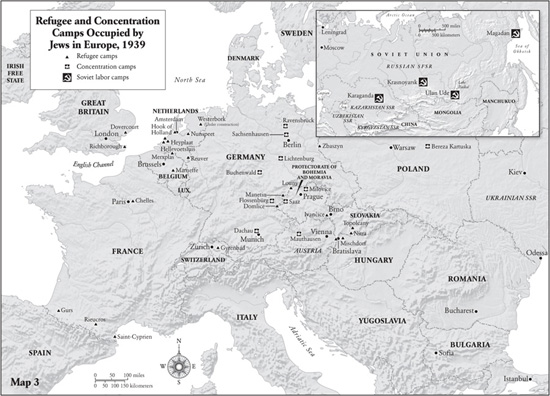

By January 1939 the Jews of Europe were being transformed into a people without fixed abode. All over the continent, Jews, evicted from their homes and homelands, were forced into temporary accommodation in so-called “camps.” Sometimes, as in Germany, these were prisons where they were subjected to slave labor and torture. Elsewhere, as in France, Poland, or the Netherlands, they were places of internment designated for refugees, illegal immigrants, or political undesirables. What all these countries shared was the notion that the camp dwellers did not belong in normal society. The Jews were not alone in these places. In the USSR, selection for incarceration in the labor camp system was almost arbitrary. In Germany any political opponent of the regime might be rounded up. But the Jews, more than any other group in Europe, were already on the way to becoming a “camp people.”

The primary cause was Nazi anti-Semitism. Yet in the late summer of 1939 far more Jews were being held in camps outside the Third Reich than within it, most of them in countries that were subsequently to wage war against Germany.

The first major Nazi concentration camp was established in March 1933 at the site of a disused munitions factory at Dachau, near Munich. In May a twenty-seven-year-old Bamberg attorney, Wilhelm Aron, became one of the first victims of the Nazi camp system. He had been arrested a few weeks earlier “on suspicion of subversive activities” and was reported to have died suddenly in Dachau. The death certificate gave the cause of death as pneumonia. The body was returned to his family in a sealed coffin that “by order of the criminal police … was not to be opened.”1

The two other important prewar Nazi camps were Sachsenhausen, near Berlin, which opened on July 12, 1936, even as preparations for the Olympic Games were in their final stages, and Buchenwald, near Weimar, which opened in 1937.

In the concentration camp system as a whole, until the outbreak of the war, Jewish prisoners constituted a minority of prisoners, save for a period between the spring of 1938 and early 1939. At first the number of prisoners was, by comparison with the wartime period, relatively small: in mid-1935 there were altogether 3,555 inmates in German concentration camps. Until 1938 there were never more than about 2,500 at Dachau. Many times that number, however, passed through the camp as, each year, newcomers were roughly balanced by releases—and deaths. In 1938, 18,000 prisoners were admitted, mainly after the Anschluss and the Kristallnacht, but most of these too were released after a short time so that in the summer of 1939 the camp held about 5,000 people.

Sachsenhausen, the largest concentration camp in the late summer of 1939, contained more than 6,000 prisoners: of these Jews numbered 250, as compared with 360 Jehovah’s Witnesses. The Jewish inmates included political opponents of the Nazis, persons accused of “racial pollution” by virtue of sexual intercourse with non-Jews (many of these were sterilized), so-called asocial elements (including unemployed persons), and returning emigrants sent to camps to undergo “re-education.”2

When Sonia Wachstein’s brother Max disappeared in police custody in the spring of 1938, she went to Gestapo headquarters in Vienna to try to find out what had happened to him. An official told her he had been sent to Dachau. She began to cry. “Why are you carrying on like that?” he said. “Dachau is not a bad place.”3

The organization and regimen of Dachau served as a template for all later Nazi concentration camps (as distinct from the wartime death camps). Upon arrival at Dachau prisoners were lined up and forced to stand and wait for a long time. Their heads were shorn and they were given cold showers. Camp uniforms were distributed: Jews were assigned blue-and-white striped cotton; gentiles had warmer clothing. Then the prisoners were marched off to wooden blockhouse barracks, each with fifty-four straw-covered bunks. When large groups of Jewish prisoners arrived after the Kristallnacht, the arrival procedure was augmented with a preliminary forced running of a gauntlet of SS guards who belabored the prisoners with sticks and seized their money.

