5

How Ideas Matter for Political Change

Ideas, unless outward circumstances conspire with them, have in general no very rapid or immediate efficacy in human affairs; and the most favourable outward circumstances may pass by, or remain inoperative, for want of ideas suitable to the conjuncture. But when the right circumstances and the right ideas meet, the effect is seldom slow in manifesting itself.

—John Stuart Mill, Edinburgh Review (1845)1

Maggie, Mart, and the Madmen

It happened with Lenin rousing the crowds in Russia. It happened with Mao driving China into the Cultural Revolution and Great Leap Forward. It happened with Che Guevara’s motorcycle ride across Latin America, looking for fights and finding Castro’s revolution in Cuba. It is happening today in Venezuela and Bolivia, where presidents proclaim a “new” revolution in the names of Simón Bolívar and the last Incan emperor, Atahualpa. All these revolutionaries espouse an ideology known as socialism—the same ideology that transformed a third of humanity during the twentieth century. It’s an ideology that took life from the pen of Karl Marx, sitting in a library in London, writing books. Ideas have had their consequences.

On the other side of the revolution spectrum, people have advanced the ideas of economic freedom and prosperity. In 1975 an emerging leader of England’s struggling Conservative Party, Margaret Thatcher, famously slammed a book on the table in front of her colleagues. “This is what we believe,” she declared. The book was Friedrich Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty (1960), which helped shape many of the policies that Ms. Thatcher would later pursue as prime minister. Less than a generation later, when the Berlin Wall fell, post-Soviet Estonia removed trade barriers, introduced a low flat tax, and saw its economy flourish. The Estonian prime minister, Mart Laar, was a historian by profession. Years later Mr. Laar reflected, “I had read only one book on economics—Milton [and Rose] Friedman’s Free to Choose . . . I simply introduced it in Estonia, despite warnings from Estonian economists that it could not be done. They said it was as impossible as walking on water. We did it: we just walked on the water because we did not know that it was impossible.”2

While not all revolutionaries walk on water, all great revolutions are rooted in ideas. Keynes no doubt has something similar in mind when he pens his famous passage about “academic scribblers” and the battle between ideas and vested interests:

. . . the ideas of economists and philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed, the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas. Not, indeed, immediately, but after a certain interval . . . [S]oon or late, it is ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil.3

Keynes’s passage encapsulates a rich process by which even the most abstract ideas may come to have real-world consequences. From its quiet beginnings as an academic scribble, to its subtle absorption into popular belief, to its implementation by madmen walking on water, a mere idea has the power to change the world. Yet Keynes says little about how we move from the ivory tower of ideas to the average person’s opinions and from opinions to influence current events. It is Keynes’s intellectual adversary, Friedrich Hayek, who peers into the Keynesian capsule.

In a 1949 University of Chicago Law Review article, “The Intellectuals and Socialism,” Hayek describes how ivory tower ideas descend to have an influence on public opinion. Hayek begins by making a sharp distinction between “scholars” and “intellectuals.” Scholars are experts and original thinkers in specific subject areas. Intellectuals, on the other hand, are figures in society, neither original thinkers nor decisionmakers, who habitually stray from one subject to the next. This broad class of people comments on a range of weighty issues, presenting each to the general public as either good or bad ideas. Calling them “professional second hand dealers in ideas,” Hayek says the intellectual class acts like a sieve between scholars and public opinion:

The [intellectual] class does not consist of only journalists, teachers, ministers, lecturers, publicists, radio commentators, writers of fiction, cartoonists, and artists all of whom may be masters of the technique of conveying ideas but are usually amateurs so far as the substance of what they convey is concerned . . . There is little that the ordinary man of today learns about events or ideas except through the medium of this class and outside our special fields of work we are in this respect almost all ordinary men, dependent for our information and instruction on those who make it their job to keep abreast of opinion. It is the intellectuals in this sense who decide what views and opinions are to reach us, which facts are important enough to be told to us, and in what form and from what angle they are to be presented. Whether we shall ever learn of the results of the work of the expert and the original thinker depends mainly on their decision.4

While “second hand dealers” may not be the most dignified of monikers, Hayek doesn’t necessarily use it as a term of abuse. Nor does he suppose that the “intellectuals” harbor ill motives or act selfishly; in fact, elsewhere in the essay he likens them more to philosophers than to politicians. Nonetheless, Hayek’s tone is an irritated one. In a particularly feisty passage, he complains: “Even though [the intellectuals’] knowledge may often be superficial and their intelligence limited, this does not alter the fact that it is their judgment which mainly determines the views on which society will act in the not too distant future.”

Hayek argues that there is pathology among the intellectual class, a pernicious bias in how they select the ideas they favor. In the mid-twentieth century, surrounded by technological progress, the intellectuals were biased toward the application of hard science methods to design human institutions. They therefore supported government central planning of economies. This trend is deplorable in Hayek’s worldview. He derisively terms it “scientism” and teaches the dangers of its intellectual overreach. Hayek writes of the rationalism developed by Descartes (whom we met in Chapter 2) and how its mistaken leap from physical science to human affairs encourages reformers to design that which they and others could not truly understand.

Nonetheless, to most people in the middle of the twentieth century, the logic seemed airtight. If humans could control their physical world to make life better, then shouldn’t the next achievement be to control human society through centralized economic planning? The intellectuals of decades past had embraced this logic and gone to work to convince the masses, which soon placed vested interests at the mercy of the ideas that would usher in socialist central planning for a third of the world’s population. We can see why Hayek might be angry. He believes that well-intentioned intellectuals are dooming the world with their bias toward scientism. Meanwhile good ideas—namely his own classical liberalism—lie dusty on the shelf.

As we observed in Chapter 1, both the Keynes and Hayek passages imply top-down processes, from the abstract heights of academia outward and down to public opinion. Keynes’s academic scribblers are equivalent to Hayek’s scholars—they are the innovators of big ideas with the potential to change the world. It is Hayek’s intellectuals who filter the abstract into the ordinary, in a process that he says will involve “many further relays.” Over time, perhaps several generations, the course of public opinion creates opportunities for “madmen in authority” to implement the very ideas of the “academic scribblers” whom the “intellectual” class chose to ordain. Both Keynes and Hayek seem to echo Mill from this chapter’s opening quotation. When the circumstances are right, the ideas of elites, which by a point in time had soaked into people’s collective beliefs, will hold sway over public affairs—but only if their ideas overcome the interests of the status quo.

