5

“Here Lies One Whose Name Was Writ in Water”*

I live in Washington, DC, a city riddled with places that are off-limits to average citizens: restricted corridors of power, hidden tunnels and bunkers. My chief entrée into these places is through suspense fiction, but once in a while, I get a taste of what it’s like to be an insider. So it was that on a bright October morning in 2012, I was led onto an elevator in the Library of Congress and taken down, down, down, to the underground stacks, a staff-only zone. It’s very cold down there and dim—a subterranean library with none of the grandeur of the public rooms above. A worker wearing earbuds and pushing a squeaky metal cart full of books occasionally walks by; otherwise, it’s silent as the proverbial tomb. I felt like Nicholas Cage in those National Treasure movies, poking around far beneath official historic sites in order to ferret out clues to mysteries of national importance.

The particular mystery I was trying to solve that day was this: How did The Great Gatsby, all but dead itself after Fitzgerald’s death, come roaring back to life so forcefully that within two decades it infiltrated the syllabi and textbooks of high schools and colleges across the land and was embraced as one of our Great American Novels? I thought the Library of Congress should be able to provide some answers since, after all, it is the nation’s premier research library. It’s also a tough place to navigate alone. Luckily, since the day I first stepped into the cathedral-like main reading room, outfitted with my preferred old-school tools of number 2 pencils and legal pads, I’ve had a top-notch guide. Abby Yochelson is a reference librarian at the Library of Congress who specializes in literary research. She’s about my age and elegant, with salt-and-pepper hair and a stylish wardrobe of shawls and sweaters she wears against the library’s chill. With her calm approach to research, Abby neutralizes my terror of what I’ve come to think of as the Blob—the spreading ooze of Fitzgerald books, articles, films, and artifacts that expand exponentially with each passing year. (Maybe, as Abby eventually confesses to me, the fact that she just doesn’t get the magic of The Great Gatsby inoculates her against feeling overwhelmed by the novel itself and the sheer volume of criticism and other material it’s generated.) After our first meeting, in the fall of 2011, Abby carried out a targeted search in the Library of Congress’s online catalog. The results listed more than fifty-five works—primarily books—on the subject of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s life alone; another seventy-one under the subheading “criticism and interpretation”; and another sixty-plus exclusively on The Great Gatsby. She helped me put together a dense list of reference works on the 1920s, a compendium of contemporary book reviews, a catalog of newspapers and popular magazines of Fitzgerald’s time, and a summary of the TV, radio, and motion-picture adaptations of Gatsby as well as of Fitzgerald’s other novels and stories. These tallies don’t take into account all the thousands upon thousands of scholarly articles on Fitzgerald nor the various editions of the primary works themselves. The big kahuna of the latter is the Cambridge Edition of the Works of F. Scott Fitzgerald series, which began to appear in 1991—starting with The Great Gatsby. It will ultimately number seventeen volumes. Abby also recommended that I log on to the WorldCat online site, which itemizes the collections of seventy thousand libraries worldwide. Just doing a targeted search for books with the subject line “The Great Gatsby,” I came up with 250 titles. Had I but world enough, and time.

Critics began taking second looks at Fitzgerald’s work even before his coffin was lowered into the ground (for the first time). The New York Times obituary set the patronizing tone for the first wave of Fitzgerald reevaluations, which saw him as an author defined by the Jazz Age: “Mr. Fitzgerald in his life and writings epitomized ‘all the sad young men’ of the post-war generation.… Roughly, his own career began and ended with the Nineteen Twenties.… The promise of his brilliant career was never fulfilled.”1 As Arnold Gingrich, Fitzgerald’s editor at Esquire, complained to Sheilah Graham, most of the obituaries, respectful as they were, barely mentioned The Great Gatsby.2 The one exception to the general tone of polite wistfulness was the story filed by the ultraconservative Hearst columnist Westbrook Pegler on December 26, the day before Fitzgerald was buried. Pegler’s ranting lede, decrying the hedonism of the 1920s, anticipates the kind of criticisms the silent majority would level against those darn hippies during the 1960s: “The death of Scott Fitzgerald recalls memories of a queer brand of undisciplined and self-indulgent brats who were determined not to pull their weight in the boat and wanted the world to drop everything and sit down and bawl with them.”3 Posthumously, at least, Fitzgerald found himself in good company: Pegler made a career out of damning Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, the Supreme Court, the New Deal, and (big surprise) labor unions.

Spurred on in part by Pegler’s nastiness, critics such as Malcolm Cowley, Stephen Vincent Benét, Paul Rosenfeld, and Glenway Wescott wrote evocative reconsiderations of Fitzgerald over the next few years and published them in the general-interest literary magazines that flourished in mid-twentieth-century America. Thirty of those essays would reappear in the first essay collection devoted to Fitzgerald: F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Man and His Work, edited by Alfred Kazin. (Curiously, the publisher of this 1951 essay collection, the World Publishing Company, otherwise specialized in dictionaries and Bibles.)

To this day, I think Fitzgerald brings out some of the best critical writing in his sympathetic readers. Here, for instance, is Lionel Trilling on Fitzgerald: “Fitzgerald lacked prudence, as his heroes did, lacked that blind instinct for self-protection which the writer needs and the American writer needs in double measure. But that is all he lacked—and it is the generous fault, even the heroic fault.”4 I also think Fitzgerald infiltrated some of his admirers’ writing in less direct ways. In 1951, Alfred Kazin published his book A Walker in the City, one of the great memoirs about twentieth-century New York. Throughout, Kazin, who grew up the child of immigrants in Brownsville, Brooklyn, looks over the East River to what he repeatedly calls “Beyond.” “Beyond” is Manhattan, the land of success and completely acculturated Americans. You can’t tell me Kazin wasn’t thinking of Gatsby when he wrote those passages suffused with yearning for something across the water, out of reach.

In addition to the supportive critics, Fitzgerald’s close friends rallied round after his death, concerned that his name, like Keats’s, was also “writ in water.” Edmund Wilson, acting at the behest of Maxwell Perkins and Howard Ober, labored over the unfinished draft of The Love of the Last Tycoon. In 1941 Scribner’s brought out Wilson’s edition of the fragment under the title The Last Tycoon. That volume also included The Great Gatsby and some of Fitzgerald’s most famous short stories. In 1945, against Perkins’s wishes, Wilson’s edition of The Crack-Up came out. The Crack-Up essays clearly resonated with at least one segment of readers in the 1930s: the clinically depressed. The Fitzgerald Papers at Princeton University yield up a number of fan letters from readers battling their own demons—some of them are, in fact, writing from sanitariums. Many of these fellow sufferers had read the Crack-Up essays in Esquire; others, the awful Michel Mok 1936 birthday interview in the New York Post. Uniformly, these letters are poignant in their generous desire to “buck up” Fitzgerald and assure him that “your best years are ahead of you.”5

Another old friend of Fitzgerald’s youth, Dorothy Parker, selected the writings—including The Great Gatsby—that would be in The Viking Portable Library: F. Scott Fitzgerald, which came out in 1945. That edition included a beautiful tribute to Fitzgerald by his buddy John O’Hara. Another (sometime) buddy, John Dos Passos, contributed to a 1946 book called I Wish I’d Written That an excerpt from the beginning of chapter 3 of The Great Gatsby.

In 1950, screenwriter Budd Schulberg wrote a bestselling novel about Fitzgerald, The Disenchanted. (Schulberg had accompanied Fitzgerald on a disastrous trip to Dartmouth in 1939 to work on the script for a college movie called Winter Carnival. Fitzgerald drank so heavily during that trip that he was fired by his studio bosses at United Artists.) The Disenchanted fixed in the public’s mind the popular image of Fitzgerald as a tragic drunk; in 1958, it was turned into a Broadway play with Jason Robards as the Fitzgerald character. In 1951, another literary compatriot, Malcolm Cowley, introduced a collection called The Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald, and also in that year, the first biography of Fitzgerald appeared: Arthur Mizener’s The Far Side of Paradise.

There’s a pattern to this reconstruction of Fitzgerald’s literary reputation: Fellow writers, most of whom knew Fitzgerald pretty well and who still had influence within the literary culture, keep writing about him and his work. Curiosity and reconsiderations of Fitzgerald then spread throughout the larger culture. The years 1950 and 1951 seem critical. Schulberg, Mizener, the Kazin essay collection, and the Cowley short-story volume all appear during this period. What else is going on in America then that might have triggered this Fitzgerald Revival? Here’s one hypothesis: This is a time of Cold War calcification, when intellectuals are being asked whether they are on the side of America or its Soviet foe. Might the American qualities of The Great Gatsby and even Fitzgerald’s lesser work have somehow resonated again at this point?

