In the twenty-first century, the United States entered a new age of partisanship. Sharp party divisions now characterize all of the nation’s major political institutions. In Congress, the ideological divide between Democrats and Republicans in both the House and the Senate is larger than at any time in the past century.1 Party unity on roll-call votes has increased dramatically in both chambers since the 1970s.2 On the Supreme Court, the justices now divide along party lines on major cases with greater frequency than at any time in decades.3 In many of the states, Democrats and Republicans are even more deeply divided along ideological lines than they are in Congress.4

It has become obvious to both scholarly and non-scholarly observers that partisan conflict among political elites has greatly intensified. What is not as widely acknowledged is that polarization is not confined to the elites. The American people—especially those who actively participate in politics—have also become polarized. Partisan polarization among political elites cannot be understood unless we take into account the parallel rise in polarization in the public as a whole.

The central argument of this book is that this polarization is not an elite phenomenon. Its causes can be found in dramatic changes in American society and culture that have divided the public into opposing camps—those who welcome those changes and those who feel threatened by them. This growing division within the public expresses itself in many parallel rifts—racial and ethnic, religious, cultural, geographic—and it has produced an electorate that is increasingly mistrustful of anyone in the other camp. Democratic and Republican elites are hostile toward members of the other party primarily because Democratic and Republican voters are hostile toward members of the other party. This mutual hostility and mistrust reached new heights in the extraordinarily bitter and divisive election of 2016, and even greater heights with the ascension of Donald Trump to the presidency.

These extremes of partisan behavior appear on almost every measure political scientists can devise. Among all types of party supporters—strong identifiers, weak identifiers, and leaning independents—party loyalty and straight-ticket voting in 2012 reached their highest levels in at least sixty years. According to data from the American National Election Study (ANES) of 2012, 91 percent of a party’s supporters voted for their party’s presidential candidate. That tied the record first set in 2004 and matched in 2008. The 90 percent rate of party loyalty in the House elections of 2012 tied the record set in 1956, and the 89 percent rate of party loyalty in the Senate elections the same year broke the previous record of 88 percent, set in 1958. Unsurprisingly, these rates of party loyalty were accompanied by very high levels of straight-ticket voting. The 89 percent rate of straight-ticket voting in the presidential and House elections in 2012 broke the record of 87 percent set in 1952, and the 90 percent rate of straight-ticket voting in the presidential and Senate elections in 2012 broke the record of 89 percent set in 1960. These extraordinarily high rates of party loyalty continue a trend that has been evident since partisanship reached a low point in the 1970s and ’80s.5

A related measure is how consistently party supporters and independents who lean toward one or the other party vote for their party’s candidates for president, Senate, and U.S. House of Representatives in the same election. According to data from the ANES cumulative file, the proportion voting this way has increased dramatically since the 1970s. Among all party supporters, the rate of consistent loyalty in 2012 was an all-time record, at 81 percent, breaking the record of 79 percent set in 1960. This represented a sharp increase from the loyalty rates of 55 to 63 percent among all party supporters between 1972 and 1988. Republicans had a 79 percent rate of consistent loyalty in 2012, which was somewhat lower than their loyalty rates in 1952, 1956, and 1960, but substantially higher than the rates of the 1970s and 1980s. Democrats had an 84 percent rate of consistent loyalty in 2012, which was the highest ever seen in an ANES survey, easily surpassing the 80 percent recorded in 2004. And party loyalty has increased sharply among all types of partisans—more, in fact, among weak identifiers and leaning independents than among strong identifiers. Between 1980 and 2012, consistent loyalty rose from 71 percent to 89 percent among strong party identifiers, from 47 percent to 74 percent among weak party identifiers, and from 46 percent to 74 percent among leaning independents.

These trends appear to have continued in 2016 despite extraordinarily high negative ratings for both presidential candidates and despite the fact that the Republican nominee had been bitterly opposed by many prominent Republican Party leaders and office holders during the primary campaign. According to data from the national exit poll, over 90 percent of Democratic identifiers voted for Hillary Clinton, and over 90 percent of Republican identifiers voted for Donald Trump. Well over 90 percent of Clinton voters supported a Democratic candidate for the U.S. House, and well over 90 percent of Trump voters supported a Republican House candidate.

