Variable capital is therefore only a particular historical form of the labor—fund which the laborer requires for maintenance of himself and his family, and which, whatever the system of social production, he himself must produce and reproduce.

—MARX

The reproduction of labor power, for which women then, as now, bore heavy responsibility, has two aspects. There is first the question of food, sleep, shelter, and relaxation sufficient to return the laborer refreshed enough to be able to work the next day. There are then the longer-term needs, which attach to the next generation of workers through having, rearing, and educating children.

It is probably fair to say that on the average the resources available to the mass of male workers were barely sufficient for daily needs and quite insufficient for long-term needs of child-rearing. This general judgment—which, to be sure, needs much nuancing—is consistent with many of the basic facts of Parisian demography during the Second Empire. In 1866, for example, only a third of the total population could claim Paris as their place of birth. Even in the 1860s, past the peak of the great immigration wave, natural population growth was nine thousand a year, compared to an annual immigration of eighteen thousand.1 The long-term reproduction of labor power appears to have been very much a provincial affair. Paris met its demand for labor, as Marx once put it, “by the constant absorption of primitive and physically uncorrupted elements from the country.” The links with the provinces were more intricate, however, than the bare facts of immigration. Children were often sent back to the provinces to be brought up, and even the working class engaged in that common French practice of putting their children out to rural wet nurses, which, given the high death rate, was more akin to organized infanticide than to the reproduction of labor power.2 Paris was, in any case, full of single males (60 percent of males between twenty-one and thirty-six in 1850). Marriages, if contracted at all, occurred relatively late (29.5 years for men in 1853, rising to nearly 32 years in 1861), and the average number of children per household stood at 2.40, compared to 3.23 in the provinces, with an illegitimacy rate of 28 percent compared to 8 percent elsewhere. Furthermore, the natural population growth there was almost entirely due to the young age structure of the population, itself a function of immigration.

Figure 67 Daumier’s La Soupe depicts family reproductive relations within the working class. Contrasted with the serenity of the bourgeois family (fig. 66), the woman hastily and hungrily consumes a soup while suckling an infant at her breast (hardly in the manner depicted in Daumier’s Republic, fig. 23).

The demographic picture did shift somewhat toward the end of the Second Empire. Household formation picked up in the 1860s and shifted outward to the suburbs, leaving the center single and older in age structure. The chronic slum poverty of the center, which affected mainly new immigrants and the old, was now matched by the suburbanization of family poverty, affecting the young (figure 69). The changing age structure triggered by the vast immigration wave of mainly young unmarried people in the 1850s worked its way through the demographics of the city, quarter by quarter. The idea that those who drew so freely on this labor power had some sort of responsibility or self-interest in its reproduction dawned slowly on the bourgeoisie. And even those, like the Emperor, who saw that bourgeois failure in this regard had had something to do with the events of 1848, were unable to define a basis, let alone a consensus, for intervention. Bourgeois reformers were nevertheless much preoccupied with the question. Fecund with ideas, though short on their application, their inquiries and polemics yielded much information and many ideas that, after the trauma of the Commune, became the basis for social reform under the Third Republic. How and why the configuration of class forces stymied their efforts in housing, nutrition, education, health care, and social welfare deserves careful reconstruction.

The Second Empire witnessed a radical transformation in the system of housing provision. Bourgeois housing was largely captured by the new system of finance, land development, and construction, with the effect of increasing residential segregation within the city. A parallel system of small-time speculative building to meet the demand for working-class housing also sprang up on open land at the periphery. But though the system of housing provision changed, worker incomes remained relatively low, putting fairly strict upper limits on the housing they could afford. A relatively well-off family with stable employment and two people working might make Fr 2,000 a year in 1868 and be able to afford not much more than Fr 350 a year rent. How much and what quality of housing could be provided for Fr 350 or less? Under the best of conditions, the answer was not much; and under the worst, where land and construction were expensive and landlords aggressively sought their 8 percent or more, housing conditions were nothing short of dreadful.

