3

Rhapsody in Noir

I love that, as that clueless letter from his uncle shows, even F. Scott Fitzgerald had to suffer family members who didn’t get what he was doing. I also love that Fitzgerald acknowledges to Perkins that Gatsby is a modern New York story. But I don’t think Fitzgerald was just talking about geography when he writes that Gatsby is “a picture of New York life.” He’s saying something about the mood and the form of the novel—qualities that the New York City of the 1920s specifically gave him. He’s pointing to something contemporary about Gatsby’s shadowy atmosphere of criminals, bootleggers, and violence. I also think, to use a word Fitzgerald himself used in reference to his novel, that he’s referring to Gatsby’s intricate structure: its compressed sense of time and hyperawareness of deadlines; its voice-over style of narration and its deliberately tangled story lines. Fitzgerald wouldn’t have applied the term noir to these aforementioned elements in Gatsby; noir didn’t emerge as a term for a certain kind of dark film until after World War II. Fitzgerald, however, did toss around the distinctively Jazz Age term hard-boiled. I’m convinced that, in referring to The Great Gatsby as a modern New York novel, Fitzgerald is also saying that there’s something hard-boiled about it, an aspect to his poetic masterpiece that derives from the very same urban American sources that inspired the gals-guts-and-guns school of fiction that evolved into the pulp magazines of the early to mid-1920s.

The Great Gatsby as a near relation of the hard-boiled novel? Jay Gatsby as an “associate” of such tough guys as Three Gun Kerry and Race Williams? Those readers who segregate literary categories the way Tom Buchanan segregates races will find this suggestion preposterous, even offensive. But as critic Alfred Kazin pointed out in his landmark collection of critical essays on Fitzgerald published in 1951, Fitzgerald “constantly crossed and recrossed the border line between highbrow and popular literature.”1 There’s plenty of incriminating evidence of significant “gonnegtions” between the hard-boiled school and The Great Gatsby. Think, first of all, about our hero’s name: Jay Gatsby. A gat is twenties slang for a gun. Certainly, Gatsby must have been packing, at least in the early years of his rise in Meyer Wolfshiem’s employ. Chew on the coincidence that the premier pulp magazine of the 1920s and 1930s was The Black Mask, founded by Fitzgerald’s good friends H. L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan in 1920 as a popular venture that would support their “classier” literary publication, the Smart Set. (Mencken and Nathan also founded two soft-core “naughty” magazines to generate income: Saucy Stories and Parisienne.) Also take into account that Fitzgerald was on very cozy terms with the word hard-boiled. In 1934, in a preface to the Modern Library edition of The Great Gatsby, he called himself “a hard-boiled professional.” And, most suggestively, the word hard-boiled appears in the very first chapter of Gatsby. Take another look at Nick Carraway’s introduction in chapter 1. As Nick is presenting his family tree for our inspection, he mentions a great-uncle who founded his family’s line in America and made a fortune: “I never saw this great-uncle but I’m supposed to look like him—with special reference to the rather hard-boiled painting that hangs in Father’s office.”2

Nick’s use of the word hard-boiled is fairly new; hard-boiled was a term coined by soldiers during World War I to refer to particularly tough drill sergeants. Fitzgerald may well have heard the word—or used it himself—during his sojourns in all those army training camps. Before World War I, the term variously meant “practical,” “stingy,” and “tough to beat,” as in a hard-boiled egg. Nick’s comment that his uncle’s portrait is hard-boiled could invoke all those meanings. Hard-boiled in the specific sense of “practical” and “tough” is an adjective that also applies to Nick himself. Though we tend to think of Nick as a Gatsby double, he’s much less sentimental, especially in his treatment of women. He breaks up, long distance, with that fiancée back home, and casually dumps the office girl he has a fling with during his New York summer. He’s especially efficient in his treatment of Jordan Baker: “You threw me over on the telephone,” Jordan says. “I don’t give a damn about you now but it was a new experience for me and I felt a little dizzy for a while.”3 At the close of the novel, our Nick is even tough enough to shake Tom Buchanan’s hand—the hand of the man who fingered Gatsby to his murderer, George Wilson. As critics and scholars unanimously affirm, one of the extraordinary advances that Fitzgerald made in Gatsby was his decision to have the main character’s tale told from the outside by an observant narrator. That inside-outside perspective preserves the central air of mystery that surrounds Gatsby (we’re never completely clear on what he’s done to make his money), but it also provides us readers with two radically different sensibilities: Gatsby’s idealistic reading of romantic love and American possibility versus Nick’s relatively more practical, more hard-boiled grounding.

Some of the contemporary reviewers of The Great Gatsby zeroed in on its hard-boiled elements, which by now are mostly buried under fossilized layers of Great Books–type reverential criticism. Fanny Butcher, reviewing the novel for the Chicago Daily Tribune on April 18, 1925, was generally enthusiastic, although she granted that “it is bizarre. It is melodramatic. It is, at moments, dime novelish.”4 Reviewer Baird Leonard, writing in the April 30, 1925, issue of Life, summarized Gatsby as though it were a short story written by Damon Runyon:

It is the story of a super-four-flusher whose parties at his Long Island place were attended by thousands and whose untimely coffin was followed by two.… When you get through with the story, you feel as if you’d been some place where you had a good time, but now entertain grave doubts as to the quality of the synthetic gin.5

The notice for The Great Gatsby that Scribner’s placed in the April 4 issue of Publishers’ Weekly lures potential readers with promises of both hard-boiled intrigue and romance. The copy reads: “The story of Jay Gatsby, who came so mysteriously to West Egg, of his sumptuous entertainments and of his love for Daisy Buchanan.”6

All that for just two dollars! The Gatsby announcement, by the way, is wedged between notices for one of Putnam’s spring titles, The Women of the Caesars (which was translated by Fitzgerald’s Princeton mentor Christian Gauss), and Abraham Flexner’s Medical Education: A Comparative Study. In that same issue of Publishers’ Weekly, splashy advertisements sing the praises of The Constant Nymph, a romance by Margaret Kennedy, and Edna Ferber’s So Big, which won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1925.

