Dear Colleagues,

We are Smokey and Elaine Daniels, a couple of longtime teachers. We have taught kids of all ages, and in many regions of the United States, for more decades than we care to admit. And right now, we want to share our single best teaching strategy with you.

This book is about a close-knit family of teaching and learning structures that changed our classrooms in very big ways. In fact, this is the single most important teaching idea we have ever learned. And we use it every single school day to structure powerful interactions among our students.

The core idea here is written conversation—a wide variety of letter types including handwritten notes, emails, dialogue journals, write-arounds, silent literature circles, collaborative annotation, threaded discussions, blogs, text messages, tweets, and more. We use these special writing activities to conduct a huge range of learning activities with our students. Year in and year out, the kids tell us this is one of their favorite ways to work, think, and interact with each other.

We know what you’re thinking: “Hmmm, this sounds like a kind of small idea.” Everyone thinks that before they try it. But we’re going to prove to you that letters—very broadly defined—are the single most neglected tool in our teaching repertoires. Here are some benefits this powerful genre of writing offers for your classroom.

Other than those things, letters aren’t much use!

So, are you having a little “been-there-tried-that” moment right now? Probably everyone who’s taught for more than a week has tried some kind of letters with his or her kids. Elementary teachers often try writing personal notes back and forth with students. Middle and high school teachers often have kids write literature letters” about their independent reading. And content-area teachers sometimes have kids write short notes in the form of admit slips or exit slips, handed in at the start or end of a class session.

But for most of us, these practices and other kinds of classroom correspondence somehow slipped away. Maybe we got overwhelmed by the sheer volume of letters the kids started sending us (in itself, a kind of proof of how much written conversations engage kids), or it simply slid out of our instructional routine under the crush of time, mandates, and new priorities.

So maybe we’ll call this an old idea well worth reconsidering.

A NEW OLD IDEA

Of course, classroom note-writing, both licit and illicit, has a long history in our schools. Primary teachers have always treasured (and happily answered) endearing notes from their kids, like the one below.

As a first-grade teacher, what are you gonna write back? C-minus for the spelling? More like, “Elizabeth, I love how you drew the hearts going through your mind!”

Figure 1.1

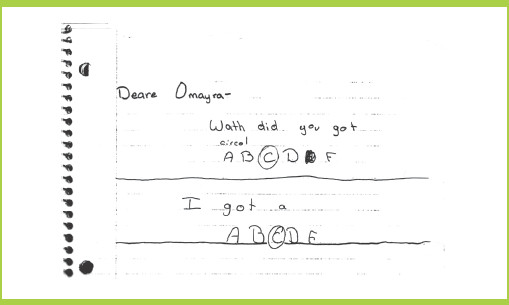

Kids have also found ways to pass notes to each other in class (an 1890 discipline guide advises teachers to administer five lashes for this crime). Perhaps the classic of this genre is the “whatdja-get” note.

Figure 1.2

Maria’s initial note to Omayra may be one of the archetypal letter types that kids have smuggled around classrooms since the beginning of time. But the girls’ easy familiarity with standardized test questions is as fresh as today’s headlines.

As kids get older, their notes to peers sometimes diverge even further from the curriculum. Here’s one page of a longer middle school conversation.

Figure 1.3

The matchmaker seems to be having some difficulty in setting up Craig with a girl called Lovely. Craig, seriously, no interest?

The point is that our students are already engaged in almost constant letter-writing. They emit texts, instant messages, Facebook posts, and even the occasional dinosaur-era email. First graders at home are sending notes and pictures to their grandparents, and their pals across town. Teenagers are writing scores of texts, trying to plan for some excitement around our tiresome lessons.

Figure 1.4

Today’s kids are writing letters ALL DAY LONG. They love it.

And, hey, if there is a form of communication that kids love, we teachers should exploit it immediately. If kids have a special vibration for that ancient/modern appeal of letters, a frisson for one-to-one writing, then let’s get them corresponding—about the curriculum we are teaching.

Here’s a kid-to-teacher note that is still personal and playful, but is also curriculum centered: It’s a quick book review with some self-imposed alliteration practice for good measure.