Rapidly rising rents placed an increasing burden on the working population. As early as 1855, Leon Say signaled 20 to 30 percent rises all over the city, so that a single room could not be had for much less than Fr 150. Corbon put rents on working-class housing in 1862 at 70 percent higher than before 1848, and Thomas has housing costs increasing by 50 percent in each decade of the Empire. The statistical series assembled by Flaus indicates a lower figure of between 50 and 62 percent for the whole period, with rents less than Fr 100 increasing by only 19.5 percent. But there were few rents less than Fr 100 to be had; the rent of a single room for registered indigents averaged between Fr 100 and Fr 200 in 1866. A report on the rents paid by these forty thousand or so indigent families put the average at Fr 113 in 1856, rising to Fr 141 in 1866, even after the annexation of the suburbs had brought the cheaper suburban housing into the sample. There is a strong consensus that rising rents outpaced workers’ nominal incomes, particularly during the 1860s.3 The rental increases were consistent with the general rise in property values and affected all social classes. Those living on fixed incomes or even off the stagnant rents of rural estates, and who could afford to pay no more than Fr 700 or so, had a particularly hard time of it. Innumerable cases of hardship and of forced relocation could be found within this segment of the bourgeoisie. But for those who participated in the economic gains of the Second Empire, the rising rents posed no problem. For the more than halfmillion people who lived by their labor in the city, it was an entirely different story.

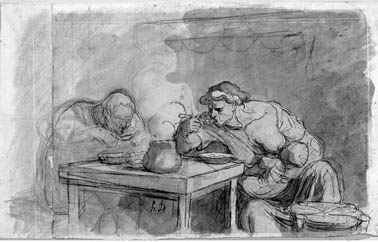

Figure 68 The total population living in lodging rooms in 1876 and the indigence rate in Paris in 1869 (after Gaillard, 1977).

Workers could adapt to this situation in a number of ways. There is evidence, largely anecdotal, that they spent an increasing proportion of their budget on housing. Workers may have been spending as much as one-seventh of their income on housing in 1860, compared to one-tenth in earlier times, and by 1870 the figure may have gone as high as 30 percent.4 They could also save on space. For a family already confined to one room (and that was true for two-thirds of the indigents surveyed in 1866), doubling up came hard, but it was not impossible and far from uncommon for the poorer families. It was easier for single people, and many lodging houses did indeed take on the aspect of barracks, with multiple beds per room for low-paid single workers. It was also possible to seek out lowercost accommodations on the periphery, thus often trading off a long journey to work on foot for a lower rent. But the pressures were such that the rents for speculative housing on the periphery, though lower, were by no means that much lower, particularly given the strong penchant that suburban builders and property owners had for getting their cut of the Parisian property boom by profiteering at the worker’s expense. The last resort was to populate one of the innumerable shantytowns that sprang up, sometimes temporarily, on vacant lots on the periphery or even close to the center.

The paucity of worker incomes relative to rents left its indelible stamp upon the city’s housing situation. And it was partly out of this history that Engels fashioned his famous argument that the bourgeoisie has only one way of solving the housing question: by moving it around. There is no better illustration of that thesis than Paris under Haussmann. The Health Commissioners complained of the temporary shantytowns that arose next door to the new construction sites in the city center. Conditions there, to which everyone turned a blind eye, were simply horrifying.5 The proliferation and overcrowding of lodging houses close to the center; the construction of poorly ventilated, cramped, and poorly serviced dwelling houses that became almost instant slums; and the celebrated “additions,” which in some cases transformed the interior courts behind Haussmann’s splendid facades into highly profitable working-class slums, were all a direct concession that worker incomes were insufficient to afford decent housing. Far from ridding the city of slums, Haussmann’s works, insofar as they assisted the general rise in rents at a time of stagnant worker incomes, accelerated the process of slum formation, even in the heart of the city. On a simple traverse from the city center to the fortifications, Louis Lazare counted no fewer than 269 alleys, courtyards, dwelling houses, and shantytowns constructed without any municipal control whatsoever. Though much of the housing for impoverished families was in the suburban semicircle running around the east of the city, with particular concentrations in the southeast and northeast, there was intense overcrowding of single workers in the lodging houses close to the city center, and there were patches of poor housing even within the interstices of the predominantly bourgeois west.