Despite their partisan behavior, Americans seem increasingly unwilling to acknowledge any attachment to a political party. In the 2012 ANES survey, only 63 percent of voters identified as either Democrats or Republicans—the lowest percentage of party identifiers in the survey’s history. Between 1952 and 1964, about 80 percent of voters identified with one of the two major parties. Even during the 1970s and 1980s, when party loyalty in voting was at its nadir, the percentage of party identifiers never fell below 66 percent. Moreover, the ANES surveys are not alone in picking up this trend. The Gallup Poll, using a slightly different question, also reports a substantial increase in the proportion of Americans calling themselves independents.6

It appears that many American voters today are reluctant to claim any affiliation with a political party. This may reflect a kind of social desirability effect. Because partisanship has a negative connotation, the independent label appeals to many voters: being an independent means thinking for oneself rather than voting blindly for one political party. However, when pressed about their party preference, most of these “independents” make it clear that they usually lean toward one of the two major parties. In recent elections, only about 12 percent of Americans have fallen into the “pure independent” category, and these people are much less interested in politics and much less likely to vote than independent leaners. When we shift our focus from partisan identification to partisan behavior, we find that leaning independents as well as strong and weak party identifiers are voting more along party lines than at any time in the past half century.

This surge in partisan behavior reflects a fundamental change in political identity in the American electorate, one not adequately captured by conventional measures of party identification: the rise of negative partisanship. Over the past two decades, the proportion of party supporters (including leaning independents) who have strongly negative feelings toward the opposing party has risen sharply. A growing number of Americans have been voting against the opposing party rather than for their own.

The rise of negative partisanship has brought a sharp increase in party loyalty at all levels, a concurrent increase in straight-ticket voting, and a growing connection between the results of presidential elections and those farther down the ballot. More than at any time since World War II, electoral results below the presidential level reflect the results of presidential elections.7

Over the past several decades, as partisan identities have become increasingly aligned with other social and political divisions, supporters of each party have come to perceive the other party’s supporters as very different from themselves in values and social characteristics as well as political beliefs. This perception has reinforced their strongly negative opinions of the other party’s elected officials, candidates, and supporters.8 Such negative perceptions are further aggravated by partisan news sources.9

Favorability ratings by party supporters toward their own party and the opposing party, as reported in the ANES surveys, can be plotted graphically on a “feeling thermometer” scale. The feeling thermometer ranges from zero degrees, the most negative rating, to 100 degrees, the most positive. A rating of 50 is considered neutral. Since they were first asked the question, party supporters’ ratings of their own party have changed very little, moving from 71 degrees in 1978 to 70 degrees in 2012 (figure 1.1). But voters’ ratings of the opposing party have fallen sharply, from 47 degrees in 1978 to 30 in 2012. Moreover, this increasing negativity affected all types of party supporters. Between 1978 and 2012 the mean rating of the opposing party on the feeling thermometer scale fell from 41 degrees to 24 among strong party identifiers, from 50 to 36 among weak party identifiers, and from 51 to 35 among leaning independents. In 1978, 63 percent of voters gave the opposing party a neutral or positive rating while only 19 percent gave the opposing party a rating of 30 degrees or lower. By 2012, only 26 percent of voters rated the opposing party as neutral or positive, while 56 percent gave it a rating of 30 degrees or lower.

Figure 1.1. Ratings of Own Party and Opposing Party on Feeling Thermometer, 1978–2012. Source: ANES Cumulative File

Most of the shift toward negative partisanship has taken place since 2000. In the twelve years between 2000 and 2012 the proportion of positive partisans (voters who liked their own party more than they disliked the opposing party) fell from 61 percent to 38 percent, while the proportion of negative partisans (those who disliked the opposing party more than they liked their own) rose from 20 percent to 42 percent.10 In 2012, for the first time since the ANES began asking the party feeling thermometer question, negative partisans outnumbered positive partisans.

