‘what it’s like’ Introduced into the consciousness literature by Brian Farrell (1950) in his paper ‘Experience’, the phrase ‘what it’s like’ is typically used to elucidate the notion of phenomenal consciousness: *phenomenal states—and only phenomenal states—are said to possess or bring with them a ‘what it’s likeness’. There is something distinctive that it is like to have a headache, to taste burnt butter, and to listen to the opening bars of Keith Jarrett’s Köln concert. Phenomenal states have phenomenality in common—there is something it is like to be in each of them—and they are distinguished from each other by their phenomenal characters—what exactly it is like to be in each of them. In one sense of that multiply used term, ‘what it’s likenesses’ can be identified with *qualia. We can also use the notion of ‘what it’s likeness’ to explicate one (note: not the only) notion of creature consciousness, for we can say that a creature is conscious when, and only when, there is something it is like to be it. By definition, there is nothing that it is like to be a *zombie.

Although the notion of ‘what it’s likeness’ plays a central role in some of the most fundamental problems associated with consciousness, it is far from clear that there is a uniform conception of ‘what it’s likeness’ at work in the literature on consciousness (Byrne 2004). Certainly theorists give wildly different accounts of the kinds of mental states that possess a distinctive ‘what it’s likeness’. Suppose that you are looking at a yellow vehicle weaving in and out of traffic. You recognize it as a Volvo GL240. What is it like for you to have this kind of visual experience? All hands are agreed in holding that there is something distinctive that it is like to see the car as yellow, as shaped a certain way, and as moving; but consensus ends around about here. Some theorists hold that as far as visual experience is concerned, ‘what it’s likeness’ attaches only to low-level properties such as these. Other theorists hold that ‘what it’s likeness’ attaches to a much-wider range of properties—that there might be something distinctive that it is like to see the car as a car, as a Volvo, or, indeed, as a Volvo GL240. We might call theorists of the former persuasion ‘phenomenal conservatives’ and those of the latter persuasion ‘phenomenal liberals’. A typical conservative might allow that there is a ‘what it’s likeness’ associated with bodily sensations (aches, pains, orgasms), low-level perceptual states (seeing yellow, tasting sourness, hearing something as approaching), and various affective states (anger, fear, elation), but that’s about it as far as ‘what it’s likeness’ extends. A phenomenal liberal, by contrast, might hold that the range of ‘what it’s likeness’ includes not only high-level perception (such as seeing an object as a specific type of car) but also includes such cognitive states as judging that it would be a good idea to go to the south of France in April, wondering whether whales are mammals, and hoping that New Zealand will win the cricket. The debate between conservatives and liberals is a puzzling one: whether or not (say) high-level perception possesses a distinctive ‘what it’s likeness’, should this fact not be apparent (indeed: readily apparent!) to all parties to the debate? The fact that it is not suggests that conservatives and liberals may not have a shared understanding of the phrase ‘what it’s likeness’.

Much of the debate surrounding ‘what it’s likeness’ concerns epistemic status. Whereas one can know what it is to be in a particular physical state without being in the state in question, a number of theorists have argued that one cannot know what it is to be in a particular phenomenal state without having been in it (or one of its near relatives). Indeed, the ‘what it’s like’ locution is most closely associated with a paper whose central purpose is to make such claims vivid. In his paper ‘What it is like to be a bat?’ Thomas Nagel (1974) argues that we face profound challenges in grasping alien experiential perspectives, such as those possessed by the bat. The epistemic challenges posed by ‘what it’s likeness’ are also to the fore in Frank Jackson’s *knowledge argument. Jackson claims, with some plausibility, that Mary learns something new when she first sees red—something that she could not have learnt without seeing red. Again, many take an upshot of Jackson’s argument to be that one cannot know what it is like to instantiate a certain phenomenal property without having instantiated that property (or, at least, a very similar property). When it comes to knowing what it’s like—so the claim goes—there is no substitute for experience.