A bugle call at six o’clock every morning woke them. At six-thirty there would be a roll call inspection on the main parade ground followed by another one or two later in the day. Some prisoners engaged in specialized work, such as shoemaking, but most Jews were assigned to labor on the camp’s Heilkräuterplantage (herb garden). Apart from bread and ersatz coffee, they received only one meal a day, in the evening: it typically consisted of whale or lentil soup, potatoes served out of large tin cans, a piece of sausage or cheese, or a herring.

Relatives or friends were at first permitted to send parcels or money to prisoners in the camp. But the money was lodged in an account from which the inmate was forbidden to withdraw more than fifteen marks at a time. With this he might buy supplementary rations: salami, cheese, butter, honey, preserves, stationery, cigarettes, or coffee. Since these were priced much higher than in the outside world, the system amounted to an officially sponsored racket. Prisoners could write and receive letters at fixed periods. Both Dachau and Buchenwald boasted a lending library, shown off to impressionable visitors as a sign of the enlightened nature of the system.

Small infractions of rules often resulted in savage punishment. A man who left his socks on the wrong shelf was sentenced to an hour of “tree hanging”—he was suspended by his arms on the branch of a tree, with his toes just above ground level.4 Many prisoners were tortured and some murdered.

Most concentration camp prisoners in the early years were men. But from 1937, Lichtenburg castle at Prettin, near Wittenberg, operated as a camp for women, mainly political enemies of the regime. It was closed in May 1939 and the women sent to Ravensbrück, near the former Mecklenburg health resort of Fürstenberg. Ravensbrück henceforth became the only concentration camp in Germany designated exclusively for women.

Gross overcrowding in the concentration camps in the weeks after the Kristallnacht exacerbated the hardships of the prisoners. In Buchenwald an inmate found himself one of two thousand men in a single barrack: “we had no beds, no soap, hardly any water, no linen. Sanitary conditions were hair-raising.”5

The sudden increase in the camp population in November 1938 affected male Jews all over Germany. The day after the Reichskristallnacht, the SS turned up in strength at the Gross-Breesen training farm and arrested the head of the school, the master carpenter, another instructor, and many older pupils. They were sent to Buchenwald. One of the SS men politely asked the master carpenter for a sledgehammer. When the younger students returned to their rooms later, they found that they had all been smashed up. One of the farmworkers, on orders from the SS, chopped up a Torah scroll into small fragments on a pile of manure.

Hermann Neustadt, one of the arrested students from Gross-Breesen, later recalled his experiences in November–December 1938 in the “special camp” adjacent to the main Buchenwald concentration camp:

When we arrived, the call again, “Ooouuut!” and we had to jump down from the truck and run on the trot over very rough gravel. On both sides stood S.S. men, who struck at us. Those who could not run quickly enough over this rough area of land or even fell down were beaten. In the end, we had to line up in military formation and wait. We waited the next 48 hours! …

We had to sleep on the wooden plank beds and there was neither straw nor any blankets. … During the first nights the S.S. came and took a few people away with them from the barracks, who had apparently been on a special list. What happened to them, I could not see, as I did not dare to get out of my sleeping place. However dogs and screams were heard and that people were beaten. …

We were able to observe, from our “special camp,” which was separated from the rest of the camp by barbwire fences, how prisoners were punished. Some of them were strapped onto the “rack” and then received 10 or 25 strokes with the whip, perhaps even more. Then they were unstrapped and had to stay at attention, else it produced more strokes. … Besides the already mentioned Sergeant Zoellner, who had trod on me, I only remember still one S.S. man Sommer or Somers, who as far as I could see was a rather good-natured fellow.

Although the Gross-Breesener group numbered only about 20, who all knew each other very well, for days we were not able to recognize each other. With heads shaved bare, all of us looked quite different. … The six barracks were built in such manner, that one corner of number 6A stood in the so-called “death-strip,” i.e. that was the strip of levelled off land in front of the electric fence, where under “normal” circumstances, the S.S. guards could shoot the prisoners without a special order, if they believed that they wanted to escape. …6

Neustadt was released after three weeks upon signing an undertaking to leave Germany as soon as possible. He crossed the border on December 15 and made his way to Amsterdam. From there the Amsterdam Jewish Refugees’ Committee dispatched him to the training farm at Wieringen. About the same time the other arrested Gross-Breesen students were released on condition that they too left Germany immediately. With the help of the Amsterdam committee, some moved to Wieringen. Others were admitted to England to work on farms.

But many Jews who had been held in concentration camps could not leave Germany before the end of August 1939.

