Chapter 4

Spring came early in 1942, as it often does in California’s Salinas Valley, where vast fields of lettuce, chard, spinach, and artichokes stretch from the Gabilán mountains in the east all the way to the great blue crescent of Monterey Bay in the west. Less than a century after Americans from eastern states swept into California in search of gold, displacing the original Mexican families from the valley’s sprawling ranchos, white Americans now owned most of the land.

But it was mainly Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese immigrants who worked that land. It was they who grew, harvested, and shipped east the bulk of the nation’s fresh green produce, they whose labor had, by the 1930s, turned the valley into “America’s Salad Bowl.”

The work was tough, unrelenting, and poorly paid, and so were many of the kids who grew up in the valley. Few were tougher than sixteen-year-old Rudy Tokiwa. Slight of build, born prematurely, and asthmatic, Rudy had always been a fighter.

On the day of the Pearl Harbor attack, he was standing in a field of lettuce, leaning on a hoe. His sister, Fumi, brought him the news, running across the field toward him, waving her arms and yelling.

Rudy had been alarmed but not really surprised. His first thought was Well, it had to happen. Then, almost immediately, a second thought—a question—came to mind. If this meant war, war with Japan, what would he do if called upon to fight?

For Rudy, that was a complex question. Like many young Japanese Americans, Rudy had spent time in Japan—living with family members, learning the language, and getting to know his parents’ culture. As a schoolboy in his family’s ancestral prefecture, Kagoshima in southern Japan, he found Japanese life to be far harder and harsher than he had expected.

When he was thirteen, he and his classmates had to do military training. They could be summoned by bugle from their beds at any hour of the night and sent out on military exercises in the countryside. Sometimes the maneuvers went on for forty-eight hours straight, with the teenagers stumbling across fields, staggering under the weight of heavy packs. If Rudy hadn’t remembered to have food ready to bring with him, he went hungry.

Rudy also witnessed firsthand how hard everyday life was in Japan. A US oil embargo, designed to punish Japanese aggression in China, meant that buses, cars, and taxis ran on coal rather than on gasoline. As a result, the air was polluted and sooty. Consumer goods were scarce, and necessities like rice were rationed.