Negative partisanship influences feelings about the presidential candidates as well. Over the past several decades, voters’ ratings of their own party’s presidential candidate have remained fairly steady, generally in the 70–75 degree range on the feeling thermometer. However, their ratings of the opposing party’s candidate have declined sharply. In 1968, the first time the ANES asked for feeling thermometer ratings of presidential candidates, 51 percent of voters gave the opposing party’s candidate a positive rating while only 19 percent gave him a rating of 30 degrees or lower. In 2012, only 15 percent of voters gave the opposing party’s presidential candidate a positive rating; 60 percent rated him 30 degrees or lower.

These negative feelings only increased in 2016. According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center between September 27 and October 10, 2016, Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents gave Donald Trump a mean rating of just 10 degrees on the feeling thermometer. Fully 85 percent of Democrats gave Trump a rating below 50 degrees, with 77 percent rating him below 25 degrees on the 0–100 scale. Fifty-eight percent gave him a rating of zero. Likewise, Republican and Republican-leaning voters gave Clinton an average rating of 11 degrees. The vast majority of Republicans rated her below 25 degrees, including 56 percent who gave her a rating of zero.11

The rise of negative partisanship, and the growing divide between Democrats and Republicans that it represents, have come alongside other, deeper divisions in American society: a racial divide between a shrinking white majority and a rapidly growing nonwhite minority, an ideological divide over the proper role and size of government, and a cultural divide over values, morality, and lifestyles. The past two decades have also seen the emergence of a large generational divide in American politics, because younger Americans are both more racially diverse and more liberal on social and cultural issues than older Americans. These deeper divides in American society have increased the disdain among each party’s supporters for the supporters and leaders of the opposing party.

Perhaps the most important of these three divides is the one over race. Despite dramatic progress in recent decades, race and ethnicity still powerfully influence many aspects of American society, from housing patterns and educational opportunities to jobs and health care.12 Moreover, since the 1980s, the racial divide has increasingly affected the American party system because of how racially conservative white voters have reacted to the growing racial and ethnic diversity of American society.13

Higher birth rates among nonwhites and high levels of immigration from Latin America and Asia have combined to create a steady increase in the nonwhite share of the U.S. population. This demographic shift has altered the racial composition of the American electorate as well, although at a slower rate due to nonwhites’ lower levels of citizenship, voter registration, and turnout.14 Nevertheless, between 1992 and 2008 the nonwhite share of the electorate doubled, from 13 percent to 26 percent. And contrary to the expectations of some conservative pundits and Republican strategists, the trend continued in 2012, with African-Americans, Hispanics, Asian-Americans, and other nonwhites making up a record 28 percent of the electorate, according to both the national exit poll and the 2012 ANES.15 In 2016, according to the national exit poll, nonwhites made up 29 percent of the electorate.

As the nonwhite share of the electorate has grown, so has the racial divide between the Democratic and Republican coalitions. According to national exit poll data, between 1992 and 2016, the nonwhite share of Republican voters rose from 6 percent to 12 percent, while the nonwhite share of Democratic voters went from 21 percent to 45 percent. Data from the 2016 ANES show that this trend is almost certain to continue: the youngest members of the electorate are far more diverse than the oldest. According to the ANES data, nonwhites made up 39 percent of eligible voters under age thirty, compared with only 17 percent of eligible voters over seventy.

The racial divide between party coalitions has not been confined to presidential voters; it was just as large among voters in the U.S. House elections of 2016. In addition, the Democratic Party’s growing dependence on nonwhite voters has contributed to the flight of racially and economically conservative white voters to the GOP, further widening the racial divide between the party coalitions. We will see that this growing racial divide set the stage for the rise of Donald Trump, who appealed to white racial resentment more openly than any major-party nominee in the postwar era.

The Democrats’ growing dependence on nonwhite voters and the flight of conservative whites to the Republicans have also contributed to the parties’ growing ideological divide. Since at least the New Deal era, Democrats and Republicans have disagreed on the proper role and size of government. In recent years that ideological divide has widened, due mainly to the rightward drift of the GOP.16

The sharp partisan difference over the proper role of government was very evident in the 2012 and 2016 electorates. Data from the 2012 national exit poll show that 74 percent of Obama voters favored a more active role for the government in solving social problems, while 84 percent of Romney voters thought the government was already doing too many things that should be left to private individuals or businesses. Eighty-four percent of Obama voters wanted the Affordable Care Act preserved or expanded, while 89 percent of Romney voters wanted it partially or completely repealed. Finally, 83 percent of Obama voters favored increasing taxes on households with incomes over $250,000, compared with only 42 percent of Romney voters.17 The results were very similar in 2016. According to national exit poll data, 75 percent of Clinton voters favored a more active role for the government in solving national problems and 87 percent wanted to see Obamacare maintained or expanded. In contrast, 78 percent of Trump voters favored a less active government role and 84 percent wanted Obamacare reduced in scope or eliminated.

