Mardi Gras parades through the streets of New Orleans.

New Orleans’s famous “Cities of the Dead” are both impressive and practical. Many believe that traditional underground graves were eschewed due to the city’s high water table. Their similarity to the famed Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris, though, lends credence to some historians’ insistence that the above-ground tombs were merely built in the French and Spanish tradition. Learning the details of the mourning traditions and burial practices (what exactly happens inside those tombs, anyway?) is quite fascinating, so taking a professional cemetery tour is well worth it (and that’s the only way to get into St. Louis No. 1, so be sure to book one in advance). All of these cemeteries are still in use, so keep in mind that these are sacred places, worthy of respect. Marking or otherwise vandalizing tombs, or taking souvenirs, is both insolent and illegal. Also see Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, p 53. This tour crosses town to view both famous and lesser-known cemeteries. A Jazzy Pass (p 165) and a good pair of walking shoes will get you to all of them in a day. START: Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel, 411 N. Rampart St., at the edge of the French Quarter.

❶ ★ Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel and International Shrine of St. Jude. The small chapel was built in 1826 (preceding the more famous and grand St. Louis Cathedral by a quarter century) as a funeral church for the many victims of consecutive yellow fever epidemics. Today, many visitors travel a great distance to pray to Jude, patron saint of hopeless and impossible cases, as a last resort to heal terminal illness. The spooky-cool, candlelit chapel is laden with their prayer placards.  20 min. 411 N. Rampart St. ☎ 504/525-1551. www.judeshrine.com. Donations welcome. Gift shop Mon–Sat 9am–5pm. Masses daily starting at 7am.

20 min. 411 N. Rampart St. ☎ 504/525-1551. www.judeshrine.com. Donations welcome. Gift shop Mon–Sat 9am–5pm. Masses daily starting at 7am.

Our Lady of Guadalupe Chapel.

❷ ★★ St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Opened in 1789 (most of the French Quarter burned the year before), the site is the resting place of such celebrated locals as the city’s first mayor, Etienne de Boré; civil rights pioneer Homer Plessy; New Orleans’s first African-American mayor, Ernest “Dutch” Morial; and world-champion chess player Paul Morphy. The most popular landmark is the Glapion family crypt, where revered (and feared) voodoo priestess Marie Laveau (p 59) was supposedly laid to rest. Some uneducated followers mark her tomb with three small Xs, supposedly so that she will grant them a wish—a false tradition. Needless to say, desecrating any tomb is absolutely forbidden. Visitors allowed in only with a licensed tour guide.  90 min. Conti & Basin sts. ☎ 504/525-3377. www.saveourcemeteries.org. Tour $20 adults, kids 12 and under free. Tours Mon–Sat 10am, 11:30am, 1pm; Sun 10am. Meet at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church (above). Closed holidays.

90 min. Conti & Basin sts. ☎ 504/525-3377. www.saveourcemeteries.org. Tour $20 adults, kids 12 and under free. Tours Mon–Sat 10am, 11:30am, 1pm; Sun 10am. Meet at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church (above). Closed holidays.

Walk 1 block south to Rampart Street; go left for 5 blocks.

Mister Gregory’s. Take a break from the dead and revive with some French press coffee and a decadent pain perdu muffin, gooey with crème Anglaise. Hearty onion soup, salads, croque sandwiches, and all-day breakfasts round out a menu of simple, French-accented goodness. 806 N. Rampart St. www.mistergregorys.com. ☎ 504/407-3780. $. Thurs–Mon 9am–10pm; Tues–Wed 9am–4pm.

Mister Gregory’s. Take a break from the dead and revive with some French press coffee and a decadent pain perdu muffin, gooey with crème Anglaise. Hearty onion soup, salads, croque sandwiches, and all-day breakfasts round out a menu of simple, French-accented goodness. 806 N. Rampart St. www.mistergregorys.com. ☎ 504/407-3780. $. Thurs–Mon 9am–10pm; Tues–Wed 9am–4pm.

Just left of Mister Gregory’s is St. Ann Street. From there, take the #91 bus to St. Louis No. 3.

❹ ★★ St. Louis Cemetery No. 3. Imposing cast-iron gates usher you inside, where you’ll find dramatic angel sculptures and elaborate above-ground tombs for some of the city’s most distinguished Creole families. Established in 1854, the cemetery first opened 1 year after the city’s worst yellow fever epidemic, and filled quickly. Look for tombs of prominent local figures such as legendary Storyville photographer Ernest Bellocq; free person of color and philanthropist Thomy Lafon, who left $600,000 to charity; and architect James Gallier, Jr. He designed the centograph for his tomb, which memorializes his Irish-born architect father, James Gallier, Sr., and his stepmother who perished when their steamship sank on its journey to New Orleans. The active, clean, well-maintained cemetery has a waiting list for burial space.  90 min. See p 65.

90 min. See p 65.

Walk up Esplanade to Carrollton Avenue and take the Canal Streetcar to Canal Street. Transfer to the Cemeteries line, and take it to City Park Avenue. Turn right on City Park Avenue and walk half a block to the entrance to Cypress Grove Cemetery. The entrance to Greenwood, which is visible across the street, is a long block north on Canal Street.

The supposed tomb of Marie Laveau at St. Louis Cemetery No. 1.

