“Ahoy!” calls out a young woman (already buzzed?) as she and the rest of what seems to be a wedding party clamber aboard the small vessel—think the Minnow of Gilligan’s Island fame—that’s going to carry us out on the waters between East Egg and West Egg and into Long Island Sound. Rich, Molly, and I have already staked out our spots on the bench that runs around the inside of the boat and are eyeing our fellow passengers filling the spaces. There’s a woman beautifully dressed in full 1920s regalia: a tan-and-black flapper dress, cloche hat, and long ivory-bead necklace. She’s reluctantly followed by Olive, a gray and white standard poodle who’s being tugged aboard by her human. Meanwhile, the wedding party is getting louder; they’re mugging for cell-phone selfies and shouting witticisms like “Hello, old sport!” Wine bottles are being unscrewed as the boat’s engines rev up. A young dude on the starboard side is busy dissing both Fitzgerald and Hemingway to the woman sitting next to him. “What’s the takeaway?” he asks her, in reference to The Sun Also Rises. As the dock recedes to the point of No Exit, I’m not thinking about either Fitzgerald or Hemingway; I’m thinking about Sartre and the apt remark from that play: “Hell is other people.”

Our guide is a cheery middle-aged woman who tells us that she lives in the area and got the idea for this “floating” walking tour of Great Gatsby sites when she lost her job in the publishing industry. She also tells us she took Baz Luhrmann and his wife, costume designer Catherine Martin, out on Manhasset Bay to tour the Eggs in 2008 in preparation for Luhrmann’s Gatsby film. Despite these credentials, she’s relying heavily on notecards to give the bare bones of Fitzgerald’s biography. One thing our guide mentions endears her to me: she says she didn’t get Gatsby the first time she read it, but now, every time she rereads it, she wishes it were longer.

Whatever. Hardly anyone on the boat is listening. It’s a beautiful bright summer’s day out on the water and almost everyone else is leaning back, drinking whatever alcohol they’ve brought with them, and enjoying the view of wretched excess that the waterside mansions of Great Neck (West Egg) and Manhasset Neck (East Egg) continue to provide. We gaze at a pretty white colonial mansion that we’re told Groucho once rented and that’s now owned by Bill O’Reilly. (Molly, an ardent Rachel Maddow fan, snorts loudly.) Our attention is directed to Sid Caesar’s relatively modest rambler and then we gawk at what was, long ago, publisher Jock Whitney’s timbered lodge, now updated and preposterously enlarged: this thing could accommodate every reader who bought a copy of Gatsby in 1925. Our guide informs us that she’s heard rumors that actor Adam Sandler bought the place for his parents. I smile, thinking of the wild rumors that swirled around Gatsby. The rich and their doings out on this spit of land are still generating gossip.

As the boat heads out into Long Island Sound, we pass a boarded-up house on the very tip of West Egg—a spot that enjoys simultaneous views of the Manhattan skyline and an East Egg castle across the bay, which the first mate tells me belongs to the guy who owns the Arizona Beverage Company. (An iced-tea salesman in East Egg; Tom Buchanan would be disgusted.) But it’s the boarded-up house that should give anyone who’s read Gatsby a moment’s pause. Our guide tells us that a murder was committed in the house, and for legal reasons, it can’t be sold. A murder house in what looks to me to be the location of Gatsby’s fictional house? C’mon. It’s only the fact that this boat tour is so blasé about making any connections whatsoever to Gatsby that leads me to believe in this eerie correspondence.

After spending the first fifteen minutes of the tour fumbling with notecards and hazy facts (“Fitzgerald was born in… I want to say, Minnesota?”), our guide commands those few of us still tuning in to “enjoy!” and totters off to join the flapper and her escort, who’ve just popped open a bottle of champagne. Rich, Molly, and I exchange shrugs; for this we got up at dawn and drove seven hours? Across the deck, Olive has put her head between her paws, and one of the wedding party appears to be seasick. The facial expressions of the seasick woman and Olive the poodle mirror each other.

I try to breathe deep and accept my powerlessness as recommended by the online daily meditation program I sporadically log on to. At least I’ve finally seen the Eggs. As a spatially challenged person, I’m always trying to figure out where West and East Eggs are in relation to Manhattan, and I still sometimes stumble in classroom lectures. Overall, though, this excursion reaffirms my armchair-traveler inclinations. (I’ve been mentally drawing lines through my bucket list of literary sites—Haworth Parsonage, Jane Austen’s Bath—as we sail around the Eggs.) Fitzgerald’s language creates the fantasy of Gatsby’s Long Island; even if I could take a time machine back, I’d probably be disappointed. Though I’d still like a summer’s night swigging gin gimlets with Ring and Scott on Ring Lardner’s porch.

