CHAPTER 10

THE QUALITY OF US HEALTHCARE

Walter went to the doctor to find out why he sometimes had a burning sensation in his lips and mouth after eating. His doctor recommended some tests to help diagnose the problem. One involved endoscopy, a procedure used to examine the upper gastrointestinal tract with a small camera attached to a flexible scope that goes down the throat. However, the physician used a scope that was too large and tore a small hole in Walter’s esophagus, which was already constricted. Walter ended up in intensive care for ten days until his wound healed. During his stay, Walter’s physicians discovered that the cause of the burning sensation was oral allergy syndrome, caused by allergies to foods or even pollen. Although he received the right diagnosis in the end, his endoscopy and certainly the hole in his esophagus could have been avoided.

Walter’s story is not more or less important than any of the many stories related to patient safety and quality healthcare. Although Walter recovered from his torn esophagus, others are not so lucky. It is not uncommon for medical or surgical errors to cause death or significant impairment.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

Define healthcare quality from several perspectives.

Define healthcare quality from several perspectives.

Be familiar with current healthcare quality initiatives.

Be familiar with current healthcare quality initiatives.

List the different types of sentinel events.

List the different types of sentinel events.

Recognize key quality improvement tools.

Recognize key quality improvement tools.

Understand how power relationships effect healthcare quality.

Understand how power relationships effect healthcare quality.

DEFINING QUALITY

Healthcare quality is a broad concept that encompasses factors such as value, efficacy, reliability, and outcomes (Godfrey 2012). The Institute of Medicine defined healthcare quality three decades ago as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (Lohr 1990). This definition, however, does not explain how the different stakeholders in the healthcare industry view quality.

Some see quality as clinical outcomes, and others view it as service outcomes. For example, healthcare managers and policy experts might use data, metrics, and benchmarks to analyze clinical quality. They might ask, for instance, how many children have been vaccinated, or they might compare surgeons based on their surgical successes and failures, along with their techniques or equipment used. Another quality measure used by government is the number of patients who are readmitted to a hospital for care within a certain number of days or weeks.

Patients perceive healthcare quality as the quality of the services and facilities. Patients can easily judge the cleanliness of the hospital rooms, the friendliness of the nurses, the tastiness of the food, the availability of parking, how well their care is coordinated, the length of wait times, inclusion in decision-making, and whether their needs were met. These and other factors contribute to patients’ perceptions of their experience and the quality of their care. Patients believe that they have received quality care when the following expectations are met (Flavin 2018):

They feel understood.

They feel understood.

Their appointments are convenient.

Their appointments are convenient.

Their care is integrated.

Their care is integrated.

The facility maintains a calm atmosphere.

The facility maintains a calm atmosphere.

Wait times are short.

Wait times are short.

They understand what is happening and receive clear instructions.

They understand what is happening and receive clear instructions.

They feel sense of relationship with their providers.

They feel sense of relationship with their providers.

CLINICAL QUALITY

Clinical quality refers to the quality of the treatment that a patient receives. The Institute of Medicine defines six domains or properties of healthcare quality (AHRQ 2018):

- Effectiveness suggests the use of scientific evidence in the use of certain procedures and in achieving positive outcomes.

- Efficiency is the right amount of care for the best outcomes.

- Equity is providing equal care to all individuals.

- Patient centeredness means involving patients in decisions, meeting their needs, and educating them on the processes taking place.

- Safety is the idea of doing no harm or reducing potential harm.

- Timeliness means that individuals receive care as they need it.

However, physicians do not always agree on how policy experts should define and measure clinical quality. Some physicians argue that patients’ outcomes are hard to compare, as individuals are very different from one another (Godfrey 2012). Some patients have more severe conditions. Some comply with the instructions they are given by their physicians or other healthcare providers, while others do not. Moreover, those with insurance or higher incomes may have access to better care than those who lack insurance or have lower incomes.

One way to measure clinical quality is to compare the expected health benefits of a particular intervention or procedure to its expected health risks. Some argue that poor clinical quality may occur when patients receive too much care (e.g., unnecessary testing, too many different drugs, risky procedures), too little care, or the wrong kinds of care (Schuster, McGlynn, and Brook 2005).

A number of data sources seek to demonstrate healthcare quality. For example, the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) reports survey results from a sample of 184 million individuals enrolled in health insurance plans. These data provide measures across six domains: effectiveness of care, access to and availability of care, experience of care, utilization, health plan descriptive information, and measures collected using electronic clinical data systems. Results of the HEDIS survey are used to create “report cards” for health plans, healthcare providers, and healthcare organizations (NCQA 2020).

