The credit system accelerates the material development of the productive forces and the establishment of the world market.

—MARX

On the morning of December 2, 1851, Emile Pereire hurried to the house of James Rothschild to reassure the bedridden banker that all had gone smoothly with the coup d’état. The story of their subsequent break and awesome struggle, which lasted until the Pereire brothers’ downfall a year before James died in 1868, is one of the legendary battles of high finance. It became the subject much later of Zola’s novel L’Argent (Money).1 Behind it lay two quite different conceptions of the role of money and finance in economic development. The haute banque of the Rothschilds was a family affair—private and confidential, working with opulent friends without publicity, and deeply conservative in its approach to money, a conservatism expressed through attachment to gold as the real money form, the true measure of value. And that attachment had served Rothschild well. He remained, as a worker publication of 1848 complained, “strong in the face of young republics” and a “power independent of old dynasties.” “You are more than a man of state. You are the symbol of credit.” The Pereires, for their part, schooled in Saint-Simonian ways of thought from the early 1830s on, tried to change the meaning of that symbol. They had long seen the credit system as the nerve center of economic development and social change. Amid a welter of publicity, they sought to democratize savings by mobilizing them into an elaborate hierarchy of credit institutions capable of undertaking projects of long duration. The “association of capital” was their theme, and grand, unashamed speculation in future development was their practice. The conflict between the Rothschilds and the Pereires was, in the final analysis, a personalized version of a deep tension within capitalism between the financial superstructure and its monetary base.2 And if, in 1867, those who controlled hard money (like Rothschild) managed to bring down the credit empire of the Pereires, it was, as we shall shortly see, a Pyrrhic victory.

Figure 39 The stock exchange “is other people’s money,” said Dumas and Chargot’s cartoon depicts the Bourse as a haunt of vampires.

The problem in 1851 was to absorb the surpluses of capital and labor power. The Parisian bourgeoisie universally recognized the economic roots of the crisis through which they had just passed but were deeply divided as to what to do about it.3 The government took the Saint-Simonian path and sought by a mix of direct governmental interventions, credit creation, and reform of financial structures to facilitate the conversion of surplus capital and labor into new physical infrastructures as the basis for economic revival. It was a politics of mild inflation and stimulated expansion (a sort of primitive Keynesianism) lubricated by the strong inflow of gold from California and Australia. The hautes banques and their clients were deeply suspicious. Rothschild wrote to the Emperor, vigorously condemning the new initiatives. The government, distrustful of the bankers’ Orléanist political sympathies, turned to administrators like Persigny, the Pereires, and Haussmann, who accepted the idea that universal credit was the way to economic progress and social reconciliation. In so doing, they abandoned what Marx called the “Catholicism” of the monetary base, turned their banking system into “the papacy of production,” and embraced what Marx called the “protestantism of faith and credit.”4 The religious imagery at work here has, however, more than casual significance. The Catholic Church formally equated interest with usury well into the 1840s, and sought to outlaw it. For many devout Catholics, the immorality of the new system of finance was therefore a serious issue. The fact that Rothschild and the Pereires were Jewish, and Haussmann was Protestant, did not help matters in their eyes. Many of them equated capitalism with prostitution, as Gavarni’s cartoon wittily confirms. The moral condemnation of Empire that resurfaced so strongly after its collapse frequently harked back to its financial dealings as irregular and sinful. There were, evidently, moral as well as political, technical, and philosophical barriers to be overcome if a new financial system was to be created.

Figure 40 Many conservative Catholics regarded the charging of interest as akin to prostitution. In this cartoon by Gavarni, a prettily dressed young woman tries to lure a reluctant customer into an investment house (a house of ill repute) by promising him that she will be kind and gentle with him, that she will give him a good percentage return on whatever he cares to lay out!