Writing in 1936, Keynes’s mention of vested interests anticipates the development of public choice analysis that would soon follow. It is not a complete theory of political economy—nowhere else in The General Theory does Keynes discuss vested interests, and he offers no analysis that would approach Tullock’s transitional gains trap, for example. Rather, the perspectives offered by Keynes and Hayek make clear that, prior to the development of public choice analysis, at least a few thinkers were concerned about the effects ideas have on outcomes in a society and the vested interests they must overcome.

Nor is the link between ideas and interests merely academic, as underscored by recent and sometimes violent revolutions in the Arab Spring that have overthrown long-standing governments. Even when there are no revolutions unfolding before our eyes, the interplay of ideas and interests still unfolds on a routine basis, with the daily increments to the roles and functions of governments. In other words, political change comes about—violently or peacefully, quickly or slowly—and all too often it is difficult to pin down exactly why it comes about, much less when. So again, we return to our three motivating questions for understanding the process of political change:

1. Why do democracies generate policies that are wasteful and unjust?

2. Why do such failed policies persist over long periods, even when they are known be socially wasteful and even when better policies exist?

3. Why do some wasteful policies get repealed (for example, airline rate and route regulation), while others endure (for example, sugar subsidies and tariffs)?

Given that public choice theory doesn’t offer a neatly packaged answer to question 3, this chapter develops a framework to understand political change as entrepreneurial action that alters the interplay of ideas and interests in shaping social institutions. To keep things as simple as possible, we anchor our framework to one of Hayek’s earliest economic theories, his theory of capital investment and economic development.5

The Relationship between Ideas and Institutions

All else being equal, given the choice, most people would want to live in a rich society instead of a poor one. Material wealth is not every person’s ultimate goal, but wealth and especially the circumstances that create wealth are directly tied to many of the good things in life that people want. At the very least, we would want to avoid poverty, where we’d have little choice but to work our children, deplete common pool resources, and worse.

To create wealth, people must first produce goods or services that others value, and people are more productive when they work with more and better capital. For example, U.S. workers don’t specialize in manufacturing as much as they did in the past, yet their productivity is very high. Like other similarly wealthy societies, the United States has invested significant amounts of capital per worker, especially capital in the form of valuable knowledge. The well-educated and well-paid scientists and engineers who design new drugs, better computers, and smartphones are just one example. As we suggested in Chapter 2, flip over your iPhone and notice the small print: “Designed by Apple in California, assembled in China.”

In the 1990s, a particularly prosperous decade, U.S. worker productivity increased dramatically. A 2001 study by the McKinsey Global Institute looked into what caused this “productivity miracle” in the U.S. economy. It turns out that some large percent of the aggregate productivity gains during this period originated in the retail sector. The study spends a lot of time talking about Walmart, especially its growing distribution network and the various economies of scale that the company had to invent for itself in order to sustain its rapid, comprehensive expansion. Walmart was busily innovating new distribution and marketing processes like warehouse and purchasing logistics, electronic data interchange, and wireless bar code scanning. Competition in the sector soon made these easily transportable innovations standard for any retail operation of significant scale, essentially forcing the entire sector to become more efficient. The innovations also migrated vertically from retailers to wholesalers, especially in industries like pharmaceuticals. These improvements raised labor productivity in retail and distribution so much that it became visible in the aggregate data for the economy as a whole.

The interesting thing about all these innovations is that none of them was directly valuable to consumers. Each was only valuable by making the retailer more efficient, thereby reducing costs and enabling it to pass these savings to its customers in the form of lower prices. The term for this is roundaboutness. Consumer value gets created by a roundabout process in which investment in higher-order goods such as distribution and network technology lowers prices and increases options for consumers. In short, better capital makes labor more productive, which creates more value for all of us as consumers.

Walmart’s inventory-tracking gizmos are what Carl Menger, a seminal figure of Austrian economics, would call “higher-order” goods, while consumer goods are things we directly enjoy like food, housing, transportation, and leisure. In other words, higher-order goods are things that help us acquire the consumer goods we really want, and thus they create value roundaboutly.

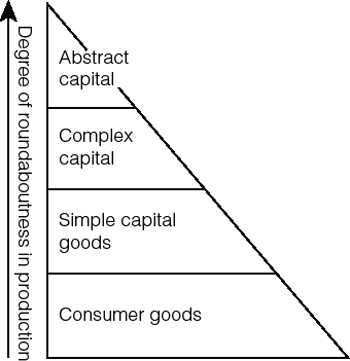

One of Hayek’s early works develops Menger’s categories into a model of capital accumulation. Figure 5.1 shows a simplified version of Hayek’s model. Consumer goods are situated at the base of the triangle. Capital comes in a variety of forms, from simple tools to more complex and abstract higher-order capital goods.

For example, even poor economies have final goods and some amount of capital goods. In agrarian societies, a farmer might plant and harvest with an ox-drawn plow and simple hand tools. With meager capital, it should come as no surprise to find that this farmer is not very productive. In such a society, the triangle is not very tall (there is little capital and little roundaboutness), nor is it very wide (there are few consumer goods). In contrast, in a high-capital economy the same farmer might use tractors with global positioning systems (GPS) and yield a hundred times more food at lower average cost.

Figure 5.1 Capital in economic development.

It’s not just the amount of capital but its composition that Hayek’s theory emphasizes. An advanced economy will have more complex and diverse forms of capital. The tractor, for example, has to be manufactured with machine tools in a factory. Whoever made those machine tools invested in even more roundabout capital. And the machine tools and factories were made possible by design and engineering principles, a type of knowledge-based capital that is still more roundabout.

The economic benefits of using more varied capital speak for themselves. In 1800 about 95 percent of the U.S. labor force worked in agriculture, while in 2000 it was less than 1 percent. The other 99 percent were not unemployed; most of them were busy providing other valuable goods and services. Put in terms of Hayek’s model, in such a society the triangle is much taller (there is more capital and more roundaboutness), and the base of this triangle is much wider (there are many more goods and services).

Returning to our Walmart example, we might think of forklifts and hand trucks as belonging in the area of the Hayekian triangle labeled “Simple capital goods.” But handheld scanners and smart conveyers would be more complex, higher-order forms of capital. And the software that lets the scanner run the inventory system is an even higher-order, even more complex capital good that would go in the area labeled “Abstract capital.”