Another report of healthcare quality comes from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in the form of clinical quality measures (CQMs), which include patient and family engagement, patient safety, care coordination, population/public health, efficient use of healthcare resources, and clinical process/effectiveness (CMS 2020a). The CQM process is an ongoing system for measuring a variety of factors related to quality. Experts or “contractors” define the topics of measurement, gather data, create panels of experts, obtain public comments, test hypotheses, and report results. The reported results relate to all phases of healthcare, including postacute care, home health, hospital quality, nursing homes, physicians, and even specific diseases (CMS 2019b).

SIDE EFFECTS CAUSE QUALITY FAILURE

SIDE EFFECTS CAUSE QUALITY FAILURE

Lewis Blackman was born with pectus excavatum—a crease in his chest cavity—a condition that occurs in 1 in 500 people. For many years, experts considered pectus excavatum merely a cosmetic issue, but more recent studies have suggested that it could cause respiratory problems. When Lewis was 15 years old, he and his parents were told that surgery could correct the condition, so they decided to move forward with it.

Following the surgery, Lewis showed signs of distress: He was not producing urine, his temperature dropped significantly, his pulse was rapid, his skin grew pale, and he was in tremendous pain. Nurses and inexperienced physicians failed to recognize the signs that he was having an adverse reaction to a painkiller. They also failed to respond to his mother’s request that he be seen by a senior or attending physician.

Within four days of his surgery, Lewis died. The painkiller given to him had caused a perforated ulcer. His abdomen filled with three liters of blood and fluid—most of the blood in Lewis’s body. Those who reviewed his case suggested that a routine blood test would have shown that Lewis was bleeding internally.

In the end, Lewis’s parents tried to speak with the clinicians and administrators of the hospital where the surgery had been performed to share their ideas about how better communication with patients’ families might prevent similar events. Their requests were not granted. The hospital reported that physicians, nurses, and other hospital officials were working together to make changes to procedures and protocols so that such a case does not happen again (Monk 2002).

The surgeon and Lewis’s parents had different views of the quality issue that caused Lewis’s death. From the parents’ point of view, if the nurse or resident physician simply would have responded to their request to consult with a senior physician, Lewis’s death may have been prevented. From the surgeon’s point of view, this was a “one in a zillion case” (Monk 2002), because the blood from a bleeding ulcer like Lewis’s normally passes into the gastrointestinal tract, where it is vomited or passed through the colon. Blood pooling in the abdomen was something the surgeon had never seen in another patient.

PATIENT PERCEPTIONS OF QUALITY

Patients and their families have a different perspective on healthcare quality. Patients often forgive disappointing clinical outcomes if they have had a positive clinical experience or received excellent service (Godfrey 2012). The Institute of Medicine recommends considering the consumer perspective by measuring key aspects of quality such as staying healthy, getting better, living with an illness or disability, and coping with the end of life (AHRQ 2018).

One patient-focused report card on quality is the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS), which was first compiled in 1995. Healthcare providers today pay close attention to the results of this national report. CAHPS surveys focus on healthcare consumers’ views of their healthcare experiences. Consumers rate areas such as the communication skills of their providers and the ease of accessing healthcare services (AHRQ 2020).

Another quality report that is specific to hospitals is the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). Exhibit 10.1 lists some of the questions that this survey asks. As can be seen, the survey questions deal almost exclusively with service quality and patient satisfaction.

EXHIBIT 10.1 Selected Questions from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems

Details

The details of survey topics and related questions are as follows:

How often did nurses communicate well with patients?

- During this hospital stay . . .

- How often did nurses treat you with courtesy and respect?

- How often did nurses listen carefully to you?

- How often did nurses explain things in a way you could understand?

How often did doctors communicate well with patients?

- During this hospital stay . . .

- How often did doctors treat you with courtesy and respect?

- How often did doctors listen carefully to you?

- How often did doctors explain things in a way you could understand?

How often did patients receive help quickly from hospital staff?

- During this hospital stay . . .

- How often did you get help as soon as you wanted after you pressed the call button?

- How often did you get help in getting to the bathroom or in using a bedpan as soon as you wanted?

How often did staff explain about medicines before giving them to patients?

- Before giving you any new medicine . . .

- How often did hospital staff tell you what the medicine was for?

- How often did hospital staff describe possible side effects in a way you could understand?