We’ll let 5-year-old author Andy Lopez conclude this demonstration.

Figure 1.6

In this note especially written for his kindergarten teacher, Andy draws a cowboy (CBOY) and his wolf (WF)—or maybe it is a dog saying “woof”? We’d have to have a conference with Andy to sort that out. And then there is a big empty box labeled “write in here” (RTINHIR), which means Please, teacher, write something in this special space I have made for you to answer my note!

The takeaway: Kids are dying to get into written conversations with their teachers and their friends. Let’s give them what they want!

NOTE to PRIMARY TEACHERS: Andy’s note gives a clue to how we do written conversations in early childhood classrooms. We use drawing as the core and push in print as kids are capable. Stay tuned.

THOSE LETTERS ARE CUTE, BUT . . .

Most of the student samples we’ve shown so far are energetic, funny, and purposeful, but not exactly academic. So how do we put letter-writing to work in helping kids learn the curriculum? Please read the exchange in Figure 1.7 between third grader Kerri and her teacher Chris Smith.

Lucky Kerri, lucky Chris! Here is a teacher meeting a child’s needs at so many levels that it almost makes your head spin. What a rich set of “mentor texts” Chris has created for this third grader, bathing her in the language of perfume, pearls, and sparkly things. She’s modeling adult thinking, writing, spelling, penmanship, and conversation—targeted directly at Kerri’s reading level and personal interests. In Common Core talk, we would call this a great lesson in explanatory writing.

While the official (and highly valuable) purpose of these daily “literature letters” is to support kids’ independent reading, there’s so much more going on. How deeply these two human beings are coming to know each other in this exchange. Our mentor-at-large Don Graves once said, “You are not ready to really teach a kid until you know 10 things about his or her life outside of school.” How speedily Chris is reaching that threshold.

Yes, we did say daily. Chris chose to exchange notes almost every day with every student, meaning that by the end of the year every child in her class had received more than 150 letters from their teacher. Whew! Now, we can hear you wondering, “How many students did she have anyway? Less than me, I bet! How much time did she spend on this? Where am I supposed to find the time to do this with my kids?”

Your instincts are right—writing individual notes to your kids is undoubtedly powerful, but it can become an overwhelming task. Chris used kids’ independent reading time each day to answer their letters; while they read books of choice, she wrote them notes. But that kind of frequency isn’t required; a little goes a long way. We’ve found that writing personal notes to your class once a week is about all we, and most merely human teachers, can handle.

But even in departmentalized middle and high schools, writing notes to just five kids a day still means that each student will get seven or eight personal letters from their teacher in a year. This is a fantastic step ahead of what we do now, and allows for some very effective individual coaching, mentoring, and guiding.

Far more important, over a school year and across the curriculum, is getting kids writing not to you, but to each other. Students must become each other’s best audiences, correspondents, sounding boards, and debate partners. Written conversation only achieves its full value when your kids regularly and fluently write to each other in pairs, in small groups, on chart paper around a text, on bulletin boards, on the class blog, and more.

“Writing notes to just five kids a day allows for some very effective individual coaching, mentoring, and guiding.”

KID-TO-KID LETTERS ABOUT THE CURRICULUM

Now, let’s take a look at some kids having a written conversation with each other, not the teacher. Sara Ahmed’s eighth-grade class in Chicago has been studying the origins of the Cold War and addressing the question, Which country was most responsible for initiating that conflict, the United States or the Soviet Union?

Today, Sara assigns students to read two short articles written in 1949, one by a Russian official named Dmitri Novikov and one by Henry Wallace, an American vice presidential candidate. Though these men drew different lessons from events, both acknowledged that America’s use of nuclear weapons in Japan had horrified many countries around the world. As a result, some nations felt their only choice was to organize a mutual defense against the seemingly reckless and trigger-happy Americans. This idea—that the United States might once have been viewed as a bully by much of the world—was truly novel to Sara’s 13-year-old students.

After kids read these eye-opening pieces, Sara asked them to join in an online written conversation for homework. “Everybody just get on our Edmodo site tonight and post once,” she instructed, as kids filled their backpacks for the trip home.