The titles of two of the first European translations of The Great Gatsby—one, in Norwegian, The Yellow Car; the other, in Swedish, A Man Without Scruples—invite readers to expect a suspense tale. In his own lifetime, Fitzgerald sparked much less interest from foreign readers and reviewers than either Hemingway or Faulkner. Fitzgerald, culturally speaking, didn’t seem to translate well; judging by the reviews he did get, Fitzgerald was regarded as “too American” in an overeager and superficial way. Other marks against Fitzgerald, according to European critics, were that his writing lacked intellectual content and, during the 1930s, a leftist political point of view. Typical of this kind of Old World patronizing attitude toward Fitzgerald was V. S. Pritchett’s sniffy retrospective comment in 1951 that Fitzgerald “was not a thinker but was simply impressionable.”7

The British firm William Collins, Sons published This Side of Paradise, The Beautiful and Damned, and Fitzgerald’s short-story collections. William Collins himself, however, turned down The Great Gatsby, claiming that “the British public would not make head nor tail of it.”8 His prediction was borne out a year later when Chatto and Windus published the novel and it made “no stir at all.”9 Gatsby received only six reviews from the British press, as opposed to sixteen for Tales of the Jazz Age.10 Gatsby’s first appearance on the Continent was in France in 1926: Victor Llona did the translation (universally regarded as dreadful) for Kra’s Collection Européenne. Fitzgerald himself paid the translator’s fee, and sales were poor. Only half of the first printing of eight thousand copies were sold. Curiously, Norway and Sweden—these days, literary centers of the hard-boiled mystery novel—were the only other foreign countries to translate The Great Gatsby when it was first written. The titles of those two translations are the ones that suggest a fascination with the hard-boiled elements in the novel.

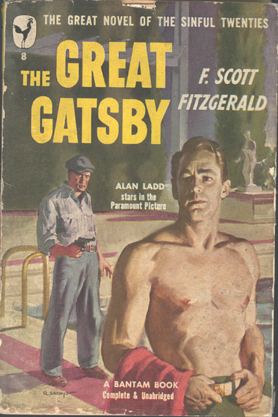

I’m jumping ahead a couple of decades, but now seems like the right moment to bring up my favorite film version of The Great Gatsby made in 1949, directed by Elliott Nugent, and starring Betty Field as Daisy and Alan Ladd as Gatsby. This version of Gatsby reads the novel as an underworld crime saga and the movie itself is noir in terms of its sensibility if not, strictly speaking, its camera techniques. So as not to rile the film scholars, I’d call it noir-ish. These days—thanks to the renewed interest in Gatsby films stirred up by Baz Luhrmann—you can download the 1949 film from the Internet. By happy necessity, in the summer of 2012, I had the thrill of watching it the old-fashioned way, on a reel-to-reel projector, in a dim basement screening room of the Library of Congress.

In the film’s very first shot of Alan Ladd as Gatsby, he’s leaning out of a speeding black roadster and machine-gunning down some rivals in the bootlegging business. (This scene immediately follows the bizarre “prologue” to the movie where a now-married Nick and Jordan stand over Gatsby’s grave and spout a 1940s-era regretful tribute to the 1920s: A redeemed Jordan, played by the dark-haired character actress Ruth Hussey, begins the sermon, and Nick soon joins in: “It seems like another world, Flaming youth… The speakeasy… Prohibition… rum runners… the gang wars.”) Ladd is pretty good as Gatsby: he’s handsome and vacant enough, which seem to me to be two qualities essential to Gatsby the cipher. By 1949, Ladd was a huge star, known for doing elegant turns on the tough-guy role in films such as This Gun for Hire, The Glass Key, and The Blue Dahlia (stories by mystery masters Graham Greene, Dashiell Hammett, and Raymond Chandler, respectively). In one of those big, exotic party scenes that every Gatsby director clearly loves to film, we’re treated to Indians in feathered headdresses, women on horseback trotting through Gatsby’s mansion, and other guests strolling around in saris and turbans. During that scene, Ladd’s Gatsby slugs a guest who fingers him as Gatz. There are lots of smart touches in this 1949 Gatsby—including a very young and very hysterical Shelley Winters as Myrtle (a role she was born to play), a Wolfshiem wittily renamed Lupus, an Owl Eyes who quotes Keats’s femme fatale poem “La Belle Dame Sans Merci,” and a steaming valley-of-ashes set that looks like it was designed by Samuel Beckett.

Two elements, however, deserve special attention in this prolonged glance at the noir-ish Gatsby. First, this Gatsby film obsesses about Dan Cody, a character who’s largely ignored in the other extant film versions and in most discussions—scholarly or popular—of the novel. In the Ladd film, the camera lingers on the water with a young Gatsby aboard Dan Cody’s yacht. Cody, played by Henry Hull, looks and sounds like Mephistopheles. He’s forever spouting every-man-for-himself business aphorisms: “If a smart man sees anybody ahead of him, he just moves in anyway”; “You got money, you just take.” Capitalism here is thus equated with selfishness and thuggish behavior, especially striking given that Gatsby is often misread as an endorsement of the philosophy that greed is good. Cody is creepy, but even more intriguing is that all the dames in this film—at least in their first appearances—are femmes fatales. When Cody dies and Ella Kaye gains control of his fortune, she threatens Ladd’s Gatsby: “Don’t forget, I’m at the wheel now.”

At the end of the film, right before he’s shot in his Greco-Roman-style pool, Ladd’s Gatsby, supine in a terrific tight-fitting bathing suit, makes a hard-boiled redemption speech to Nick, played competently enough by Macdonald Carey. Ladd’s Gatsby says: “I’m through four flushing, trying to be something I’m not, a gentleman.… I was a sucker.… I’m going to pay up, Nick.” The death scene is the other striking element in this film because it dwells obsessively on Gatsby’s final throes in the pool. (This film overall is a very damp version of Gatsby; for example, in the rainy reunion scene between Gatsby and Daisy at Nick’s house, Jordan jokes, “Anyone got a rowboat handy?”) Ladd’s Gatsby is shot, swims, tries to pull himself up, and then is shot two more times before he goes under. His death by drowning is drawn out and intense. At the eleventh hour, though, this version of Gatsby steps back from the black pit of noir despair and scurries to save its sinners: Daisy insists that Tom, played by beefy Barry Sullivan, warn Gatsby of Wilson’s approach; Tom stolidly complies, but Ladd’s Gatsby ignores the insistent ringing of the telephone. Jordan, as indicated already in the prologue to the story, renounces her cheatin’ ways and thus proves herself worthy of Nick’s love.

