is represented as speaking, about what, in what genre, to whom, and under what circumstances.

Distribution of Pauses after Syllables and Percentage of

Occurrence in Various Texts

| Pause After Syllable |

Tintern (%) |

Abbey | Michael (%) |

(ll. 1-146) | LB (%) |

Total |

| 1 | - | - | 2.3 | (2) | 2.7 | (17) |

| 2 | 0.4 | (5) | 2.3 | (2) | 5.0 | (32) |

| 3 | 0.5 | (6) | 4.5 | (4) | 6.0 | (38) |

| 4 | 15.9 | (18) | 7.9 | (7) | 13.9 | (88) |

| 5 | 19.5 | (22) | 12.5 | (11) | 13.7 | (87) |

| 6 | 9.7 | (11) | 23.8 | (21) | 17.3 | (110) |

| 7 | 16.8 | (19) | 6.8 | (6) | 12.4 | (79) |

| 8 | 0.4 | (5) | 5.7 | (5) | 3.8 | (24) |

| 9 | - | - | - | - | 0.4 | (2) |

| Double | 21.2 | (24) | 32.9 | (29) | 22.1 | (140) |

| Triple | 0.3 | (3) | 1.1 | (1) | 2.7 | (17) |

| Unbroken | 29.4 | (47) | 39.7 | (58) | 36.6 | (366) |

| Enjambed | 55.6 | (89) | 44.9 | (67) | 51.1 | (511) |

Note: Numbers in parentheses give the total number of occurrences of pause in each position. |

||||||

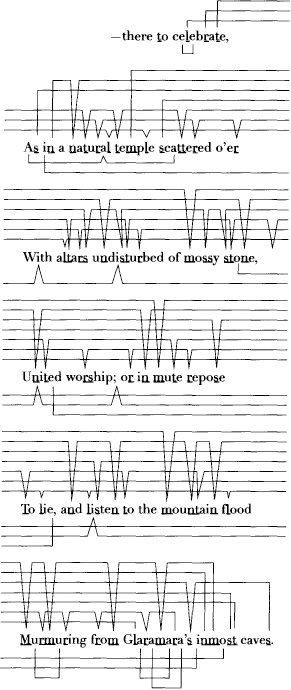

Table 3 allows comparison of Wordsworth’s enjambment and placement of pause in two parts of the one-thousand-line sample—“Michael” and “Tintern Abbey”—with the total for the entire sample.

Different kinds of poems apparently require very different kinds of verse. In the narrative poem “Michael,” Wordsworth’s blank verse is characterized by unbroken lines (39.7 percent is an extremely high percentage),6 by a clear preference for pauses after stressed syllables (especially after the sixth), and by relatively infrequent enjambment. The very high frequency of unbroken and syntactically self-contained lines contributes substantially to the effect of simplicity in “Michael”:

He had not pass’d his days in singleness.

He had a Wife, a comely Matron, old

Though younger than himself full twenty years.

She was a woman of a stirring life

Whose heart was in her house …

(ll. 80-84)

Here and throughout the poem, syntactical and metrical structures tend to be commensurate much more frequently than in Wordsworth’s blank verse as a whole. As a result, there is relatively little complexity in the interplay of the passion of the meter and the passion of the sense.

In “Michael,” the clear preference for one placement of pause (and that one late in the line) also helps to create, through the appearance of a relatively easy fit between passion and metrical scheme, a simplicity of expression appropriate to the story of a man who does not “wear fine clothes” (letter to Charles James Fox; EY, 315). The sixth-syllable pause tends to make a five-beat line appear to move slowly. And the frequent use of a single pause tends to make the pause itself seem an element of structure, as opposed to an element of expression:

Nor should I have made mention of this Dell

But for one object which you might pass by,

Might see and notice not. Beside the brook

There is a straggling Heap of unhewn stones;

And to that place a Story appertains,

Which, though it be ungarnish’d with events,

Is not unfit, I deem, for the fire-side

Or for the summer shade. It was the first,

The earliest of these Tales …

(ll. 14–22)

Note in particular how both of the midline full stops in the passage occur in the sixth position (nine of the fourteen midline full stops in the sample passage fall in this position also). In such verse, the favored midline position comes to be felt as only slightly less an element of structure than is the length of line. The placement of pause, that is, is properly an element of the “general rule” governing the verse, rather than a disruptive exception. It produces not expressive tension but a sense of pleasing variety appropriate to a narrative founded on deep, not volatile, feeling and presented for the delight of a “few natural hearts” and for the sake of those “youthful Poets” who will be the narrator’s “second self” when he is gone. The rhetorical gesture here, as in “Hart-Leap Well,” suggests a kind of preexisting bond among poet, tale, and reader. The rhythmic characteristics of the verse may be regarded as a chief means for incorporating this bond into the tale. Wordsworth offers few surprises in “Michael,” few twists and turns of passion or expression. The rhythm of his verse functions not so much as an overt challenge to preexisting habits of association but as a gentle reinforcement of salutary combinations of thought and feeling that the speaker assumes are at his disposal. This is the voice of the village storyteller, telling to effect a tale that instantiates commonly acknowledged kinds of power; it is not the voice of the bard creating new combinations of thought and feeling.

“Tintern Abbey” departs from the averages of the sample almost as sharply as does “Michael,” but in very different, even idiosyncratic, ways. Whereas “Michael” restricts the distribution of pause, “Tintern Abbey” disperses it evenly and widely in positions four to seven. Whereas the line is broken in “Michael” much less frequently than in the sample as a whole, in “Tintern Abbey” it is broken much more frequently. “Tintern Abbey” employs enjambment in 4.5 percent more of its lines than does the sample; “Michael” in 6.2 percent fewer. Such devices in “Tintern Abbey” are as appropriate to the expressive ends of a poem, the versification of which Wordsworth called “impassioned music” (PW 2:517), as is the verse of “Michael” to a “history / Homely and rude” (ll. 34–35). Pause is not, in the following passage, chiefly a structural source of pleasant variety. It is an expressive index of the tension inherent in the act of a mind engaged in complex processes of thought and feeling:

We see into the life of things.