Here are a few of the 83 posts that resulted that night:

Sonali C.—I think Henry Wallace was trying to turn America into a communist country. J But, in all serious terms, I think Wallace was obviously on Novikov’s side and I think it was wrong too, as he wasn’t being patriotic to his own country (not saying everyone is. I’m not.) Maybe its because I’m an American, but I honestly think that America has its best intentions trying to make the world more peaceful. I think they do want more countries to be democratic but they don’t want take over the world like the Soviet Union.

Oct 6 | Edit | Delete

Max S.—i disagree. I actually think that he wasn’t. Throughout his speech, he had the same idea as Novikov, he thought that America just wanted power, which is want totalitarians want.

Oct 6 | Edit | Delete

Teagan L.—it was summarized, Max! His actual speech is probably a lot longer!

Oct 6 | Edit | Delete

Isabel L.—i think i agree with Max. If you look at what Henry Wallace says, would you trust the U.S? Both sides wanted to spread their kind of government. Imagine what both situations were. If you are the Soviet Union, you want power, and “the fruits of war” but your opponent has atomic bombs! And if you are the U.S, you just really want to maintain countries democracies and build and rebuild new ones. I agree with all of you that i think it was both their faults, but whose do you think it was, PRIMARILY?

Oct 6 | Edit | Delete

Emmy S.—I think that there’s a difference between being unpatriotic and disagreeing with some things that are happening in government. I don’t think that Henry Wallace was purposely being unpatriotic; he was speaking out about what he thinks is wrong with the way the U.S. was acting during this time. If he was the Vice President, he wouldn’t want America to completely change what it believes. I think he deserves more credit. It’s really hard to stand up for what you believe in, or to give your opinion when you think someone or something is wrong. I see his speech as more of a, I don’t know, wake up call, telling about how the U.S. might be portrayed to other countries.

I don’t think he would completely turn on his own country and it’s beliefs.

Oct 6 | Edit | Delete

Alejandro S.—But still c’mon, a lot of you people really need to re-read the Wallace speech. He isn’t on the communist side, he doesn’t want to spread communism, and he isn’t on the Soviet Unions side either. Wallace is basically saying that we all look terrible in the eyes of the world. The U.S. used the atomic bomb to basically trash all of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, they entered World War 2 at the very last minute! The US was basically the game changer in war. He’s saying that we are doing all these bad things and intimidating the rest of the world so they don’t mess with us or are at least on our side. Why did they give Latin America weapons? It wasn’t to be nice, it was basically a bribe to be on the United States side because Latin America needed weapons. The US is like, here we’ll give you some weapons just to be “nice” Latin America would then return the favor by being on the U.S. side. If you all refer to your maps you’ll see that all of Central American and South America is on the U.S side. Wallaces speech is a wake up call to the U.S to tell us all how we are portrayed by other countries which probably is the bully scaring other countries and trying to force Democracy on them like the Soviet Union is trying to force Communism on other countries

Here we see students thinking together in just the way that our Common Core standards call for: They are taking positions, arguing them in writing, and using evidence from the texts in support of their positions. But this is no inert five-paragraph essay; the energy in this debate is palpable. These kids are not dutifully fulfilling a teacher command; they are driven by curiosity, and they are quite enthusiastically doing the kind of work historians actually do.

Later in the school year, Sara and her kids reflected back on both their out-loud small-group discussions and their written conversations, and they co-created this chart. Look at the attributes they noticed in each variety of discussion.

“Here we see students thinking together in just the way that our Common Core standards call for: taking positions, arguing, and using textual evidence.”

Figure 1.8

This chart speaks volumes. First, it shows that Sara’s kids see spoken and written discussion as two sides of the same coin: both necessary and valuable and both with different advantages. But the right-hand column reveals some profound and unrecognized benefits of discussions that happen in writing.

• You can think before you “speak.”

• No one can be silenced. No “hog” can suck up all the air; everybody gets the same amount of time with his or her blank sheet of paper. Nobody can interrupt you.