The Bantam paperback cover of Gatsby, featuring Alan Ladd. (MATTHEW J. & ARLYN BRUCCOLI COLLECTION OF F. SCOTT FITZGERALD, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA LIBRARIES)

Because this hard-boiled B-movie version of Gatsby wasn’t available on the Internet until recently, I chose a clip from a different noir film to play for the audience gathered to hear my take on The Great Gatsby on the chill evening of October 23, 2008. I was in Perry, Iowa, that night as an emissary of the Big Read project. The Big Read was launched by the National Endowment for the Arts in response to an alarming 2004 NEA report called “Reading at Risk” that showed that less than half of American adults had ever read a work of literature in their leisure time. To make matters even more depressing, literature was defined pretty inclusively: romance novels, serial-killer suspense stories, and dirty limericks were eligible. The NEA decided to combat this threat to an informed democracy by sponsoring “one town, one book” events in libraries and civic centers all over America. Interested communities selected from a list of fiction titles put together by the NEA (among them Fahrenheit 451, The Maltese Falcon, To Kill a Mockingbird, and The Great Gatsby) and received critical materials for reading groups and lectures by “experts” like me.

Tonight, it’s Perry’s turn. The local citizens have been reading and rereading Gatsby, learning 1920s dances at a soiree at the Golf and Country Club, watching the 1974 film, and buying bright green T-shirts printed with a caricature of a smiling Fitzgerald in a tiny roadster. I’ve arrived in Perry to give the keynote address that will cap off the whole effort.

Perry, which I will explore over two days, is a Midwestern treasure: a tiny railroad town about thirty miles outside of Des Moines that boasts a Carnegie Library Museum and the Hotel Pattee, opened in 1913. Both buildings have been restored to their original splendor by a wealthy local benefactor. The hotel, where I’m staying in a needlework-theme room, houses a wooden bowling alley in its basement and a very nice bar. After my talk, I’ll enjoy a couple of rounds of bracing gin and tonics with the locals, including Perry’s mayor, a sharp middle-aged woman who’s refreshingly outspoken in her political views. At that point in that particular October, everybody is more caught up in the looming presidential election than in Gatsby, but that’s okay. I like this town whose motto is Make Yourself at Home! I can see the attractions of living here (the effect of those two gin and tonics?), except there’s no work. As I’ll learn the following morning when I visit the local high school, the nearby Tyson chicken plant is one of the chief employers in the area.

I’m self-conscious about my role as Great Books booster. I’ll continue to be self-conscious about this role over the next few years as I serve as an itinerant preacher for the greatness of Gatsby at other Big Read events in places like Bowling Green, Kentucky, and Peoria, Illinois. The sponsoring librarians are almost always dynamic, smart women who tirelessly promote the pleasure of reading books, but they’re beating on against the powerful current of all manner of electronic gadgetry (although I’m certainly not opposed to people reading e-books). The new public library in Peoria, where I’ll speak a couple of years later, is mostly filled with computers, Blu-Rays, and DVDs. (The same is true of the new public library in my own Northwest Washington, DC, neighborhood.) I assume most of my audience that night in Perry will be white; indeed, the whiteness of the crowd any time I talk about Gatsby outside of a school setting underscores the fundamental problem with talking about any novel as one of “our” Great American Novels, one that “we” should all read. In the immortal (if apocryphal) words of Tonto, “Who you calling ‘we,’ white man?” The Big Read program has tried to acknowledge the racial and ethnic realities of America by putting works like Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God and Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club on the master list, but the crowds for Gatsby, at least, still skew as white as those billowing curtains in the Buchanans’ living room. The crowd in Perry that night is also overwhelmingly female, and middle-aged to elderly, which means that the folks assembled in the meeting room on the second floor of the Town/Craft Center look a lot like the crowds who gather for most literary and NPR events. Since almost everyone will have already read Gatsby in high school, I can deviate from the Gatsby-as-vitamin-for-the-brain pep talk that I fear I’m expected to deliver as cultural emissary from the capital. Indeed, the printed program for my talk in Perry confirms my suspicions: it stresses a message of literary uplift. Printed on the back cover in bold letters are bullet points courtesy of the NEA: Good readers make good citizens and Good readers generally have more financially rewarding jobs. (I like the cautious use of that adverb generally.)

True enough. Yet I also want to point out that all great art is wayward and dangerous: it messes with our imaginations and plants outsize fantasies in our brains. Jimmy Gatz, after all, might have been better off had he not read Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography, the inspiration for that youthful self-improvement list that his father posthumously finds in Jimmy’s paperback copy of Hopalong Cassidy. I want to recognize that disruptive, rogue quality in Gatsby, and so I’ve given my talk the mildly contrarian title of “The Great Gatsby: Just How American Is This Great American Novel?”

Maybe the edgy title worked because the town hall is packed that fall evening. Or maybe I just don’t have much competition in Perry that night. After I’m introduced, I cue the librarian/technical assistant. On the movie screen behind me, Billy Wilder’s classic 1950 noir Sunset Boulevard begins to roll.

If you’ve seen it, you’ll remember the opening: To the accompaniment of sirens and Franz Waxman’s jittery score, police motorcycles and sedans packed with tabloid photographers careen down a palm-lined road. Sunset Boulevard is stenciled in white letters on a curbside. The cops and newshounds screech up the driveway of an ornate mansion, “the home of an old-time star.” Some of the men run to the front door; others out to the back, where there’s a pool. The body of a young man is floating in the pool. The camera angle changes and it’s as though viewers are standing on the bottom of the pool, looking up at the victim’s open-eyed face. All this time there’s been a voice-over: a man has been calmly talking to us, explaining what we’re seeing. As we viewers gaze up at the wet corpse, the voice-over quips: “Poor dope, he always wanted a pool. Only the price turned out to be a little high.” The next scene takes us back a few months, into a crummy apartment in LA where a writer is banging away on a typewriter. Turns out the writer is William Holden, the actor we’ve just seen floating facedown in the pool. We realize, as the narrator switches to I, that we’ve been listening all this time to a dead man.

The lights come on in the Town/Craft Center and I make a feeble joke about the mistake of opening my talk with such a mesmerizing film clip, because now everybody just wants to go home and watch Sunset Boulevard. Nervous laughter because everybody knows it’s true. Even I want to ditch the lecture and watch Sunset Boulevard. But I forge ahead because it’s obvious, from the quick conversations I’ve been having with the Perry-ites before my talk, that almost everybody who has reread Gatsby still wants to talk about it as a beautiful and sad love story. (“Do you think Daisy ever loved Gatsby?” adults at these Big Read events and high-school and college students always reliably ask.) I do not want to talk about the novel as a love story, not tonight. I want to talk about the novel as a noir that surveys the rotten underbelly of the American Dream. Take that cheery assurance that Good readers make good citizens and stuff it down a drain. Billy Wilder’s off-kilter opening helps me make the case for this reading even before I open my mouth because, as the Perry audience can see for themselves, both Wilder’s and Fitzgerald’s pools are fed by the same dark sources.

