Courtesy of Tammi Pass

Today’s digital cameras have the ability to take pictures and store them on memory cards, and later on computers, in various image formats. There are three formats available in some cameras and only two in others. Additionally, there are often various levels of image compression—squeezing the image into a smaller size—within the formats, which saves space.

Image formats vary in their ability to store levels of color, which is called bit depth. In this chapter we will examine the various image formats, their names and sizes, and their pros and cons. The formats available in your camera are usually accessible from a menu item called image quality, or something similar. Many cameras also give you external controls to allow rapid format changes. Check your user’s manual and read about your camera’s image quality settings so you can see what formats your camera uses.

Image quality is simply the types of images (file formats) your camera can create, along with the amount of image compression that reduces the size of the file. When you take a picture, it goes through camera processing and then is stored on your camera’s memory card. You can transfer it to your computer later.

An image file—similar to any file that can be stored on a computer—has a file name that specifies what type of file it is. Image files end in various three-letter extensions, such as .jpg (JPEG) or .tif (TIFF). An example of a file name for an image is DSC_1234.jpg.

There are three image formats available in many cameras:

JPEG

JPEG

TIFF

TIFF

RAW (the name varies among camera brands)

RAW (the name varies among camera brands)

Some cameras use only two formats: JPEG and RAW. Unless you are using a Panasonic camera, you will not see an actual file format or image quality called RAW. The word “RAW” simply indicates a camera’s best-possible image quality format. A RAW image is not yet an image; it is a potential image that allows you to change settings after the fact. Many professionals and enthusiasts shoot in RAW format for maximum image quality. RAW images require you to convert the files to a final format (such as JPEG) so that you—not the camera—make the final decisions about the appearance of the image.

All of the camera’s settings are permanently applied to a JPEG or TIFF image before it is written to the camera’s memory card, but a RAW image file is merely raw data from the imaging sensor that stores the camera settings temporarily. The camera settings can be changed later in your computer without harming the image.

Unlike JPEG or TIFF formats, the camera settings are not permanently applied to the image data in a RAW file. A RAW file is written to the camera’s memory card with virtually no processing by the camera. We’ll talk more about RAW images in an upcoming section.

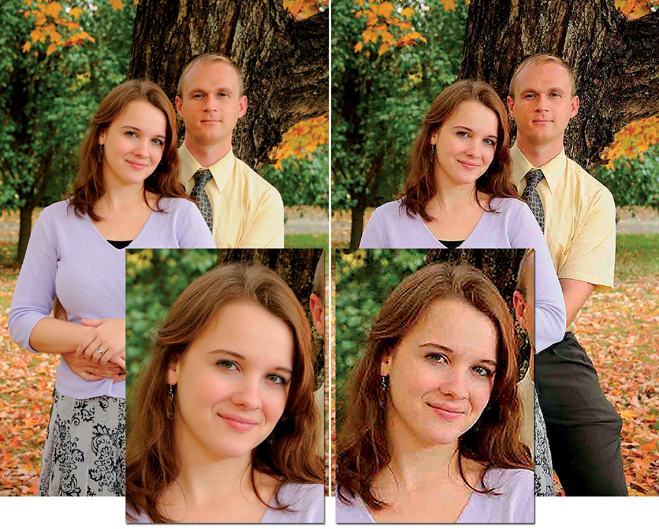

Figure 6.1: A JPEG image with no changes (upper left) and the same image modified and saved multiple times

Let’s discuss each image quality file format and explore its benefits and problems. You may want to use different formats at different times, so it is a good idea to learn about each format your camera uses.

JPEG, which stands for Joint Photographic Experts Group, is an extremely popular image quality setting. Most cameras default to this setting from the factory since the resulting images are immediately usable by virtually all image display devices. When you take a picture in JPEG format, no further processing in the computer is required unless you want to change the appearance of the image.

The JPEG format is used by photographers who want excellent image quality but have little time for, or interest in, post-processing (changing how the image looks) or converting their images to another format. They want to use their images immediately when they come out of the camera, with no major adjustments.