A related sort of epistemic challenge posed by the ‘what it’s likeness’ of consciousness concerns our inability to grasp how it might be explained. This is Joseph Levine’s famous *explanatory gap. There seem to be principled difficulties in explaining both why there should be anything it is like to be in certain mental states, and why particular conscious states have the ‘what it’s likeness’ that they do. Although the explanatory gap is often put in terms of a gap between phenomenal properties and physical (or functional) properties, it is actually much broader than that. The problem, in a nutshell, is that we do not have a good grip on how to explain facts about ‘what it’s likeness’ in any terms.

But perhaps there are no such facts—at least, perhaps there are no such facts over and above facts about discriminatory responses. Dennett invites us to consider two coffee tasters, Mr Chase and Mr Sanborn (Dennett 1988). Chase and Sanborn no longer like a certain coffee that they both once liked, but they give different accounts of why they no longer like it. Chase says that the flavour of the coffee has not changed, it is just that he no longer likes that flavour; Sanborn says that he still likes that flavour, the problem is just that the coffee does not taste the way that it used to. Dennett suggests that although Chase and Sanborn describe their predicaments in different ways, there may in fact be only a verbal difference here, and that what it’s like for a subject to enjoy a certain phenomenal state cannot be prised apart from the various discriminatory responses that the state facilitates. Dennett’s deflationism is attractive, for it promises to dissolve some of the thorniest problems posed by consciousness. But is it right? Is it true that all that needs to be explained when one listens to the opening bars of Keith Jarrett’s Köln concert is a cluster of discriminatory responses? Believe it if you can.

TIM BAYNE

Byrne, A. (2004). ‘What phenomenal consciousness is like’. In R. Gennaro (ed.) Higher-Order Theories of Consciousness.

Dennett, D. (1988). ‘Quining qualia’. In Marcel, A. and Bisiach, E. (eds) Consciousness in Contemporary Science.

Farrell, B. (1950). ‘Experience’. Mind, 49.

Nagel, T. (1974). ‘What is it like to be a bat?’. Philosophical Review, LXXXIII.

wine and consciousness Of all the consciousness-modifying substances developed by human civilizations, wine is the most ancient (traceable at least back to 5000 BC) and the most widespread (produced in at least 65 of the world’s countries). It is also the substance most rich in meaning and significance in western European civilizations, widely used for ritual and celebratory purposes.

Wine (in this sense) is the product of the fermentation of crushed grapes, their natural sugars turned to alcohols by the activity of naturally occurring, or added, yeasts. Ethanol is the characteristic alcohol in wine, but various acids, esters, acetates, and lactates are also contained in the final product (see Goode 2005).

Alcohol is classified as a depressant in the sense that it suppresses the reactions of the central nervous system. A significant effect of wine upon consciousness is, of course, intoxication by alcohol. Since the earliest stories of wine drinking—e.g. the story of Noah in the biblical book of Genesis—wine’s capacity to intoxicate has been a source of its value and also of its power over people.

But wine is also valued for its effects that fall short of intoxication. Wine is thought to encourage conviviality, conversation, and romance. Plato recommended that middle-aged men drink wine ‘to renew their youth, and that, through forgetfulness of care, the temper of their souls may lose its hardness and become softer and more ductile’. And Immanuel Kant believed that when drinking wine ‘we forget and overlook the weaknesses of others’ (see Crane 2005 for details).

Wine differs from other consciousness-modifying substances in at least two ways. The first is in its meaning or significance. Intoxication through wine-drinking was an important part of ancient Greek religions, such as the Dionysian cults, and it still has a ritual and religious function in many contemporary Western societies, notably in Jewish and Christian rituals. In the Jewish tradition, wine is drunk during the Kiddush, a blessing said before eating on the Sabbath; and at the Passover meal the drinking of wine is obligatory. The main place of wine in Christian ritual is in the sacrament of the Eucharist. Roman Catholics and many other Christians believe that in this ritual wine is transformed into (or in some other way comes to symbolize) the blood of Christ.

The second difference lies in the amount of attention that has been given by writers to the effects of wine on consciousness. Many poets (Keats, Shakespeare, out of many other examples) have discussed the intoxicating effects of wine and its effects on other human appetites. But there is also a long tradition of writing about the extraordinary variety of tastes contained in the world’s different wines. Much of what is written aims to describe precisely the sensory qualities of the experience of drinking wine. Wine writing therefore serves as an excellent source of *phenomenological descriptions of experience, ranging from the simple (‘sour’, ‘sweet’, ‘fruity’, etc.) through the imaginative and comparative (‘velvet’, ‘tar’, ‘tobacco’) to the extravagant and simply incomprehensible (‘wet slate’).