The cultural divide is the most recent source of difference between the parties, having begun to emerge only in the 1970s. Today, deeply felt moral and religious beliefs and lifestyle choices also make for a sharp contrast between Republicans and Democrats.18 Building on a growing alliance with religious conservatives of all faiths and evangelical Protestants in particular, the Republican Party has become increasingly associated with policies that include restrictions on access to abortion and opposition to same-sex marriage and other legal rights for homosexuals. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party has gradually shifted to the left on these issues, perhaps most notably when President Obama himself finally announced his support for legalization of same-sex marriage in 2012.

Although the 2012 election was supposed to be all about jobs and the economy, cultural issues played a significant role. According to the national exit poll, white born-again or evangelical Christians made up 26 percent of the electorate, and despite any reservations they may have had about supporting a Mormon, they voted for Mitt Romney over Barack Obama by 78 percent to 21 percent. On the other hand, those who described their religious affiliation as “something else” or “none” made up 19 percent of the electorate, and they voted for Obama over Romney by an almost equally overwhelming margin, 72 percent to 25 percent. The 5 percent of voters who identified themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual supported Obama over Romney by 76 percent to 22 percent.

Just as on economic issues, Obama and Romney voters were sharply divided on cultural questions. Fully 84 percent of Obama voters wanted abortion to remain legal under all or most conditions, while 60 percent of Romney voters wanted to make it illegal under all or most conditions. More than three-quarters of Obama voters favored legalizing same-sex marriage in their own state, compared with only 26 percent of Romney voters.

Cultural issues contributed to two other striking voting patterns in 2012—the marriage gap and the generation gap. Unmarried voters and younger voters generally have more liberal cultural views than married and older voters. This helps explain the large gap in candidate preference between married and unmarried voters regardless of sex, and the large gap between voters under thirty and those sixty-five or older. According to the national exit poll, 60 percent of married men and 53 percent of married women voted for Romney, while 56 percent of unmarried men and 67 percent of unmarried women voted for Obama. Similarly, 60 percent of those under the age of thirty voted for Obama while 56 percent of those sixty-five or older voted for Romney.

The same patterns were clearly evident in 2016. According to data from the national exit poll, white born-again or evangelical voters favored Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton by 80 percent to 16 percent, while gay and lesbian voters favored Clinton over Trump by 77 percent to 14 percent. Similarly, according to data from the 2016 American National Election Study, voters who favored either an outright ban or very strict limits on access to abortion favored Trump over Clinton by 78 percent to 15 percent, while those who viewed abortion as a matter of personal choice for women favored Clinton over Trump by 61 percent to 31 percent.

These divisions within the American electorate reflect dramatic changes in American society and culture since the 1960s. While political leaders have shaped voters’ responses to these developments, they have not driven these responses or created the political landscape in which they themselves operate. The truth is the opposite: the country’s radical social transformation has reshaped the Democratic and Republican electoral coalitions.

This transformation has included the civil rights revolution, the expansion of the regulatory and welfare state that was first created during the New Deal era, large-scale immigration from Latin America and Asia, the changing role of women, the changing structure of the American family, the women’s rights and gay rights movements, and changing religious beliefs and practices. Compared with American society in the mid-twentieth century, the early twenty-first century version is much more racially and ethnically diverse, more dependent on government benefits, more sexually liberated, more religiously diverse, and more secular. It is also much more divided, and more bitterly divided, along party lines.

In general, Americans can be sorted into two camps: those who view the past half-century’s changes as having mainly positive effects on their lives and on American society, and those who view the effects of these changes as mainly negative. Since the 1960s, Americans in the first group have increasingly come to support the Democrats, while those in the second group have increasingly come to support the Republicans. That, in a nutshell, is what has driven the realignment that has drastically remade the Democratic and Republican electoral coalitions.