The dimensions of the Hayekian triangle are interesting. Notice that the vertical dimension in Figure 5.1 is labeled as the “Degree of roundaboutness in production.” More roundabout production is synonymous with more investment in higher-order capital. As entrepreneurs invest and accumulate capital, you might visualize that increased investment as a vertical stretching of the triangle, making production more roundabout. As the capital investment raises productivity in the economy, this in turn creates growth in consumer value, as if the triangle were being stretched horizontally so that its base covers greater distance and the area representing consumer value is greater.

The operative question, then, is: How does an economy increase investment in higher-order capital goods? In other words, what carrots and sticks—what incentives—do entrepreneurs have when considering those very investment deals that raise labor productivity and living standards?

This brings us back to Chapter 1 and Danny Biasone’s basketball shot clock. The way people play the game depends on how the rules of the game are set up and honored. If people aren’t sure that their contracts will be honored in a few years, or if they fear that the dollars with which they will be repaid in the future will be worthless, then economic activity will suffer. But in an advanced economy like that of the United States, entrepreneurs generally have good incentives to develop new, efficient ways of doing things because formal and informal rules support innovation, entrepreneurship, and commerce. In turn, competitive markets give Walmart the incentive to implement these innovations into their routine operations. These incentives to innovate and implement exist in large part because of a legal system that protects property rights, honors contracts, and maintains a sound currency, which in turn give people sure footing when striking deals over long periods of time.6

In other words, individuals have an incentive to invest in capital when the right institutions are in place. The institutions themselves are not as visible as a new machine or factory, but they play a similarly critical role in the creation of wealth. Economists have long recognized the importance of institutions, and, more recently, they have sought to estimate it empirically.

In 2006 a group of economists at the World Bank published a 188-page study titled, “Where Is the Wealth of Nations?” The study attempts to measure “intangible capital” by country. Natural capital consists of a country’s forests, fields, waterways, and similar resources. Produced capital is more what Hayek had in mind, things like machinery, infrastructure, communications, and other things that would count as higher-order capital goods in Figure 5.1. According to the World Bank study, intangible capital includes the human capital that people have accumulated as well as “social capital, that is, the degree of trust among people in a society,” and a number of “governance elements that boost the productivity of the economy.” The study concludes that wealth increases with an efficient judicial system, well-defined property rights, and accountable government.7

Hayek calls sound institutional arrangements—in particular the protection of property rights and enforcement of contracts—the rule of law. By restraining governments from arbitrary property takings and contract reversals, he argues, the rule of law makes investment more efficient and less risky, which in turn facilitates economic growth. A recent study by Paul Mahoney looks closely at thirty-three years of economic growth patterns in 102 countries. Following Hayek, Mahoney reasons that the rule of law is stronger in English common law countries than in French civil code countries. As compared to the more constructivist French civil law, Hayek argues, common law is more organic, emerging over time in response to the needs of a people, and building on the precedent (and knowledge) of previous rules. Hayek’s theory finds much support in Mahoney’s regression results, which show the thirty-eight common law countries having significantly better economic growth than the sixty-four civil code countries, even after controlling for important variables like education for human capital and investment for physical capital.8

So it is not just physical capital that matters; it is also the formal and informal institutions that support economic activity. If so, then the next question is: What makes a society predisposed to establishing sound institutions? To begin thinking about the social forces that shape institutions, we take our first cue from the Victorian historian Lord Acton, who in 1877 writes:

The history of institutions is often a history of deception and illusions; for their virtue depends on the ideas that produce and on the spirit that preserves them, and the form may remain unaltered when the substance has passed away.9

Acton suggests that institutions and ideas are intertwined with one another. Ideas can be the impetus for institutional change. On the other hand, ideas can also be constraints on institutional change, or “the spirit that preserves” the status quo. In either sense, ideas and institutions are closely bound up in each other.

Of all the Nobel Prize winners in economics, the 1993 laureate Douglass C. North (born 1920) most closely takes up Lord Acton’s suggestion. North is the scholar who innovated the rules-of-the game concept of institutions. In his Nobel address, North writes, “Institutions form the incentive structure of a society and the political and economic institutions, in consequence, are the underlying determinant of economic performance.”10 In more recent work, North turns to the question of what forms institutions. He has been exploring cultural, historical, and other human factors that seem to propel societies toward adopting particular rules over others. He homes in on ideas, in particular how individual cognitive processes organize the information that makes up our real world, in all its messiness, and how individual beliefs spread into collective beliefs. In a slender 2005 book, North speculates about that world: “Successful economic development will occur when the belief system that has evolved has created a ‘favorable’ artifactual structure . . .”11 In this sense, North parallels Hayek, who argues that institutions in support of the rule of law emerged where belief systems placed a high value on individual liberty, namely by the spread of the English common law system.

One formal institution that mutually reinforces the rule of law is the federal separation of powers, such as that seen in the U.S. system. North and his frequent coauthor, Barry Weingast, analyze federalism as a “market-preserving institution.” The idea is that a well-functioning separation of powers helps to prevent policies that deter economic development by undermining security of property and contract or by politicizing the currency.

In turn, they argue that market-preserving institutions have their roots in society’s shared beliefs about innovation and commercial life. In a landmark 1989 paper, North and Weingast argue that England’s seventeenth-century civil war jolted prevailing belief systems in English society, shifting them to be more wary of authoritarian structure and likewise more welcoming of market institutions like property and contract. This spurred the emergence of stock exchanges and other financial intermediaries, thus giving gradual rise to England’s lead in history’s most important period of capital investment, the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution is alive and well in cutting-edge research on the power of ideas. Joel Mokyr’s important book The Enlightened Economy (2010) traces the remarkable growth of England’s economy between 1700 and 1850 to earlier innovations—not just in technology and machinery but also in ideas and institutions. Mokyr argues that the Enlightenment sowed into the shared beliefs of Britons the ambitions of progress, the achievements of science, and the virtues of commerce. With these ideas to swaddle market institutions, England became a cradle of the Industrial Revolution and reaped the reward of becoming the place where capitalist invention was itself invented.

Deirdre McCloskey’s recent works argue that the line between ideas and economic development is more direct than even North, Mokyr, or others allow. In volume two of a planned six-volume treatise, McCloskey’s Bourgeois Dignity (2011) deconstructs and ultimately rejects the theory that institutional change was the proximate cause of the Industrial Revolution. Institutions of property predate the era, McCloskey argues, so if institutions were a sufficient explanation then we’d have seen the Industrial Revolution emerge much sooner. But there was, according to McCloskey’s research, a surge in certain beliefs and attitudes about the right time. A review of documents from the era reveals increasing discussion of and attention to such things as “temperance, courage, justice, faith, hope, and love.”12 For McCloskey, the story of economic development is one of virtue and vice, not of institutions and mere incentives. In Chapter 2 we were reminded by the School of Athens that individual morality is the foundation of political philosophy. Today’s economic historians are building a parallel argument, pointing out that individual virtues are also the foundation of a market society.

