2

“In the Land of Ambition and Success”

For the past twenty years or so, I’ve been teaching a course at Georgetown on the literature of New York City. We start off with The House of Mirth, Edith Wharton’s 1905 masterpiece about a woman tumbling down the social ladder, and we read our way through the twentieth century to post-9/11 novels like Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland, the best of the many fictional reworkings of The Great Gatsby. My students also watch classic New York films (A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, On the Town, Annie Hall), read some urban history and sociology, and go on a one-day field trip to New York to “read the living text of the city”—which translates into taking a walking tour through the Lower East Side, Little Italy, and Chinatown and eating lots of knishes, cannoli, and soup dumplings. And, of course, we read Gatsby, one of the first Great American Novels to be set in a city.

Ever since I began teaching it, New York Stories has been the most popular course in Georgetown’s English Department. Naturally, my charisma as a teacher must be the reason, but a contributing factor is New York City itself. My students are fascinated by—and often a little afraid of—New York. Every year, roughly 80 percent of them say they want to move to the city after they graduate. New York is still the place to go to test yourself, especially when you’re young.

That’s certainly how Fitzgerald felt back in 1919. He was twenty-two years old and determined to make it in New York City, just like my students today. It wasn’t his first time in the city; he’d been going into New York on his own ever since his days as a student at Newman and, later, Princeton. But this time Fitzgerald was arriving fresh out of the army, and he was set on conquering the publishing world, winning Zelda Sayre as his wife, and becoming a famous writer. New York City, back then, must have really been something. Fitzgerald, of course, put it best: looking back in his 1932 essay “My Lost City,” one of the greatest pieces of writing on the city—ever—he said, “New York had all the iridescence of the beginning of the world.”1

Just on the verge of the Roaring Twenties, New York was becoming the city we now know and that many of us love. It was the premier American city at a time when more and more Americans were migrating to metropolises. The 1920 census would show that, for the first time in the country’s history, more Americans lived in cities than in rural areas. Skyscrapers (“pincushions,” Henry James called them when he spotted some sprouting on his pilgrimage back to New York from England in 1904) were rising up in Lower Manhattan; by the end of the decade, many of the city’s most distinctive and beloved buildings—among them the Daily News Building, the Radiator Building, the Chrysler Building, and the Empire State Building—were finished or under construction.2 Up, the first word the toddler Fitzgerald uttered, is a word that he’d later use a whopping 202 times3 in Gatsby. Clearly, 1920s New York was destined to suit Fitzgerald’s high-flying aspirations.

But Gatsby, as we readers know, is relentlessly nostalgic, and so it’s fitting that so many of the elegant landmarks of the novel’s Manhattan date from the era of the city that immediately preceded the Jazz Age: the Plaza Hotel (1907), the Yale Club (1915), the old Pennsylvania Station (1910), the Queensboro Bridge (1909),4 and the white marble Tiffany Building at Thirty-Fifth Street and Fifth Avenue, where Nick runs into Tom Buchanan for the last time and reluctantly shakes his hand. Tom, Nick speculates, is going into the jewelry store “to buy a pearl necklace—or perhaps only a pair of cuff buttons,”5 potential purchases that remind us of Tom’s wedding present to Daisy and of Meyer Wolfshiem, to whom Tom is linked in brutishness. That Tiffany Building, designed by Stanford White, still stands near the old B. Altman department store, which has been turned into a complex now used by the City University of New York, the New York Public Library, and Oxford University Press. The Tiffany Building wasn’t so lucky in its new tenants: last time I checked, its ground floor was occupied by a Burger King. For better and worse, New York is all about change.

Literary scholar Ann Douglas talks about what was called the “airmindedness”6 of the twenties: a sense that nothing was too high or too far to be out of reach. The skyscraper boom was certainly a product of this aspirational attitude, as were the new medium of radio (conquering the airwaves!) and the advent of airplane travel. How fitting that New York State’s motto, prophetically adopted in the eighteenth century, is Excelsior, Latin for “Ever upward.” Think also about the poetic epigraph on the title page of Gatsby—or, rather, let me tell you about that epigraph, since, judging by the deer-in-the-headlights reaction that request usually elicits from my students, few readers do more than glance at that little poem on the novel’s title page:

Then wear the gold hat, if that will move her;

If you can bounce high, bounce for her too,

Till she cry “Lover, gold-hatted, high-bouncing lover,

I must have you!”

Like Lucky Lindy, high-bouncing Gatsby was a Jazz Age Icarus, brushing the clouds with his gold hat. It would be cool to credit Fitzgerald with an inspired discovery of a poem so precisely suited to both the striving spirit of the age and Gatsby’s core ambition; however, no such bard as Thomas Parke D’Invilliers ever existed—or, more precisely, he exists only as a character in the pages of Fitzgerald’s debut novel, This Side of Paradise. Fitzgerald must have been emulating one of his literary idols, T. S. Eliot, who’d concocted phony footnotes for his 1922 poem The Waste Land, when he thought of this literary gag.

There’s something fizzy and irreverent about that fake poem at the threshold of Gatsby. Nowadays, when The Great Gatsby has ascended to the Great Books pantheon, it helps to decalcify the novel by remembering that Fitzgerald was quite young when he wrote it (twenty-six to twenty-eight) and that he had a streak of silliness in his makeup that it took oceans of hard liquor and years of hard luck to kill. Fitzgerald’s letters into the early 1930s are packed with jokes and doodles and bogus quotes from the likes of Shakespeare’s mother. Not only was Fitzgerald himself young, but he was writing to an audience of other young people. The 1920s saw the emergence of America’s first youth culture, and Fitzgerald brought flappers and their “jelly-bean” boyfriends into the literary eye through This Side of Paradise, the defining novel of the Jazz Age. He didn’t need permission to begin Gatsby by quoting a more established author; that cheeky epigraph from D’Invilliers signals to those in the know that the story that follows and the voice that Fitzgerald tells it in is fresh and all his own.

The rowdy crew of writers who would become Fitzgerald’s compatriots in the 1920s—Edmund Wilson (whom he first met at Princeton), H. L. Mencken, George Jean Nathan, Dorothy Parker, Ring Lardner, and Ernest Hemingway, to name a few—would have gotten the joke. They were a boozy crowd who liked a good laugh, but all of them also were engaged in the very serious business of trying to modernize American literature, make it snappier and truer to the language of the city streets. We don’t think of The Great Gatsby as a slangy or tough-talkin’ novel; it is always, rightly, celebrated for its lyricism. But if you compare Gatsby to Fitzgerald’s debut novel, This Side of Paradise, you’ll see how the twenties loosened him up and how a wisecracking language percolated into Gatsby, making it more modern and urban. For all of its much-vaunted depiction of flaming youth engaged in risqué necking parties and wild drinking, This Side of Paradise reads like an Edwardian novel built on cinder blocks of purple prose. Even Fitzgerald’s brief descriptions in that novel are a mouthful: “The unwelcome November rain had perversely stolen the day’s last hour and pawned it with that ancient fence, the night.” Huh?

Gatsby, in contrast, is much less affected. Even though Ernest Hemingway is the guy always credited with stripping American sentences down to their essential parts and injecting streetwise lingo into his dialogue, there are more contractions and slang words in the opening pages of Gatsby than in the first chapter of Ernest Hemingway’s 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises. Nick displays a jaunty side to his reflections by using contractions like don’t and I’ve. Once he starts quoting remembered conversations with Daisy, Tom, and Jordan, his diction can verge on the ungrammatical: “It’ll show you how I’ve gotten to feel about—things,” says Daisy before she describes to Nick that famously cynical reaction upon learning that she had given birth to a girl.

Another mark of the striking modernity of Gatsby’s style is the fact that it shuns the kind of faux biblical pronouncements that abound in the work of Fitzgerald’s contemporaries. I’ll cite Hemingway again because he’s such a fan of oracular-sounding prose, from The Sun Also Rises, which takes its title from Ecclesiastes, all the way through to his last leaden novella, The Old Man and the Sea. William Faulkner and Thomas Wolfe also revel in the kind of Old Testament–, Milton-, and Shakespeare-speak that Gatsby sidesteps. (Just mentally flip through Fitzgerald’s titles in comparison to theirs: Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury and Absalom, Absalom!; Wolfe’s Of Time and the River and Look Homeward, Angel.) Sounding like a prophet, though, can pay off: Hemingway and Faulkner both won Pulitzers (Hemingway, one; Faulkner, two), as well as the ultimate laurel wreath: the Nobel Prize for Literature. The only medals Fitzgerald ever held were the ones he invented for Major Jay Gatsby.