The Democratic Party now draws its strongest support from the groups with the most positive views of recent social and cultural changes. These include nonwhites, immigrants, younger voters, single women, gays and lesbians, religious liberals, secular voters, those with a post-college education, and supporters of activist government. The Republican Party draws its strongest support from the groups with the most negative views of the same social and cultural changes. These groups are overwhelmingly white, and among whites, the Republican Party’s strongest supporters today are older voters, evangelical Protestants and other religious conservatives, those without a college degree, and opponents of activist government.

Donald Trump’s campaign slogan in 2016, “Make America Great Again,” was aimed squarely at the latter group of voters. He promised to turn back the clock to a time when members of that group enjoyed greater influence and respect. In his campaign rhetoric and in his inaugural address, Trump constantly painted a portrait of a nation in steep decline—decline which only he could reverse. He repeatedly claimed, without evidence, that the unemployment rate in the United States was far higher than government statistics indicated, that violent crime in the nation’s inner cities was soaring, and that the quality of most Americans’ health care had deteriorated badly since the adoption of the Affordable Care Act. He portrayed Islamic terrorism as a dire threat to the lives of ordinary Americans, even though very few Americans had actually been killed or injured in Islamist terrorist attacks since 9/11.19

According to a survey conducted in August 2016 by the Pew Research Center, a large majority of Trump’s supporters shared his dark vision of the nation’s condition and direction. Fully 81 percent of Trump supporters—compared with only 19 percent of Clinton supporters—believed that “life for people like them” had gotten worse in the past fifty years.20 Moreover, the deep pessimism of Trump’s supporters appears to have been based largely on unhappiness with the nation’s changing demographics and values. Trump’s appeals to racial resentment and xenophobia resonated with a large proportion of less-educated white voters who were uncomfortable with the increasing diversity of American society. Likewise, his promise to appoint conservative judges who would limit the rights of gays and lesbians and curtail access to abortion appealed to religious conservatives upset with the American public’s growing liberalism on cultural issues. However, the message that was so welcome to large numbers of white working-class voters turned off overwhelming majorities of African-Americans, Latinos, Asian-Americans, and LGBT voters, along with many white college graduates, especially women, who benefited from and welcomed these changes.

In some cases, these social and cultural changes reinforced existing cleavages within the electorate; in other cases, they produced new cleavages. Democrats and Republicans have differed over the proper role and size of government since at least the 1930s, but this divide has deepened with the expansion of federal environmental, workplace, and consumer regulations and the creation of benefit programs such as food stamps, Medicare, Medicaid, and, most recently, Obamacare. The partisan differences over racial issues began to develop in the 1960s, when the old southern wing of the Democratic Party began defecting to the Republican side in response to the Democrats’ support for the civil rights movement. Before then, both parties had been divided over racial equality—the Democrats perhaps more than the Republicans. Differences over cultural issues are even more recent, having first arisen in response to the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade, which made abortion legal throughout the nation. The fight over abortion rights quickly became the template for other battles over changing societal norms and women’s and gay people’s demands for equality under the law—again, with Republicans and Democrats lining up on opposite sides with increasing uniformity.

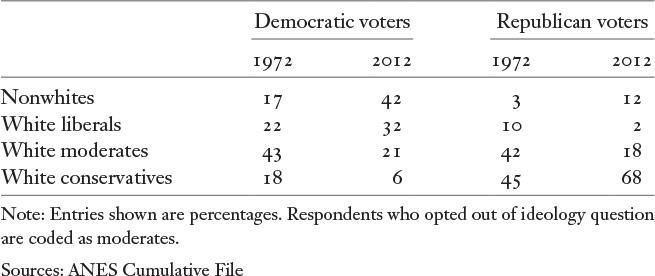

TABLE 1.1. DIVERGING ELECTORAL COALITIONS, 1972–2012

What is striking in American politics today is the extent to which divisions on economic, racial, and cultural issues reinforce each other. Over the past several decades, racial, ideological, and cultural divisions in American society have created a growing divide between the electoral coalitions supporting the two major parties. Comparing the racial and ideological composition of the Democratic and Republican electoral coalitions in 1972 and 2012 shows very clearly that, in terms of race and ideology, the two coalitions have become much more distinct than they were forty years earlier (table 1.1). The contrast would undoubtedly be even greater if our data went back further, but unfortunately, the ANES survey used to gather this information from voters did not ask about respondents’ ideology until 1972. We do, however, have data from ANES surveys on race and partisanship from the 1950s, and they show only a minimal racial divide between the party coalitions: whites made up 93 percent of Democratic voters and 97 percent of Republican voters.