In the USSR, Jews were not, in principle, more in danger than any other citizens. In strictly statistical terms, indeed, they were under-represented in the Soviet prison camp system. Of 3,066,000 people imprisoned in the Gulag (the acronym formed from the title of the chief administration of camps of the NKVD) in 1939, between 46,000 and 49,000 were Jews, slightly less than their proportion in the population.7 Among the leading figures in the Gulag administration were many Jews, several of whom were themselves ultimately arrested and shot.

Jews’ legal emancipation in Soviet Russia endowed them with a superficial equality, even if only one of fear, in what was no longer, as it had been under the tsars, a Rechtsstaat. But in practice Jews in the 1930s found themselves peculiarly targeted by the Stalinist regime. In 1934 an NKVD circular initiated the process whereby particular ethnic groups, regarded as suspicious, were to be accorded special attention. Germans, Lithuanians, and Poles were among those in the first rank, regarded as hostile to the Soviet Union and excluded from high positions. Jews, together with Armenians and others, were in a second category who were to be closely observed.8 In the prevalent atmosphere of paranoia and spy fever in the late 1930s, persons with foreign connections were particularly prone to fall under suspicion. Jews, with their high degree of urbanization and large number of emigrant relatives, were consequently natural targets.

In June 1937, for example, Grigory Kaminsky was abruptly dismissed from his post as commissar for public health, arrested, and later executed. His brother-in-law, Joseph Rosen, feared that the reason was his connection with the Joint. In his “secret speech” to the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956 and in the memoirs he caused to be published abroad after his retirement, Nikita Khrushchev called Kaminsky “a forthright, sincere person, loyally devoted to the party, a man of uncompromising truthfulness.” Khrushchev related that Kaminsky was arrested immediately after having taken the floor in a central committee meeting to accuse Lavrenty Beria, at that time a rising force in the NKVD, of having collaborated with British intelligence.9 According to another account Kaminsky disappeared after confronting Stalin with the challenge: “If you go [on] like this, we’ll shoot the whole party.”10

Whatever the explanation of Kaminsky’s fall, it immediately endangered all who had had any close connection with him. Of the seventy German doctors whose entry to the USSR he had facilitated, fourteen had been arrested by the following December. Sixty officials of Agro-Joint in the Soviet Union, including all its senior figures, were also arrested and accused of being Trotskyite, Zionist, and/or Nazi agents. Under interrogation they were compelled to confess to criminal contacts. For example, the manager of the Agro-Joint office in Simferopol declared that a group of foreigners who had visited Crimea “under a false pretext of familiarization with the Jewish kolkhozes” had “collected spy information and slanderous materials about economic conditions, population structure, and other information.”11 The accountant of the office was accused of being “a member of the counterrevolutionary, Jewish, bourgeois-nationalistic spy organization created by German intelligence.”12 Most of those arrested were sentenced to long spells in labor camps from which few emerged alive. Several were sentenced to death.

Even the most devoted Jewish Communists, often especially the most devoted, fell victim to the purges. Yitzhak Barzilai, born in Cracow in 1904, had been brought up as a religious Jew and a Zionist. In 1919 he emigrated to Palestine, where he converted to Communism and became one of the founders of the Palestine Communist Party. During the 1920s he roamed the Middle East as a Comintern agent, helping to found Communist parties throughout the region (indigenous Jews were prominent in the nascent Communist movement in countries such as Egypt and Iraq). In 1933, in recognition of his services, he was accorded Soviet citizenship, whereupon he took a new name, Joseph Berger. As head of the Comintern’s Near East department, he entered the USSR’s policy-making elite. But in 1934 he was summarily dismissed and expelled from the party. A year later he was arrested, charged with Trotskyism, and sentenced to five years in a labor camp (the term was later increased to eight). He was sent to Siberia.

Gershon Shapiro was lucky not to share the same fate. He had already survived one purge. In 1932 he was ordered back from Friling to Odessa to take charge of the Yiddish House of Culture there. In the early years after the revolution, Odessa had been an important center of Soviet-style Jewish culture. Yiddish and even Hebrew publishing flourished. There were twelve Yiddish-language schools, several Jewish libraries, and, from 1924 to 1933, the Mendele Moykher Sforim Museum. But by the early 1930s Jewish cultural life in the city was dwindling. Shapiro came to the conclusion that his career should take a different direction. In 1934 he entered the Jewish section of the agricultural institute in Odessa, where he studied for the next five years.