Such a dismal housing situation could not but have had social effects. It presumably accentuated what was already a strong barrier to family formation, and both Simon and Poulot attributed what they saw as the instability and promiscuity of working-class life to high rents and inadequate housing (thus avoiding, in Poulot’s case, the implication that perhaps the low wages he paid had something to do with it). There was also considerable evidence to connect inadequate and insalubrious housing to the persistent though declining threat of epidemics of cholera and typhoid. Sheer lack of space also forced much social life onto the streets, a tendency exacerbated by the general lack of cooking facilities. This forced eating and drinking into the cafés and cabarets, which consequently became collective centers of political agitation and consciousness formation.

Figure 69 Daumier takes landlords to task for using their power to exclude unwanted elements, such as children and pets, who are then forced to spend their nights on the streets.

With bourgeois reformers deeply aware of and nervous about such a condition and an Emperor who recognized that the consolidation of working-class support through the “extinction of pauperism” (to cite a tract the Emperor had written in 1844) was important to his rule, it is surprising that so little in the way of tangible reform was accomplished. Laws on insalubrity, passed under the Second Republic at the urging of a Catholic reformist, either were used selectively by Haussmann for his own purposes or remained a dead letter—less than 18 percent of the total housing stock was inspected in eighteen years.6 The plan to build a series of cités ouvrières (large-scale working-class housing that drew some inspiration from Fourier’s ideas for collective working-class housing, the phalanstère) was launched in 1849, with Louis Napoleon subscribing some of the funds, but quickly ground to a halt in the face of virulent conservative opposition, which saw cités ouvrières as breeding grounds for socialist consciousness and as potential hearths of revolution. The workers, however, viewed them more as prisons, since the gates were locked at 10 o’clock and life was strictly regimented within. Proposals for individualized housing, more acceptable to the conservative right and the Proudhonists of the left, generated many designs (there was even a competition at the Paris Exposition of 1867) but little action, since the proposal to subsidize the provision of low-income housing had generated only sixty-three units by 1870, and the one cooperative society (to which the Emperor again generously subscribed) had built no more than forty-one units by that same date.

The failure of action in spite of the Emperor’s evident interest (he gave personal financial support to both collectivist and individualized initiatives, inspired articles and government programs, and was responsible for the translation of English tracts on the problem) was partly a matter of confused ideologies. Fourier, with his collectivist model, and Proudhon, who came out very strongly in favor of individual home ownership for workers, split the left. Proudhon’s influence was so strong that no challenge was mounted to property ownership under the Commune, when resentment against landlords was at its height. With such a wide consensus stretching from Le Play on the Catholic right to Proudhon on the socialist left, the only real option was to take care of the housing problem within the framework of private property. But home ownership for the workers was not feasible except with government subsidy. And at that point the government ran up against the powerful class interest of landlords, to whom it was increasingly beholden as a basis for its political power, and a general attachment to freedom of the market, which, for someone like Haussmann, was a cardinal principle of action. Powerful class forces compounded ideological confusion to stymie any action on the housing problem over and beyond the slum clearance that Haussmann masterminded. It was only after the Commune, when the reformers saw that the pitiful slums and inner courtyards were better breeding grounds for revolutionary action than any cités ouvrières could ever have been, that housing reform began to have any teeth.

The “revolution in consumption” facilitated by failing transport costs of agricultural products and by economies of scale and efficiency within the Parisian distribution system did not entirely pass the worker by, even though it also meant an increased “stratification of diet and taste” across the social classes.7 Bread, meat, and wine formed the basis of a distinctive working-class diet (quite different from that in the provinces) and was increasingly supplemented and diversified by fresh vegetables and dairy products. Meat was rarely eaten by itself, of course, but was incorporated in soups and stews, which formed the heart of the main meal. To the degree that diversity and security of food supply improved, there is evidence that standards of nutrition improved at the same time that the cost of living rose. That Paris was still vulnerable to harvest failure became all too evident in 1868–1869, when there was a repeat of the very difficult phase of high prices of 1853–1855. It then became evident, too, that restricted working-class incomes made it difficult for the mass of the population, as opposed to the bourgeoisie, to take advantage of the more diversified food base.

