I confess: in the eighth grade, I wrote a poem about chocolate cake. My mom pulled the cake out of the oven, and it was just so, I don’t know, gooey, sitting there, wafting cocoa scents that would tempt an ascetic. All evidence of that poem has now been destroyed, though it took a lot longer to realize the silliness of my stanzas than it did to scarf a few slices of cake.

My mom didn’t seem surprised by the poem. After all, I was the person who, at three years old, invented an ingenious new way to lick the batter out of the bowl: by putting it on my head, with my tongue stretched out to catch the chocolate as the aluminum rotated (spatial intelligence was never my strong suit). After I’d lacquered my hair with batter, my mother threw me into the bath. Needless to say, I ended up with a mouthful of soapy water instead of endless cocoa.

Flash-forward a few decades. I spotted a small chocolate shop in Portland, Oregon, and just had to check it out. When I walked in, though, my heart almost stopped. The walls brimmed with packages so brightly colored they almost bounced off the shelves, jars of sweet-looking nectar beckoned, and a few fulfilled faces sat sipping something dark and dreamy.

“Cacao. Drink chocolate,” the store’s sign said.

“Yes,” I replied.

On that first visit I timidly bought a bar from the huge collection, judging it solely on its pretty wrapper. “Are you sure you don’t want to try anything?” the salesperson asked as I retreated into the cool evening.

That night, after devouring all of that delectable chocolate in my Airbnb apartment, I couldn’t sleep. And it wasn’t from a sugar high. This stuff was different from the Snickers bars and chocolate hearts that I was used to. It was darker, more flavorful, more real. I’d had enough of truffles and candies with creams and fillings. It turns out they mask the real treat: the chocolate.

But what did the guy at Cacao mean when he offered to let me try something?

I couldn’t stay away for long. The next day found me waiting at the store when it opened at 10 a.m. My new best friend, co-owner Aubrey Lindley, an effusive, brown-haired 30-something, walked me through bite after bite of chocolate. “This 75 percent Madagascar from Patric is really fruity,” he told me as he handed me a square.

I nodded, but he could tell I was lost. “The beans are from Madagascar,” he explained. “That country is known for cocoa with a strong, sweet acidity, and Patric knows just what to do with it.”

I put the square on my tongue, and under the dominant chocolate flavor, it tasted bright, almost like a raspberry. This wasn’t your after-dinner Dove chocolate heart with an inspirational message. Beyond all the complex flavors (even though there were only three ingredients: cocoa, cane sugar, and cocoa butter!), the darkness was different too. Hershey’s Special Dark hits only 45 percent cocoa, and this bite measured 75 percent. Still, it tasted smooth, sweet, and creamy, even without any milk.

Aubrey watched my face. “Try a nuttier chocolate,” he said, breaking off a piece of Dandelion’s bar from Mantuano, Venezuela. I closed my eyes. Roasted nuts. Like the most decadent, tiny fudge brownie that has ever existed.

“What’s, like, the weirdest thing you have?” I asked him. Clearly I was getting more comfortable with this whole idea of eating chocolate for free.

Aubrey let out a wild giggle. “This one,” he said, pulling an Amano Dos Rios bar off the shelf. “It’s like licorice.”

It turns out that chocolate, like beer and coffee (and wine, our old snobby friend), holds many different tastes. Berries. Citrus. Nuts. Leather. Grass. A number two pencil. As Aubrey placed different squares side by side, I could taste the entire world in chocolate.

And it’s no longer coming only from France or Belgium or even good old neutral Switzerland. American makers now match and even exceed the masterpieces from big European companies like Valrhona and Pralus. This new movement of bean-to-bar makers produces bolder, bigger chocolates. Distinctly American chocolates. Just as craft beer and specialty coffee have taken America by storm, with small-batch makers creating products that take taste to a higher level, chocolate is evolving too. We’re increasingly turning to the darker stuff to satisfy our more sophisticated palates. Makers of small-batch bars from the bean are en vogue from coast to coast, boldly transforming the super-sweet candy bar of your childhood into a grown-up treat. Big companies have started to follow suit, as have a bunch of specialty stores around the country and even regular old grocery stores. In other words, it’s the golden age of chocolate.

Two hours later I waddled out of the store with enough theobromine to take out a pack of wild dogs, and with a new determination to find the best of the best. I wish I could say my quest was grounded in some intellectual purpose or humanitarian good, but nope, I just wanted to eat more chocolate.

Back at home, I gleefully cleared out black beans and canned tuna from the pantry’s biggest shelf to make room for bars from Askinosie and Dick Taylor and Fruition. Sure, I could eat chocolate until I was brown in the face. But finding the best chocolate from the best makers, and understanding what I was tasting? Well, that was a different story.

This book has grown out of my journey to explore the world of American craft chocolate. After years of learning on my own, I launched a site called Chocolate Noise that cuts through the noise of hype, reviews, and top 10 lists to capture a moment in time, with long-form profiles of the best makers in the country as well as timely snippets about chocolate today. But I’ve realized that it’s not enough. There isn’t a good in-depth guide to the world of craft chocolate.