How often were the patients’ rooms and bathrooms kept clean

- During this hospital stay . . .

- How often were your room and bathroom kept clean?

How often was the area around patients’ rooms kept quiet at night?

- During this hospital stay . . .

- How often was the area around your room quiet at night?

Were patients given information about what to do during their recovery at home?

- During this hospital stay . . .

- Did hospital staff talk with you about whether you would have the help you needed when you left the hospital?

- Did you get information in writing about what symptoms or health problems to look out for after you left the hospital?

How well did patients understand the type of care they would need after leaving the hospital?

- During this hospital stay . . .

- Did hospital staff consider your healthcare options and wishes when deciding what kind of care you would need after leaving the hospital?

- Did you and or your caregivers understand what you would have to do to take care of yourself after leaving the hospital?

- Did you know what medications you would be taking and why you would be taking them after leaving the hospital?

How do patients rate the hospital?

- What number would you use to rate this hospital during your stay?

Would patients recommend the hospital to friends and family?

- Would you recommend this hospital to your family and friends?

Source: Medicare.gov (2020).

Doctors and patients often have different perspectives on healthcare quality. Even a decade ago, researchers found that patients believed treatment to be the most important aspect of quality healthcare, but their views on the key components of treatment differed from those of physicians. Patients indicated that inclusion in the decision-making process, discussion of treatment options, and instruction and education on the chosen treatment were even more important than speed and outcomes (Regula et al. 2007).

Few studies, however, report on healthcare quality improvements made as a result of patient satisfaction surveys. However, it is clear that patients appreciate good interpersonal skills such as courtesy, respect, and clear explanations and information from their healthcare provider. These skills appear to be more essential to patients than clinical skills and high-tech hospital settings (Al-Abri and Al-Balushi 2014).