In 1936, however, he got into trouble again following an exchange in a class that he gave in the Odessa party school. Shapiro had explained, in correct Stalinist locutions, that Trotsky was no proletarian revolutionary. A student pointed out that Trotsky had played a major role in the revolutionary movement in Russia. Shapiro replied that that might be so but there were proletarian revolutionaries and petit bourgeois ones: Trotsky belonged to the latter category. Shapiro’s reply was reported to party authorities who interpreted it as an affirmation that Trotsky was, after all, a revolutionary, whereas, according to Stalinist orthodoxy, he was to be consigned to the category of counterrevolutionaries and traitors. A party meeting concluded that Shapiro had been trying to smuggle Trotskyist ideas into his teaching in the party school. Accordingly, he was expelled from the party and forbidden to continue his studies at the institute. Although his exclusion from the party was confirmed by the district party committee, his dismissal from the institute was rescinded. In spite of its partly reassuring aftermath, the incident troubled him. As Stalin’s terror engulfed the Soviet Union, Shapiro began to feel what he later described as “incomprehension and bewilderment.”13

In August 1937, Moshe Zalcman was arrested in Kiev. He had committed no overt act of unorthodoxy and his seizure should probably be seen as part of a broad drive for stricter discipline in the world Communist movement, in which Jews’ prominence now rendered them particular victims. The previous spring the Jewish section of the French Communist Party had been ordered to dissolve. In May–June that year the Executive of the Comintern resolved that Jewish Communists must combat “certain tendencies within their own ranks,” not only “declared Jewish fascists” but also “Jewish nationalists” who were creating “ideological confusion.”14 In the spring of 1938 the heavily Jewish Polish Communist Party was closed altogether on orders from Moscow and many of its leaders who had taken refuge in the USSR disappeared. During these months other foreign Communist refugees in Moscow, among them Béla Kun and others of Jewish origin, were killed.

After interrogation, partly conducted in Yiddish, and torture, Zalcman was told he had been found guilty of espionage and sentenced to ten years’ detention in a labor camp. Only twenty-seven of the forty men crowded with Zalcman, nine to a wagon, survived the six-week train journey to Karaganda in Kazakhstan.

Here was the largest network of slave labor camps in the Soviet Union, with tens of thousands of prisoners. Zalcman was initially assigned to the Central Agricultural Industry Camp, annexed to Karaganda. Conditions were atrocious. Danger lurked on every side—from malevolent guards, criminal overseers, thieves, and informers to extreme temperatures, bedbugs, fleas, and disease of every kind. Even official inspectors sustained prisoners’ complaints against the camp administration, who were reproached for “not being interested in the fate of those persons entrusted to them.”15 But there is no evidence that the inspectors’ reports brought any improvement or, indeed, that anything was done with them besides filing them away in the archives.

In the camp Zalcman met several other Jewish prisoners. Among them was Leyzer Ran from Vilna. Ran had worked in YIVO and was well acquainted with Yiddish literature. In 1936 the Communist Party in Vilna had sent him to study in the USSR but he was arrested immediately upon crossing the frontier, sent to the Lubianka prison in Moscow, and then to Karaganda. Zalcman managed to get himself attached to Ran’s group of prisoners, who formed an eight-man, Yiddish-speaking work brigade. After a few months they were all sent for a new round of interrogation. In response to an NKVD officer who accused him and his Jewish friends of “forming a nationalist group,” Zalcman replied: “Isn’t it normal to seek out a neighbour when one finds oneself abroad. … We can’t help each other much but just hearing one’s mother tongue leaves a good feeling.”16 He and his friends were not punished but were separated. Zalcman was moved to another camp and swallowed up in the maw of the Gulag.

The first concentration camp in Poland was established in 1934 at Bereza Kartuska, near Brest-Litovsk. Political prisoners of every stripe were detained there without trial: originally designed for Ukrainian nationalists and right-wing Polish extremists, it later came to hold many thousands of Polish Communists, of whom a large proportion were Jews. Among them was Leon Pasternak, a young Polish poet and cousin of Boris Pasternak.

By 1939, however, the largest number of Jewish camp detainees in Poland were the involuntary border crossers from Germany who the Poles continued to insist were no longer Polish citizens. After a few weeks of sleeping in stables, some of the deportees were allowed by the Polish authorities to rent rooms, or rather beds in crowded rooms, in the border town of Zbąszyń. The Joint and Polish Jewish relief groups organized rudimentary schooling, clinics, and cultural activities.

Max Weinreich visited Zbąszyń in late November 1938. He reported on the misery that he encountered but also worried about its larger implications: “Is Zbąszyń a passing episode? If not—the heart stops at the thought!”17 Another visitor was the historian Emanuel Ringelblum, who represented the Joint. His report helped galvanize further aid to the refugees. As time went by, however, the flow of charitable support diminished and the position of the refugees became even more desperate.