• Kids who are reluctant to speak aloud have a way into the conversation.

• There’s less danger of yelling or bullying.

• It’s like writing notes = it’s fun!

• No distracting side conversations are possible (think how often “live” classroom discussions get undermined by such chitchat!).

• There is quiet that enhances concentration. When you read and respond to others’ notes, you can focus on their words and their thinking.

• Unlike conversations that evaporate into the air, written conversations leave a permanent record of the thinking.

Amid all the benefits, the kids also acknowledge some challenges with handwriting and understanding people’s tone in writing, versus out-loud speaking.

Now look what’s in the center: all the things that both kinds of discussions can provide.

Push our thinking

Ask follow-up questions

Connect

Back up our thinking with evidence

Convey emotion

We have our own version of the kids’ chart. It isn’t any smarter, but it is longer (see pages 18 and 19).

MEETING THE COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS WITH LETTERS

How can written conversations help our kids to meet the Common Core State Standards or the quite similar goals in non-Core states like Texas, Virginia, and Minnesota? Actually, the four writing models described in this book are not just helpful, but vital in helping students reach college and career readiness not just in writing, but in reading, speaking, and listening as well. While the K–12 literacy standards are highly integrated, we will try to pull them apart a bit here just to show how written conversations move kids ahead.

Writing Standards

The Common Core wants writing to be fully equal with reading in the time and attention it receives in school. That means that teachers must provide far more writing practice, experience, and instruction than students have typically gotten. Periodically crafting extended, formal, edited pieces is clearly required. But the Core also wants students to get constant practice with shorter forms of writing.

Writing Anchor Standard 10 (2012) asks that students “Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.” But most of the other writing standards focus on students composing scattered formal pieces to be painstakingly assessed and edited by teachers. But to become fluent, confident, proficient writers, students need far more writing practice than teachers can ever grade. Kids should be writing not every few weeks, but three, six, ten times a day. We think the Common Core really missed the boat on this subject, setting a way-too-low standard for writing practice.

“The Common Core wants writing to be fully equal with reading in the time and attention it receives in school.”

When students regularly join in structured written conversations with their teachers and peers, they get vital practice in thoughtful expression, the language of discussion and response, the process of building knowledge and analyzing ideas, ways of seeking evidence and developing supports, and presenting their thinking to a real, responsive audience. They are also under significant pressure to follow language, spelling, and organizational conventions, to be sure that their ideas can be easily understood by the various audiences who will be reading them.

The Common Core has especially high aims for the neglected modes of argumentative and explanatory writing. There’s a huge premium placed upon students’ ability to dig deep into a complex text and take a position, to develop an argument based upon evidence inside it, and to go public with well-reasoned and smoothly written arguments.

Look back to pages 13–15 and review the conversation among those middle school kids about the Cold War. They are staking out and defending positions, and supporting them with evidence from their two readings, trying to draw justifiable inferences from sources. Notice how the kids sometimes boldly question each other’s evidence or scold other people’s reasoning. Alejandro really holds his classmates’ feet to the fire: “But still c’mon, a lot of you people really need to re-read the Wallace speech.” And later he advises: “If you all refer to your maps you’ll see that all of Central American and South America is on the U.S side . . .” Written conversations like these are a made-to-order tool for developing first drafts of argument and explanation papers.

More broadly, students who have frequent opportunities to engage in extended written conversations are developing the fluency, confidence, stamina, and audience awareness they need to grow as writers. And they are also receiving the kind of immediate feedback that developing writers need, not just for initial motivation, but to grow and improve steadily. This is writing that’s real, writing that has consequences—and writing that’s engaging.

Reading Standards

The Common Core states that students at all grade levels should be reading more nonfiction text and more complex texts in all genres and should enjoy less teacher “spoon-feeding.” Kids should be challenged to make meaning from within the four corners of the text, without teachers cuing them in advance what to look for.

We also know from decades of research that students understand text better—and get better scores on individual standardized tests—when they have a chance to talk about their reading with classmates (Allington, 2012). Indeed, this is one strategy that proficient adult readers typically use when they are grappling with some challenging text; they seek others with whom to discuss it, they talk to someone, they “phone a friend.”

