Chapter 21

By the time they came down out of the Vosges, the Nisei soldiers were broken in every way that war can break young men. Between May 1943 and November 1944, they had taken 790 casualties—most while rescuing just over two hundred members of the Texas unit. They needed rest. To grieve for lost friends. To come to terms with what they had been through.

They boarded trucks and headed south to take up defensive positions on the French-Italian border. Their official mission was to block the Germans crossing from northern Italy into France, but nobody expected the Germans to make such a move, so there was little chance they would see significant combat.

The army’s intention was to give the Nisei a break, and for many it came just in time. From the Maritime Alps above Nice and Monaco, they had stunning views of a bright-blue Mediterranean Sea and coastline. At sunset, they watched the sea turn purple and the sky blossom orange and violet. They felt safer than they had in a long while, and they slept as they had not slept in months.

They spent their free time roaming up and down the sun-drenched French Riviera, sitting at sidewalk cafés and eating in restaurants with white-linen tablecloths. Kats had his photograph taken in a studio that catered mostly to celebrities and movie stars. Rudy and some friends explored the luxurious bars and high-stakes casinos in Monte Carlo. Fred picked plump oranges from trees overhanging shady lanes.

They all sat in darkened movie theaters, watching American-made films with French subtitles. And, suddenly, to their surprise, they were watching themselves. French movie theaters had begun showing newsreels featuring the rescue of the Lost Battalion. The Nisei were fast becoming celebrities in France. At each showing, the audiences burst into applause then patted the men on the back and shook their hands as they filed out of the theaters.

When on duty, the soldiers spent much of their time on reconnaissance patrols, climbing up and down rocky hillsides or huddled with radios and binoculars in natural caves and concrete fortifications studying German movements across the border in Italy.

Occasionally, Nisei patrols wearing white parkas ran into similarly clad German patrols, and fierce firefights erupted on snowy, windswept mountainsides. Now and then artillery duels broke out, with hundreds of shells flying in both directions. In January alone, six Nisei soldiers were killed and twenty-four were wounded.

Even when up in the mountains, they contrived simple pleasures, staging epic snowball fights and strumming ukuleles as they sat around campfires. Kats cut an oil drum in half, filled it with steaming-hot water heated over a fire, and used it as an ofuro. There he would sit for hours on end, happily soaking in the tub while looking over the blue Mediterranean spread out below him.

By the end of February, it was clear that what they were calling the “Champagne Campaign” was about to end. Sooner or later, they were going to have to go back into heavy combat. They dreaded it. A year before, they couldn’t wait to get into the war. Now they just wanted to go home.

The artillerymen of the 522nd learned that they were to be detached from the 442nd and sent back north to eastern France to join in the final assault on Nazi Germany. Kats, like Sus Ito and George Oiye and most of his artillery buddies, hated to leave this place of relative ease and his many infantry friends. But orders were orders. They packed up their gear and headed north.

A curious air of secrecy hung over infantry’s future. Some feared they would be sent to the South Pacific to enter the war against Japan. A few dared to think they might be going home. Most resigned themselves to uncertainty.

On March 17, they boarded trucks bound for Marseille. It was a lovely spring morning, and they were determined to extract the last ounce of pleasure from their Riviera sojourn. As many of them as could fit climbed onto the roofs of the trucks, and they sat dangling their legs over the edges, strumming guitars and ukuleles, throwing lemon drops to children running alongside.

The mood changed abruptly when they arrived at the waterfront, where enormous gray landing craft awaited them. They were told to strip all unit-identifying marks from their uniforms and equipment. Whatever lay in store for them, the army didn’t want the world to know about it.

General Clark had been impressed when the 442nd fought for him in Italy the previous year. He’d told Pence then, “The courage and determination which the men of the 442nd RCT have displayed during their short time in combat is an inspiration to all.”[62] In the seven months since, especially after learning of their exploits in the Vosges, Clark had been lobbying hard to get the Nisei back.

