All plant foods contain carbs to a greater or lesser extent – fruits, vegetables, legumes, grains and some nuts – as do milk and yoghurt, but not most cheeses (the whey is drained away so it is just protein and fat). Exceptions include cottage cheese and ricotta.

Carbs, or carbohydrates to give them their full name, are one of four major molecules in our foods, and like two of the others – protein and fat – they provide us with energy (calories or kilojoules). The fourth major molecule is water. Most foods are a mix, some have two or three of them, others have all four. All carbs have some water, but some (grains, legumes, seeds and nuts) also put protein and fats on the plate. And there’s more: good carbs serve up a swag of micronutrients, including vitamins B, C and E, and minerals including magnesium, potassium and calcium.

Sugars are carbs, as are starches, and the bonus indigestible dietary fibres and resistant starches that nourish the gut, feed our friendly gut bacteria and keep things moving along nicely on the inside are also carbs.

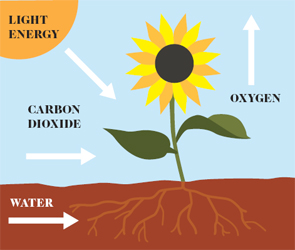

Where do carbs come from? All living things need food to survive. It’s the fuel that generates the energy to grow, thrive and reproduce. The most abundant source of energy on Planet Earth is the sun. When it comes to making the most of solar power – converting sunlight into energy – plants (and other organisms) have been doing it for about three billion years.

Think of green leaves as solar panels that gather sunlight then use it to convert carbon dioxide (absorbed from the air) and water (sucked up by roots) into the sugars and starches needed to grow roots, stems and leaves, and to produce flowers, fruits and seeds. They also use carbohydrates to make their cell wall materials (indigestible to us), including cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin, along with various gums and pectins. One way or another, green plants provide us with most of the energy that fuels our lives, from the fossil fuels formed millions of years ago to the foods we grow in our gardens and on our farms. And there’s more: there’s the oxygen they release into the atmosphere so we can all breathe easy.

HOW PLANTS FUEL OUR LIVES

So how do we use a plant’s energy? When we eat fruit or tubers, our bodies convert their sugars and starches into the glucose that provides energy to power our body, our brain, our blood cells, our reproductive organs and our muscles during vigorous exercise day in and day out.

WHAT CARBS DO

Good carbs are multi-talented molecules that play a number of key roles in our body. First and foremost, our brains and nervous system, red blood cells, kidneys and our exercising muscles much prefer to use them as their energy source. But they also give our cells structure, are part of our genes (the sugar ribose is part of our DNA) and play a part in the function of some proteins. And on top of all this they give us great enjoyment with the taste, flavour, aroma, texture and colour they bring to our meals with family and friends.

Carbohydrates are made up of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen, so you can see where the name comes from. For example, the chemical formula for glucose is C6H12O6, which stands for six carbon atoms and six water molecules (H2O = one water molecule; six water molecules = H2O × 6). In this book we’ve chosen to refer to them as carbs most of the time.

There are many kinds of carbohydrates. The four most common in our foods and drinks are sugars, oligosaccharides, starches and dietary fibres. Here’s a summary of what they are and what they do.

SUGARS

Sugars are the simplest form of carbohydrate. Again, there are many kinds. The six main sugars in our foods are either monosaccharides or disaccharides (saccharum is Latin for ‘sugar’) and they all end in ‘ose’.

Monosaccharides are single-sugar molecules (mono is Latin for one). The three most common ones in our foods are (in alphabetical order):

- fructose, which is found in fruits, honey, and agave and maple sap. It makes up around half of the carbs in a typical piece of fruit and is commonly called fruit sugar. It is about 50 per cent sweeter than glucose.

- galactose, which is found in milk, yoghurt and whey and is 20 per cent less sweet than glucose.

- glucose, which is found in fruits, grains, vegetables, and honey. Here’s what a glucose molecule looks like.