The system of food distribution had some important characteristics. The large lodging-house population and the lack of interior cooking facilities for many families (63 percent of indigents had only a fireplace for food preparation) forced much food consumption and preparation onto the streets and into the restaurants and cafés. The periodicity of worker incomes (during the dead season in particular) meant that much food was purchased on credit. Yet the food typically entered the highly centralized markets (Les Halles) or abattoirs (La Vilette) or wine depots (Bercy) in bulk. The breakdown of bulk via a system of retailers, street vendors, and the like also rested on credit. This opened up innumerable possibilities for small-scale entrepreneurial activity, often organized by women, though here, as in other aspects of life, usually under the ultimate control of men.

This intricate system of intermediation had interesting social consequences. Workers evidently viewed it ambivalently. On the one hand, it provided many opportunities for supplementary employment (particularly of women), and even a chance of upward mobility into the petit-bourgeois world of the shopkeeper. On the other hand, the intermediaries made what were often close to life-and-death decisions as to when and when not to extend credit, and were often viewed as petty exploiters. It was to circumvent this that the workers’ movement began to build a substantial consumer coopertive movement in the 1860s, and many of these cooperatives had considerable success. Nathalie Lemel joined with the indefatigable Varlin to found La Marmite, a food cooperative to which workers could subscribe Fr 50 annually and then have rights to cheap, well-prepared food on a daily basis at much lower cost than in the restaurants. By 1870 there were three branches doing a very busy trade.8 Lemel and Varlin had dual objectives. Not only did they seek to take care of the needs of those who had no place to cook for themselves, but they also saw the cooperatives as centers of political organization and collective action.

In this they were simply confirming the slowly dawning fears of bourgeois reformers: that the mass of the population of Paris, deprived of the facilities and comforts necessary to a stable family life, were being forced onto the streets and into places where they could all too easily fall prey to political agitation and ideologies of collective action. That the cabarets, cafés, and wineshops provided the premises for the elaboration of scathing criticism of the social order and plans for its reorganization was all too evident to Poulot. That they were hearths for the formation and articulation of working-class consciousness and culture became all too apparent as political agitation mounted after 1867. The emphasis that bourgeois republicans like Jules Simon put upon the virtues of stable family life (in a decent house with adequate cooking facilities) was in part a response to the dangers that lurked when food, drink, and politics became part of a collective working-class culture.

The social reformers of the Second Republic had envisaged a system of free, secular, and compulsory state primary education for both sexes. What they got, after the victory of the “party of order,” was the Falloux Law of 1850, which promoted a dual system of education—one religious and the other provided by the state—while bringing all teaching under the supervision of local boards in which the traditional power of the university was now matched by that of the church and of elected and appointed officials. It is generally conceded that the law brought few benefits and many liabilities. Coupled with niggardly state educational budgets, it contributed to the dismal record of educational achievement during the Second Empire.9

Problems arose in part because educational policy lay at the mercy of church-state relations. Anxious to rally Catholics to his cause, the Emperor not only supported the Falloux Law but was reluctant to undermine its spirit until 1863, when, already at loggerheads with the Pope over his Italian policy, he appointed Duruy, a liberal freethinker and reformer, as Minister of Education. Duruy struggled against great odds and with only limited success to give a greater dynamism to the state sector and thus undermine the power of the church. His moves toward free and compulsory primary education and toward state education for girls were often vitiated by legislative tampering and meager educational budgets. But there were all kinds of other conflicts. Apart from the interminable philosophical and theological debates (religion versus materialism, for example), there was no clear consensus within the bourgeoisie as to the objectives of education. Some saw it as a means of social control that should therefore inculcate respect for authority, the family, and traditional religious values—a total antidote to socialist ideology, which some teachers had been rash enough to promote in the heady days of 1848. Even traditionally anticlerical republicans were content to see a hefty dose of religion in education if it could protect bourgeois values (hence the support many of them gave to the Falloux Law). The trouble was that the religious values promoted within the church were, for the most part, of an extraordinarily conservative and backward variety. As late as the 1830s the church had preached against interest and credit, and by the 1850s it was little enamored of materialist science. The church’s backwardness in such matters in part accounts for the violent anticlericalism of many of the students (particularly medical students) who made up the core of the Blanquist revolutionary movement.10