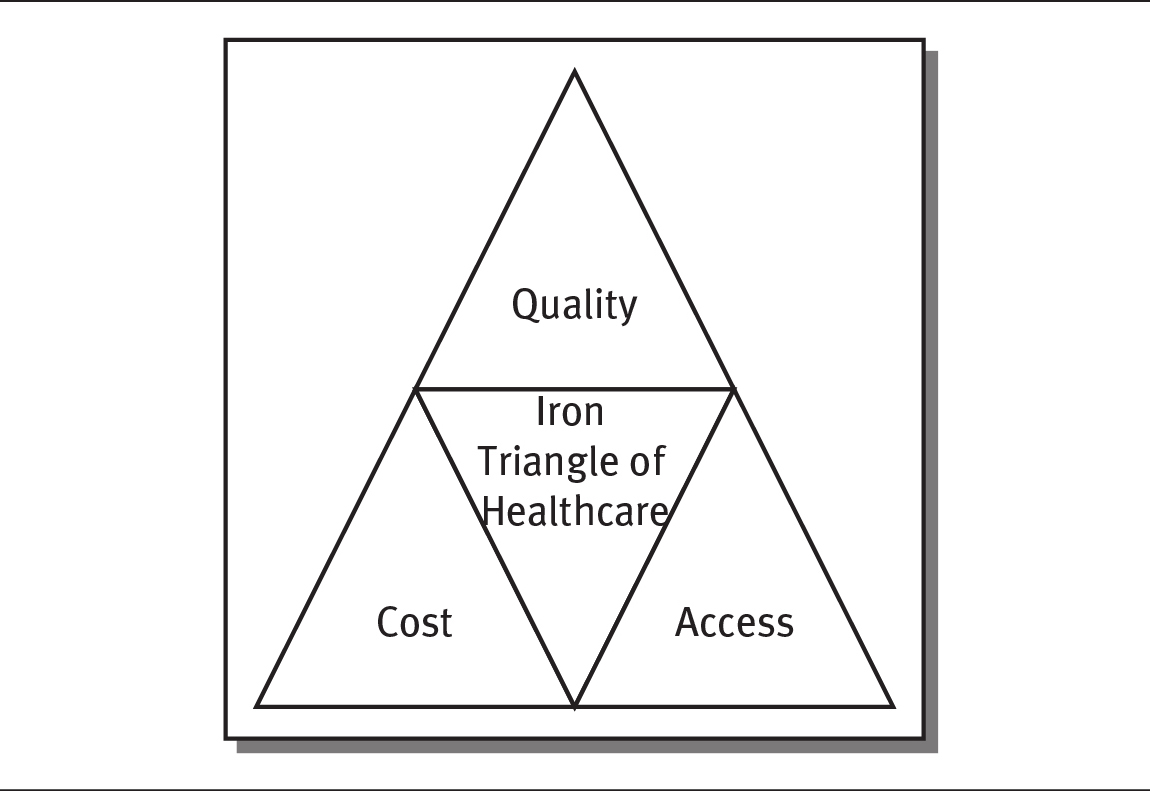

THE IRON TRIANGLE

Introduced by physician William Kissick in 1994, the “Iron Triangle” of Healthcare (discussed at length in chapter 1 and depicted again in exhibit 10.2) illustrates the competing priorities of access, cost, and quality. According to Kissick, these three factors necessarily compete with one another—that is, a change in one factor must have an impact on the other two. For instance, the increased use of medical technology from World War II to the present has improved the quality of patient care, but it has also dramatically increased costs. Similarly, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), passed in 2010, has increased access to care for many people, but it has also contributed to increased costs for taxpayers.

EXHIBIT 10.2 The Iron Triangle of Healthcare

Details

Tom Godfrey (2012) compares the Iron Triangle to a tripod, suggesting that when one leg moves, the other two must be adjusted to keep the system balanced. This argument suggests that to get better-quality care and allow everyone to access it, costs must increase.

Access refers to the ability to obtain care when it is needed. Having health insurance or the means to pay for care dramatically increases access. However, where one lives also affects access to care. Those living in rural areas of the United States often struggle to access even primary care and likely have difficulty accessing specialist health professionals.

Not everyone agrees with Kissick’s theory. Some argue that the best systems look for ways to displace existing markets, services, and alliances with a better model and that new technology should decrease cost, improve quality, and make services more accessible (Christensen, Bohmer, and Kenagy 2000). Ultrasound, for example, replaced X-ray technology in some cases, making such procedures easier and cheaper. Subsequently, existing X-ray companies did not participate in ultrasound until they saw its success and then acquired the technology (Christensen and Raynor 2003).

Some healthcare technology, such as telemedicine, is designed to increase access while potentially lowering costs and improving the quality of care. Telemedicine connects physicians and patients remotely through telecommunications and information technology. Telemedicine has been found to increase patients’ access to care, and it also lowers hospital length of stay and costs (Castro, Miller, and Nager 2014).

Balancing access, cost, and quality remains a challenge for most healthcare organizations. Some believe that the shift to value-based care will require healthcare organizations to make the following changes (Aluko 2017):