Disaccharides are two single-sugar molecules joined together (di is Latin for two). The three most common ones in our foods are (in alphabetical order):

- lactose, glucose plus galactose, which is found in milk. All mammal milk contains lactose, but human mother’s milk, which is part of a baby’s very special fuel mix, is the richest by far. Lactose is also added to foods during processing.

- maltose, glucose plus glucose, which is found in grains such as barley and in malt and malted foods and beverages. It is commonly added to foods as an ingredient.

- sucrose, glucose plus fructose, which occurs naturally in fruit, sugar cane (a grass) and sugar beets, the sap of maple and birch trees. It is the most common form of sugar added to foods and drinks in most parts of the world, with the exception of the United States, where high-fructose corn syrup is used because it’s cheaper for historical and political reasons we won’t go into here. Here’s what a sucrose molecule looks like:

OLIGOSACCHARIDES

Chains of 3–9 glucose molecules joined together are called oligosaccharides, which literally means ‘a few sugars’ (oligo is Latin for ‘a few’). They are only slightly sweet. The main ones found in foods or increasingly used in food processing are as follows:

- fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), which are short chains of fructose molecules found naturally in fruits and vegetables such as asparagus, bananas, chicory root, garlic, Jerusalem artichokes, leeks, legumes, onions and wheat; and in wholegrain foods, especially rye. They are actually a form of dietary fibre and they play a role as prebiotics, the non-digestible components of plant foods that promote good gut health by feeding the friendly bacteria (probiotics) in the large intestine (bowel). Inulin is one you will increasingly see on food labels as manufacturers add it to products to boost fibre content and reduce regular added sugars. While it may be good for digestive health for some, it can be digestively challenging for those with irritable bowel syndrome.

- maltodextrins (modified food starches), which are mostly man-made carbs manufactured by the partial hydrolysis (using water to break down large molecular chains) of starch (from corn, potato, rice, wheat or tapioca) and they may or may not be gluten free depending on the starch source. They are widely used by the food industry as moderately sweet or even flavourless food additives to provide bulk and texture in processed foods. Food manufacturers are increasingly replacing added regular sugars in processed foods with maltodextrins (plus a non-nutritive sweetener if sweetness is required) responding to consumer (and governmental) demand for no added sugars. But they’re not better for our health. They contribute to tooth decay, provide empty calories and raise our blood glucose levels more rapidly than regular sugar. (The GI of table sugar or sucrose is 65; maltodextrin’s GI is estimated to be 75.) Here’s what a maltodextrin molecule looks like:

ADDED AND FREE SUGARS

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that we consume no more than 10 per cent of our energy from what it calls free sugars. This may reduce our risk of developing tooth decay, and also help us limit our intake of excess calories. The sugars WHO is talking about are added sugars from table sugar, honey, syrups (glucose syrups such as rice syrup), fruit juices and fruit juice concentrates. What does 10 per cent free sugars look like? For the average adult consuming 2070 calories (8,700 kilojoules) a day, it’s about 13 level teaspoons or 54 grams of free sugars.

STARCHES

Starches are part of the large group of polysaccharides (many sugars) – long chains of glucose molecules. They are found naturally in a wide range of foods including grains, legumes, potatoes and other starchy vegetables, nuts and seeds. Milled to make a flour or meal, we use them in our cooking to make breads and sauces. There are two kinds: amylose and amylopectin.

- Amylose is a straight chain of glucose molecules that tend to line up in rows like a string of beads and form tight, compact clumps that are harder for our bodies to gelatinise (see box, here) and digest.

- Amylopectin is a string of glucose molecules with lots of bushy-looking branching points, such as you see in some types of seaweed or a tree. Amylopectin molecules are larger and more open, and the starch tends to be easier for our bodies to gelatinise and digest.

WHAT IS DEXTROSE?

Dextrose is just another term for glucose. It comes from ‘dextrorotatory glucose’, because a solution of glucose in water rotates the plane of polarised light to the right (dextro is Latin for ‘right’). If you see dextrose in an ingredients list of processed foods and drinks, it probably means that the added glucose was produced from cornstarch. Without going into the chemistry of how they do that here, the process is similar to the way our body converts starches to glucose during digestion. Levulose is another term for fructose and means ‘left turning’ (laevus is Latin for ‘left’), because a solution of fructose in water rotates the plane of polarised light to the left.