Others, however, saw education as a way to bring the mass of the population into the spirit of modern times by inculcating ideals of free scientific inquiry and of materialist science and rationality appropriate to a world of scientific progress and universal suffrage. The problem was how to do it. Some, like Proudhon, were deeply antagonistic to state-controlled education (it should always remain under the control of the father, said Proudhon), while others feared that without centralized state control there would be nothing to stop the spread of subversive propaganda. Duruy struggled for responsible and progressive education, and was simultaneously appreciated and vilified on all sides. Given such confusions, it is not surprising that the net outcome was meager progress for educational provision and equally meager progress in educational content. Yet the debate in the 1860s over the role of education was to have a lasting influence on French political life.11 Progressive Catholics and republicans alike were, in education as in housing and other facets of social welfare, striving to define a philosophy and practice that would give mass education a new meaning in bourgeois society. The debate was vital, even if the achievements before 1870 were minimal.

To the degree that Paris drew its labor power from the four corners of France, the general failure to improve education had a serious impact upon the quality of labor power to be had there. The general decline in illiteracy throughout France was helpful, of course, but it still left around 20 percent of Parisians illiterate by 1872; and even many of those who could read and write had only the most rudimentary form of education, leaving them with marginal abilities when it came to any kind of skill demanding formal schooling. There was little in the educational system of Paris to offset this dismal national picture. The government initially sided with those who saw education simply as a means of control. State and religious schools developed equally side by side.12 Haussmann’s budget allocations to education were parsimonious in the extreme when compared with his lavish expenditures on public works. He looked to religious and private schools to meet the needs of new immigrants and the newly forming suburban communities, and did his best to limit free schooling to the children of indigents, so payment to attend state schools was commonly demanded. Teachers’ pay, around Fr 1,500 a year, was barely sufficient to make ends meet for a single person, and certainly insufficient to raise a family. For purely budgetary reasons Haussmann (and quite a few taxpayers) preferred to leave schooling to the private sector, particularly to the religious institutions, where teachers’ pay was even lower (around Fr 800).

This picture began to change only after 1868, when Duruy finally forced through the principle of free public education and Greard set about reforming educational provision in Paris. But by then Haussmann’s laissez-faire and privatist strategy had shaped a very distinctive map of educational provision in the city. The annexed suburbs formed what can only be described as an educational wasteland of few and inadequate public schools and weak religious or private development, since this was hardly an area of affluent parents who could afford to pay. Haussmann’s neglect of schooling here is best evidenced by the fact that he spent only four million francs on new schools in the annexed zone between 1860 and 1864, compared to forty-eight million for the new mairies, sixty-nine million for new roads, and five and one-half million for new churches. The rate of school attendance was low and illiteracy higher than the city average. Here were to be found those “ragged schools” in which were assembled “children of all ages who had nothing in common save their … degree of ignorance.” Here was the space of social reproduction of an impoverished and educationally marginalized working class. In the bourgeois quarters of the west, Haussmann’s system worked, since the public schools were used free by the poor quite separately from the private and religious schooling preferred by the bourgeoisie. In some of the central quarters populated by craft workers, petit bourgeois, and those in commerce, the public schools were seen as a common vehicle for educating all children in technical and practical skills, which the Catholic schools found it difficult to impart. Thus the increasing social segregation of space in the city was reflected in the map of educational provision.13

