Chapter 12. How to Recruit

From a recruiting perspective, the best engineering manager I’ve worked with established her reputation with two hires. It went like this:

ME: “We need to build an iOS team, and while we have talented engineers, we don’t have time to train the current team on iOS. It’ll be faster to hire.”

HER: “Great, who should we hire?”

ME: “Here’s the perfect profile. We’ll never get him, but he’s an incredible, well-known iOS engineer who is not only productive but also a phenomenal teacher. He’d be a perfect seed for the team. We need an engineer like him.”

HER: “Why not hire him?”

ME: “You’ll never get him. Everyone is throwing everything at him.”

Three months later, the long-shot hire that I thought we had no chance at getting signed an offer letter. Two months later, same story. I mentioned an unattainable hire, which was followed promptly by the hiring of that specific engineer.

You probably think there was some trick here. You may think we threw huge amounts of money at these engineers—we didn’t. Standard compensation packages. You may think we promised them an impossibly cool role—we didn’t. The offer was to build the first version of an iOS application with a talented group of engineers.

There is no trick other than carving out time every single day to do the job of recruiting.

First Rule of Recruiting: Give It 50%

Let’s start with the rule. For every open job on your team, you need to spend one hour a day per req on recruiting-related activities. Cap that investment at 50% of your time. No open reqs? There’s still important and ongoing work you need to do on a regular basis that I’ll describe later.

Take a minute to digest that prior paragraph, because it might be a shock to many engineering managers out there. Seriously, 50% of my time? Yup. But we have a fully functional and talented recruiting organization. That’s super and will make your life better, but devoting 50% of your time to recruiting still stands. Why? I’m glad you asked.

On the list of work you can do to build and maintain a healthy and productive engineering team, the work involved in discovering, recruiting, selling, and hiring the humans for your team is quite likely the most important you can do. The humans on your team not only are responsible for all the work the team does but also are the heartbeat of the culture. We spend a lot of time talking about culture in high technology, but the simple fact is that culture is built and cared for by the humans who do the work. Your ability to shape the culture is a function of your ability to hire a diverse set of humans who are going to add to that culture.

Let’s dive into this in more detail.

A Recruiting Primer

A good way to think about your recruiting work is to delve into the stages of the recruiting process itself. Figure 12-1 is a snapshot.