WHAT IS GELATINISATION?

Have you ever tried to eat raw rice or dried beans or raw potato? Not a good experience. That’s because the starch in these foods is stored in hard, compact ‘granules’ that make it virtually impossible for our starch-digesting enzymes to attack and digest. And that’s why we cook them. It makes the difference called ‘gelatinisation’, that is, it softens them up.

Let’s take rice. The absorption method tells us to throw 1 cup of rice into the pot with 1½ cups of water and bring to the boil. Reduce the heat and simmer, covered, for 20 minutes or until the water has been absorbed. Remove from the heat, keep covered and set aside for 5 minutes.

So what happens in the cooking pot? The starch granules absorb the water, swell up and some burst, freeing thousands of starch molecules. We now have fluffy rice and a food we have no difficulty tucking into and digesting, because our highly specialised starch-digesting enzymes have a lot more accessible surface area to attack.

DIETARY FIBRE

This is what we refer to as the ‘BTU’ (bowel tune-up) carb. Most dietary fibres are large molecules with many different mono-saccharides that come mostly (but not exclusively) from plants and provide much of the bulk in our stools. When we eat fibre-rich foods like prunes, the fibres are not broken down and metabolised during digestion; instead, they go through our stomach and small intestine into our large intestine, where hordes of good bacteria waiting for a feed greet them enthusiastically. There are numerous ways to group dietary fibres; the most common one is whether or not they’re soluble in water.

- Water-soluble fibres (usually just called soluble fibre) include gums such as agar, fructo-oligosaccharides such as inulin, mucilages such as psyllium, and pectins. They are found in fruits, vegetables, legumes and some grains (oats and barley). They may help reduce blood cholesterol levels and keep blood glucose levels on a more even keel, but how successful this will be will depend in part on the degree of food processing and how much you eat.

- Water-insoluble fibres (usually just called insoluble fibre or roughage) include cellulose, hemicellulose and lignins. They are mostly found in vegetables, wheat and other whole grains, nuts and seeds. They primarily help us move our bowels (laxation is the technical term), and in this way they can help reduce the risk of constipation.

HOW WE DIGEST, METABOLISE AND ABSORB CARBS

Most of the carbs in the foods we eat are digested in the stomach and small intestine, absorbed into the bloodstream and, one way or another, converted into glucose. For most carbs, the process is relatively simple.

As we have explained, starches and maltodextrins are simply chains of glucose joined together by chemical bonds. During digestion, small proteins called amylases in our saliva and intestinal digestive juices (secreted by the pancreas) snip the bonds so we wind up with pure glucose in the small intestine, which is then absorbed into the bloodstream.

WHAT IS GLYCOGEN?

Glycogen is a kind of starch that our bodies make and store as backup in the liver and muscles (we can store 1500–1900 calories/6000–8000 kilojoules worth). It comes from the carbs we consume and provides energy we can draw on when our carb stores run low with fasting or intense exercise. When carb stores run low, our bodies convert the glycogen back into glucose to power our muscles and brains.

Specific enzymes in our small intestine – lactase, maltase and sucrase – break the disaccharides lactose, maltose and sucrose down into their constituent monosaccharide molecules (glucose, fructose and galactose), which are then absorbed into the bloodstream.

The glucose molecules can be absorbed directly into the cells of most of the body’s tissues and organs, where they usually end up as pyruvate and adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is our body’s main energy currency. Normally, pyruvate is also converted to ATP, producing more energy. The galactose and fructose molecules, however, need to go to the liver for further processing.

In the liver, fructose is rapidly removed from the bloodstream, phosphate is added via a catalysing enzyme, and the resulting phosphorylated fructose enters what is known as the glycolytic pathway, where through a series of chemical reactions, it usually ends up as pyruvate and ATP. Similarly, galactose is extracted from the blood and converted to glucose in the liver, and then converted to pyruvate and ATP, just like glucose.