TIM CRANE

Crane, T. (2005). ‘Excess’. The World of Fine Wine, 4.

Goode, J. (2005). Wine Science.

Johnston, H. (2004). The Story of Wine, 2nd edn.

Smith, B. C. (ed.) (2007). A Question of Taste.

working memory Working memory refers to online processing and temporary storage of information in the service of ongoing tasks. It is the system that supports moment-to-moment monitoring and updating, helping us keep track of what we have just done, what we are doing now, and what we plan to do in the very near future. While it would seem to have much to do with conscious experience, direct tests of this link have been relatively rare, and have tended to focus on conscious experience of mental visual images.

Working memory also refers to a group of theories that have been developed largely from empirical findings to account for the functioning of what might be viewed as a mental workspace. Broadly, these theories ascribe similar characteristics to the concept of working memory, namely that it is limited both in the amount of information that can be held at any one time, and in the time for which specific information can be held. This limited capacity supports temporary storage of details of recently viewed objects or scenes as well as sequences of numbers, letters, or words recently read or heard, and current goals and intentions. It also supports manipulation of the information that it stores, hence the concept is of something more than just a passive memory system. However, the theories differ as to precisely how working memory is organized and how its functions are provided, and few directly refer to consciousness.

Finally, working memory refers to a neurobiological network in the brain, but the mapping between the neurobiology and the conceptual theories is the subject of debate. Some researchers argue that working memory comprises simply the currently activated aspects of long-term memory. Others argue that working memory relies on a different (but overlapping) neuroanatomical network from long-term memory, and that selective brain damage can damage working memory function but leave long-term memory intact and vice versa. This entry cannot be comprehensive but will focus on empirical approaches to the link between working memory and consciousness. Detailed reviews of the different theories of working memory are given in Miyake and Shah (1999), and more recent research on the topic is described in Osaka et al. (2007).

There have been four broad approaches to the topic. One of these has examined the cognitive processes and particularly working memory functions that appear to correlate, or do not correlate, with conscious experience such as mental *imagery. A second involves experimental manipulations that appear to disrupt the vividness of conscious experience in healthy individuals. A third draws on studies and observations of individuals who report having no experience of mental visual images or have lost this experience following *brain damage. The fourth offers a more theoretical and philosophical treatment. In all cases, while there is the generally agreed broad definition of working memory given above, it is not clear that there is an equivalent generally agreed definition of *consciousness. For the purpose of this entry, a conscious experience is assumed if the participant reliably and consistently reports such an experience. The focus will be primarily, but not exclusively, on visual mental images because this is the topic that has received the most attention in the experimental psychology literature on working memory and conscious experience. Further, there will be two recurring questions throughout the article: (1) Does conscious experience necessarily reflect the function of working memory? (2) Are working memory functions necessarily available to conscious inspection?

1. Self-report of mental imagery and working memory

2. Experimental manipulation of vividness

3. Working memory, conscious experience, and brain damage

4. Theoretical and philosophical issues

5. Summary and conclusion

One way to study conscious mental experience experimentally is to investigate what factors might affect the vividness of that mental experience. Self-report of the vividness of the conscious experience of mental images can be traced back to the work of Francis Galton in the late 19th century, who asked his colleagues and friends to imagine and then to report the vividness and clarity of their mental recollection of the details of their breakfast table, of light and colour in a cloudy sky, of familiar sounds, smells, taste, touch, hunger, cold, and so on. He observed that people varied dramatically in whether or not they reported having any phenomenal experience of this kind in the absence of the object, scene, or other relevant stimulus.

