A simple flame-cut silhouette is a charming addition to any garden.

photo/©John Gregor

A simple flame-cut silhouette is a charming addition to any garden.

photo/©John Gregor

Welding is a practical skill that is also great fun. The number of welded items in our everyday lives is practically uncountable—the spot welds on the bodies of our automobile, the welded railing on our front steps, the superstructure of the buildings in which we work, and the bridges over which we drive. But welding also makes smaller, more delicate functional and decorative items possible, like patio chairs and trellises, wine racks and candleholders, baker’s shelves and headboards. The photos on these pages reveal only a fraction of what welding artisans have created with heat and metal.

The strength and malleability of steel makes it perfectly suitable for forming whimsical structures like this candelabra.

©Millet/Inside/Beateworks

Cutting and welding creates beautiful and useful household items, like this fireplace screen.

Photo courtesy of Sleeper Welding/Tom Sleeper

The costs involved in setting up a well-equipped home welding shop are comparable to setting up a well-equipped woodworking shop. A great advantage of welding is that the materials are generally inexpensive, yet you can create items that sell in shops for hundreds of dollars. Because fewer people are knowledgeable about welding, there is always a rewarding “awe” factor to showing off what you have created.

This book provides basic directions and step-by-step photos that illustrate the four major welding processes and the two major cutting processes. You also will find quick reference charts that describe electrode and filler wire choices, metals and their weldability, and joint and weld types. Suggestions for setting up a welding shop, detailed safety guidelines, and ideas for finishing your metal projects are also included.

Simple and graceful arches and trellises are easily made from mild steel. A few bends, decorative finials, and a handful of welds are all it took to make this simple garden archway.

Photo courtesy of Gardeners Supply Company

A variety of metals, shapes, and joining techniques were combined to create this beautiful artwork.

Photo courtesy of Gene Olson/Photo by Ytsma Photography

Best of all, this book includes detailed directions for 23 practical and decorative projects. You can make a welding and cutting table for your welding shop, a scrolled desktop lamp, a wrought iron railing, or a cute critter boot brush. You can practice your techniques and make accessories for your own home or as gifts. We also encourage you to use the project ideas to branch out and create your own versions of a baker’s rack, coffee table, or kitchen accessory stand.

These colorful puppies are cut from junked car hoods.

Photo courtesy of Lizard Breath Ranch, Inc.

Creating fanciful creatures from garden tools is a rewarding welding project.

Photo courtesy of Heebie GBS Metalworks

Scales of sheet metal, springy legs, and mesh trolleys—what a fun piggy collection.

Photo courtesy of Dave Johnson/Birds & Beasts

Old tools and recycled metal odds and ends make this gate geometrically pleasing.

Photo courtesy of Heebie GBS Metalworks

Old farm implements and spare parts are great sources of weldable material. This chicken shows what a little imagination can do with a pile of parts.

Photo courtesy of Dave Johnson/Birds & Beasts

The strength of steel allows for solid yet airy structures like this plant stand.

Photo courtesy of Gardeners Supply Company

Welding is all about heat, about using heat to melt separate pieces of metal so they will flow together and fuse to form a single, seamless piece. Regardless of the welding or cutting process, your ability to control the heat generated by the flame or arc determines the quality of your welds and cuts.

Certain terms are used to describe the heat and action of all the welding processes. The parts being welded together are referred to as the base metal. Additional metal, called filler, is often added to the weld. The molten puddle is the area of melted base metal and filler metal that you maintain as you create your weld. To have fusion of metals, the base metal and filler metals must be the same composition. Methods for joining metal without fusion are called soldering, brazing, and braze welding. These methods can be used to join similar or dissimilar metals.

Oxyacetylene welding and cutting use flames to generate the heat to melt the metal. Shielded metal arc, gas metal arc, and gas tungsten arc welding and plasma cutting use an electric arc for heat generation. With oxyacetylene welding, you have time to watch the puddle develop as the metal turns red, then glossy and wet looking, then finally melts. With the arc processes, the puddle forms quickly and may be difficult to see because of the intensity of the arc. It is important to have ample lighting and clear vision so you can watch the puddle and move it steadily.

Oxyacetylene welding

Penetration of the weld is also a critical heat dependent factor. A strong weld penetrates all the way through the base metal. Matching filler material size and heat input to the thickness of the base metal is important. It is easy to get a good looking weld that has not penetrated the base metal at all and merely sits on the surface. At the opposite end of the spectrum from a “cold,” non-penetrating weld is burn through—where the base metal has gotten too hot and is entirely burned away, leaving a hole in the base metal and the weld.