❺ ★★ Cypress Grove & Greenwood cemeteries. These neighboring cemeteries were both founded in the mid-1800s by the Firemen’s Charitable and Benevolent Association. Each has some highly original tombs; look for the ones made entirely of iron. Greenwood houses New Orleans’s first Civil War memorial and the tomb of locally beloved, Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist John Kennedy Toole, of A Confederacy of Dunces fame.  1 hr. 120 City Park Ave. and 5200 Canal St.

1 hr. 120 City Park Ave. and 5200 Canal St.

Hoof or taxi it west on City Park Avenue. Go under the expressway, and turn right on Pontchartrain Boulevard toward the next cemetery’s entrance (about 3⁄4 mile).

❻ ★ Lake Lawn Metairie Cemetery. The story goes that Charles T. Howard, a “new money” Yankee, was denied membership at an exclusive racetrack. He exacted revenge by purchasing the property, demolishing the track, and building this opulent, “youthful” graveyard (born in just 1872). Howard’s tomb is here, along with such notables as bandleader Louis Prima; Popeye’s Chicken fast-food chain founder Al Copeland; and Ruth Fertel of Ruth’s Chris Steak House (whose marble edifice oddly resembles a piece of beef). Don’t miss the pyramid-and-sphinx Brunswig mausoleum, the “ruined castle” Egan family tomb, and the Morales tomb. The former resting place of Storyville madam Josie Arlington has a statue of a girl knocking on a door—a virgin being turned away from Josie’s brothel, some said, as Madam Josie would despoil none. The custom crypt was sold and her body moved when either it became a tourist attraction, or blue-blood families complained at having to “mix” with someone of Josie’s ilk. Pick your explanation.  90 min. 5100 Pontchartrain Blvd. ☎ 504/486-6331. www.lakelawnmetairie.com. Free admission. Daily 9am–4pm. Closed holidays.

90 min. 5100 Pontchartrain Blvd. ☎ 504/486-6331. www.lakelawnmetairie.com. Free admission. Daily 9am–4pm. Closed holidays.

Double-back toward Greenwood. At Canal Street and City Park Avenue, continue a half-mile, or take the #27 or #60 bus east on City Park for two stops to Conti Street. Cross City Park Avenue and turn on tiny Rosedale Drive (across from Burger King, next to Delgado Community College).

Monument in Greenwood Cemetery.

❼ ★★ Holt Cemetery. For the more intrepid (and truly cemetery-obsessed), this lesser-known graveyard is worth seeking out. Dating to the mid-1800s, this former burial ground for indigents has nearly all in-ground graves—unusual for New Orleans. They are maintained to varying degrees by the families, which results in its particular, folk-art appeal, with hand-drawn markers and family memorabilia scattered about. It’s incredibly picturesque and poignant in its own way.  30 min. 635 City Park Ave. Mon–Fri 8am–2:30pm, Sat 8am–noon.

30 min. 635 City Park Ave. Mon–Fri 8am–2:30pm, Sat 8am–noon.

New Orleans is renowned for its lack of moderation. Its literary history—laden with both luminaries and lesser-knowns—follows the pattern. For centuries, notable writers have been drawn to the city, where freedom of thought (and action) have always been revered; where the colorful history, eccentric characters, and sensual charms inspire ideation; and where the city’s contrasts—beauty and decay, rich and poor—kick-start the imagination. This leisurely walking tour of the French Quarter highlights a few literary hot spots. START: 800 Iberville St.

❶ Ignatius J. Reilly statue. John Kennedy Toole’s New Orleans–set novel A Confederacy of Dunces went unseen until 11 years after his 1969 suicide. His mother tirelessly shopped the manuscript. It was finally published—and won a Pulitzer Prize. Some believe that the idiosyncratic Ignatius, the indolent, urbane protagonist immortalized here, epitomizes many a French Quarter character. 800 Iberville St.

Walk down Iberville Street to Royal Street and turn left.

Ignatius J. Reilly statue.

❷ ★★ Hotel Monteleone. The venerable hotel is ground zero of New Orleans’ literati. The lengthy list of legends who stayed, wrote, and/or drank here includes Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Tennessee Williams, Anne Rice, Eudora Welty, Richard Ford, Winston Groom, and John Grisham. Truman Capote was nearly born in a suite here (a late change of plans resulted in a nearby hospital birth, to Tru’s eternal disappointment). Check out the display of famous books penned herein (just inside the front doors as you enter the glorious lobby), and try a classic cocktail on the slow-turning Carousel bar (p 141). 214 Royal St.

Continue up Royal Street to St. Louis Street and turn left.

★★ Antoine’s. One of the first fine-dining restaurants in the New World, it’s been owned and operated by the same family for an astonishing 175 years, during which the hoi polloi of New Orleans society, plus countless celebrities, have slurped down oysters Rockefeller (invented here) and partied down in the many private rooms. With its crisp, white-jacketed waitstaff and French-based cuisine, it’s as classic as New Orleans gets. It’s also a central character in Dinner at Antoine’s, Frances Parkinson Keyes’s best-selling murder mystery of 1948. 713 St. Louis St. www.antoines.com. ☎ 504/581-4422. $$.

★★ Antoine’s. One of the first fine-dining restaurants in the New World, it’s been owned and operated by the same family for an astonishing 175 years, during which the hoi polloi of New Orleans society, plus countless celebrities, have slurped down oysters Rockefeller (invented here) and partied down in the many private rooms. With its crisp, white-jacketed waitstaff and French-based cuisine, it’s as classic as New Orleans gets. It’s also a central character in Dinner at Antoine’s, Frances Parkinson Keyes’s best-selling murder mystery of 1948. 713 St. Louis St. www.antoines.com. ☎ 504/581-4422. $$.