In early 1939 Germany and Poland came to an agreement about the disposition of the deportees. They were to be allowed to return temporarily to Germany “to wind up their affairs.” What this in effect meant was that they would be despoiled, in pseudo-legal form, of most of their property. What little remained they would be permitted to remove to Poland, which finally agreed to admit them with their families. The Germans did not want all the expellees to return at once: only a few thousand were to be allowed back at any one time, for up to a month each. The encampment at Zbąszyń therefore continued to exist for several months.

In July 1939 there were still at least two thousand refugees there. Meanwhile the Germans were driving additional, smaller groups of Jews across the frontier. A report on a visit to Poland by two representatives of the American Friends Service Committee in late July 1939 described a conversation with a woman at Zbąszyń who, with many others, had been chased into the Polish-German no-man’s-land by German police with dogs. She had set out with two children, one that she carried and another who fell behind. “She was not allowed to go back for it [sic], and the little thing perished in the swamp.”18

Meanwhile, other countries had followed the Polish-German example in forcing Jews into no-man’s-land camps. By January 1939 there were reported to be at least twelve along the German, Slovak, Hungarian, and Polish frontiers. In March, following the German annexation of Memel from Lithuania, Jews fled or were driven out from that small territory. Within three weeks not a single person remained in the enclave out of a former Jewish population of seven thousand. Some found shelter in Kovno. Late arrivals had to camp in the fields near the border town of Kretinga.

The expulsion fever spread to southeast Europe. Yugoslavia started deporting Jewish refugees who had arrived from Germany and Italy. And the Romanian foreign minister announced that “it was necessary in the interest of the Jews themselves as well as in the interest of the country that a part of the Jewish population should emigrate.”19 He later explained that he had been referring only to Jews resident illegally in the country, although, since the government had recently withdrawn the citizenship papers of a large number of Jews, many of these would presumably count as illegal.20 At the end of April the Bulgarian government ordered the expulsion of all alien Jews. About fifteen thousand people were affected, among them some long-term residents of the country. Many were Poles who had been deprived of their nationality.21 Most had nowhere to go.

In western Europe too, refugees found themselves confined to camps, albeit not on the frontier. In Switzerland Jewish organizations in January 1939 were maintaining nine hundred refugees in a dozen camps. In Belgium, where, that winter, refugees were crossing the border from Germany illegally at the rate of four hundred a week, the government set up an “isolation camp” at Merxplas and a training camp at Marneffe in a castle that had formerly served as a Jesuit college. The Merxplas camp was housed in buildings of the state workhouse for vagrants; the refugees, however, were separated from the tramps. The inmates were allowed to visit Brussels for two days every three weeks. They were not permitted to enter the village of Merxplas.

In France, as early as 1934, the director of the Sûreté Nationale had told the press that, given the difficulties involved in expelling undesirable refugees, the only solution to the problem would be to send them to “a concentration camp” where they would be “subjected to hard labor for a fairly long period of time.”22 The idea was shelved for the time being. But by 1939 contrasting pressures of philanthropy and xenophobia produced two different kinds of camps in the country. The eleemosynary impulse led to the creation after the Anschluss of a refugee camp for Austrians at Chelles, near Paris. The residents lodged in a hotel or private houses and ate in a communal refectory. They were free to come and go but could not set up residence in Paris, nor in several neighboring departments. By September 1939, 1,400 refugees, including some from the Spanish Civil War, were living in Chelles.

Meanwhile, bowing to less benign pressures from public opinion, the French government in November 1938 issued a decree envisaging the internment of undesirable aliens, by which was meant primarily Communists. The first camp of this kind opened in the spring of 1939 at Rieucros (near Mende, Lozère) as a “special concentration center” for aliens. These were mainly political refugees, who had been unable to obtain a visa for another country and who were detained “in the interests of order and public security.”23 The sudden implantation of this alien presence in the heart of the French countryside aroused consternation among local people. Mayors and other officials in the neighborhood protested indignantly against the presence of these undesirables. The special commissioner in charge of the camp reported to the departmental prefect that a veritable panic had broken out in the area and that there was talk of setting the camp on fire.24

Five more such camps were, nevertheless, established in France in the course of 1939, all in the Pyrénées-Orientales, for the internment of 226,000 former Republican combatants in the Spanish Civil War who sought refuge in France. Among these were Jewish former soldiers in the International Brigades. At one of these camps, Saint-Cyprien, in April 1939, former combatants of the Botwin Company, mainly Communists from eastern Europe, produced a primitively printed Yiddish paper, Hinter shtekhel droten (Behind Barbed Wire).25 After a few weeks these internees were moved to a camp at Gurs, while the French government tried to find another country that would take them all in. Some were released on enlisting in the French Foreign Legion. About forty thousand, mainly Spaniards, were admitted to Latin American states. A few of the Jews succeeded in escaping from the camps before September 1939. But the Communist Party appears to have disapproved of such escapes as smacking too much of spontaneous initiative. At the outbreak of war many of the Jewish prisoners were still in the camps.

