Chapter 15

The vessels carrying the 442nd across the Atlantic and into the war joined a much larger convoy, and now more than ninety ships surrounded theirs, extending all the way to the horizon in every direction. Navy destroyers and cruisers on the convoy’s flanks protected the ships from the German submarines they all knew might be lurking below the waves.

By day, porpoises cruised alongside. From time to time, whales surfaced, exhaling long, sonorous plumes of spray. Enormous jellyfish, white and pink, floated by. At night, the sea itself lit up as they slid over its surface, millions of phosphorescent organisms glowing green. It was, Fred Shiosaki thought, one of the most beautiful things he had ever seen.

By and large, the men weren’t afraid. They didn’t yet know enough to be afraid. But they had been away from home for a long time already. They yearned for the parents and siblings and friends they had left behind. At night, lying in their berths, they reached out and touched the things they had brought with them, things from home, things they hoped would carry them through the battles to come.

Some reached for crucifixes, some for small figures of the Buddha. Some had Bibles, some love letters from girlfriends back home. Some had rabbits’ feet to bring good luck, some Saint Christopher medals for divine protection. Chaplain Hiro Higuchi had pictures of his wife, Hisako, his seven-year-old son, Peter, and Jane, the newborn daughter he had not yet met. One of the men in Kats’s artillery unit, Roy Fujii, had a Honolulu bus token, which he wore on a chain around his neck. He planned to use it after the war to get from the docks in Honolulu back to his parents’ house.

Sus Ito, another of Kats’s artillery buddies, had a white senninbari his mother had sent him. Emblazoned with the image of a tiger—a symbol of safe homecoming—the traditional warrior’s sash was embroidered with a thousand individual stitches, each made by a different woman with red silk thread to confer good luck, protection, and courage. Sus kept it folded up in his pocket, close to his heart.

Rudy Tokiwa also had received a gift from his mother. At Poston, Fusa had plucked a single grain of brown rice out of a hundred-pound sack of white rice. Somehow, it had survived the rice-polishing machinery. She sewed it into a pouch that Rudy now wore around his neck. When she sent it to him, she said, “This rice kernel was real lucky . . . It’s the only one that lived through it and was able to keep this husk on. So I’m sending you this so that you’ll come home to us.”[48]