But I’ve gotten ahead of myself. Here I am talking about the twenties and New York City and the advent of modernity and I’m even anticipating the subsequent cold-shouldering of Fitzgerald by the prize committees, and, meanwhile, it’s still 1919 and Scott hasn’t even stepped off his train yet. So, back to that opening scene: Fitzgerald arrived in New York City on February 22, 1919. His train would have pulled into the old Penn Station (the grand structure modeled on the Roman Baths of Caracalla that was built in 1911 and demolished in 1963), because the Atlantic Coast Railroad Line, which then traveled between New York and points south, ran on Pennsylvania Railroad tracks north of Washington, DC.7 When Fitzgerald stepped out onto the sidewalk in front of old Penn Station, New York City traffic did not screech to a halt; the skyscrapers failed to bow. Fitzgerald lasted in New York City fewer than five months. By the first week of July, he’d packed up his bags and hightailed it back to his parents’ house at 599 Summit Avenue in St. Paul.

These days, we call such adult children “boomerang kids”: twenty-somethings who can’t make it in the real world and so return to the shelter of their childhood bedrooms and life with mom and dad. When you think about how badly young Scott had screwed up his life by this point, you have some sympathy for his parents, whose reaction to their son’s failures was not recorded. To briefly review: Wealthy relatives step in to bankroll Fitzgerald’s prep school and Ivy League education; in return, Scott essentially flunks out of Princeton because of excessive drinking and high jinks with the drama clique. He enlists in the army, but his stateside military career, while keeping him out of harm’s way, is not the stuff of military legend. Then, to really make a mess of things, Fitzgerald gets engaged to a teenage Southern belle who isn’t even Catholic! All that was needed to make the situation a total train wreck was for that on-again, off-again fiancée to become pregnant—and, indeed, for some weeks after Scott paid a quick visit to Zelda in Montgomery while he was living in New York, Zelda feared that she was. When Fitzgerald showed up on his parents’ doorstep in midsummer of 1919 and announced that he was going to move into their top floor and work on his novel—a novel that had already been rejected twice by Scribner’s—they must have wondered whether their only son would be sponging off them for the rest of their lives. Fitzgerald’s parents let him in but refused to provide him with an allowance. That was a break for posterity. The image of F. Scott Fitzgerald at the age of twenty-two living at home and holding out his hand to Mom and Dad for spending money would have been too depressing.

What did Fitzgerald in on this first adult foray into New York is something my students and I talk about often in my New York literature course: the fear of being lost in the crowd. It’s a specifically urban variation on the primary American nightmare of drowning, going under. You can see that terror running throughout most New York City literature and film, but there’s an especially vivid depiction of it in a 1945 movie called The Clock, which stars Judy Garland and Robert Walker. The story takes place in New York City during World War II: Robert Walker is a soldier on forty-eight hours’ leave; Judy Garland is a secretary. They “meet cute” in Penn Station, the original majestic station that was the demobbed Lieutenant Fitzgerald’s point of entry into the city. In the very first scene, Walker, a hayseed from the heartland, exits his train and is immediately dazed by the hustle and bustle of Penn Station. He steps onto an escalator—his Gee, gosh! expression lets viewers know that this is the first escalator he’s ever ridden—and ascends to street level. That’s when things get freaky. Walker is overwhelmed by the noise and towering skyscrapers on Thirty-Fourth Street; the camera angles wobble, and Walker looks like he’s got the worst case of vertigo ever filmed pre-Hitchcock. Before he passes out, Walker manages to stumble back down into the safety of the station, where he meets his romantic destiny in the form of Judy Garland.

That recurring nightmare of being engulfed by the city in all its too-muchness runs through all types of New York stories. I think of Charles Dickens’s 1842 travelogue American Notes in which he describes the prolonged shudder of walking through New York streets bursting with “pigs, pedestrians, and prostitutes.” Jump ahead to the 1929 short story “Big Blonde” written by Fitzgerald’s friend Dorothy Parker or to Ann Petry’s 1946 novel about Harlem, The Street—both works of fiction bring to life the pressing claustrophobia of New York apartment houses and tenements. Even a valentine to the city like E. B. White’s classic 1949 essay Here Is New York talks about “the collision… of… millions of foreign-born people”8 in Manhattan. In modern novels like Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities and Paul Auster’s City of Glass, New York is a labyrinth; in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing it’s a jam-packed tinderbox. I could go on and on, but I’ll stop this disquieting overview with a line from E. L. Doctorow’s very best novel, The Book of Daniel, about the Rosenberg case. There’s a haunting sentence early in that novel that speaks to New York’s power to swallow people whole. Our narrator, Daniel, is recalling his childhood in the Bronx of the 1940s and says of his family: “I could never have appreciated how obscure we were.”9

In the New York City of 1919, Fitzgerald lost his footing and began to drown in obscurity. Upon his arrival, he had rashly wired Zelda: DARLING HEART AMBITION ENTHUSIASM AND CONFIDENCE I DECLARE EVERYTHING GLORIOUS THIS WORLD IS A GAME AND WHILE I FEEL SURE OF YOU[R] LOVE EVERYTHING IS POSSIBLE I AM IN THE LAND OF AMBITION AND SUCCESS.10 But Fitzgerald’s confidence soon fizzled. His master plan was to land a job writing for a newspaper by day and write short stories by night, but the office staff at the newspapers he called upon weren’t bowled over by his peculiar clips: scores he’d written for revues at Princeton. Fitzgerald settled for a grunt job with the Barron Collier Advertising Agency at ninety dollars a month, writing slogans primarily for displays in streetcars. His catchiest jingle was for an ad campaign touting a steam laundry in Muscatine, Iowa: “We Keep You Clean in Muscatine.”11 A few years later, Fitzgerald’s low-level familiarity with the flourishing world of advertising—another 1920s phenomenon—would inspire one of the most disturbing images in The Great Gatsby: the giant billboard in the valley of ashes that displays “the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg.”12 True writers salvage every experience, no matter how grim—that is, if they’re lucky enough to first salvage themselves.

With every passing month of his New York odyssey, Fitzgerald grew more anxious about his failure to set himself above the crowd. He’d moved into a rented room at 200 Claremont Avenue, near Columbia University. It sounds, from Fitzgerald’s description, like a typical postcollege dump: “one room in a high, horrible, apartment-house in the middle of nowhere.”13 The nearby intersection of 116th and Claremont Avenue is identified on a photograph in the New York City Municipal Archives as “the windiest intersection in New York City.”14 Certainly, the howling wind couldn’t have enhanced the charm of the isolated location. The apartment building that had threatened to entomb the twenty-two-year-old Fitzgerald was torn down in 1926, but if you look at period pictures of the neighborhood or at old zoning maps of New York City, you understand Fitzgerald’s depression. There’s nothing much going on way up there in 1919. Fitzgerald could have walked over to Riverside Park and Columbia University; he probably took the subway at 125th Street (the Interborough Rapid Transit line, or, as some called it, the Interborough Rattled Transit) to get to work. When he wasn’t drinking with old Princeton buddies, Fitzgerald sat in that apartment, night after night, writing short stories that were briskly rejected by the glossy magazines proliferating at the time.15 Generations of fledgling writers have taken heart from Fitzgerald’s oft-quoted recollection of having “one hundred and twenty-two rejection slips pinned in a frieze about my room.” He sold one story, “Babes in the Woods,” to the Smart Set, the New Yorker–type magazine founded by George Jean Nathan and H. L. Mencken, both of whom would later become friends of Scott and Zelda. One published story, though, wasn’t enough to cling to in the welter of New York City.