The story of financial reform under the Second Empire is complicated in its details.5 But the Pereires’ Crédit Mobilier was undoubtedly the controversial centerpiece. Initially formed to get railroad construction and all ancillary industries back in business, it was an investment bank that held shares in companies and helped them assemble the necessary finance for large-scale undertakings. It could also sell debt to the general public at a rate of return guaranteed by the earnings of the companies controlled. It thus acted as an intermediary between innumerable small savers hitherto denied such opportunities for placement (the Pereires made much of the supposed “democratization” of credit) and a wide range of industrial enterprises. They even hoped to turn it into a universal holding company that, through assembly of funds and mergers, would bring all economic activity (including that of the government) under common control. There were many, including those in government, who were suspicious of what amounted to a planned evolution of what we now know as “state monopoly capitalism.” And although Pereires were ultimately to fall, the victim of an aroused conservative opposition and their own overextended speculation (a fate that Rothschild had predicted in his letter to the Emperor and had helped seal), their opponents were forced to adopt the new methods. Rothschild hit back with the same form of organization as early as 1856, and by the end of the Second Empire a host of new financial intermediaries (such as the Crédit Lyonnais, founded in 1863) had emerged and were to dominate French financial life from then until today.

In itself, as the Pereires recognized, the Crédit Mobilier would not be effective without a wide range of other institutions integrated into or subordinated to it. The Bank of France (a private but state-regulated institution) increasingly took on the role of a national central bank. It was much too fiscally conservative for the Pereires’ taste. It took the tasks of preserving the quality of money very seriously, even at the price of tightening credit and raising the discount rate to levels that the Pereires regarded as harmful to economic growth.6 The Bank of France turned out to be the major center of financial opposition to the Pereires’ ideas. It dealt almost exclusively in short-term commercial paper, discounting commercial bills of exchange. The Crédit Foncier, a new institution finally stitched together on December 10, 1852 (shortly after the Crédit Mobilier), was to bring rationality and order to the land and property mortgage market. Founded under the Pereires’ influence, it was to be an important ally in their concerns. Other organizations, such as the Comptoir d’Escompte de Paris (founded in 1848) and the Crédit Industriel et Commercial (1859), dealt in special kinds of credit. And within their own empire, the Pereires, with government blessing, spawned a wide range of hierarchically ordered institutions, such as the Compagnie Immobilière, which concentrated on the finance of property development. At its height the Crédit Mobilier integrated twenty French-based and fourteen foreign-based companies into its extraordinarily powerful organization.

The effects of all this on the transformation of Paris were enormous. Indeed, without some reorganization of finance the transformation simply could not have progressed at the pace it did. It was not just that the city had to borrow (a topic I take up later), but that Haussmann’s projects depended upon the existence of companies that had the financial power to develop, build, own, and manage the spaces he opened up. Thus did the Pereires become “in many respects and in many places the secular arm of the prefect.”7 The Compagnie Immobiliere de Paris emerged in 1858 out of the organization of the Pereires created in 1854 to take on the first of Haussmann’s big projects, the completion of the Rue de Rivoli and the Hotel du Louvre. How the new system worked is well illustrated by what happened in this first case. The decision to raise the capital and build the shopping spaces and the hotel along the Rue de Rivoli was taken as a speculative venture in preparation for the Universal Exposition planned for 1855. The original plan for an arcade of individual shops failed to attract, and so the Pereires accepted a proposal to turn the whole shopping space into one large department store, a new and equally speculative venture. Opened in 1855, the store was badly run and financially unprofitable. The Pereires had to reorganize and recapitalize the whole venture, and it was not until 1861 that it finally made a profit.8 Meanwhile, the Pereires in effect raised capital to lend to the department store to pay off the debt on the capital they had raised for the building venture. If, at any moment before 1861, anyone had questioned the creative accounting involved (or even refused to invest more money) the Pereires would have been in deep financial difficulty. But they finessed the short term and achieved over the long term.