One of the most common self report measures in use today is the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ) originally developed by Marks (1973). It is similar to the original Galton questionnaire in that it asks individuals to give a rating of how vivid are their conscious mental experiences when recollecting a sunrise, a close relative or friend, and a familiar shop or landscape. The advantage to the latter questionnaire is that it has been used very widely. As a result, it is known to generate a spread of scores in the normal population, to be reliable on test–retest with the same individuals, and to correlate with other measures of visual imagery experience. It also appears to be sensitive to loss of visual imagery ability following brain damage. However, studies from the 1970s showed strong correlations between subjectively rated mental imagery and social desirability, raising doubts about whether the VVIQ was measuring mental imagery experience, or was measuring a tendency to give a socially desirable answer. Also, Reisberg et al. (2003) reported that researchers who rated themselves as having highly vivid imagery also were more likely than low-scoring researchers to feel that research on mental imagery was an important phenomenon and worth pursuing. Moreover, the VVIQ does not correlate highly with *objective performance measures of visual working memory, such as the ability to recall or recognize novel, abstract patterns presented a few seconds earlier. These and other results point to the suggestion that there might not be a causal link between the phenomenal conscious experience of mental imagery and the functioning of visual working memory. In other words, what people report of their conscious experience of mental images might not reflect any functional aspects of working memory.

A more positive link between conscious visual images and memory came from research showing that lists of words that are rated as being easy to image are remembered much more readily than are lists of words that are low in imagery (e.g. Paivio 1971). Moreover, creating bizarre or unusual images is well known as a technique for improving memory for words. Therefore, there appears to be an advantage in memory for words that are easy to associate with a conscious image for most people. However, these conscious images are generated from information held in long-term memory, and it may be that generation of a conscious image reflects the temporary activation of long-term memory, and not the functioning of working memory. In contrast working memory might be more focused on the retention and manipulation of recently experienced novel material. Indeed, one primary function of working memory might be to deal with novel information that has few, if any associations in long-term memory (for a detailed discussion see Logie 2003).

A possible reason for the lack of a relationship between rated conscious experience of an image and memory performance is the problem of inter-rater calibration of *subjective ratings; one person might rate a particular conscious experience as being highly vivid, but a similar experience might be rated as less vivid by someone else. As such, rating scales for visual mental images might be poor measures of individual differences in the phenomena being rated, even if they are robust and reliable measures within one individual tested on different occasions.

Baddeley and Andrade (2000) approached this problem by examining how subjective ratings of mental images within the same individuals are affected by experimental manipulations. They asked their participants to generate mental images while they performed another task, such as tapping the keys on a 4 × 3 keypad or watching irrelevant random dot patterns. Rated vividness of visual images was reduced by concurrent tapping and by watching random dot patterns. In contrast, memory performance was affected by concurrent tapping but not by random dot patterns.

The disruptive effects of the secondary tasks on rated vividness of imagery were more evident for imaging novel patterns (using working memory) than they were for familiar scenes such as cows grazing, a game of tennis, or a sleeping baby (using long-term memory). This points towards a more direct link between working memory and conscious experience, and because each participant is being compared with themselves, there is not a problem of differences between individuals in the criteria that they use for their vividness rating. However, because memory performance and rated vividness are affected differently by secondary tasks, the suggestion is that conscious experience of visual images might not draw on the same aspects of working memory that are used for temporary visual memory.

One potential problem remains, and that is the possible expectation by the participants that a secondary distractor task will affect their mental operations. Hence, they rate their visual mental images as being less vivid when performing a secondary visual task because they expect their images to be affected in this way. Subtle, unintentional hints from the experimenter in how the instructions are presented could reinforce this expectation. However, participants’ expectations should apply equally for imagery involving long-term memory and imagery involving working memory, given that conscious images are reported in both cases. It was clear from the experiments that the strongest effects appeared for the working memory tasks, and this differential effect for working memory and for long-term memory is less easy to explain in terms of participant expectations, giving more confidence to the conclusion that the experimental manipulations did indeed affect the conscious experience.

Individuals who suffer from a dense anterograde *amnesia appear unable to retain new information for more than a few minutes, and several such patients have described their experience as ‘continually waking from a dream’—their awareness of real events appears to fade in the same way that dreams fade a few moments after we wake in the morning. Such individuals appear to have largely intact working memory functions, and to be aware of what is happening moment to moment. This suggests that whatever is affecting their ability to remember their immediate and more remote past, affects neither their working memory function nor their awareness of what the 19th century philosopher and psychologist William James referred to as ‘the specious present’. Other brain-damaged patients with a rather different cognitive impairment, namely unilateral spatial neglect, appear unaware of one half of their environment (usually on the left) and they also appear to have impairments of visual working memory performance.

