THE TWO MOST IMPORTANT THINGS to explain about religion are why there are tens of thousands of religions today on planet Earth and why all of them are so resistant to the refuting evidence. The answer: religions are part of the human blueprint, just like speaking a language. Humans are religious because our ancestors who were religious reproduced more successfully than our ancestors who weren’t. This is the only explanation that works and is satisfying.

But now we are faced with a shocking conclusion: there is no such thing as any religion. There is no such thing as Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, Wicca, Sikhism, and so on. Yes, there are Christians, Jews, Buddhists, Witches, and Sikhs . . . but none of them actually practices a religion.

Among most of Earth’s religious people (which is to say, among most people), the idea that there are religions goes hand in hand with the idea that one religion is right and the others are wrong. Even among “enlightened” religious people who embrace some version of religious diversity, the idea persists that religion is correct. To get around the idea that the thousands of religions vary wildly, such “enlightened” people often say: “Perhaps we’ve all got our own interpretations of the fundamentally spiritual core of the universe, but that there is a spiritual core of the universe is not in question.” Indeed, it is common to argue as follows: “That so many people are religious, even if they differ considerably, surely points to a universal truth: that there is something holy and sacred, perhaps some being whom we but understand incompletely.” But we now know this is exactly like arguing, “That so many people eat large quantities of fat and sugar, even if they differ in what manner they consume them, surely points to a universal truth: that fat and sugar are good for us.” Most humans regard this latter argument as so silly that they cannot see the tight analogy between it and the first argument. Yet the two are exactly the same. The curious part is that so many of us let science tell us that fats and sugars are not good for us when consumed in large fried quantities, but turn a deaf ear to science telling us that there is no such thing as Christianity. True, we can explain why religion has the grip on us that it does, but few take that explanation to heart. Yet, when we do, when we allow the truth to wash over us, we see that there is no such thing as religion. There is no Navajo religion, no such thing as the religions of the Aboriginal peoples in Australia, the religions of the ancient Pueblo peoples, or the Chinese traditional religions. All religions are illusions supplied by our genetic makeup and the culture in which we were raised.

As mentioned previously, Richard Dawkins pointed out that we all know what it is like to be an atheist—when we consider religions other than our own, we instantly become robust atheists asking all manner of embarrassing questions of our non-coreligionists. I am urging us to go further, though—to see a deeper truth. In the privacy of our own minds, even if we outwardly embrace religious diversity, we can come to know exactly the truth “Religion X doesn’t exist,” where X is any religion that is not ours. Then, generalizing (“why should my religion, out of all them, be the correct one?”), we can jettison our own religion, too.

Atheism doesn’t really get at the heart of the matter. It is not that there are no gods or goddesses, but rather that there are no religions. What we call religion is people engaged in various rituals at various times of the year and at various stages of their lives, wearing various ritualistic clothing, and uttering various words and phrases. But this is all a kind of vast pretending, a pretending so complete that most of us cannot even see the pretense, a pretending fueled solely by our genetic makeup and our group membership. This is why I say there are, for example, Christians but no Christianity. Yes, there are people asking for, indeed begging for, forgiveness for their sins, but there is no one doing the forgiving and there is no supernatural mechanism whereby sins are forgiven. Indeed, there are no sins. Yes, there are Buddhists earnestly meditating in search of nirvana and the cessation of death and rebirth, but there is no nirvana to achieve, and no one ever has to worry about being reborn.

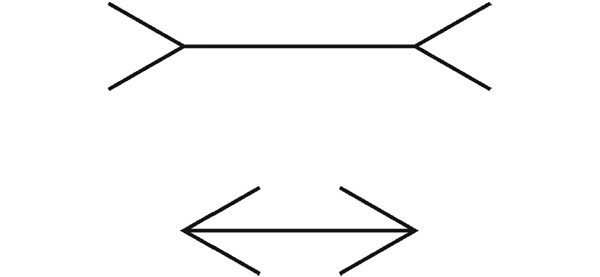

FIGURE 8.1. The Müller-Lyer illusion. Both horizontal lines are the same length, even though it is likely that you see the bottom one as shorter. Interestingly, this illusion, as well as many others, seems to vary across cultures: see, for example, Segall, Campbell, and, Herskovits, The Influence of Culture on Visual Perception.

Religions are therefore illusions, brought to us by our biology and our culture. Humans are prey to many kinds of illusions. This phenomenon is well known and well studied, though not well understood. Optical illusions, of which there are many, are the most famous examples. (See the Müller-Lyer illusion in figure 8.1.)

In the Müller-Lyer illusion, it is next to impossible not to see the two horizontal lines as being of different lengths. But if one measures them, one can determine that they are the same length. More strongly, backed by measuring, one can see that the lines are the same length, even though one cannot see the lines as the same length. Our conclusion from part 2 is that religions are another form of illusion, a special illusion to which humans are particularly susceptible. And I suspect that, just as with the Müller-Lyer illusion, it may be next to impossible to not perceive a divine hand guiding the world. But with science playing the role of measurement, we can come to see that there is no divine hand guiding the world and hence no point to worshiping.

The issues here are surprisingly and alarmingly deep. They cut to the heart of metaphysics, the philosophical discipline that attempts to describe the ultimate nature of reality. The most important question within metaphysics is “how much of ‘external reality’ is supplied by the human mind?” Or better: “how much of my ‘external reality’ is supplied by my mind?” The great French philosopher Descartes pointed out that the answer could be “perhaps all of it but me.” Descartes argued that with a bit of practice, we can doubt the existence of everything but our selves. (Our selves are exempt because something has to be doing the doubting, which is a kind of thinking.) The movie The Matrix shows vividly one version of this profound Cartesian truth. In the movie, all of what we consider ordinary reality is in fact a gigantic computer simulation downloaded into our brains, as many billions of us lie helplessly in vats of goo.

How much of reality is supplied by our minds? Fortunately, we can put this deepest and most difficult of all questions to one side here. We are only concerned with how much of religious “reality” is supplied by our minds. And the answer appears to be “all of it.”