I begin ticking off the clues: hard-boiled corruption infests the atmosphere of Gatsby. There’s bootlegging, the financial shenanigans of Gatsby and Wolfshiem and company, and the moral decay of Gatsby’s parties. “Think about it!” I exhort the good citizens of Perry. “All novels develop from a series of choices. Fitzgerald chose to make Gatsby a gangster. He could have affirmed the idea of a meritocracy by having Gatsby rapidly rise up the corporate ladder, be a banker or a grocery-store mogul like his own wealthy McQuillan grandfather. Instead, Gatsby has more in common with Don Corleone than he does Ben Franklin. Like The Godfather, The Great Gatsby skews the American dream of material success as the reward for honest hard work and enterprise.” (A few years later, Fitzgerald’s cynical move of making Gatsby “mobbed up” will strike me with fresh force. In the summer of 2013, I’ll take a tour of the Breakers, the Gilded Age mansion of Cornelius Vanderbilt II in Newport, Rhode Island. It’s a place whose real-life extravagance makes Gatsby’s fictional house seem like a starter mansion. As I walk through the morning room with its platinum wallpaper and stroll into Mr. Vanderbilt’s bathroom with its thick marble tub equipped with a special spout for heated salt water, the tour guide speaking through my headset earnestly assures me that Vanderbilt “worked very hard all his life.” We Americans want to believe that material excess is excused by very hard work; that the rich deserve their wealth. The Great Gatsby simultaneously affirms that idea—Jimmy Gatz’s youthful self-improvement list—and snorts at its naïveté.)

For the record, most of the novel’s other characters are also crooked in some way: Jordan Baker cheats at golf and tells lies about leaving roadsters out in the rain; Myrtle Wilson is an adulterous floozy; those “careless” Buchanans “smash up things and creatures.”11 Even Nick, as we’ve seen, isn’t completely on the level as a narrator. Add to all this moral ambiguity the seediness of so many of the settings in the novel: Myrtle and Tom’s love nest, Gatsby’s own decadent parties, the valley of ashes with the Wilsons’ dirty garage and Michaelis’s shabby Greek coffee place.

In addition to all the ways in which he plays with the conventions of a crime story in The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald wrote (and read) straightforward mystery tales too. His very first appearance in print was a short story for the September 1909 issue of Now and Then, a literary magazine put out by the St. Paul Academy. “The Mystery of the Raymond Mortgage” is a stiff-jointed Sherlock Holmes replicant. Fitzgerald later joked about a hole in the plotting: “Through some oversight, I neglected to bring the [mortgage] into the story in any form.”12 In the aftermath of Gatsby, Fitzgerald began toying with an idea for a novel (catchy working title: “The Boy Who Killed His Mother”) about a foul-tempered young man whose father is serving time in prison for a violent crime; our antihero is driven to commit the same act against his domineering mother. Fitzgerald struggled with this crime story for four years, on and off. Also in the immediate wake of Gatsby, Fitzgerald published an entertaining whodunit called “The Dance” in the June 1926 issue of Redbook magazine. Narrated by a woman, this short story devotes a good amount of space to singing the praises of New York City. “All my life,” the narrator tells us, “I have had a rather curious horror of small towns.… I was born in New York City, and even as a little girl I never had any fear of the streets or the strange foreign faces.”13 The narrator’s skittishness about the festering secrets of small town life is validated after another young woman is killed in the middle of a country-club dance. (Fitzgerald tries his hand here at a variant of the locked-room mystery and pulls it off. “The Dance” was deemed good enough by mystery aficionados to be reprinted in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine in 1953.)

I invite my audience in Perry that night to think of Gatsby’s connection to Dashiell Hammett’s 1930 hard-boiled masterpiece The Maltese Falcon, with its vision of debased knights chasing the grail of the fake falcon. While it’s not clear exactly when Hammett read Fitzgerald, we know he did, and the two men admired each other’s work. In 1936, while he was recuperating from that diving accident and trying to dry out at the Grove Park Inn in Asheville, North Carolina, Fitzgerald hired a private-duty nurse named Dorothy Richardson. He liked her and so put together one of his trademark “required-reading” lists for her. Amid titles like Stendhal’s The Red and the Black, Renan’s Life of Jesus, Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, and the complete poetic works of Keats and Shelley, Fitzgerald also listed The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett. Later on, in Hollywood, Fitzgerald made even more reading lists for his poorly educated lover Sheilah Graham. One of the many filed away in the Fitzgerald Papers at Princeton is entitled “Revised List of 40 Books.” This list includes additions scribbled in pencil by Fitzgerald, among them Proust (all seven volumes), Daisy Miller, Farewell to Arms, and Maltese Falcon. (Fitzgerald apparently committed the crime of petty theft in supplying the books he recommended to Graham. Don C. Skemer, curator of manuscripts at Princeton, where Graham donated her College of One books, tells me that many of them have MGM Library bookplates inside their front covers.)

Hammett, for his part, respected and defended Fitzgerald against those who jeered at him during his long personal and professional nosedive of the 1930s. In her notoriously unreliable memoir An Unfinished Woman, Lillian Hellman tells a story that I hope is true. On a night out on the town in 1939, Hellman and Hammett stroll into the Stork Club on Fifty-Third Street in New York City. They sit down at a table that gradually fills up with other folks, including Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway and Hammett get plastered and Hemingway starts showing off by trying to bend a spoon with only his muscular arm. He succeeds. As Hammett gets up to leave the table, Hemingway grabs his arm and challenges him to do the spoon trick. Hammett refuses, saying: “Why don’t you go back to bullying Fitzgerald? Too bad he doesn’t know how good he is. The best.”14 According to Hellman, Hemingway’s grip on Hammett’s arm loosens and his grin melts away.

Mutual admiration apart, what Fitzgerald and Hammett shared—along with so many of their Lost Generation cohorts—was a vision of the modern world where God was an empty illusion. Whether the object of worship is unmasked as a phony bird (the falcon) or whether belief itself is dismissed in a contemptuous phrase like Hemingway’s “Isn’t it pretty to think so?,” 1920s fiction in general, and the hard-boiled novel in particular, is godless and vacant.