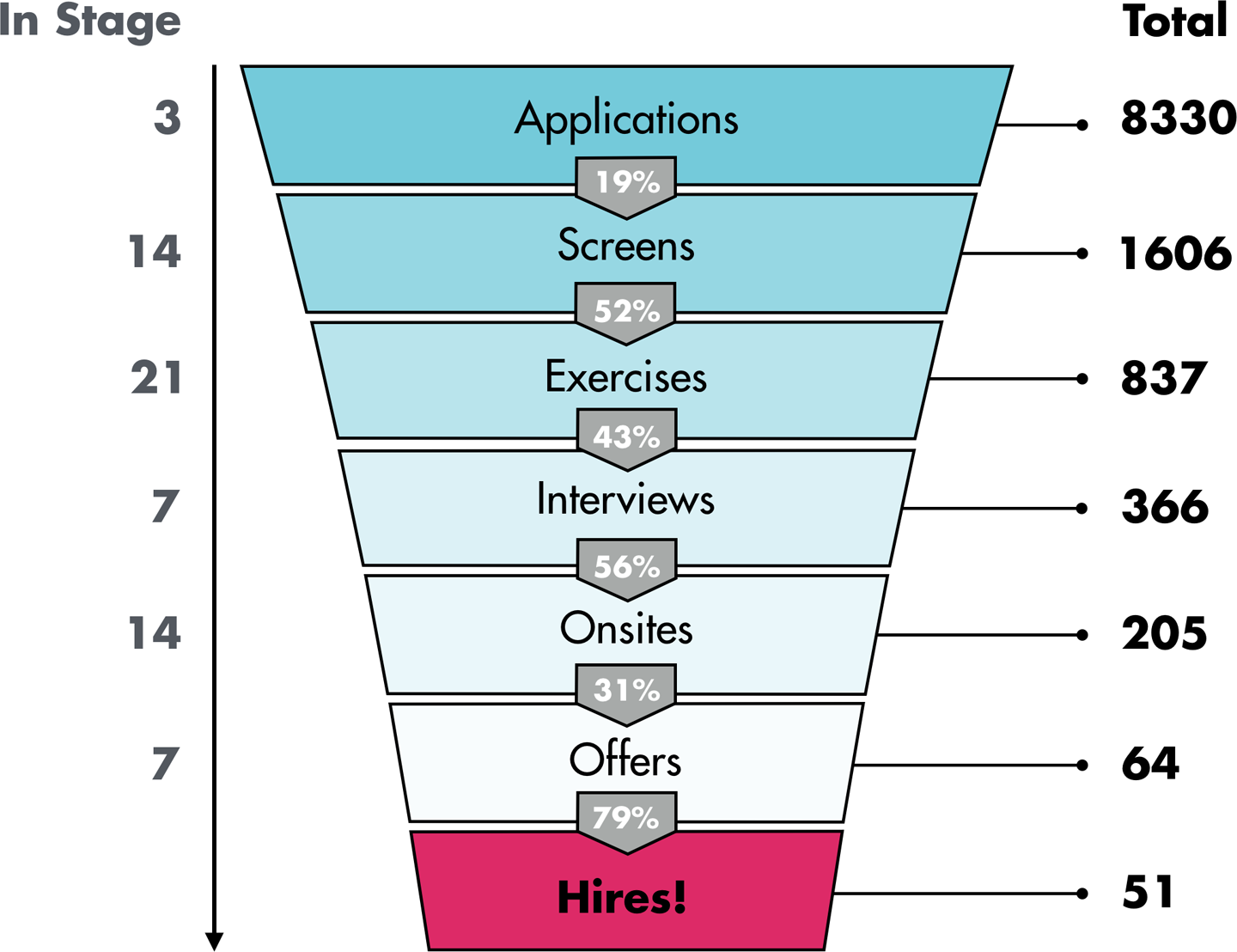

This is the hypothetical funnel chart for The Rands Software Consortium, and we’re hiring!1 I love funnel charts because they help frame multiple lenses of information in a single digestible view. The stages here are:

- Applications

- Applied for a role or were sourced by an internal or external party.

- Screens

- Made it past a first-round screening process.

- Qualifies

- Made it through a more critical screening process. Think coding challenge or technical phone screen designed to gather more signal.

- Interviews

- Entered the formal interview process.

- Onsites

- In the building for an interview.

- Offers

- Received an offer.

- Hires

- Accepted their offer.

Figure 12-1. Typical recruiting process, shown via a funnel chart

This fake graph represents a period of roughly six months. The “In Stage” number shows you how long on average a candidate spends in each stage in days. The gray percent numbers down the middle show you what percentage of candidates make it through a stage, and the “Total” number on the right shows you the total number of candidates per stage in the period in question.

Before we talk about where you should be spending 50% of your time, you first need to make sure you have two agreements in place with your recruiting team:

-

Agreement on the stages in your pipeline. The fake chart shown here is just one example; your flow might be different. What are the different stages? How does a candidate enter and exit a specific stage?

-

With #1 defined, you now need to agree to make it ridiculously easy to access this information.2

With all this data in place and the process running smoothly, you can learn about the efficiency of the different parts of your recruiting process and you can ask informed questions. Where are candidates spending the most time, and why? We gather the most signal at the coding exercise and the interview—shouldn’t those pass percentages be lower? How long is a candidate spending in each part of the process? Is that the experience we want them to have?

This chapter assumes you have a fully functional and talented recruiting team. These humans are essential for you to effectively do your part of the recruiting gig. Part of their job is to provide a clear and consistent perspective on the health of the entire recruiting funnel, as well as the status of any candidate in any stage in the pipeline. This partnership and this data will enable you to better understand where to invest your time.

Discover, Understand, and Delight

This chapter is not about the traditional recruiting pipeline and the familiar work you’re already doing. It’s about the work of recruiting you are neglecting. Let’s call this the engineering recruiting pipeline—it’s a pipeline built right on top of the funnel I described in the previous section. The different states in the engineering recruiting pipeline are based not on how we measure candidate progress, but on the evolving mindset of the candidate traversing the process. There are three states I consider as part of this unique pipeline: Discover, Understand, and Delight.

Discover

Discover, first, is the state of mind of any qualified candidate who does not yet know about the opportunity on your team and at your company. It is your job to find these humans and help them discover the desire to work with you at your company.