And here, like elsewhere, the new economic histories are rediscovering the work of Adam Smith. In his Lectures on Jurisprudence, for example, Smith argues that individuals naturally desire to participate in society at the level of ideas. In fact, he says that our natural propensity to participate in commercial life—to “truck, barter, and exchange”—is rooted more deeply in our desire to participate in a social life based on civil discourse and shared beliefs: “The real foundation of [the division of labor] is that principle to persuade which so much prevails in human nature.”13 In short, the division of labor is a natural propensity because humans naturally want to cooperate with each other, and this cooperation makes both parties better off.

Ideas as Higher-Order Capital Goods

At first glance, all this interaction appears to be incredibly complicated. Apparently, if we want to understand political change, then we have to account for a lot of complex things in society, including the ideas of academic scribblers, formal and informal institutions in that society, the shared beliefs and attitudes of ordinary people, and all the various ways that ideas and institutions shape incentives for people to be for or against the status quo. That’s a lot to handle.

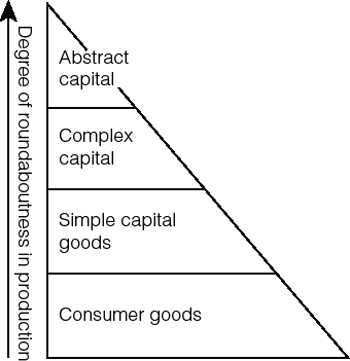

Figure 5.2 organizes everything into a simple adaptation of Hayek’s capital model. The triangle shows the nexus of ideas, institutions, and incentives that generate social and political outcomes in a society. At the base of the triangle is the state of affairs. Are we a prosperous society? Are we a free and virtuous society? As we have been discussing, these are intertwined questions. The triangle situates incentives as proximate causes of outcomes in society, which reflects the bedrock principle, taught in almost every economics textbook, that incentives determine people’s decisions. But what shapes people’s incentives? The triangle shows that incentives in turn depend on the interplay of institutions and ideas. The adapted Hayekian triangle helps reduce the complexity of the problem and lets us consider all the various questions about political change within an integrated whole.

Figure 5.2 Ideas and institutions as higher forms of capital.

In short, ideas are a type of higher-order capital in society. Like a society that is poor in capital and therefore produces little consumer value, a society that is poor in ideas and institutions will have bad incentives and therefore few of the desirable outcomes that people want.

It’s also intuitive to think of institutions as depending on the climate of ideas. Per Mokyr and McCloskey, societies are predisposed to establishing sound institutions when shared beliefs in society extol information sharing, innovation, entrepreneurship, and commercial life in general.

Nonetheless, the nexus of ideas, institutions, and incentives is not the entire story. Does all the “action” originate within the ideas section of the triangle? If so, is the flow of ideas a one-way street from elites down to the masses? Of course not. Figure 5.2 is not meant to suggest that the interplay of ideas, institutions, and incentives is linear. There is observable feedback between and within the areas of the triangle. Nor are academic scribblers the only source of ideas in society because there is much bottom-up input into people’s shared beliefs. Finally, the ideas of academic scribblers are not produced in a vacuum but within a social context at a particular time and place.

Consider, for example, Karl Marx. He sat in a library and wrote about the alienation of workers as a consequence of the division of labor. But the location of the library and the time of his writing matter greatly. Marx wrote from London in the middle of the nineteenth century, in the cradle of the Industrial Revolution. The social upheaval associated with this era was real. One could walk the streets of London and see poor factory workers. Never mind that these impoverished masses were transplants from an even more impoverished countryside; the suffering was nonetheless new and very real, and as a result there was a receptive audience for radical ideas about social organization. Had Marx lived instead in the nonindustrialized societies of twelfth-century Italy or fifteenth-century Spain, his theory of alienation likely would not have been so well received.

But for thinking about political change, this Hayekian structure gets us asking the right kinds of questions. At the base of the triangle, we treat political outcomes as public choice theory does, as the product of exchange among rationally self-interested people who respond to incentives. It’s the rules of the political game that deserve our focus, not politicians’ personalities or party affiliations. At the level of institutions and ideas, what matters is the confluence of top-down and bottom-up beliefs and ideas. Most importantly, we focus on the agents of change, those entrepreneurs of ideas and new institutions who find the “loose spots” in Figure 5.2 and exact political change: John Maynard Keynes, Karl Marx, all those whose ideas conspire with outward circumstances.

The Complex Formation of Individual Beliefs: Bottom Up and Top Down

Circumstances matter. We start life as a bundle of genes, prewired with a bundle of strengths and weaknesses and inclinations. Next, we spend a couple of decades soaking in the ideas, attitudes, and experiences of youth. Then we go vote. As complex and intricately woven characters, we choose our madmen in authority.

What views bear on the shape of government when a person, young or old, casts a vote? Each person’s beliefs take shape under circumstances that vary by time and place, by culture and convention, and by a number of personal factors unique to individuals. The diversity of individual experiences maps onto the variety of ways that individual beliefs emerge, are nurtured, promoted, and ultimately adopted or rejected.

For example, talk to your elders who lived through the Great Depression. Ask them about the things that matter in life. They’ll probably mention patriotism, survival, the honor of a day’s paid work, and good government. For a different perspective, talk to people who grew up behind the Iron Curtain, in Soviet bloc Eastern Europe. You may hear them talk of their parents working in jobs picked for them by the Party or how they quickly learned to watch over their shoulder for the secret police, knowing that the world might never consist of more than the four walls assigned to them by the housing authority. You’ll get a different set of beliefs about the proper role and function of government.

When an academic scribbler comes up with a new idea, it has to resonate well with widely shared beliefs, which in turn must overcome the vested interests at the table. Many forces come together to explain political change, even though it may seem like coincidence of time and place.

The Importance of History

Five years after “The Intellectuals and Socialism,” Hayek organized a collection of essays about history, called Capitalism and the Historians (1954). At the heart of this book is the question: How do ordinary people acquire their conceptions of history?