Getting in the habit of verbalizing your thinking as you read transfers to your cognitive repertoire; the more aware kids become of their own thinking (their connections, their inferences, their visualizations), the better readers they become, with others and on their own.

Speaking and Listening Standards

In our near panic to address the reading and writing standards, many teachers have overlooked the potentially transformational Common Core State Standards for Speaking and Listening. Among the goals for students at all ages are performances like the following:

Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grade level topics and texts, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly.

Come to discussions prepared, having read or studied required material; explicitly draw on that preparation and other information known about the topic to explore ideas under discussion. (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010, pp. 24, 49)

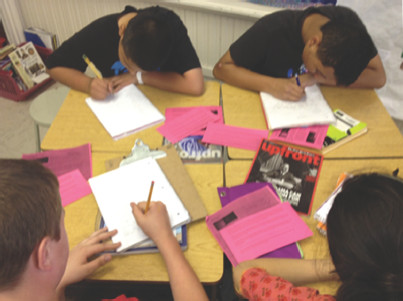

Jack Hollingsworth/Thinkstock.

In other words, having our students discuss curricular ideas in small groups isn’t an option under the Common Core; it is a straight-up mandate. You must do it and make it work. And one of the most effective structures we have for facilitating that kind of peer discussion is—guess what?—written conversations.

And let’s remember some other things those eighth graders taught us with their chart: Written discussions equalize airtime, invite in the shy kids, prohibit side conversations, allow you to be more thoughtful, and “last forever,” leaving tangible, assessable evidence of each child’s thinking.

ENGAGEMENT, BEST PRACTICE, AND WRITTEN CONVERSATIONS

Now, let’s think beyond the Common Core to the more general and eternal question: What does best practice teaching really look like? How can we set up classrooms and provide instruction so that kids learn deeply? Smokey and his colleagues Steve Zemelman and Arthur Hyde, in reviewing all the research on educational “best practice,” have identified the main attributes: classrooms where learners are genuinely engaged with experiences that are challenging, authentic, collaborative, and conceptual (Zemelman, Daniels, and Hyde, 2012).

But despite decades of research, a good deal of school time is still allocated to lessons in which the teacher either lectures to a silent class or holds “whole-class discussions,” during which a handful of students volunteer answers while the majority sleep. When the teacher is the “sage on the stage,” there is little positive social pressure for kids to commit, to participate, to join in the thinking. But no matter how ineffective, being that sage is still really hard work for us as teachers.

But have you ever heard that supposedly comedic phrase “School is a place where young people go to watch old people work?” While this notion grates on our every teacherly nerve, it does have some truth. Too often in school, we teachers are doing all the work—performing, presenting, spoon-feeding, cajoling, entertaining, all day long—while kids sit and watch, free to daydream and catch up on sleep.

Teachers who begin using written conversations during class are often amazed at how hard their kids are suddenly working. Engagement is built in; it comes standard. The structure is inherently involving: You get to write to a friend or two about a topic that’s interesting. When you sit down with a partner or a small group, there’s a high degree of positive social pressure to participate. You’ve got a classmate beside you who’s expecting a letter from you in just a minute—and a kid on your other side who’s about to send one to you. Being in a live letter exchange is brisk, fast-paced, and demanding of focus and attention. You’re in the middle of an active process that depends on your cooperation.

Teachers are also a bit surprised that during written conversations, they are actually free to wander the room, observe students at work, look over shoulders, and think about the activity. When you stop entertaining and get “off stage,” for more than a second or two, it’s a whole different world. As one delighted teacher told us, “The kids get so into these written conversations, I could probably go check my email if I wanted.” That would be wrong, but it’s often true: Written conversations are among the most challenging and kid-engaging structures we can mount in our classrooms.

In short, there is an imbalance in schools. We have lots of out-loud talk by teachers with low accountability for kids. Instead, we need much more written discussion by students with high levels of social and academic pressure to join in, think hard, and leave evidence of their thinking.