Go back to Royal Street and turn left. Walk 2 blocks to St. Peter Street.

❹ Le Monnier Mansion. In addition to its architectural significance as the first four-story building, this “skyscraper” looms large in the city’s literary history. George Washington Cable lived and set his 1873 story, “Sieur George” here; John and Lou Webb published works by William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Henry Miller, Allen Ginsberg, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti in their pioneering Outsider journal, as well as the first book of a young poet named Charles Bukowski. 640 Royal St., at the corner of St. Peter St.

Continue up Royal Street 1 block to Orleans Street and turn left.

❺ Bourbon Orleans Hotel. Site of the famous quadroon balls, where wealthy white men were introduced to potential mistresses: free women (and girls) of color who were one-fourth black (quadroon). The men negotiated placage arrangements with the young women’s mothers, covering financial, educational, housing, and child support for the mistresses. Accounts of this unusual but accepted custom appear in many books, notably Anne Rice’s The Feast of All Saints, Isabel Allende’s Island Beneath the Sea, and Old Creole Days by George Washington Cable. 717 Orleans Ave.

Turn back down Orleans Street and cross Royal Street to Pirate’s Alley.

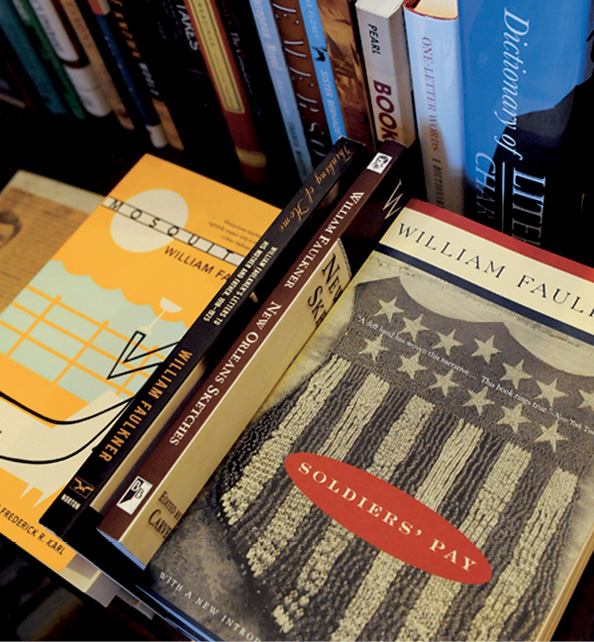

Books by William Faulkner on sale at Faulkner House Books.

❻ ★★★ The Faulkner House. William Faulkner, Nobel and Pulitzer Prize–winning author and true literary icon, wrote his debut novel, Soldiers’ Pay, here. Faulkner lived, wrote, and entertained here during the height of French Quarter bohemia in the 1920s, when New Orleans’s decadent ways attracted a steady influx of artists and writers. The pioneering current owners—themselves central figures on the area’s literary scene—have lovingly restored this stunning 1840 town house, turning the first floor into one of the premier independent bookstores in the country: the tiny, perfect, Faulkner House Books. An elegantly curated collection of first editions, rarities, and contemporary literature adorns the floor-to-ceiling shelves of this petite gem.  30 min. 624 Pirate’s Alley. Bookstore: ☎ 504/524-2940. www.faulknerhousebooks.com or www.wordsandmusic.org. Free admission. Bookstore daily 10am–5:30pm. Closed Mardi Gras day.

30 min. 624 Pirate’s Alley. Bookstore: ☎ 504/524-2940. www.faulknerhousebooks.com or www.wordsandmusic.org. Free admission. Bookstore daily 10am–5:30pm. Closed Mardi Gras day.

Back on Royal Street, return to St. Peter Street and turn left.

❼ ★ Tennessee Williams House. Despite the (pen) name, Tennessee Williams may be the literary figure most closely associated with New Orleans, which the native Missourian considered his spiritual home. About A Streetcar Named Desire, which he wrote from an attic room here in 1946, Williams said that he could hear “that rattle trap streetcar named Desire running along Royal and the one named Cemeteries running along Canal, and it seemed the perfect metaphor for the human condition.” 632 St. Peter St. No public admission.

New Orleans has inspired many to pick up the pen, and perhaps it will inspire you to pick up a book or three. Once you’ve conquered Anne Rice’s fangtastic modern horror classic Interview with the Vampire, try John Kennedy Toole’s offbeat, Pulitzer Prize–winning A Confederacy of Dunces, or one of James Lee Burke’s page-turners featuring Cajun crime-buster Dave Robicheaux. The Tennessee Williams drama A Streetcar Named Desire captures the city’s boozy, sweaty malaise like none other, while George Washington Cable’s Old Creole Days poked fun at NOLA life circa 1879. For non-fiction, start with Ned Sublette’s fascinating The World That Made New Orleans and work your way up to Gary Krist’s Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans. Katrina spawned brilliant, moving analyses and memoirs, including Why New Orleans Matters by Tom Piazza and Dan Baum’s Nine Lives. For dessert, feast on Sara Roahen’s delightful Gumbo Tales: Finding My Place at the New Orleans Table.

❽ Victor David House. In 1838, wealthy merchant Victor David built this exquisite example of sophisticated Greek Revival styling. Nearly a century later, historian-novelist Grace King purchased the property to serve as headquarters for Le Petit Salon, an influential ladies’ club whose purpose was to preserve New Orleans and French Quarter culture. Combined with next door’s Le Petit Théâtre du Vieux Carré (founded in 1916), this was a powerfully influential literary block. 620 St. Peter St. No public admission.