Heat distortion is a by-product of all welding and cutting processes. It is obvious that applying a flame to metal in the oxyacetylene process makes the metal hot—and the electrical arcs are actually four to five thousand degrees hotter than the oxyacetylene flame. When metal is heated it expands; when it cools it contracts. If not taken into consideration, this expansion and contraction may cause parts to move out of alignment. This is why tack welding and clamping project pieces is critical to successful welding. It is also important to match the welding process to the base metal thickness. For example, shielded metal arc welding is generally not used on materials less than 1/8" thick. The process is too hot and too difficult to control on thin material. On the other hand, gas metal arc welding works well on very thin sheet metal, if you are able to adjust the machine to a low enough voltage.

Shielded metal arc welding

Gas metal arc welding

Protecting the molten puddle from oxygen is also an important part of welding. Oxygen makes steel rust and causes corrosion in other metals. The exclusion of oxygen from the weld when it is in the molten state makes a stronger weld. This is accomplished in a variety of ways. A properly adjusted oxyacetylene flame burns off the ambient oxygen in a small zone around the weld puddle. Gas metal arc and gas tungsten arc welding bathe the weld in an inert gas from a pressurized cylinder. These inert gases keep oxygen away from the molten puddle. Flux cored arc welding and shielded metal arc welding use fluxes in or on the welding filler metal. When these fluxes burn, they produce shielding gases and slag, both of which protect the weld area until it has cooled.

Gas tungsten arc welding

Plasma cutting

Welding well is difficult and takes years to master, but it is possible to make many useful and decorative items with basic knowledge and a little practice. If you wish to move beyond the decorative projects outlined in this book, it is a good idea to talk with a welder and have him or her evaluate some of your welds. Remember, the safety of others is involved when you choose to make a utility trailer or spiral staircase. Take the time and make the effort to ensure that any structural project you make is safe.

This book is intended as a reference for people who have had some exposure to welding and need reminders about what steps to follow and precautions to take. It is not intended to teach welding to someone who has never handled welding equipment. Many community colleges, technical schools, and art centers offer welding classes. Such classes are an ideal way to learn the basics of welding, proper techniques for each process, and welding safety.

Oxyacetylene cutting

Welding can be a dangerous activity. Possibilities exist for getting cut, burned, electrocuted, and causing fires or explosions. Preparations for welding—grinding, burnishing, and sawing—are also dangerous. That said, it is absolutely possible, with a little care and diligence, to weld for years and never suffer more than a burnt thumb from being too eager to examine a just-completed weld.

It is very important to follow manufacturer’s specific instructions and recommendations for equipment and product use and to follow general welding safety rules. Whether you are welding in a dedicated welding shop or have set up your own shop at home, you need to be aware of a number of specific safety concerns.

Welding safety includes protecting yourself with protective gear, following manufacturer’s instructions, and being aware of the surroundings in which you are welding.

Fumes. Welding produces hazardous smoke and fumes. It is always important to keep your face out of the weld plume. Welding indoors requires either a ventilation fan, exhaust hood, or fume extractor. Wear an OSHA approved N99 particle mask or a respirator. If you are pregnant or plan to become pregnant, a respirator is a necessity.

Burns. Hot sparks and flying slag can cause burns. Protect your hands, head, and body with natural fibers—leather, wool, or cotton. Manufactured fibers such as nylon and polyester melt when ignited, which causes serious burns. Wear leather slip-on boots, and make sure your pant legs fall over the top of your footwear. Cuffed pants and pants with frayed edges are fire hazards. Also, welding sparks will find tiny holes, so don’t wear holey jeans. Wear a welding cap and tie back long hair and keep it tucked under your shirt or cap.

Arc burn. Welding arcs produce ultraviolet and infrared light. Both of these can damage your eyes permanently, burn your skin, and potentially lead to skin cancer. A welding helmet with a filter lens protects your eyes and face, while long sleeve shirts and long pants protect your skin. Remember, you are also responsible for protecting the vision of curious neighbors, passersby, and pets. Use welding screens and have an extra helmet on hand for observers.