Sheilah Graham entered the arena somewhat belatedly in 1958 with her bestselling memoir Beloved Infidel, made into a movie that same year with Deborah Kerr as Graham and a wooden Gregory Peck as Fitzgerald. A few years later, in 1964, Ernest Hemingway’s posthumously published memoir A Moveable Feast painted a devastating picture of Fitzgerald as a weakling, in thrall to a jealous and insane wife. In addition to tweaking the “rich are different from you and me” anecdote so that he got to deliver the triumphant punch line, Hemingway also told a humiliating tale about taking Fitzgerald on a museum expedition to look at nude classical statues in order to allay his alleged anxiety over the size of his penis. That gossipy swipe at Fitzgerald sparked a startling colloquium, of sorts, on the pages of Esquire magazine: the subject wasn’t Fitzgerald’s fiction but his anatomy. Sheilah Graham and Esquire editor Arnold Gingrich contributed their expert opinions.6

These are some of the first stirrings of what the stalwart Frances Kroll Ring derisively called the “Fitzorama.”7 Undeniably, these books, articles, and films were crucial to kick-starting the Fitzgerald Revival, although, as Fitzgerald scholar Ruth Prigozy points out, there wasn’t much to “revive,” since Fitzgerald had never gotten his proper critical due the first time round. In the basement of the Library of Congress that fall morning, however, I’m trying to trace something wider and more elusive. I want to get a sense of how appreciation for Fitzgerald rippled out of this relatively closed circle of journalists and writers, critics and scholars. How did The Great Gatsby, in particular, come to be embraced not just by “the smarties” (to use the poet Stevie Smith’s mocking term) but also by civilian readers? Hence my expedition down into the bowels of the Library of Congress with the intrepid Abby.

In the subbasement of the Thomas Jefferson Building that October morning, Abby and I are carrying out a search that will no longer be possible just a few months from now. We’re combing through the metal stacks that hold the Library of Congress’s extensive collection of American literature anthologies—organized by series and date—trying to figure out when Fitzgerald’s writings first began to seep into high-school and college textbooks. Because of the crunch for space that bedevils the Library of Congress and so many other research libraries around the world, these musty literature anthologies are about to be shipped to an off-site storage facility where they’ll be shelved, not by subject, but by size. While we still can, Abby and I are doing something akin to prospecting for gold: we’re rifling through all of the volumes in chronological order, looking for a Fitzgerald “strike.” In the future, researchers who want to see these anthologies will have to request them from off-site, and, unless they’re willing to fill out hundreds of library call slips in the hopes of discovering the right volumes, they’ll have to know beforehand where the gold is located.

This search is making me sentimental for lost illusions. The American canon as presented in these mid-twentieth-century anthologies seems so stately and self-evident. Increase Mather begets Cotton Mather; Edgar Allan Poe spawns Edgar Lee Masters; the hellish visions of Jonathan Edwards bloom anew in Nathaniel Hawthorne. All through my college years, as an English major, I accepted without question this pale priestly procession of American literary genius. (It took groundbreaking literary feminists like Ellen Moers and Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar to knock some epiphanies into me in graduate school.) Except for a few outliers like Emily Dickinson and Louisa May Alcott—who couldn’t be considered geniuses because they were too “simple” (Dickinson) or wrote for children (Alcott)—everyone in the anthologies’ great-writers category was a white male. Things are so much simpler when everyone belongs to the same privileged club, even if, as The Great Gatsby reminds us, some white males are born members and others can’t even buy their way in.

Like its literature, America itself seems more “graspable” in these anthologies. Some of the volumes display quaint regional maps on the insides of their covers. If you’re of a certain age, you’ll remember these chamber of commerce fantasies in which Iowa is represented by a giant ear of corn, Texas by cattle, California by oranges, and New York by the Empire State Building (HOME AGAIN). I could get lost in this Lotus-Eaters’ Land of Literary Anthologies, but we’re pressed for time and it is seriously freezing down here. Abby and I are alternating crouching near the floor and stretching up to the tallest shelves, calling out dates—1950! 1961!—every time we find a Fitzgerald hit. I don’t remember who first shouted that particular “Eureka!” but, as it turns out, the earliest sighting of F. Scott Fitzgerald will be in an anthology that came out the year after his death. The 1941 edition of the decades-long-running Adventures in American Literature contains picturesque swatches of Americana cowboy songs and speeches by Robert E. Lee and “Negro” spirituals. In a summary essay introducing selections from contemporary literature, the Omniscient Voice of this volume declares: “A group who were in the heyday of youth during the twenties—Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos—represent rebellion against the manners and standards of conservative society. With the coming of the depression, the cynics of the ‘jazz age’ have given way.”8 Fitzgerald a cynic? Did the Omniscient Voice ever read Gatsby, not to mention almost everything else Fitzgerald ever wrote? My nostalgia for the simpler wisdom of the olden days is souring, fast.

Other than this single entry of his name, Fitzgerald simply doesn’t exist within the anthologies on the Library of Congress’s shelves from the 1940s. Hemingway, Faulkner, Dreiser, and O’Neill are all over the place, but no Fitzgerald. About nine months after this search, I’ll come upon an anthology from 1945 in Ernest F. Hollings Special Collections Library at the University of South Carolina. North, East, South, West bills itself as “a regional anthology of American writing” and mentions Fitzgerald as a regionalist: “F. Scott Fitzgerald was born in Minnesota in 1896, but almost everything he wrote… established him as an Easterner. He was the best of our writers of death and disenchantment in the twenties.”9 That odd labeling of Fitzgerald as a regionalist also pops up in the 1958 edition of Adventures in American Literature; once again, though, the anthology doesn’t bother to include an excerpt of Fitzgerald’s writing. To add insult to injury, that wedging of Fitzgerald into the regionalist subcategory follows a breathless paragraph applauding the work of the four Americans “who have won the coveted Nobel prize.”10 At that time, the fab four were Sinclair Lewis, Pearl Buck, William Faulkner, and Fitzgerald’s old “frenemy” Ernest Hemingway.

During the hours Abby and I spend underground mining the anthologies, our hands will become coated with a substance used by the Library of Congress in its “mass deacidification” process: the attempt to stabilize the poor-quality paper that makes so many nineteenth- and twentieth-century books crumble. But it’s worth a morning’s exposure to unknown chemicals to trace, however stumblingly, America’s dawning awareness of Fitzgerald. As I would have guessed, Fitzgerald gets included more frequently in the anthologies of the 1950s, while the 1960s volumes are so rich in mentions that they constitute a veritable Treasure of the Sierra Madre. “Winter Dreams” and “The Rich Boy” are Fitzgerald’s most anthologized short stories during those two decades, and, as a measure of how literary tastes change, the now diminished Beautiful and Damned is mentioned in a few anthologies as one of Fitzgerald’s best novels, while Tender Is the Night is frequently passed over in silence. What’s genuinely thrilling, though, is to catch the earliest glints of recognition that Fitzgerald—and The Great Gatsby—may be the genuine article: a great writer and his masterpiece.

The 1955 revised edition of The College Anthology of American Literature includes one of the earliest excerpts from Gatsby (the first party at Gatsby’s house, where he and Nick meet). The 1961 anthology American Literature: A College Survey senses something is a-stirring out there in the culture but doesn’t want to commit to the Fitzgerald Revival just yet. That anthology’s introduction to “Winter Dreams” impartially observes that Fitzgerald’s reputation “has undergone an extraordinary rehabilitation”11 during the past decade. The 1964 edition of American Literature also featured “Winter Dreams” and these restrained words of approval: “Within the past few years Fitzgerald’s novels and short stories have been rediscovered and he is again highly regarded as an outstanding American writer.… The Great Gatsby is Fitzgerald’s best novel.”12

One of Fitzgerald’s most brilliant advocates, the critic Alfred Kazin, served on an all-star editorial committee for the 1962 anthology Major Writers of America; not surprisingly, that anthology contained a generous and varied sampling of Fitzgerald (“The Rich Boy,” “Echoes of the Jazz Age,” “Ring,” “The Crack-Up”), as well as the verdict that The Great Gatsby was “probably Fitzgerald’s most flawless novel.”13 By 1968, our irrepressible old friend Adventures in American Literature declares that “The Great Gatsby is a novel some critics consider one of the best written in the twentieth century.”14 In academic-speak, that constitutes a rave.