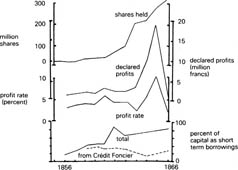

The company went on to build along the Champs Elysées and the Boulevard Malesherbes, and around the Opéra and the Parc Monceau. It increasingly relied, however, on speculative operations as a source of profit. In 1856–1857, it drew three-quarters of its income from rents received on housing and industrial plants, and only a quarter from the buying and selling of land and property. By 1864 the proportions were exactly the reverse.9 The company could easily augment its capital via the Crédit Mobilier (which held half its shares) and bolster its profits by a leveraging operation based on a cosy relationship with the Crédit Foncier (borrowing half of its capital from the latter at 5.75 percent on a project that returned 8.7 percent yielded the company 11.83 percent, Pereire explained to astonished shareholders). The company increasingly shifted to short-term financing, which made it vulnerable to movements in the interest rate dictated by the Bank of France (which explains the Pereires’ impatience with the policies of that institution and their obsession with cheap credit). It also contracted building work out to enterprises financed by the Crédit Mobilier (thereby provoking considerable concentration and increase of employment in the building industry; see table 4), and it sold or rented the buildings to management companies or commercial groups in which the Crédit Mobilier often had a like stake.

The Pereires were masters at creating vertically integrated financial systems that could be put to work to build railroads; to launch all manner of transportation, industrial, and commercial enterprises; and to create massive investments in the built environment. “I want to write my ideas on the landscape itself,” wrote Emile Pereire—and indeed he and his brother did. But they were not alone. Even Rothschild stooped so low as to parlay his property holdings around his Gare du Nord into a profitable real estate venture, and many a builder, contractor, architect, or owner sought profit by the same route. And while this was not, as we shall see, the only system of land development in Paris, it was the primary means for engineering the Haussmannization of Paris.

Figure 41 The operations of the Compagnie Immobilière, 1856–1866 (after Lescure, 1980), distinguishing between total number of shares (rising rapidly after 1866, just before the crash of 1867), the declared profits and profit rates (which plunged after 1865), and the increasing reliance on short-term borrowings after 1860.

But this was only the tip of a veritable iceberg of effects on the economy and life of Paris. Money, finance, and speculation became such a grand obsession with the Parisian bourgeoisie (“business is other people’s money,” cracked Alexandre Dumas the younger) that the bourse became a center of corruption as well as of reckless speculation that gobbled up many a landed fortune. Its nefarious influence over daily life was immortalized afterward in Zola’s La Curée (The Kill) and L’Argent (Money) through the figure of Saccard (loosely based on the Pereires), who in the first of these novels is cast as the grand speculator engaging with the transformation of Paris, and in the second as the financier masterminding investment schemes in the Orient where, he says:

Fields will be cleared, roads and canals built, new cities will spring from the soil, life will return as it returns to a sick body, when we stimulate the system by injecting new blood into exhausted veins. Yes! money will work these miracles.… You must understand that speculation, gambling, is the central mechanism, the heart itself of a vast affair like ours. Yes, it attracts blood, takes it from every source in little streamlets, collects it, sends it back in rivers in all directions, and establishes an enormous circulation of money, which is the very life of great enterprises.… Speculation—why it is the one inducement that we have to live; it is the eternal desire that compels us to live and struggle. Without speculation, my dear friend, there would be no business of any kind.… It is the same as in love. In love as in speculation there is much filth; in love also, people think only of their own gratification; yet without love there would be no life and the world would come to an end.”10

La Curée (The Kill) invokes exactly the same process, but this time within Paris itself. Saccard, having gotten wind of “the vast project for the transformation of Paris,” sets out to profit from the insider knowledge he has (he had even “ventured to consult, in the prefet’s room, that famous plan of Paris on which ‘an august hand’ had traced in red ink the principles of the second network”). Having “read the future in the Hôtel de Ville,” knowing full well “what may be stolen in the buying and selling of houses and ground,” and being “well up in every classical swindle,” he

knew how you sell for a million what has cost you five hundred thousand francs; how you acquire the right of rifling the treasury of the State, which smiles and closes its eyes; how, when throwing a boulevard across a belly of an old quarter, you juggled six-storied houses amidst the unanimous applause of your dupes. And in those still clouded days, when the canker of speculation was but at its incubation, what made a formidable gambler of him was that he saw further than his chiefs themselves into the stone-and-plaster future reserved for Paris.”11

The figure of the great speculator not only takes charge of shaping Paris and its urban form but also aspires to command the whole globe. And the tool is the association of capitals. That Zola should feel so comfortable invoking Saint-Simonian doctrine in its most hubristic form some seventy years after its initial formulation says much about the persistence of this mode of thought in France throughout the century. The formula “money, aiding science, yields progress,” which Zola invoked, resonated at all levels. There could, evidently, be no modernity without assembling the speculative capital to do it. The key was to find a way to bring together the little streamlets of capital into a massive circulation that could undertake projects at the requisite scale. This was precisely what the Pereires were about and what the institutional shifts in finance were meant to accomplish.

It was, however, through the democratization of money at one end that immense centralization of financial power became possible at the other. The top six families held 158 out of 920 seats on company boards registered in Paris in the mid-1860s—the Pereires held forty-four and the Rothschilds thirty-two.12 Complaints about the immense power of a new “feudality of finance” were widespread and exposed critically to the public in popular works such as that of Duchêne.13 This power was felt internationally (the Pereires threatened, said their detractors, to substitute a new international paper money, under their control, for gold) as well as in all realms of urban organization—the Pereires merged the gas companies into a single regulated monopoly, bringing industrial and street lighting to much of Paris; founded (again by merger) the Compagnie des Omnibus de Paris; financed one of the first department stores (the Louvre); and tried to monopolize the dock and entrepôt trade.14

The reorganization of the credit system had far-reaching effects upon Parisian industry and commerce, the labor process, and the mode of consumption. Everyone, after all, depended on credit. The only question was who was to make it available to whom and on what terms. Workers bedeviled by seasonal unemployment lived by it; small masters and shopkeepers needed it to deal with the seasonality of demand—the chain was endless. Indebtedness was a chronic problem in all classes and arenas of activity. But the credit system of the 1840s was as arbitrary and capricious as it was insecure (only land and property gave true security). Proposals for reform of the credit system abounded in 1848. Artisans, small masters, and craft workers sought some kind of mutual credit system under local and democratic control. Proudhon’s experiment with a People’s Bank offering free credit under the banner “Merchants of money, your reign is over!” collapsed with his arrest in 1849.15 But the idea never died. When workers began to organize in the 1860s, it was to questions of mutual credit that they increasingly turned. Their Crédit au Travail, started in 1863, foundered in 1868, hopelessly insolvent with “loans outstanding to forty-eight cooperatives, of which eighteen were bankrupt and only nine could pay.”16 Indifference on the part of government and, more surprisingly, on the part of fellow workers was blamed. Consumer cooperatives ran into similar problems, many families preferring the antagonistic relation and default on debts to local shopkeepers to the economic burden of cooperation in the face of periodic unemployment and lagging real incomes. The municipal pawnshop of Mont-de-Piété continued to be the last resort for the mass of the Parisian populace. The dream of free credit appeared more and more remote. “It entailed,” said a member of the Workers’ Commission of 1867, “the reversal of the entire system of private property on which merchants, landlords, government, etc. lived.”17

The credit system was rationalized, expanded, and democratized through the association of capitals, but at the expense of often uncontrolled speculation and the growing absorption of all savings into a centralized and hierarchically organized system that left those at the bottom even more vulnerable to the arbitrary and capricious whims of those who had some money power. Yet it took a revolution in the credit system to produce the revolution in space relations. Within Paris that process depended, however, upon a much tighter integration of finance capital and landed property. To the manner of this integration we now turn.