Although in the indirect and circuitous process by which new political ideas reach the general public the historian holds a key position, even he operates chiefly through many further relays. It is only at several removes that the picture which he provides becomes general property; it is via the novel and the newspaper, the cinema and political speeches, and ultimately the school and common talk that the ordinary person acquires his conceptions of history. But in the end even those who never read a book and probably have never heard the names of the historians whose views have influenced them come to see the past through their spectacles.14

This passage has strong parallels with the passage we quoted earlier. Hayek’s “second hand dealers” from before are now his “many further relays.” What’s more, the anchor to historical record lets us see the process Hayek describes unfolding in our own experience, in our modern world. Consider, for example, how most of us view World War II. Having a father or grandfather who fought in it provides an inside view. For a more expansive, less personal view, there are impressive histories, like H. P. Wilmott’s The Great Crusade and John Keegan’s The Second World War. Yet even high-minded readers are also bound to take in historical novels like Herman Wouk’s romantic saga The Winds of War and journalistic accounts like Tom Brokaw’s The Greatest Generation. And for almost anyone who reached adulthood before the end of the twentieth century, it’s not possible to think of wartime North Africa without visualizing Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca, a testament to the power of imagery in the course of ideas.

The Importance of Technology

Even if we presume that the influence of ideas is mostly top down, the process is more complex than in Hayek’s day because of subsequent changes to the market for “second hand dealers.” As ideas spread through different mediums and technologies, for example, the influence of the second hand dealers changes dramatically. Movies have been a particularly powerful medium. For example, today’s younger generations are especially likely to view World War II through the lens of a handful of great movies—Band of Brothers, Flags of Our Fathers, Saving Private Ryan, and Schindler’s List. This helps explain why the one man who directed these movies, Steven Spielberg, is a force in Hollywood (where ideas are distilled into entertainment) as well as in Washington (where ideas are distilled into law).

Talk television and radio have been highly influential as well. For years Oprah Winfrey recommended books and important thinkers to her millions of viewers, and sales figures showed that America took her advice. Soon a number of presidential candidates, including Barack Obama, were lining up to appear on her show and win her endorsement. From another point of view, once candidate Obama became president critics such as Bill O’Reilly and Glenn Beck argued that his administration’s policies promoted socialism in America. Glenn Beck told his listeners about Hayek’s Road to Serfdom, and sales of Hayek soared. CNBC reporter Rick Santelli ignited the Tea Party movement with a live television rant about the government’s bailout of Big Auto.

As “second hand dealers” in ideas, Hayek likely would count among today’s intellectuals such figures as Oprah and O’Reilly, Glenn Beck and Rachel Maddow, Rush Limbaugh and Jon Stewart. And he would count far more of them today than at any time before. The climate of ideas has far more competitors in it compared to the past six or seven decades. Intellectuals are not as unified behind a single ideology as they were during the middle of the twentieth century. Most commentators and public intellectuals after World War II believed that government should command the most critical aspects of society. In contrast, today’s highly competitive intellectual landscape supports an array of viewpoints that transcends a simplistic left-right categorization.

In fact, in important ways, the marketplace of ideas is more competitive and less dominated by ideology than at any time in history. There are well over 6,000 think tanks around the world, for example, with about nine in ten having been founded since the end of World War II.15 The evolution of news media has generated a diversity of viewpoints that could scarcely have been imagined in the age of Walter Cronkite, and that’s just considering radio and television. If today’s consumer of ideas has more options than could even have been imagined only a few decades ago, it seems almost a quaint notion that a few biased “intellectuals” will decide which ideas filter into the mass of public opinion. With a click of the mouse or television remote, ordinary people can control more of the information they receive.

Thus, today, the marketplace for ideas is far more competitive than it was in 1949, or even 1999. It’s probably true that Oprah and Jon Stewart have affected people’s beliefs about human affairs, but they haven’t held the monopoly on public opinion suggested by Keynes’s academic scribblers or Hayek’s intellectuals. It’s not all top down. If ideas about the proper role of government emerge at least partially from the bottom up, it bears taking a slight detour into the science of individual beliefs, how they form, and why some are not likely to change anytime soon.

The Importance of Biology and Culture

Ideas are accepted or rejected by individuals, but each individual comes to his or her set of beliefs in a specific context. These ideas are shaped by nature as well as nurture.

By nature, we mean genetic endowment, what each individual inherits at birth. Obvious examples include physical traits like body type, hair and eye color, hereditary disease, and so forth. Can genetic differences explain why millions of people have certain ideas about family, faith, law, and politics? Perhaps it can, at least in part. For example, it is reasonable to expect that, as compared to other societies, there may be notably different laws and policies in a society with a large percentage of its members suffering from anxiety or depression. Ideas about policy are simply in front of a different audience, who may see those ideas differently or even be affected differently by them.

By nurture, we mean the environment in which an individual is raised, including family, faith, community, culture, and country. What language a person speaks is a product of environment. For example, one of us speaks broken Spanish, and the other is fluent. Unless you knew which of us has lived in Latin America for many years, you might guess wrong based on our surnames. Like language, peoples’ worldviews and ideologies are influenced by family, friends, teachers, religious leaders, politicians, and any number of other people, living or dead, famous or not famous. Remember the essay on Japanese politics that Mrs. Parsons made you write in the eighth grade (or that paper on French philosophy or Italian history)? Not only did it reflect her love of that country’s culture; it may have instilled the same in you. Your minister’s devotion to the poor may have done more than encourage you to volunteer your summer vacations as a teenager; it may have influenced how you approach social policy today.

The biological sciences that describe the influence of nature and nurture are complicated, at times controversial, and certainly beyond the scope of this book. A few contributors, however, tie in directly and help us better understand how nature and nurture may ultimately affect how we choose the rules by which we live together with other human beings.

Consider, for example, the work of evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins. His 1976 classic The Selfish Gene ignited a decades-long conversation on traits and characteristics that tend to endure in plants, animals, and that most social of animals, humans. In a sense, the book is an extension of the work of Charles Darwin, especially the idea of natural selection, by which better-performing traits enhance survivability and thus are more likely to be passed on.

Twenty-six years before Dawkins’s classic, the economist Armen Alchian penned a related article, “Uncertainty, Evolution and Economic Theory.” While focused on economic behavior, the link to evolution is clear. Adaptive, imitative, and “trial-and-error” behavior are modes of economic competition. Firms do not maximize profits, as the standard neoclassical model dictates. Firms instead continuously adapt in a marketplace that punishes inefficient use of resources; otherwise they don’t survive. Efficient behaviors, like better-performing physical traits, are more likely to survive. Other economists have tried to link biology and economics, with varying degrees of success. No less a pioneer economist than Alfred Marshall, one of the founders of neoclassical economics, observes a connection in his 1890 text. But one need not see biology and economics as equal to recognize that both can be evolutionary.