The literature anthologies are a mineshaft down into the lost world of high-school and college classrooms of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. The other passageway would be through a wide sampling of the syllabi for English courses of those decades, but the Library of Congress doesn’t keep any collections of those. In fact, as Abby comments to me, even high schools and university departments that once maintained archives of course descriptions have switched over to online versions, so that any traces of what American students are reading in their English courses today are dispersed into the netherworld of the Internet. Everywhere I travel on my Fitzgerald investigations—physically and virtually—I ask about old syllabi and come up empty. A librarian at Teachers College, Columbia University, suggests that Fitzgerald may be mentioned in various old reading lists recommended by state and city school boards but says that I’d have to search for them hidden within the mammoth catalog listings for each individual school board. “This would be a rather onerous task!” she cheerily cautions.15 A kind curator at the New York City Municipal Archives does manage to exhume a set of guidelines, circa 1967, for curriculum development in “English Language Arts, Grades 5–12” in the New York City public-school system. The guidelines recommend The Great Gatsby as a promising title for a unit on “American man’s desire for success.”

I want to conclude this backward glance at how Fitzgerald became swiftly transformed from has-been to required reading by looking at two brief recollections by a significant mother-daughter pair. Sheilah Graham first read The Great Gatsby when F. Scott Fitzgerald gave her a copy during their Hollywood years together in the late 1930s; to do so, he had to special-order the novel from Scribner’s, since bookstores no longer had any of his works in stock. In the epilogue to her 1958 memoir, Beloved Infidel, Graham ruminates on a great shift in opinion on Fitzgerald that’s already happened:

If Scott were sitting beside me in my study on this September day, what would he think, how would he feel, to know his high estate in the world of letters today? That he has been the subject of critical studies, of a biography, a novel and a play; that his own stories have been dramatized for audiences of millions; that college students read him today not only because he is required reading in the universities but because they love his writing.16

One of the college literature professors who’s been teaching Fitzgerald to her students since the 1970s is Graham’s own daughter Wendy Fairey, an English professor at Brooklyn College. In her afterword to a new edition of College of One, another of her mother’s Fitzgerald memoirs, Fairey drolly comments:

Whenever I teach The Great Gatsby, as I have so many times in my forty years in the college classroom, I always wonder if I will tell the students my story.… Perhaps there’s been a little sag in the classroom energy and I turn to the story to reinvigorate us.… Interest at this point increases, usually mixed with a bit of understandable anxiety that an aging female professor, talking about her mother’s lover, has become unpredictable.17

There’s the Fitzgerald Revival in the classroom within the span of one generation as encapsulated in the experiences of Sheilah Graham and her English professor daughter. Were Fairey to rely only on family anecdotes to augment her interpretations of Gatsby, she’d be considered not only “unpredictable,” but quaint. (I doubt that she’s doing so; she’s identified as having served as director of Women’s Studies at Brooklyn College, which means she must be steeped in feminist theory, at least.) The Great Gatsby has been interrogated, deconstructed, diced, and spliced by academic critics with such gusto that a collection of all the scholarly articles ever published on just the novel could reconstitute the lost Bering land bridge between Alaska and Siberia. (The first dissertation on Fitzgerald that I’ve found was written in 1945. It’s called “The Development of the Fitzgerald Hero” and was written by a PhD candidate at Louisiana State University; by 1966, a scholar named Virginia Hallam submitted what looks like the first dissertation on the Fitzgerald Revival itself, “The Critical and Popular Reception of F. Scott Fitzgerald,” to the University of Pennsylvania, my alma mater. That dissertation lists the books and articles that constitute some of Fitzgerald’s academic revival without making any larger interpretations of why the revival happened in the first place.) In contemporary college literature classrooms, one popular textbook, Critical Theory: A User-Friendly Guide, uses The Great Gatsby as the bull’s-eye target against which to hurl all variant of contemporary critical theory: there’s postcolonialist Gatsby, structuralist Gatsby, queer theory Gatsby, semiotic Gatsby, cultural studies Gatsby, and on and on and on.

The full story of Fitzgerald’s “second act” in American life, however, is not confined to the clean, well-lighted spaces of bookstores, libraries, and classrooms. In fact, this part of that story doesn’t even take place in the United States but in American army bases, convoys, military hospitals, and even POW camps in Europe and the Far East. In a posthumous twist of fate he might have appreciated, former Second Lieutenant F. Scott Fitzgerald’s greatest novel, along with some of his best short stories, were sent into service overseas during World War II.

When I was growing up, I remember my father, who served on a destroyer escort during World War II, telling me about these “funny paperbacks” that were around back then. Like so many men of his generation, my dad didn’t talk a lot about his service, so anything he said about those war years stayed with me. It wasn’t until a few weeks after my descent into the Library of Congress stacks with Abby that I finally saw what my father meant by funny paperbacks.

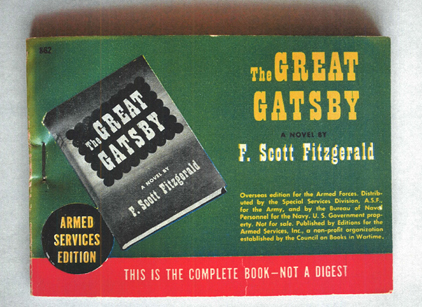

On this chilly morning a week before Thanksgiving, Abby and I have ascended to a Platonic readers’ heaven. The Rare Book and Special Collections reading room at the Library of Congress is a beautiful, wood-paneled space, modeled on Independence Hall in Philadelphia. I’m there to read two of the paperbacks in the library’s collection of Armed Services Editions, ASEs, the funny paperbacks that were distributed to the army and navy during World War II. The Library of Congress has the only complete set of ASEs in the world, all 1,322 titles.

The ASE program is often referred to as “the biggest book giveaway in world history.” Between the time it was launched, in 1943, to its end, in 1947, nearly 123 million books were distributed to U.S. troops overseas, everything from Hopalong Cassidy’s Protégé to Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa; Homer’s Odyssey to Webster’s New Handy Dictionary; Mary O’Hara’s My Friend Flicka to Melville’s Moby-Dick. The program was the brainchild of the Council on Books in Wartime, a group of publishers, librarians, and booksellers whose aim was to do their part for the war effort. Because boredom was an ever-present problem for America’s men in uniform when they weren’t fighting, the military brass was always looking for ways to keep up morale. The council hit on the idea of distributing inexpensive paperbacks to servicemen overseas, in military hospitals, and even in POW camps in Germany and Japan through an arrangement with the International YMCA.

The council, whose motto was Books Are Weapons in the War of Ideas, decided that in order to generate the hundreds of thousands of books needed—and to ensure that good books would be sent to the troops—it had to get involved in the actual production of paperbacks. (Earlier in the war, civilians had been urged to send books to the troops; thus, GIs and sailors got bombarded with duds from many an attic and basement.) Agencies from the army and navy, the War Production Board, seventy publishing companies, and more than a dozen printing houses, composition firms, and paper suppliers rallied to the cause. Portability was key: the books had to fit into servicemen’s pockets. The solution was to print the books on inexpensive paper on presses otherwise used to print the Reader’s Digest or pulp magazines. The smaller books would measure 5½ inches by 3⅞ inches; longer books would be 6½ inches by 4½ inches. Margins were practically nonexistent, and the text inside was printed in side-by-side columns on every page. (Ninety of the ASEs would eventually have to be condensed, Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone, Kathleen Winsor’s Forever Amber, and Moby-Dick among them.)

The design of the books was uniform: the rear cover featured sparkling copy about the story and the author; the front usually displayed a miniature of the book’s original cover. Since the ASEs weren’t meant to last for more than six or seven readings and since they were sent overseas, they wouldn’t flood the civilian market after the war. In the patriotic spirit of the war effort, authors and publishers each received a royalty of half a cent a copy, and five printing firms agreed to produce the books at less than half their normal percentage of profit. The cost of printing was six cents a copy. The very first ASE to roll off the presses in 1943 was The Education of Hyman Kaplan by Leo Rosten, a humorous send-up of a newly arrived immigrant’s experiences in English class at night school.

The semi-forgotten existence of the World War II ASE program is a feel-good revelation for those of us solitary bookworms who occasionally wonder if reading serves any larger societal purpose. Never before and never since in American history has love of country dovetailed so practically with love of books. The launch of the ASE program was heralded throughout 1943 on the pages of Publishers’ Weekly. Sometimes, the bookish enthusiasm of individual reporters verged on the delusional. A long article about the ASEs that appeared in September of that year talked about World War II as though it were the ideal opportunity for citizen soldiers to sit around and catch up on their reading:

Even after shipping overseas the soldier may have plenty of time on his hands. As the war has developed so far, comparatively few are engaged on actual battle fronts. Thousands find themselves on tropical isles—without Dotty Lamour—… Under these circumstances men become voracious readers. For subject matter, a letter from home takes first place; after that, almost anything but a missionary tract is acceptable.18

Hyperbolic literary fantasies aside, the simple testimony from servicemen of what those funny paperbacks meant to them is powerful. At a conference in honor of the fortieth anniversary of the ASEs, held at the Library of Congress in 1983, a World War II veteran named Arnold Gates recalled how during the Battle of Saipan he carried a copy of Carl Sandburg’s Storm Over the Land in his helmet: “During the lulls in the battle I would read what he wrote about another war and found a great deal of comfort and reassurance.”19 Years later, Sandburg inscribed the book for Gates. Some ASEs even reached the front lines: The task forces heading to the Marshall Islands, the Marianas, and Okinawa were given books as they departed from Hawaii.

The most mind-boggling mass distribution of ASEs occurred as American invasion forces were marshaling in southern England before crossing the English Channel on D-day. As Stephen Ambrose describes it in his sweeping history of the invasion, the camps where the troops were assembling were equipped with improvised movie theaters, great food (steak and pork chops, fresh eggs, even ice cream on an all-you-can-eat basis), and paperback libraries full of ASEs. General Eisenhower’s staff approved the distribution of a “copy of an Armed Services Edition… to each soldier as he boarded the invasion barge.”20 Soldiers reportedly discarded all nonessentials before crossing the Channel—spare blankets and souvenirs—but not a single book was left behind. The descendants of any D-day veterans who managed to hold on to their ASEs through Normandy Beach and beyond would now own a valuable collectible. Referred to as D-day books, those titles included The Grapes of Wrath, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Short Stories of Stephen Vincent Benét, Death Comes for the Archbishop, Cross Creek, and one of the most popular ASEs of them all, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.21

I’d love to know where the ASEs stored in archival boxes in the Library of Congress’s rare-book room have come from and under what circumstances they were read some seventy years ago. I’ve read accounts of ASE sets being dropped by parachute to remote islands in the Pacific and even brought up to front lines where battle-weary men would crawl on their bellies to get the books. Two thousand copies of each ASE title were set aside for distribution in prison camps in Germany and Japan. The two ASEs I’ve come to the Library of Congress to hold and read probably didn’t see action, but they may well have fueled a revolution. In 1945, after the surrenders of Germany and Japan, the Armed Services Editions printed and distributed 155,000 copies of The Great Gatsby and 90,000 copies of what was known as a “made edition” of The Diamond as Big as the Ritz and Other Stories. (Made editions were specially composed for the ASE program.) The Great Gatsby’s entry into World War II was—like Jay Gatsby’s entry into his own story—a bit belated and quiet. But, again like Jay Gatsby himself, the ASE seems to have made a lasting impression. Maybe the post-surrender distribution of Gatsby and Fitzgerald’s stories was fortuitous: in 1945, the millions of American servicemen stationed abroad might have had more time to read. Those servicemen would constitute an undreamed-of vast new audience for Gatsby. Recall that Fitzgerald, even in his most ambitious moments in 1925, fantasized about selling only around 70,000 copies of the novel. Let’s do the math: 155,000 ASE copies of Gatsby—designed to be read about seven times—is over a million readings of the novel, as compared to Scribner’s sales of, tops, about 23,000 copies of the novel in 1925. Even if those ASE estimated readings are inflated, one of the things some of these World War II servicemen carried with them back home was an awakened interest in F. Scott Fitzgerald.

When I exhume it from its archival box, ASE #862 of The Great Gatsby looks to me like a thicker version of a child’s flip book. (The Diamond as Big as the Ritz, ASE #1043, will turn out to be bigger, more the size of a book of postcards.) The Great Gatsby is printed in yellow letters against a green background; a red band running across the bottom of the ASE assures readers that “This Is the Complete Book—Not a Digest.” Inside, the full text of Gatsby is printed on double columns with the thinnest of margins. At the end of the novel, there’s a little essay about Fitzgerald and his career that gives the wrong date for his death, 1941, but ends on a rousing (if grammatically confused) note: “Today, people are discovering Jay Gatsby and critics still shouting about it.” I check and see that orgastic on the final page has been misprinted, as it was in some other later editions of the novel, as the more salacious orgiastic. The real thrill to be found in this edition of Gatsby, however, lies on its back cover. There, some anonymous blurbist began a mission that would be carried on by millions of English teachers in classrooms around the world unto this very day: he (or she) enthusiastically assures the prospective readers of this ASE edition of The Great Gatsby that they won’t be bored. Instead, in the hands of the ASE blurbist, Gatsby becomes an action-packed crime story:

The Armed Services Edition of The Great Gatsby. (ERIC FRAZIER, REPRINTED COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISION)

Just as Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise immortalized college life in the America of the 1920s, so The Great Gatsby presented a deathless figure in the person of Jay Gatsby, one of the first, and certainly one of the greatest, of the “racketeers” in American fiction. Gatsby is a great and mysterious figure. The story of his life among the Long Island bootleggers and society people of well-remembered years is unequalled.22

I wonder how many GIs and sailors stuck with Gatsby after that pitch, redolent of bullets and booze? Nick’s elegiac opening words must have baffled more than a few of these guys. Then again, those overseas readers in uniform were something of a captive audience for Gatsby; as compared to your average overscheduled high-school student, I’d bet that, given the lack of alternatives, most of the soldiers who picked up Gatsby read the entire novel, cover to flimsy ASE cover.

The troops probably didn’t need any prodding to read the numerous mystery titles available as ASEs—everything from classic British tales of Sherlock Holmes and Dorothy Sayers to the courtroom dramas of Erle Stanley Gardner and the hard-boiled fiction of Raymond Chandler. I could use a Holmes or Perry Mason right now to help me figure out the lingering riddle of the ASE Gatsby: Why was Fitzgerald’s novel lifted out of its near-two-decades-old remaindered pile and chosen for the ASE program in the first place? According to the various accounts I’ve read, an unpaid advisory committee met twice a month to select the books, which came “from many sources.”23 Approximately thirty new titles were added each month. Consensus had to be reached about each selection, which was then presented to the army and navy for approval. (Censorship occasionally came into play when books were thought to be “political” or otherwise scandalous. Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage, for instance, was vetoed because it contained an attack on Mormons.)

In hopes of solving this whodunit, I’ll spend hours in the main reading room of the Library of Congress poring through old articles about the ASE program contained in musty copies of Publishers’ Weekly from the mid-1940s. Black-and-white photographs accompanying a 1943 article heralding the ASEs depict publishing eminences sitting around a gleaming wooden table on which stacks of paper are squarely aligned. Aside from one woman, all the participants are straight out of central casting: white men who look like they’re thinking serious thoughts about Literature. This was a time when publishing and academia were still waspy, inbred preserves. (I imagine the mangy Beat writers—Ginsberg, Kerouac, Corso—gathering in the shadows under similar tables in a few years’ time, overthrowing those neat piles of paper, the politeness of it all.) Another section of this extensive Publishers’ Weekly profile of the program lists the names of the members of the ASE selection committee: Mark Van Doren; Harry Hansen, literary editor of the New York World-Telegram; Amy Loveman of the Book-of-the-Month Club and the Saturday Review; Edward C. Aswell of Harper, Russell Doubleday; Jennie Flexner of the New York Public Library; and then, the only name that suggests a direct link to F. Scott Fitzgerald: Nicholas Wreden, president of the American Booksellers Association and manager of the Scribner’s bookstore on 597 Fifth Avenue.

Scribner’s. Max Perkins was still plugging away there in 1943. (In fact, he worked up until his sudden death in 1947 from an advanced case of pneumonia that he’d ignored.) Perkins had very reluctantly consented to be interviewed by Malcolm Cowley for a New Yorker profile that ran in two successive issues in April 1944. Entitled “Unshaken Friend,” it introduced the wider literary public to the role that this unassuming man who always “dressed in shabby and inconspicuous grays”24 had played in shaping the American literature of the twentieth century through Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Thomas Wolfe, among others. Scribner’s—through Perkins and, perhaps, through the intervention of bookstore manager Nicholas Wreden on the ASE selection committee—would forever remain F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “unshaken friend.”

Thinking of Perkins alive and working throughout the war years makes me wonder about Zelda. Would she have been aware of the reclamation efforts by Fitzgerald’s friends and admirers in the early years of the 1940s? Would she have known about the ASEs of The Great Gatsby and Diamond as Big as the Ritz? Zelda was living in Montgomery, Alabama, with her mother when Scott died. Apart from Scottie, of course, and Scott’s Princeton friend John Biggs, who became the executor of his estate, Zelda also had contact with Harold Ober, Max Perkins, and Edmund Wilson, as well as other longtime friends, like Gerald and Sara Murphy. She lived through World War II, going in and out of Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina. It’s an indicator of how shaky the Fitzgerald family finances were that Zelda sometimes bussed tables for money at the Richmond Hill Inn in West Asheville between stays at the hospital. In 1948, Zelda, housed in an upper room of the hospital awaiting the next day’s electroshock treatment, died in a fire set by a night supervisor who was said to be a recovered mental patient.25 The same Episcopalian minister, Raymond P. Black, who had so dismissively performed Scott’s funeral officiated at the burial of Zelda’s ashes at the Rockville Union Cemetery.

Rooting around for information about Zelda during World War II, I come across a reference to a letter she wrote in February of 1943. It’s preserved in something called the Noel F. Parrish papers at the Library of Congress, some fifty-eight containers of material. I’d never heard of Parrish, but it turns out that he was the white commander of the Tuskegee Army Airfield, responsible for training the Tuskegee Airmen. Parrish, according to testimonies I read, was hailed for his progressive racial views: he worked to improve life on the base, defusing tensions with local whites and arranging visits by celebrities like Lena Horne and Langston Hughes. Tuskegee was about thirty-five miles from Zelda’s parents’ home at 322 Sayre Street in Montgomery, and Parrish and Zelda somehow met. Judging by her letter, they shared a love of literature. Zelda starts off thanking Parrish for the loan of a book but quickly segues into a grand estimation of Scott’s writing against the backdrop of World Wars I and II:

The significance of social machination which colour Scott’s work always offer promise of another good time—as if just living might once again become a relevant estate.

Scott’s generation—and mine—made the adjustment from the Victorian age to the bitter gallantries of the last war, found a philosophy of tragic truncate exaltation to tide it over the heart-broken memories of men frozen in box cars and drowned in mud on the lost frontier of foreign countries. Now that age is tired resigned but not too philosophic. We await the end with a list too full of suicides and too fraught with tragedy to bring much hope to the current debacle.26

Zelda’s language is so interior, she might as well be talking to herself, though the phrase tragic truncate exaltation stays with me. She sounds exhausted and, sadly, beyond whatever lift the news of a burgeoning Fitzgerald Revival could give to her. As Scott wrote in a letter to Scottie the week before he died: “The insane are always mere guests on earth, eternal strangers carrying around broken decalogues that they cannot read.”27

Though they weren’t the very first paperbacks, the ASEs helped usher in the paperback revolution of the late 1940s and 1950s, so crucial to resurrecting and broadly repackaging Fitzgerald’s writing. (Cheap paper editions of books, such as the penny dreadfuls and railway-edition reprints of Victorian novels, had been around since the nineteenth century, but their quality—inside and out—was low.) In 1935, Penguin Books launched a line of mystery and literature titles in paper and sold them in Woolworth’s stores throughout Great Britain. As its name suggests, Pocket Books brought out the first pocket-size paperback books in the United States, in 1939, inaugurating its imprint with ten titles at twenty-five cents each; Avon Books came along in 1941, quickly followed by Popular Library and Dell.28 In 1946, Bantam chose The Great Gatsby as one of its first ten titles when it entered into the book market with paperbound editions. When the 1949 Alan Ladd movie of The Great Gatsby came out, Bantam added a beefcake dust jacket to this paperback, showing a bare-chested Alan Ladd standing by his swimming pool as Howard Da Silva’s Wilson points a gun at his back. Penguin, which had kicked off the paperback revolution, chose The Great Gatsby in 1950 as the first of its Fitzgerald titles.

Just how helpful were paperbacks to Gatsby’s fortunes? Bantam reprinted Gatsby five times between 1946 and 1954. A 1951 edition of the Bantam paperback includes this advice to readers on the first page: “You will understand, when you read this novel, why a great wave of popularity for Fitzgerald’s books is sweeping the entire country.”29 A Charles Scribner’s Sons royalty report to Scottie dated February 1, 1952, shows that from merely July to December of that year, Bantam sold 140,701 copies of The Great Gatsby.30

Of course, paperbacks weren’t the only new cultural commodities on the block in the late 1940s and 1950s: early television scavenged popular novels and plays for story material.31 Many of Fitzgerald’s novels and short stories got a new life on the small screen, among them The Last Tycoon (1949), “The Rich Boy” (1952), and The Great Gatsby (1958), all of which were produced for the Philco Television Playhouse series. The Last Tycoon (1951) and The Great Gatsby (1955) were part of the lineup of Robert Montgomery Presents, and CBS’s Playhouse 90 aired dramatic adaptations of those two novels in 1957 and 1958, respectively. DuMont Television produced “Babylon Revisited” in 1953.

Works of fiction began invoking Gatsby at least as early as 1930 with Nathanael West’s classic anti-Hollywood novel The Day of the Locust. West and Fitzgerald were mutual admirers. In his introduction to the 1934 Modern Library edition of The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald generously mentioned West’s Miss Lonelyhearts as an example of a first-rate novel by a promising younger writer; Fitzgerald also wrote a letter of recommendation for West, who had applied for a Guggenheim Fellowship. (He didn’t get it.) In one of those grotesque turns of literary history, the two men died within twenty-four hours of each other: West and his wife, Eileen McKenney (the inspiration for the Broadway play My Sister Eileen), were driving back from a Mexican vacation on December 22, 1940, when he ran a stop sign. The ensuing collision was fatal for them both. Most accounts of the accident say that West was upset upon hearing of the death of Fitzgerald the previous day. Fitzgerald had praised The Day of the Locust, which came out in 1939, but apparently didn’t see the darkly parodic echoes of Gatsby that I think are pretty apparent: the siren in Locust is named Faye Greener (Daisy Fay, green light, get it?); the “dreamer” in West’s novel also ends up drowning, this time around in a “sea” of fans at a Hollywood premiere.

Charles Jackson, author of the 1944 novel The Lost Weekend—about an alcoholic writer modeled, in part, on Fitzgerald—also fed the Fitzgerald Revival. Jackson worshipped Fitzgerald, to the point that he had had Fitzgerald’s nine books expensively bound in Moroccan leather and even impulsively called up Fitzgerald (whom he didn’t know) after reading Tender Is the Night. “Why don’t you write me a letter about it?” Fitzgerald reportedly said in an effort to cut the conversation short. “I think you’re a little tight right now.”32 In an arresting scene in The Lost Weekend, the main character, Don Birnam, presents a booze-fueled lecture to a room of imaginary students:

“He took down The Great Gatsby and ran his finger over the fine green binding. ‘There is no such thing,’ he said aloud, ‘as a flawless novel. But if there is, this is it.’ ”33

When Billy Wilder made The Lost Weekend into an Academy Award–winning film, in 1945, he said he had yet another alcoholic writer, Raymond Chandler, in mind as the model for Don Birnam. (Wilder and Chandler had worked together on the 1944 film Double Indemnity.) I like to think of Fitzgerald and Chandler “meeting” in The Lost Weekend, since it’s not clear whether they ever actually met in Hollywood.

Those are some of the highlights of the Fitzgerald Revival from the top down (the critics and academics) and bottom up (legions of soldiers reading their ASEs, the transfixed masses of new television viewers). In the decade before he died, Fitzgerald was forgotten by the general reader, written off by many of his peers. He was in the situation he imagined for Nick in The Great Gatsby: living beyond the golden moment in his own life. Now another such golden moment was happening for Fitzgerald, posthumously.

One sure confirmation that the revival was gathering force was the snorts of derision from the contrarians—a band alive and thriving today. In 1946, Robert Frost was in residence at Bread Loaf, the famed summer writers’ colony in Vermont. An interviewer asked Frost about the renewed interest in Gatsby and the poet shrugged: “Now they’re reviving F. Scott Fitzgerald. I finally got around to reading The Great Gatsby and I was disappointed.… We are ever so much nastier now than even Fitzgerald was then.”34 Five years later, the maverick literary critic Leslie Fiedler objected to all the Fitzgerald fuss in an essay with the deceptively dull title of “Some Notes on F. Scott Fitzgerald.” To Fiedler, Fitzgerald was a “fictionist with a ‘second-rate sensitive mind’ ”:

We are likely to overestimate his books in excessive repentance of the critical errors of the ’thirties—for having preferred Steinbeck or James T. Farrell for reasons we would no longer defend. Fitzgerald has come to seem more and more poignantly the girl we left behind—dead, to boot, before we returned to the old homestead, and therefore particularly amenable to sentimental idealization.35

The contrarians remind us that not everyone was (or is) smitten by his reading (or subsequent rereadings) of Fitzgerald. In advance of the premiere of the Baz Luhrmann film of The Great Gatsby in May 2013, New York magazine book critic Kathryn Schultz made a splash with her essay “Why I Despise The Great Gatsby.” Schultz declared: “I find Gatsby aesthetically overrated, psychologically vacant, and morally complacent; I think we kid ourselves about the lessons it contains. None of this would matter much to me if Gatsby were not also sacrosanct.” Schultz’s pan went viral because, these days, saying you “despise” Gatsby—the novel that is now so much part of the fabric of our American life—is like saying you “despise” cotton. (Despise, really? I understand when people tell me they were underwhelmed or even bored by Gatsby, especially on first reading, but hatred seems an extreme response to such a subtle novel.)

As the Fitzgerald Revival of the late 1940s and beyond was barreling through American classrooms, bookstores, libraries, and popular culture, some of Fitzgerald’s own descendants were a little slow to catch the fever. Eleanor Lanahan, the elder of Scottie’s two daughters, was born in 1948. In the illuminating biography that she later wrote about her mother, Scottie, Eleanor recalls her embarrassment when a guest at a dinner party addressed a remark to her about The Great Gatsby, which the eighteen-year-old had never read. Eleanor resolved to “sneak to the book stacks at Sarah Lawrence College”36 the following semester. Eleanor elaborated in an e-mail to me, written in the summer of 2013 during the Baz Luhrmann Gatsby madness:

My mother was always very low-key about her father, her heritage, his books.… She told me nothing about my grandparents until I was about eleven years old.… She didn’t say much about Gatsby as literature. Once my mother told me she thought Gatsby was popular on college curriculums because of its brevity.… Nobody in my family ever spoke of Gatsby as “The Great American Novel”—and “only” 20 years ago my father, who was a trustee of the Fitzgerald literary trusts—although my parents were long divorced, expressed his surprise that the book continued to be read, and turned into films, plays and ballets. Interest was sure to peak, he felt, and would soon.

Scottie Fitzgerald was crucial to fostering her father’s posthumous entry into the American canon. By refusing executor John Biggs’s advice that she sell off her father’s papers piecemeal and insisting instead that his manuscripts and letters be kept together, she preserved a treasure trove open to generations of scholars and interested general readers. Scottie seems to me, from afar, to be one of literary history’s most likable “daughters of.” Despite the fact that during the latter part of her childhood and throughout her adolescence her mother was emotionally erratic and frequently institutionalized and her father depressed and drinking, I’ve come across only one or two negative comments that she made about her parents. To be such a resolute “glass-half-full” kind of person, Scottie had to be adept at seeing only what she wanted to see, but one thing she never seems to have been in denial about was her father’s talent. In that low-key way her daughter Eleanor describes it, Scottie, even as a teenager, knew that her father’s writing was special. I say this because of the evidence of the letters: Scottie saved her father’s letters to her, even though they were often dictatorial and chiding.

But despite Scottie’s good instincts about her father’s writing, she didn’t know much of anything about his books or short stories as she was growing up. Fitzgerald himself seems responsible for this blackout. In a conversation with scholar Matthew J. Bruccoli that was recorded in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1977, Scottie recalled that she didn’t read her father’s work—with the possible exception of the short story “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button”—“until the summer I graduated from high school” (circa 1939). Scottie told Bruccoli that she thought her father “didn’t want me not to like them.” Instead, he read Dickens and Kipling aloud to her. Scottie told Bruccoli that her father also enthusiastically recommended Vanity Fair, the Oz books, the works of Jules Verne, and The Three Musketeers to her.

Bruccoli, Bruccoli, Bruccoli. This funny vegetable of a name pops up all over the place in Fitzgerald Land. (References to Bruccoli have already been liberally scattered through the earlier chapters of this book.) I was familiar with the name from my Scribner’s authorized edition of The Great Gatsby, which Matthew J. Bruccoli edited, as well as from my critical readings in American literature over the past few decades. In addition to Fitzgerald, his first love, Bruccoli was an authority on, among others, Hemingway, John O’Hara, Thomas Wolfe, Joseph Heller, and Ross Macdonald (who venerated The Great Gatsby and in 1966 wrote an excellent Lew Archer mystery novel based on it, Black Money). But it wasn’t until I began doing serious research on Gatsby that I grasped the scope of Matthew J. Bruccoli’s magnificent obsession with F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Every great writer deserves an ardent acolyte, a super-reader who will dedicate a career to generating biographies, critical editions, articles, and monographs. For Henry James, there was Leon Edel; Jane Austen, F. R. Leavis; James Joyce, Richard Ellmann. The Fitzgerald Revival, as I’ve said, was sparked by a determined reclamation effort on the part of Fitzgerald’s well-placed literary friends and admirers; it was given a timely boost by the intervention of the ASE editions and the paperback revolution. Scottie Fitzgerald also played a central role as the steward of her parents’—and particularly her father’s—literary and cultural memory. But the Fitzgerald Revival kicks it up a notch when the Bronx-born scholar with the difficult-to-pronounce last name enters the arena. (Bruccoli is pronounced “Brook-uhly.”) Though he always appeared in photographs dressed in jacket and tie, Bruccoli looked more like a gumshoe or a bouncer than a professor. His trademark crew cut and scowl, as well as his fondness for flashy sports cars, added to the tough-guy aura. Improbably, Bruccoli became Scottie Fitzgerald’s scholarly soul mate and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s most ardent champion.

Not everyone in the Fitzgerald community is a fan of the late Matthew J. Bruccoli (he died in 2008). As you’d expect with such a larger-than-life and, sometimes, abrasive character, he had his detractors. There are folks who say Bruccoli thought he was F. Scott Fitzgerald and who maintain that he made it difficult for other scholars to gain access to some Fitzgerald material. Bruccoli edited The Cambridge Edition of “The Great Gatsby,” which was published in 1991—the first volume in that series of the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald. But Bruccoli fell out with the Fitzgerald estate because, among other things, he wanted to change some of the language of Gatsby to accord with Fitzgerald’s later thoughts. Again, depending on whom you talk to, Bruccoli was either trying to be true to Fitzgerald’s intentions or trying to play Fitzgerald himself. Admire or disparage him, everyone who had dealings with Bruccoli agrees that he was a force to be reckoned with. That’s why I think I’ve “met” Matthew J. Bruccoli in the best possible way: through his writing.

When I entered graduate school in the late 1970s, there were more than a few characters like him around, people who lived and breathed their chosen subjects. As annoying, even offensive, as some of them could be, they did more than just adopt theoretical positions toward literature; they actually knew things. Bruccoli had an encyclopedic knowledge of all things Fitzgerald; more than for that, though, I admire him (at a safe distance) for the enthusiasm of his writing. Bruccoli—like Alfred Kazin, Edmund Wilson, and their fellow public intellectuals of the mid-twentieth century—wasn’t afraid to be subjective, to put his opinions and feelings into his criticism. I find one statement in particular that Bruccoli made about Fitzgerald endearing. He said that Fitzgerald knew he had created a masterpiece in The Great Gatsby because “geniuses know what they are doing or trying to do.”37 It’s no longer considered intellectually sophisticated to use words like masterpiece and genius. Sometimes, though, a work like Gatsby demands the risk of ridicule.

Bruccoli was interviewed many times about his love for Fitzgerald. He was good copy: a gravel-voiced professor who knew how to tell a story and didn’t pull his punches when it came to rating other writers and critics.38 The story Bruccoli told about how he came to fall in love with Fitzgerald is directly tied to Fitzgerald’s early infiltration into American popular culture. Bruccoli said he first discovered Fitzgerald in 1949, when he was a teenager riding in the back of his parents’ Dodge on a Sunday afternoon and listening to a radio dramatization of “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz.” Smitten, he went to his high-school library the next day to take out Fitzgerald’s short stories, only to be met by bewilderment from the school librarian. The Fitzgerald Revival hadn’t yet reached Bruccoli’s corner of the Bronx.

Undeterred, Bruccoli ferreted out Fitzgerald in other New York City libraries. (One later newspaper profile appropriately dubbed him “Bruccoli the Bulldog.”39) Some years later, he and his wife, Arlyn, would pay thirty-five dollars—in five-dollar installments—for a dust-jacketed first edition of The Great Gatsby. That volume, and the many, many other valuable Fitzgerald editions to follow, would become jewels in the crown of the Ernest F. Hollings Special Collections Library at the University of South Carolina, where Bruccoli was a distinguished member of the faculty from 1969 until his death, in 2008. That collection now has three first-edition Gatsbys, each worth well over a hundred thousand dollars. In 1994 (the last time anyone attempted an estimate), the Matthew J. and Arlyn Bruccoli Collection as a whole was valued conservatively at $1.2 million.

I think even his detractors would grant that Bruccoli’s story, like Gatsby’s, is primarily about love, not money. Bruccoli met and bonded with Scottie Fitzgerald at a charity auction in 1964, where he was trying to buy two Fitzgerald books. When he missed out on both, Scottie Fitzgerald—who’d donated the books and who observed his disappointment—bought a third Fitzgerald volume someone else had donated and presented it to Bruccoli. Years later, when she was dying, Scottie arranged for some of her father’s books to be sent to Bruccoli after her death. Bruccoli said, “She felt that she was letting me down by leaving.”40

That memory conveys a sense of the relationship that the scholar and the “daughter of” had. Their partnership stretched over two decades, during which time they collaborated on several books. When the shooting script for the 1974 film of The Great Gatsby was delivered to Scottie for approval, she and Bruccoli sat up together all night with a pot of coffee, reading it at her Georgetown home. Film enthusiasts will recall that Francis Ford Coppola wrote that script after an earlier script by Truman Capote was deemed, in Coppola’s words, “too loopy.”41 Coppola remembers that he had two or three weeks to write the script and that, though he had read Gatsby, he didn’t remember much of it. When he reread it for his assignment, Coppola was “shocked to find almost no dialogue between Gatsby and Daisy in the book.”42 (Coppola improvised dialogue drawn from Fitzgerald’s many rich girl–poor boy short stories.) For the premiere of that film in New York on March 27, 1974, Scottie invited the Bruccolis—as well as ninety cousins and friends, including the steadfast Judge John Biggs and his wife—to stay at the Waldorf-Astoria as her guests. After the screening, Paramount further whipped up Gatsby fever by hosting a banquet for two thousand guests in the Waldorf’s ballroom, decorated with three thousand white roses and two hundred and fifty potted plants.43

That lavish Gatsby adventure was preceded by a more curious excursion that Scottie and Matthew Bruccoli took together into one of the byways of the extended Fitzgerald Revival. In 1969, the bandleader Artie Shaw contacted Scottie about making a Broadway musical out of The Great Gatsby. Bruccoli accompanied Scottie to several meetings in hotels and restaurants. Bruccoli recalled that “at one of the restaurants… [Artie Shaw] decided to sing us the musical score. It was fairly cringe-making.”44 The musical was never made, but, oh, to have been a fly on that restaurant wall.

On his own, Bruccoli wrote or edited some sixty scholarly books, many of them on Fitzgerald or his Jazz Age compatriots like Ring Lardner, John O’Hara, and, of course, Hemingway. In 1981, he published Some Sort of Epic Grandeur, recognized by many scholars as the gold-standard biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald, although there’s a faction who think Arthur Mizener’s 1951 book The Far Side of Paradise is still the best. (If I had to choose only one, I’d vote for Bruccoli’s biography, because Mizener’s feels dated and a bit censored. For instance, presumably because Edouard Jozan was still alive, his name was changed in that section of the biography.) Bruccoli wielded so much weight at the University of South Carolina that whenever any significant Fitzgeraldiana came up for sale, he was usually able to convince the administration to raise the money for him to make a serious bid. In 1994, Bruccoli and Arlyn, a collector and scholar in her own right, partly donated, partly sold their own vast archive of Fitzgerald’s papers and belongings to the University of South Carolina.

That archive is what brings me to the home of the Gamecocks in the steamy midsummer of 2013. Maybe Bruccoli had restricted access to some Fitzgerald material in the past, but the archive doesn’t reflect any tendencies toward territoriality. Bruccoli said that anyone was welcome to use his collection as long as that person wasn’t wearing a baseball hat and his or her hands were clean. I show up bareheaded and scrubbed.

And wet. It’s raining in Columbia when I arrive. Indeed, it will rain so torrentially every afternoon for the next four days that, on my final morning on campus, my visit to the library will have to be canceled because the university loses power due to “weather.” The University of South Carolina was founded in 1801 and there are some lovely antebellum buildings around, but the daily monsoon creates “muddy swamps” and “prehistoric marshes” in the grass and pathways, rendering them as impassable as Nick’s “irregular lawn” on the fateful afternoon that Gatsby and Daisy are reunited. The fungal gloom of the campus is enhanced by the fact that I arrive between summer sessions, so the place is pretty deserted. All in all, ideal weather conditions for a few days’ deep immersion in the Bruccoli Collection.

Jeffrey Makala, the friendly and astute rare-books and special collections librarian who will be my guide, confirms my opinion that librarians, along with independent-bookstore owners and dedicated middle- and high-school teachers, are the most selfless guardians of literature on earth. I introduce myself with a lame joke about making sure that I didn’t wear a baseball hat. Jeffrey smiles politely and says that, in Bruccoli’s day, researchers also had to make sure they didn’t mention they were working on trendy topics like “theorizing Fitzgerald” or “Fitzgerald and gender.” Within five minutes of my arrival, Jeffrey leads me downstairs to the vault where the Fitzgerald treasures are kept. There, yet another by-product of my Catholic upbringing quickly surfaces: my excessive reverence for relics. I’m soon so overwhelmed by what Jeffrey is placing in my (clean) hands, that my most oft-repeated comment is “Wow!” (Professor Bruccoli, doubtless, would not have been impressed.) I hold, in succession, the collection’s three first editions, with dust jackets, of The Great Gatsby. Beautiful. The night sky on their dust jackets is a deeper greenish blue than paperback reproductions suggest. Jeffrey lifts more treasures off the immaculate shelving in the vault and begins handing them to me: the inscribed silver flask that Zelda gave to Scott in 1919; Fitzgerald’s walking stick; the copy of For Whom the Bell Tolls that Hemingway inscribed to Fitzgerald; Fitzgerald’s (unsigned!) copy of the Scribner’s contract for The Great Gatsby. Wow! Wow! Wow! I’m behaving like one of those notorious literary tourists, but there’s an undeniable thrill to holding the real thing in your hands. Besides, why should I feel self-conscious when Fitzgerald himself behaved like the consummately uncool culture vulture, forever kneeling before those writers and artists—Edith Wharton, James Joyce, Isadora Duncan—he worshipped?

Granted, there are also some lesser specimens of Fitzgeraldiana in the collection, examples of what Meyer Wolfshiem would have called tchotchkes stored elsewhere in the lower regions of the library. The following day, Jeffrey will lead me into another pristine storage area that houses the almost-complete collection of Armed Services Editions that Bruccoli began buying in 1959. (Ever on the lookout for a find in a secondhand bookstore, Jeffrey keeps a scribbled list in his wallet of the ASE titles the collection lacks.) High atop some beige metal shelves are two rattan end tables from Fitzgerald’s Baltimore days. On another nearby shelf sits a neatly boxed porcelain Gatsby Dollhouse from the 1970s, complete with figures of Daisy and Gatsby, as well as a Gatsby light-up roadster. “Pool not included,” Jeffrey quips.