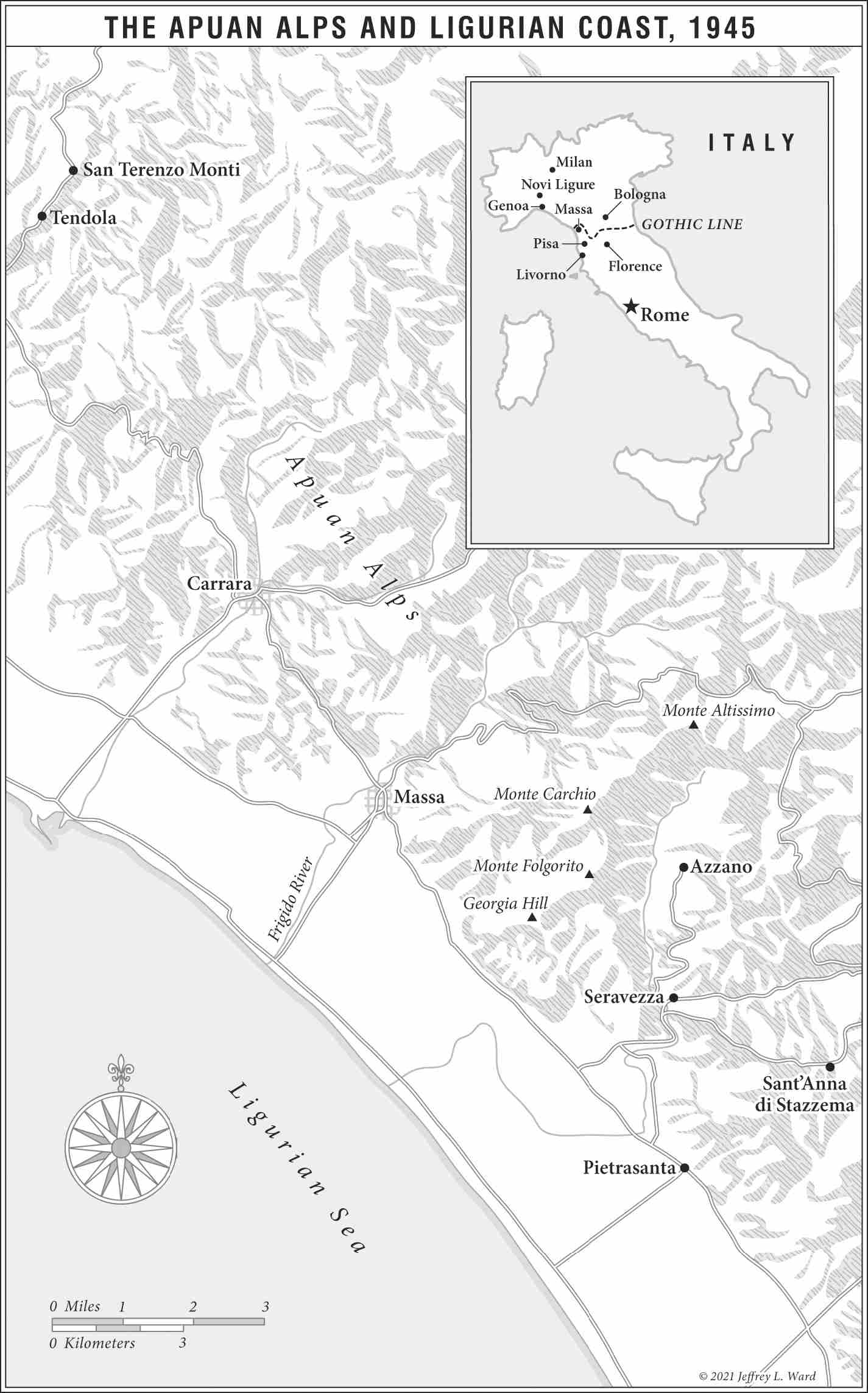

Throughout the fall and winter of 1944, the Allies had hurled themselves repeatedly at a line of German fortifications stretching all the way across Italy, from north of Pisa in the west to the Adriatic Sea in the east. But they had made little headway. As long as the Germans remained entrenched in their mountain caves and concrete bunkers, the Fifth Army was stuck.

Clark wanted to send the Nisei troops against them. And he wanted their presence in Italy to be a surprise to the Germans, who he knew feared them.

He did not expect the 442nd to break through the line. Nobody had been able to do that. But if they pressed hard enough and fought as hard as they had in the Vosges, the Germans would have to shift troops to the west, and that would greatly aid the larger Allied effort.

Neither Fred nor Rudy nor any of the 442nd’s men knew this when they disembarked from their landing craft in the war-ravaged harbor of Livorno in northwestern Italy. All they knew was that they were back in Italy and heading back into combat somewhere up in the mountains.

Over the next several days and nights, they hid in barns by day and traveled in the backs of trucks with blacked-out headlights at night. When they reached the beautiful little town of Pietrasanta, they continued by foot. Fred and Rudy hoisted their gear and fell into a column of K Company men shuffling up a narrow road.

The guys in the 100th headed off in a different direction, disappearing in the darkness.

Someone hissed that the road might be mined and to stay off to one side or the other.

As the road steepened, Fred began to struggle, huffing and puffing, his legs aching. It had been months since they’d been on a real march like this, and he was out of shape.

A little before 4:00 a.m., after five hours of trudging uphill, they arrived in a darkened village called Azzano in the Apuan Alps. The officers quietly rapped on the doors, waking up the villagers, informing them that they had houseguests and telling them to keep their lights turned off.

In small groups, the Nisei soldiers shuffled silently into cellars, barns, and kitchens—anywhere they could be kept out of sight. Sprawled out in hay and on earthen floors, they tried to get some sleep.