This is when the blood glucose story begins. When the glucose molecules enter the bloodstream, our blood glucose (sometimes called blood sugar) levels (BGLs) rise. This is the signal for the pancreas to release the hormone insulin, which tells most of the body’s organs and tissues to get to work and absorb the glucose from the blood to fuel our brain, cells, tissues and muscles. Insulin also stops our liver from releasing glucose from its glycogen stores.

WHY OUR BLOOD GLUCOSE LEVELS MATTER

Our body converts the sugars and starches to glucose at very different rates. Think of it as the highs and lows of carb digestion. And this is where the glycemic index (GI) can help us make better food choices. The GI is particularly useful for people who need to manage their BGLs. It is just a dietary tool providing a numerical ranking (from 1 to 100) that gives us an idea as to how quickly our bodies will digest particular carb foods and how fast and high our BGL is then likely to rise. Think of it as a ‘carbo speedo’.

WHAT IS RESISTANT STARCH?

Many scientists categorise resistant starch as another form of dietary fibre these days because of what it does. It’s actually starch that resists digestion and absorption in the small intestine and zips through to the large intestine largely intact to be fermented into short-chain fatty acids, like acetate, propionate and butyrate by those good gut bacteria we have down there. Current research suggests it may well be as important as fibre in helping reduce the risk of colorectal cancer, so it has a lot of fans.

It’s found naturally in unprocessed cereals and wholegrains, firm (unripe) bananas, beans and lentils. But you can create it in your own kitchen when you make potato, rice or pasta salad – starchy foods that you cook and then cool.

- High GI: 70 and over

- Medium or moderate GI: 56–69

- Low GI: 55 and under

Why does it matter how high our BGL goes? As with blood pressure, there’s a healthy range and a risky range. Having BGLs in the normal range over the day is good for our body because it also will lower our day-long insulin levels. Having high BGLs from eating too many high-GI foods can put pressure on our health, because it means our pancreas has to work extra hard producing more insulin to move the glucose into the cells, where it provides energy for the body and brain. It’s never a good idea to overwork or overstress body parts. They can wear out or stop functioning properly. We can’t easily replace our pancreas.

DOES FIBRE LOWER THE GI?

Not necessarily. It depends on amounts, size and processing.

- Soluble fibre may lower the GI of some foods, but they need to contain appreciable amounts, and the size of the fibre molecules needs to be large enough to have an effect.

- Insoluble fibre can help slow the rate of carbohydrate digestion or absorption if it is largely intact. However, highly processed added fibres usually do not have the same effect.

There are many benefits to switching to low GI good carbs that will trickle the glucose into the bloodstream. They can help us cut cravings and feel fuller for longer, stay in shape better by minimising body fat and maximising muscle mass, and decrease the risk of some chronic conditions, such as type 2 diabetes and heart disease. Throughout this book we provide the GI values of the good carbs we like to cook with and serve to family and friends.

Research around the world over the past 35 plus years shows that switching to eating mainly low GI carbs throughout the day that will trickle glucose into our bloodstream lowers our day-long BGLs and insulin levels helping us:

- manage our appetite because we will feel fuller for longer

- minimise our body fat

- maximise our muscle mass

- decrease our risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

How is the glycemic index of a food measured? A small group (10 or more) of healthy people follow an internationally standardised procedure. Each person is typically given a 50 gram portion of available carbohydrate (sugars, maltodextrins and starches, but not dietary fibre), then their blood glucose levels are measured every 15–30 minutes for the next 2 hours. This process is followed for both a standard food (glucose or white bread) and a test food, on two separate days. The BGLs from both days are then plotted on a graph, the dots are joined to create a blood glucose curve, and the area under the blood glucose curve is calculated using computer software. The result for the test food is divided by the result for pure glucose to derive the glycemic index value, which is simply a percentage.

Speed of digestion is only one part of the story. Quantity counts. How high our blood glucose actually rises and how long it remains high after we eat a meal containing carbs depends on both the amount of carbs in a food or drink and its GI. Some fruits, like melons for example, have a high GI but not many carbs as they are mostly water, so their glycemic impact will be negligible unless you massively overdo it.