The qualities of this educational system also varied greatly. While there were progressive Catholic schools (and the church put special emphasis upon its efforts in education in Paris), the state sector usually had an advantage in science and other modern subjects. However, the tight surveillance of teachers made possible by the supervisory boards set up in 1850 kept the whole of the educational system biased toward control and religious indoctrination rather than enlightened materialism. But to the degree that the Catholic schools preached intolerance as well as respect for traditional values they became less and less popular with the liberal bourgeoisie, many of whom turned to the Protestant schools. The education of girls was left, until Duruy’s reforms of the late 1860s, almost exclusively in the hands of the church. Interestingly enough, it was here that the question of the proper balance between moral teachings and vocational skills became most explicit as the issue of women’s role came to the fore.

The failures of the formal educational system to produce a labor force equipped with modern technical skills would not have been so serious were it not for a breakdown of other, more traditional modes of skill formation. The apprenticeship system, already in serious trouble by 1848, went into a generalized crisis in the Second Empire.14 In some trades, given the pressures of competition and fragmentation of tasks, apprenticeship degenerated into cheap child labor and nothing else. The geographical dispersal of the labor market and the increasing separation of workplace and residence created a further strain within a system that had always been open to abuse unless there was close surveillance and control by all parties involved. The system seems to have survived reasonably well in only a few trades, such as jewelry. Furthermore, even some of the traditional provincial centers of skill formation for the Parisian labor market were more and more cut off as seasonal migrations gave way to permanent settlement. There therefore arose, on the part of both employers and the working class, a demand for a school system that could replace the apprenticeship system through vocational training and skill formation in educational institutions. The few private institutions that were formed in the 1860s realized some success, thus pioneering the way for educational reform after the Commune. But it was mainly the children of the petite bourgeoisie or well-off workers who could afford the time or money to attend them. The same limitation affected the popular adult education courses that were established in central city areas in the 1860s.

The rudiments of working-class education then, as now, were imparted in the home, where, according to most bourgeois observers and in spite of Proudhon’s injunctions, the woman usually played the main role. Simon’s strong interest in the education of women in part derived from what he saw as the need to improve the quality (moral as well as technical) of the education that mothers could impart. Thereafter, children’s education ran up against the conflict “the more they earn, the less they learn”—a vital problem for households close to the margin of existence. Much of the uneducated working class proved hostile to compulsory education and the apprenticeship system for this very simple reason. A different attitude prevailed among craft workers, who venerated the apprenticeship system and bewailed its degeneration. It was from this sector of the working class that the demand for free, compulsory, and vocationally oriented education was most strongly voiced. And they were prepared to take matters into their own hands. There was no lack in Paris of dissident free-thinkers and students anxious, as the Blanquists were, to offer education for political reasons or, more frequently, for small sums of cash. Varlin, for example, both educated himself and learned principles of moral and political economy from a part—time teacher.15 Herein, as the more savvy members of the bourgeoisie like Poulot realized, lay a serious threat: the autodidacts among the craft workers, with their freethinking and critical spirit (their “sublimism”), might lead the mass of uneducated laborers in political revolt. That the freethinking students who formed the core of the Blanquist revolutionary movement, who joined the International, or who adhered to the popular radical press could take on similar radicalizing roles also became all too apparent in the numerous public meetings to which many an uneducated worker was drawn after 1868. And it was, after all, in the educational wasteland of the periphery that the anarchist Louise Michel began her extraordinary and turbulent career as a teacher. From this standpoint, the bourgeoisie was to reap the harvest of its own failure in the field of educational reform and investment—a lesson it was to take to heart after the Commune, as education became the cornerstone of its effort to stabilize the Third Republic.