As his dream of becoming a writer stalled and the engagement with Zelda dimmed into less of a definite thing, Fitzgerald became less real to himself. Many years later, describing what he said were “the four most impressionable months of my life” in “My Lost City,” Fitzgerald refers to himself as “ghost-like,” both “hovering” and “haunted.” He also reaches for his essential nightmare image: the threat of drowning. “While my friends were launching decently into life I had muscled my inadequate bark into midstream.”16 One evening, while drinking martinis at the Princeton Club (which had temporarily merged with the Yale Club near Grand Central Terminal), Fitzgerald announced that he was going to jump out the window; the preppy humanitarians sitting in the lounge urged him on, pointing out that the windows were French and thus ideally suited for jumping through. After a quick visit to Montgomery to see Zelda, Fitzgerald reported for work at the Barron Collier Agency waving a revolver.17 Clearly, he was sinking fast. When Zelda ended the engagement in June, Scott went on a three-week bender. Then he cut his losses and escaped from New York.

In the decades I’ve been teaching my New York Stories course, I’ve come to recognize a pattern that I, as a lover of the city, don’t like very much. The pattern is this: Dreamers often come to bad ends in New York stories. The city attracts those who aspire to something greater, something different; oftentimes, it destroys them. Against-the-current types like Melville’s Bartleby (who “prefer[s] not to”); Wharton’s Lily Bart; Johnny Nolan, the starry-eyed dad in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn; the unnamed narrator of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man; and idealistic Holden Caulfield are just a few of the fictional characters who’ve been chewed up and spit out by New York. Fitzgerald wisely escaped before the rejection slips on the walls of that crummy apartment squeezed out all light and air. Gatsby wasn’t so smart. He’s drawn to New York as he’s drawn to Daisy, and both attractions are fatal.

New York City exerts a gravitational pull on every character in Gatsby. As Nick eloquently reminds us at the novel’s end, everybody in this jittery story has come to the city from somewhere else: “I see now that this has been a story of the West, after all—Tom and Gatsby, Daisy and Jordan and I, were all Westerners, and perhaps we possessed some deficiency in common which made us subtly un-adaptable to Eastern life.”18 We readers observe this pull at work most powerfully—and absurdly—in the climactic chapter 7 of the novel, whose opening is a mirror image of chapter 1. Again, the main characters—with the critical addition of Gatsby this time—are assembled in the Buchanans’ floaty living room. We’re told it’s the hottest day of the year, and Daisy, after luncheon, seems to be driven a little mad by the heat. She cries out: “What’ll we do with ourselves this afternoon… and the day after that, and the next thirty years?”19 The preposterous response to this existential question is for all of them to jump into the two available roadsters and drive into Manhattan. Who leaves an airy mansion on the Long Island Sound to drive into Manhattan on the hottest day of the year?

There’s clearly something that New York has that the characters think they need. The city, particularly during the Roaring Twenties, enjoyed the reputation of being tough and fast—in the sense of both speed and sexuality. No wonder Daisy feels perversely compelled to urge everyone on for that last fatal round trip to Manhattan; it’s appropriate that New York—the capital of Terrible Honesty, as critic Ann Douglas calls it (borrowing the line from hard-boiled-fiction writer Raymond Chandler)—should be the place where the truth will out about the limits of Daisy’s love for Gatsby. (Her awful admission to Gatsby, “Oh, you want too much!… I did love him once—but I loved you too,”20 takes place at the Plaza Hotel, no less, where the sounds of a wedding reception wickedly filter into the hotel suite where Gatsby and Tom and Daisy argue.) New York is about personal freedom and unsentimental sex; that’s why Tom and Myrtle’s love nest is located, not on Long Island or, heaven forbid, in the valley of ashes, but on West 158th Street. My students are often taken aback to realize that hooking up, looking hot, and acting blasé about sex aren’t fresh ideas; they’re at least as old as the Jazz Age. Only Gatsby holds himself apart from this Roaring Twenties hardness and hedonism centered in the city. His courtly love–style veneration of Daisy derives from a more chivalrous time, although a modern sexual freedom is also mixed into their relationship when you remember that they’re cheating on Tom and that they slept together when they first met five years earlier.

For our narrator, Nick, New York offers a more melancholy gift, what E. B. White called, in Here Is New York, “the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy.”21 Although he’s arrived in the city to buckle down and learn the bond business, Nick tells us that he was “restless” after the war and couldn’t stay put in the “middle-west.”22 Everyone in this novel is “restless”; it’s one of the ways Gatsby captures the atmosphere of post–World War I America. Nick also can’t settle down because he’s fleeing the pressure of a tacit engagement to a girl back home. No big romantic story there; he’s just not that into her. The oddest thing about this entanglement is that Nick himself doesn’t tell us about it; Daisy and Tom both mention that they’ve heard rumors about his engagement at the end of that opening dinner party. Taken together with Nick’s boast at the very end of chapter 3 that “I am one of the few honest people that I have ever known,”23 alert readers should start wondering whether Nick is completely leveling with them. But whatever Nick’s moral failings, he’s saved—for me, at least—by his love of New York. The Great Gatsby pays three radiant tributes to New York: the Queensboro Bridge passage; the ending of the novel, in which New York is conflated with America as “something commensurate to [man’s] capacity for wonder”24; and this lightly elegiac passage in which Nick sounds like a Jazz Age Walt Whitman:

“I began to like New York, the racy, adventurous feel of it at night and the satisfaction that the constant flicker of men and women and machines gives to the restless eye.… At the enchanted metropolitan twilight I felt a haunting loneliness sometimes, and felt it in others—poor young clerks who loitered in front of windows waiting till it was time for a solitary restaurant dinner—young clerks in the dusk, wasting the most poignant moments of night and life.”25

You can imagine Fitzgerald during the isolation of his months in the city in 1919 at one with those clerks and yet feeling desperately driven to set himself apart, to not waste his “most poignant moments.”

And what about our unfathomable friend Gatsby? Cities in general, and New York in particular, are where he makes his money, through the drugstores and soda fountains where his bootleg liquor is sold and in the shady bond deals he’s masterminding. Gatsby always seems more at home, though, in his car or hydroplane or mansion—gleaming places and machines that he controls. New York is too messy and unpredictable for Gatsby. Take that awkward business lunch with Meyer Wolfshiem in “a well-fanned Forty-second Street cellar.”26 The lunch culminates in an unplanned encounter with Tom Buchanan; earlier, Wolfshiem had gone off script by mistakenly raising the topic of a “business gonnegtion”27 with Nick, and Gatsby got flustered. You’d think that Gatsby is fit strictly for a gated community in suburbia except for one thing: the novel conflates Gatsby with New York City. They’re both over-the-top phenomena, mysterious and beautiful and fabricated. When Nick and Gatsby drive over the Queensboro Bridge in one of the most indelible scenes from the novel, Nick tells us:

“Anything can happen now that we’ve slid over this bridge,” I thought; “anything at all.…”

Even Gatsby could happen, without any particular wonder.28

Gatsby, the visionary con man, is as much an improbability as New York City, itself both a wonder and a con.

That mention of the lunch with Wolfshiem and that drive over the Queensboro Bridge compels me to consider one of the elephants-in-the-classroom topics that frequently come up these days: Where does the novel stand on issues of immigration and race? The answer is that Gatsby doesn’t stand in one place about anything; rather, this is a novel that jumps and ducks and shimmies. I think one big reason why Fitzgerald set The Great Gatsby in the mixing bowl of New York is that he wanted to weigh in, albeit ambiguously, on some core American issues, and the city was the center for debates in the 1920s about foreign influences, eugenics, and racial “pollution.” Post–World War I New York was reeling from the colossal wave of immigrants that had begun pouring into the city in the 1880s. Between the late 1880s and 1919, more than seventeen million immigrants to the United States entered through New York City,29 and many of them went no further than New York. Unlike earlier immigrant groups from Northern Europe, the second wave was composed of non–English speakers, many of whom sported darker complexions: Russian and Polish Jews, Greeks, Southern Italians, Poles, Hungarians, Romanians, Bohemians, and others from Southern and Eastern Europe. Then, as now, lots of native-born Americans were nervous about what these new immigrants would do to the country. And that was in addition to the African Americans who were arriving in the city as part of the Great Migration from the South. The Great Gatsby is more than a little nervous about all these newcomers. Gatsby hears the “foreign clamor” on the streets of New York, and it’s not exactly music to the novel’s ears.