Fire. The area you’re working in should be cleared of any flammable items such as lumber, rags, dropcloths, cigarette lighters, and matches. Absolutely do not weld or grind metal in a sawdust-filled shop. Sparks from welding and grinding can ignite airborne dust or fumes, or travel across the floor and come to rest against flammable materials. A fire extinguisher rated ABC is a must—mount it next to a first aid kit so you know where both are. Check your welding area one half hour after welding to make sure no sparks have found a place to smolder.

Explosion. Even non-flammable gases such as carbon dioxide are stored in cylinders at such high pressure that they can easily become dangerous missiles. Keep the cylinder’s protective cap on if regulators are not installed, and keep cylinders chained or strapped at all times. Cylinders should never be used as rollers or supports, and cylinders and protective caps should never be welded on. Shut acetylene and oxygen cylinder valves if you’re away for more than 10 minutes. Cylinders must be transported right side up and chained, even if empty.

Another explosion hazard is concrete. Because of the amount of water contained in concrete, it can become a steam bomb if welded upon. Tack welding on concrete is acceptable, but using a concrete surface to back your welds is not. Use fire bricks, which have been cured to have very low water content. Never weld or cut on any closed container, tank, or cylinder. Even if it has been empty for years, it might have enough residual material to release toxic fumes or explode. Always bring tanks of any sort to a tank welding specialist for repair.

Other hazards include noise from grinding, sawing, sanding, and plasma cutting; laceration from sharp metal edges; electrocution during arc welding; and asphyxiation from inert shielding gases. Carefully read all manufacturers’ instructions before starting any welding process.

Welding safety equipment includes: A. safety glasses, B. particle mask, C. low-profile respirator, D. leather slip-on boots, E. fire-retardant jacket, F. fire-retardant jacket with leather sleeves, G. welding cap, H. leather cape with apron, I. leather gloves with gauntlets, J. heavy-duty welding gloves, K. welding helmet with auto-darkening lens, L. welding helmet with flip-up lens, M. full-face #5 filter, N. full-face clear protective shield.

If you plan to weld on a regular basis, it makes sense to set up a welding shop. The primary concern with welding is containing the hot sparks or slag and the flammable elements while exhausting dangerous fumes. It is possible to weld outside, but not all processes allow that. Gas metal and gas tungsten arc welding require that the surrounding air be still so the shielding gas is not disturbed. All the arc processes must be done in dry conditions to prevent electrical shock. Cold metals do not respond as well as metals at 70° F and may not be weldable using certain processes. A heated garage or outbuilding is best suited for a welding shop. A basement is not suitable due to the dangers of fire and compressed gases next to living spaces. Additionally, your homeowner’s insurance may not cover a welding shop if it is inside your living area as opposed to in a detached garage or shop building.

Shop space with a concrete floor and cement block walls is ideal for welding. Good ventilation is also important.

It is important to remember that tiny sparks and pieces of hot slag may scatter up to 30 or 40 feet from the source. If they come to rest on flammable materials, they may smolder, and given the right conditions, can ignite the material. Always check your welding area one half hour after you have completed welding to make certain no sparks are smoldering. A wooden table covered with metal is not a good work surface, as the transferred heat may cause the wood to smolder. Any wooden jigs or clamping devices should be doused with water to extinguish smoldering embers or stored outside after use.

Power tools such as the reciprocating saw, angle grinder, portable band saw, and chop saw are useful when cutting and fitting metal parts to be welded. A drill press and metal cutting band saw are also useful tools for welding.

Specific metal working tools, including metal brakes and metal benders, are available for all sizes of metal. These can range from inexpensive sheet metal tools, such as the scroll bender shown on page 108, to expensive hydraulic tools.

Power tools for a welding shop (above photo) include: A. reciprocating saw, B. chop saw, C. portable band saw, D. angle grinder.

Standard tools for a welding shop include: A. magnetic clamp, B. center punch, C. metal file, D. C-clamp, E. corner clamp, F. tape measure, G. cold chisel, H. carpenter’s square, I. combination square, J. ball peen hammer, K. clamping pliers, L. magnetic level, M. hacksaw.