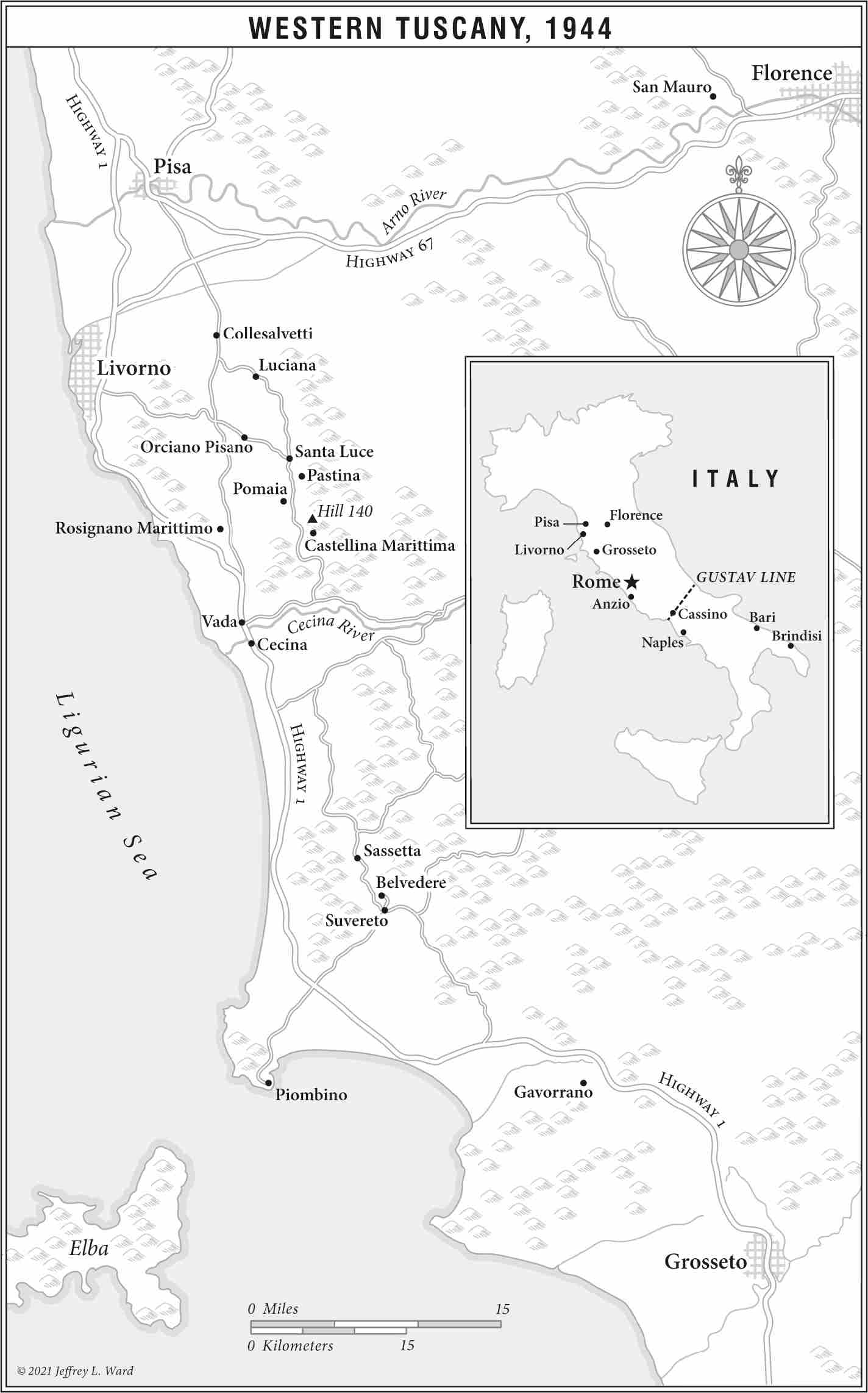

Kats’s 522nd Field Artillery Battalion docked in Brindisi—on the heel of the Italian boot—on May 28, 1944. From there, the men traveled by rail, in rickety cattle cars, northwest across Italy to rendezvous with the rest of the 442nd in Naples. The ride was slow and jolting, but, despite the discomfort, Kats was fascinated by his first glimpses of Europe. The scenery was lovely: gray-green olive trees, their trunks black and gnarled; sepia-colored hills; ancient villages perched on hilltops. It was hard to believe that this was a country at war.

But a few hours into the trip, when the train stopped in a bigger town and Kats climbed down from his boxcar to stretch his legs and look around, he found buildings crumpled by artillery fire and tanks, the rubble pushed into heaps by army bulldozers. Throngs of people—old men, women, and children—approached him, desperate, their hands outstretched, asking for food, for chocolate, for cigarettes, for help.

Worst of all was the children. Half-starved, they roamed the streets in small bands. Some wore cast-off German army jackets, others moth-eaten woolen trousers. Most were barefoot or wore tattered shoes.

When they saw Kats’s American uniform, they ran up and clustered around him, their faces begrimed, their hair matted, their eyes hollow. They pleaded with him, calling him Joe, as they did every GI in Italy. He could not turn a street corner without encountering more of them.

He dug into his kit, pulled out his rations of chocolate and fig bars and cigarettes, and tossed them to the boys. But around the next street corner there were always more.

On the other side of Italy, the main body of the 442nd arrived in Anzio, just south of Rome, and were landed by flat-bottomed landing craft onto the beachhead the Allies held there. Fred Shiosaki, weak from seasickness, walked down the ramp and glanced warily around him. Then he hoisted his gear and began marching with the rest of K Company through the shattered remains of Anzio’s waterfront. The town was a hellish landscape of rubble, trenches, and barbed wire. Allied troops had been storming ashore here for five months under almost continual German fire. Only in the last few days had the Germans finally been driven back toward Rome.

Now the men of K Company arrived at their assigned area for making a camp, on a grassy, wildflower-strewn hillside five miles east of Anzio. Exhausted, and out of shape after nearly a month at sea, they threw down their gear, sat on the ground, and began picking through their K-ration boxes, trying to find something palatable to eat.

On the hike in, some of them had bartered with locals, exchanging cigarettes for bunches of sweet, white onions, baby carrots, and bags of string beans to supplement their rations.