It’s strange for me to think that in 1919, as Fitzgerald was making the rounds of those newspaper offices and dragging his heels homeward at night to that upper Upper West Side apartment, he might have passed my own pregnant grandmother Helen (or Helena) Dobosz. She was a Polish immigrant, one of that second wave, who arrived in New York alone at seventeen and worked almost all her life as a cleaning lady. Her second child, my mother, was born in 1919 in a tenement on Avenue C, about seven weeks after Fitzgerald quit New York and hurried back home to St. Paul. To hear most of my students talk about Gatsby, you’d think that all of New York in the Jazz Age was drinking champagne and dancing the Charleston. Gatsby, however, knows better; for better or worse, it notices people like my grandmother.

That Queensboro Bridge passage anxiously surveys the folks who wouldn’t have been invited as guests into Gatsby’s mansion: immigrants like my grandmother as well as African Americans, even those “New Negroes” with money in their pockets and plenty of attitude. Gatsby’s car glides onto one lane of the Queensboro Bridge roadway, and it’s left in the dust by a funeral cortege composed of people “with the tragic eyes and short upper lips of south-eastern Europe” and a “limousine… driven by a white chauffeur, in which sat three modish Negroes, two bucks and a girl.”30 Nick laughs at the black passengers’ look of “haughty rivalry” as their car speeds by Gatsby’s roadster, but the novel itself isn’t laughing. If you know your New York geography, you catch the ominous tone of this fast-moving scene. That the new immigrants are linked with a funeral is bad enough, but consider that those snooty African Americans pass our two white guys (Nick and Gatsby) as all the cars are specifically said to be driving over Blackwell’s Island. These days, Blackwell’s Island is called Roosevelt Island and it’s the site of upper-middle-class apartment developments, but in Fitzgerald’s day it was a sinister place—home to a prison, a charity hospital, a smallpox hospital, and the Women’s Lunatic Asylum of New York City. (Intrepid stunt journalist Nellie Bly went undercover, posing as a mentally disturbed woman, to expose brutal conditions in there in 1887; Fitzgerald identified Bly as his model for Ella Kaye, the journalist who cheats the young Jay Gatsby out of his inheritance from his mentor, Dan Cody.31) The fact that such a grim island lurks beneath the glorious bridge and that the faster cars carrying immigrants and black folk are allied with death and disease betrays, to put it mildly, a worry about where an increasingly diverse America was headed. In Fitzgerald’s 1926 story “The Swimmers,” its hero, Henry Marston, surveys the onslaught of Americans in Paris and thinks: “All that was best in the history of man must succumb at last to these invasions, as the old American culture had finally exhausted its power to absorb the bilge of Europe.”32 I suspect that in his less attractive moments, Fitzgerald regarded the non-English-speaking immigrants swirling around him as “the bilge of Europe.”

Readers have to work a little to unpack the Blackwell’s Island symbolism, but no heavy lifting is required with the figure of Meyer Wolfshiem. As scores of Fitzgerald scholars have pointed out, the portrait of Meyer Wolfshiem was inspired by the real-life figure of Arnold Rothstein, the New York Jewish racketeer known as “the Brain” and “the Big Bankroll” who was rumored to have fixed the 1919 World Series. Fitzgerald recalled in a 1937 letter that he’d met Rothstein, although the particulars of that meeting have been lost to history.33 (Gatsby himself owes something to Edward M. Fuller, one of Fitzgerald’s Great Neck neighbors, who had been convicted, along with his brokerage firm partner William F. McGee, of stealing their clients’ money. Another model for Gatsby lurks in the career of Max Gerlach, a bootlegger, mechanic, and car dealer who had a dealership on Northern Boulevard in Flushing, Queens, near the valley of ashes. Gerlach and Fitzgerald knew each other and there’s a newspaper clipping in Princeton’s F. Scott Fitzgerald Papers on which Gerlach has scribbled the Gatsby-like greeting: How are you and the family, Old Sport? Before she died, Zelda shored up the Gatsby-Gerlach association by suggesting that Gatsby was based on “a neighbor named Von Guerlach or something who was said to be General Pershing’s nephew and was in trouble over bootlegging.”34 Gatsby, ultimately, can’t be confined to a historical source. Unlike Wolfshiem, he’s the stuff that dreams are made of, an amalgam of many people, most of all F. Scott Fitzgerald himself. To round out the early 1920s criminal sources for Gatsby’s story, Sarah Churchwell, in her recent book Careless People, makes a case for the sensational Hall-Mills murders as an inspiration for the homicidal finale of Gatsby. (In September of 1914, the bullet-riddled bodies of an Episcopal priest named Edward Wheeler Hall and his janitor’s-wife mistress, Eleanor Mills, were discovered near New Brunswick, New Jersey. Their deaths were much grislier than the trio of deaths in Gatsby: In addition to being shot, Mills had had her throat slashed and her tongue cut out. The murders were never solved.)

Back to the disturbing figure of Wolfshiem. With Rothstein as his base, Fitzgerald proceeded to embellish. Indeed, it’s as though Fitzgerald were tinkering with a Mr. Potato Head, Anti-Semitic Edition, as he constructed the figure of Wolfshiem. The first piece is the nose, which Fitzgerald describes as “flat” and “expressive,” in which “two fine growths of hair… luxuriated in either nostril.”35 Next comes the heavy accent, which marks Wolfshiem as a nativist’s nightmare, an unassimilated outsider no doubt risen up from the “Yiddish Quarter” of the Lower East Side. The pièce de résistance is, as I’ve already noted, Wolfshiem’s occupation. Like Shakespeare’s Shylock and Edith Wharton’s villain Simon Rosedale in The House of Mirth, Wolfshiem is, among other things, a moneylender whose distinctive cuff buttons (as they’re called in the novel) silently communicate the warning Let the borrower beware!

Molars may not be as gruesome as a pound of flesh, but still, they’re an offensive fashion accessory. Wolfshiem seems to have become a problem for Fitzgerald as the years passed. In her lovely memoir of her twenty months working as Fitzgerald’s last secretary, Frances Kroll Ring remembers that when Fitzgerald was writing The Love of the Last Tycoon, he wanted to avoid making the villain (Brady) Jewish:

He said he had, on occasion, been rebuked for his portrait of… Meyer Wolfshiem in Gatsby. Scott was stung by the criticism which he considered unfair.… He was a gangster who happened to be Jewish. But sensitivities were running high in this period (the late 1930s) and Scott did not want to have any link with prejudice or anti-Semitism.36

Ring, herself a Jew, also recalls that Fitzgerald was fascinated by a Passover story she told him about how her parents kept a live carp swimming in their bathtub at home until her father clobbered it with a hammer and her mother made it into gefilte fish. “Scott shook his head in disbelief at this fish story. Then a cunning light came into his eyes as he commented that he would never have brought the fish to such a savage end. He would simply have filled the tub with gin and let the fish drink itself into oblivion.”37

Anti-Semitic? Check. Racist? Check. Nativist? Check. (Let’s set aside sexist and homophobic for the moment.) If you want to subject The Great Gatsby to a political purity test, it flunks. Gatsby is at once timeless and time-bound, a social novel of the 1920s as much as it is a free-floating Great American Novel. But view the novel in its entirety rather than in isolated passages, and its politics get more complicated. The novel clearly relishes more than it fears the modernity and mixing of New York City. Once again, think of Nick’s New York tribute that starts: “I began to like New York, the racy, adventurous feel of it at night.” The mythic landscape of Gatsby is laid out like a compressed Candy Land game board, in which the valley of ashes rubs shoulders with the Eggs; Myrtle and Tom’s love nest nestles a couple of quick spaces away from the Plaza. That kind of compressed geography is possible only in a city. The very air of the novel is redolent of diversity: the jazz tunes that waft through Gatsby are products of the city and of what critics have called “artistic miscegenation” between black and white musicians and composers. (Ironically, Fitzgerald himself was not that much of a jazz aficionado; all the evidence—letters and lists of recordings—point to his strong love for classical music.) And only in New York could Gatsby’s parties attract such a zany collection of nouveau riche immigrants as well as theater and movie stars. Many of the early silent film companies had studios in New York and on Long Island, among them Famous Players–Lasky, which built a studio in Astoria, Queens, in 1920 and made the first (silent) film of The Great Gatsby in 1926. The company later became Paramount, and it made two more film versions of Gatsby, in 1949 and 1974. Panning the static 1974 version, New York Times reviewer Vincent Canby invoked Gatsby’s death-by-drowning anxieties when he described the film as “lifeless as a body that’s been too long at the bottom of a swimming pool.”38

The strongest argument, however, against taking Gatsby to task over its political incorrectness—against giving free rein to what the late British historian E. P. Thompson so eloquently termed “the enormous condescension of posterity”—comes from the most unlikely of sources: Tom Buchanan.