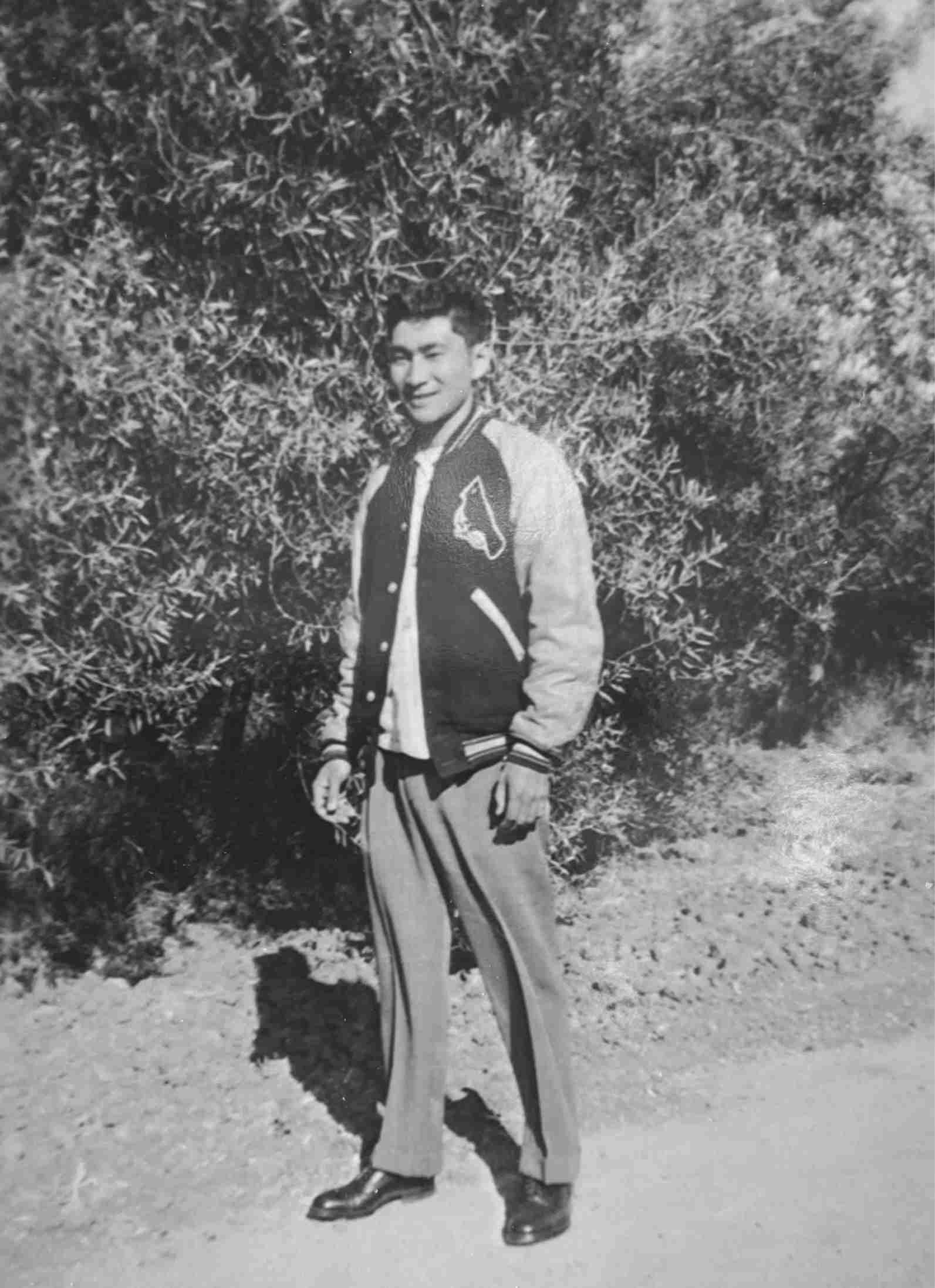

Rudy Tokiwa.

The national mood darkened under the strain of the oil embargo, and it seemed that war against America was inevitable. By the fall of 1939, Rudy’s Japanese uncle decided it would be prudent to send his nephew home.

Without much difficulty, Rudy stepped back into the all-American life he had known before his time abroad. He and his mostly white friends from school hung out at soda fountains, went to the movies, tinkered with cars. Lean, lithe, and hardened by his experiences in Japan, he took up gymnastics, track, and wrestling. Lightly built as he was, he nevertheless joined the Salinas Cowboys, his high school’s football team.

But Rudy’s outlook on life was not the same as it had been before he left for Japan. He felt that he had become a better young man there: tougher, better able to cope with adversity, more aware of the virtues of hard work and discipline. He came home deeply proud of his Japanese heritage and conscious of how isolated and besieged the Japanese felt on the world stage.

He knew—far better than most Americans—just how close war was, how inevitable it seemed from the Japanese point of view. And so he was not surprised when his sister caught up with him in the lettuce field on December 7 and told him the news.

That evening, the Tokiwa family did what thousands of Japanese families across America were doing. They gathered up family photographs and Japanese dolls and works of Japanese literature and threw them on the fire. They smashed Japanese gramophone records. They took apart Buddhist and Shinto shrines. They gave away—to astonished neighbors—lovely kimonos, antique vases, and heirloom samurai swords. They discarded anything made in Japan—cameras, binoculars, dinnerware. Rudy’s father, Jisuke—a US Army veteran from World War I—carefully laid his service uniform on top of a pile of clothes in an old steamer trunk, to be sure that anyone opening the trunk would see it first.

The next morning, as Rudy and his brother, Duke, were walking to school, half a dozen boys stepped in front of them, jabbed fingers in their chests, and snarled, “Them dirty Japs. Let’s beat them up.” Rudy and Duke exchanged glances. Then Duke growled, “Aw, we can handle them.” The brothers cocked their fists, but before they could engage, a voice behind them shouted, “All right, you Tokiwa brothers, step aside. We’ll handle it.” It was a good portion of the Salinas Cowboys football team. The bullies took off running.[15]

But when Rudy and Duke entered the school building and walked down the halls, more kids began jeering at them: “There go them Japs.” Rudy stormed into the principal’s office and said that he and his brother were going home. The principal let them go, but not before making it clear he thought Rudy was a troublemaker.

There was more trouble at home. FBI agents broke down the front door and ransacked the house, pulling out drawers and dumping their contents on the floor, rummaging through closets, climbing into the attic to search for shortwave radios, binoculars, cameras—anything that might be useful to saboteurs or spies or suggest loyalty to the Empire of Japan.

When one found Jisuke’s World War I uniform, he held it up and asked, “What’s this?”

“That’s my uniform,” Jisuke replied quietly.

“This is an American uniform.”

“Well, I was in the American army. I went to France.”

“Aw, the American army never took no Japs.” The agent threw the uniform on the floor and trampled it underfoot.

That was too much for Rudy. He leaped to his feet and screamed, “Go to hell! Go to hell!”[16] His parents restrained him, but Rudy stood seething until the agents had gone.

Now, eight weeks after Pearl Harbor, Rudy was even angrier. First, his parents had been told they couldn’t travel more than twelve miles from home without permission, which meant they couldn’t get into downtown Salinas to buy things they needed—groceries and household goods and farm supplies. Then, when his sister, Fumi, had gone to a nearby farm store to buy seed, she’d been quietly told to come back later when there weren’t any white customers in the store to see the transaction.

And rumors were circulating. Word was that thousands of Japanese American families might soon be forced out of their homes and locked up like criminals. That wasn’t likely, thought Rudy. Not whole families. After all, second-generation Americans of Japanese descent—Nisei like himself—were citizens of the United States. At Salinas High he’d learned about the Constitution. American citizens had rights. They couldn’t just lock them up for nothing. But what, he wondered, would become of his parents?