The JPEG format applies your chosen camera settings to the image when it is taken. The image comes out of the camera ready to use, as long as you have exposed it properly and have configured all the other settings appropriately for the image. If the camera settings and exposure were not applied correctly, a JPEG image is hard to salvage. Why?

JPEG is a lossy format: it throws away image data because it compresses the data each time the file is modified and resaved. You cannot change and save a JPEG file in your computer more than a time or two before recompression losses degrade the image. A JPEG file is smaller than a RAW file or a TIFF file because a JPEG file is compressed by the camera. If you open the image file in your computer, make changes, and then resave the file, the image is compressed again, with more loss of image quality each time you repeat the process.

After you change and save a JPEG file multiple times, all that extra compression simply ruins the file and leaves ugly artifacts (blocky-looking spots) in the image (figure 6.1). If you are committed to shooting JPEG files, you must be very accurate in how you expose the image because adjusting it and saving it again degrades the picture.

However, since no post-processing is required, the JPEG format allows you to use the image more quickly. A person who shoots a large quantity of images, such as a journalist or someone who doesn’t have time to convert RAW images, usually uses JPEG format. That describes many photographers. Nature or portrait photographers might want to use RAW format since they have more time for post-processing images and wringing the last drop of quality out of them.

Your camera offers multiple JPEG modes so you can set the compression level for your JPEG images. Each mode provides a different level of lossy image compression. Higher levels of compression are more lossy.

Camera manufacturers call their JPEG compression modes by different names. They are usually available in three levels that correspond to large, medium, and small file sizes. Nikon uses the names Fine, Normal, and Basic for the three sizes, and Canon calls their modes Superfine, Fine, and Normal. Check your camera manual for a menu item named something like JPEG compression to see what names your camera uses. JPEG file names end with .jpg (e.g., DSC_1234.jpg).

I cannot tell what name your camera uses for JPEG compression, so I will use the generic names Large, Medium, and Small. Normally the compression ratios for these three file types are as follows:

JPEG Large: Compression approximately 1:4

JPEG Large: Compression approximately 1:4

JPEG Medium: Compression approximately 1:8

JPEG Medium: Compression approximately 1:8

JPEG Small: Compression approximately 1:16

JPEG Small: Compression approximately 1:16

This means that if your camera produces 25 megabytes (MB) of raw image data, a JPEG file will be compressed to approximately these sizes (geek alert):

A JPEG Large file with a 1:4 compression ratio will be 1/4 the size of the raw image data (25 MB × 0.25 = 6.25 MB).

A JPEG Large file with a 1:4 compression ratio will be 1/4 the size of the raw image data (25 MB × 0.25 = 6.25 MB).

A JPEG Medium file with a 1:8 compression ratio will be 1/8 the size of the raw image data (25 MB × 0.125 = 3.1 MB).

A JPEG Medium file with a 1:8 compression ratio will be 1/8 the size of the raw image data (25 MB × 0.125 = 3.1 MB).

A JPEG Large file with a 1:16 compression ratio will be 1/16 the size of the raw image data (25 MB × 0.0625 = 1.6 MB).

A JPEG Large file with a 1:16 compression ratio will be 1/16 the size of the raw image data (25 MB × 0.0625 = 1.6 MB).

As you can see, JPEG is a useful format for storing a lot of images. Just remember this fact: when a JPEG compression operation takes place on the file, the camera will average the colors and contrast and throw away a large amount of color data (because it is a lossy format). The finest color gradations are eliminated from the file, and all the color is crammed into a maximum of 256 levels for each of the three color channels—red, green, and blue (RGB). See the upcoming section called “Channel and Bit Depth Tutorial” for what this means.

The human eye compensates for small color changes quite well, so the JPEG compression algorithm works very well. A useful thing about JPEG is that you can vary the file size of the image, via compression, without affecting the quality too much in the initial capture.