If this

Be but a vain belief, yet, oh! how oft,

In darkness, and amid the many shapes

Of joyless day-light; when the fretful stir

Unprofitable, and the fever of the world,

Have hung upon the beatings of my heart,

How oft, in spirit, have I turned to thee

O sylvan Wye! Thou wanderer through the woods,

How often has my spirit turned to thee!

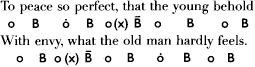

(ll. 50-58)

The paragraph break falling after the eighth syllable, the triple pause in the second full verse, and the double pause (including a second-syllable pause) in the seventh line quoted all help to create the impression of a mind engaged in a process of discovering and making—the meanings it articulates, rather than of a speaker reciting a tale the general course of which is known in advance. Phrases are allowed to take their own shape, expressing and emblematizing through tension between metrical and syntactic structures the fluxes and refluxes of the speaker’s mind.

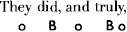

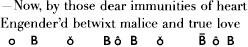

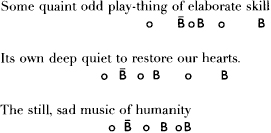

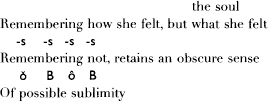

Such features of the verse call attention to the minutiae of expression to a greater degree than is usual, or welcome, in narrative verse. Note, for example, the parallel repetition, with significant syntactic and rhythmic variation, in the seventh and ninth lines of the quoted passage:

The rhythmic effectiveness of the minute change in phrase may easily be felt merely by repeating the lines, in either form, without the variation:

How oft, in spirit, have I turned to thee

O sylvan Wye! Thou wanderer through the woods,

How oft, in spirit, have I turned to thee!

How often has my spirit turned to thee

O sylvan Wye! Thou wanderer through the woods,

How often has my spirit turned to thee!

Even more revelatory of the power of Wordsworth’s repetition is the unsatisfactory effect resulting from a reversal of the repeated lines:

How often has my spirit turned to thee

O sylvan Wye! Thou wanderer through the woods,

How oft, in spirit, have I turned to thee!

The unsettling nature of this rewritten version probably results from the expectation that endings, even verse paragraph endings, will resolve tensions, not introduce them. In Wordsworth’s original version, the final line is indeed a more neatly satisfying, less complex realization of the scheme than is the first. Even the reduction of stress on the auxiliary verb (“has”) contributes. Whereas the pause in the first line allows “have” to take a full stress, in the final line the absence of a pause gives the line four primary stresses. The result is a faster paced verse that also takes advantage of the deep-seated physical pull of the four-beat, binary rhythm around which all five-beat verse plays. Its approximation of the feel of a four-beat verse contributes to its ability to function as a grounding, stabilizing influence on the paragraph as a whole.7 Such effects help to underscore and embody the speaker’s assertions, to give physical proof that the progressive regeneration of power he professes to feel is in fact under way. Rhythmic strength expresses and emblematizes the poet’s sense of regeneration upon his return to the sources of his power.

Of interest, also, is the way in which the lines call attention, through their similarity, to the very subtle but philosophically central difference between the content of the two phrases; namely, the question of the extent to which the reinvigoration of the speaker’s power, celebrated in the poem, is a result of the self-motivated “turning” (and returning) of the “I” and the extent to which it is a result of an influence other than and perhaps superior to the “I.” In short, has the speaker himself turned, or has he been turned? By repeating the phrase in rhythmically similar and dissimilar forms—one that expresses, in a broken line, the speaker’s assertion of power (I have turned), the other that acknowledges, in a single unbroken line, the primacy of the “spirit” in the act of restoration (my spirit has turned)—Wordsworth embodies in an essentially lyric mode what might be called the motivating (and paradoxical) tension underlying the entire poem. An assertion of a free and spirited, self-motivated turn out of the course that necessity seems to have dictated and an assertion of the speaker’s belief that finally it was not in fact a free and self-motivated turn are matched, rhetorically and rhythmically, not as antithetical statements but as two variations on the same theme. In such places, the passion of the sense and the passion of meter overlap and interpenetrate in complex ways. Such interpenetration tends to focus attention on the medium itself, justifying Wordsworth’s assertion that the poem might have been called an ode chiefly on the strength of its “impassioned music.”8

Another telling—and effective—difference between the blank verse of “Michael” and that of “Tintern Abbey” is evident in the use of midline full stops. In the “Michael” sample, only fourteen full stops fall in midline positions, compared with thirty-three at line ends (14/47;or 29.8 percent); “Tintern Abbey” contains twenty-seven medial full stops, and only fourteen full stops at line ends (27/41; or 65.8 percent). The difference in Wordsworth’s practice in the two poems—and especially the differences between each poem individually and the Lyrical Ballads sample totals—are a fair index of just how various Wordsworth’s rhythmic practice can be. In the total one-thousand-line sample, the percentage of medial full stops relative to total full stops is 47.2 percent (143/303). Wordsworth’s preference for end-line full stops in “Michael” is nearly as marked a deviation from this average as is the opposite preference for midline full stops in “Tintern Abbey.”

In “Michael,” the frequent coincidence of full stops with line endings is another of the many ways through which Wordsworth creates that sense of easy recitation of event that is the proper form of communication between his storyteller and the sympathetic audience. Where metrical and expressive structures are commensurate—where line endings mark units of thought—the poet foregoes one of the chief means at his disposal for creating complexity and tension:

UPON the Forest-side in Grasmere Vale

There dwelt a Shepherd, Michael was his name,

An old man, stout of heart, and strong of limb.

His bodily frame had been from youth to age

Of an unusual strength: his mind was keen,

Intense, and frugal, apt for all affairs,

And in his Shepherd’s calling he was prompt

And watchful more than ordinary men.