For economists and other social scientists, the big questions are not about blue eyes or baldness; the interesting themes strike closer to the core of survival traits like aggression and altruism, competition and cooperation. As Adam Smith and his forbears believe, the mix of these and other qualities are more likely to make a human society free, peaceful, and prosperous, or instead oppressed, violent, and poor. To his credit, Dawkins is careful to avoid playing psychologist. Rather, he argues that individual selfishness and individual altruism coexist as part of “gene selfishness” that is rooted in survival—that is, in the desire to perpetuate or, in Dawkins’s terminology, to replicate. The selection that drives this process does not exist to benefit the group (whether market or species); it occurs to benefit the gene (Alchian’s firm or individual people).

But how do individuals relate to the rest of their group, and in what ways do their ideas, attitudes, beliefs, and the like get transmitted over time? Is there a genetic (nature) component to such transmission? Here Dawkins is more careful, though his speculation is worth examining, as it has been a part of the social sciences for more than three decades. Here is a key passage:

The gene, the DNA molecule, happens to be the replicating entity that prevails on our own planet. There may be others . . . But do we have to go to distant worlds to find other kinds of replicator and other, consequent, kinds of evolution? I think that a new kind of replicator has recently emerged on this very planet. It is staring us in the face. It is still in its infancy, still drifting clumsily about in its primeval soup, but already it is achieving evolutionary change at a rate that leaves the old gene panting far behind. The new soup is the soup of human culture.16

Dawkins introduces a new word to our vocabulary—meme—to describe culture as such a replicator. A meme is, in short, a unit of cultural transmission. Examples can range from the mundane (a tune, a phrase, a fashion), to the practical (ways of making cookware or building arches), to the sublime (faith). To what extent do humans hold memes? How are they transmitted? And what effect does such transmission have on individual attitudes and beliefs about the rules they should use to guide behavior? These questions remain of interest to social scientists of all sorts, but the answers are incomplete. What seems clear, however, is that something—an idea, an attitude, a skill, a habit—is transmitted. The cause and effect may be unclear, but the interrelatedness of it all—a type of soup of life—remains.

Ten years later, Richard Lewontin, Steven Rose, and Leon Kamin weighed in with their book and its telling title, Not in Our Genes. The authors offer a contrasting position to Dawkins’ Selfish Gene, and the debate has been fierce. If taken to an extreme, their argument against nature produces a straw man, a point easily grasped by anyone with a serious genetic disorder, let alone the rest of us with bad vision or flat feet. On the other hand, Lewontin, Rose, and Kamin have an important point to make. Much of who we are as individuals is a product of social conditioning, and much though not all of this conditioning can be shaped and improved. A summary of their argument is made clear with a quotation: “We have the ability to construct our own futures, albeit not in circumstances of our own choosing.”17 A fervent desire to “construct our own futures” sounds inherently human, and indeed it is. Great minds from across the ideological spectrum maintained as much. Once again, Karl Marx gets to the pith of the matter: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they make it under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.”18

The roles of nature and nurture, then, may not be mutually exclusive. This is an argument closely associated with the cognitive neuroscientist Steven Pinker. According to Pinker, it is helpful to think about how nature and nurture interact:

In some cases, an extreme environmentalist explanation is correct: which language you speak is an obvious example, and differences among races and ethnic groups in test scores may be another. In other cases, such as certain inherited neurological disorders, an extreme hereditarian explanation is correct. In most cases the correct explanation will invoke a complex interaction between heredity and environment: culture is crucial, but culture could not exist without mental faculties that allow humans to create and learn culture to begin with.19

In other words, history and culture and personal experience matter, but they do not tell the entire story. In most cases, who we become is not entirely because of a “bad seed” (nature) or an abusive caregiver (nurture), powerful as such effects may be. Our genetic and environmental influences interact in a way that is at once complex and powerful. Parsing the two may be a fool’s errand; ignoring either in its entirety may be worse.

As the anthropologists Robert Boyd and Peter Richerson argue, cultural evolution is a process determined “not by genes alone” (a catchy line that also is the title of their book). They describe culture as “information” that is “acquired or modified by social learning, and affects behavior.”20 Individuals choose among an infinite array of attitudes, beliefs, customs, and dogmas. Over time these become part of the culture. Individuals consider new ideas or information within a context that includes all information that is commonly held.

The Importance of Geography

On the other hand, a different form of nature argument says that biology may be trumped by geography, at least according to Jared Diamond. In his successful 1997 book Guns, Germs and Steel, Diamond argues that the earliest causes of success of certain societies precede political and religious institutions, deriving instead from climate, types of domesticated animals, and ease of human travel. Better soil and climate helped agriculture to emerge earlier in some places as compared to others, for example, which is why the Fertile Crescent got its name. Regions with navigable rivers and natural harbors were more conducive to migration and commerce. If agricultural development favored certain regions (neither too hot nor too cold, for example) and if trade followed specific routes (more often East–West than North–South), then specialization, trade, and economic development would be more likely in some places than in others. And if traders also brought exposure to new ideas, then a fertile intellectual climate might be as predestined as a good harvest.

The Importance of Psychology

The ideas that work their way into public opinion are not always good ones. Research that blends fundamental insights of psychology and economics has shed much light on how—if not why—people often hold seemingly irrational preferences. For example, the psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky have shown how individuals often revert to the status quo, to that with which they are familiar, even when an obviously better option is available to them. Similarly, individuals often place greater weight on avoiding losses than on achieving gains, when economic theory predicts that a rational person would weigh them equally under the same odds. For example, the average person prefers a certain payout of $500 over a 50 percent chance of winning $1000 combined with a 50 percent chance of winning nothing, even though the expected value of those two scenarios is the same.

Such research offers insights into human behavior in everyday economic affairs, in business and politics and more. For example, how a company structures its retirement plan often will determine the extent to which employees participate in it. If a company’s policy (or a government rule) establishes that employees automatically will have a minimum percentage of their salary deposited into a personal retirement account, participation in the savings plan will be greater than if employees are given the option of contributing to this same type of account. Even if employees may choose to opt out of such savings plans, there generally is more saving if the default policy is for the employee to participate. As we saw in the discussion of public choice theory in Chapter 3, rules matter. The insights of evolutionary psychology simply remind us that rules should take into account people’s predispositions.