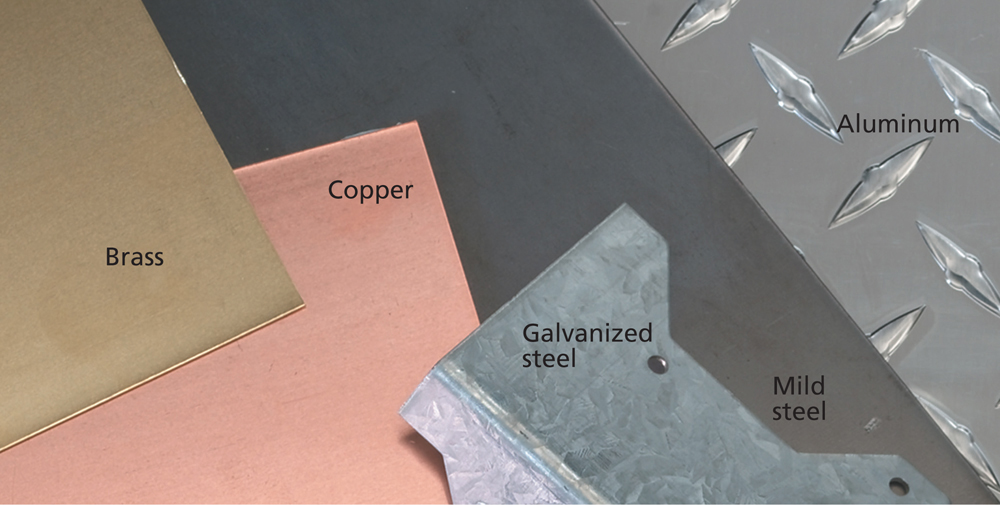

Different metals have different characteristics that affect their ability to be welded or cut with any of the processes described in this book. In general, only metals of the same type are welded together because welding involves melting the base metal parts and adding melted filler metal. In order to accomplish this, the parts and filler must have the same melting temperature and characteristics. Dissimilar metals can be joined by brazing and braze welding because these processes do not actually melt the base metal.

Metals are divided into the categories of ferrous and non-ferrous. Ferrous metals contain iron and will generally be attracted to a magnet. Cast iron, forged steel, mild steel, and stainless steel all contain iron, along with varying amounts of carbon and other alloying elements.

Mild steel, which has a low carbon content, is the most commonly used type of steel and the easiest with which to work. Mild steel can be welded with all the processes covered in this book and can be cut with either oxyfuel or plasma cutting. It makes up most of the metal items you commonly use, make, or repair, such as automobile bodies, bicycles, railings, patio furniture, file cabinets, and shelving. Adding more carbon to steel makes it harder, more brittle, and more difficult to cut and weld. High carbon steel is called tool steel and is used to make drill bits and other metal cutting tools.

Other elements are added to steel to make a variety of alloys, such as chrome moly steel and stainless steel. These additions may make the steel non-magnetic. Because stainless steel does not oxidize (rust) easily, it is difficult to cut with oxyfuel. When welding steel alloys, the filler material must be matched to the alloy to get a high-quality weld.

In addition to alloying, many metals are heat-treated to improve characteristics such as hardness. Because welding and cutting would reheat these metals and destroy those characteristics, heat-treating is an important factor to consider. Many vehicle chassis parts, including motorcycles and bicycles, are made of heat-treated metals.

Aluminum is a widely used non-ferrous metal because of its light weight and corrosion resistance. Like steel, it is available in many alloys and is often heat treated. Aluminum is used for engine parts, boats, bicycles, furniture, and kitchenware. Various characteristics make aluminum difficult to weld successfully—it does not change color when it melts, it conducts heat rapidly, and it immediately develops an oxidized layer.

Mild steel (and most other metals) come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and thicknesses. Metal thickness may be given as a fraction of an inch, a decimal, or a gauge (see following chart).

Rectangular tube (A) and square tube (B) are used for structural framing, trailers, and furniture. Dimensions for rectangular and square tubing are given as width × height × wall thickness × length.

Rail cap (C) is used for making handrails. Rail cap dimensions are the overall width and the widths of the channels on the underside.

Channel (D) is often used for making handrails. Very large channel is used for truck bodies. The legs, or flanges, make it stronger than flat bars. Dimensions for channel are given as flange thickness × flange height × channel (outside) height × length.

Round tube (E) is not the same as pipe. Round tube is used for structures, and pipe is used for carrying liquids or gases. Dimensions for round tube are given as outside diameter (O.D.) × wall thickness × length. Pipe dimensions are nominal, that is, in name only. They are given as nominal inside diameter (I.D.) × length.

T-bar (F) dimensions are given as width × height × thickness of flanges × length.

Angle or angle iron (G) has many structural and decorative uses. Dimensions for angle iron are flange thickness × flange width × flange height × length.