Both of the above examples suggest that the functioning of working memory is associated with conscious awareness—current awareness and working memory are both intact in the face of severe amnesia, and damage to working memory function is associated with loss of awareness. However, these are associations, not causal links, and some other cases suggest that the association is less clear: for example, with individuals who report having lost, or never having had the ability to generate mental images. These individuals report being unable to experience any kind of visual mental experience such as imaging the appearance of characters in a radio play, or the visual appearance of a familiar scene or face. They can nevertheless perform well on tests of visual working memory, such as recognizing unfamiliar patterns that they have seen a few moments before, recalling the layout of objects or scenes, or navigating their way around the world (e.g. Botez et al. 1985). That is, memory for visual and spatial information does not necessarily rely on having phenomenal awareness of the visual characteristics of that information.

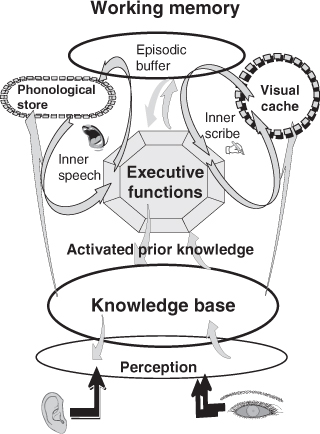

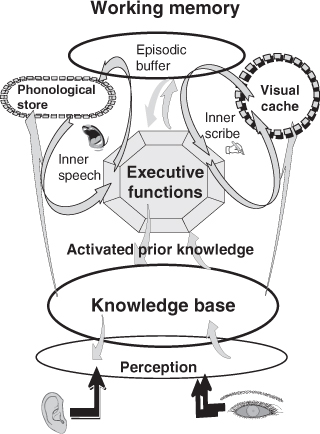

One influential theory of working memory proposes that there are separate components, each with different roles, and there is now a large body of experimental evidence for the characteristics of these components (reviewed in Logie 2003, Baddeley 2007). One of these components, the phonological loop, is thought to support inner speech and the ability to remember and repeat verbal sequences in the correct order, such as a new, multisyllabic word, or a telephone number. A second component, the visual cache, is thought to retain the visual appearance and spatial layout of objects or scenes, allowing us to remember where things are or what they look like, while another component, the inner scribe, helps us remember sequences of movements. A fourth component, referred to as the episodic buffer, is thought to act as a temporary store for integrated information from several modalities and to include semantic information. A fifth consists of what is sometimes referred to as the central executive, now thought to be a collection of ‘executive’ functions, including the control of *attention, of multitasking and task switching, encoding and retrieval strategies, along with higher-order functions such as reasoning and problem solving. The formation of visual images are also seen as executive functions. In a previous version of this framework, a ‘visuospatial sketch pad’ was thought to support visual and movement memory as well as imagery. But it has become clear that the temporary memory (visual cache and inner scribe) and imagery functions are quite distinct. An illustration of a current version of this theory is shown in Fig. W1.

Given the characteristics of these components, the executive functions might, at first glance, be seen as serving consciousness. However, we can also be conscious of repeating numbers to ourself; a function of the phonological loop, not of the central executive. So this is clearly not the whole story. A second possibility is that working memory as a whole offers a cognitive theory of consciousness. However, this too does not quite fit: when we are mentally rehearsing numbers, we are conscious only of the number that we are currently rehearsing, while others in the sequence are held in some non-conscious form, but in a ‘state of readiness’ until they are rehearsed in turn.

Fig. W1. Schematic view of the multicomponent model of working memory. Adapted from Logie (2003).

Baars (1997) has argued that the concept of working memory can be considered as a ‘workspace of the mind’ using the metaphor of a theatre in which the main actor is under a spotlight, to illustrate the focus of attention or of consciousness, while other actors, props, etc. are in the immediate background ready to move into the spotlight when their turn arises. This presumably contrasts with props that are held in the storeroom or possible actors who have not been cast for this play, so are not readily available or needed in the immediate future. This last category of props and actors would offer a metaphor for the vast amount of information held in some form of longer-term memory that would require some effort to retrieve and that is not needed for the current task. Cowan (2005) has demonstrated that the spotlight or focus of attention might be limited to around four items at any one time.