Tom Buchanan. My heart leaps up at the prospect of thinking about Tom! A college football player whose glory days are behind him, Tom is all meat. Nick’s opening description of Tom makes him sound like a bison: “You could see a great pack of muscle shifting when his shoulder moved under his thin coat.”39 Whenever he’s indoors, Tom always seems too big for his surroundings. He’s always breaking things: Daisy’s little finger; Myrtle’s nose; ultimately, Gatsby’s dream.

Tom was loosely based on a real person: polo player and war hero Tommy Hitchcock Jr., who was a fellow St. Paul Academy alum and a genuine hero of World War I. (He had left St. Paul’s early to join the Lafayette Flying Corps in France. When Hitchcock was shot down and captured by the Germans, he escaped by jumping out of a train. He walked over one hundred miles by night to reach the safety of Switzerland.) Hitchcock was Fitzgerald’s lifelong ideal of a man of action, so to turn him into Tom, Fitzgerald had to scoop his spirit out, retaining the heft of Hitchcock’s frame but filling it with straw.

Tom possesses Hitchcock’s confidence (evident in period photos), but he hasn’t done anything to earn it—except be born rich. In late November of 1924, Max Perkins wrote Fitzgerald a long and detailed response to the draft of Gatsby that he’d received a month earlier. (Upon reading the novel through the first time, Perkins had immediately responded with a quick note that began with what were surely some of the best words F. Scott Fitzgerald had ever heard: “Dear Scott, I think the novel is a wonder.”40) In his longer letter, Perkins put on his editor’s cap and told Fitzgerald that “Gatsby is somewhat vague.”41 But Perkins prefaced his criticism of Gatsby with this comment about Tom: “I would know Tom Buchanan if I met him on the street and would avoid him.” Fitzgerald clearly agreed. He wrote Perkins back from the damp hotel in Rome where he and Zelda and Scottie had holed up for a few weeks that Christmas season:

“My first instinct after your letter was to let [Gatsby] go + have Tom Buchanan dominate the book (I suppose he’s the best character I’ve ever done—I think he and the brother in ‘Salt’ and Hurstwood in ‘Sister Carrie’ are the three best characters in American fiction in the last twenty years, perhaps and perhaps not) but Gatsby sticks in my heart.”42

Like Max Perkins, we readers also know Tom. We’ve sat next to him on a plane or train. He’s our retired neighbor down the street, our office mate. He’s that fellow in our carpool or someone’s date seated at our table during a wedding reception. Or, as in Nick’s case, he’s our cousin’s husband. Tom is That Guy Who’s Read a Book. Maybe it’s Blink by Malcolm Gladwell or Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother by Amy Chua or The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan. Or maybe it’s Mein Kampf. In Tom’s case, the book is The Rise of the Colored Empires “by this man Goddard.”43 It’s given Tom what so many people seem to want: the one theory that explains the universe. And now, whether we want to hear it or not, Tom is (like his real-life counterparts) hell-bent on explaining that theory to us.

The Rise of the Colored Empires riffs on the title of an actual bestseller, The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy, by Lothrop Stoddard, which Fitzgerald’s own publisher, Scribner’s, brought out in 1920. Scribner’s, pre-Fitzgerald, was known as a conservative publishing house, and that conservatism extended to its political leanings; Max Perkins—and the authors he brought into Scribner’s—did a lot to shake things up. Fitzgerald made up the name Goddard out of a combination of Stoddard and Madison Grant, another eugenicist who wrote a popular book called The Passing of the Great Race in 1916. As is often the case with such boorish readers, Tom has only roughly grasped the argument of the book. (Grant talked about the disappearance of Nordics, and Stoddard, a “scientific racist,” called for a eugenic separation of the races, but he was also a critic of European colonialism.) Grant’s and Stoddard’s—or Goddard’s—argument has been brining in Tom’s brain for a while, and in that first scene at the Buchanans’ mansion, Nick gives Tom an opening by speaking the trigger word civilized. Tom erupts:

“Civilization’s going to pieces,” broke out Tom violently. “I’ve gotten to be a terrible pessimist about things. Have you read ‘The Rise of the Colored Empires’ by this man Goddard?”

“Why, no,” I answered, rather surprised by his tone.

“Well, it’s a fine book, and everybody ought to read it. The idea is if we don’t look out the white race will be—will be utterly submerged. It’s all scientific stuff; it’s been proved.”44

Note that in his summation of Goddard’s idea, Tom fumbles for a verb and comes up with the word submerged. There’s that drowning image again. Somebody is going to wind up being submerged in this book, but it’s neither Tom nor Nick; neither Daisy nor Jordan. No, the only white guy who doesn’t make it out of the water alive is Gatsby. Who knows? Given his hard-to-place original surname, Gatz, and given the fact that he’s described as “tanned,” Gatsby might not even be pure Aryan stock. If so, it’s appropriate, in Tom’s view, that he’s the guy who goes under while the others survive.

But hold on: Tom is a boob! He spouts racist nonsense, and the novel rolls its eyes at him for doing so. As Tom rants on, Daisy begins mugging like a Jazz Age Lucille Ball, winking and whispering asides to Nick. Jordan tries (unsuccessfully) to interrupt Tom’s monologue, which she’s no doubt sat through many a time before. Nick tells us, “There was something pathetic in his concentration, as if his complacency, more acute than of old, was not enough to him any more.”45 How gently understanding that sentence is. There are cultural changes in the air that Tom’s thick antennae pick up on, but he doesn’t know how to respond except by digging in his riding-boot heels and shoring up his white-male supremacy by quoting fragments from probably the only book he’s read since graduating Yale—with a gentleman’s C, no doubt.

Because Tom’s tirade is played for laughs in the very first chapter of The Great Gatsby, it reassures us from the outset that the novel is inclusive, even progressive, in its politics. Then we run smack into Wolfshiem and watch in dismay as those speeding carloads of immigrants and African Americans roar past Gatsby and Nick on the Queensboro Bridge. What to think, what to think? Certainly the novel carefully notices race and ethnicity; Gatsby, undeniably, is worried about an America on the move, and it checks out just where these “others” are headed and how fast they’re going. Fitzgerald himself was reading Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West in 1924 as he was intently working on Gatsby, and that two-volume threnody couldn’t have helped his outlook on the future of Western civilization. But, but, but… that antic automobile race—which dramatizes Goddard’s and Tom’s very fears—concludes on a note of anticipation, not dread. Nick thinks: “Anything can happen now that we’ve slid over this bridge… anything at all.…”46 Maybe the most accurate thing to say about the politics of Fitzgerald’s novel is that, as a product of the early to mid-1920s, Gatsby doesn’t know yet what’s going to happen to America. The novel keeps its mind open, even if it’s a conflicted one. Only Tom and his “simple mind”47 have all the answers. One of the many breathtaking achievements of The Great Gatsby is that it thoroughly engages its time without being a one-dimensional political novel.