Square bar (H), round bar (I), and hexagonal or hex bar (J) dimensions are given as width or outside diameter × length.

Flat bar or strap (not pictured) is available in many sizes. Dimensions are given as thickness × width × length.

Sheet metal (not pictured) is 3/16" or less in thickness and is often referred to by gauge. Plate metal is more than 3/16" thick and is referred to by fractions or inches.

Finding a metal supplier can be a challenging task. The materials that are readily available may not be the sizes and shapes needed for a project and may be expensive. Metal dealerships may not be friendly to small accounts. Because steel is so heavy, Internet or catalog shopping carries prohibitive shipping costs. With some searching, however, most necessary materials can be found.

Metal is generally priced by weight, unless you are purchasing it at a retail store. The price for small pieces of mild steel at a home center or hardware store work out to be as much as $2 to $3 per pound. The price per pound for small orders at a steel dealership may be in the range of 50 cents. Large orders or repeat orders may be priced as low as 30 cents per pound. Many metal suppliers have an odds and ends bin or rack where pieces may be as low as 10 cents per pound. Specialty metals such as stainless steel and aluminum start at $2 to $3 per pound.

Smaller sizes and shapes of mild steel and aluminum are available at home improvement and hardware stores in three-, four-, and six-foot lengths. Welding supply stores often have a selection of ten- and twelve-foot lengths of the commonly used sizes. Steel dealers have most common sizes in stock and will order other sizes for you. Most mild steel shapes and sizes come in twenty-foot lengths, and many steel dealers will make one free courtesy cut per piece. You might want to have the metal delivered, depending on the amount of material you are purchasing. You can order metal through catalogs or the Internet, but remember that shipping is expensive.

Some steel dealers are distributors for decorative metal products, but many specialty items such as wrought iron railing materials, decorative items, and weldable hardware are only available by catalog. A number of catalog supply houses sell to the public and have varied selections and reasonable prices. (See Resources, page 140.)

Sheet metal is available as pierced or expanded. Wall plates, hooks, rings, balls, bushings, candle cups, drip plates, and stamped or cast items are available in a wide variety of shapes, sizes, and metals.

A successful weld begins with a well-prepared piece of metal. The cleaner the pieces to be welded, the better the weld quality and appearance. When working with mild steel, it is possible to clean batches of parts ahead of time. When working with aluminum, parts need to be cleaned immediately before welding due to aluminum’s nearly instant formation of a protective layer of oxidation. Mild steel is usually covered with mill scale and, often, oil or grease. Round and square tubes are usually thickly coated with oil, which helps in the manufacturing process. This oil can be removed with denatured alcohol, acetone, or a commercial degreaser.

Cleaning the mill scale off mild steel is an important step. A bench mounted power wire brush works well on small pieces. Wire brushing the entire project prior to finishing is critical for good paint adhesion.

After the oil has been cleaned off, the mill scale can be removed by wire brushing manually or with a bench-mounted or hand-held power wire brush, with sandpaper or sanding screens, or with an angle or bench grinder. Aluminum and stainless steel need to be brushed with stainless steel brushes that are dedicated to cleaning only that metal. Small particles of mild steel will contaminate aluminum and stainless steel welds.

Though most commercially available metal items—patio furniture, indoor furniture, and garden accessories—have rough welds and spatter still present, it is nice to grind these down on your projects. An angle grinder is good for flat area welds, and a small rotary grinding tool can get into nooks and crannies. You’ll be pleased with the results of a nicely ground, good weld because it looks like a solid piece of metal. Wire brushing, sanding, or sandblasting the entire piece will further prepare it for finishing.

Painting metal projects is best accomplished by spraying, not brushing. You will need to thoroughly clean all oil, dirt, slag, and spatter from the project because even advanced rusty metal primers will not to stick to dirty, oily areas. Metal spray paints are available in various finishes and a huge array of colors.

Powder coating and brass plating are other, more expensive, finish options. Various antiquing and rusting finishes are available as well, or you can let the piece slowly rust on its own if you prefer this look.

An angle grinder works well for beveling edges on thick material. Grinding down welds gives projects a finished look.

There are a number of ways to bend and shape mild steel. Bending tools for creating right angle bends are called metal brakes. Rollers create circles, punches make holes, and shearers make cuts. You can purchase simple hand-powered metalworking tools, though they can be costly—the higher the quality or larger the capacity, the higher the price. (See page 108 for a photo of a scroll bender.) Powerful hydraulic metal shaping tools made for commercial use can cost thousands of dollars.