Since the 1970s, both parties’ electoral coalitions have changed dramatically. In 1972, white conservatives made up less than half of all Republican voters, and they barely outnumbered white moderates. Moderate plus liberal whites actually outnumbered conservative whites among Republican voters. By 2012, conservative whites made up more than two-thirds of Republican voters, greatly outnumbering moderate and liberal whites combined. The Republican Party’s electoral base is thus much more conservative today than it was in 1972. In addition, while nonwhites form a slightly larger proportion of GOP voters today than they did in 1972, they remain a very small minority of Republican voters despite the dramatic increase in the minority share of the overall electorate.

African-Americans made up only one percent of Republican voters in 2012, compared with 23 percent of Democratic voters. Moreover, although nonwhite Republicans are somewhat more moderate than white Republicans, they are much more conservative than nonwhite Democrats. According to the 2012 ANES survey, 66 percent of nonwhite Republican voters described themselves as conservative, versus only 15 percent of nonwhite Democratic voters. Nonwhite Republicans were only slightly less conservative than white Republicans, and their presence in the party has very little impact on the overall conservatism of the modern GOP base.

The Democratic coalition has also undergone a makeover since 1972. In the case of the Democrats, the result has been to increase the influence of nonwhites and white liberals at the expense of moderate-to-conservative whites. In 1972, moderate-to-conservative whites made up about three-fifths of Democratic voters, but in 2012, they made up only about one-fourth of Democratic voters. Nonwhites and white liberals dominate today’s Democratic coalition. While these two groups together made up only about two-fifths of Democratic voters in 1972, by 2012 they were about three-fourths of Democratic voters. Because of these changes, the center of gravity of the Democratic Party has shifted considerably to the left since the 1970s.

These changes in the Democratic and Republican coalitions have produced major shifts in how each party’s supporters view those on the other side. To a much greater extent than thirty or forty years ago, Democrats and Republicans today see those who support the other party as very different from themselves, not only in their social characteristics and policy preferences but in their fundamental values. Ordinary Democrats and Republicans increasingly think the other party’s supporters and leaders have questionable motives and pursue goals that would do grave harm to the country. According to a 2014 survey by the Pew Research Center, 27 percent of Democratic identifiers and leaners and 36 percent of Republican identifiers and leaners considered the opposing party “a threat to the nation.” The hostility was even more intense among the most politically active party supporters—54 percent of Republican campaign contributors and 46 percent of Democratic campaign contributors thought of the opposing party as a threat to the nation.21

In every major political institution and at every level of government, the intensity of partisan conflict has increased dramatically, with major consequences for governance and public policy. In Washington, partisan polarization combined with divided party control has led to a politics of confrontation and gridlock. A growing number of state governments, meanwhile, are controlled by one party, with the result that Republican and Democratic states have moved in opposing directions on issues ranging from abortion and gun control to marriage equality and Medicaid expansion. It is no accident that some of the strongest resistance to the Trump administration’s early decisions came from Democratic governors and attorneys general.

Every party system builds on the one that preceded it. In order to understand the contemporary American party system, we must understand its predecessor and the forces that led to its collapse. In the next chapter, I will examine the demise of the New Deal party system forged by Franklin D. Roosevelt during the 1930s, which dominated American politics for more than thirty years. Roosevelt’s electoral coalition was based on three major pillars: the white South, the heavily unionized northern white working class, and northern white ethnics. What united these groups politically was that they all benefited from FDR’s New Deal policies.22 After World War II, however, this coalition began to fracture under the impact of two dramatic changes in American society—the rise of a mass middle class, which turned many previous have-nots into people with a modicum of wealth, and the civil rights movement and consequent growth of the African-American electorate.