New York City was the epicenter of all these American questions about immigration and race; democracy was literally being tested on its streets. Like Paris, New York was also a mecca for writers, artists, musicians, and architects who itched to “make things new.” Fitzgerald, holed up writing in his parents’ rented house at 599 Summit Avenue, didn’t plan to stay away very long. Fortunately, the third time round turned out to be the charm for This Side of Paradise. At a September editorial board meeting at Scribner’s, Max Perkins bulldozed the manuscript through the unanimous nay votes. (He threatened to quit if the other board members didn’t change their vetoes.) Fitzgerald was over the moon. When he received Perkins’s acceptance, he ran out of his parents’ house and giddily waved the letter at passing cars. A couple of days afterward, Fitzgerald wrote to a Minnesota friend named Alida Bigelow who was away at college. He heads the letter “1st Epistle of St. Scott to the Smithsonian” and then proceeds to natter nonsense rhymes until, finally, he tells her the news: “Scribner has accepted my book. Ain’t I Smart!”48 You could see how Fitzgerald, even in his happy prime, could be a high-maintenance friend.

In preparation for his debut, Fitzgerald moved back to New York City, staying first at the Murray Hill Hotel and then at the Allerton. On the actual publication day, March 26, 1920, he briefly moved to New Jersey to his spiritual home, the Cottage Club at Princeton. This Side of Paradise sold out its first printing of three thousand copies in only three days. The novel became a phenomenon because it was lively and risqué (couples necked, petted, and drank) and announced a new spirit of the age. On the first of April, Fitzgerald moved into the Biltmore, which, at a minimum of two dollars and fifty cents a night (European plan), rivaled the Plaza as one of the priciest hotels in the city.49 The reason for the move was his other big day: his impending marriage to Zelda Sayre. Fitzgerald’s confidence, along with his wallet newly flush with fees from his short stories (which had also broken through to publication), had convinced Zelda that Scott was her man, and their engagement had been resumed over the winter of 1919–1920. On April 3, he and Zelda were married in the vestry of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Zelda was nineteen years old; Scott was twenty-three. Curiously, neither set of parents came to the wedding, but Zelda’s three older sisters, two of whom lived in New York, attended. The “Affidavit for License to Marry,” which an efficient archivist unearthed for me at New York City’s Municipal Archives, lists Scott’s occupation as “writer” and Zelda’s as “——.” Both their signatures are firm and flashy, although Scott made a bit of a mess, blotting his last name. Probably he was nervous. Following the short ceremony (not even a lunch afterward, according to Zelda’s aggrieved sister Rosalind), Scott and Zelda walked out of the vestry and became the toasts of the town.

When guests complained about the loud parties at the Fitzgeralds’ honeymoon suite at the Biltmore, the couple moved a block south to the Commodore (also two dollars and fifty cents a night, European plan), where, pulling one of the many pranks that would make them celebrities, they spun for an hour in the revolving door, a relatively new device. Life was indeed a whirl of parties, drinking, high jinks (those infamous dips in New York City’s fountains), theater outings, dancing, and more drinking. Their behavior brings to mind college kids on a prolonged spring break (they were, after all, as young as college kids, although better-looking than most). Though the conventional opinion about Zelda is that her beauty eluded the camera’s eye, I think that oft-circulated 1923 photo of the Fitzgeralds on the cover of Hearst’s International magazine is stunning. With her marcelled hair, Zelda looks like a Jazz Age golden sphinx. Zelda joked that she was wearing her “Elizabeth Arden face” for that photo, and clearly, New York had worked its sophisticated magic on this Alabama beauty. When Zelda arrived in New York for their wedding, Scott had panicked about her Southern belle costumes. Ever anxious, like Gatsby, about self-presentation, Scott prevailed upon a female friend, Marie Hersey, to help teach Zelda how to dress in a more cosmopolitan manner. Zelda hated the Jean Patou suit she bought on this first foray into New York shopping, and Scott-bashing biographers point to this incident as support for their reading of him as an overbearing control freak, but the makeover scene is a standard episode in coming–to–New York stories (especially female ones) as disparate as Mary Cantwell’s Manhattan, When I Was Young and Patti Smith’s Just Kids. New York has always held out the promise of fresh starts, of reinvention. By the time Zelda learned to powder on her Elizabeth Arden face, she had become the top girl of the twenties.

Nothing puts a damper on a good time like a deadline, however, and Fitzgerald had a lot of them. There were short stories to write for the high-paying glossies and a new novel to think about. (Scribner’s established the pattern of publishing collections of Fitzgerald’s short stories in between his novels; Fitzgerald would write approximately 160 stories during his lifetime.) Because New York was too distracting, he and Zelda moved in the summer of 1920 to an eighteenth-century farmhouse in Westport, Connecticut, near Long Island Sound. This was the first time Fitzgerald had the opportunity to take a prolonged look out over those fateful waters. Ever restless, Scott and Zelda moved back to the city in the fall, to an apartment at 38 West Fifty-Ninth Street. A trip to Europe followed. (In the Fitzgerald Papers at Princeton, there’s a 1921 letter from Archbishop Dowling of St. Paul to a Monsignor O’Hearn requesting an audience with the pope for Fitzgerald. “Mr. Scott Fitzgerald… desires greatly to see our Holy Father when he visits Rome this summer.” Maybe Pope Benedict XV got a whiff of Fitzgerald’s published material, because the requested audience never came about.) The following October was marked by Scottie’s birth, in St. Paul, Minnesota. In 1922, Fitzgerald’s second novel, The Beautiful and Damned (the one that’s always acknowledged as “the New York novel”), was serialized in Metropolitan magazine and then published in book form. Sales of this story about the marriage of drifting Manhattan socialites were good, topping fifty thousand copies.

At White Bear Lake in Minnesota, where the Fitzgeralds were living at the Yacht Club in the summer of 1922, Scott did some preliminary work on what would be his third novel. At this point, that third novel was envisioned as taking place in the nineteenth-century Midwest and having some kind of Catholic theme. In mid-July, he wrote a brief letter to Maxwell Perkins (still addressing him as “Mr. Perkins”) about various business matters, but in the last sentence of that letter he gives Perkins—and readers—the very first intimations that Gatsby is materializing: “I want to write something new—something extraordinary and beautiful and simple + intricately patterned.” Then, as though he’s a bit nervous about what he’s just confessed, Fitzgerald reins in this confession of ambition by signing the letter primly, “As Usual, F. Scott Fitzgerald.”50

The only fragment left of this ghost Gatsby is “Absolution,” a short story about a young boy and the Catholic priest on the edge of a nervous breakdown who’s hearing his confession. It was published 1924 in the American Mercury, a magazine started that year by H. L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan. Along with “Absolution,” three other stories in what critics call the Gatsby cluster were published in magazines in the mid-1920s “Winter Dreams” (Metropolitan, 1922), “The Sensible Thing” (Liberty, 1924), and “The Rich Boy” (Redbook, 1926). All four of these stories fixate on the act of reaching for someone or something that is just out of one’s grasp. In “Absolution,” the fraying priest, Father Schwartz, makes a short speech that sounds as though Fitzgerald intended it to be a warning to a young Gatsby figure. Wandering around his study, Father Schwartz approaches Rudolph Miller, the frightened eleven-year-old boy who’s trying to make a confession, and asks him:

“Did you ever see an amusement park?”

“No, Father.”

“Well, go and see an amusement park.” The priest waved his hand vaguely. “It’s a thing like a fair, only much more glittering. Go to one at night and stand a little way off from it in a dark place—under dark trees. You’ll see a big wheel made of lights turning in the air, and a long slide shooting boats down into the water.…”

Father Schwartz frowned as he suddenly thought of something.

“But don’t get up close,” he warned Rudolph, “because if you do you’ll only feel the heat and the sweat and the life.”

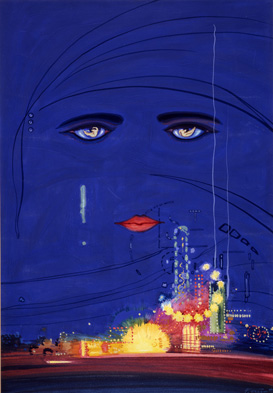

When Spanish-born artist Francis Cugat created the dust jacket for The Great Gatsby, he ended up enshrining that image, first invoked in “Absolution,” of distant amusement-park lights. Surely this is the most famous dust jacket in the relatively short history of dust jackets. They may eventually go the way of record-album covers, but fortunately for posterity, Cugat’s brief career as a dust-jacket designer coincided with the giddy beginning of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. A portrait painter and a set designer, Cugat was also the older brother of Xavier, the bandleader. Cugat was paid one hundred dollars for the Gatsby dust jacket, the only one he ever did. (Don C. Skemer tells me of a joke in the antiquarian book trade about the Gatsby first edition being a $750 book with a $150,000 dust jacket.) Maybe Cugat gave up on the dust-jacket racket because it involved too much work for too little pay. As sketches that came to light in the 1990s show us, Cugat labored over other ideas for the Gatsby cover. These earlier sketches are clearly inspired by the valley of ashes. At first, they seem to be in a more realistic mode, depicting a few tumbledown houses under clouds. Then you notice that the clouds have eyes and mouths.51 At the time Cugat was invited to design the cover, he would have heard, presumably from Max Perkins, that the novel—still in progress—was called Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires.