The positives of JPEG format are as follows:

Allows the maximum number of images on a memory card and computer hard drive

Allows the maximum number of images on a memory card and computer hard drive

Allows the fastest transfer from the camera memory buffer to the memory card in the camera

Allows the fastest transfer from the camera memory buffer to the memory card in the camera

Compatible with everything and everybody in imaging

Compatible with everything and everybody in imaging

Uses the printing industry standard of 8 bits (256 color levels per RGB channel)

Uses the printing industry standard of 8 bits (256 color levels per RGB channel)

Produces high-quality, first-use images

Produces high-quality, first-use images

No special software is needed to use the image right out of the camera (no post-processing)

No special software is needed to use the image right out of the camera (no post-processing)

Immediate use on websites with minimal processing

Immediate use on websites with minimal processing

Easy to e-mail and transmit via other methods on the Internet

Easy to e-mail and transmit via other methods on the Internet

The negatives of JPEG format are as follows:

Lossy format

Lossy format

Multiple changes and resaving can degrade image quality

Multiple changes and resaving can degrade image quality

TIFF (Tagged Image File Format) is a file format that does not require post-processing for immediate use, yet it can later be modified and resaved in a computer without data loss. Many cameras do not support the TIFF format because the files are rather large and therefore slow to process and transfer, and they take up a lot of space on memory cards and computer hard drives.

TIFF is not a lossy format because the camera does not compress the file before saving it to the memory card. Later, in the computer, you can modify and save a TIFF file over and over without compressing it and throwing away data. TIFF is a well-known format that is usable by most image processing software.

Some people use TIFF mode for their initial shooting (if their camera supports it). You could use TIFF mode if you do not want the lossy compression of a JPEG and if you want to adjust the images later in your computer without fear of quality loss.

Most cameras that support TIFF format create 8-bit TIFF files. Since many cameras shoot natively in 12 or 14 bit, there is some initial data loss when saving to the TIFF format because the 12- or 14-bit images are converted to 8-bit TIFF files (see the upcoming section called “Channel and Bit Depth Tutorial”).

After shooting in TIFF format and saving an image file to your computer, you can modify it over and over without additional losses. The primary problem with TIFF files is that they are huge and will slow down your camera while it saves the files. TIFF file names end with .tif (e.g., DSC_1234.tif).

The positives of TIFF format are as follows:

Very high image quality

Very high image quality

Excellent compatibility with the publishing industry

Excellent compatibility with the publishing industry

Lossless format; uses no compression and loses no more data than the initial camera conversion from 12 or 14 bits to 8 bits

Lossless format; uses no compression and loses no more data than the initial camera conversion from 12 or 14 bits to 8 bits

Images can be modified and resaved an endless number of times without losing image data

Images can be modified and resaved an endless number of times without losing image data

Does not require software post-processing during or after download from the camera, so the image is immediately usable

Does not require software post-processing during or after download from the camera, so the image is immediately usable

The negatives of TIFF format are as follows:

Files are very large; requires large and expensive memory cards and hard drives

Files are very large; requires large and expensive memory cards and hard drives

In-camera image processing is slower; limits the number of pictures you can take in rapid succession

In-camera image processing is slower; limits the number of pictures you can take in rapid succession

Generally too large to e-mail and transmit via other methods on the Internet

Generally too large to e-mail and transmit via other methods on the Internet

RAW format is a proprietary format that your camera uses. A RAW file is simply raw camera data from your camera’s imaging sensor, along with information on how your camera was configured when you took the picture. It is not yet an image and must be converted to some other format during post-processing.

Different camera brands have different names for their RAW files. Some manufacturers have multiple RAW file formats. Plus, there is one generic format. The following is a list of RAW format file extensions by camera brand:

Canon: CRW, CR2

Canon: CRW, CR2

Fuji: RAF

Fuji: RAF

Leica: RAW, RWL

Leica: RAW, RWL

Minolta: MRW

Minolta: MRW

Nikon: NEF, NRW

Nikon: NEF, NRW

Olympus: ORF

Olympus: ORF

Panasonic: RAW, RW2

Panasonic: RAW, RW2

Pentax: PEF, PTX

Pentax: PEF, PTX

Samsung: SRW

Samsung: SRW

Sigma (Foveon sensor): X3F

Sigma (Foveon sensor): X3F

Sony: SRF, ARW, SR2

Sony: SRF, ARW, SR2

There is also an open-standard RAW image format that was developed by Adobe, called DNG, which stands for digital negative. You can save the image file from any camera into the DNG format, in case you are worried that your manufacturer will not support its proprietary RAW format for the long term, or you would simply rather store your images in a non-proprietary format. There is a good article at this website about the DNG format: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_Negative.