Earlier in the tour, when we sailed by the narrow inlet that separates West Egg and East Egg, the guide pointed out a business park dominated by a boxy utilitarian building and told us that was the spot where Lardner’s house once stood. Swope’s mansion is also gone, the place that hosted the likes of George Gershwin, Robert Moses, the Vanderbilts, Irving Berlin, and the Marx Brothers. (Bill O’Reilly and the rumored presence of Adam Sandler’s parents are indisputably a comedown.) As our little boat pulls into the dock, I decide to ask the guide if it’s possible to see the outside of 6 Gateway Drive. I know the place still stands because I’ve seen real estate photos: it’s a Mediterranean-style stuccoed house that, given its crucial role in American literary history, deserves a marker. (According to Fitzgerald scholar Ruth Prigozy—who tried to get such a marker placed—there’s a rule that allows only one historic-house marker per author.71) Given that my expectations have plummeted during the past ninety minutes, I’m surprised by the guide’s practical knowledge of the house and the surrounding property. She tells me that a Rite Aid drugstore now abuts the property. If we approach 6 Gateway Drive through the Rite Aid parking lot, we can take some pictures of the house “before the police arrive.” I look at Rich and Molly. Then, as one, we thank the guide, step onshore, and walk off toward an ice cream parlor we spotted earlier. Some places are best to dream of, not visit.

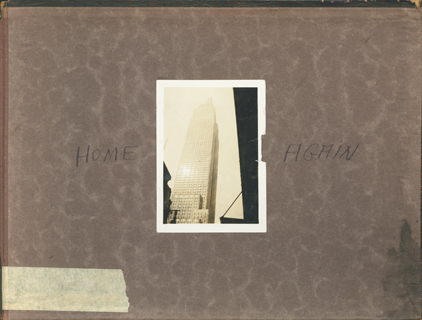

The great New Yorker writer A. J. Liebling said of New York City that its “geography was [its] destiny,” meaning that from its early New Amsterdam days, the city, situated at the top of a grand natural harbor where two rivers met, could not avoid its happy fate as a commercial center. For The Great Gatsby as well, geography was destiny: Great Neck provided Fitzgerald with a perfect landscape in which to make Gatsby’s transcendent longing materialize. Before the Fitzgeralds resolved, once more, to economize—this time by relocating to Europe in early May of 1924 (going by way of a ship that was “dry,” Bruccoli points out, to underscore Fitzgerald’s dedication to his writing regimen)—Scott soaked up New York City and environs. Neither he nor Zelda ever lived in New York again: they bounced between Europe and America a few times over the next seven years, in 1928 renting a grand house called Ellerslie in Delaware for six months and then returning to France. By September 1931, when the three Fitzgeralds came back to the United States for good, Zelda had suffered her first breakdown and institutionalizations. On the very last page of one of their family photo albums, there’s a crooked black-and-white snapshot of the Empire State Building, which had officially opened three months earlier. On each side of the photo, Scott or Zelda or Scottie has printed in block capital letters: HOME AGAIN.

A photograph of the Empire State Building from Fitzgerald’s personal album, inscribed with the words “Home Again.” (MATTHEW J. & ARLYN BRUCCOLI COLLECTION OF F. SCOTT FITZGERALD, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA LIBRARIES)

New York City was Scott and Zelda’s best home. Their sojourn there was bound up with the first happy years of their marriage, the Jazz Age, and Scott’s early success. The Great Gatsby is sprinkled with fleeting insider references to locales and haunts (the “poolroom on 43rd” where Wolfshiem and Gatsby first met; those cool “big movie houses on 50th”; “the old Metropole”) that attest to the fact that, during his time in New York, Fitzgerald—like Poe and Whitman; like Alfred Kazin and Joan Didion—became “a walker in the city.” Gatsby is so much a product of New York that on the day it was published, Fitzgerald was prompted by a tone-deaf comment made by one of his uncles to add this postscript to a nervous letter to Max Perkins:

I had, or rather saw, a letter from my uncle who had seen a preliminary announcement of the book. He said:

“it sounded as if it were very much like his others.”

This is only a vague impression, of course, but I wondered if we could think of some way to advertise [The Great Gatsby] so that people who are perhaps weary of assertive jazz and society novels might not dismiss it as “just another book like his others.” I confess that today the problem baffles me—all I can think of is to say in general to avoid such phrases as “a picture of New York life” or “modern society”—though as that is exactly what the book is its [sic] hard to avoid them.72