What really went on in the heart of the family, whether legally constituted or not, is for the most part shrouded in mystery. How effective the kinship system was in integrating immigrants into Parisian life and culture and in providing some kind of social security is likewise open to debate. The occasional biographies and autobiographies (such as those of Nadaud, Varlin, Louise Michel, and Edouard Moreau) indicate the tremendous importance of family (or free union) and kin within the social networks of Parisian life. Yet we are dealing here not only with politically active people, but also with educated craft workers or petit bourgeois professionals or shopkeepers whose social condition, as we have seen, was quite different from that of the mass of uneducated immigrants. Many of the latter, however, drew their mates from their province of origin and presumably imported into Paris as many systems of family and kin relations as existed in provincial France.16 For the first generation of such immigrants, the Parisian melting pot probably had little meaning, and through the formation of distinctive colonies from Brittany, Creuse, Auvergne, and Alsace, they could even preserve provincial cultures within the overall frame of Parisian life. Yet there are many indications also of a too rapid melting into the alienation and anomie of large-scale urban culture. The unclaimed bodies from the hospitals, the high rates of children apprehended for vagabondage, the orphans and abandoned children, all point to the breakdown of traditional security systems embedded in the family and kinship organization in the face of insecurity of employment, wretched living conditions, and all the other pathologies and temptations (drink, prostitution) of Parisian life.

Figure 70 Most of the time Daumier depicts family life as anything but idyllic, as in this disastrous episode. This is in marked contrast to the idealized serenity that often characterizes the women impressionist painters of the period, such as Cassatt and Morisot.

Within the family and kinship systems that did survive, it appears that the older woman acquired a certain prestige, based upon her capacities as mother, nurse, and educator, as the manager of the reproduction of labor power within the home. This was a role that many men clearly valued, that bourgeois reformers sought to encourage as a pillar of social stability, and that the church sought to colonize through the education of girls as purveyors of religious values and morality. Such a role was doubly important because one of the key values that women were expected to inculcate was respect for the authority of the father within the home and of church or state outside the home. That such an ideology was hegemonic is suggested by the fact that the farthest most radical feminists went was to claim mutual respect within free union. For it was, as we saw earlier, almost impossible for a woman to survive, economically or socially, outside of a liaison with a man.

Even though women may have controlled the purse strings, there was all too often too little in the purse to provide for the proper reproduction of labor power. The dead season meant terrible seasonal strains on income, and rent payment dates (customarily three or six months in advance) put a similar strain on expenditures. It was hard for families to stay together under such material conditions without some other forms of support. The numbers with savings in the caisses d’epargne (set up in 1818 and consolidated in 1837 to promote working-class thrift) expanded enormously, but the average amount put by fell to around Fr 250 per depositor by 1870—enough for a rainy day or two but not much more. The other resource—to farm out children to kin—probably was equally limited insofar as most kin were in the same financial boat.17 Where the kinship system was probably most effective, however, was in tracking down employment opportunities for those in immediate need. Outside of this, the family had to look to state or charitable support.

Paris had traditionally been the welfare capital of France, with a tradition of religious and state charity as a right that all indigents could claim. This system, under attack by conservative republicans in the Second Republic, was steadily dismantled by Haussmann, whose neo-Malthusian attitudes to the welfare question we have already noted. The idea, of course, was to reduce the fiscal burden and to force welfare provision back within the framework of family responsibilities—a strategy (then, as now) that would have made more sense if families had had the financial resources to meet the burden. As it was, hospitals and medical care could not be so easily displaced, and the poverty problem was such as to keep support for indigents a major item in the city budget.

Haussmann’s strategy of decentralization and localization of responsibility for welfare provision simply kept pace, in the end, with the rapid suburbanization of family and child poverty. The only other strategy was to look to the formation of mutual benefit societies and other forms of mutual aid within the working class. The government took several steps to encourage such organizations but was terrified that they might become centers of secret political mobilization—which, of course, they did. Their considerable growth and their attempted surveillance and control by the government forms an interesting chapter in the struggle for political rights and economic security. Women found it hard to gain access to such societies, and they could not independently draw upon their benefits—a limitation that in part undermined the fundamental aim of support to the family. But the government’s insistence on strict surveillance and control also limited the development of the societies in important ways. Here, as with the surveillance system that attached to welfare for indigents, the authoritarian state was stepping crudely down a road toward the policing of the family, which was to be trodden with much greater sophistication by subsequent generations of bourgeois reformers.