With Canon cameras, the RAW file names end with .crw (e.g., DSC_1234.crw). With Nikon cameras, the RAW file names end with .nef (DSC_1234.nef). Each camera manufacturer has its own proprietary name (or multiple names). Only Panasonic and Leica RAW files end with .raw.

Now, let’s talk about RAW quality. I use the RAW format about 98 percent of the time. I think of a RAW file the way I thought of my slides and negatives a few years ago. It’s my original image that must be saved and protected.

It is important that you understand something very unusual about RAW files. They are not really images—yet. A RAW file is composed of black-and-white sensor data and camera setting information markers. The RAW file is saved in a form that must be converted to another file type to be used in print or on the web.

When you take a picture in RAW format, the camera records the image data from the sensor and stores markers for how you have set your camera picture controls for things like color, sharpening, contrast, saturation, etc., but it does not apply this information to the image in a permanent way. Later, in your computer postprocessing software, the image will appear onscreen with these settings temporarily applied, just so you can see how the image would look with no changes made. However, it is simply a temporary interpretation of data. You must post-process the file—making any changes you find necessary to the look of the image—and then save the picture to a final format, such as JPEG, before it is a usable image.

For example, if you don’t like the white balance you selected when you took the picture, simply apply a new white balance and the image will appear as if you had used that setting when you took the picture. If you initially shot the image using high color saturation settings and now want to use more subdued colors, all you have to do is apply the new color settings during post-processing, before the final conversion to another image format, and it will be as if you used those settings when you first took the picture.

This is quite powerful! At the time of capture, virtually no camera settings are applied to a RAW file in a permanent way. That means you can apply completely different settings to the image in your computer software and it will appear as if you had used those settings when you first took the picture. This gives you a lot of flexibility later. After you post-process a file, you can convert it to JPEG format, which sets the image markers permanently, or you can convert it to TIFF format, which sets the markers but allows you to modify the image later without suffering compression losses.

RAW format is generally used by photographers who are concerned with maximum image quality and who have time to convert the images in a computer later.

The positives of RAW format are as follows:

Allows the manipulation of image data to achieve the highest-quality image

Allows the manipulation of image data to achieve the highest-quality image

All original detail stays with the image for future processing

All original detail stays with the image for future processing

The camera does not manipulate image data; it is untouched and pure

The camera does not manipulate image data; it is untouched and pure

Allows you to convert files with the more powerful processor of a computer

Allows you to convert files with the more powerful processor of a computer

Gives you much more control over the final look of the image; you make the final decisions

Gives you much more control over the final look of the image; you make the final decisions

The 12-bit or 14-bit format provides maximum color information

The 12-bit or 14-bit format provides maximum color information

The negatives of RAW format are as follows:

Not often compatible with the publishing industry, except after conversion to another format

Not often compatible with the publishing industry, except after conversion to another format

Requires post-processing with manufacturer-provided proprietary software or third-party software

Requires post-processing with manufacturer-provided proprietary software or third-party software

Larger file sizes require larger storage media

Larger file sizes require larger storage media

No standard file format; all formats are proprietary (except for the open DNG format)

No standard file format; all formats are proprietary (except for the open DNG format)

Industry standard for home and commercial printing is 8 bit, not 12 or 14 bit

Industry standard for home and commercial printing is 8 bit, not 12 or 14 bit

Some cameras offer multiple compression modes for RAW images, so check your camera manual! If your camera offers RAW compression, you will have to weigh the benefits. A RAW file can be large because it contains so much information in its uncompressed form.