In recruiting parlance, those who find these candidates are sourcers. Their job is to look at your job description and identify humans who fit the bill. Sourcers cast their nets very wide and fill the top of the funnel with as many qualified candidates as possible. Sourcing is also your job during Discovery, but your time can be more focused because you have intimate knowledge of the gig. More importantly, you have likely worked directly with humans who you know can do the job. You can operationalize this fact by building The Must List.

The Must List

Make a list of each and every person you’ve worked with who you want to work with again. You must work with them again. Fire up a blank spreadsheet and start typing, because you’re going to want to capture a bunch of different data, and as the list grows, you’re going to want to slice and dice it in different ways.

List every person. Doesn’t matter if they’re an engineer or not. Keep typing. Doesn’t matter if they’re available or not. Write down their name, their current company, their current role, and why they’re on the list. Done? Put it away for a day and then come back. You missed important humans.

There are two use cases for The Must List. First, whenever a new gig opens up on my team, I fire up the List and see if there is anyone on it who might fit the bill. Then I send them a friendly note. Hi. How are you? Got a gig and I must work with you again. Coffee? More often than not, if we haven’t spoken recently, this human and I will get coffee regardless of their interest in the role because these are dear friends. Much more often than not, they are happy in their current gigs. Sometimes they’ll know folks who might fit the bill. Rarely, very rarely, they’ll come in for an interview. When coffee is done, I update the remaining columns in the spreadsheet: last contacted date, current status, next steps, and notes that capture their current context.

The second use case for The Must List is my monthly review. Every month or so, whether or not I have a relevant open gig on my team, I review the list and see whom I have not spoken with in the last 90 days. Time for an email? Okay: Hi. How are you? Coffee? Again, they’re rarely interested in switching gigs, but if they happen to be looking, I will move mountains to work with them again.

Return on time invested in the Discover state is going to feel a lot lower than in the forthcoming Understand and Delight states because it’s hard to measure progress. There are currently 42 humans on my Must List, and if I get one of them in the building a year, I’m giddy. However, these are my people and the time spent investing in this network almost always pays unexpected dividends in ways that have nothing to do with whether I can hire them. These are my people, and they know other people who might fit the gig or whom I should simply meet. They observe the world in interesting ways, and I want to hear those observations.

In Discovery, you are making targeted strategic investments in your network. The reason these folks are on your Must List is that you have seen with your own eyes the work they can do. You built a bond with these humans in a prior life, and these small investments of your time strengthen and reaffirm that bond. The value of this network is a function of the number and the strength of these connections.

Understand

On to the Understand state. A candidate has passed through the very crowded top of the funnel and has reached the evaluation portion. If you look at the hypothetical funnel numbers in Figure 12-1, this candidate is statistically unlikely to make it to the Offer stage. But regardless of whether they end up getting an offer or not, your job is to Understand.

The recruiting focus here is, “Do they have the necessary skills?” The interview process is designed to gather this information from the candidate. Your focus during Understanding is to again consider the candidate’s mindset. While they are getting peppered with questions about their skills and qualifications, they are also wondering, “Who is this engineering team?” “What do they value?” and “Where are they headed?”

Homework. Step away from your digital device this moment and ask a random engineer who is a part of your interview loops those three questions. Done? Now do it with another engineer. How do the answers compare? Is it the same narrative? Is it a compelling narrative?

The explanation of an engineering team’s culture is usually left to happenstance—the last few minutes of an interview, where you ask the candidate, “Do you have any questions for me?” This lazy question is cast out with the hope that the candidate responds with a softball like, “What’s it like to work here?” You respond with your well-practiced recital of “I love it here!” and “We’re solving hard problems!” which sounds about as interesting as it reads.

Your responsibility is to make sure the candidates understand your mission, culture, and values.3 While they will organically pick up some of this during interviews, you need to make sure it’s one person’s responsibility to clearly tell the engineering story. This is not an interview; the point is to clearly explain the shape of the place where they might work. And—bonus points—you are going to organically learn about them during the discussion of the character of your company.

There are two scenarios for a candidate passing through the Understand state. Scenario A: they receive an offer, and the time spent in Understanding paves the way to a rich offer conversation and allows them to hit the ground running when they arrive. Scenario B: they don’t get an offer, but they leave with a clear understanding of you, the character of your team, and your mission. Recruiters call the time spent interviewing “the candidate experience,” and I would suggest that whether they get an offer or not, Understanding is the cornerstone of an exceptional candidate experience.

