Besides the factory operatives, the manufacturing workman and the handicraftsworkers, whom it concentrates in large masses at one spot, and directly commands, capital also sets in motion by means of invisible threads, another army: that of the workers in domestic industries.

—MARX

The collective force and power of workers had proven indispensable to the overthrow of the July Monarchy and their degraded condition subsequently spawned innumerable proposals and movements for social and industrial reform during the 1840s. The question of work therefore lay at the heart of Parisian workers’ concerns in 1848. The exact role in this of skilled workers from the craft tradition—a superior class comprising some 40 percent of the workforce, according to Corbon, writing at the midpoint of Empire—is not, however, an easy matter to determine.1 By the standard account, these workers, confident in their skills but demoralized by chronic insecurity, convinced of the nobility of work as an ideal but constantly distressed by the experience of it, and believing that labor was the source of all wealth, sought a new kind of industrial order that would temper the insecurity of work, alleviate their relative penury, and stave off growing trends toward deskilling and increasing exploitation. Rancière, however, casts doubt upon the power and character of this craft tradition.2 The evidence he adduces, based largely on the writings of worker poets and authors contributing to the newspaper L’Atelier, certainly points to the dangers of romanticizing and homogenizing the craft worker as the bearer of a distinctively proletarian revolutionary consciousness. The workers whose writings and correspondence Rancière studies in detail sought relief from work and had few illusions about the nobility of backbreaking labor. They sought respect from their employers, not revolution. They wanted to be treated as equals and as human beings rather than as hired hands. They wanted immediate solutions and personal help with their individual problems. They showed little interest in the Blanquist idea of a dictatorship of the proletariat, and most looked to the Saint-Simonian movement as a source of financial support and employment rather than as a fecund source of ideas for social reform.

Figure 54 Daumier’s The Worker captures something of both the self-confidence and the subservient position of Parisian workers who the employer Poulot, for one, believed had a far too high opinion of themselves.

But while Rancière’s account administers a corrective to the revolutionary romanticism sometimes pressed by Marxist-inspired labor historians, it is not at all clear that his account captures the sentiments of those workers who did fight on the barricades and participated in the deliberations of the Luxembourg Commission, and who actively supported the efforts of Cabet, Considérant, Proudhon, and the communists/socialists of the time. To be sure, most workers seem to have looked for some form of association, autogestion, or mutualism rather than centralized state control. But the recalcitrance of the bourgeoisie in general, and of employers in particular, often forced them (as it did Cabet, Considérant, Leroux, and others) into positions where they had no choice except to take a more revolutionary stance. While there was, evidently, a good deal of confusion and flux with respect to both agenda and means (particularly resort to violence), there is no question that most craft workers looked to the creation of a social republic in 1848 that would support their efforts to reorganize work and reform the social relations of production so as to set the stage for their own social advancement for decades to come.

The evolution of Parisian industry during the Second Empire took a very special path. Paris at midcentury was by far the most important and diversified manufacturing center in the nation. And in spite of its image as a grand center of conspicuous consumption, it in fact remained a working-class city, heavily dependent upon the growth of production. In 1866, for example, 58 percent of its 1.8 million people depended upon industry, whereas only 13 percent depended upon commerce.3 But there were some very special features of its industrial structure and organization (tables 4, 5, and 6). In 1847, more than half the manufacturing firms had fewer than two employees, only 11 percent employed more than ten, and no more than 425 qualified for the title of “grand enterprises” (more than 500 workers). It was difficult in many cases to distinguish between owners and workers, and Scott shows how the inquiry of 1847–1848 deliberately confused the categories for political reasons.4 Since the craft workers had in any case evolved hierarchical forms of command, there was little basis within the small enterprises for strong class antagonisms (a condition that prevailed throughout the Second Empire and led a whole wing of the workers’ movement, particularly that influenced by Proudhon, to disapprove of strikes, push for association, and confine their opposition to financiers, monopolists, landlords, and the authoritarian state rather than to private property and capital ownership). It was also very difficult to distinguish commerce from manufacturing, since the atelier in the back was often united with the boutique on the street front.