(ll. 40-47)

The effectiveness (and distinctiveness) of Wordsworth’s quite deliberate reduction of rhythmic complexity and tension may be appreciated by comparing it with the very different effects that issue from Southey’s attempts in the 1790s to create a blank-verse style appropriate to “homely and rude” tales. In Hannah, for example, a work frequently grouped on the basis of style with Wordsworth’s plainer blank-verse poems of the late 1790s,9 midline full stops account for fully 70 percent (21/30) of total full stops, and twenty-seven of the fifty-one lines in the poem are enjambed (52.9 percent). The rhythmic effect of such verse is the very opposite of the effect achieved in “Michael”:

[I]t was one,

A village girl; they told us she had borne

An eighteen months strange illness; pined away

With such slow wasting as had made the hour

Of Death most welcome—To the house of mirth

We held our way, and, with that idle talk

That passes o’er the mind and is forgot,

We wore away the hour.

(Hannah, ll. 5–12)

Southey avoids commensurability of phrase and metrical unit as surely as Wordsworth favors it. Whereas Wordsworth achieves simplicity of expression through devices that reduce tension between the metrical frame and the expression of the speaker (allowing in the process a certain latitude in diction, phrasing, and figures without violating the decorum of his tale), Southey seems intent on compensating for unremitting homeliness of diction and syntax through the use of rhythmic means that create such tension. This is not the place to debate the relative merits of Southey’s and Wordsworth’s versification. It may be worthwhile to note here, however, that from Wordsworth’s point of view Southey’s passage of circumstantial narrative (like his own in the passage quoted from “Michael”) lacks the kind of passion that would justify all of this overflowing of physical boundaries and challenging of the integrity of the line.

Wordsworth’s practice in “Michael,” in Lyrical Ballads as a whole, and indeed throughout the Poetical Works shows that he tended to reserve such verse—heavily enjambed and with frequent midline full stops—for poems or passages of poems in which the play of the speaker’s emotions is of the essence. Such verse is not used merely to give a kind of counterbalancing rhythmic license or formal status to poems on homely subjects. In Lyrical Ballads, the only poem approaching Southey’s in the frequency of enjambment and use of midline full stops both is “Tintern Abbey,” in which the practices clearly are employed in the service of expressive and emblematic ends.10 The passage in the poem in which these devices appear most frequently is, predictably, the conclusion, in which the voice of the speaker expresses his hope and faith that the fleeting glimpse he has had of the permanent integrity of his experience will not wholly pass away:

Nor, perchance,

If I should be, where I no more can hear

Thy voice, nor catch from thy wild eyes these gleams

Of past existence, wilt thou then forget

That on the banks of this delightful stream

We stood together; and that I, so long

A worshipper of Nature, hither came,

Unwearied in that service: rather say

With warmer love, oh! with far deeper zeal

Of holier love. Nor wilt thou then forget,

That after many wanderings, many years

Of absence, these steep woods and lofty cliffs,

And this green pastoral landscape, were to me

More dear, both for themselves, and for thy sake.

(ll. 147–60)

Upon the assertion that this deeply personal experience is in fact communicable to his companion (and, by implication, to posterity) rests to a significant degree Wordsworth’s entire poetic project. Appropriately, the stylistic resources used in the service of the assertion are extraordinary, even within the context of this most prosodically complex of the Lyrical Ballads. Of the fourteen lines that make up this passage, ten are enjambed (64.3 percent; the ratio in the poem as a whole is 160/89, or 55.6 percent); six full stops occur in midline positions, compared with only one (the final stop) at the end of a line (compared with 27/14 in the poem as a whole). The effect of the ending, rhetorically, is that of a single powerful assertion of the power of remembrance, continually augmented and revised: “Nor, perchance,” “rather say,” “Nor wilt thou then forget.” The effect of its prosodic character is to embody in the physical experience of reading (and hearing) the tension between assertion and revision—or the sense of confident summation tending toward closure—and the countertendency toward an open-ended avowal of the inability to fix the meaning of the occasion. The extraordinary degree of complexity in the interplay of metrical frame and syntax serves extraordinarily complex ends. Such passages, expressive of a complex interpenetration of thought and feeling, demand to be internalized more than simpler passages do, to be felt and remembered in all of their physical details. Such a demand is appropriate, because to a considerable degree the meaning of the passage is dependent on the reader’s participation (along with the interlocutor) in the experience of just this kind of interpenetration and on his or her remembrance of the complexity of thought and feeling that is the motivating tension in the poem.

The only other passage in “Tintern Abbey” that approaches the ending in the degree to which metrical and syntactic units are in opposition is the beginning. In lines 1–23, fourteen lines are enjambed (60.9 percent) and five of six full stops are medial (83.3 percent; compare 65.8 percent for “Tintern Abbey” as a whole; 47.2 percent [143/303] in the Lyrical Ballads sample). This coincidence in tendency in the first twenty-three and the final fourteen lines may in fact help to account for the full sense of closure produced by the final lines, even though their rhythmic character is unconventional for an ending; that is, although the final fourteen lines do not fulfill the usual expectations of closure—that at endings tension between meter and rhythm, scheme and realization will be reduced—they suggest a kind of completion by means of a return to the rhythmic characteristics of the beginning. More important for present purposes, however, are the different ends to which similar metrical means are employed in the two passages. In the conclusion, the tension between line and sentence as competing forms of organization is primarily an expressive indicator; in the opening, such tensions are more directly emblematic and are especially related to generic considerations.

As the length of the introductory verse paragraph itself makes a statement concerning its speaker’s ambitions and powers, it needs to be considered whole:

Five years have passed; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters! and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With a sweet inland murmur.—Once again

Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs,

Which on a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect

The landscape with the quiet of the sky.

The day is come when I again repose

Here, under this dark sycamore, and view

These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts,

Which, at this season, with their unripe fruits,

Among the woods and copses lose themselves,

Nor, with their green and simple hue, disturb

The wild green landscape. Once again I see

These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines

Of sportive wood run wild; these pastoral farms

Green to the very door; and wreathes of smoke

Sent up, in silence, from among the trees,

With some uncertain notice, as might seem,

Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods,

Or of some hermit’s cave, where by his fire

The hermit sits alone.