Raymond Chandler, who, like Hammett and Fitzgerald, also served in World War I, nails this desolate vision at the end of his 1939 hard-boiled classic The Big Sleep when his detective hero Philip Marlowe says, “The world was a wet emptiness.” Take away the moisture, and Marlowe might as well be describing the valley of ashes. You hear the despair in Nick’s voice all the time he’s going back over Gatsby’s story: Daisy, the meritocracy, money, celebrity—they’re all gods that have failed Gatsby. Only Gatsby himself, in Nick’s understated testament of faith, “turned out all right at the end.”15 Chandler, by the way, was another hard-boiled detective writer who admired Fitzgerald. In a 1950 letter to the publicity director at Houghton Mifflin, Chandler commented that Fitzgerald:

had one of the rarest qualities in all literature, and it’s a great shame that the word for it has been thoroughly debased by the cosmetic racketeers, so that one is almost ashamed to use it to describe a real distinction. Nevertheless, the word is charm—charm as Keats would have used it. Who has it today? It’s not a matter of pretty writing or clear style. It’s a kind of subdued magic, controlled and exquisite, the sort of thing you get from good string quartettes [sic].16

Let’s turn away from the theological gloom that pervades Gatsby and its hard-boiled relations and consider a more tangible fixation they both share: cars. The Great Gatsby, like most hard-boiled detective stories and the film noirs that were made from them, is car crazy. The simple historical reason is that America in the 1920s was turning into a car culture; thanks to Henry Ford’s assembly lines, automobile ownership was becoming democratized. Ann Douglas writes that by 1929, one out of every five Americans had a car (as opposed to one out of thirty-seven Englishmen, one out of forty Frenchmen, and one out of forty-eight Germans).17 But in the hard-boiled universe, cars are not just modes of transportation, they’re fully loaded assault vehicles that allow their passengers to satisfy all manner of forbidden drives.

A woman in the driver’s seat is particularly bad news in a hard-boiled story. To the extent that Daisy embodies the newly acquired personal freedoms of the flapper—she drinks and sleeps around—she’s already a figure who makes many of the men in the novel edgy, even as they’re captivated by her. And let’s not forget that the liberated sportswoman Jordan Baker derives her androgynous moniker from two automobile makes: the Jordan sports car and the electric Baker.18 It’s when Daisy gets behind the wheel of Gatsby’s yellow roadster, however, that she indisputably achieves femme fatale status. To be behind the wheel is to be in control, and for a woman to occupy that place is as upsetting to the conventional hierarchies as that image of the white chauffeur driving the three African American passengers across the Queensboro Bridge. (“Don’t forget, I’m at the wheel now,” Ella Kaye ominously warns young Gatsby in the 1949 film.) Who can say for certain whether Daisy’s hit-and-run murder of Myrtle, her husband’s mistress, is just an accident or a subconscious homicidal drive realized? What is crystal clear is the fact that The Great Gatsby, like so many hard-boiled novels and film noirs, is obsessed with the image of a woman behind the steering wheel. (The iconic noir woman-driver image is Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity smiling behind the wheel in a sexually satisfied way as fall guy Fred MacMurray strangles her husband.)

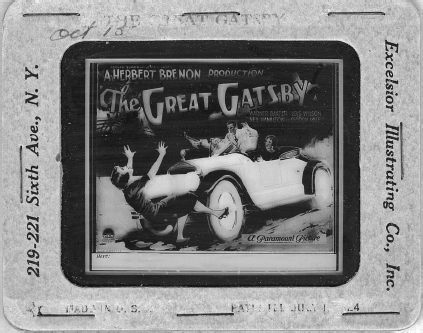

A glass slide from the 1926 silent movie. (MATTHEW J. & ARLYN BRUCCOLI COLLECTION OF F. SCOTT FITZGERALD, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA LIBRARIES)

Early illustrators of The Great Gatsby recognized the sexually transgressive seating arrangements within “the death car,”19 as the tabloids call Gatsby’s yellow roadster. In the Bruccoli Collection of Fitzgerald’s papers, manuscripts, and assorted other material at the University of South Carolina, there’s a glass slide of a marvelous advertising still from the lost 1926 silent movie of The Great Gatsby; it depicts Myrtle Wilson falling backward under the wheels of Gatsby’s car as Gatsby himself is leaping up, aghast, in the passenger seat. Daisy, in contrast, stares grimly ahead, hands gripping the steering wheel, pedal to the metal. In the Fitzgerald Papers at Princeton, there’s a brilliantly comic (but unattributed) newspaper cartoon pasted into the Great Gatsby scrapbook that Fitzgerald kept of reviews and interviews. The cartoon captures the final act of Gatsby in one frame: a cloche-hatted Daisy sits behind the wheel of a gigantic jalopy that is rolling over a mountainous (but strangely unfazed) Myrtle. Behind the two women, Gatsby’s corpse lies stretched out on the pavement, and George Wilson is about to blow his brains out. These 1920s illustrators wanted to grab their viewers’ attention; unlike us English teachers, they knew better than to wax rhapsodic about the novel’s language or the larger American themes in the story. Instead, they went straight for sensation, and nothing was more sensational than the image of an out-of-control woman driver.

Gatsby itself swerves fully into pulp style at the time of Myrtle’s murder: the episode is told from the points of view of a variety of witnesses. The only time the language of The Great Gatsby becomes ugly is in the jarring sentences that describe Myrtle’s broken body: “her left breast swinging loose like a flap,” her mouth “ripped at the corners.”20 It takes a while for the novel to catch its breath, recover from this pulp crudeness, right itself, and get back to poetry. Writing to Max Perkins from Rome in January of 1925, Fitzgerald strenuously protested a softening of Myrtle’s gory death: “I want Myrtle Wilson’s breast ripped off—it’s exactly the thing.”21 I think of how, as so often in the larger story of The Great Gatsby, life followed art when a mentally ill Zelda in the fall of 1929 grabbed the steering wheel away from Scott on that road in France and tried to veer toward their deaths. That particular swerve was never righted.

I opened my talk in Perry that night with the clip from Sunset Boulevard because one of the most crucial connections between The Great Gatsby and the hard-boiled novels and film noirs is that image of going under, drowning (even if, technically speaking, the bullets finished off both Jay Gatsby and William Holden’s Joe Gillis first). Hard-boiled and noir characters are always going belly-up in pools (Ross Macdonald’s Black Money), oceans (James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity), oil sumps (Rusty Regan in The Big Sleep), and lakes (Chandler’s The Lady in the Lake). They’re always dissolving into sweat (the 1950 Rudolph Maté film D.O.A.) and tears (Michael Curtiz’s 1945 film of Mildred Pierce). They also all uniformly drown themselves in liquor. It makes complete noir poetic sense that when Gatsby finally takes his very first dip of the season in his pool, he promptly dies. “Poor dope, he always wanted a pool.” Dreamers in the hard-boiled universe are always poor dopes. There’s a line that perfectly explains why; it lodged in my brain years ago and comes from a hard-boiled novel or a noir or a critical book or an essay and has eluded all my attempts to track down its source. Still, since that line specifically details the way in which these guys are poor dopes, I’m going to go ahead and quote it: “They chased their dreams to the edge of the Pacific, only to be conned one more time.”