Pontalba Apartments.

❾ ★★ Pontalba Apartments. Among the mid-1920s New Orleans salons, perhaps none was so soignée (if short-lived) than that of Sherwood Anderson. Somerset Maugham, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Carl Sandburg, William Faulkner (whom Anderson mentored), and others congregated in the Pontalba parlor overlooking beautiful Jackson Square. Some of the works that appeared in the influential Double Dealer literary journal likely originated here. The Dealer, founded to promote the oft-maligned Southern culture, brought acclaim to the emergent American modernist literary movement and gave rise to the Southern Review. 540-B St. Peter St.

Mardi Gras—the biggest free party in North America—is New Orleans’s most popular event, for good reason: the creativity, crowds, and camaraderie—not to mention the music, marching, and general merriment—and the memories you’ll make. Despite the reputation, it’s much more than a spring break–style drunkfest. It’s a family event for locals and a celebration of traditions new and old, with religious origins: the old idea of good Christians massively indulging prior to their impending self-denial during Lent, the day after Mardi Gras. New Orleans’s event dates to 1743. By the mid-1800s, the elite “krewes” (groups of prominent society and business types) embraced it as the height of their social season. Today, those old-line (desegregated, finally) krewes and dozens of new ones keep the traditions, spectacle, hilarity, and subversion going. The largest parades have dozens of floats, celebrity guests, bands, dance troupes, scooter squads, and thousands of participants. You bring the rollicking, party-ready attitude; New Orleans does the rest.

Below are recommended events for Lundi Gras (Mon) and Mardi Gras (Tues); citywide parades roll nearly every day in the 2 weeks prior to Mardi Gras day.

A float from the Zulu Aid and Pleasure Club.

Lundi Gras (Monday)

❶ ★★ Zulu Lundi Gras Festival. Here’s your opportunity to get a little pre-parade festing in—with three stages of music plus food and drinks along the riverfront, sponsored by Zulu. The big event comes around 5pm when the Zulu and Rex krewe kings arrive, welcomed by the mayor, who proclaims the official start of Mardi Gras. Afterward you can hightail it to the nearby part of the parade route on Canal Street to catch the Proteus parade (starts at 5:15pm), followed by Orpheus (see below). www.lundigrasfestival.com. Woldenberg Park. Lundi Gras (Mon). 10am–6:30pm.

❷ ★★★ Orpheus. Native New Orleanian Harry Connick, Jr.’s newish (1993) superkrewe boasts more than 1,200 men and women on 30 megafloats, throwing beads, pearls, silver doubloons, plush ducks, go-cups, and more. Celebrity guests serving as “royalty” have included Whoopi Goldberg, Sandra Bullock, Stevie Wonder, Quentin Tarantino, Dan Aykroyd, and James Brown, the “Godfather of Soul.” www.kreweoforpheus.com. Starts uptown at Napoleon Ave. and Tchoupitoulas St. and ends downtown at the Convention Center. Lundi Gras (Mon). Begins 6pm.

Mardi Gras Day Parades

❸ ★★★ Zulu. The premier African-American parade was originally created to parody haughty, race-restricted Rex. Now desegregated (both krewes welcome all members), Zulu riders still wear ironic attire like blackface and grass skirts. As the 35 floats and 1,200 riders pass, look for the famed Witch Doctor and Big Shot floats, and especially the prized Zulu coconuts: hand-painted souvenirs that even the natives scramble for. Hang out near the cops keeping the crowds in check; Zulu members typically pass coconuts to them as thanks. www.kreweofzulu.com. Starts uptown at Jackson and Claiborne aves. and ends at Orleans Ave. and N. Broad St. Mardi Gras (Tues). Begins 8am.

Prepping for Parade Mania

Arthur Hardy’s Mardi Gras Guide is the unofficial Mardi Gras bible, from Twelfth Night (Jan 6, the official start of the Carnival season) through fat Tuesday, it covers the all-important parade schedule and includes a calendar of related events and informative articles on Carnival history. It’s available all over the city—in bookstores, souvenir stores, groceries. You can also order an advance copy at www.arthurhardy.com and download the app, which includes the very useful parade tracker.

❹ ★★★ Society of St. Anne. Across town in the Bywater neighborhood, the bohemian Society of St. Anne musters around 10am. This fantastical walking club (no floats) is known for its madcap, au courant, sometimes risqué costumes and always wildly creative revelers. Due to overlapping timing, you’ll have to make the tough choice between seeing this group and the Zulu parade. Starts at Piety and Burgundy sts. Follows an unspecified route through Marigny and French Quarter, usually along Royal St. Ends at Canal St. Begins approx. 10am.

Want plenty of parade throws? On Mardi Gras day, “masking” (coming in costume) is essential. Definitely participate in some way, whether simple or outrageous. Yell the traditional phrase, “Throw me something, mister!” to show some Mardi Gras spirit. (And no, you needn’t—and shouldn’t—show skin. Save that for Bourbon Street, which doesn’t have parades.) Bring a bag to haul your loot—bead lust is contagious—and share the bounty with neighbors—there’s plenty, and it’s part of the fun (well, nobody shares the highly coveted coconuts from Zulu or shoes from Muses). Bring some starter snacks and beverages to be safe, though vendors usually walk the parade routes, and toilet paper for the rare and well-trafficked portolets.