(ll. 1–23)

This paragraph accomplishes a type of fusion of subject and style of versification that is pointedly unlike anything else in the Lyrical Ballads, either in blank verse or rhyme. The speaker, in his graceful synthesis into a harmonious whole of disparate elements of the scene, attempts and accomplishes more than any other speaker in the collection. His imaginative fusion of past and present, landscape and sky, motion and stillness, natural wildness and circumscribed domesticity into a complexly unified picture of the landscape demonstrates exactly the type of mental activity that Coleridge implicitly singles out in Biographia Literaria as the force behind Wordsworth’s most impressive manner: “He [the poet, described in ideal perfection] diffuses a tone, and a spirit of unity, that blends, and (as it were) fuses, each into each, by that synthetic and magical power, to which we have exclusively appropriated the name of imagination” (BL 2:15–16). The verse paragraph—and the poem as a whole—depicts a man possessed of a “prospectiveness of mind” or a “surview” through which he is able to “foresee the whole of what he is to convey.” This foresight allows him “to subordinate and arrange the different parts [of his speech] according to their relative importance, as to convey it at once, and as an organized whole” (BL 2:58).

Wordsworth’s marshaling of the resources of rhythm and sound in the passage is, appropriately, designed to assert the speaker’s comprehensive powers. The paragraph consists of four sentences, each describing in its main clause a distinct aspect of the speaker’s perception: “I hear,” “I behold,” “I … repose / … and view,” “I see.” These sentences become progressively longer and more complex. The first is a compound sentence of thirty-seven syllables; the second employs a compound subordinate clause and is forty-three syllables long; the third sentence contains sixty-five syllables and uses three verbs, a subordinate clause, and three prepositional phrases; the fourth has eighty-one syllables and is a series of three dependent clauses each completing the main clause “I see.” Within these sentences, the placement of the pause is extremely varied but tends to fall late more often than early in the line. Nearly a third of the lines contain more than one pause (seven of twenty-three), and in the remaining lines the pause falls variously after the third (once), fourth (once), fifth (twice), sixth (five times), and seventh (three times) syllables. The multiple pauses tend to create the effect of a spontaneous, conversational tone while the tendency toward late placement tends to produce a slow pace.

As the speaker makes more and more connections among details, progressively building up to a unified whole, his method of describing becomes progressively more capacious. The careful, slow, and patient composition of a landscape complete unto itself finds its appropriate expression in the speaker’s amassing of his words in slowly paced, progressively longer and more complex formal structures. The whole is unified in large part through the repetition of key sounds (particularly by the repetition, four times, of the word “again”) that function (to expand on Wordsworth’s metaphor of metrical writing as “fitting”) as threads running through the paragraph, helping to make of the separate phrases a unified whole. The repetition of the consonant h— to take just one of many instances that might be used to illustrate this pervasive management of sounds—is a particularly important means through which Wordsworth underpins and patterns his speaker’s expression. The sound is used sparingly in early and middle portions of the paragraph: “I hear” (l. 2), “behold” (l. 5), Here” (1.10), “hue” (1.14). It is nevertheless sounded frequently enough to call attention to its presence as an important element in the structure of the paragraph. When, in lines 15–23, the sound becomes (along with s and w) a dominant consonant sound, it functions, as does the repetition of “again,” to unify the paragraph. The amassing in the end of the paragraph of key sounds used sparingly in previous verses parallels the steady increase in the length of sentences and works to reinforce the paragraph’s creation of a voice that seems to gain power as it progresses. Wordsworth thus underpins his speaker’s ability to build great things from least suggestions, ensuring that his reader will have aural, as well as cognitive, evidence of that power.

In a poem that attempts to create a monument to the power of time to create as well as to destroy, this subtle building up of discrete phrases into a unified verse paragraph produces an effect more important than mere harmony of sounds for the sake of harmony. The stitching together of these sentences, effected in large part through the tendency of repeated sounds to work against the onward temporal succession of the sounds of words, is an instance of, as well as a vehicle for, the speaker’s imaginative fusion of past and present into a single scene. Just as the speaker creates through images and figures of speech a representation of the ability of imagination to hold intellectually separable elements in harmonious suspension, so the repeated sounds (particularly those of the insistently repeated word “again”), by eddying back upon themselves, give structure to the temporal succession of the words. The thread of repeated sounds and syllables helps Wordsworth, in Ezra Pound’s terms, to cut a form in time,11 making the paragraph a union of temporal and spatial organization analogous to those described elsewhere by Wordsworth through such figures as the “speaking monument” of The River Duddon (3.3). The paragraph is not merely a description of a result of imaginative perception; it is an active instance of imaginative process.12

The opening paragraph of “Tintern Abbey” is extraordinarily complex not only in comparison with the verse of “Michael” or with the stanzaic poems of Lyrical Ballads and the Poetical Works but even within the context of Wordsworth’s blank verse as a whole. It therefore stands out not merely as a powerfully expressive use of language (though it is that, of course) but as an emblem of (and proof of) the operation of those very powers that the poem is engaged in attempting to define and assert. The heightened formal qualities of the passage function to elevate and foreground the medium itself in such a way that the powers of the poet as poet are made a subject of the poem in a particularly insistent way. These are, after all, “Lines Written … above Tintern Abbey.” The poet’s powers as a writer, as composer of internal and external landscapes in words, are as surely on display as are his capacities to think, feel, and remember. If “Michael” gives us the poet as storyteller, rehearsing a well-known tale, this announces the poet as shaper of hitherto unapprehended experience, giving body to the previously unarticulated through the music and mystery of verse. The blank verse of the poem is appropriately formal, lyrical magisterial. Its elevated style presents it as a masterpiece, in the sense of a work of art undertaken in part to provide “proofs of skill acquired by practice.”

In a poem about the ability of poetry to respond powerfully to loss, such proofs of the speaker’s control over the resources of his art are constitutive of meaning in a precise way: the formal composition of the lines, presented as having issued spontaneously from a state of heightened passions, is a kind of instance of the speaker’s paradoxical claim that his life to date has been (like the “wanderer” Wye) both perfectly free and powerfully determined. Will and necessity, spontaneity and pattern, passionate expression and the poet’s duty to shape expression into pleasurable poems are bodied forth in the very speech impulses and patterned sounds of the verse.