In general, Dutch society accorded the refugees a relatively generous reception but here too there were rumblings of xenophobia and anti-Semitism. Attempting to mediate between immense pressure from potential immigrants and resistance from extreme-right elements, the government decided after the Kristallnacht to admit a limited number of refugees but to quarantine them in an internment camp at the Lloyd Hotel in Zeeburg (east Amsterdam) and at the Heyplaat Quarantine Station in Rotterdam. Camps were also established at Hook of Holland, Reuver, Hellevoetsluis, and Nunspeet. These were internment camps designed for male illegal immigrants and there was an element of punishment in the camp regime. As Bob Moore writes in his history of Dutch refugee policy in this period, these were “bleak places” and “for the majority of respectable refugees who found themselves in these camps, the conditions and their treatment as criminals was a traumatic and harrowing experience.”26

Walter Holländer, Anne Frank’s uncle, who had been arrested during the Kristallnacht in Aachen and sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp but then allowed to leave Germany, was among the internees at Zeeburg. “We were cut off from all contact in this refugee camp and kept under police supervision. We were not allowed—nor was it even possible—to engage in any income-producing work, but we had to pay for our stay in the camp. If I wanted to leave for any reason, I had to obtain written permission from the police officer in charge.”27 In April 1939 Holländer was able, with the help of his brother in the United States, to secure release from Zeeburg on condition that he departed for the United States in December, with the visa and ship’s ticket that he had shown to the Dutch authorities.

In the little walled town of Hellevoetsluis on the Haringvliet (an inlet from the North Sea) in South Holland, the inmates of the refugee camp were guarded by military police. Overcrowding was such that internees were “stuffed like herring in a barrel.”28 Mail was censored and there was little freedom of movement. At first local shopkeepers were reported to be “rubbing their hands” at the prospect of revived trade.29 The atmosphere among the inmates was less jovial. Hardly had the first batch of refugees arrived than one of them, a young “non-Aryan” Christian from Wuppertal, hanged himself.

In the spring of 1939 the minister of the interior refused permission for the refugees to leave the camps briefly to celebrate Passover as the guests of hospitable Jewish families in nearby towns.30 By April 1939 a total of 1,517 refugees were being held in camps in Holland, pending their “transshipment” elsewhere.31

Viewing the problem as a potentially long-term one, the Dutch Interior Ministry initiated work on the establishment of a central camp for both legal and illegal refugees. The chosen site was at Westerbork, a low-lying heath near Assen in the north of the country. The location had originally been designated within the Veluwe national park but Queen Wilhelmina, whose summer palace was nearby, objected, so the government decided on Westerbork instead. The establishment of this central camp “for Jewish refugees only” was supported “with something like real enthusiasm” by the Amsterdam Jewish Refugees’ Committee, which thought that it would provide a temporary “refuge for emigrable people” and a “first-class training centre.”32 Work on construction began in August 1939. Nearby shopkeepers here looked forward to an increase in business. Other local residents complained that their district was being used as a dumping ground for refugees and that it was “common knowledge” that among the potential residents were asocial elements whose motives for fleeing to the Netherlands were other than racial or religious.33

The motives that led to the establishment of camps in Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, Poland, and western Europe were very different in each case, as were the camp regimes. But underlying them all, even those in countries such as France and the Netherlands, was the notion that the inmates did not fit into society and should be kept apart. The camps, indeed, were a microlevel manifestation of a European-wide phenomenon. By early 1939, much of the continent was being transformed into a gigantic concentration camp for Jews. For most of them, life was being made punitively repressive where they were and, at the same time, they were prevented from moving anywhere else. In the lapidary phrase of Chaim Weizmann, in his evidence to the Peel Commission, their world was “divided into places where they cannot live and places they cannot enter.”34

In January 1939 a decree in Romania ordered all commercial and industrial enterprises to report to the minister of national economy the ethnic origin of owners, stockholders, and employees. Efforts to drive the Jews out of the professions accelerated. In Bucharest Emil Dorian confided to his diary that month: “I have been obsessed of late by the idea of a satirical novel, or at least a sad one, based on the present life of Romanian Jews. Its tentative title would be Wanted: Homeland or For Rent: One Homeland, All Facilities Included.”35 Dorian, be it noted, was no Zionist.