❺ ★★ Rex. The King of Rex is also the King of Carnival, so this—the oldest parade (it debuted in 1872)—is the big kahuna. The royal costumes are a sight to behold—lots of glittery gold (and purple and green—they created the time-honored color combo, after all). The throws are fairly traditional, but every float’s is different. www.rexorganization.com. Starts uptown at S. Claiborne and Napoleon aves. and ends downtown at Canal and South Peter sts. Mardi Gras (Tues). Begins 10am.

A crowd pleading and competing for “throws” from a passing float.

❻ ★  Between and After the Parades. Families and kids ride their self-decorated “truck floats” and toss out toys and trinkets; pro-level high school marching bands make a mighty, precision sound; elegant flambeaux (torch-bearers) harken back to days of pre-electricity; and themed walking clubs range from nice to naughty to nutty. Some parade watchers go home after the “official” end of Mardi Gras with the passing of Rex, but these are almost (or even more) popular, the “true” closing parades, and very worth hanging around for. Elks and Crescent City truck parades start uptown at S. Claiborne and Napoleon aves. and end in Mid-City at Tulane Ave. and S. Robertson St. Follows Rex.

Between and After the Parades. Families and kids ride their self-decorated “truck floats” and toss out toys and trinkets; pro-level high school marching bands make a mighty, precision sound; elegant flambeaux (torch-bearers) harken back to days of pre-electricity; and themed walking clubs range from nice to naughty to nutty. Some parade watchers go home after the “official” end of Mardi Gras with the passing of Rex, but these are almost (or even more) popular, the “true” closing parades, and very worth hanging around for. Elks and Crescent City truck parades start uptown at S. Claiborne and Napoleon aves. and end in Mid-City at Tulane Ave. and S. Robertson St. Follows Rex.

This tour visits key touchstones from the only true American musical form: jazz. When the cultural influences of two continents—Africa and Europe—collided in New Orleans, their energy and essences began to stew. Drums met horns and intertwined with keys and strings. When the rhythmic spice of the Caribbean and the emotions of societal circumstances were mixed in, a powerful musical brew began to bubble up. Add a dollop of time, a bit of brilliance, and something indefinable, and we got jazz. Amazingly, it all happened right here, along this path. START: 840 N. Rampart St.

❶ ★ Clothes Spin Laundromat. Without jazz, there would be no rhythm and blues, no rock ’n’ roll. This unassuming washeteria is surely the only laundromat that is also a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame landmark. It was the legendary recording studio of producer Cosimo Matassa, opening in 1945 as jazz was swinging and morphing into new musical forms. Arguably the first rock-and-roll record, Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti,” was cut here, as were an astounding streak of influential hits by Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Ray Charles, Irma Thomas, Sam Cooke, and gobs more. Check out the memorabilia displayed above the dryers in back. 840 N. Rampart St.

Go 2 blocks south on Rampart Street to St. Peter Street.

Maison Bourbon.

❷ ★ Congo Square. This hallowed cultural ground (inside Armstrong Park in the Faubourg Tremé, the historic African-American neighborhood and “musical incubator”; see p 40) is widely recognized as the place where jazz began. Beginning in 1817, Napoleonic law (which still holds sway in Louisiana) and the Code Noir (Black Code) governing the treatment of slaves gave them Sundays off. They gathered here, creating a marketplace, a social scene, and a place to practice their Voodoo and Christian religions through prayer, drumming, chanting, and dancing. The movements, rhythms, and instruments of Africa joined those of the Creoles of Haiti, Spain, and France. These energetic festivities became more performance-oriented and eventually drew white onlookers and followers; it’s said that madams from nearby brothels came to hire performers to entertain at their houses. As interest spread and the sound transformed, new forms emerged, giving rise to jazz and a musical transformation that swept the world. Inside Armstrong Park at N. Rampart and St. Peter sts.

Walk uptown 1 block to Toulouse Street and turn left. Go 2 blocks and turn right at Dauphine Street.

Jazz Clubs

Jazz (and all its modern offspring) still thrives in New Orleans. Now that you’ve seen some touchstones, it’s time to hear the real thing—and maybe shake a tail feather or cut a rug. Try one of these clubs (see also Chapter 7):

•Fritzel’s (p 118), 733 Bourbon St.

•Irvin Mayfield’s Jazz Playhouse (p 118), 300 Bourbon St.

•Little Gem Saloon (p 119), 445 S. Rampart St.

•Old U.S. Mint (p 51), 400 Esplanade Ave.

•Palm Court Jazz Café (p 119), 1204 Decatur St.

•Preservation Hall (p 119), 726 St. Peter St.

•Snug Harbor (p 118), 626 Frenchmen St.

❸ May Baily’s Place & Storyville. This bar in the Dauphine Orleans Hotel is one of the few remnants of Storyville, the 16-block legalized red-light district based on and around nearby Basin Street. As the framed 1857 license hanging in the bar proves, May Baily’s was a licensed house of ill repute (actually pre-dating Storyville, which thrived from 1898–1917). Hired musicians entertaining bordello guests helped to popularize jazz. The good times came to an abrupt end in 1917 when, at the Navy’s behest, the city shut down Storyville “in an effort to curb vice because of the proximity of armed service personnel.” But the swinging new sound was just beginning. 415 Dauphine St.

Continue along Dauphine Street; turn right on Canal Street to Rampart Street. (Note the fabu-lously renovated Saenger Theatre [see p 131], one of several old theaters recently renovated to all-new awesomeness.) Cross Canal Street and continue south along Rampart Street for 4 blocks.

Harry Connick, Jr. and Branford Marsalis take the stage at Jazz Fest.

Jazz Fest: Laissez les bon temps roulez!

What began in 1969 as a small gathering in Congo Square to celebrate the music of New Orleans has become a world-renowned phenomenon that ranks as one of the most respected, musically comprehensive events anywhere—and a heck of a good time. For two consecutive long weekends in late April and early May, New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival by Shell (the official name) turns the Fair Grounds Race Course into a mega-party. Nicknamed “Fest” or Jazz Fest, that hardly represents its scope, which spans alternative rock, Delta blues, hip hop, gospel, and Cajun folk (and yes, jazz in many forms) on 13 stages. Fest attracts superstars like Bruce Springsteen, Stevie Wonder, Lady Gaga, and Pearl Jam, yet the local and unknown acts are often the most rewarding. What elevates Fest is the “Heritage” part: It brings the NOLA. The food, art, and cultural exhibits are simply superb. If you come (and you should), book your hotel, flight, restaurant reservations, and nighttime show tickets early—months or up to a year out. That’s before the bookings are announced, but the leap of faith will pay off. Info at New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival (1205 N. Rampart St.; ☎ 504/558-6100; www.nojazzfest.com).

❹ ★ Backatown. Serious jazz worshipers make a pilgrimage to this area, one of several called “Backatown” (from “back of town”). It’s not much to look at besides boarded-up old buildings, yet it is perhaps the most significant block in American music history. The roots of jazz first grew out of Congo Square. But the Smithsonian considers the Eagle Saloon and third-floor Odd Fellows Hall (401 S. Rampart St.) to be “The Birthplace of Jazz,” for the pioneers who played here: greats like Buddy Bolden, Jelly Roll Morton, and King Oliver. Although dilapidated now, hopes run high to turn the Eagle Saloon into the New Orleans Music Hall of Fame. At the Iroquois Theater (413–415 S. Rampart St.), many musicians got their starts accompanying silent films and stage acts. A young Louis Armstrong won a talent contest there after buying his first cornet with money earned at the Karnofsky Tailor Shop (427–431 S. Rampart St.). The shop, now listed in the National Register of Historic Places, was owned by a white, Jewish family who raised and mentored a young Armstrong. 400 block of S. Rampart St.

Little Gem Saloon.

★★ Little Gem Saloon. Here at Frank Douroux’s Little Gem Saloon, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club frequently started and ended its jazz funerals, and the greats also performed. After being shuttered and neglected for 40 years, the spiffed-up club re-opened in 2012, showcasing great live jazz in this area once again. Gulf oysters, cocktails, and Southern soul food should satisfy any hunger or thirst in your party. 445 S. Rampart St. www.littlegemsaloon.com. ☎ 504/267-4863. $$.

★★ Little Gem Saloon. Here at Frank Douroux’s Little Gem Saloon, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club frequently started and ended its jazz funerals, and the greats also performed. After being shuttered and neglected for 40 years, the spiffed-up club re-opened in 2012, showcasing great live jazz in this area once again. Gulf oysters, cocktails, and Southern soul food should satisfy any hunger or thirst in your party. 445 S. Rampart St. www.littlegemsaloon.com. ☎ 504/267-4863. $$.

Today’s vibrant Arts District was once a shabby industrial collection of abandoned warehouses. Thanks to adaptive reuse, this once-rundown area has been transformed into a happening neighborhood, jammed with spacious museums showcasing Southern art, history, and heritage. The revitalization has spawned a fine gallery scene along Julia Street (stroll the 300–700 blocks), and given new life—and unified purpose—to an old neighborhood. START: If you’re in the Central Business District, it’s an easy walk. Alternately, take the St. Charles streetcar to St. Joseph Street. Then walk east 2 blocks to Camp Street. Turn right and walk 1 block, past the Ogden Museum.

❶ ★★★ Civil War Museum at Confederate Memorial Hall. Here is the Confederate flag, that hot-button epicenter of controversy, displayed sans judgment. It’s simply part of the second-largest collection of relics in the U.S., including documents, weapons, uniforms, portraits, and the personal effects of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee. The unusual 1891 pressed-brick Romanesque building is itself stunning, while an Alabama Legion battle flag with 83 painstakingly mended bullet holes is a moving reminder of this gruesome war.  30–60 min. 929 Camp St. ☎ 504/523-4522. www.confederatemuseum.com. Admission $8 adults, $5 children 7–14, free for children 6 and under. Thurs–Sat 10am–4pm.

30–60 min. 929 Camp St. ☎ 504/523-4522. www.confederatemuseum.com. Admission $8 adults, $5 children 7–14, free for children 6 and under. Thurs–Sat 10am–4pm.

❷ ★★ Ogden Museum of Southern Art. In this dazzling modern building, galleries surrounding a soaring, glass-faced atrium house the premier collection of Southern art in the United States, by artists from 1890 to today. We particularly like the permanent exhibit of self-taught and outsider art, including some locals. If you go on a Thursday, Ogden After Hours presents live music in another gorgeous, wood-ceilinged anteroom. We’re also keen on the well-curated gift shop, with its consistently covetable, artsy souvenirs.  1–2 hr. 925 Camp St. ☎ 504/539-9650. www.ogdenmuseum.org. Admission $13.50 adults, $11 students/seniors, $7.25 children 5–17, free for children 4 and under. Wed–Mon 10am–5pm, live music Thurs 6–8pm.

1–2 hr. 925 Camp St. ☎ 504/539-9650. www.ogdenmuseum.org. Admission $13.50 adults, $11 students/seniors, $7.25 children 5–17, free for children 4 and under. Wed–Mon 10am–5pm, live music Thurs 6–8pm.

Live music is on hand at the Ogden’s annual White Linen Night.

❸ ★ Contemporary Arts Center. The CAC has three stories of airy galleries and (usually) a provocative, large-scale installation showing in the street-level windows. Modern art fans gather here for interesting, experimental, and sometimes influential work in various mediums, including theater, dance, music, and film.  1 hr. 900 Camp St. ☎ 504/528-3800. www.cacno.org. Admission $10 adults, $8 college students/seniors; free to children and students through grade 12. Wed–Mon 11am–5pm.

1 hr. 900 Camp St. ☎ 504/528-3800. www.cacno.org. Admission $10 adults, $8 college students/seniors; free to children and students through grade 12. Wed–Mon 11am–5pm.

Return south along Camp Street 1 block to Andrew Higgins Drive and turn left. Go 1 block to Magazine Street.

❹ ★★★ National World War II Museum. This must-see, world-class facility boasts an abundant collection of artifacts, stellar videos, and plenty of advanced interactivity. Yet it still emphasizes the personal side of war, highlighted by veteran volunteers on site and incredibly moving audio and video of civilians and soldiers recounting their first-hand experiences. Founded by the late historian and best-selling author Stephen Ambrose (author of Band of Brothers and a consultant to the film Saving Private Ryan), the museum now spans 6 acres and multiple themed buildings. Additionally, there are kicky, USO-style shows in the BB’s Stage Door Canteen; a “4D” multisensory film, Beyond All Boundaries; and a pretty realistic mock submarine battle aboard Final Mission: The USS Tang Experience.  2–3 hr. 945 Magazine St. ☎ 504/527-6012 or 504/528-1944. www.nationalww2museum.org. Admission $24 adults, $20.50 seniors, $14.50 students/active military, free for children 4 and under and World War II veterans; separate admission for Beyond All Boundaries and Final Mission. Daily 9am–5pm. Closed holidays.

2–3 hr. 945 Magazine St. ☎ 504/527-6012 or 504/528-1944. www.nationalww2museum.org. Admission $24 adults, $20.50 seniors, $14.50 students/active military, free for children 4 and under and World War II veterans; separate admission for Beyond All Boundaries and Final Mission. Daily 9am–5pm. Closed holidays.

Back on Andrew Higgins Drive, go east 2 blocks to Tchoupitoulas Street.

A muffuletta at Cochon Butcher.

★★★ Cochon Butcher. Squeamish, be warned: They do butcher hogs here. But excellent house-smoked meats and sausages will rock the carnivore’s world. The pork belly sandwich with cucumber and mint is wondrous; the heated muffuletta rivals (maybe even bests?) more famous versions. Get the dreamy mac and cheese and swoonful caramel doberge cake too. 930 Tchoupitoulas St. ☎ 504/588-7675. www.cochonbutcher.com. $.

★★★ Cochon Butcher. Squeamish, be warned: They do butcher hogs here. But excellent house-smoked meats and sausages will rock the carnivore’s world. The pork belly sandwich with cucumber and mint is wondrous; the heated muffuletta rivals (maybe even bests?) more famous versions. Get the dreamy mac and cheese and swoonful caramel doberge cake too. 930 Tchoupitoulas St. ☎ 504/588-7675. www.cochonbutcher.com. $.

New Orleans’s art scene—or scenes, more accurately—thrives well beyond the Arts District. There’s great gallery browsing along all of Royal Street in the French Quarter and an edgy arts scene scattered along St. Claude Avenue (www.facebook.com/SCADNOLA). These museums, located elsewhere in the city, are also terrific:

•Backstreet Cultural Museum (p 42), 1116 Henriette Delille St.

•Besthoff Sculpture Garden (p 83), 1 Collins Diboll Circle.

•McKenna Museum of African-American Art, 2003 Carondelet St.

•New Orleans Museum of Art (p 14), 1 Collins Diboll Circle.

•New Orleans Pharmacy Museum (p 10), 514 Chartres St.

•Southern Food & Beverage Museum, 1504 Oretha Castle Haley Blvd.

Go north 2 blocks on Tchoupitoulas Street to Julia Street and turn left.

❻ ★★★ Louisiana Children’s Museum. This fully interactive museum is more like a playground-meets-summer camp-meets-laboratory, in disguise. It’ll keep kids occupied for a few hours. Along with changing exhibits, the museum offers art projects; all sorts of mini-scenarios in which to play, shop, experiment, climb, and build; a chance to “build” a New Orleans–style home; and lots of activities exploring music, fitness, science, and life itself.  11⁄2–2 hr. 420 Julia St. ☎ 504/523-1357. www.lcm.org. Admission $8.50, children under 1 free. Sept–May Tues–Sat 9:30am–4:30pm, Sun noon–4:30pm; June–Aug closing time is 5pm. Kids 15 and under must be accompanied by an adult. Closed major holidays.

11⁄2–2 hr. 420 Julia St. ☎ 504/523-1357. www.lcm.org. Admission $8.50, children under 1 free. Sept–May Tues–Sat 9:30am–4:30pm, Sun noon–4:30pm; June–Aug closing time is 5pm. Kids 15 and under must be accompanied by an adult. Closed major holidays.

Cooking demonstration at the Southern Food & Beverage Museum.

Across Rampart Street from the French Quarter and a world away, the Faubourg Tremé was unusual from its 1730s inception. Claude Tremé, a Frenchman whose wife’s family owned the land, began selling off lots to working-class Creoles and free people of color. Under French laws then governing Louisiana, they could own property. Thus, it is the country’s oldest African-American community. It grew into a tight-knit, educated, and highly empowered community recognized for artistic progressiveness—not just in jazz and brass bands, as is well-known but also in fine arts, poetry, and literature. Recently popularized (and subsequently gentrified) thanks to HBO’s post-Katrina series named for the area, the Tremé is a civil rights touchstone and still a massively influential and productive cultural incubator. Once considered unsafe for tourists, the Tremé is vastly improved. But crime persists, as in many parts of the city, so explore with a pal and heed your spidey sense. START: Inside Armstrong Park at N. Rampart at St. Peter streets.

❶ ★★ Congo Square. This supremely significant corner of what is now Armstrong Park was where African- and Haitian-born slaves and Creole free men of color were permitted to mingle, trade goods, worship, dance, drum, and create sounds that went on to give rise to a thing called jazz. See p 33 Rampart and St. Peter sts, inside Armstrong Park.

Walk through Armstrong Park toward the Mahalia Jackson Theater.

❷ ★ Armstrong Park. After families were displaced to clear the land for this park, it lay fallow for years. Later, the park was a haven for crime and drug users. It has finally emerged as a community point of pride, after extensive rehabbing, with activities, a sculpture garden, and the grand Mahalia Jackson Theater. 901 N. Rampart St. Park open daily 8am–6pm (‘til 7pm during daylight savings).

Take the walkway to the right of Mahalia Jackson Theater, and exit the park onto St. Philip Street. Turn left, walk up St. Philip Street for 2 blocks, and go left on Robertson Street.

Walking tour of Armstrong Park.

❸ ★★ Candlelight Lounge. Among the last of the great live music clubs—or perhaps the first of a new crop given the neighborhood’s current energy. Wednesday nights when the Tremé Brass Band plays, it’s the place to be. That’s them on the mural. 925 North Robertson St. ☎ 504/525-4748. Hours and cover charges vary. Tremé Brass Band plays most Wednesdays around 9:30pm, $10–$20 cover.

Head back on Robertson Street, crossing St. Philip Street and continuing for 3 blocks to Esplanade Avenue.

Lil’ Dizzy’s. This local diner is a gathering place for movers, shakers, neighbors, and nobodies, as much for the neighborhood lowdown as for the divine trout Baquet and stellar fried chicken. 1500 Esplanade Ave. ☎ 504/569-8997. www.lildizzyscafe.net. Mon–Sat 7am–2pm; Sun 8am–2pm. $$.

Lil’ Dizzy’s. This local diner is a gathering place for movers, shakers, neighbors, and nobodies, as much for the neighborhood lowdown as for the divine trout Baquet and stellar fried chicken. 1500 Esplanade Ave. ☎ 504/569-8997. www.lildizzyscafe.net. Mon–Sat 7am–2pm; Sun 8am–2pm. $$.

Take Esplanade Avenue 1 block south to Villere Street and turn right. Then take a left on Governor Nicholls Street.

❺ New Orleans African American Museum of Art, Culture and History. Although it is currently closed for renovations, this important center set in a lovely 1820s Creole villa is dedicated to protecting and promoting African-American history. We eagerly anticipate its reopening. 1418 Governor Nicholls St. www.noaam.org.

Walk 11⁄2 blocks down Governor Nicholls Street to Tremé Street and jog left.

❻ Location from HBO’s Tremé. The highly lauded HBO series Tremé, which ran from 2010 to 2014, went to great lengths to show the “real” New Orleans. It featured many local musicians, traditions, and locations, including this one, home of D.J. Davis McAlary (played by Steve Zahn). 1212–1216 Tremé St.

Head back to Governor Nicholls Street and turn left.

Mardi Gras Indians at the Backstreet Museum.

❼ ★★ St. Augustine Church. Built in 1841 largely by blacks and free people of color, this was the first Catholic church to integrate African Americans and whites, at a time when they simply did not mix. After Katrina, the neighborhood and beyond successfully fought to save the church from closure by the Archdiocese. Don’t miss the poignant Tomb of Unknown Slave (outside, facing Gov. Nicholls St.). The cross of chains draped with shackles honors slaves buried in unmarked graves. 1210 Gov. Nicholls St. (enter on Henriette Delille at Tremé St.). ☎ 504/525-5934. www.staugchurch.org. Sunday Jazz Mass 10am.

From the front entrance to the church, cross Henriette Delille Street and turn right.

❽ ★★★ Backstreet Cultural Museum. Owner Francis Sylvester displays his fascinating and essential collection of the cultural icons unique to this neighborhood: brass bands, jazz funerals, social aid and pleasure clubs, and especially Mardi Gras Indians.  60 min. 1116 Henriette Delille St. ☎ 504/522-4806. www.backstreetmuseum.org. Admission $10. Tues–Sat 10am–4pm. •

60 min. 1116 Henriette Delille St. ☎ 504/522-4806. www.backstreetmuseum.org. Admission $10. Tues–Sat 10am–4pm. •