In the first chapter, I suggested that Wordsworth’s is an aesthetic based not so much on unity as on significant diversity, the end of which is the presentation of as wide a variety of poetic speakers as may be pleasurably encompassed by the synthetic and sympathetic mind. Wordsworth’s complex and odic blank verse in “Tintern Abbey” is effective in part because of intrinsic tensions employed to effect and in part because, within the context provided both by rhymed poems and by the less formally complex, less passionate and elevated blank verse in the collection, it is extraordinary. Conversely, the presence of the blank verse of “Tintern Abbey” in Lyrical Ballads helps to bring out more strikingly the different relationship among speaker, subject, and audience that results from the formal simplicity of “Michael.” In “Michael,” the poet who is capable of the heightened verse of “Tintern Abbey” sets aside some of the devices of composition at his disposal in order to single out one among many sources of his power; in “Tintern Abbey,” the poet who is capable of the austerity of the verse of “Michael” provides a stylistically all-encompassing instance of the full power of the mental river into which the tributary represented in “Michael” flows.

“Michael” and “Tintern Abbey,” then, represent two effectively dissimilar adaptations of the same verse form to Wordsworth’s purposes in Lyrical Ballads: the “fitting” of language to metrical arrangement for the purpose of delineating, and encouraging sympathetic participation with, a range of types of minds or of individual minds under various circumstances and influences. And they are only two of many different kinds of blank verse in a collection that includes the dramatic blank verse of “The Brothers” (and of Coleridge’s “The Foster-Mother’s Tale” from Osorio), the Cowperian verse of “Poems on the Naming of Places” (see especially “There is an Eminence, of these our hills,” and “To M.H.”), and the highly rhetorical and sententious verse, anticipatory of the Wanderer’s speeches in The Excursion, of “The Old Cumberland Beggar” (especially its peroration).

Wordsworth’s blank-verse variety is clearly apparent even within individual poems in Lyrical Ballads. The 1800 version of “Animal Tranquillity and Decay, a Sketch,” for example, draws on prosodic means to present a pointed and abrupt change of focus and tone on the part of the speaker. (The poem in this regard anticipates the kind of purposeful dissonance that has been discussed above in connection with “The Sailor’s Mother.”) In “Animal Tranquillity and Decay,” as in “The Sailor’s Mother,” a speaker comments on the appearance of a person he meets on the road, drawing from that appearance a general preliminary impression. The “mein and gait” of the sailor’s mother make her “stately” and dignified; the old man’s “face, his step / His gait” form “one expression”:

… every limb,

His look and bending figure, all bespeak

A man who does not move with pain, but moves

With thought—He is insensibly subdued

To settled quiet.

(ll. 4-8)

The physical expression of the man, his demeanor and his movements, have a language of their own that “bespeaks” his character. The speaker, who may be regarded as a kind of translator into words of these outward signs and actions, finds in his subject an embodiment of one who has been “by Nature led” to a “peace” that he describes as “perfect.” The exercise of patience throughout a long life has become so habitual to the old man as to “seem a thing, of which / He hath no need” (ll. 11–12).

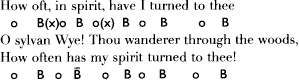

The speaker sums up his impression with an implicit contrast between himself (the “young”) and his subject:

… He is by nature led

To peace so perfect, that the young behold

With envy, what the old man hardly feels.

(ll. 12–14)

The artful antithesis of the speaker’s summation—its balance of the concerns of young and old, of the intense interests of “envy” and the supposed disinterestedness of the old man-is typical of the whole of the character sketch. Throughout the sketch, the speaker sets up balanced contrasts between free will and necessity, activity and passivity (the practice of patience leading to a state in which it seems that no patience is needed), and gain and loss (tranquility and decay).

These contrasts are couched in the first fourteen lines in highly patterned, prosodically subtle language. The opening “sketch” is in fact structured as a kind of blank-verse sonnet.13 It begins with discrete facts about the man’s appearance (the birds do not “regard” him; he “travels on”; his “face, his step, / His gait” form “one expression”), continues with reflections on patience and the meanings of the old man’s appearance, and ends with a summation neatly contained in the lines quoted above. The turn from description to reflection occurs, as would be expected in a poem in sonnet form, midway through line eight, dividing the first fourteen lines into a neat binary structure, octave and sestet.

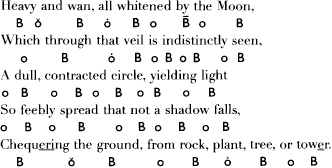

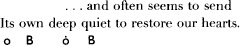

Within this larger pattern are many other patterns, all of which tend to present the speaker as adept in the habits of formal composition requisite to the kind of exemplary character sketch he has undertaken. A higher than normal incidence of enjambment (eight of fourteen lines; 57.1 percent) and midline full stops (four of six full stops are medial) help make the sketch as rhythmically impressive as any of the blank verse in the collection. These characteristics also help account for the sense of closure at the end of line 14, where the full stop is prepared for by the slowing effects of the pauses after unstressed syllables in lines 13 and 14 and by the use of the demoted third-syllable adjective in line 13:

Note, too, how the promotion of “that” and “what” in the two lines produces the effect of four strong beats per verse, drawing on the stabilizing effect of native measure and thereby contributing to the sense of binary structure on which sonnet form depends.

The sketch also achieves a kind of unity through frequent repetition of verbal sound—particularly alliteration, internal rhyme, and homoeo-teleuton. The repetition of third-person pronouns (“he,” “his,” and “him”) throughout the first fourteen lines (ten times) gives sonic evidence of the speaker’s insistent and minute focus on his subject. The repetition of initial p, from “peck” (l. 2) to “pain” (l. 6) to “patience” (twice, in ll. 10 an 11) to “peace so perfect” supplies a thread of sound underpinning the key transformation of the old man into an example of perfection. The final two lines achieve their sonnetlike summarizing power in part through the rhyme of “behold” and “old” that links lines 13 and 14.

An instance of line-ending homoeoteleuton is particularly significant:

… He is one by whom

All effort seems forgotten, one to whom

Long patience has such mild composure given,

That patience now doth seem a thing, of which

He hath no need.