In the morning, the villagers offered their guests whatever food they could find in their meager pantries—eggs and cheese and olives, and something the men would remember for the rest of their lives: pancakes made from freshly milled chestnut flour, drizzled with mountain honey.

All day, the Nisei stayed out of sight, knowing that German observers in the surrounding mountains would be keeping an eye on the village. Just before midnight, they tied their dog tags together so they wouldn’t make any sound and rubbed soot on their faces. I and L Companies slipped quietly out into the main street and followed a dark path through the forest into the narrow valley below.

As they crossed a river at the bottom of the valley, they were spotted by two German snipers. A brief firefight erupted, and the Germans were quickly dispatched. Walking single file, each man holding on to the pack of the man in front, they followed an Italian partisan up a steep and rocky footpath on the other side of the valley.

Their mission was audacious: to make what seemed an impossible climb up the nearly vertical mountainside, surprise the Germans from behind, and capture the high ground before morning revealed their presence to enemy observers on nearby peaks.

Well before dawn, after climbing nearly three thousand feet, the first of the soldiers crawled out onto a narrow saddle of land running between the summits of two peaks. With their officers whispering commands, the companies then split into two, each group scrambling across rock ledges to approach one of the two mountain peaks.

L Company came across a cave with unmanned machine guns at its mouth. The guns were pointed at the route they had just safely traveled in the dark.

Private Arthur Yamashita fired a burst from his automatic rifle at the entrance of the cave, and after a few tense minutes seven sleepy Germans crawled out, waving strips of white cloth to signal their surrender.

The gunfire had alerted German sentries in distant observation posts, and now enemy artillery opened fire. The Americans responded with their own artillery fire, and soon the mountains were thundering.

But by the time the sun rose, at 8:00 a.m., the battle for the high ground had been won, and the 442nd had forced open a crack in the Germans’ mountain defenses.

At about the same time as the first Nisei troops reached the top of the mountain from the east, the 100th Battalion attacked from the southwest. As they approached the German perimeter, Company A blundered into a minefield. When the first mine exploded, the men, many of them recent replacement troops, scattered, promptly detonating seven more mines and killing many.

The Germans, alerted by the explosions and the screaming, began raking the confused mass of men with machine-gun fire and tossing down clusters of grenades. Seeing a disaster in the making, some of Company A’s more experienced men ran forward, plunging into the melee.

One of those more experienced men was Rudy’s close buddy, Sadao Munemori. With his men in disarray and bullets whistling past him in the dark, he rallied his men and led them through the minefield, quickly closing to within thirty yards of several entrenched machine-gun nests.

As they neared the German gunners, his men dove for cover behind rocks and in shallow shell craters, but Munemori charged directly at the Germans, hurling grenades and taking out two of the nests. Then, under heavy direct fire, he headed back toward his men. He had nearly made it to the crater where two of his men—Akira Shishido and Jimi Oda—were sheltering when an unexploded grenade bounced off his helmet and rolled toward them. Without hesitating, Munemori dove for the grenade and smothered it with his upper body just as it exploded, killing him instantly but sparing the lives of Shishido and Oda.

On the other side of the mountain, it was K Company’s turn. Following in the footsteps of I and L Companies, Fred and Rudy worked their way down to the river in the valley. The sun was well up now, and the enemy could see their every move.

A squad of Germans concealed in a nearby marble quarry unleashed a barrage of mortars at them, pounding the area with mortar rounds like hailstones in a thunderstorm. There was no place to hide and no place to run. All the men could do was dig in and call for artillery strikes on the marble quarry and the German guns.

Some of the newer, less experienced troops did try to run, leaping to their feet and sprinting upstream or downstream, stumbling over the stones in the river. Fred bellowed at them—“Get down! Get down!”—but panic had set in. Confused, the new men ran directly into a maelstrom of flying shrapnel and shattered stone. Within minutes, three were dead and twenty-three wounded.

Fred, Rudy, and the other surviving members of K Company knew they had to get out of there. Retreat wasn’t an option. The only way lay directly ahead. They rushed forward and began to scale the mountain, hand over foot.

Over the next forty hours, the Nisei fought among the mountain peaks day and night. The operation cost thirty-two Nisei soldiers their lives, with dozens more wounded. But in a little less than two days, the 442nd did what nobody had thought possible. The men opened a gaping hole in the western end of the German defenses. The Allied armies now had a clear route north, and the German army in Italy was all but doomed.

As they withdrew, the Germans continued to rain down shells, and the Americans’ artillerymen pounded them in return. Somewhere between the two, Rudy Tokiwa got caught in the cross fire. Whether it was a German shell or an American round that fell short he never knew, but Rudy was too close when it hit. A dozen jagged pieces of hot shrapnel sliced into his lower body. The wounds weren’t mortal, but they were crippling. For Rudy, the war was over.