Kahneman, a psychologist, shared the 2002 Nobel Prize with an economist, Vernon L. Smith (born 1927), for their contributions to understanding how individuals make decisions under different circumstances and with different frames. To the extent that those frames change—either as a direct result of social policy or an indirect consequence of other factors—people’s views may change as well.

Individuals also have biases when it comes to politics, and these biases affect how they participate in politics. The economist Bryan Caplan’s 2007 book The Myth of the Rational Voter identifies four areas where voters’ beliefs clash with the actual effects of public policies. For example, Caplan points to surveys where most voters support import tariffs to support domestic job growth, yet the vast majority of economists agree that such policies would not produce the intended effect and in fact are quite harmful.

And likewise, Kahneman and Tversky’s behavioral anomalies don’t go away. Behavioral research has shown it can be disruptive and difficult for people to change their minds about the world. If you grew up believing that the sun revolves around the earth, for example, and if your family and friends believe the same, it can be startling to discover proof that the solar system is heliocentric—so much so that you may choose to ignore such proof. When individuals’ understandable, perhaps even rational, biases inform their support for certain public policies over others, politicians might have little choice but to enact the inefficient policies that a free and democratic people demand. As H. L. Mencken once quipped, “Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.”21

From Collective Belief to Institutional Change

Aggregation forms another layer of the problem. How do we go from genetic predisposition and personal psychology—the combination of nature and nurture that makes up each individual’s unique history—to collective belief? The cognitive anthropologist Dan Sperber argues that, in many ways, the spread of ideas and beliefs resembles the spread of infectious diseases. This theory explains why statistical models that help the U.S. Center for Disease Control estimate the spread of deadly viruses have a new set of users: anthropologists and other social scientists who model the dissemination of ideas. If voters are biased toward certain interests or have mistaken beliefs about the consequences of government, they might support bad policies. Their biases could spread through the marketplace of ideas, and they can be as difficult to overcome as some biological epidemics.

The idea is not that radical or unfamiliar, even to nonscientific audiences. Malcolm Gladwell’s best-selling books, Outliers and The Tipping Point, show how the right conditions (place of birth, ethnicity, years of practice, or working at something others ignore), combined with an accumulation of other factors (shared beliefs and attitudes, for example), can make some outcomes almost inevitable. Yet the same author’s other best-selling book, Blink, demonstrates how quickly we process information with little apparent thought, almost as if we were hardwired to see some things and not others.

Other experts argue that the way we are wired has changed over time, as humans adapt to changes in our environment. Over the last few decades, much light has been shed on this question by evolutionary psychology, a field that borrows heavily from anthropology, genetics, psychology, and economics. Robert Wright, a journalist and former science editor, provides one of the earliest contributions to this field of thought in a classic work, The Moral Animal: Why We Are, the Way We Are: The New Science of Evolutionary Psychology. Matt Ridley, a science writer with a doctorate in zoology, follows with The Origins of Virtue: Human Instincts and the Evolution of Cooperation. Paul Rubin, an economist, offers Darwinian Politics: The Evolutionary Origin of Freedom.

A central theme in these popular explanations is that human beings have evolved to better take advantage of the benefits of cooperation. This does not mean that selfishness or self-interest has been purged from the human gene pool. Rather, societies converge on institutions that channel self-interest (individual survival) into activities that promote the general interest (group survival). Human interaction has evolved in ways that allow people to experience the benefits of cooperation, and social norms develop in support of mutual gains. The lesson is that societies evolve to avert the Hobbesian jungle and instead adopt rules that let people generate Adam Smith’s invisible hand.

In a more recent book, The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves (2009), Ridley takes the metaphor of natural selection in social arrangements even further, using it to explain the ongoing success of some societies. Ridley argues that the wealth and well-being of a society is not determined by the average IQ of its brightest intellectuals—disheartening news for academic scribblers and social critics everywhere—nor is it determined by the average IQ of the masses. Rather, argues Ridley, a society’s material well-being hinges on its ability to integrate the best ideas available.

Taking a figurative cue from Darwin, Ridley argues that societies evolve to better and better conditions when “ideas have sex”—the process whereby ideas interact and produce new ideas. As with natural selection in its original sense, the ideas that best meet our needs gain a reproductive upper hand. In the long run—and evolution is about the long run—better ideas tend to be recognized and rewarded and replicated. This optimistic tone has much in common with contributions from scientists like Richard Dawkins and economists like Armen Alchian.

In fact, optimism about our ability to improve the human condition has a long history in social and political thought, dating at least to Adam Smith, who lays out clearly why specialization and the division of labor promote social cooperation and, ultimately, human well-being. It is in The Theory of Moral Sentiments that Smith first points the way to social cooperation. Here Smith argues that it is our ability to engage in sympathy, putting ourselves in the shoes of others, that allows us to form rules of just conduct. A social environment that combines rules of just conduct with an imagination that can think of the needs of others will facilitate exchange, production, and cooperation, the secret ingredients to human prosperity. A good environment for the marketplace of ideas matters to the flourishing of a society.

Two centuries after Adam Smith, his namesake, Vernon Smith, was awarded the Nobel Prize for pioneering the field of experimental economics and, like Kahneman, contributing to our understanding of human decision-making. Vernon Smith’s work combines his findings in laboratory and field experiments with a deep reading of political philosophy, especially the classical liberals. In his Rationality in Economics: Constructivist and Ecological Forms (2008) the modern Mr. Smith describes the cognitive origins of two types of rules in society, designed and emergent. The first, constructivist rationality, invokes Bacon and Descartes (whom we met in Chapter 2) to present the case for reason as the basis for rules in society. A single mind (or a small group of minds) develops solutions that apply to all. The effects can be beneficial, such as Internet protocols that help organize all communication between very different kinds of information systems and technologies. The effects can also be devastating, especially when a select few are given economic control of an entire society; just ask anyone who has ever lived in the former Soviet Union or today’s North Korea. And the effects sometimes can be negligible, for example when a law is technically on the books but not enforced.