Simple bending jigs can be made using any round, rigid, strong form, such as pipe and salvaged flywheels, pulley wheels, or wheel rims. Using these jigs, it is fairly easy to bend round rod up to 1/4" in diameter and flat bars up to 1/8" thick into complex shapes. Rebar up to 3/8" can be bent into large curves by clamping it into a bench vise. Tubing can be bent using an electrical conduit bender. Thick material such as rail cap can be heated and bent.

You can bend materials more easily if you have a long end to apply pressure to, so you may want to cut pieces to length after bending. Whenever you shape metal into sharp angles, take into account the length needed for the radius of the bend. Also, cold-formed metal will spring back somewhat, so it may take trial and error to find what size jig will make the size bend you desire.

Use a sturdy hacksaw, jig saw, or reciprocating saw with bi-metal blades to saw metal. A miter box will help you make accurate cuts. A metal band saw, either portable or bench mounted, is handy if you will be making many projects that require numerous cuts. You can drill metal with a power drill or drill press, using metal cutting bits and oiling the bit often to prevent overheating. Large holes or holes in very thick material might be made more easily with an oxyfuel cutter or plasma cutter. An angle grinder or bench grinder can be used to create tapers or to correct miscut items to get better fit ups for welding.

Bending jigs can be made from any rigid circular item. An engine fly-wheel, toilet flange, and various pipe sizes are shown here.

Use a vise style pliers to hold the metal to the jig. Wrap the metal around the jig in a smooth motion.

Use a slower drill speed and a metal cutting bit for metal drilling. Frequent application of oil prevents overheating.