Table 1 Employment Structure of Paris, 1847 and 1860

| 1847 (Old City) | 1860 (New City) | |||||

| Occupation | Firms | Workers | Workers per Firm | Firms | Workers | Workers per Firm |

| Textiles & clothing | 38,305 | 162,710 | 4.2 | 49,875 | 145,260 | 2.9 |

| Furniture | 7,499 | 42,843 | 5.7 | 10,638 | 46,375 | 4.4 |

| Metals & engineering | 7,459 | 55,543 | 7.4 | 9,742 | 68,629 | 7.0 |

| Graphic arts | 2,691 | 19,132 | 7.1 | 3,018 | 21,600 | 7.2 |

| Food | 2,551 | 7,551 | 3.0 | 2,255 | 12,767 | 5.7 |

| Construction | 2,012 | 25,898 | 12.9 | 2,676 | 50,079 | 18.7 |

| Precision instruments | 1,569 | 5,509 | 3.5 | 2,120 | 7,808 | 3.7 |

| Chemicals | 1,534 | 9,988 | 6.5 | 2,712 | 14,335 | 5.3 |

| Transport equipment | 530 | 6,456 | 12.2 | 638 | 7,642 | 12.0 |

Source: Daumas and Payen (1976).

Table 1 Economically Dependent Population of Paris, 1866

| Occupation | Owners | Employees and Workers | Families | Total | % |

| Textiles & clothing | 26,633 | 182,466 | 103,964 | 313,063 | 25.3 |

| Building | 5,673 | 79,827 | 71,747 | 157,247 | 12.7 |

| Arts and graphicsa | 11,897 | 73,519 | 60,449 | 145,865 | 11.8 |

| Metals | 4,994 | 42,659 | 50,053 | 98,906 | 8.0 |

| Wood and furniture | 5,282 | 27,882 | 33,093 | 66,257 | 5.3 |

| Transport | 9,728 | 35,022 | 48,938 | 93,688 | 7.6 |

| Commerce | 51,017 | 78,009 | 101,818 | 240,840 | 18.6 |

| Diverseb | 10,794 | 50,789 | 58,435 | 120,018 | 9.7 |

| Unclassified | 2,073 | 4,608 | 5,417 | 12,098 | 1.0 |

| Total | 128,091 | 575,981 | 533,914 | 1,237,987 | (100.0) |

Source: Rougerie (1971), 10. (N.B. The total population of Paris in 1866 stood at 1,825,274; see table 1.)

a Includes printing, articles de Paris, precision instruments, and work with precious metals.

b Includes leather, ceramics, chemicals.

Table 1 Business Volume of Parisian Industries, 1847–1848 and 1860 (billions of francs)

| Business | 1847–1848 | 1860 |

| Food and beverages | 226.9 | 1,087.9 |

| Clothing | 241.0 | 454.5 |

| Articles de Paris | 128.7 | 334.7 |

| Building | 145.4 | 315.3 |

| Furniture | 137.1 | 200.0 |

| Chemical and ceramic | 74.6 | 193.6 |

| Precious metals | 134.8 | 183.4 |

| Heavy metals | 103.6 | 163.9 |

| Fabrics and thread | 105.8 | 120.0 |

| Leather and skins | 41.8 | 100.9 |

| Printing | 51.2 | 94.2 |

| Coach building | 52.4 | 93.9 |

Source: Gaillard (1977), 376.

These conditions varied somewhat from industry to industry, as well as with location. Apart from food and provisions (in which the distinction between industry and commerce was particularly hard to define), the textile and clothing trades, together with furniture and metalworking, dominated, cut across by all manner of “articles de Paris” for which the city had become, and would remain, justly famous. Most of the classic sectors for capitalist industrial development were, therefore, absent from the capital; and even textiles, which had been important, was by 1847 mostly dispersed to the provinces, leaving the garment industry behind in Paris. Plainly, most of Parisian industry was oriented to serving its own market. Only in the metalworking and engineering sectors could any semblance of a “modern” form of capitalistic industrial structure be discerned.

This vast economic enterprise could not easily be transformed. Yet it underwent significant evolution in terms of industrial mix, technology, organization, and location. It surged out of the depression of 1848–1850 with a surprising elan that first infected light industry and then, after 1853, spread to the building trades and heavy engineering and metalworking, as well as to the garment industry. During the 1860s the pace of growth slowed, particularly in the large-scale industries, and became more selective as to sector and location.

The Enquêtes of 1847–1848, 1860, and 1872, though flawed, permit a reconstruction of the general path of industrial evolution.5 The Enquête of 1860 lists 101,000 firms employing 416,000 workers—an increase of 11 percent over 1847, with most of the net gain due to annexation of the suburbs, since comparable data for old Paris indicate a loss of 19,000 workers. But the number of firms increased by 30 percent, indicating a surprising expansion of small firms. However, the number of firms employing fewer than two workers had risen to 62 percent (from 50 percent in 1847–1848), and the number employing more than ten workers had fallen from 11 to 7 percent. This increasing fragmentation was observable in many sectors and was particularly marked in old Paris. In the clothing trades, for example, the number of enterprises increased by 10 percent, while workers employed declined by 20 percent. The figures for the chemical industry were even more startling—45 percent more firms and 5 percent fewer workers. Machine building, the largest-scale industry in 1847–1848, with an average of 63 employees per firm, had fragmented to an average of 24 workers by 1860.