- Deliver transparent, quality outcomes for consumers and patients

- Exercise cost management and cost transparency

- Provide superior patient experiences with high patient satisfaction

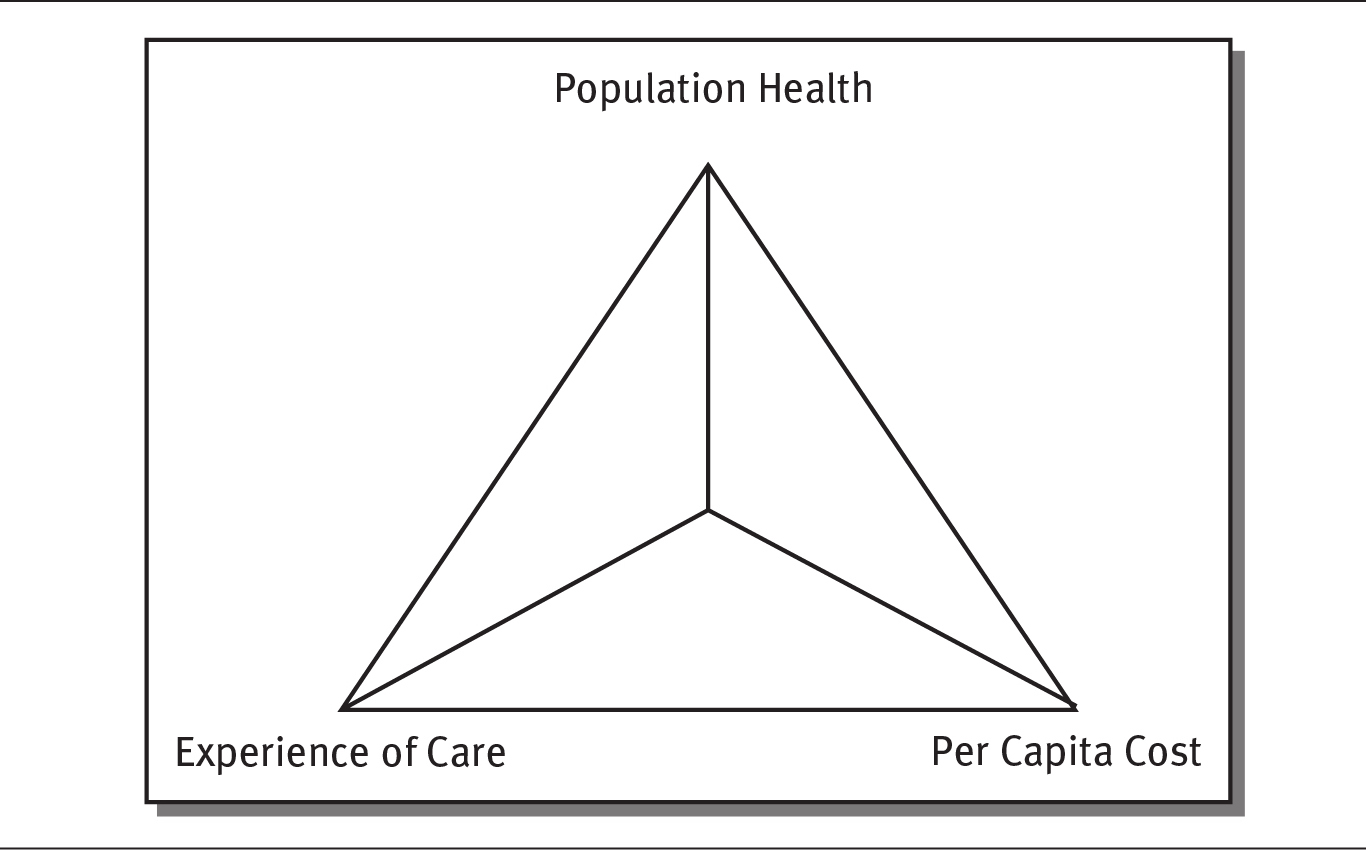

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim (discussed in chapter 1) seeks to address all three issues simultaneously.

INITIATIVES TO IMPROVE HEALTHCARE QUALITY

One of the most important initiatives to improve healthcare quality began with the Institute of Medicine’s release of its report America’s Health in Transition: Protecting and Improving Quality in 1996. The Institute concluded that a terrible quality problem existed—that “the burden of harm conveyed by the collective impact of all of our healthcare quality problems is staggering” (Chassin and Galvin 1998).

The publication of this report ignited work on assessing and improving the quality of healthcare across the United States. Subsequent efforts by the Institute of Medicine resulted in two widely read publications, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System (1999) and Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (2001). These reports focused on needed change to healthcare policy and practice in the United States. From To Err is Human, many learned of the significant amount of medical errors occurring nationally. The publication reported on tens of thousands of Americans who were dying each year as a result of medical errors. The second report defined six aims and ten rules for how care should be delivered to improve quality of care.

Other national efforts have also attempted to improve healthcare quality. A few years prior to the first Institute of Medicine report, other experts founded the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), a national healthcare organization that is focused on improving healthcare in the United States. The IHI has published extensive research of exchanging knowledge and training physicians on best practices in healthcare quality improvement. The IHI’s work has helped clinicians and other healthcare professionals form effective interprofessional teams to focus on improving healthcare delivery.

In the early 2000s, the IHI worked to change mainstream practice standards, launching what it called the “Triple Aim” (depicted in exhibit 10.3). The Triple Aim differs slightly from the Iron Triangle, as it focuses on the interdependencies of access, cost, and quality. The Triple Aim encourages healthcare organizations to focus concurrently on improving the patient experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing the per capita cost of healthcare.

EXHIBIT 10.3 The IHI Triple Aim

Details

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT EFFORTS ARE ONGOING

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT EFFORTS ARE ONGOING

Although quality improvement efforts helped decrease the number of hospital stays caused by adverse drug event (ADEs) in hospitals by 27.2 percent from 2010 to 2014, 465,000 ADEs still occurred each year during this period. Reactions to antibiotics and anti-infectives, systemic agents, and hormones were the most common causes of ADE-related hospital stays (Weiss et al. 2018).

The good news, according to the federal Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, is that the large majority of ADEs are preventable. This office, together with other organizations, is working to reduce ADEs through a variety of measures. Surveillance, or tracking, ADEs is key. Prevention measures include provider and patient education and identification of high-priority risks. Incentives and oversight are efforts to provide quality measures, policies, and reward models. Finally, research continues to identify the patients who are at highest risk of ADEs and the most effective prevention strategies (ODPHP 2014).