My camera offers lossless and visually lossless compression modes. The lossless mode provides 20–40 percent file size reduction with no loss of quality—in other words, the compression is fully reversible, like a ZIP file. The visually lossless mode has even higher compression that ranges from 40–55 percent file size reduction. It does have a little loss of image data, although the manufacturer claims that the compression losses cannot be seen. My camera also has an uncompressed RAW mode, which I rarely use because the files are too large, like TIFFs.

I use the lossless RAW compression mode because I see no particular need to store files larger than they have to be, especially since there is no data loss in the image. If your camera has a true lossless RAW compression mode, I would seriously consider using it. Any other RAW compression modes that cause data loss are completely uninteresting to me.

Unfortunately, some lower-end DSLRs and ILCs force a lossy compression mode on your RAW images, whether you want it or not. This is one of those irritating things that convinces me to buy cameras in the semipro range so I have choices.

Your camera will come with free manufacturer-supplied RAW conversion software. There are several aftermarket RAW conversion applications available, such as Bibble, RawShooter, Capture One, and ACDSee Pro. Most of these programs are available for Windows and Mac. Here are links to these aftermarket companies:

Bibble Labs: http://bibblelabs.com/

Bibble Labs: http://bibblelabs.com/

RawShooter: http://rawshooter.en.softonic.com/

RawShooter: http://rawshooter.en.softonic.com/

Capture One: www.phaseone.com (click the software link)

Capture One: www.phaseone.com (click the software link)

ACDSee Pro: www.acdsee.com

ACDSee Pro: www.acdsee.com

Additionally, you can use Adobe Photoshop or Lightroom for conversions from RAW to other file formats. Before you shoot in RAW format, it’s a good idea to install your conversion software of choice so you’ll be able to view, adjust, and save the images to another format when you are done shooting. You may not be able to view RAW files directly on your computer unless you have RAW conversion software installed.

When you try to view a RAW file on your computer, you may not be able to see thumbnail (small) pictures in your computer file management software (such as Windows Explorer or Mac OS X Finder) unless you have a proper codec1 installed. When you install the free RAW conversion software from your camera manufacturer, it may install the proper codec. Install your conversion software, and then investigate whether or not you can see small thumbnail images in the computer’s file browser. If not, you may need to take extra steps.

Some computer operating systems provide a downloadable patch or codec that lets you see RAW files as small thumbnails in its file management software. As this book is being written, I can find codecs in Google searches for Windows 7, Vista, XP, Linux, and Mac OS X. In your favorite search engine, use this text string to search for available codecs: “download RAW viewer codec”. You can often find a free one, but be careful that you don’t go to a website promising the moon and delivering malware instead.

There are reliable third-party companies, such as Ardfry Imaging LLC (www.ardfry.com), that offer various 32- and 64-bit RAW codecs for a small fee. I bought the Ardfry version for my computer. If you’re running 64-bit Windows Vista or 64-bit Windows 7, you may want to check out Ardfry’s website or do a little research on the Internet to see what else is available for viewing RAW files as thumbnails on your computer.

Many cameras give you the best of both worlds by letting you shoot in RAW and JPEG formats at the same time. It takes more memory card space than just shooting in one format, but it gives you both formats for every shot. Check your camera manual to see if your camera offers this dual-mode shooting capability. If it does, you can have a JPEG for immediate use and a RAW file for storage purposes (and later postprocessing into very high-quality images).

What does all this talk about bits mean? Why would I set my camera to use 14-bit depth instead of 12-bit depth in RAW mode? This short tutorial explains bit depth and how it affects color storage in an image.

First, it’s important to understand that an image from your camera has three color channels—red, green, and blue (RGB). Most current cameras give you the choice of shooting in 12- or 14-bit mode. If you are shooting in 12-bit mode, your camera will record up to 4,096 colors for each channel—there will be up to 4,096 different reds; 4,096 different greens; and 4,096 different blues. That’s lots of color! In fact, there are almost 69 billion colors. If you set your camera to 14-bit mode, it can store 16,384 different colors in each channel. Wow! That’s quite a lot more color—almost 4.4 trillion shades.