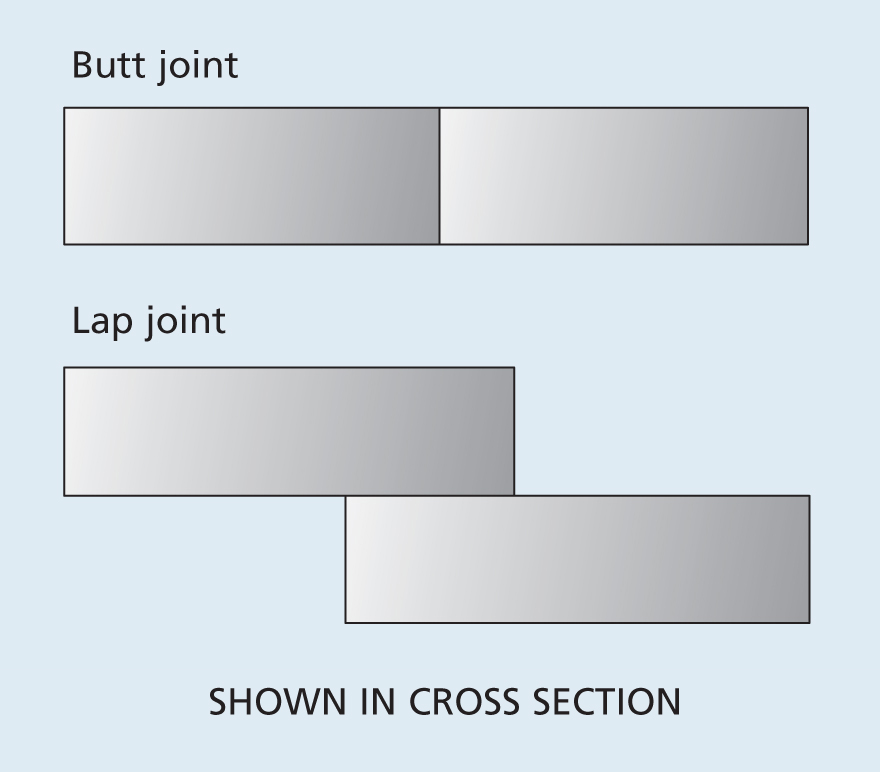

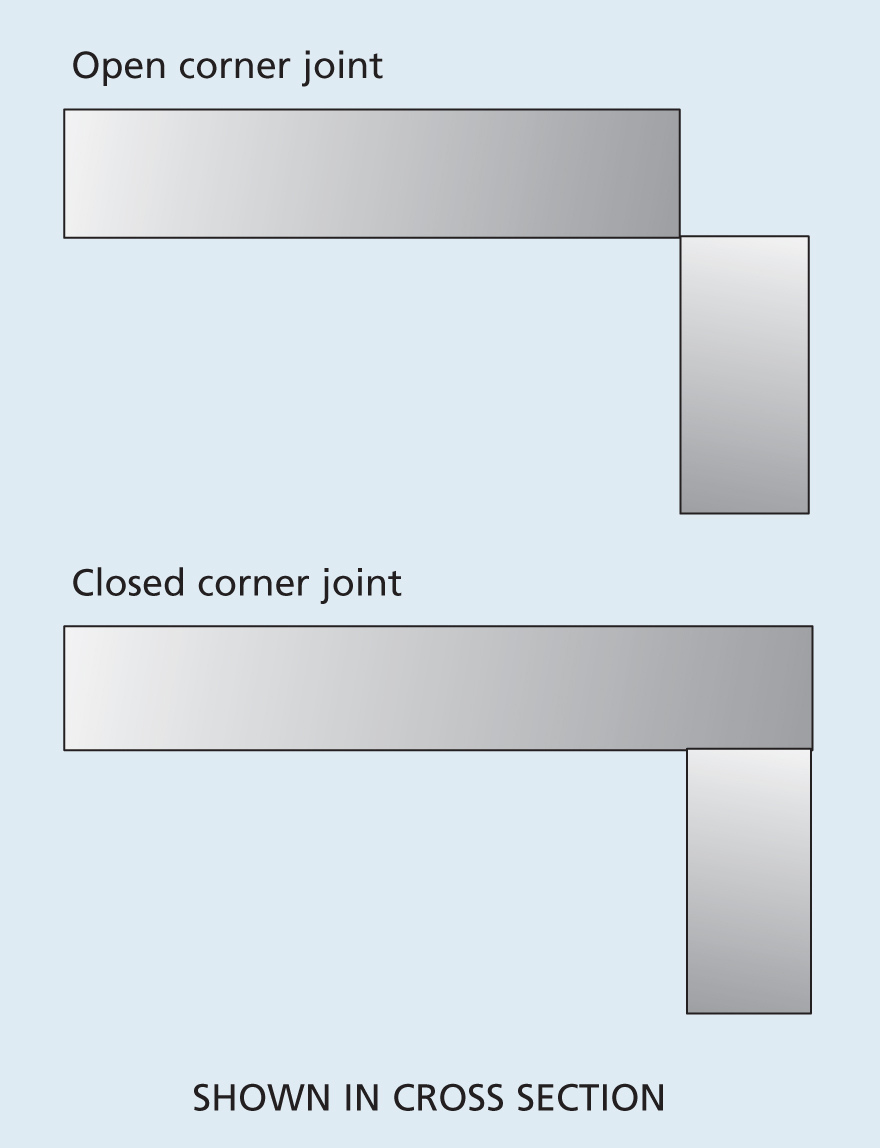

The basic joints in welding are the butt joint, lap joint, corner joint, T-joint, edge joint, and saddle joint.

The butt joint is two pieces in the same plane butted against each other. The gap between the pieces is determined by the thickness of the pieces. Whether or not the surfaces need to be ground down (beveled) is also determined by the plate thickness. The type of weld used for a butt joint is a groove weld. The butt joint is a weak joint and should be avoided if at all possible.

A lap joint is two pieces in the same plane overlapped. The type of weld used for a lap joint is called a fillet weld. The strongest lap joint has welds on both sides.

A corner joint is two pieces coming together to make a right angle at a corner. The joint can be open, partially open, or closed. An open corner takes a fillet weld, but other corner joints may take groove welds. For hobby welding on metal 3/16" and thinner, an open corner joint is stronger and allows more penetration. A closed corner joint may be weakened if the weld is ground.

A T-joint is two pieces placed together to make a right angle T shape. Again, it is welded with a fillet weld. A T-joint is stronger if both sides are welded.

The edge joint, or flange joint, as it is sometimes called, is predominantly used to join thin sheet metal components. The turned up edge lessens the heat distortion to the thin sheets. With the advent of cooler welding processes, the need for the edge joint has diminished.

The saddle joint, or fishmouth joint, is used to join structural tubing. The tubes may join at any angle, and more than two tubes may be part of the joint. A fillet weld is used, most often all the way around the joint.