(ll. 8–12)

The juxtaposition in the final feet of successive verses of “by whom” and “to whom” and the repetition of “patience” in lines 10 and 11 call attention through prosodic minutiae to an overarching thematic concern: the relationship between the old man as one who acts and as one who is acted upon. He is both an agent “by whom” effort has been forgotten through long exercise of patience and a creature of necessity “to whom” nature has “given” peace by leading him to his present state. Taken together, these various kinds of formal pattern help give the first fourteen lines an intense feeling of formal coherence. The sketch is as perfect a reconciliation of opposite or discordant qualities as ever Coleridge could want to see and hear.

Then comes the abrupt downfall.14 Lines 15–21 (end) of the poem suggest prosodically and otherwise that here, as in “The Sailor’s Mother,” the perfect “sketch” can only achieve its internal perfection and harmony through the exclusion of the subject himself. When the speaker asks the old man “whither he was bound” on his “journey” (note again, in the pun on “bound,” the speaker’s confidence in his ideal of the perfect relationship between self-determination and necessity), he receives an answer that speaks only of disharmonies and disruptions of peace and contentment, of war and an old father’s loss of a son:

he replied

That he was going many miles to take

A last leave of his son, a mariner

Who from a sea-fight had been brought to Falmouth,

And there was lying in an hospital.

(ll. 16–20)

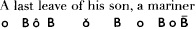

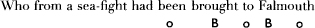

Line 18 provides the first metrical dislocation in the poem (there is in ll. 1-17 not even an initial inversion), and it comes in a particularly disruptive position:

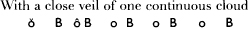

Such second-foot inversions, as has been mentioned above, are extremely rare because they are so dangerous to the metrical character of the line. The promoted ending of the line continues the effect of ill-fitting meter and rhythm and prepares for a further departure from the metrical set in line 19, where Wordsworth introduces an eleven-syllable line with a “trochaic” ending (a dramatic pentameter):

In short, Wordsworth could not have made the shift in kinds of blank verse more abrupt. Even the 1798 version, in which these lines are presented as quoted speech instead of paraphrase, is not as disruptive as is this change of pace in the voice of the speaker himself. It is as if the speaker’s very recollection of the effect of the old man’s unanticipated response has produced an emotional deflation affecting his powers of expression. He goes from blank-verse master to stammerer in meter as he recounts the excruciatingly prosaic answer of his erstwhile poetic and perfectly contented subject. The concluding passage is utterly devoid of figures of speech (even “going many miles” makes prosaic the “journey” in the speaker’s question) and uses no word or arrangement of words that would be out of place in the barest matter-of-fact speech. Wordsworth shows through stylistic dissonance that, whatever the speaker has captured of his subject, his conventionally unified sketch (in ll. 1–14) is just that a sketch. The concluding lines effectively break open the sketch, challenging the very aesthetic principles on which it is based and suggesting that the quotidian reality that is the old man’s existence must challenge (as must all human existence) the well-intentioned but ultimately inadequate attempt of art to represent it as “something loftier” and “perfect.”15 The ear cautions speaker and reader alike to see more clearly. The voice of the old man, like other voices of other men and women encountered by chance in Wordsworth’s poetry, admonishes the speaker, bringing him back to the “very world.” Through such means Wordsworth implies that the poetry that can adequately comprehend that “very world” is a poetry in which the desire for earthly perfection and the life lived in time and space struggle for dominance in the very music of the poem.

The range of styles within “Animal Tranquillity and Decay” is admittedly more striking and more productive of prosodic dissonance than is usual in Wordsworth’s blank-verse poems. In fact, the last seven lines were not retained by Wordsworth in reprintings of the poem in collected editions from 1815 through 1850. Whether Wordsworth judged that the juxtaposition of metrical styles was too dissonant (at least for the ears of his readers, if not for his own) or whether he decided that the internal tensions between youth and age, tranquillity and decay couched in the easy rhythms of the fourteen-line sketch were themselves sufficient to give the summation the desired effect of a too-perfect and too-neat closure, it is difficult to say. What is clear, however, is that the principle behind such widely various use of the same or similar metrical forms is in evidence throughout Wordsworth’s corpus. The presence of such diversity and such range in the blank verse of Lyrical Ballads (1800) suggests that a chief attraction of (and source of difficulty in) blank-verse composition is the opportunity it affords for the juxtaposition of diverse (even extreme) realizations of the same metrical pattern. The presence, for example, of the last seven lines of “Animal Tranquillity and Decay,” the first twenty-three lines of “Tintern Abbey,” the dramatic blank verse of “The Brothers,” the homely narrative verse of “Michael,” and the marmorial “Lines left upon a Seat in a Yew-Tree,” all in Wordsworth’s first substantial collection, make complexity of voice itself an issue of primary importance. In the more or less tense reconciliation of the discordant qualities of regularity and departure from pattern, in the easy or difficult fitting of phonetic material to abstract and predetermined forms, and in the fluidity or turgidity of the mind as it is expressed through the physical operation of speech reside a fundamental and infinitely complex kind of meaning in Wordsworth’s corpus.

WORDSWORTH’S “BEST SPECIMENS”:

“A NIGHT-PIECE” AND “YEW-TREES”

According to Henry Crabb Robinson, Wordsworth considered “A Night-Piece” (composed probably January 1798; published 1815) and “Yew-Trees” (composed 1804, 1811–14; published 1815) his “best specimens of blank verse.”16 Given Wordsworth’s characteristic precision of statement, such a description may be considered an invitation to consider this pair of poems, both of which appear in Wordsworth’s collected works as Poems of the Imagination, as together containing in small much of what is vital in and characteristic of Wordsworth’s most intensely lyrical and imaginative blank verse.17 A close focus on these two relatively short poems also will provide an opportunity to delve into some of the more minute levels of prosodic organization in Wordsworth’s blank verse. Whereas the first section of this chapter focused chiefly on Wordsworth’s habits in placement of pause and use of enjambment, this section will be concerned more immediately with significant instances of rhythmic dislocation, the structural integrity of individual verses, and patterns of assonance and alliteration.