Delight

We’ve reached the Delight state. Congratulations! You’re making an offer to an engineer. Going back and looking at those funnel ratios, you can see this is a statistically unlikely event. Let’s not screw it up, okay?

New managers often erroneously think when making an offer, “We’ve made a hire!” Experienced managers and recruiters know, “They’re not here until they are sitting in that chair.” If you and your recruiting team have done your work, the presentation of the offer is a formality because you already know the candidate’s life situation and goals. Offer construction, presentation, and negotiation is a topic for a whole other chapter, but it’s a clear sign that you missed critical information somewhere in the candidate experience if the negotiation process is unexpectedly laborious or littered with surprises.

They accept! Hooray! We’re still not done because they are still not sitting in that chair. Let’s welcome them. Let’s Delight them.

The nightmare scenario is a candidate declining an offer they already accepted. I think it’s professionally bad form, but it happens more often than you’d expect. Put yourself back in their shoes: they likely have an existing gig where everyone knows their name and they know where the good coffee lives. Even after a phone screen, an at-home coding exercise, a day-long round of interviews, two more phone calls, and assorted emails, you and your engineering team remain an unknown quantity. In the middle of the night, when the demons of doubt show up, you represent an uncertain future—and your job during Delight is to help them imagine their future with you.

Reflecting on my experience in this state, I think of how I act after I’ve accepted an offer. After the initial high of receiving and accepting the offer passes, what do I do? I reread the offer letter. I review the benefits. I go to the company website and I examine every word. What am I looking for? Why am I continuing to research? I’m vetting my decision.

The offer letter is an important document. It contains the definitive details of compensation and benefits, and these are important facts—but during this critical time of consideration, I want these future coworkers delighted with a Real Offer Letter.

I send the Real Offer Letter a week before the start date. I write a note each time that captures the following:

-

My current observations of the company, the team, and our collective challenges.

-

The first three large projects I expect the new hire to work on, why I think these projects are important, and why I think the new hire is uniquely qualified to work on them.

-

The growth path for the new hire, explained as best I can.

Nothing in this letter should be news. In fact, if there are any surprises in it, there was a screw-up somewhere earlier in the funnel. The purpose of this letter is to acknowledge that we are done with the business of hiring, and now we’re in the business of building.

During the post-offer-acceptance time, most companies send a note…a gift. I’ve received (and appreciated) flowers, a terrarium, and brief handwritten notes. Thoughtful gifts, but small thoughts. At a time when a new hire is deeply considering a change in their career, I want them chewing on the big thoughts. I want them to understand the humans they are joining and their mission. I want them to concretely understand what they will be working on, and I want them to understand the potential upside this new gig represents for their career.

Circling Back to 50% of Your Time

The work of recruiting is a shared responsibility. Yes, you can be a successful hiring manager devoting less than 50% of your time to it. Yes, all of the funnel work can be completed by a recruiter; many of my best recruiting moves came from watching and working with talented recruiters.

The situation I want to avoid is a hiring manager who delegates the entire recruiting process to their fully functional and talented recruiting team. There are critical leadership skills you need to learn and refine during the Discovery, Understanding, and Delight stages. In Discovery, it’s understanding the power of persistent serendipitous networking. In Understanding, it’s understanding how to tell the tale of your company as well as being able to understand the tale of the candidate. Finally, in Delight, it’s the ability to discern the best way to delight this candidate at a time when their worry and risk aversion are the strongest.

Recruiting and engineering must have a symbolic force multiplication relationship because the work they do together—the work of building a healthy and productive team—defines the success of your team and your company. That’s worth your time.

1 Not really. This is fake data, but it’s fake data based on experience. I’m making a couple of assumptions regarding this fake company. It’s got around five hundred employees. It’s in hyper-growth, which means it has a hundred plus open reqs. Your company or team is likely in a different stage of growth, but much of the strategy of this piece still applies.

2 This is usually where this process comes crumbling down, because you’re busy building the product and recruiting is busy recruiting, and providing ridiculously easy-to-access recruiting information requires a rigorous process supported by flexible tools. My advice if you’re building this for the first time is to assign a couple of engineers to this project for a year.

3 Yes, this means you’ve defined your mission, culture, and values and everyone agrees with these definitions.