Welding blueprints use specific symbols to denote weld types, locations, and other factors. The basic symbol consists of an arrow and a reference line with weld symbol. The weld symbol is placed above the reference line if the weld is located on the side opposite the arrow, and below the reference line for a weld located on the same side as the arrow. Weld symbols above and below the reference line indicate to weld both sides. A circle at the junction of the arrow line and reference line means to weld all around. Most hobby welders will not encounter these symbols.

The most common weld types used for home welding are the fillet and groove welds.

The fillet weld is roughly triangular in shape. It is made when welding most 90° angle joints. T-joints, open corner joints, lap joints, and saddle joints all take fillet welds.

The groove weld is made in a groove between pieces. The groove may be square grooved (straight sides), beveled (flat angled sides), or U shaped. The groove weld is used for butt joints, edge joints, and closed corner joints.

Once you begin welding, you will encounter numerous opportunities to repair items. When your friends and neighbors discover you can do repairs, even more challenges will come your way.

Performing welded repairs can be very tricky. It is important to assess your welding skills, the difficulty of the repair, and the intended use of the repaired item. Any structural or vehicle repairs, such as stairways, ladders, trailers, or truck chassis, need to meet the same safety standards as they did in their original condition.

The first step in considering a repair is determining why the item broke. If a weld was poorly executed, the repair might simply be to prepare the area and perform a good weld. If a piece has broken due to metal fatigue, simply “patching” over the crack will only cause more cracks outside the patched area. Cast iron and cast aluminum may have broken due to imperfections or inclusions in the casting, or they may have gone through rapid heating and cooling that caused cracking. Very often things break because they have been misused—which means your repair will likely be broken unless the behavior of the user changes.

All parts need to be carefully prepared before attempting a repair. Paint needs to be ground or sanded off and grease and oil need to be cleaned away. This cast iron part is being beveled to allow greater weld penetration.

The next step in a repair is determining what the base metal is. A magnet will be attracted to any metal with a certain concentration of iron in it, but stainless steel (which is sometimes non-magnetic), mild steel, and cast iron require very different welding techniques. Aluminum is non-magnetic and is discernable from stainless steel by its light weight—but which alloy is it? In the case of aluminum, some alloys are not weldable. Unfortunately, many manufactured metal items are made of alloys and may have been heat treated. Without access to the manufacturer’s specifications, it might be impossible to determine what the base metal composition is. It is important to understand the effects of welding on these materials before attempting a welded repair.

Once you have determined the feasibility of a repair on a particular piece, the piece must be prepared carefully. All rust, paint, and finishes must be removed from the area of the weld, and, if you are arc welding, from an area for the work clamp. Grease and oil must be cleaned off. If the break is on a weld joint, the old weld bead needs to be ground down.

Mild steel is the easiest material to repair. Simply prepare the material as for any other weld, and weld using any of the welding processes.

Cast iron and cast aluminum need to be preheated before welding to prevent cracking due to temperature fluctuations. If the piece is small enough, you can put it in the oven and heat it to 400 to 500° F. Otherwise, use an oxyacetylene or propane rosebud tip. Temperature crayons, which melt at specific temperatures, are available for marking metal to be preheated. Cast iron can be brazed if the fit between the broken parts is good, or it can be braze welded or welded with shielded metal arc. Specific electrodes for cast iron are available. Cast aluminum can be brazed, braze welded, or welded with gas tungsten or gas metal arc welding. Allow cast parts to cool slowly after welding.

Some aluminum is not weldable. If the piece to be repaired has been welded, you can perform a welded repair. If you can determine the composition of aluminum parts, match the electrode or filler rod to that. Some filler rods and electrodes are multipurpose and can be used on more than one alloy. Gas tungsten arc welding is the best choice for aluminum, but it can also be welded with gas metal arc, or it can be brazed.

Stainless steel comes in numerous alloys, and it is important to match the filler material to the base metal. Do not clean stainless steel with a steel wire brush, as the mild steel wires may contaminate the stainless steel. Stainless steel is best repaired with gas tungsten arc welding, although it can be brazed as well.

If you are unsure of any aspect of a potential repair, consult with your welding supply dealer or an expert welder.

Remove the paint and finish from the weld area. If you are arc welding, also remove the paint from an area close to the weld for attaching the work clamp.

Cast iron can be braze welded as shown here, or shielded metal arc welded with cast iron electrodes. Either way, the metal needs to be preheated to 450° F before being welded.