Like so much else about The Great Gatsby, what happened next is mysterious and contingent. At some point in August 1924, Fitzgerald, still in France, saw Cugat’s dust-jacket design and went gaga for it. “For Christ’s sake don’t give anyone that jacket you’re saving for me,” he wrote to Perkins. “I’ve written it into the book.”52 But if Perkins mailed him one of Cugat’s sketches, what image did Fitzgerald see and write into Gatsby? If it was the valley-of-ashes sketch with the surreal cloud creatures, then Cugat may have inspired Fitzgerald to conjure up the eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg. If Fitzgerald saw the later image of a sad femme fatale face floating over a nighttime cityscape ablaze with amusement-park lights, it seems the likely source of Nick’s allusion to Daisy as a “girl whose disembodied face floated among dark cornices and blinding signs.”53 Like so many other questions about The Great Gatsby, this one about the long-distance “collaboration” between artist and writer is impossible to answer unless some lost correspondence between Perkins and Fitzgerald comes to light. I do know this for certain: Francis Cugat, who may have only heard about Gatsby from Max Perkins, was one of the sharpest early readers of the novel. Fitzgerald said of the assessments of Gatsby, “Of all the reviews, even the most enthusiastic, not one has the slightest idea what the book was about.”54 In Cugat, however, Fitzgerald had the extraordinary luck to be matched with an illustrator—an artist—who got that the book was about reaching out, aspiring, for a mirage.

The original book jacket for The Great Gatsby: “Celestial Eyes” by Francis Cugat. (PRINCETON UNIVERSITY LIBRARY)

Like everyone who’s read and reread The Great Gatsby in the standard Scribner’s paperback edition, I’ve looked at Cugat’s cover so often that it’s one of those overly familiar images, like the American flag or the Eiffel Tower, that you no longer really see. But my vision was restored by a close encounter with the real thing. In late summer of 2013, an art curator at the Firestone Library at Princeton wheeled the framed poster-size gouache painting that Cugat called Celestial Eyes into the rare-book room. The real painting is even more abstract than paperback reproductions suggest: there are lots of yellow flares and letters of the alphabet—s’s and p’s and f’s—floating around the deep blue night sky; many minor Ferris wheels swirl in the foreground and many shadowy tenement buildings loom in the background. But above all, what hit me was that Cugat nailed the sense of longing that infuses Gatsby. Those brooding eyes with the nudes swimming in their irises will forever hover in the distance. That beautiful woman can’t be grasped; she’d dissolve through your fingers if you tried. These are not the heavenly eyes of God; they’re the celestial eyes of a pagan deity who floats above a secular “bright lights, big city” world.

After about twenty minutes of close study of Cugat’s painting, I tried to turn my attention to the archival box of Fitzgerald’s letters that was on the library table. My eyes kept drifting back to the painting. I finally had to ask for Celestial Eyes to be removed from the room. It’s impossible to ignore. (Hemingway seems to be the lone dissenter in his opinion of Cugat’s dust jacket; in A Moveable Feast, he describes it as “garish” and says, “It looked like the book jacket for a book of bad science fiction.”55)

Like The Great Gatsby itself, Cugat’s painting was almost literally tossed into the dustbin of history… or, more precisely, into Scribner’s trash can. Charles Scribner III later donated the painting to Princeton. (Scribner is a member of the class of 1973.) He was able to do so because his cousin George Schieffelin fished Celestial Eyes out of a container of publishing “dead matter” in the Scribner’s building and took it home. The painting was passed on to family members until it came safely to rest, with the Scribner’s archive, at Princeton.56

There’s no way Cugat could have known that Zelda Fitzgerald, herself an embodiment of the “eternal feminine” of his painting, seems to have been an enthusiast of carnivals and amusement parks. Novelist John Dos Passos wrote about his adventure of riding in a Ferris wheel with an exhilarated Zelda. Dos Passos’s recollection is intriguing, not only because it’s so harsh but because of the practical reason why he and Zelda were thrown together in the first place. It was September of 1922, and the Fitzgeralds had left baby Scottie with family back in St. Paul to hunt for a house to rent outside New York City. (Preparing to move back to the city from St. Paul, Fitzgerald wrote to Max Perkins: “I never knew how I yearned for New York.”57) On the day Dos Passos joined the Fitzgeralds, they all drove out to Great Neck, Long Island, where they called on a drunken Ring Lardner. On the drive back, Zelda insisted that they stop at an amusement park. Scott stayed in the car, sulking and drinking, while Zelda and Dos Passos went on the ride. Dos Passos later wrote:

The gulf that opened between Zelda and me, sitting up on that rickety Ferris wheel, was something I couldn’t explain. It was only looking back at it years later that it occurred to me that, even the first day we knew each other, I had come up against that basic fissure in her mental processes that was to have such tragic consequences. Though she was so very lovely I had come upon something that frightened and repelled me, even physically.58

Talk about the dangers of getting up too close. Anyone who’s read “Absolution” will hear Father Schwartz’s warning echoing between the lines of Dos Passos’s sad little story.

Dos Passos doesn’t seem to have been along for the ride the day the Fitzgeralds found their rental house, 6 Gateway Drive in Great Neck, which Zelda described as a “nifty little Babbit-home.”59 Like so many of the homes and apartments associated with the Fitzgeralds, it looks like a nondescript dwelling in period photos. Built in 1918, the small house with a red-tiled roof and cream-colored walls still stands, and over the decades, it’s been enlarged and beautifully upgraded. The Fitzgeralds rented it for three hundred a month60; its sale price today is in the millions, but none of the online realty sites that routinely list property information mention the fact that F. Scott Fitzgerald began sketching out The Great Gatsby there, in the summer of 1923, in a “large bare room” over the garage outfitted with “pencil, paper and oil stove.”61

As biographer Matthew J. Bruccoli details, “that slender riotous island”62 that the Fitzgeralds found themselves living on provided plenty of raw material for the book. In 1938, Fitzgerald recalled the mostly New York–and Long Island–based sources for Gatsby’s chapters in a list he scribbled on the endpaper of his copy of André Malraux’s newly published book about the Spanish Civil War, Man’s Hope:

- Glamour of Rumsies + Hitchcoks

- Ash Heaps. Memory of 25th. Gt Neck

- Goddards. Dwanns Swopes.

- A. Vegetable Days in N. Y.

B. Memory of Ginevras Wedding - The meeting all an invention. Mary

- Bob Kerr’s story. The 2nd. Party.

- The Day in New York

- The murder (inv.)