Baars (2002) argued further that consciousness offers a means to integrate information across independent brain functions, by focusing the attentional spotlight on quite different kinds of information from different sources. Evidence for this last conjecture is derived from the now large literature on the use of *functional brain imaging techniques, and Baars (2002) reviews several studies demonstrating that conscious activity appears to be associated with relatively widespread activation across the cortex (hence allowing for integration across these different areas) compared with non-conscious activity. In contrast, studies specifically of working memory components are associated with more focused patterns of activation, for example the operation of the phonological loop is linked with activation in the speech areas (primarily Broca’s area and the supramarginal gyrus) in the left hemisphere. The visual cache is linked with activation in the posterior parietal cortex (Todd and Marois 2004). Executive functions appear to be linked with specific areas in the prefrontal cortex. For example, the ventro-lateral prefrontal cortex appears to be associated with updating and maintaining the contents of working memory while the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is associated with selecting, manipulating and monitoring the contents of working memory (Fletcher and Henson 2001).

The concept of working memory appears to offer a prime candidate for providing a cognitive theory of consciousness. There is evidence for an association, with, for example phenomenal experience of vividness of mental images and immediate memory for unfamiliar visual patterns being affected by some, but not all, of the same experimental manipulations. However, there is relatively limited empirical evidence demonstrating any causal link, and individual differences in subjective ratings of the vividness of visual mental images do not correlate with visual working memory performance. Moreover, some studies have shown that visual working memory can function adequately when participants report having little or no visual phenomenal experience.

Although only a limited range of literature can be reviewed here, it seems clear that working memory cannot be viewed simply as currently activated long-term memory, but is a multi-component system that deals with novel material and can carry out a range of operations including updating, inhibition, transformation, and formation of new associations including mental images, as well as supporting temporary memory. The findings alluded to here illustrate that the possible link between conscious experience and working memory can be studied empirically. Although this link remains unclear, we can at least provide a response to the two questions raised at the start: working memory might fulfil a necessary, but not sufficient prerequisite for consciousness, but consciousness is not a necessary prerequisite for all of working memory function.

ROBERT H. LOGIE

Baars, B. J. (1997). In the Theater of Consciousness: The Workspace of the Mind.

—— (2002). ‘The conscious access hypothesis: origins and recent evidence’. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6.

Baddeley, A. D. (2000). ‘The episodic buffer: a new component of working memory?’ Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4.

—— (2007). Working Memory, Thought and Action.

—— and Andrade, J. (2000). ‘Working memory and the vividness of imagery’. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 129.

Botez, M. I., Olivier, M., Vézina, J-L., Botez, T., and Kaufman, B. (1985). ‘Defective revisualization: dissociation between cognitive and imagistic thought. Case report and short review of the literature’. Cortex, 21.

Cowan, N. (2005). Working Memory Capacity.

Fletcher, P. and Henson, R. (2001). ‘Frontal lobes and human memory: insights from functional neuroimaging’. Brain, 124.

Logie, R. H. (2003). ‘Spatial and visual working memory: a mental workspace’. In Irwin, D.and Ross, B. (eds) Cognitive Vision: The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, Vol. 42.

Marks, D. (1973). ‘Visual imagery differences in the recall of pictures’. British Journal of Psychology, 64.

Miyake, A. and Shah, P. (1999). Models of Working Memory.

Osaka, N., Logie, R.H., and D’Esposito, M. (eds) (2007). The Cognitive Neuroscience of Working Memory.

Paivio, A. (1971). Imagery and Verbal Processes.

Reisberg, D., Pearson, D., and Kosslyn, S. (2003). ‘Intuitions and introspections about imagery: the role of imagery experience in shaping an investigator’s theoretical views’. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 17.

Todd, J. J. and Marois, R. (2004). ‘Capacity limit of visual short-term memory in the human posterior parietal cortex’. Nature, 428.