The second, ecological rationality, is the set of informal rules and norms in society that coordinate behavior spontaneously. People reach positive-sum outcomes without a central plan, thus obviating the need for hierarchical, central control. Instead, evolution can favor the best ideas. In his 2002 Nobel lecture, Smith offers a dozen observations on human behavior in general and markets in particular. Among these are two gems. First, he notes that “markets are rule-governed institutions.” Second, he argues that “rules emerge as a spontaneous order—they are found—not deliberately designed by one calculating mind.”22

The 2009 economics Nobel Prize winner, Elinor Ostrom (1933–2012), spent her career studying the spontaneous design of rules that emerge when people are allowed to coordinate behaviors over time. Ostrom studied resources to which everyone has common access, or “common pool resources.” Too easily scholars fall into a false dichotomy of centrally planned versus private property regimes. When in the real world, many valuable resources, such as inland fisheries and underground water basins, don’t respect borders and can’t easily be centrally planned or treated as private property. Ostrom’s research shows that the right type of rule can emerge through repeated trials among the same groups of people. The best outcomes tend to be when the rules reflect local knowledge about the resource and how other locals are using it. Oftentimes the outcome is best under a system of communal rights, with well-defined rules regulating access and use that are appropriate to the circumstances on the ground.23

The implications of Smith’s and Ostrom’s ideas for social and political change are immense. For the most part, rules do not have to be imposed hierarchically, even if in the beginning a brilliant mind conceives them and in the end a dictator decrees them. Rather, rules emerge through a variety of parallel processes through which ideas about just conduct and a better society slowly work their way into a society’s shared beliefs systems and eventually become embodied in its shared institutions. There’s no equilibrium in this kind of economics. And whether the social scientist concludes that people are rational or not, as Vernon Smith likes to observe, in the end, “markets will do their thing.”

The Framework

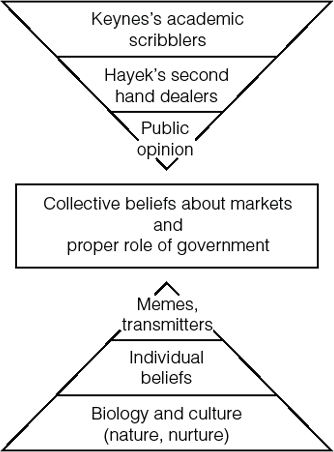

If we think back to the triangle in Figure 5.2, the area at the top labeled Ideas gives us a lot to consider. Through a number of parallel forces at the individual and group levels, shared beliefs about the proper scope and function of government take shape, and their continual evolution exerts pressure for political change. Figure 5.3 organizes these forces into a simple hourglass, showing both the top-down and bottom-up components involved in the formation of collective beliefs.

Figure 5.3 The top-down and bottom-up process of idea formation.

In the top section of the hourglass, ideas take shape from the pens of Keynes’s academic scribblers. Certain ideas are then selected by Hayek’s “second hand dealers” competing in a marketplace of ideas. These ideas are then selectively absorbed by masses of people into the general climate of public opinion and collective beliefs about commerce and government. It is these ideas that will shape the message delivered by madmen in authority.

Every hourglass can be turned over. In the bottom section of the hourglass we lay out the individualistic origins of beliefs as we’ve discussed them these last few pages. Starting from the bottom, we have “Biology and culture” representing the influences of genes, upbringing, life-changing experiences, and so forth. People’s “Individual beliefs” come out of this experience, and “Transmitters” make ideas available for selection by others, as with Dawkins’s meme. Unlike the single top-down cone from above, the highly individualist bottom section has a cone for each person in society. In the United States there are about 300 million bottom cones like this. Each has its own story, of course, because each represents an individual who has come to his or her beliefs over a lifetime.

Completing the relationship between these top-down and bottom-up processes, an increasingly large number of individuals in a society may, through their combined experiences and endowments, come to a particular belief that they may or may not even know they share. These beliefs in turn may be given voice by an academic scribbler and then looked on favorably by intellectuals. In this way, a seemingly self-generating, bottom-up process ultimately may merge into the type of top-down influence that Keynes and Hayek described.

At the confluence of these top-down and bottom-up forces, collective beliefs take shape about the proper role and function of government. These beliefs are continually evolving under the influence of ideas circulating in society. Now when we think back to the nexus of ideas, institutions, and incentives in Figure 5.2 we have a road map for thinking about what forces might cause a shift. Figure 5.4 combines our hourglass with the adapted Hayekian triangle to complete our framework for understanding political change. On the left is the hourglass of ideas taking shape through both top-down and bottom-up forces in society. This shift might take place over many years—in a roundabout process that involves many further relays—and may perhaps not even be visible to the casual observer. As this process shapes collective beliefs about the proper role and scope of government, new ideas move their way to the right side of the diagram. As ideas shift in the top of the triangle on the right, they exert pressure on institutions, which in turn shape incentives and outcomes. To create political change, this pressure on institutional arrangements must be sufficient to overcome status quo interests. For those ideas that eventually do surmount vested interests, new institutional arrangements emerge, which in turn present policymakers and ordinary people with revised incentive structures, and outcomes will change from there, for better or worse.

Figure 5.4 The framework of political change.

Significantly, rule change is seen as an emergent process in this model. It is a product of rational individuals engaging in that most human of activities—exchange. The exchange of ideas and their effects on institutions and incentives in a society always take place in the context of a particular time and place, and it cannot be planned.

Nonetheless, the temptation to plan is strong. Indeed, a casual glance at Figure 5.4 might lead one to conclude that the process of political change is mechanistic, a somewhat complicated system which, if properly engineered, can yield the social outcomes that people desire. But a more careful look suggests a more profound conclusion: There is no starting point. The search for such a magical point—a lever with which to change the world—is a fallacy common to madmen and intellectuals everywhere. It is akin to the constructivist error Hayek warns us about. Because humans are rational creatures, and because they respond to incentives, we can and should expect them to adjust to changing conditions in their world, to include new rules.

Answering Question 3: Why Only Some Failed Policies Get Repealed

The wasteful and unjust policies that simply do not seem to get reformed—Tullock’s transitional gains trap—may describe the vast majority of political outcomes. But they do not describe all of political reality. Sometimes, things can actually get better. Sometimes, reform is possible.

The opportunity for reform emerges in specific issues or policies, in particular times and in particular places. In our language, a “loose spot” emerges in the nexus of ideas, institutions, and incentives. It becomes possible for a new idea to overcome the vested interests. But this possibility must first be noticed by alert people in the society. In short, political change happens when entrepreneurs notice and exploit those loose spots in the structure of ideas, institutions, and incentives.

In the following chapter, we discuss case studies of exactly this type of political change, focusing on ideas that have gone on to change institutions and the incentives they create. Then, in the concluding chapter, we look specifically at the political and intellectual entrepreneurs who produce institutional change in our framework.