In “A Night-Piece,” a speaker describes a “pensive traveller” who experiences an unexpected and intensely pleasurable moment of vision brought about by the breaking forth of the moon and stars from a thick cloud cover.18 The dynamics of the poem give it a clear four-part structure: an emotionally neutral beginning, in which the speaker describes a poetically unpromising overcast night (ll. 1–7); a rising action, as the traveller is “startled” by a rift in the clouds, and his eye, which has been “bent earthwards,” now is directed toward a “Vision” of “The clear Moon, and the glory of the heavens” (ll. 8–13); an emotional peak, in which the vision is described (ll. 14–21); and a falling action, as the traveller’s mind, “not undisturbed” by the “delight” it feels, “slowly settles into peaceful calm” (ll. 28–26).

Wordsworth says that he composed the poem extempore on the road between Nether Stowey and Alfoxden, and in DC MSS 15 and 16 it bears the title “A Fragment,” appropriate to the sense of unpremeditated overflow that the poem attempts to imitate. The versification is in fact as clear an instance as Wordsworth’s corpus affords of powerfully expressive and affective blank verse. The volatile and shifting verse rhythms and patterns of sound function primarily to convey the impression that the speaker of the poem is actually, in the process of composition, under the influence of the intense and delightfully disturbing emotions that the poem recollects. These elements of versification in turn serve to encourage the sympathetic participation of a reader in the dynamics of tension and release appropriate to the emotions expressed in the poem. The finished poem, that is, presents itself not merely as an account of the vision but as an invitation to the reader to participate in a reenactment of its emotional content and structure.

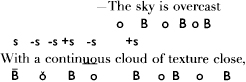

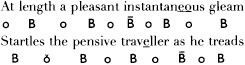

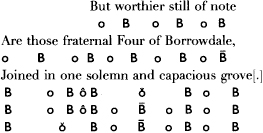

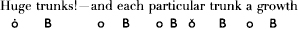

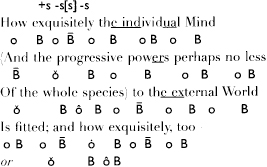

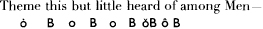

The first part of the poem contains virtually no metrical complexity, and therefore no metrical tension, apart from initial inversion (ll. 2, 3, 7), some promotion and demotion of stresses, and three instances of elidable syllables (underlined):

Even the variant structures—for example, the promotion of the initial syllable in the second line and the formation thereby of a relatively weak initial inversion pattern (the ubiquitous +s -s -s +s)—are appropriate to the nearly emotionless calm of the opening. Indeed, the line seems to be designedly gentle when compared with an earlier version (in DC MSS 15 and 16):

(Butler and Green, 276; 500-501)

Here, the relatively more disruptive stress-final pairing (-s -s +s +s) and the implied offbeat produce a kind of metrical tension, implying complexity of emotion, that Wordsworth evidently came to feel was out of place at this point in the poem. The revised version provides a more neutral metrical unit that will help provide in lines 1–7 the basis for an important contrast between the rhythm of the opening and the considerably more complex rhythmic patterns in the central two sections of the poem. Similarly, the list of nouns in line 7, in which “plant” is placed in an offbeat position between the semantically equivalent “rock” and “tree,” tends toward a leveling of stress values and a concomitant diminution of the rhythmic pulse and pace.

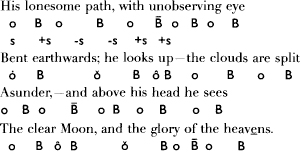

In part 2, increasing metrical complexity in the form of double and implied offbeats corresponds to increased emotional activity, as the plodding traveller is startled by the illumination of the previously dull and darkened landscape:

Line 11, as the scansion clearly shows, contains a particularly disruptive instance of a stress-final double-offbeat pattern interrupted by a strong third-syllable pause. Although the metrical set encourages the four-syllable group to be considered as a whole (with the implied offbeat compensating for a double offbeat), this realization sharply splits that normal pattern asunder. An even more unsettling challenge to the metrical set occurs in line 13, with an instance of an effect that has been labeled the diabolus in prosodia (or the metrical equivalent of music’s diminished fifth, or “devil’s,” interval)—second-foot inversion.19 The expressive and emblematic effects of the prosodic breaks in these lines are sufficiently obvious. The “gleam” breaks forth, jolting the “unobserving” traveler, the speaker, and the reader out of the well-beaten, earthbound, and continuous path. It transforms the familiar and predictable into something extraordinary and celestial. There is no more familiar path for the voice to take than the pentameter, and there are few disruptions more threatening to the form itself than the kind Wordsworth introduces here.

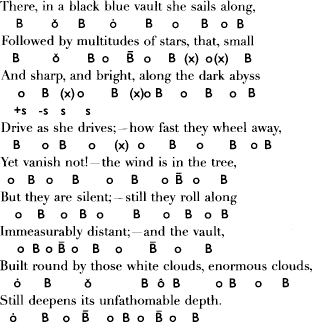

The challenge to the metrical set initiated in this second part of the poem develops in part 3 into a realization as close as Wordsworth comes in his pentameter to a genuine departure from “the regular rules of the iambic” and from his own rules concerning placement of pause. Here Wordsworth takes advantage of a number of devices—chiefly enjambment, multiple midline pauses (including pauses in eccentric positions), and effective placement of polysyllabic words—to continue and develop the effect begun in part 2 of extraordinarily energetic speech rhythms. The use of short phrases in this passage is especially effective, as it reproduces in performance the very motions of the speech organs appropriate to the visionary experience. The scene is literally breathtaking:

The phrase “Drive as she drives” is in the context of Wordsworth’s metrical set an astounding departure. The second-foot inversion is disruptive enough; a sequence of four consecutive atypical syllables occurring at the beginning of a line threatens to break the back of the meter. In this case, the combination of strong enjambment before and a midline full stop after the atypical sequence helps to neutralize its disruptive tendencies. The enjambment and the unconventional pattern do, however, tend to prohibit rapid or rhythmically regular pronunciation and make the full stop after “drives” as emphatic as possible. All of this works to emphasize by way of extreme contrast the rapidity and regularity of the second part of the next full phrase, in which the speaker reaches an emotional peak in the contemplation of a vision of profound permanence vested in eternal motion, of infinity and containment both: “how fast they wheel away / Yet vanish not.”