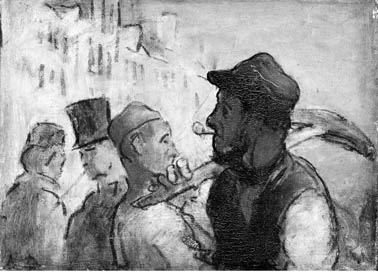

The exact interpretation to be put on this is controversial. On the surface, everything points to the vigorous growth of many very small firms and an increasing fragmentation of industrial structure, a process that continued until the end of the Empire and beyond. Furthermore, this growth and fragmentation of small firms could be seen both close to the center and in peripheral locations. The strong absolute growth of large firms between 1847–1848 and 1860 (the number remained virtually unchanged from 1860 to 1872) was accompanied by their suburbanization. But even here the movement was not uniform. Large-scale printing retained its central location on the Left Bank, while metalworking moved only as far as the inner northern and eastern peripheries. Large-scale chemical operations, however, tended to move much farther out.

Figure 55 Number of large enterprises in different sectors of Paris, according to the surveys of 1836, 1848, 1859, and 1872 (after Daumas and Payen, 1976).

Figure 56 The location of large-scale chemical, metalworking, and printing firms in Paris according to the Enquêtes of 1848, 1859, and 1872 (after Retel, 1977).

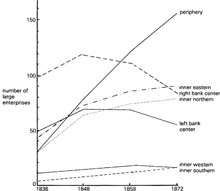

Figure 57 Large factories, like this chemical concern, began to emerge in suburban locations like La Villette in the 1860s.

The case of the chemical industry is interesting to the degree that it captures much of the complex movement at work in Parisian industry during this period. On the one hand, large-scale and often dirty enterprises either were forced out or voluntarily sought out peripheral locations at favored points within the transport network where land was relatively cheap. On the other hand, product innovation meant the proliferation of small firms making specialized products like porcelain, pharmaceuticals, and costume jewelry, artificial flowers, while other industries, mainly in the “articles de Paris” category, generated specialized demands for small quantities of paints, dyes, and the like, which could best be met by small-scale production. Within many industries there was a similar dual movement that saw a growth of some large firms in suburban locations and an increasing fragmentation and specialization of economic activity particularly close to the center.

This highly specialized development had much to do with the maintenance of superior skills of a small group of “superior” workers. The fragmentation and turn to outwork paid by the piece, may also be seen as concessions to the strong predilection of craft workers to conserve their autonomy, independence, and nominal control over their labor process. Yet there was a major transformation of social relations that the raw statistics hide. For what in effect happened, Gaillard convincingly argues, is that there was an increasingly sophisticated detail division of specialized labor in which the products of individuals, small firms, and outworkers and pieceworkers were integrated into a highly efficient production system. Many small firms were nothing more than subcontracting units for larger forms of organization. They therefore functioned more as indentured labor systems beholden to capitalist producers or merchants who controlled them at a distance.6 By having the work done by the piece at home, the capitalists saved on such overhead costs as premises and energy. Furthermore, by keeping these units perpetually in competition for work, the employers could force down labor costs and maximize their own profits. Workers, even though nominally independent, were forced into subservience and into patterns of self-exploitation that could be as savage and as degrading as anything to be found in the factory system.

Within this a much-hated and oppressive system of foremen, overseers, subcontractors (which had been outlawed under the social legislation of 1848 and reinstated after 1852), and other go-betweens could become all too firmly implanted. So though the craft workers continued to be important, their position underwent a notable degradation. The extreme division of labor helped achieve an unparalleled quality and technical perfection in some spheres, but it yielded neither higher wages nor increasing liberty to the worker. It meant, rather, the gradual subsumption of formerly independent craft workers and owners under the formal domination of a tightly controlled commercial and industrial organization. As a consequence, even Poulot (who spent much of his time criticizing the lazy habits and recalcitrance of his workers in the face of authority) ended up admitting,

Paris is the city where people work harder than anywhere else in the world. … When workers come up to Paris from the provinces, they don’t always stay, because so much graft is needed to earn a living. … In Paris, there are certain trades which function by piecework, where after twenty years the worker is crippled and worn out, that is if he is still alive.”7

Behind this general evolution, however, lay a variety of forces that deserve further scrutiny. The reduction of spatial barriers opened up the extensive and valuable Parisian market to provincial and foreign competition (a process further encouraged after the move toward free trade in 1860). But it also meant that Parisian industry had access to geographically more dispersed raw materials and food supplies to feed its laborers and meet its demand for intermediate products at lower cost. Given industry’s powerful base in the Parisian market, this meant that Paris could just as easily compete in the provinces and abroad as it could be competed with.