Obviously, Gatsby doesn’t go west to chase his dream (although he does wash up in West Egg); instead, he chases his dream to the edge of the Atlantic, “the great wet barnyard of Long Island Sound.”22 Then he’s conned one more time—by his reading of Ben Franklin, by Daisy, by America—and goes under. Since Gatsby is not the story of one man’s rise and fall but, in its prescient way, of a national “shipwreck” that’s looming on the outer edge of the 1920s, there’s a sense in which he, like almost everyone in this novel, is sunk from the very beginning. That initial scene in the Buchanans’ house reads like the literary equivalent of Curtiz’s great noir rendering of James M. Cain’s Mildred Pierce. In that movie’s opening shot, Mildred’s beach house is filmed to look as though it’s underwater, suggesting the impending oblivion at the end of the story. Listen, once more, to how carefully Fitzgerald describes the damp décor in the Buchanans’ own “beach house”: “A breeze blew through the room, blew curtains in at one end and out the other like pale flags, twisting them up toward the frosted wedding-cake of the ceiling, and then rippled over the wine-colored rug, making a shadow on it as wind does on the sea.”23 Can you hear the echoes of Homer’s “wine-dark sea” in those lines? The revelers at Gatsby’s party in chapter 2 also are described as though they’re under the waves, drowning in liquor:

The groups change more swiftly, swell with new arrivals, dissolve and form in the same breath—already there are wanderers, confident girls who weave here and there among the stouter and more stable… and then excited with triumph glide on through the sea-change of faces and voices and color under the constantly changing light.24

Nick, talkative though he may be, also belongs to this pale company of the drowned: like Holden’s Joe Gillis, Nick is a dead man talking. Physically, he may still be breathing, but emotionally, he’s used up. (Baz Luhrmann’s otherwise silly champagne bubble of a film wisely latched onto this empty aspect of Nick when it placed him at the opening of the film in a sanitarium recovering from a nervous breakdown and “dipsomania.” In what is surely meant to be a doff of the hat to Fitzgerald’s legendary editor, Luhrmann calls this joint the Perkins Sanitarium.) And what does Nick talk about with his precious breaths? He tells a story about his friend Jay Gatsby, who was a fellow soldier in World War I. As I’ve said, the modern use of the term hard-boiled came out of that war, and in almost every classic hard-boiled story, the most stable and intense relationship is not between the hero and the woman he loves but between two men, comrades in arms. The 1949 Gatsby movie stresses the buddy element running through the story by surrounding Ladd’s Gatsby with gangster underlings who’d served with him in the Great War. Hard-boiled novels and the noirs that were made from them are male buddy stories that explore what makes a man a man in a newly fallen world.

That Tom Buchanan is the guy who’s cut out for this compromised world (given that he strides off, untouched, at the end of The Great Gatsby) is a grim predictive vision of the “hollow men”—all show, no substance—who are primed to flourish in the modern age. Before Gatsby’s delayed entrance into his own party and into the novel that bears his name, he flits around like a ghost. He abruptly materializes at Nick and Jordan’s table and, a chapter later, he’ll just as suddenly vanish on Nick in that Forty-Second Street lunch cellar after Nick introduces him to Tom Buchanan. Gatsby’s very first silent apparition in the novel—at night, on his lawn—establishes the eerie postmortem atmosphere. Remember, Gatsby is dead already when Nick begins telling us his story. After taking his eyes off Gatsby for a moment, Nick finds “he had vanished, and I was alone again in the unquiet darkness.”25

Fitzgerald knew that he had created a story in which the primary relationship was between two men. Writing to H. L. Mencken in a letter dated May 4, 1925, Fitzgerald, in his typically spelling-challenged style, confessed that “the influence on it has been the masculine one of The Brothers Karamazof, a thing of incomparable form, rather than the femineine one of The Portrait of a Lady.”26 When Gatsby turned out to be a commercial failure, Fitzgerald quickly came to believe that he had “paid” for making Nick and Gatsby the focus of the novel. In a letter to Maxwell Perkins dated April 24, 1925, Fitzgerald bemoans weak sales and blames the title, which he says is “only fair, rather bad than good… And most important—the book contains no important woman character and women controll [sic] the fiction market at present.”27

Hard-boiled fiction is a man’s world; the only big roles for women are the femme fatale (Daisy) and the corpse (Myrtle). Not only are these male buddy stories, they’re stories about soldiers. The classic hard-boiled novels of the 1920s and 1930s were written by men who had served in the war. The most prominent example is Raymond Chandler’s masterpiece The Big Sleep, where Philip Marlowe and the other tough guys consistently address each other as “soldier.” The hard-boiled formula also venerates older “manly men” like Gatsby’s mentor, Dan Cody, that “pioneer debauchee” whose photograph hangs on the wall above Gatsby’s desk. In Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op stories and novel, the Op works for a detective agency headed by a boss known only as the Old Man. To cite The Big Sleep again, Philip Marlowe risks life and limb because he comes to respect his elderly (military) client General Sternwood. Hard-boiled novels stress the loyalty that good men show to each other—certainly a central motif in Gatsby. Recall that scene on the final page of the novel where Nick visits Gatsby’s “huge incoherent failure of a house”28 on the night before he returns to the Midwest. He tells us that what we would call a graffiti artist has been at work: “On the white steps an obscene word, scrawled by some boy with a piece of brick, stood out clearly in the moonlight, and I erased it, drawing my shoe raspingly along the stone.”29 That’s Nick’s job as narrator: to clean up the blots on Gatsby’s name. If not for Nick’s overwhelming loyalty to his fallen friend, there would be no story.

So does Nick want to be more than buddies with Gatsby? Given the explosion of queer studies in the academy over the past two decades, it’s become commonplace to talk about The Great Gatsby as an unrequited homosexual love story in the Death in Venice line. There’s certainly enough support in the novel for the homosexual reading of Nick. After most public Gatsby lectures I’ve given in the past few years, someone will pipe up and ask about that curious moment at the end of chapter 2 where an underwear-clad Nick and the photographer McKee wind up together. Just as suggestive is the fact that a phallic joke precedes that scene: Nick and McKee step into the apartment-house elevator, and the “elevator boy” snaps at McKee, “Keep your hands off the lever.”30 Nick’s relationships with women are brief and evasive and he guardedly falls for Jordan Baker, whose look, name, and sporty occupation are mannish in the context of the 1920s.