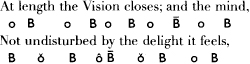

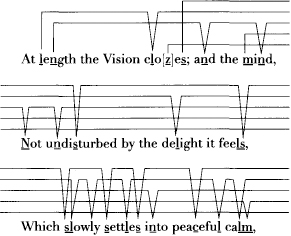

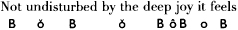

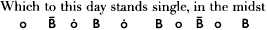

Part 4, introduced by an echo of the transition that began the movement from lesser toward greater metrical complexity (“At length …”), concludes the poem with a return to the rhythmic regularity and longer phrases of the opening:

Only the phrase “not undisturbed by the delight” disturbs the return of realized stresses to their theoretically proper places. The hint of a very rare triple offbeat caused by the placement of the preposition “by” in a beat position is a ripple in the calm that Wordsworth achieved in revision. In DC MSS 15 and 16, the line appears thus:

Introducing the contrast between “delight” and the “peaceful calm” to which the disturbance gives way, Wordsworth also achieves a rhythmic flurry appropriate to the contrast he obviously wishes to make in the structure of the experience between the heightened emotion of the vision and the deeper calm to which it gives way. Elsewhere in this concluding passage, and especially in the two final rhythmically unbroken lines, the prosodic regularity of the opening section returns, marking the slow subsidence of the speaker’s emotions after the “Vision closes.”

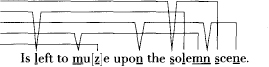

Contributing to the sense of fulfillment and closure, too, is a slow gathering of alliteration, especially on the sounds [z] and [s] and the sonorant consonants m, I, and n:

Also contributing is the repetition at the end of the final two lines of the rhythmic pattern +s -s / +s ( / = word boundary)—”peaceful calm,” “solemn scene”—in which the first two syllables form a disyllabic adjective and the last a monosyllabic noun. The effect, a repetition of identical rhythmic and syntactic forms with different sounds, might be called a “stress-contour rhyme.” More will be said below about this pattern in the discussion of the ending of “Yew-Trees,” including evidence that Wordsworth acknowledged its use and effectiveness in Milton. At present it may be sufficient to note that the identical grammatical and rhythmic structure at the end of successive lines is as close as one can come in blank verse (short of a Shakespearean scene-ending couplet, that is) to the sense of closure supplied by a couplet in rhymed verse.

The four-part poem, brief enough to be apprehended as a single rhythmic, sonic, and syntactic whole, proceeds, then, from rhythmic simplicity to extreme complexity and back, giving at the end a sense of return to the beginning, but with a difference. The rhythmic regularity that in the beginning was appropriate to the experience of the “unob-serving eye” is now the embodiment of feeling appropriate to the eye disturbed and then made quiet and solemn by an intervening vision of a sublimely immeasurable abyss in which action and stasis, sound and silence, are one. The structure helps convey through the very rhythmic impulses of the poem a sense that the state of mind embodied at the end of the poem is not different in kind from—and in fact is inextricably connected with—the common and everyday operations of mind with which the poem began. The delight produced by the vision, in other words, is the effect of the whole movement from and return to the everyday and is intended to produce a sense of the potentially heightened significance of—or the “glory” in—the common. Physically, the poem departs sharply from and returns completely to the common rhythms of the metrical set, creating through the process a new sense of the potential richness of that constraining set of conventional expectations.

“A Night-Piece” is impressive and effective in large part because its clearly individuated voice finds expression by means of an extraordinary degree of strain on the metrical set. The versification of “Yew-Trees,” the other half of Wordsworth’s “specimen,” is founded on a very different relationship between expressive impulses and metrical restraints, the passion of the subject and the passion of the meter. Indeed, the prosodic dissimilarity of the two poems suggests that extreme—variety even contrariety—is precisely what the poems, as “specimens” of blank verse, were intended by Wordsworth to exhibit.

In contrast to the speaker of “A Night-Piece,” the speaker in “Yew-Trees” is, as has frequently been noted in recent criticism of the poem, curiously impersonal and unindividuated. In “Yew-Trees,” differences between the single ancient yew, the “pride of Lorton Vale,” and the “fraternal four” of Borrowdale—which form an “umbrage” “not uninformed by Phantasy”—spark a meditation that tends to deflect attention away from the speaker and toward the relationship itself and its implications.20 The poem seems almost to exist to provoke and sustain consideration of relationships between the one and the many, individual act and communal gathering, historical individuals (“Um-fraville or Percy”) and timeless allegorical figures, war and “united worship,” pride and “fraternal” feeling, substance and shadow. Its pleasures, it might be said, are more purely intellectual than are the more immediate and sense-induced “delights” of “A Night-Piece.” Indeed, Lee Johnson has gone so far as to argue that at its deepest levels of organization, the pleasures of “Yew-Trees” are the pleasures of geometrical contemplation.21

The speaker of “Yew-Trees” recedes, as Theresa M. Kelley puts it, with the effect of foregrounding tensions between the sublime otherness of singularity and the beauty of containment.22 Appropriately, then, the prosody and music of the poem depend relatively little on the most disruptive kinds of variation—dislocations of stress pattern—and more on subtleties of phrasing of a kind that tend to reveal the abstract metrical underpinnings of the language, placement of pauses, and patterning of vowel and consonant sounds. The rhythmic pulse remains relatively constant throughout.

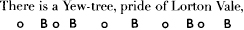

In “A Night-Piece,” five of twenty-six lines employ implied offbeat and pairing formations (-s -s +s +s, or +s +s -s -s). Only three such formations occur in the thirty-three lines of “Yew-Trees.” Their sparing use calls special attention to them, not so much as indications of the speaker’s passion (although they are that) as places of particular conceptual importance pointing emblematically toward thematic concerns. The first two instances occur at the very beginning: