But it is precisely with the maintenance of that extensive state machine in its numerous ramifications that the material interests of the French bourgeoisie are interwoven in the closest fashion.

—MARX

The French state at midcentury was in search of a modernization of its structures and practices that would accord with contemporary needs. This was as true for Paris as it was for the nation. Louis Napoleon came to power on the wreckage of an attempt to define those needs from the standpoint of workers and a radicalized bourgeoisie. As the only candidate who seemed capable of imposing order on the “reds,” he swept to victory as President of the Republic. As the only person who seemed capable of maintaining that order, he received massive support for constituting the Empire. Yet the Emperor was desperately in need of a stable class alliance that would support him (rather than see him as the best of bad worlds) and in need of a political model that would assure effective control and administration. The model he began with (and was gradually forced to abandon in the 1860s) was of a hierarchically ordered but popularly based authoritarianism. The image he used was of a vast national army headed by a popular leader, in which each person would have his or her place in a project of national development for the benefit of all. Strong discipline imposed by the meritocracy at the top was to be matched by expressions of popular will from the bottom. The task of administration was to command and control.

It is tempting to interpret the gyrations of personnel and policies under the Second Empire as the arbitrary vacillations of an opportunistic dreamer surrounded by venal and grasping advisers. I shall follow Gramsci and Zeldin, who, from opposite ends of the political spectrum, view the Empire as an important transition in French government and politics that, for all its tentativeness, helped bring the institutions of the nation into closer concord with the modern requirements and contradictions of capitalism.1 In what follows, I shall focus on how this political transition took place in Paris and what the consequences were for the historical geography of the city.

Figure 50 Louis Napoleon’s problem, from the very outset, was to maintain a popular basis for his rule. Daumier, in his celebrated depictions of him as an opportunistic figure called Ratapoil, here has him, in 1851 before the coup d’état, attempting to seduce a reluctant France depicted, as usual, in the feminine figure of Liberty. She replies to his advances by saying that his passion is too sudden to be believable.

The idea of “state productive expenditures” derives from the Saint-Simonian doctrine to which the Emperor and some of his key advisers, led by Persigny and including Haussmann, loosely subscribed. Debt-financed expenditures, the argument goes, require no additional taxation and are no added burden on the treasury, provided that the expenditures are “productive” and promote that growth of economic activity, which, at a stable tax rate, expands government revenues sufficiently to cover interest and amortization costs. State-financed public works of the sort that the Emperor asked Haussmann to execute could, in principle at least, help absorb surpluses of capital and labor power, and ensure their perpetual full employment at no extra cost to the taxpayer if they produced economic growth.

The main tax base upon which Haussmann could rely was the octroi—a tax on commodities entering Paris. Haussmann was prepared to subsidize and deficit-finance any amount of development in Paris, provided it increased this tax revenue. He would, for example, virtually give land away to developers but, by tightly regulating building style and materials, ensure an expansion of tax receipts on the building materials entering the city. From this, incidentally, derived Haussmann’s strong partiality for expensive housing for the rich.

The story of Haussmann’s slippery financing has been too well told elsewhere to bear detailed repetition.2 By 1870 his works had cost some 2.5 billion francs, of which half was financed out of budget surpluses, state subsidies, and resale of lands. He borrowed 60 million by direct public subscription (an innovation) in 1855 and sought another 130 million in 1860, which was finally disposed of only in 1862 when the Pereires’ Crédit Mobilier took one-fifth. The loan of 270 million francs authorized after strong debate in 1865 was disposed of only with the active help of the Credit Mobilier. Haussmann needed another 600 million, and the prospects of obtaining another loan were poor. Thus he began to tap the Public Works Fund, which was meant as a floating debt, independent of the city budget, designed to smooth out the receipts and expenditures attached to public works that took a long time to complete. The construction costs were normally paid by the builder, who was then paid by the city in as many as eight annual installments (including interest) after the project was complete. Since the builder had to raise the capital, this was in effect a short-term loan to the city. In 1863, some of the builders ran into financial difficulty and demanded immediate payment on a partially finished project. The city turned to the Crédit Foncier, which, at the Emperor’s urging, lent the money to the builders on security of a letter from the city to the builders, stating the expected completion date of the project and the schedule of payment. Haussmann was, in effect, borrowing money from the Crédit Foncier via the intermediary of the builders. And it could all be hidden in the Public Works Fund, which was not open to public scrutiny. By 1868, Haussmann had raised nearly half a billion francs this way.

Given Haussmann’s association with the Pereires and the Crédit Mobilier, it is hardly surprising that his misdeeds were first revealed in 1865 by Leon Say, an economist of a liberal (i.e., free-market) persuasion and protégé of the Rothschilds. This gave grand ammunition to those opposed to Empire. Jules Ferry’s Comptes Fantastiques d’Haussmann, which exposed the whole process and then some, hit the presses to great effect in 1868. A fiscally conservative, unimaginative, and politically motivated bourgeoisie undoubtedly played a key role in Haussmann’s dismissal. But there was a much deeper problem here, stemming from the form of state involvement in the circulation of capital. Between 1853 and 1870, “the City’s debt had risen from 163 million francs to 2,500 millions, and in 1870 debt charges made up 44.14 percent of the City’s budget.” City finances thus became incredibly vulnerable to all the shocks, tribulations, and uncertainties that attach to the circulation of interest-bearing capital. Far from controlling the future of Paris, let alone being able to stabilize the economy, Haussmann “was himself dominated by the machine he and his imperial master had created.” He was, Sutcliffe concludes, fortunate that national political issues forced him out of power, because an overstretched municipal financial structure “could not have survived the repercussions of the international depression of the 1870s.”3

Figure 51 Construction workers were everywhere after the demolitions truly got going. Here Daumier has two workers speculate that the reason the Tour St. Jacques (to this day an isolated landmark in the city) is being left standing is because it would require an ascent by balloon to demolish it.

Here, as in other times and places (New York in the 1970s springs immediately to mind), a state apparatus that set out to solve the grand problems of overaccumulation, through deficit-financing its own expenditures, in the end fell victim to the slippery contradictions embodied in the circulation of interest-bearing money capital. Indeed, there is a sense in which the fate of Haussmann mimics that of the Pereires. In this respect, at least, the Emperor and his advisers modernized the state into the pervasive contradictions of contemporary capitalist finance. They placed the state at the mercy of financial markets and paid the price (as have many states since).

“I would rather face an hostile army of 200,000,” said the Emperor, “than the threat of insurrection founded on unemployment.”4 To the degree that the 1848 Revolution had been made and unmade in Paris, the question of full employment in the capital was a pressing issue. The quickening pace of public works partially solved the problem. “No longer did bands of insurgents roam the streets but teams of masons, carpenters, and other artisans going to work; if paving stones were pulled up it was not to build barricades but to open the way for water and gas pipes; houses were no longer threatened by arson or fire but by the rich indemnity of expropriation.”5 By the mid-1860s more than a fifth of the working population of Paris was employed in construction. This extraordinary achievement was vulnerable on two counts. First, as Nassau Senior put it, “A week’s interruption of the building trade would terrify the government.” Second, the seemingly endless merry-go-round of productive expenditures put such a heavy burden of debt on future labor that it condemned much of the population to perpetual economic growth and forced work in perpetuity. When the public works lagged, as they did for both political and economic reasons after 1868, falling tax receipts and unemployment in the construction trades became a very serious issue. That this had a radicalizing effect on workers who, contrary to bourgeois opinion, were by no means as opposed to Haussmann, as was generally thought—he was their main source of employment, and they knew it—is suggested by the disproportionate number of construction workers who participated in the Commune.6

The state had some other strings to its bow to stimulate trade. Imperial splendor demanded that the army get new uniforms and that court dress codes be formally established; the fashion of the day become mandatory for status and reputation throughout the city. The stimulus to the clothing trades from 1852 until the late 1850s was immense. Not all labor surpluses could be absorbed by measures of this sort, however. There were vast labor reserves throughout France that flooded into Paris, particularly in the 1850s, partly in response to the employment opportunities created by the public works. So although the indigency rate (an approximate indicator of the labor surplus) dropped from one in every 16.1 inhabitants to one in 18.4 between 1853 and 1862, the absolute number of indigents at no point declined, while the rate itself rose again to one in 16.9 by 1869.7

Haussmann’s policy toward this massive industrial reserve army underwent an interesting evolution. Eighteenth-century traditions of city charity as a right, of the city’s duty to feed the poor (even from the provinces), were gradually abandoned. Haussmann substituted a more modern neo-Malthusian policy. Indeed, given the pressures on the city budget, the size of the welfare problem, and the shifting forms of financing, he probably had no choice. He argued that the city best fulfilled its duty by providing jobs, not welfare, and that if it looked after job creation, it might reasonably diminish its obligation to provide welfare. If the jobs were provided and poverty continued to exist, it was, he hinted, the fault of the poor themselves, who consequently forfeited their right to state support. This is, of course, an argument with which we continue to be very familiar; it was central to the reform of the welfare system in both the United States and Britain in the 1990s. The state apparatus in Paris conceived of its responsibilities toward the poor, the sick, and the aged in a very different way in 1870 than in 1848. This change of administrative attitude toward welfare, medical care, schooling, and the like contributed, Gaillard suggests, to the sense of loss of rights and of community that lay at the root of the social upheavals from 1868 to 1871.7 That such neo-Malthusian policies should have provoked such popular response is not surprising. Certainly, the Commune sought to reestablish these rights, and even Haussmann, seeking to shore up support for an ailing regime, found himself having to pay increasing attention to welfare questions as unemployment increased and the Empire struggled to live up to its own propaganda that it provided welfare as a safety net from the cradle to the grave.

Haussmann adopted similar principles with respect to the price of provisions. When prices rose unduly, social protest usually provoked a hurried state subsidy. But Haussmann believed in a free market, at least for the working and middle classes. If price fluctuations tied to variable harvests caused difficulty, then the answer lay in a revolving fund into which bakers or butchers paid when supply prices were low and from which they withdrew when supply prices were high. The burden on the city budget was negligible, and price stability was achieved. Haussmann thus pioneered commodity price-stabilization schemes of the sort that became common in the 1930s. But he preferred to do without them, and abandoned all such schemes as free-market liberalism came to the center of government policy after 1860. By that time the elimination of spatial barriers and the availability of imports from a variety of sources eliminated the vulnerability of the Paris food supply to national harvest conditions. Coupled with better distribution within the city, this brought greater security to the city’s food supply.

While no simple guiding principles were established in the administration of the city’s immensely complicated social welfare machinery, Haussmann’s instincts led him in two quite modern directions that were, at first sight, somewhat inconsistent with the centralized authoritarianism of Empire. First, he sought to privatize welfare functions wherever he could (as in the case of education, where he conceived of the state’s role as confined to the schooling of indigents only). Second, he sought a controlled decentralization in order to emphasize local responsibility and initiative. The dispersal of the social welfare burden from Paris to the provinces and the decentralization of responsibility for health care, education, and care of the poor into the arrondissements fitted into an administrative schema that, while in no way abandoning hierarchy, connected the expectation of service to local ability to pay. The arrondissements therefore displaced the city as the institutional center to which those in need of welfare services had to go to get their needs met.

The Second Empire was an authoritarian police state, and its penchant for surveillance and control stretched far and wide. Apart from direct police action, informers, spies, and legal harassment, the imperial authorities sought to control the flow of information, mobilized extraordinary propaganda efforts, and used political power and favors to co-opt and control friend and foe alike.8 The system worked well in rural France but was harder to impose on the cities. Paris posed severe problems, in part because of its revolutionary tradition and in part because of its sheer size and labyrinthine qualities. While Haussmann and the prefect of police (often at loggerheads over jurisdictional questions) were the main pinions of surveillance and control, various governmental departments (Interior, Justice, etc.) were also involved. And laws were shaped with this end in mind. Censorship of the press had been reimposed under the Second Republic—“all republican journals were forbidden,” an English visitor noted ironically, “and those only allowed that represented the Orléanist, Legitimist, or Bonapartist factions.”9 The Empire, in its press laws, simply tightened what the republican “party of order” had already imposed. Even the street singers and entertainers, viewed as peddlers of songs and scenes of socialism and subversion by the authorities, had to be licensed, and their songs officially stamped and approved by the prefect, under a law of 1853. The political content of popular culture was hounded off the streets, as were many of the street entertainers themselves. But the frequency with which contemporaries (like Fournel) encountered such characters and the frequency with which Daumier, for one, took them as subjects suggests that the authorities could never squelch this aspect of popular culture entirely.10

Figure 52 The street entertainers were a crucial element in Parisian street life, but controlling them and preventing them from any political pronouncements proved difficult. Daumier is at his very best in this portrait of street musicians in action.

The police (whom the workers always referred to as spies) were far more dedicated to collecting information and filing reports on the least hint of political opposition than they were to controlling criminal activity. While they managed to instill considerable fear, they do not appear to have been very effective at their work, in spite of a major administrative reorganization in 1854. The fear arose from the vast network of potential informers. “The police are organized in the workshops as they are in the cities,” wrote Proudhon; “no more trust among workers, no more communication. The walls have ears.”11 Lodging houses were kept under strict surveillance, their records of those in residence and their comings and goings were regularly inspected, and the concierge often was co-opted into the police network of informers. And when the emperor struck down the workers’ right to association, coalition, and assembly (together with the right to strike) in 1852, he replaced it with a system of conseils de prud’hommes (councils of workers and employers to resolve disputes within a trade) and mutual benefit associations for workers. To prevent both from becoming hotbeds of socialism, the Emperor appointed the administrative officers (usually on the advice of the prefect of police), who furnished regular reports. A similar system of control was established when the right to hold public meetings was finally conceded in 1868—“assessors” with power to monitor and close down unduly “political” meetings were appointed and obliged to file extensive reports. The propaganda system was no less elaborate.12 Controlled flows of news and information through an official and semiofficial press, all manner of official pronouncements, and administrative actions (for many of which the prefect was responsible) sought to convince the popular classes of the merits of those at the top (of the Emperor and Empress, in particular). It was rather as if charitable works and officially sponsored galas, expositions, and fêtes were expected to make up for loss of individual freedom.

Such a system had its limits. It is hard to maintain surveillance and control in an economy where the circulation of capital is given free rein, where competition and technical progress race along side by side, sparking all manner of cultural movements and adaptations. Easier communications throughout Europe turned Brussels into a major center of critical publications, the flow of which into France proved difficult, if not impossible, to stem. The dilemmas of press censorship illustrate the problem. The Parisian press grew from a circulation of 150,000 in 1852 to more than a million in 1870.13 Though dominated entirely by new money interests, the newspapers and journals were diverse enough to create controversies that were bound to touch on government policies. When Say attacked Haussmann’s finances in the name of fiscal prudence, he was eroding the Emperor’s authority. Republican opponents like Jules Ferry could opportunistically follow suit. And censorship could not easily be confined to politics; it dealt with public morality, too. Most of the songs rejected by the authorities were bawdy rather than political,14 and the government got into all kinds of tangles in its prosecutions of Baudelaire, Flaubert, and others for public indecency. The effect was to erode the class alliance that should have been the real foundation of the Emperor’s power. The political system was, in short, ill adapted in this regard to a burgeoning capitalism. Since the Empire was founded on a capitalist path to social progress, the shift toward liberal Empire was, as Zeldin insists, present at its very foundation.15

The same difficulties arose with attempts to control the popular classes. Propaganda as to the Emperor’s merits had to rest on something other than his charity. The formula of “fêtes and bread” did well enough on the fêtes, in which the working classes took genuine delight, but did less well on the bread. Falling real wages in the 1860s made a mockery of claims to social progress and made the fêtes look like ghastly extravaganzas mounted at working-class expense. How, then, could the emperor live up to his own rhetoric that he was not a mere tool of the bourgeoisie? His tactic was to try to co-opt Paris workers by conceding the right to strike (1864) and the rights of public assembly and association (1868). He even promoted collective forms of action. Thus did the French branch of the International Working Men’s Association issue from a government-sponsored visit of workers to the London Exposition of 1862 (provoking the natural suspicion that it was a mere tool of Empire). And though popular culture had been lulled by years of repression into a surface state of somnolence, an underground current of political rhetoric quickly surfaced as soon as the opening came in 1868.16

The urban transformation also had ambivalent effects on the power to watch and control. Many of the dens and rookeries and narrow, easily barricaded streets were swept away and replaced by more easily controlled boulevards. But an uprooted population dispersed from the center, augmented by a flood of immigrants, milled around in new areas like Belleville and Gobelins that became their exclusive preserve. The workers became less of an organized threat, but they became harder to monitor. The tactics and geography of class struggle therefore underwent a radical change.

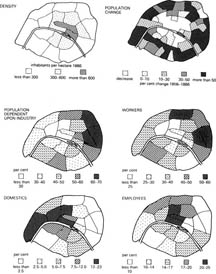

Figure 53 Population density in 1866 and population change in Paris, 1856–1866 (after Girard, 1981; Canfora-Argondona and Guerrand, 1976), and distribution of industrially dependent population, workers, employees, and domestics in Paris by arrondissements in 1872 (after Chevalier, 1950).

“In the space of power, power does not appear as such; it hides under the organization of space.”17 Haussmann clearly understood that his power to shape space was also a power to influence the processes of societal reproduction.

His evident desire to rid Paris of its industrial base and working class, and thus transform it, presumably, into a nonrevolutionary bastion of support for the bourgeois order was far too large a task to complete in a generation (indeed, it was finally realized only in the last years of the twentieth century). Yet he harassed heavy industry, dirty industry, and even light industry to the point where the deindustrialization of much of the city center was an accomplished fact by 1870. And much of the working class was forced out with it, though by no means as far as he wished (figure 53). The city center was given over to monumental representations of imperial power and administration, finance and commerce, and the growing services that spring up around a burgeoning tourist trade. The new boulevards not only provided opportunities for military control, but they also permitted (when lit with gas lighting and properly patrolled) free circulation of the bourgeoisie within the commercial and entertainment quarters. The transition toward an “extroverted” form of urbanism, with all of its social and cultural effects, was assured (it was not so much that consumption increased, which it did, but that its conspicuous qualities became more apparent for all to see). And the growing residential segregation not only protected the bourgeoisie from the real or imagined dangers of the dangerous and criminal classes but also increasingly shaped the city into relatively secure spaces of reproduction of the different social classes. To these ends Haussmann showed a remarkable ability to orchestrate diverse social processes, using regulatory and planning powers and mastering the geography of those neighborhood spillover effects (in which an investment here enhances the value of another investment there), to reshape the geography of the city.

The effects were not always those Haussmann had in mind, in part because the collective processes he sought to orchestrate took matters in a quite different direction (this was true for industrial production, as we shall later see). But his project was also political from the very start and automatically sparked political counterprojects, not simply within the working class but also among different factions of the bourgeoisie. Thus Michel Chevalier (the Emperor’s favorite economist) argued against ridding the city of industry, since this would undermine stable employment and threaten social peace. Until Haussmann had it closed down, Louis Lazare used the influential Revue Municipale not only to execrate the speculations of the Pereires but also to castigate Haussmann’s works for the way they emphasized the social and geographical divisions between “the old Paris, the Paris of Luxury” and “the new Paris, that of Poverty”—a sure provocation, as he saw it, to social revolt. After that, he wrote books denouncing the social effects of Haussmann’s works, but by the time they were published, Haussmann was already gone. Haussmann (and the Emperor) had to seek a coalition of interests in the midst of such warring voices.18

It was the duty of any prefect to cultivate and consolidate political support for the government in power. Since he had no political party behind him and no natural class alliance to which he could appeal, Napoleon III had to find a deeper social basis for his power than a mere family name and support from the army.19 Haussmann needed to help conjure up some such class alliance within a politically hostile city and thus give better grounding to imperial power and, by extension, his own.

The drama of his fall tends to conceal how successful Haussmann was at this, under conditions of shifting class configurations (shaped by rapid urban growth and capital accumulation) and stressful modernization, which were bound to stir “blind discontent, implacable jealousies and political animosities.” Nonetheless, as kingpin in an incredible “growth machine,” he had all kinds of largesse to distribute, around which all manner of interests could congregate. The trouble, of course, is that when the trough runs dry, the interests feed elsewhere. Furthermore, as Marx often noted, the bourgeois is “always inclined to sacrifice the general interest of his class for this or that private motive”—a judgment with which Haussmann concurs, complaining in his Memoires of the “prevalence of privatism over public interest.” In the absence of a powerful political party or any other means for cultivating expressions of support from some dominant class alliance, Haussmann always remained vulnerable to quick betrayal out of narrow material interests.20 His slippery financing, from this standpoint, has to be seen as a desperate move to keep the trough full in order to preserve his power.

Haussmann’s relation with the landlord class was always difficult, since he took a grander view of spatial structure than that defined by narrow private property rights. And the landlord class was itself fragmented into feudal and modern, large and small, central and peripheral. But Gaillard is probably right in sensing “the progressive tightening of the alliance between the Empire and the Parisian property owners.”21 This, however, had as much to do with the transition in the meaning of property ownership as it did with any fundamental adaptation on the part of government. In any case, property owners of any sort are probably the most likely of all to betray class interests for narrow private gain. Haussmann’s alliance with the Pereires was, while it lasted, extremely powerful, but here, too, finance capital was in transition. The downfall of the Pereires and the growing ascendancy of fiscal conservatism in financial circles undermined in the late 1860s what had earlier been a solid pillar of his support. It was, recall, a protégé of Rothschild’s who first attacked Haussmann’s methods of financing. At the same time, Haussmann’s relations with the industrial interests went from bad to worse, so that by the end of Empire they were solidly against him. Here he definitely reaped what he himself had sown in his struggle to rid the city of industry. And commercial interests, though much favored by what Haussmann did, were typically pragmatic, taking what they could but not enthusiastically supportive in return. Most interesting of all is Haussmann’s relation to the workers. These forever earned his wrath and denigration by voting solidly republican as early as 1857.22 And he rarely made attempts to cultivate any populist base. Yet surprisingly little worker agitation was directed at him in the troubled years of 1868–1870, and his dismissal was greeted with dismay and demonstrations in the construction trades. As the grand provider of jobs, he had evidently earned the loyalty of at least part of the working class. And if there were problems with high rents, workers well understood that it was landlords, and not Haussmann, who pocketed the money.

There were deeper sources of discontent that made it peculiarly hard to maintain a stable class alliance within the city. The transformation itself sparked widespread nostalgia and regret (common to aristocrat and worker alike) at the passing of “old Paris,” and contributed to that widespread sense of loss of community which Gaillard makes so much of.23 Old ways and structures were upset. Haussmann knew it, and established institutions to assemble, catalog, and record what was being lost. He established the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris, and Marville was employed to record changes in the urban landscape. But nothing clearly emerged to replace what had been lost. And here the failure to establish an elected form of municipal government for the city surely hurt. For Haussmann steadfastly refused to see Paris as a community in the ordinary sense, but treated it as a capital city within which all manner of diverse, shifting, and “nomadic” interests and individuals came and went so as to preclude the formation of any solid or permanent sense of community. It was therefore vital that Paris be administered for and by the nation, and to this end he promoted and defended the Organic Law of 1855, which put all real powers of administration into the hands of an appointed prefect rather than elected officials. Haussmann may have been right about the transitory qualities of the Parisian community, but the denial of popular sovereignty in the capital was a burning issue that pulled many workers and bourgeois into support of the Commune.24 From this standpoint, Haussmann’s failure to sustain a permanent class alliance had less to do with what he did than with how he did it. But then the authoritarian style of his administration had everything to do with the circumstances that gave rise to the coup d’état in the first place. So it stood to reason that he could not long survive the transition to liberal Empire.

The towering figure of Haussmann dominates the state apparatus of Paris throughout the Second Empire. To say that he merely rode out the storm of social forces unleashed through the rapid accumulation of capital is by no means to diminish his stature, because he rode out the storm with consummate artistry and orchestrated its turbulent power with remarkable skill and vision for some sixteen years. It was, however, a storm he neither created nor tamed, but a deep turbulence in the evolution of French economy, politics, and culture, that in the end threw him as mercilessly to the dogs as he threw medieval Paris to the demolisseurs (demolishers). In the process the city achieved an aura of capitalist modernity, in both its physical and its administrative infrastructures, that has lasted to this day.