Researchers from Harvard University and the University of Toronto came up with a term to describe this ‘speed–quantity’ combo: glycemic load (GL). It is calculated by multiplying the GI of a food by the available carbohydrate content (carbohydrates minus fibre) in the serving (expressed in grams), divided by 100 (because GI is a percentage). (GL = GI/100 × available carbs per serving.)

For example, a typical medium-size apple has a GI of 38 and contains 15 grams of available carbohydrate. Its GL therefore is 38 × 15 ÷ 100 = 6. If you are hungry and the apples are particularly crispy, juicy and delicious, and you eat two, the overall GL of this snack is 12.

What does this all mean for our health and wellbeing? One unit of GL is equivalent to 1 gram of pure glucose. So the higher the GL of a food or meal, the more insulin your pancreas needs to produce to drive the glucose into your cells. When we are young, our pancreas can produce enough insulin to cover the requirements of high GL foods and meals, but as we get older, it may no longer be able to cope with higher insulin requirements. This is when type 2 diabetes and other lifestyle-related diseases can start to develop.

IT’S NOT JUST CARBS THAT AFFECT OUR BLOOD GLUCOSE

Carbs have the most profound effect on our BGLs. But protein and fat may also increase our BGLs due respectively to increased glucose output from the liver and acute insulin resistance. They also affect insulin responses, and the effect in some scenarios is comparable to that of carbs.

Insulin is an anabolic hormone – it stimulates glucose and amino acid (building blocks of proteins) uptake by our body’s cells, and stimulates glycogen and fat synthesis within them. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many recent weight-reduction diets home in on insulin for its weight-promoting effects, and as carbohydrate is one of the most potent stimulators of insulin secretion, it has been singled out as the primary cause of weight gain in the modern era.

Carbs in foods and drinks are potent stimulators of insulin release, but they only explain around half (47 per cent) of the variation in our blood insulin levels. Foods high in protein and fat also increase our insulin requirements. Research to date shows that whey protein is the most potent insulin stimulator, followed by fish, beef, egg and chicken.

Fats may lower insulin requirements when we first consume them because they delay the rate at which foods are emptied from the stomach into the small intestine and absorbed into the blood. However, an increasing body of evidence suggests that they raise insulin requirements 3–5 hours after a meal, most likely due to increased insulin resistance.

So when you read the latest diet book singling out carbs as the dietary villain behind the global obesity and diabetes epidemics, advising you to quit them and replace them with protein and fats, remember that all three calorific macronutrients have an effect on our BGLs and blood insulin levels. As always, beware of the unintended consequences of fad diets in general, and the one-nutrient-at-a-time approach in particular.

PUTTING IT ALL ON THE PLATE

We burn a mix of three key fuels that we get from the foods we eat. Dietitians and nutritionists call these fuels ‘macronutrients’ because our bodies need lots of them. They provide us with energy (kilojoules or calories) and, in wholesome foods, they also come with vitamins and minerals.

- Carbohydrates (carbs) from fruit, vegetables, legumes, grains, some nuts and milk give us much more than energy, they provide us with the fibre, vitamins, minerals and the phytonutrients we need.

- Fats from nuts, seeds, oils, avocados, fish, meat, dairy foods and coconuts provide us with the fatty acids that are part of our cell membranes, and help us absorb the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K.

- Proteins from dairy foods, eggs, fish and other seafood, red meat, chicken and other poultry, legumes, nuts, seeds and grains are the body builders. They maintain our body tissues and, when wholesome, help us meet our needs for certain vitamins (especially B vitamins) and minerals (especially iron, zinc and calcium from dairy foods).

While alcohol does not meet all of the requirements to be a true macronutrient (e.g. growth and development) it is found in relatively large amounts in many beverages enjoyed by humans for many thousands of years, and is a source of energy that can be utilised by our bodies.

CALORIE COUNTDOWN

- 1 gram of carbohydrate (sugars and starches) contains 4 calories or 16.5 kilojoules

- 1 gram of protein contains 4 calories or 17 kilojoules

- 1 gram of fat contains 9 calories or 37 kilojoules

- 1 gram of alcohol contains 7 calories or 29 kilojoules

It’s often said that we run on fuel just as a car runs on petrol. The running part is right. But there are significant differences. Fuel storage is one. Cars have a set storage capacity: when the tank is full, it’s full. The excess runs over the rim and is wasted. We, on the other hand, seem to have unlimited capacity for storage, even if we constantly overfill the ‘tank’. We don’t waste the excess, we store it as fat. This would have been a handy feature in days of yore, as it would have provided a reserve of energy to call on in a poor season or when the hunters had a run of bad luck. But hunger isn’t an issue for most people in the developed world these days. Dealing with excess is our biggest challenge.

Our fuel mix changes at different stages of our lives, too. A growing baby has different needs from a toddler, teenager, sedentary adult, very active adult, an elderly person, or someone with a chronic condition such as diabetes.

BABY’S VERY SPECIAL FUEL

For the first 6 months of life, Mother’s milk provides the perfect mix of nutrients (carbs, fat, protein, vitamins and minerals) – and water – for our babies to grow and thrive. Mother Nature made it sweet, so it is very appealing to babies. They don’t like sour.

The sweetness comes from a special sugar called lactose found only in milk. Our human milk has the highest concentration of lactose of any mammal, almost double that of cow’s milk, coming in at some 7 grams of lactose per 100 millilitres (3½ fluid ounces), or little over 1/3 cup. Why so much? One reason is probably to satisfy our fast-growing, energy-hungry, glucose-demanding brain. Scans show that a baby’s brain reaches more than half adult size in the first 90 days of a baby’s life.

Mother’s milk also contains special carbs called oligosaccharides (see here), but think of them as prebiotics, foods that friendly bacteria in the large intestine chomp on to thrive. It’s thought that the special oligosaccharides in human milk may be one of the reasons why breastfed babies tend to have less gastrointestinal disease than bottle-fed babies.

WE CAN PICK OUR MIX

After infancy, we have considerable flexibility in our fuel mix options because we are omnivores. Our diet is not limited to ‘one size fits all’ because we evolved to be adaptable. That’s what made us successful in populating the planet and thriving in very different parts of the world.

While our fuel mix needs to include all three of the macronutrients, there are no strict rules about how much of each our bodies need, despite what some diet books proclaim.

You only have to look around the world to see that there are very different dietary patterns with very different fuel mixes associated with good health and long life. Traditional Mediterranean and Japanese diets, which are both linked with a long and healthy life, couldn’t be more different. The Mediterranean diet is relatively high in fats and tends to be rather moderate in carbs. The Japanese diet, like most Asian diets, is high in carbs and low in fats. What they have in common and what seems to matter most is that they are based on good, wholesome foods and ingredients – mostly plants.

MOTHER’S MILK FUEL MIX FOR BABIES

Per 100ml (3½ fl oz)

| ENERGY | |

| Kilojoules | 280 |

| Calories | 67 |

| MACRONUTRIENTS | |

| Carbohydrate (mostly lactose) | 7.0 g |

| Fat | 4.2 g |

| Protein | 1.3 g |

| MICRONUTRIENTS | |

| Calcium | 35 mg |

| Sodium | 15 mg |

| Phosphorus | 15 mg |

| Iron | 76 mg |

| Vitamin A | 60 mg |

| Vitamin C | 3.8 mg |

| Vitamin D | 0.01μg |

In what author and researcher Dan Buettner called ‘Blue Zones’, the story is the same. In these communities he reports that people don’t follow diets, cut out foods or go to the gym but are 10 times more likely than the rest of us to be living a healthy, active life until they are 100. How? They eat food, not too much, mostly plants; are active every day; get plenty of sleep; are not stressed out; and have strong social connections. He found that their diets are as noteworthy for their diversity as for what they share. In Loma Linda, California, they are vegans. In Costa Rica, their diet includes eggs, dairy and meat. In Ikaria, Greece, and Sardinia, Italy, they practise variations on the theme of the Mediterranean diet. In Okinawa, Japan, a traditional plant-based, rice-centric diet produces the same outstanding results.

On the home front, our tastes and our family background play a large part in what we eat and like to eat. In the end, the overall quality and quantity of the foods we consume is what really matters. That means building healthy eating habits and being a good role model for the next generation, who are watching us more carefully than we know.

Day to day and over the short term, we know that low-GI carbs are best for our blood glucose levels and sustained energy, and dietary fibre may help lower blood cholesterol levels and keep us regular. The evidence is stacking up showing much longer term benefits. Long-term observational studies including the Blue Zones studies provide compelling evidence that dietary patterns rich in low-GI carbs and dietary fibre reduce the risk of weight gain, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease and certain kinds of cancer, such as colorectal cancer.

And that’s why we wrote a book about cooking with good carbs. We wanted to share the news about the long-term health benefits of making them a part of your day and to give you some delicious ways to do so.

We also wanted to cut through the confusion and help you enjoy good food and good health, with good information to make good decisions about the foods you prepare and enjoy with family and friends. There’s no need to mortgage the house and rush out and stock up on celebrity superfoods such as teff, maca, sprouted grains and pepitas or even fill your fridge with pricy salmon and blueberries. Good wholesome foods you can afford and your family will enjoy will do the trick. After all, full tummies and clean plates is what it’s all about. That means shopping for:

- lean protein – dairy foods, eggs, fish and other seafood, red meat, poultry and legumes. These are the body builders. They maintain our body tissues and help us meet our needs for certain vitamins (especially B vitamins) and minerals (especially iron, zinc and calcium from dairy foods if you eat them).

- good fats – nuts, seeds, oils, avocados and coconuts. These provide us with the fatty acids that are part of our cell membranes and help us absorb the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K.

- good carbs – fruit, starchy vegetables, legumes (beans, peas and lentils), seeds, grains and milk or yoghurt that give us much more than energy. They provide us with the fibre, vitamins, minerals and phytonutrients we need.

WHAT ABOUT THE MICROBIOME?

Our microbiome is a collection of around 40 trillion bacteria (mostly), fungi and viruses that live both on the surface of our body and inside our gastrointestinal tract (from the mouth to the large intestine).

A typical adult’s microbiome weighs around 1 kilogram, equivalent to some of our essential organs. Believe it or not, there are about 10 times more bacteria in our microbiome than there are cells in our body, or put another way, 90 per cent of the cells in our bodies are microbial and only the remaining 10 per cent are human!

The composition of our microbiome is not static. It changes throughout the course of our lives, in sickness and health, and can be manipulated with antibiotics and transplants – and by the foods we eat – in a way our genes cannot. Manipulating our microbiome may hold the answers to the treatment of conditions that may not seem to have anything to do with bacteria, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. For example, preliminary research in humans is showing that the proportion of these microorganisms is different between overweight and slim people. However, it is not yet known whether it is the differences in the types of bacteria that cause people to gain weight or whether the differences are the result of people being overweight. Put simply, are they the cause or the effect? At this stage we just don’t know.

Just as you can cultivate healthy soil for your garden, there is growing evidence that you can help cultivate a healthier microbiome too. Eating live varieties of healthy bacteria can help to improve the balance of bacteria in your gut. For years the yoghurt industry has been extolling the virtues of yoghurt and fermented milk with claims that it contains Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei or bifidobacteria. These varieties are generally beneficial to health, but not all probiotics live up to their claims. To make sure the bacteria gets through to your bowels alive (after going through the harsh stomach environment), buy fresh products well within their use-by date. The number of live bacteria decreases rapidly as the product ages – particularly if it has not been stored correctly. Even half an hour in the boot of your car on a hot day is enough to kill off most useful bacteria. You can also increase the amount and quality of prebiotics in the foods and beverages you consume.

Most beneficial bacteria thrive on a healthy diet of dietary fibres and resistant starch – and these only come from the good carbs we enjoy in our meals.