I think my definitive response to the Gay Gatsby readings is “Could be.” I’m so wed to the reading of Gatsby as a hard-boiled novel that Nick’s love for Gatsby seems in keeping with the bromance nature of that genre. To put it another way, Nick doesn’t have to be gay to explain why he’s in thrall to Gatsby’s memory. If he did, then Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and Mickey Spillane—each of whom risks his life to do right by a murdered partner or male friend—would also have to be gay… as, admittedly, many queer theorists of detective fiction have argued is the case. That Nick loves Gatsby is a certainty beyond dispute. Love and loyalty are what motivate him to tell Gatsby’s story two years on. To me, what’s even more crucial than Nick’s sexuality is this realization that, like every noir narrator worth his near empty bottle of gin, Nick tells us a story that has already happened. He’s “borne back ceaselessly into the past.”31

There you have it: the big reason why it matters for us readers to recognize Gatsby’s hard-boiled identity. Since Nick’s story is retrospective, the outcome is already decided. Despite the hopes for civic uplift that the NEA might have nurtured in choosing The Great Gatsby for the Big Read, Fitzgerald’s masterpiece is, in many ways, a very un-American novel indeed. Reinvention? No dice. The past always reaches out to grab the dreamer, and the poor dope always drowns in the end. (The title of the classic 1947 noir starring Kirk Douglas, Robert Mitchum, and Jane Greer could have been a good alternative title for Gatsby: Out of the Past.) As literary critic Morris Dickstein has pointed out, the essential movement of Gatsby’s story is backward, “like an inquest.”32 We start with Nick’s present-time narration in 1924, then we’re drawn backward to the summer of 1922, then to Gatsby and Daisy’s meeting in 1917, and, finally, to those go-for-broke last paragraphs that telescope all the way back to “the old island… that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes—a fresh, green breast of the new world.”33

The shadow side of The Great Gatsby’s all-American story—the one that preaches a chamber of commerce sermon about limitless potential—is a noir with a distinct No Exit atmosphere to it. What Raymond Chandler dubbed “the smell of fear” wafts into the novel from its earliest pages, in which the final disasters are foretold. Take the fact that there are not one but two car crashes ominously preceding the hit-and-run that kills Myrtle and, essentially, Wilson and Gatsby as well. In chapter 3, at the end of the first party scene, Owl Eyes emerges from a wrecked coupe that’s lost a wheel in Gatsby’s driveway. As the crowd of drunken stragglers blames Owl Eyes for the accident, he protests that: “I wasn’t driving.” And, indeed, at that same moment, the drunk driver extricates himself from the car. Anyone who’s read The Great Gatsby at least once before should sense something familiar in this scene involving a car crash and wrongly accused driver: it anticipates Gatsby chivalrously taking the blame for Daisy’s carelessness at the wheel that costs Myrtle her life. One chapter later, we hear about yet another car wreck in which, once again, a wheel is lost. This time, infidelity is involved. Shortly after his marriage to Daisy, Tom and a chambermaid from the Santa Barbara Hotel are in a smashup. Since only her arm is broken, that chambermaid gets off more lightly than poor Myrtle will. Car references abound, but the other one that I’ll single out is that conversation—in hard-boiled patois—that Nick and Jordan have about the breakup of their relationship. Jordan reminds Nick of a conversation they once had about driving a car. “You said a bad driver was only safe until she met another bad driver? Well, I met another bad driver, didn’t I?”34 “Bad driving” is clearly a code, tough talk for reckless behavior. The instances of bad driving that anticipate the car wreck that kills Myrtle in chapter 7 give it a fated feel.

Fate is the essential ingredient in hard-boiled and noir narratives; so are coincidence and repetition. This short novel twice tells the story of Gatsby and Daisy’s initial meeting; scenes are repeated, such as the party at the Buchanans’ house that opens chapters 1 and 7. Even objects make repeated appearances: Meyer Wolfshiem’s nasty cuff links and Daisy’s pearl wedding necklace are reprised in Tom Buchanan’s final appearance in the novel when he goes into that jewelry store on Fifth Avenue (probably Tiffany) “to buy a pearl necklace—or perhaps only a pair of cuff buttons.”35 Christopher Hitchens wrote a gorgeous appreciation of The Great Gatsby in the May 2000 issue of Vanity Fair, but Hitchens got one thing wrong. Talking about how the novel rises above its “abysmal weakness of plot and plausibility,” Hitchens offered this instance of a hard-to-swallow plot device: “A man of Gatsby’s supposed force and vitality just takes a house and waits for the girl to come, luckily discovering after brooding at length on a green light that the adored one’s cousin lives next door!”36 To which I protest, “But of course! It’s Fate!” The convoluted plots of classic hard-boiled novels and noirs rest on such coincidences that are proof, not of a benevolent God (as they would have been in the nineteenth-century novel), but of ultimate dead ends. Coincidence in Gatsby speaks to the foolishness of embracing that other late Victorian chimera: the notion that “I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul.”37 All appearances to the contrary, Gatsby is stuck in the passenger seat, not sitting behind the steering wheel, of his own story.

I think Fitzgerald absorbed the techniques and the attitude of the emerging genre of hard-boiled fiction while he was intermittently living in and close to New York City from the late winter of 1919 to the spring of 1924. So much of the sturdy fabric of Gatsby—the criminal underworld, the tough-guy lingo, the obsession with the past, the violence, the doom-laden sense of fated-ness, the voice-over narration, the death by drowning—were staples of the hard-boiled genre that was hatched in America and, specifically, in New York City, in the twenties. Many of the classic noirs of the 1940s and 1950s would take their stories from those hard-boiled tales, including the Alan Ladd Gatsby of 1949. The hard-boiled element in The Great Gatsby accounts for some of the dark magic of this very strange and un-American Great American Novel.