On my second damp day in Columbia, after my initial dazzlement has gotten under control, Jeffrey and I have lunch together to talk some more about Professor Bruccoli and the collection. Jeffrey tells me about a Fitzgerald family sofa from the 1930s that Scottie Fitzgerald gave to Bruccoli. At the time, the Hollings Special Collections Library declined to accept the couch, so Professor Bruccoli ended up giving it to the residential college within the university. Jeffrey says the students there call the couch Zelda. On the way back from lunch, we walk over to that college to take a look at the new, reupholstered Zelda—the handiwork of prisoners at the state penitentiary—but that building is being renovated and the couch must be in storage somewhere. I miss out on sitting on Zelda, but I get a great consolation prize. When we arrive back at the library, Jeffrey unlocks an exhibition case. First, he hands me Fitzgerald’s typewriter eraser. (I’m a bit confused by this relic since Fitzgerald didn’t type, but Jeffrey tells me the eraser was a gift from Scottie, so her father must have used it.) Much more poignant is the second object Jeffrey takes out of the exhibition case: a battered brown leather briefcase that Fitzgerald used in Hollywood. Fitzgerald’s name is engraved in gold letters on the front of the briefcase, as is his address: 597 Fifth Avenue. That’s the address of the Charles Scribner’s Sons Building, Fitzgerald’s only permanent home.

The excitement of these unexpected hands-on encounters aside, I’ve come prepared for this research trip with my own wish list of things I want to study, and near the top is Sylvia Plath’s copy of The Great Gatsby that she read—and marked up—as an undergrad at Smith College. The young Plath read the 1949 Grosset and Dunlap edition, which looks a lot like my cherished antique blue editions of the Nancy Drew books. (Fittingly, given their common love of fast roadsters, Gatsby and Nancy briefly shared a publisher.) How did the undergraduate Plath read Fitzgerald? The answer is studiously. Plath underlines words and sentences on practically every page of her Gatsby. Most of the underlinings have something to do with color symbolism. (Plath’s professor must have been of the breed of scholarly symbol hunters.) There are lines under Myrtle’s sister’s “sticky bob of red hair,” George Wilson’s “light blue eyes,” and Myrtle’s “brown figured dress.” Indeed, a lot of the comments and underlinings convey the impression of a good student taking down a professor’s lecture notes. In the margin of that scene in the final chapter where Tom and Nick meet again, Plath has written in blocky ink letters: TOM RESPONSIBLE FOR GATSBY’S DEATH. Other notes fall into the category of commentary that a student makes when she or he is trying to be sophisticated: Plath writes l’ennui next to the paragraph in chapter 1 where Daisy tosses off her “beautiful fool” speech. But a few of the comments have the feel of a sensitive reader—a poet in the making—savoring the language. On page 103 of her edition, Plath underlines this description of Daisy: “A damp streak of hair lay like a dash of blue paint across her cheek.” And earlier in the novel, when Jordan declares that she likes “big parties because they’re so intimate,” Plath prints good next to the passage. Just as you’d expect, Plath underlines the last line of The Great Gatsby.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s briefcase. (MATTHEW J. & ARLYN BRUCCOLI COLLECTION OF F. SCOTT FITZGERALD, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA LIBRARIES)

As I said, I came to the Hollings Special Collections Library with a list of must-see items, but on that first trip down into the vault, Jeffrey generously shows me a treasure that I didn’t even know existed. Many serious readers of The Great Gatsby are also unaware of this find, even though, like Poe’s purloined letter, it’s lying out in the open, prominently listed on the library’s website for the Bruccoli Collection and mentioned by Bruccoli in an afterword he wrote accompanying the library’s publication of a facsimile edition of the Trimalchio galleys in 2000.

This treasure in plain sight, like the prize in Poe’s story, is a letter. It’s written in Fitzgerald’s hand and the heading on the top right corner reads Great Neck, L.I. It’s addressed to a Mr. Baldwin, who Jeffrey tells me was Charles Crittenden Baldwin, a journalist who wrote a book called The Men Who Make Our Novels, published in 1924. Fitzgerald’s letter, folded in three places and marked by cigarette burns on the right margin, seems to be a response to the general questionnaire that Baldwin sent out to novelists when he was working on that book.

The letter was tipped into a first edition of Tales of the Jazz Age that the Hollings Special Collections Library bought in the 1990s. (Tipped in is book collectors’ lingo for an object, almost always a piece of paper, that’s attached, usually by glue, to a page of a book by its corners.) By the 1990s, exhaustive collections of Fitzgerald’s letters had already been published, so this letter was left out in the cold. In it, Fitzgerald is begging off writing “very full” answers to interview questions because “I’m sailing for Europe in two days and at my wit’s end for time.” That internal reference puts the date of this letter sometime in late April of 1924.

After Fitzgerald, ever the people pleaser, goes ahead and gives Baldwin some basic biographical facts of his life and recommends that Baldwin read a Smart Set profile of him that was published that spring, the revelation here comes in the third paragraph of the letter:

“My third novel (unpublished) is just finished.”

Just finished? Did I read that right? It’s never been clear how much of The Great Gatsby Fitzgerald wrote in that unheated room above the garage on Gateway Drive. If he’s telling the truth here (and why would he be lying?), then a completed draft of Gatsby sailed over to Europe with Scott, Zelda, and Scottie on the SS Minnewaska in the spring of 1924. That version of Gatsby, Bruccoli logically speculates, would be the first version, the one with the omniscient narrator whom Fitzgerald wisely rejected in favor of Nick. What’s exciting about this letter is that it takes the writing of the first draft of Gatsby back to the spring, rather than the summer, of 1924. This might not be breaking news to most of the world, but since the composition history of Fitzgerald’s masterpiece is so convoluted and fragmentary (recall that missing typescript of the first draft), any information is precious. But what’s even more remarkable is that, as the opening sentence of that third paragraph in his letter to Mr. Baldwin goes on, Fitzgerald tries to define his new novel. The sentence reads: “My third novel (unpublished) is just finished + quite different from my other two in that it is an attempt at…” Agh! What is that word?

The mystery word that Fitzgerald wrote in fountain pen in his mostly legible script falls on one of the letter folds. The word starts with an f and it could be form or force or farce. So, here we have F. Scott Fitzgerald defining in one word the essence of what may be the greatest American novel of all time, and the word is indecipherable. Terrific—a postmodern non-ending to this treasure hunt. I call upon Jeffrey for help and he obligingly comes from his office to peer at the letter in the rare-books reading room. Jeffrey votes for farce, which I like, because the comic nature of The Great Gatsby is so often overlooked. In his afterword to the Trimalchio facsimile, Bruccoli printed a typescript of the letter and used the word form. Weeks later, when I take a photocopy of the letter to Princeton, Don C. Skemer, who hadn’t seen it before, also votes for form. Form is the most logical choice given what we know about Fitzgerald’s focus on Gatsby’s structure. Still later, I e-mail a scanned copy of the letter to Scott Shepherd, the brilliant actor who played Nick Carraway—and memorized the entire text of The Great Gatsby—in the Elevator Repair Service’s production of Gatz. Shepherd, who’s thoroughly immersed in Gatsby and Fitzgerald—votes for form as well. Farce, form, force—you decide for yourself. Here’s a facsimile of the letter, which goes on to talk about the novel that will become The Great Gatsby in the context of modern American fiction.

On my last day at the Hollings Special Collections Library, the day before the power outage, I request to see something precious and personal. Forget literary tourism, I’m way over the line now and into literary voyeurism. The rare-book staffer brings out three photo albums, the kind with the black paper where, in olden days, people pasted in their black-and-white photos. Scott and Zelda put together these three albums; they span the years 1924 to 1931. Some of these photos I’ve seen before in a wonderful book that Scottie Fitzgerald and Matthew J. Bruccoli, along with editor Joan P. Kerr, first published in 1974, called The Romantic Egoists, which is also the title written on the third album: “The Romantic Egoists: Our Fourth Trip Abroad 3/1929–9/1931 Europe, Africa, etc.” The paper in these fragile albums is crumbling, but the images are alive because they’re out of focus, silly, and sometimes even unflattering. (Zelda and Scottie look fat in a few that are shot at bad angles.) On the first page of the first album is the most vibrant picture I’ve ever seen of Zelda; it’s blurry because she’s moving, mugging for the camera with her pointed fingers holding up her chin. Zelda, to me, often looks uncomfortable in photos, but this one is charming. By the third album, there are snapshots of “A Costume Ball” at Prangins, the Swiss mental clinic where Zelda was treated: Zelda is dressed as a lampshade and her psychiatrist, Dr. Forel, poses as a caveman. In between, the Fitzgeralds commit the forgivable crime of most new parents with a camera: they take way too many photos of baby Scottie. True to form, right before a picture of Scott holding Scottie over waves breaking on a beach, Scott has written (and misspelled) Rivierra. It’s the Riviera in 1924, the summer of The Great Gatsby. These three albums restore messy humanity back to the legendary Fitzgeralds. Scott is a playful dad and Zelda has been transformed from the jokey-if-affectionate name of a couch that art students sit on to an all-too-human person.