HOW THE BOOK IS ORGANIZED

In this introductory section, we have been trumpeting the benefits of curricular letter-writing, offering student samples, reviewing roots and research, and promising you many happy endings if you start using this interactive tool. In the book, we will show you four versions of written conversations, moving basically from early-in-the-year versions to later ones, from simpler to more complex (we prefer elegant), and from inside-the-classroom letters to correspondence that reaches out to the world.

Coming up next is a crucial and unrecognized application of written conversations: creating personal, friendly, supportive, and responsible relationships among your students at the start of the year (and all year long).

Chapter 2. A Community of Correspondents. Letters are a vital tool for building collaborative relationships in the classroom. We use correspondence to build acquaintance and friendship, to negotiate expectations and share responsibilities. To this end, we deploy letters between teachers and kids, kids and kids, and kids and teachers and parents; we share news journals; we set up classroom mail systems and message boards; and we write teacher-to-whole-class messages.

Next come four chapters that each addresses a specific type of written conversation that has proved useful in K–12 classrooms: mini memos, dialogue journals, write-arounds, and digital discussions.

Each of these chapters follows a similar template, offering the following:

• A definition of the structure

• An explanation of its origins and research base

• A “quick look” at a classic student sample

• A full launching lesson that shows the writing at work inside a real curricular topic, with teaching language you can try for yourself

• A generic, step-by-step instruction sheet for any teaching situation

• Detailed information on several subtypes and variations

• A list of practical management and problem-solving tips

• Plenty of student samples of this kind of letter in kids’ (and teachers’) own words

Chapter 3. Mini Memos. This is our name for the familiar family of admit slips, start-up writes, exit slips, and midclass writing breaks. These classic writing-to-learn jottings have always been implicitly letters; an exit slip is essentially a note to the teacher telling “what I learned today” or “what questions I have.” We leverage up the value of these quick notes when we give them official audiences and responders.

Chapter 4. Dialogue Journals. This is about pairs or partners—just two people—corresponding. We start small before we invite kids into write-arounds in larger groups. Dialogue journals can be either kid-teacher or kid-kid. Curricular conversations with peers are the primary use, but we can also engage students in correspondence with us, in which we coach, give feedback, or even address behavior issues.

Chapter 5. Write-Arounds. Also called written conversation or silent literature circles. Here, groups of three or four (rarely more) join in discussions of academic content—books, concepts, lab experiments—any common experience. These conversations happen in individual letters passed around a table, or on big sheets of chart paper where kids converse in the margins. Usually, these conversations switch from silent to aloud after a period of sustained silent writing.

Chapter 6. Digital Discussions. This chapter covers the tech-enabled versions of many forms in Chapters 3 through 5, plus correspondence that is uniquely digital, like email, texts, blog posts, and more.

LET THE STUDENT SAMPLES TEACH YOU

Over the past few months, we often joked that we were writing a picture book, not a professional text. And that’s partly true. Inspired by Lucy Calkins’ beautiful and groundbreaking The Art of Teaching Writing (1986), we’ve stuffed the book with scores of kid conversations, mostly in their own writing and drawing. A piece of student writing is always an artifact and often an artwork. Whatever it communicates, a letter exists as a made thing, perfect for a refrigerator door or a gallery wall. The samples we’ve chosen fully reveal the power and practicality of written conversation. If you let them, the kids’ writings will guide you just as effectively as the lessons, instructions, and tips we have also compiled here.

In a few spots, we have provided translations of kids’ handwriting; this helps those of us who do not speak the foreign language called “invented spelling” to appreciate primary children’s written conversations. We’ve also inserted marginal comments where we could illuminate students’ thinking, their writing strategies, and their social interactions.

So please slow down and enjoy the kids’ writing on its own terms: Savor the energy, notice the purposefulness, laugh at the intentional and the inadvertent jokes, notice the gentle gestures of friendship, applaud when the thinking deepens, and cringle at the spelling—but keep your red pen in its holster for just a while. Enjoy!

Sincerely yours,

Smokey and Elaine

P.S. Please be in touch with us via www.harveydaniels.com.