A new law in Poland in 1938 made it almost impossible for Jews to enter the legal profession. Employment on the stage (except for the Yiddish theaters) and in the press (except for Jewish papers) was almost completely barred against Jews by 1939. The boycott of Jewish businesses by Poles and Ukrainians intensified. In November 1938 the Jewish Fishmongers’ Association, which supplied 90 percent of fish consumed in the country, reported finding itself under serious challenge by cooperatives that had “set themselves the objective of tearing the fish trade out of Jewish hands.”36 Similar complaints were heard in almost every branch of the Jewish economy.

A report by the central committee of Bundist labor unions in Warsaw in April 1939 provided chapter and verse, industry by industry, of the exclusion of Jewish workers from large areas of employment. Zealous and discriminatory official enforcement of work rules against Jewish bakers, porters, and slaughterhouse workers, for example, was driving Jews out of those trades. The report concluded gloomily: “It does not take the same form in all trades—in some it is faster, in others slower—but everywhere the Jewish worker is under severe pressure.”37

In 1938 a cabaret skit by the Yiddish comedian Szymon Dzigan, titled “The Last Jew in Poland,” took its theme from Bettauer’s novel about a Judenrein Vienna and portrayed Polish officials and citizens, after the entire Jewish population had emigrated, begging the last Jew to remain in the country. The sketch led to a summons from the censors. That the unimaginable was being imagined was evidently unacceptable.

In Hungary political debate over a new anti-Jewish law was temporarily suspended in February 1939 when the right-wing prime minister Béla Imrédy was forced to resign after it was revealed that he himself had a Jewish great-grandmother. His successor, the Transylvanian aristocrat Count Pál Teleki, however, persisted with the legislation. The president of the House of Magnates (upper chamber), Count Gyula Karolyi, a former prime minister, resigned in protest, but the bill took effect in May 1939. The new law differed from earlier legislation in adopting a racial rather than a religious definition of Jewishness. It severely curtailed Jewish economic activity and civil rights, restricted Jewish participation in the professions, and required the dismissal of Jewish civil servants, theater directors, and editors of the general press. Only those Jews whose ancestors had lived in the country before 1867 retained the vote. The 7,500 foreign Jews in the country were ordered to leave.

The German occupation of Prague on March 15, 1939, and the resultant elimination of what remained of Czech sovereignty brought all the Jews of Bohemia and Moravia under direct Nazi rule. Refugees from Germany who failed to escape in time were arrested in large numbers. Anti-Jewish measures, similar to those in the Reich, were extended to the “Protectorate.” Jewish officials were dismissed, Jewish property “Aryanized,” Jewish pupils expelled from German-language schools, Jews excluded from public baths, parks, and theaters. “Hauptsturmfuehrer Eichmann, who worked in this field in Vienna,” was reported to have arrived in Prague to take charge of the organization of Jewish emigration.38

Czech Jews joined those of Germany and Austria in a stampede for the exit. As in the Reich, potential emigrants had to navigate an elaborate bureaucratic maze of forms, attestations, property declarations, visas, and travel arrangements, starting with a four-page questionnaire, with twenty-six supplementary questionnaires (a separate set for each family member) and continuing with interviews at the Jewish community, government offices, consulates and so on.

In Slovakia, now nominally independent under a pro-German, clerico-nationalist puppet régime, decree laws eliminated Jews from the bar, the civil service, and the medical profession. Jewish pupils were excluded from public schools. Militiamen broke into Jewish homes and plundered them. Jews were beaten and tortured. Thousands fled to Poland. Those who managed to evade border controls were looked after by charitable organizations in Cracow and Katowice but were liable to arrest and deportation as illegal immigrants.

In several countries, notably Poland and Romania, restrictions were placed on the right of Jews to acquire land, whether for new houses or for institutions such as schools. In Latvia, where Jews were being forced out of commerce, the professions, universities, and government jobs, a report to the Joint in May 1939 stated that “the Jewish population has become terribly depressed and has fallen into a kind of apathy.”39

The vise was also tightening around Jews in Italy. Three more anti-Jewish decree laws were promulgated in June–July 1939. Jewish military officers were dismissed. Jews were banned from membership of the Fascist Party (enrollment was a requirement for many forms of employment or advancement). Jews were now supposed not to employ non-Jewish servants. School textbooks by Jews were banned. They were expelled from clubs. Jewish children were excluded from public schools. Jewish businesses were closed or subjected to restrictions. Newspapers were forbidden to publish death notices of Jews. La Scala opera house was closed to them. Although the anti-Jewish laws and regulations were only sporadically enforced and could often be avoided by subterfuges or bribes, Jews felt increasing social isolation and vulnerability.