While they were sitting in the afternoon sun, eating and looking out over Anzio and the turquoise sea beyond, news began to filter through. At the same time as they were boarding their landing craft the previous day, tens of thousands of men like them were pouring off similar craft in northern France, in a place called Normandy, plunging into the cold Atlantic, wading ashore onto the beaches into gales of machine-gun and artillery fire. The much-anticipated Allied invasion of northern Europe had finally begun. The news about D-Day heartened the Nisei soldiers. Maybe this war they were about to become part of would be short and relatively easy.

Kats was chatting with George Oiye and Sus Ito nearby when one of their officers hurried up and told them to dig foxholes. Although the Germans were retreating north, they still had some very big guns within range. Suddenly, shells came screaming over their heads. To Kats, they sounded enormous, like washing machines hurtling through the sky. His stomach tightened. He dove for his foxhole. They all did. The barrage was short-lived, but when it was over and Kats climbed out of his foxhole, he noticed he’d gone weak in the knees with fear. The men dusted themselves off and laughed about what had happened. At least now they’d been under fire.

Then, as a full moon rose above the dark Italian hills, the black forms of German bombers appeared in the sky overhead. The Nisei soldiers dove for their foxholes and hunkered down again. The ground trembled with the concussions of bombs and occasionally a deeper roar and a more violent trembling when towers of flame and smoke rose from the munitions dumps down by the beach.

As soon as they realized they were not the target, the men peered over the edge of their burrows, scared but exhilarated too. The German planes finally peeled away and disappeared over the horizon, and the men crawled out of their foxholes again, talking excitedly, their hearts thumping.

The next afternoon, the men of the 442nd traveled to a new encampment, where they came across some old friends. For the Buddhaheads in particular, it was a joy to meet up with the men of the 100th Infantry Battalion. They sat in circles on the grass swapping news, talking story, showing one another photographs and letters from home.

It didn’t take long for the 442nd men to see that these weren’t the same guys they had known back home, nor were they the swaggering recruits with whom they had been briefly reunited at Camp Shelby. The men of the 100th had survived months of brutal fighting in southern Italy, and it had taken a toll on them.

Sometimes they looked off into space or got up and walked away in the middle of a conversation. They weren’t unfriendly, but the new arrivals could see at a glance that there was something hardened about them now.

The next day, the 100th was formally attached to the 442nd RCT. In recognition of their extraordinary valor in southern Italy, the men of the 100th were allowed to keep their original designation and were called the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate). Now, finally, the Nisei soldiers were all together, a single all–Japanese American fighting force.

Over the next two weeks, Nisei troops traveled north by truck, creeping toward the front lines and the German forces in western Tuscany. With each stop, their living conditions grew more spartan. There were no tents now. They slept in hay barns or under the stars. The civilians they encountered were, if anything, even poorer and more desperate here than those in Naples and Anzio. The faces of some were blackened with soot from living in caves, cooking over charcoal fires, eating whatever they could scavenge. And yet, as they passed some farmhouses—those that were still intact—Italians, mostly older people, ventured cautiously out to greet and encourage them.

As they approached the front lines, the terrain began to change too. The open coastal plain gave way first to rolling hills and then to forested ridges rising up toward mountain ranges. The Nisei troops began to see something most of them had never seen before: dead German soldiers, lying sprawled in fields or in ditches. The 442nd men stared silently at the corpses. The 100th guys didn’t even seem to notice them.

On June 25, the men clambered out of their trucks and marched fifteen miles up narrow, winding roads into the hills. Shells whistled regularly over their heads now, fired from somewhere behind them—their own artillery pounding whatever it was that lay in the hills ahead.

When they encamped that night, Chaplains Yamada and Higuchi gathered as many of their men as they could, and they knelt together in the dirt and prayed. Whether they were religious or not, whether they were Buddhist or Christian or Shinto or none of the above, whether or not they had ever prayed in their lives, the men all prayed together now as the earth trembled and flashes of light lit up in the hills ahead. In the morning they were to attack.

Few of them slept, despite the long hike. They lay on the cold ground, looking up at the stars and wondering what battle would be like. But they couldn’t know. They couldn’t know that they were about to see and do things that would change them utterly. They couldn’t yet understand that they were about to step off the edge of the world.