Is that important? It can be, since the more color information you have, the better the color in the image—if it has a lot of color. I always use the 14-bit mode. That allows for smoother color changes when there is a large range of color in an image. I like that!

Of course, if you save an image as an 8-bit JPEG or TIFF, most of those colors are compressed, or thrown away. Shooting a JPEG image in-camera (as opposed to a RAW image) means that the camera converts the image in a 12- or 14-bit RGB file to an 8-bit file. An 8-bit file can hold 256 different colors per RGB channel—more than 16 million colors.

There’s a big difference between the number of colors in a RAW file and the number in a JPEG file. That’s why I always shoot in RAW; later I can make full use of all those potential extra colors to create a different look for the same image.

If you shoot in RAW format and later save your image as a 16-bit TIFF file on your computer, you can store all the colors you originally captured. A 16-bit file can contain 65,536 different colors in each of the RGB channels. Many people save their files as 16-bit TIFFs when they post-process RAW files, especially if they are worried about the long-term viability of their camera’s proprietary RAW format.

TIFF gives us a known and safe industry-standard format that will fully contain all image color information from a RAW file. Unfortunately, TIFF files are huge. Many people are looking into the Adobe DNG format as an alternate RAW format in hopes that it will remain viable for the long term.

If your camera manufacturer stands behind its proprietary RAW format and keeps on supporting it, you’ll be fine. If not, many aftermarket software vendors should step up and support the older RAW formats.

Which image format do I prefer? Why, RAW, of course! However, it does require a bit of commitment to shoot in this format. The camera is simply an image-capturing device, and you are the image manipulator. You decide the final format, compression ratio, size, color balance, etc. In RAW mode you capture the best image your camera can produce. It is not modified by the camera software and is ready for your personal touch. No in-camera processing allowed!

If you get nothing else from this chapter, remember this: if your camera processes an image in any way, it modifies or throws away image data. There is a finite amount of data for each image that can be stored on your camera’s memory card and later on your computer. With JPEG, your camera optimizes the image according to the assumptions recorded in its memory. Data is thrown away permanently, in varying amounts.

If you want to keep all of the image data that is recorded in your images, you must store your originals in RAW format. Otherwise, you will never again be able to access that original data to change how it looks. A RAW file is the closest thing to a film negative or a transparency that your digital camera can make. That’s important if you would like to modify the image later. If you are concerned with maximum quality, you should probably shoot and store your images in RAW format. Later, when you have the urge to make another masterpiece out of the original RAW image file, you’ll have all of your original data intact for the highest-quality image.

If you’re concerned that the RAW format may change too much over time to be readable by future generations, you might want to convert your images to TIFF or JPEG files. TIFF is best if you want to modify them later. I often save a TIFF version of my best files in case RAW changes too much in the future, but interestingly I can still read the RAW format from my 2002-era Nikon D100 in Nikon’s current RAW conversion software. Why not do a little more research on this subject and decide which you like best?

My Recommendation: I shoot in RAW format for my most important work and JPEG fine for the rest. Some people find that JPEG fine is sufficient for everything they shoot. Those individuals generally do not like working with files on a computer or do not have time for it. RAW files are not usable images and must be converted to another format. However, RAW provides the highest possible quality your camera can create—if you have the time and inclination to post-process the images yourself. You will use both RAW and JPEG, I’m sure. The format you use most often will be controlled by time constraints and your digital workflow.

In digital photography we must use new technology and learn many new terms and acronyms. However, by investing a little time to understand these things we become better digital photographers. In the next chapter, we will learn about three important digital technologies: the histogram, color space, and white balance.

The histogram is a tool you can use to validate the exposure for each of your images immediately after you shoot it. It is a digital readout that shows you the RGB channels in a graphical format that can protect you from missing good shots. I sincerely recommend that you learn to use the histogram.

Color space helps you match your camera to software and image display devices so that the colors will be consistent. It also affects how much color gamut (range of color) your camera can capture.

White balance is a way for you to match the camera to the light in which you are taking pictures. Otherwise, you may have odd tints in your pictures and not know why.

Learn to use these three tools and you will be far ahead of most digital photographers. A true enthusiast!