In the early months of 1939 thousands of refugees converged on the Romanian port of Constantţa on the Black Sea, many of them sailing down the Danube on pleasure steamers. Others traveled on sealed trains from the Romanian frontier. The refugees from the Third Reich included former concentration camp inmates. They hoped to make their way as illegal immigrants to Palestine. Some held phony South American entry visas. Many had been sold tickets by Zionist agents or commercial racketeers but upon arrival in Constantţa found that bribes were required to make further progress. One large group was lodging in a cellar near the port. There was fighting to get on board ships.

According to a Zionist intelligence report in July 1939, the German chancellor’s office had issued an order that illegal immigration of Jews to Palestine was to be facilitated by all possible means.40 But the British government did everything it could to try to block such traffic. The Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) monitored ships carrying refugees from Black Sea ports through the Dardanelles. British diplomats pressed the Romanian, Bulgarian, and other governments to prevent passage of Jewish refugees. Those who surmounted the blockade and reached the shore of Palestine faced an unfriendly welcome.

One group of several hundred refugees arrived in early 1939 aboard a dilapidated Greek freighter, the Agios Nikolaios. When the ship arrived off the Palestinian coast, it was met by a British warship, which ordered it to stop. The captain ignored the order and turned back to sea. A warning shot was fired and when the ship still refused to halt, a second shot struck amidships, causing one death and leaving a hole in the hull. The listing vessel limped back across the Mediterranean to Athens, where the Greek government allowed it to remain while repairs were made. The passengers were forbidden to disembark but were provided with food and supplies by the local Jewish community. After it turned out that the Agios Nikolaios could not be made seaworthy with the passengers on board, the Athens community chartered another ship, whose captain agreed to take the refugees to the edge of Palestinian territorial waters. He would not go any further for fear of arrest by the British naval patrol. The ship therefore towed a barge that would be used to transfer the passengers to the shore. In mid-July, after a journey that for many of them had lasted almost five months from their original departure points, they eventually succeeded in landing in Palestine, where they were promptly installed in a quarantine camp at Athlit, near Haifa.41

As doors everywhere slammed shut, the search for some haven of safety became ever more frantic. Eyes focused on the most bizarre and exotic locations. The International Settlement in Shanghai was almost the only place on earth that required no entry visa. Moreover, as the leaders of one of the main German-Jewish organizations pointed out in February 1939, it was “possible to keep a person in Shanghai more cheaply than in any other civilized place we know of.”42 The Jewish organizations outside Germany disapproved of emigration to Shanghai, pointing out that “the situation in that City has become quite desperate.”43 But in default of any alternative, thousands of German and central European Jews set out on the long sea voyage to the Far East.

By the summer of 1939 at least eighteen thousand Jewish refugees from central Europe had reached Shanghai. What amounted to a refugee camp developed in the slum tenements of the Japanese-occupied Hongkew district in the International Settlement. The arrival of this penniless horde, however, provoked a local reaction. In August 1939 the Japanese naval authorities let it be known that “whilst displaying genuine sympathy with European refugees” they were obliged “owing to lack of accommodation … not to permit further refugees to reside in Hongkew after the end of this month.” As a result the Jewish refugee organizations called an immediate halt to all Jewish emigration to Shanghai.44 In the event, individuals, acting on their own initiative in defiance of such instructions, continued to head for the Far East. But the difficulties and costs of getting there mounted and even this improbable refuge became, for most, unattainable.

Surveying the prospects for the Jews in Europe in a long internal memorandum in March 1939, Morris Troper, head of the Paris office of the Joint Distribution Committee, referred to the impossible dilemmas that confronted his organization in trying to allocate its limited funds. In Germany alone, the Joint’s expenditure in the previous month had been 1,185,639 Reichsmarks as against an income of just RM274,354.45 Troper rejected the view that “since the majority of Jews are doomed … all resources must be turned towards the safeguarding of those who still have some measure of protection.” Instead he advocated continuing efforts toward “the salvaging of thousands upon thousands of lives.” And he continued: “One can hardly compare the situation to the attempt to save part of a burning building, for the destruction of part of a people carries with it moral and spiritual consequences so devastating as to shake the very foundation of their coreligionists wherever they may exist.”46