Paris in fact expanded its share of a growing French export trade from around 11 percent in 1848 to 16 percent by the early 1860s.8 As might be expected, the luxury consumer goods in which Paris specialized were well represented in this vast export surge. But more than half the locomotives and railway equipment and a fifth of the steam engines produced in Paris followed French capital abroad, and even some of the food industry (such as sugar refining) could find a place in provincial markets. The Parisian industrial interest, unlike some of its provincial counterparts, was by no means opposed to free trade, since Parisian manufacturing was evidently capable of dominating provincial and international markets in certain lines of production.

But its advantageous position in relation to this new international division of labor carried some penalties. Parisian industry was more and more exposed to the vagaries of foreign markets. The general expansion of world trade in the period was an enormous boon, of course, but industrialists had to be able to adapt quickly to whims of foreign taste, the sudden imposition of tariff barriers, the rise of foreign manufacturing (that had the ugly habit of copying French designs and producing them more cheaply, though with inferior quality), and the interruptions of war (the American Civil War had particularly dire effects, since America was a major export market). Parisian industry also needed to adapt to the peculiar flow requirements of foreign trade. The growth of the American trade, for example, increased problems of seasonal unemployment. The arrival of raw cotton from America in autumn put money into the hands of American buyers, who spent it as fast as they could in order to get their products back to the United States by spring. Three months of intense activity could be followed by nine months of “dead season.” The Enquête of 1860 showed that more than one-third of Parisian firms had a dead season, with more than two-thirds of those producing “articles de Paris” and more than half in the furniture, clothing, and jewelry trades experiencing a dead season of between four and six months.9 I shall take up the problems this posed for the organization of production and labor markets shortly.

Figure 58 Carpetmaking at Les Gobelins was a typical high-quality artisanal industry that survived during the Second Empire, and benefited from better access to foreign markets (by Doré).

Foreign and provincial competition not only challenged Parisian industry in international and provincial markets, but it also looked with a hungry eye at the enormous and expanding consumer and intermediate goods market that Paris offered. External competition became increasingly fierce in the 1860s. At first, the challenge came from mass-produced goods, in which, with cheaper labor and easier access to raw materials, provincial and foreign producers had a distinct cost advantage that falling freight rates made ever more evident. Shoe production thus dispersed into the provinces, to Pas-de-Calais, l’Oise, and similar places. But where mass production went, luxury goods could all too easily follow. The exact process whereby this occurred can best be illustrated by examining the new relations emerging in Paris between industry and commerce.

The relative power of industrial, financial, and commercial interests shifted markedly in Paris during the Second Empire. While certain large enterprises remained immune, the mass of small-scale industry was increasingly subjected to the external discipline imposed by financiers and merchants. The latter became, in effect, the agents who ensured the transformation of concrete labor to abstract requirements.

The rise of a new credit system favored the creation of large-scale production and service enterprises in several different ways. Direct financing of factory production using modern forms of technology and industrial organization became feasible. In this, the Pereires pioneered the way, but were quickly followed by a whole gamut of financial institutions. But the indirect effects were just as profound. The changing scale of public works and construction (at home and abroad) and the formation of a mass market for many products (signaled by the rise of the department store, itself a child of the credit system) favored large-scale industry. The absorption of small savings within the new credit structures tended also to dry up small, local, and familiar sources of credit to small businesses without putting anything in their place. The net effect was to redistribute credit availability, putting it more and more out of direct reach of small producers and artisans.

The new credit system was not, therefore, welcomed by most industrialists, who saw the financiers—all too correctly, in the case of the Pereires—as instruments of control and merger. The class relation between producers and money capitalists was typically one of distrust. Indeed, the downfall of the Pereires probably had as much to do with the power of commercial and industrial interests within the Bank of France as it did with the muchvaunted personal antagonism of Rothschild. The lengthy polemics waged against the excessive monopoly power of the financiers toward the end of the Second Empire earned the plaudits of artisans and small businesses, and partly explains the growing bourgeois opposition to the economic policies of the Empire.10

Yet the small-scale producers and artisans, faced as they often were with lengthy dead seasons and all manner of settlement dates, had a desperate need for short-term credit. The Bank of France provided discount facilities on commercial paper but served only a very few customers.11 Only toward the end of the period did other financial institutions arise to begin to fill this gap. What existed in their stead was an informal and parallel financing system based either on kinship ties or on small-scale credits offered between buyers and sellers—a system that spread down even into the lower levels of the working class, who could not have survived if they had not been able to buy on time. And it was out of such a system that a newly consolidating merchant class came to exercise an increasing degree of control over the organization and growth of Parisian industry.

Commerce had always had a special place in the Parisian economy, of course. But at mid-century the distinctions between manufacturing and merchanting were so confused that the expression of a distinctive merchant interest lay with various kinds of specialized traders (in wine, for example). Commerce was, for the most part, the servant of industry. The Second Empire, however, was marked by a growing separation of production from merchanting and a gradual reversal of power relations to the point where much of Parisian industry was increasingly forced to dance to the tune that commerce dictated.12 The transformation was gradual rather than traumatic, for the most part. Owners simply preferred to keep the boutique and give up the atelier. But they did not give up a direct relation to the producers. They typically became the hub of a network of subcontracting, production on command or by the piece, and of outwork. In this way an increasingly autonomous merchant class became the agent for the formal subsumption of artisan and craft labor under the rule of merchants’ capital. “Sometimes,” writes Cottereau, “several hundred pseudo-craftworkers and a couple of dozen small workshops were nothing more than the terminal antennae of large clothing interests each with several thousand employees, managed by merchants, industrialists or department stores.” Worse still, these new “nodes of capitalist organization. … were constantly redistributing work, reorganizing their operations, in order to place as many of them as possible in the hands of a workforce without any recognized skills; laborers, women, children and old people.”13

The remarkable degree of fragmentation of tasks and specialization in Parisian industry gave it much of its competitive power and reputation for quality in both local and international markets. And the Second Empire saw increasing refinements in this form of organization. Artificial flower making, which already tended to be specialized as to type of flower in different workshops in 1848, was by the end of the Empire organized into a system of workshops producing parts of particular flowers. Maxime du Camp complained of the “infinite division of labor” that called for the coordination of nine different skills to produce a simple knife.14 That such a system could work at all was entirely due to the efficient organizing skills of the merchant entrepreneurs who supplied the raw materials, organized the detail division of labor among numerous scattered workshops or through piecework at home, supervised quality of product and timing of flows, and absorbed the finally assembled product into well-defined markets.

Figure 59 As early as 1843, Daumier laughed at the organization of the new dry goods stores. The clerk is explaining the intricate route the customer must take to navigate around the store and arrive at his destination in the part of the shop that sells cotton bonnets.

Yet the very same agents who reorganized Parisian industry to ward off foreign competition also brought foreign and provincial competition into the heart of the Parisian market. Under competitive pressure to maximize profits, the Parisian merchants were by no means loath to search out all manner of different supply sources from the provinces and even from abroad, extending their network of commands and outwork well outside of Paris wherever they found costs (particularly of labor) cheaper. They thus stimulated external competition as much as they organized to repel it, and in some cases actively organized the geographical dispersal of some phases of production to the provinces. Foreign and provincial merchants, once an itinerant or seasonal presence in the city, tended to settle permanently and, making use of international and provincial contacts, organized an increasingly competitive flow of goods into the Parisian market. Examples even exist, as in the hat and glove trade, of the separation of production (which went to the provinces) from design and marketing, which remained in the capital.15

There were other developments in merchanting that had a strong impact upon various aspects of Parisian industry. The rise of the large department stores meant the formation of ready-to-wear mass markets. Demand shifted to whatever could be mass-produced profitably, irrespective of its use, value, or qualities. Mass marketing did not necessarily mean mass factory production, but it did imply the organization of small workshop production along different lines (subcontracting being dominant). Worker complaints about the declining concern for quality of product and the deskilling of work in the craft tradition had much to do with the spectacular growth of this kind of trade as large department stores like the Bon Marché (founded in 1852 and with a turnover of 7 million francs by 1869), the Louvre (1855), and Printemps (1865) became centerpieces of Parisian commerce.16

By the 1860s, a hierarchically structured credit system was increasingly becoming the powerful nerve center for industrial development, but it had not yet extended down to the small enterprise. The merchants, well served when necessary by both new and old credit structures, stepped in to become the organizing force for much small industry. The increasing autonomy of this merchant class during the Second Empire was signaled by the formation of distinctive merchant quarters, around the Chaussée d’Antin in the northwest center and, to a lesser degree, around Mail et Sentier and in the northeast center (Rue Paradis, then as now, was the thriving center for glass and porcelain ware). It was from here that local, provincial, and international production for the Parisian market and for export was increasingly organized. These quarters also offered special kinds of white-collar employment opportunities, which left an imprint on the division of social space in the city (see figure 53). Special traditions arose in these quarters with respect to politics, education, religion, and the like that led merchants to participate very little in either the formation or the repression of the Commune.

The increasing autonomy of the merchant class and the rise of new financial power spun a complex web of control around much of Parisian industry, while the merchants’ concern for profit and their geographical range of operation led them toward a restructuring of Parisian industry to meet the conditions of a new international division of labor. The small-scale producers, once proud and independent craft workers and artisans, were increasingly imprisoned within a network of debts and obligations, of specific commands and controlled supplies; were forced into the position of detail laborers within an overall system of production whose evolution appeared to escape their control. It was within such a system that the processes of deskilling and domination, which had been evident before 1848, could continue to work their way through the system of production. That the workers recognized the nature of the problem is all too clear. The Workers’ Commission of 1867 debated the problems at length and put the question of social credit and the liberty of work at the forefront of its social agenda. But by then there had been nearly twenty years in which the association of capital had dominated the noble vision of the association of labor.

Haussmann, as we have seen, had no compunction about expelling noxious or unwanted industry (like tanning and some chemicals) from the city center by direct clearance or use of the laws on insalubrity.17 He also sought by all manner of indirect means (taxation, annexation of the suburbs, orientation of city services) to push most industry, save that of luxury goods and “articles de Paris,” out of the city center. His anti-industry policies derived in part from the desire to create an “imperial capital” fit for the whole of Western civilization, but just as important was his concern to rid Paris of the political power of the working class by getting rid of its opportunities for employment. In this he was only partially successful.18 Though the deindustrialization of the very center was an accomplished fact by 1870, the improvements in communications and in urban infrastructures (gas, water, sewers, etc.) made Paris a very attractive location. Haussmann to some degree counteracted with the one hand what he sought to do with the other. But his failure to attend to the needs of industry and his patent favoring of residential development (for example, in the design of the third network of roads) earned him increasing opposition from industrial interests, which had, in any case, been powerful enough to thwart some of the Emperor’s plans for relocation. And to the degree that provincial and international competition picked up in the 1860s, at the same time that Haussmann’s campaign against industry intensified, the difficulties of Parisian industry were more and more laid at his door, and a lively opposition to Empire was provoked.

Rent was an important cost that Parisian industry had to bear. The rapidly rising rents in the new financial and commercial quarters (Bourse, Chaussée d’Antin) and in the high-quality residential quarters toward the west and northwest either forced existing industry out or acted (on the western periphery, for example) as a barrier to the implantation of new industry. Rising rents in the center either pushed industry out toward the suburbs or forced it to cluster or intensify its use of space in locations of particular advantage. Metalworking, for example, dispersed a relatively short distance toward the northeast, where it found good communications and access to a superior labor supply (see figure 56). The higher-rent areas closer to the center also proved to be very attractive locations (Haussmann compared them to the vineyards on Mount Vesuvius, which improve in fertility with closeness to the top). This was particularly true for those industries for which immediate access to the luxury consumer goods market (or to industries that supplied such markets) was of vital importance. The attractions of a central location were enhanced by the centralization of commerce in the large department stores, the hotels that served a growing tourist trade, and the central market of Les Halles, which drew all manner of people to it.

The public works and urban investments created an additional market of seemingly endless demand (including that for lavish furniture and decoration), much of it concentrated close to the city center. Many industries had a strong incentive to cling to central locations—pharmaceuticals, toiletries, paints, metalworking (particularly of the ornamental sort), carpentry, and woodworking, as well as the manufacturers of modish clothing and articles de Paris. But the high rents had to be paid. And here the adaptation that saw the growth of outwork paid by the piece made a great deal of sense, because the workers then bore either the high cost of rent themselves (working at home in overcrowded quarters) or the cost of inaccessibility to the center. The merchants could save on rental costs while making sure production was organized into a configuration that flowed neatly into the high points of demand. The independent ateliers that did remain were caught in a cost squeeze, which either forced them into the arms of the merchants or pushed them to reorganize their internal division of labor and so reduce labor costs. Rising rents in the city center exacted a serious toll on industry and the laborers, and in so doing played a key role in the industrial restructuring of Paris under the Second Empire.

Figure 60 The tanning factories along the highly polluted Bièvre River are captured in this Marville photo from the mid-1860s. These were the kinds of dirty industries that Haussmann sought to expel from the central areas of the city.

There is a general myth, of which historians are only now beginning to disabuse us, that large-scale industry drives out small-scale industry because of the superior efficiency achieved through economies of scale.19 The persistence of small-scale industry in Paris during the Second Empire appears to refute the myth, for there is no doubt that the small workshops survived precisely because of their superior productivity and efficiency. Yet it is dangerous to push the refutation too far. The industries in which economies of scale could easily be realized (such as textiles and, later on, some aspects of clothing) dispersed to the provinces, and large-scale engineering either suburbanized or went elsewhere. And the small-scale industry that was left behind and that exhibited such vigorous growth achieved economies of scale not through fusion of enterprises but by the organization of interindustrial linkages and the agglomeration of innumerable specialized tasks. It was not size of firm that mattered, but geographical concentration of innumerable producers under the organizing power of merchants and other entrepreneurs. And it was, in effect, the total economies of scale achieved by this kind of industry within the Paris region that formed the basis for its competitive advantage in the new international division of labor.

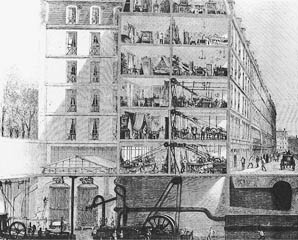

Figure 61 The collective use of steam engines became a feature of Parisian industry during this period. This design, from 1872, illustrates how the system, working through a steam engine in the basement and distributing power to several floors above, allows for the building to be occupied by different businesses.

There is another myth, harder to dispel, that small industry and production by artisans is less innovative when it comes to new products or new labor processes. At the time, Corbon strongly denied this, detecting a very lively interest in new product lines, new techniques, and the applications of science among the “superior” workers and artisans, though he did go on to remark that they tended to admire the application of everything new anywhere but in their own trade.20 But too much success was to be had from product innovation (particularly in the luxury goods sector) for small owners to let the opportunities pass them by. And new technologies rapidly proliferated. Even steam engines, of feeble horsepower to be sure, were organized into patterns of collective use among the ateliers. And the clothing industry adopted the sewing machine, leatherworking used power cutting knives, cabinetmakers used mechanical cutters, and manufacturers of “articles de Paris” were fairly possessed by a rush to innovate when it came to dyeing, coloring, special preparations, costume jewelry, and the like. Building and construction also saw major innovations (such as the use of mechanical elevators).

The picture that emerges is one of lively innovation and rapid adoption of new labor processes. The objections of the craft workers were not to the new techniques but, judging from the Workers’ Commission of 1867 and the writings of workers like Varlin, to the manner in which these techniques were forced on them as part of a process of standardization of product, deskilling, and wage reduction.21 Here, too, the increasing integration of specialized, detailed division of labor under the command of merchants and entrepreneurs gave special qualities to the transformation of the labor process. The evident technological vigor of small industry in Paris was not necessarily the kind of vigor the workers appreciated. And in this they had good reason: as Poulot (an industrialist with a reputation for innovation) admitted, the three key objectives he had in mind in developing innovations were increasing precision, speeding up production, and “to decrease the free will of the workers.”22

In this regard the memoire of Xavier-Edouard Lejeune is instructive.23 Raised in the country by his grandparents, he joined his single mother (the victim, apparently, of a betrayed romance with a bourgeois son of some note) in Paris in 1855, at age ten. He found his mother employing six to eight women in the production of women’s coats of high quality with special connections to certain retailing outlets. That year was the high point of the boom in the clothing trades, as the stimulus given by state expenditures and the rise of fashion at the imperial court and throughout Paris took hold. His mother lived in fairly spacious and central accommodations, employed a maid, and entertained relatives and friends. Six years later she employed only one person and had been forced into a number of moves into smaller quarters at much lower rents. She stopped entertaining and dispensed with the maid; Xavier-Edouard did the housework and the shopping for a while, before being sent out to work, for “reasons of economy,” in a retail store where he received accommodations and food as well as a small wage. The problem for his mother was the advent of the sewing machine and fiercer market competition under conditions of slacker demand. She was gradually driven into poverty (the account fails to mention her after 1868, but later research showed she still practiced a trade in 1872 but was totally impoverished by 1874, when she was declared insane and incarcerated until she died in 1891). For many small owner-workers, the tale was, I suspect, all too common in its broad outlines.

So what was it like, working in Parisian industry during the Second Empire? It is hard to construct any composite picture from such a diversity of laboring experience. Anecdotes abound, and some bear repeating because they probably capture the flavor of the work experience for many.

A recent immigrant from Lorraine in 1865 rents, with his wife and two children, two minuscule rooms in Belleville, toward the periphery of Paris. He leaves every morning at five o’clock, armed with a crust of bread, and walks four miles to the center, where he works fourteen hours a day in a button factory. After the rent is paid, his regular wage leaves him Fr 1 a day (bread costs Fr 0.37 a kilo), so he brings home piecework for his wife, who works long hours at home for almost nothing. “To live, for a laborer, is not to die,” was the saying of the time.24

It was descriptions of this sort that Zola used to such dramatic effect in L’Assommoir (he apparently studied Poulot’s text very carefully in preparation for this novel). Coupeau and Gervaise visit Lorilleux and his wife in the tiny, messy, stiflingly hot workroom attached to their living quarters. The couple are working together, drawing gold wire to make column chain. “There is small link, heavy chain, watch chain and twisted rope chain,” explains Coupeau, but Lorilleux (who calculates he has spun eight thousand meters since he was twelve and hopes someday “to get from Paris to Versailles”) makes only column chain. “The employers supplied the gold in wire form and already in the right alloy, and the workers began by drawing it through the draw plate to get it to the right gauge, taking care to reheat it five or six times during the operation to prevent it from breaking.” This work, though it needs great strength, is done by the wife, since it also requires a steady hand and Lorilleux has terrible spasms of coughing. Still relatively young both of them look close to being broken by the exhausting and demanding regime of work. Lorilleux demonstrates how the wire is twisted, cut, and soldered into tiny links, an operation “performed with unbroken regularity, link succeeding link so rapidly that the chain gradually lengthened before Gervaise’s eyes without her quite seeing how it was done.”

The irony of the production of such specialized components of luxury goods in such dismal and impoverished circumstances was not lost on Zola. And it was only through the tight supervision of the organizers of production that such a system could prevail. Small wonder that the otherwise very moderate workers’ delegation of goldsmiths to the 1867 Exposition complained in their report of “an insatiable capitalism,” which left them defenseless and unable to protest against the “obvious and destructive evil” occurring “in those large centers of manufacture where accumulated capital, enjoying every freedom, becomes a kind of legalized oppression, regulating labor and passing work out so as to create more specialized jobs.”25 This was, interestingly, written in the year of publication of volume 1 of Marx’s Capital in Leipzig.

Gervaise later encounters a very different kind of production process when she visits Goujet, the metalworker, after a frightening journey through the industrial segment of northeast Paris. This was, by all accounts, an incredibly impressive industrial zone. Lejeune in his memoire from the period describes it this way:

There were factories and manufacturing establishments back into the far corners of courtyards and impasses, there were workshops from the ground floor up into the higher floors of the houses and an incredible density of workers giving an animated and noisy atmosphere to the quarter.

Goujet, in Zola’s account, shows Gervaise how he makes hexagonal rivets out of white-hot metal, gently tapping out three hundred twenty-millimeter rivets a day, using a five-pound hammer. But that craft is under challenge, for the boss is installing a new plant:

The steam engine was in one corner, concealed behind a low brick wall. … He raised his voice to shout explanations, then went on to the machines; mechanical shears which devoured bars of iron, taking off a length with each bite and passing them out behind one by one; bolt and rivet machines, lofty and complicated, making a bolt-head in one turn of their powerful screws; trimming machines with cast-iron flywheels and an iron ball that struck the air furiously with each piece the machine trimmed; the thread-cutters worked by women, threading the bolts and nuts, their wheels going clickety-click and shining with oil. …The machine was turning out forty-four-millimetre rivets with the ease of an unruffled giant. … In twelve hours this blasted plant could turn out hundreds of kilogrammes of them. Goujet was not a vindictive man, but at certain moments he would gladly … smash up all this iron work in his resentment because its arms were stronger than his. It upset him, even though he appreciated that flesh could not fight against iron. The day would come, of course, when the machines would kill the manual worker; already their day’s earnings had dropped from twelve francs to nine, and there was talk of still more cuts to come. There was nothing funny about these great plants that turned out rivets and bolts just like sausages. … He turned to Gervaise, who was keeping very close to him, and said with a sad smile, … “maybe sometime it will work for universal happiness.”26

Thus were the abstract forces of capitalism brought to bear on the concrete experience of laboring under the Second Empire.