That’s why I’ve written this book. Each chapter highlights unique aspects of bean-to-bar chocolate and its makers, from the difficulty of roasting beans to the beautiful art on the labels. Read the stories of makers like Dan and Jael Rattigan at French Broad, who drove across the country in an RV converted to run on used vegetable oil in order to start a new chocolate-filled life. They eventually opened the most delectable chocolate café in the country, where you’ll find chocolate bars as well as chocolate cake, brownies, ice cream, cookies, truffles, mousse, and more. Or Alan McClure of Patric Chocolate. Though he is already a master of making chocolate, he is so enamored with the science of the stuff that he’s working on a graduate degree in food science. Hear about chocolate pioneers like John Scharffenberger and Robert Steinberg of Scharffen Berger Chocolate Maker, who coined the phrase “bean to bar” and inspired a generation of makers, as well as Mott Green of the Grenada Chocolate Company, who after living as a homeless wanderer for years found himself on the beach in Grenada, foraging wild cacao pods. He eventually created a worker-run co-op that sails chocolate around the world.

You’ll also find recipes intended to be made with craft chocolate and high-quality cocoa, like the single-origin brownie flight from Dandelion Chocolate, cocoa nib ice cream from James Beard Award–winning cookbook author Alice Medrich, and the grown-up’s PB&J truffle from James Beard Award–winning pastry chef Michael Laiskonis. I hope that this book will be a resource for chocolate-crazy people across the country, and the globe.

Because, going back to my favorite book and movie of all time, Charlie was onto something when he chose that solid chocolate bar instead of candy in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. First off, he found his golden ticket. But he also predicted the next big movement in the artisan food world: pure chocolate, made from the bean.

A few years ago, while eating a bar of bean-to-bar chocolate with my best friend, she asked me a question that changed my life: “What do you do with bars of craft chocolate besides eat them? Like, when you get bored with eating them, is there another way to use them?”

Bored?! With eating chocolate bars?

I had never heard of such a thing. But then I started to think about it. I love candy, cakes, and cookies as much as the next person (okay, probably more). What if there was a way to enjoy this new bean-to-bar chocolate in other forms besides bars? Some chocolate makers and chocolatiers have started to experiment with making truffles, bark, brownies, and other treats out of small-batch chocolate. But I want you to be able to enjoy these at home too.

My favorite pastry chefs, chocolate makers, and chocolatiers designed the recipes in this book so that you will be able to taste the flavor notes of the chocolate in all of their beauty, and you’ll often see comments about which origins to use. So the bright, fruity notes of a Madagascar bar will pop in the finished drinking chocolate, and the deep nutty notes of a Venezuela will sing in the single-origin truffles. Take those origin notes as suggestions, not orders, and play around with them as much as you like. After all, chocolate should be fun!

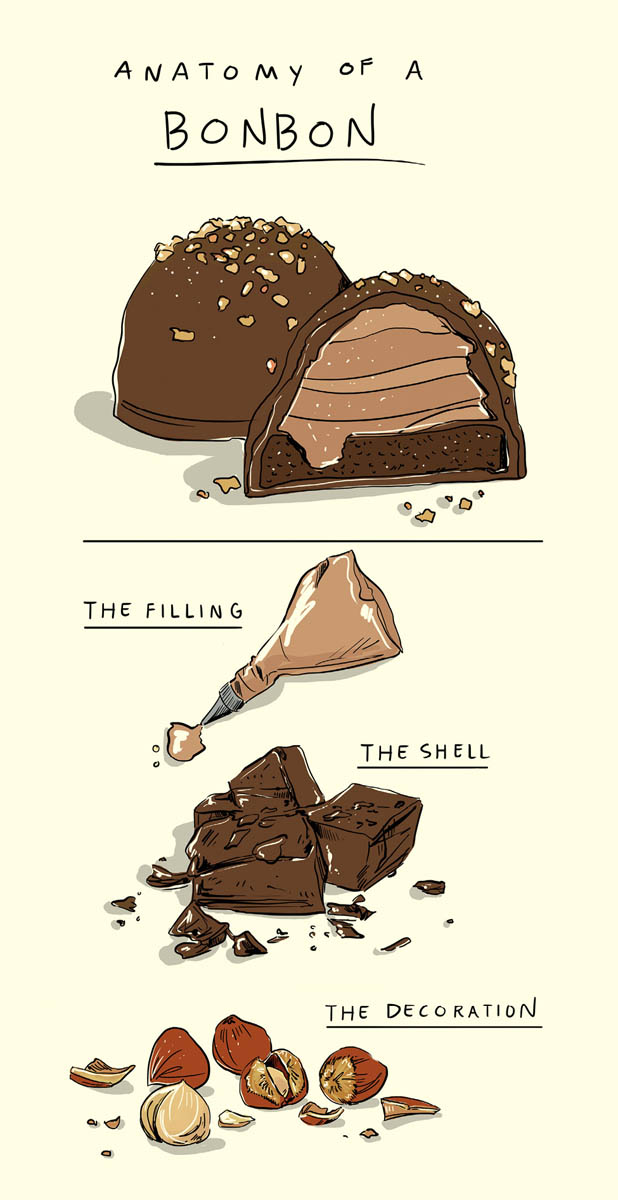

Keep in mind that some bean-to-bar chocolate does not have additional cocoa butter. Cocoa butter adds fluidity, so chocolate without added cocoa butter might be thicker when melted and harder to temper (see here), and possibly a bit harder to work with when making truffles and bonbons than couverture chocolate (which is made with a high percentage of added cocoa butter). For some of the recipes (like the bonbons), it might make more sense for you to seek out bean-to-bar chocolates made with added cocoa butter (look for it on the ingredients list).