- Funeral an invention63

Determined to lay off the booze, Fitzgerald fueled himself with pots of coffee and cranked out a lot of stories in the late winter of 1923 and early spring of 1924 in order to gain uninterrupted time to write his next novel. Most of those stories are forgettable, the exception being “The Sensible Thing,” one of the Gatsby-cluster tales that deal with Fitzgerald’s signature theme: the attempt to recapture a lost vision of happiness. “The Sensible Thing” draws much from Fitzgerald’s miserable months in New York City in 1919. In it, failed architect turned insurance salesman George O’ Kelly lives on 137th Street in a one-room sublet. George is in love with a fickle Tennessee belle named Jonquil Cary, and the story hinges on the question of her faithfulness to George. While he was furiously generating (lesser) short stories for cash, Fitzgerald, as always, was reading. Great Neck is where, probably upon Lardner’s recommendation, Fitzgerald plunged into Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov and Dickens’s Bleak House (the latter became his favorite Dickens novel).64 Other works of literature that to some degree affected the alchemical composition of Gatsby were Joseph Conrad’s The Nigger of the Narcissus (to which critics credit the invention of Nick Carraway as a partially involved narrator) and the works of Willa Cather, particularly, as Fitzgerald respectfully told her in a letter written in late March or early April of 1925, the novels My Antonia and A Lost Lady and the short stories “Paul’s Case” and “Scandal.” That letter was resurrected in the New Yorker in the wake of the Baz Luhrmann–generated Gatsby frenzy of May 2013; in it, Fitzgerald confesses to a case of “apparent plagiarism” in describing Daisy’s allure in terms similar to those that Cather used for the love object in A Lost Lady. Cather, whom Fitzgerald idolized, was gracious about the apparent plagiarism (Fitzgerald told her he had written his Daisy passage before he read A Lost Lady). I’d nominate Cather’s odd story “Paul’s Case,” published in McClure’s Magazine in 1905, as an even more potent if more diffuse influence on The Great Gatsby. The tale of a sensitive boy from Pittsburgh who craves beauty and the finer things, “Paul’s Case” follows the brief ascent (through crime) of the main character, who succeeds in winning himself a few precious days of luxury at the Waldorf hotel in Manhattan before he dies. Cather anticipates the yearning and the tragic arc of another poor boy, James Gatz from North Dakota, reaching out for his own version of the green light.

Fitzgerald was working hard and trying to cut back on his drinking because he felt scared. All artists are insecure; their reputations are at the mercy of their last books, or plays, or paintings, or films. Can I pull it off again? After This Side of Paradise set the standard so high, Fitzgerald was privately tormented by that question in the early 1920s. By the early 1930s, his torment was dramatized in public. Fitzgerald was struggling with Tender Is the Night and had already abandoned a couple of novels, including one whose subject was matricide. (One novel in progress that did see the light of publication—and shouldn’t have—was Fitzgerald’s medieval romance Philippe, Count of Darkness. Amateur historian Fitzgerald aimed to explore the beginnings of the feudal system through the exploits of a swashbuckling hero modeled on Hemingway. Redbook began serializing this disaster in October 1934. The headnote for the second installment reads like an Onion spoof: “The brilliant thought quality and style of the creator of The Great Gatsby are very much in evidence in this majestic story of 819 A.D.”65 Philippe, Count of Darkness bit the dust after installment three, although a fourth installment was posthumously printed in November 1941, no doubt because Fitzgerald’s recent death had made the creaky tale a curiosity.)

In 1923, Fitzgerald’s self-doubts were already congealing. His big effort of the past year, a play called The Vegetable, debuted and expired in Atlantic City in November of 1923. (Zelda reported to a friend that “in brief, the show flopped as flat as one of Aunt Jemimas famous pancakes.”66) Under the sway of his friend H. L. Mencken, Fitzgerald had ventured into what was for him the foreign territory of political satire. The Vegetable tells the story of an ordinary man who wants to be president but can’t even make it as a postman. Its subject is outsize American ambition. The Vegetable played this subject for laughs; The Great Gatsby would treat the same subject with reverence.

So from the late winter of 1923 through the early spring of 1924, Fitzgerald sat at his desk in that chill room over the garage on 6 Gateway Drive, challenging himself to make something magical. One of The Great Gatsby’s most repeated words is unutterable; alone in his writing studio, Fitzgerald may have wondered if he could find the words for his own unutterable visions. Writing to Perkins (by now “Dear Max”) in a crucial letter dated April 10, 1924—exactly a year to the day before The Great Gatsby would be published—Fitzgerald apologizes for the slow progress he’s making on his new novel, especially because he’s thrown out much of what he wrote the previous summer. He says he hopes to have the novel done by June, but then backtracks: “And even [if] it takes me 10 times that long I cannot let it go out unless it has the very best I’m capable of in it or even as I feel sometimes, much better than I’m capable of.”67 Fitzgerald, as was his way, then lambastes himself for all his bad habits—among them “drinking,” “raising hell generally,” “laziness,” “Referring everything to Zelda,” and “word consciousness—self doubt.” Toward the end of the letter, he swings back to self-confidence, then returns to self-loathing, then back, finally, to nervous self-affirmation:

I feel I have an enormous power in me now, more than I’ve ever had in a way but it works so fitfully and with so many bogeys because I’ve talked so much and not lived enough within myself to delelop [sic] the necessary self reliance.… In my new novel I’m thrown directly on purely creative work—not trashy imaginings as in my stories but the sustained imagination of a sincere and yet radiant world. So I tread slowly and carefully + at times in considerable distress. This book will be a consciously artistic achievement + must depend on that as the 1st books did not.…

Please believe me when I say that now I’m doing the best I can.68

I don’t see how anyone who reads Fitzgerald’s letters and the biographies (even the ones written by Zelda partisans) can possibly come away without feeling two things: first, some contempt for Hemingway (the man, not his work), and, second, a deep respect for Maxwell Perkins (the man and his work). As A. Scott Berg showed in his magnificent 1978 biography Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, Perkins was a literary visionary, graced with extraordinary reserves of patience and generosity toward even the neediest and most erratic writers under his wing. Surely, there must have been times when Fitzgerald—who used Perkins as a therapist and a banker as well as an editor—just plain wore him out.

If the writing room where Fitzgerald chopped and reconceived his earliest version of The Great Gatsby was spare, the views of nearby Manhasset Bay were to die for. On summer nights, Scott and Ring Lardner could sit outside the Lardner house on 325 East Shore Road and look across the dark water or over at the blazing parties under way at the neighboring mansion of New York World publisher Herbert Bayard Swope, who happened to be friends with gangster Arnold Rothstein. Here’s how Ring Lardner Jr., around eight years old at the time, later mapped out the geography and the atmosphere of that charmed period:

“There was a porch on the side of our house facing the Swopes’ and Ring and Scott sat there many a weekend afternoon drinking ale or whiskey and watching what Ring described as an almost continuous house-party next door.”

The location of the Swopes’ house was just right for the view of Daisy’s pier across the bay.69

Besides Lardner, other neighbors were New York show-business types like Ed Wynn, Eddie Cantor, and Groucho Marx. (Jews were allowed to rent and buy homes in Great Neck, one of the only Gold Coast towns to have such progressive real estate policies.) Fitzgerald rubbed shoulders at parties out in Great Neck with theatrical and artistic types like Gloria Swanson, Marc Connelly, Dorothy Parker, and Rube Goldberg; after all, as we readers know from Gatsby, Great Neck was an easy commute to the bright lights of the city. On a good evening, a roadster could cruise straight down Route 25 (Northern Boulevard), through Corona (the valley of ashes), Astoria, and Long Island City, over the Queensboro Bridge, and onto Broadway in about an hour. Fitzgerald was a notoriously slow and bad driver. New York City traffic pamphlets of the time put the speed limit on Northern Boulevard at forty miles an hour, so it probably would have taken him longer to make the commute.70

My family made that commute—in reverse—most weekends when I was growing up in the 1960s. On those weekend rides “out to Long Island,” we never veered over to Port Washington or Great Neck proper. When we rode out on Northern Boulevard, we passed the shops that lined Manhasset’s Gold Coast, but we rarely stopped. We were in search of cheaper entertainments: a dose of history (Teddy Roosevelt’s Sagamore Hill) or dinner at Howard Johnson’s or, in the summer, a swim at Oak Beach. We sometimes did go off the beaten path on “literary” field trips (Washington Irving’s home, Sunnyside, in the Hudson Valley was a favorite), but though my dad was a great reader, I don’t remember him ever mentioning Gatsby or any of Fitzgerald’s other books. Born in 1920, my father was too young for Fitzgerald’s “first flowering”; by the time the revival gathered force, my dad’s love of serious literature was mostly nostalgic and he was reaching for World War II adventure stories and thrillers. So, though I’d passed within miles of it on those childhood weekend rides, I’d actually never laid eyes on Fitzgerald’s “courtesy bay.” That’s how it came to be that in 2013, my husband, my fourteen-year-old daughter, and I took a Father’s Day weekend road trip up from Washington, DC, out to Long Island for what turned out to be an amiable floating tourist trap billed as the Great Gatsby Boat Tour.