After The Great Gatsby was published in April of 1925 and then quietly sank under the waves by autumn of that year, Fitzgerald, who was living in Paris with Zelda and Scottie, answered a fan letter sent to him by New York critic, Marya Mannes, who must have also said something enthusiastic about her hometown:

You are thrilled by New York—I doubt you will be after five more years when you are more fully nourished from within. I carry the place around the world in my heart but sometimes I try to shake it off in my dreams. America’s greatest promise is that something is going to happen, and after awhile you get tired of waiting because nothing happens to people except that they grow old.38

Fitzgerald missed out on the chance to grow old—although, as we know from Nick’s self-pitying birthday dirge in Gatsby, both he and his creator regarded thirty as the absolute end of youth. When Fitzgerald and his family returned for good to America in 1931, he and Scottie mostly lived in and around Baltimore while Zelda spent time as a resident or outpatient of various sanitariums. Then, in the summer of 1937, Scottie was sent to boarding school and, during vacations, to live with the family of Fitzgerald’s literary agent, Harold Ober, while Fitzgerald moved to what had become America’s premier hard-boiled city, Los Angeles. He was lured out there by a six-month contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer to work on scripts. This was his third trip out to work for the movies, which chewed up and spit out many a fine writer. Like a hard-boiled fall guy, Fitzgerald would “chase [his] dreams to the edge of the Pacific, only to be conned one more time.”

In Hollywood, the story of the last act of Fitzgerald’s life acquired many of the details—if not the full-blown plot—of a classic noir. When he first moved out to Los Angeles, he took a furnished apartment at the tawdry Garden of Allah complex. Owned by silent film star Alla Nazimova, the Garden of Allah was home to a lot of hard-drinking writers (Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker) and movie stars (Errol Flynn, Greta Garbo, Humphrey Bogart) and was distinguished by its fabled pool, constructed in the shape of the Black Sea to commemorate Nazimova’s Russian roots. In those early months Fitzgerald was unmoored and lonely; there are accounts of him eating by himself at the MGM commissary and there’s also this sad little postcard he sent to himself: “Dear Scott—How are you? Have been meaning to come in and see you. I have [sic] living at the Garden of Allah. Yours, Scott Fitzgerald.”39

Life picked up, however, when he fell for a young blonde with a dappled past: the fledgling Hollywood gossip columnist Sheilah Graham who, like Jay Gatsby, also “sprang from [some] Platonic conception”40 of herself. In his unfinished Hollywood novel, The Love of the Last Tycoon, Fitzgerald wrote that his hero, Monroe Stahr, was attracted to the lovely Kathleen Moore because she had “the face of his dead wife.” Graham bore a resemblance to Zelda and came to feel that Fitzgerald was reliving his youth with her.41 Graham would eventually write five books about their three-and-a-half-year affair; her son (allegedly with Hollywood star Robert Taylor) wrote still another.

Graham had something of the aura—and the personal history—of a 1930s tough dame. In addition to her son from her liaison with Taylor, she also had a daughter out of wedlock, Wendy Fairey, with the British positivist philosopher A. J. Ayer. Before Graham met Fitzgerald, she’d been in an open marriage: her impotent, older husband encouraged the eighteen-year-old Graham to date the wealthy stage-door Johnnies who flocked to see her perform as a chorus girl. By the time she arrived in Hollywood, Graham was already working her way up the social ladder—she’d gotten engaged to the Marquess of Donegal. Unlike Zelda, who’s been turned into something of a martyr figure by some of her admirers, Graham was no victim. Much as she loved Fitzgerald (there’s a 1939 codicil to her will in one of the archival boxes in Princeton in which she leaves everything to him), she also profited by writing about their relationship for decades after his death.

But Graham also seems seductively forthright in her accounts of life with Scott; indeed, she won me over halfway through Beloved Infidel, her first and best-known memoir about their romance. I wanted to meet up with her at Musso and Frank’s and dish over martinis. Graham’s voice is smart and disarming, and her books abound with the kind of small details that make a subject come alive. Fitzgerald, we learn, liked canned turtle soup for lunch and Hershey bars for a snack. We also hear about his ugly behavior when drunk. Off the sauce, he drank gallons of sweetened coffee and Coca-Colas; at night he put himself to bed with sleeping pills and popped Benzedrine to wake up in the morning. “At present, he is drinking at least a pint of gin a day,” Graham writes in notes she made to herself in 1939 prior to what must have been a tense conversation with Fitzgerald’s doctor. “It is stupid for you to regard me as the villainess of the piece because I can’t bear to see him drunk.”42 Graham seems to have genuinely cared for Fitzgerald in both a romantic and nurturing way. In the spring of 1938, she found him a beach house out in Malibu; she thought the salt air would restore him to health and she wanted to distance him from his drinking buddies. Fitzgerald, though, hated the damp and avoided the sun. According to Graham, he “never swam or even waded in the inviting surf.”43 Here’s how she describes Fitzgerald at the beach:

“Scott, at Malibu. He is in an ancient gray flannel bathrobe, torn at the elbows so that it shows the gray slip-over sweater he wears underneath. He has the stub of a pencil over each ear, the stubs of half a dozen others—like so many cigars—peeping from the breast pocket of his robe. One side pocket bulges with two packs of cigarettes.”44

How odd. There are so many photos of Fitzgerald in his prime in bathing costumes, sitting, often with Zelda and Scottie, by a pool or an ocean. Maybe that diving accident in 1936 ruined his love affair with swimming. Or maybe, as Fitzgerald neared the end of his life—as he became more exhausted by his own personal struggle to keep his head above water—he regarded the ocean as a more threatening force. I think of a similar story about the aging Raymond Chandler living with his dying wife, Cissy, in their house in La Jolla overlooking the ocean. As Judith Freeman recounts in The Long Embrace, her superb book on Chandler and Cissy, a visitor paid a call at the beach house and noticed that Chandler’s desk in his small study was turned toward an interior courtyard window, away from the fabulous ocean view. When the visitor asked Chandler about the odd position of the desk, he said he didn’t like the ocean: “Too much water, too many drowned men.”

Fitzgerald moved from that beachfront rental house back to Hollywood. He died of a heart attack (possibly his third) on December 21, 1940. By the time of his death, because of his weakened condition, he had moved in with Sheilah Graham to her ground-floor apartment on North Hayworth Avenue, although, for appearances’ sake, he kept his apartment at 1403 North Laurel Avenue. The past repeated itself in that address: Fitzgerald had been born on Laurel Avenue—in St. Paul—forty-four years earlier. North Laurel Avenue in Los Angeles is half a block south of Sunset Boulevard. Of course, that proximity would have meant nothing to Fitzgerald or any of his loved ones in 1940, but I wonder if Billy Wilder, who was acquainted with a washed-up writer named F. Scott Fitzgerald during that Hollywood period, might have been taking mental notes.

Scott and Scottie in the Mediterranean. (MATTHEW J. & ARLYN BRUCCOLI COLLECTION OF F. SCOTT FITZGERALD, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA LIBRARIES)