Also, I know that bean-to-bar chocolate is expensive. Making chocolate treats at home is an investment, but I’ve tried to keep price in mind with these recipes. Some bean-to-bar makers and stores sell chocolate and cocoa powder for baking; check out my list of the best places to find bean-to-bar chocolate in bulk.

Most of these recipes are pretty straightforward, with just a few ingredients. That’s why it’s even more important than usual to use the freshest ingredients you can find, from local sources whenever possible. A simple drinking chocolate will taste even more delicious when it’s made with brand-spanking-new whole milk straight off the farm near your house, for instance. The same goes for ice creams, truffles, brownies, and, well, everything. Those ingredients will make high-quality chocolate taste even more high quality. And you’ll make everyone jealous of your mad baking and chocolatiering skills. In fact, I’m already jealous!

Note that the recipes are rated easy, medium, and advanced. Easy means the recipe is a no-brainer, and I have total faith that you can make it as a beginner. Medium means it’s a bit more complicated but still pretty straightforward. Advanced doesn’t mean that it’s impossible, just that there are many steps or that you need to be hypervigilant about reading the recipe ahead of time. After all, working with chocolate can be a bit tricky. But I believe in you!

To help you get started, the following pages offer a few tips on melting and tempering chocolate. Once you’ve tempered your chocolate, you’re ready to make bonbons and truffles. You’ll probably notice that the bonbon recipes in this book have different instructions. I’ve tried to showcase a range of ways to make them at home. I recommend trying all the methods, picking your favorite, and then applying that to the other recipes.

Always check the temperature of the oven using a secondary thermometer to make sure your oven temp is accurate. And be sure to let the oven preheat. You want its walls and floor to get hot so that when you open it, the oven doesn’t release all of its heat immediately.

Most of the recipes in this book call for melting chocolate in some capacity. You can do this in either a double boiler or a microwave. Always start by chopping the chocolate into smaller pieces, and, especially if you’re using the double-boiler method, keep it far, far away from any water (if chocolate touches water, it will seize — that is, it will get clumpy).

If you’re using a double boiler, bring the water in the bottom pan to a gentle simmer, set the top pan in place, and add the chopped chocolate. Heat, stirring occasionally, until it is melted. Note that if you don’t have a double boiler, a stainless steel bowl set over a pan of gently simmering water will work just as well.

If you’re microwaving, start with about 30 seconds to 1 minute, depending on the amount of chocolate. Then microwave in 10- to 15-second intervals until the chocolate is almost completely melted. Finish up with 5-second intervals to make sure you don’t burn the chocolate.

Heat chopped chocolate in a double boiler.

Stir the chocolate occasionally until it is melted.

I thought chocolate was always in a good mood, but it turns out it can lose its temper. (I know, I know, I’m probably the millionth person to make that joke.) What exactly does it mean to temper chocolate, and why is it important? I like artisan candy maker Liddabit Sweets’ analogy: To construct a sturdy building, you want to use bricks that are high quality and all roughly the same size. Well, chocolate is partially made of cocoa butter, which is crystalline, and in this case, you want all the crystals to be the right kind and about the same size (Form V, if you want to get technical). This is the effect of tempering. As a result, tempered chocolate will be shelf-stable, with a nice snap and sheen. Untempered chocolate will be dull and mottled and will bloom easily.

I highly recommend buying an infrared thermometer, which will tell you the temperature of anything (especially chocolate!) in less than a second. An instant-read digital thermometer will also work. Don’t make the same mistake I did when I first started working with chocolate: avoid old-school candy thermometers and meat thermometers. Chocolate is finicky and requires exact temperatures, quickly.

Bloom is a whitish appearance and chalky texture caused by poor storage or care. Sugar bloom is caused by moisture coming into contact with the chocolate; the chocolate will look dusty. Cocoa butter bloom is caused by poor tempering, faulty storage, or changes in temperature; the chocolate will turn powdery gray, white, or tan and feel soft and crumbly. With cocoa butter bloom, the chocolate isn’t ruined; it can be remelted and retempered and will be as good as new. With sugar bloom, you’re out of luck.

So how do you temper chocolate? I like to use the seeding method, which involves the following steps.

Seed the melted chocolate (above). Test with parchment paper (below).

If the melted chocolate has dropped to the appropriate temperature but there are still chunks of unmelted chocolate in your bowl, you have two options: fish them out or place the bowl in the microwave and heat it for 5 to 10 seconds to warm up the chocolate a bit more.

If the temperature is still pretty high and all of your seeds have already melted, you can add a few more. Ideally, though, you want to add them all at once.