The IHI pilot-tested the Triple Aim in more than 100 organizations around the world. These efforts promoted a quality process that includes identifying target populations, defining system aims and measures, developing projects strong enough to effect system-level results, then rapid testing and scale-up based on local needs and conditions (IHI 2020b).

Between 2010 and 2014, the IHI continued to focus on improving the health of populations and reducing per capita healthcare costs. In 2017, the IHI merged with the National Patient Safety Foundation and has accelerated its pace of healthcare improvement (IHI 2020a).

MEDICAL AND SURGICAL ERRORS

Supporting the Institute of Medicine’s research, a Johns Hopkins University study showed that deaths attributable to medical errors in the United States exceed 250,000 per year. In 2016, that number would have been the third-leading cause of death in the United States (Johns Hopkins Medicine 2016).

The most common medical errors in hospitals are surgical errors. Errors in surgery can be catastrophic. The most common surgical errors include surgery on the wrong site or the wrong patient, the use of unsanitary equipment that causes infection, and improper surgery that damages a patient’s organs and nerves (Rogers et al. 2006). Misdiagnosis or failure to diagnose a problem are the most frequent medical errors in outpatient settings (Wallace et al. 2013).

A leading contributor to medical errors is the interaction of communication and power. Studies indicate that one major reason for malpractice lawsuits is the breakdown of communication between the physician and the patient (Huntington and Kuhn 2003). Because patient satisfaction is crucial to healthcare quality, good communication is essential. Patients who have doctors who take the time to communicate about their care are satisfied patients; satisfied patients rarely file lawsuits (Carroll 2015).

The concept of coproduction of healthcare suggests that patients, families, and healthcare professionals need to work interdependently to co-create and co-deliver care. This means that patients should be well informed and educated. They should be actively involved in decisions related to their care and its assessment. Patients and families should work proactively with the care team to determine postacute care. Clear communication throughout the process is essential (Batalden et al. 2015): “Co-production is like a new lens on patient-centered care, because it can help providers more clearly see the potential of working with patients to create better healthcare” (Kaplan 2016).

The abuse of power creates conditions in which medical errors are more likely to occur. Power differences exist in all work settings, but in healthcare, physicians in particular are used to being the “captains of their ship.” Clinicians who use their power appropriately can produce effective, positive healthcare outcomes. However, if this power is used inappropriately, communication and collaboration can break down within and across care teams, resulting in poor care. Power differences among healthcare providers, conflicting roles or role ambiguity, and interpersonal power conflicts are key sources of communication failures (Sutcliffe, Lewton, and Rosenthal 2004). Providers, staff, and patients may withhold or distort communication because of power differences. One person may perceive the other to be incompetent and therefore fail to communicate. Another might believe that a higher-status person is closed-minded (O’Daniel and Rosenstein 2008).

Research shows that effective communication results in better patient outcomes, greater patient satisfaction, and increased employee satisfaction (O’Daniel and Rosenstein 2008). Two techniques have been shown to be particularly effective in communication and quality care: SBAR and AIDET. The situation-background-assessment-recommendation, or SBAR, technique is a systematic framework for clinics to gather, assess, and share information. It allows nurses, for example, to assess and record changes in a patient’s status and communicate key clinical information to the physician.

AIDET is a communication technique that is used directly with patients. In this process, the patient is acknowledged by his or her full name, as are family members and visitors in the room. The healthcare professionals then identify themselves and indicate their role. They make clear the steps of the procedure taking place and the duration of the procedure. The next step is to answer any questions and clearly explain. Finally, the healthcare worker thanks the individual for choosing the facility and summarizes the patient’s visit (Burgener 2017).

DEBATE TIME Rural Health and the Triple Aim

DEBATE TIME Rural Health and the Triple Aim

Hospitals in rural America are especially dependent on revenues from elective and nonemergency procedures. However, patients often have difficulty paying for this care. For some, such procedures must be paid for out of pocket because they are not covered by insurance. Transportation is a problem for some individuals, as is finding available appointments. Recruiting healthcare professionals is also tough in rural locations.

Considering the Triple Aim, discuss the provision of healthcare in rural America from three perspectives. First, what are the needs of the population? Consider, for example, maternal and other basic types of care. Second, with limited revenues, how does a small hospital cover costs? Third, how do hospital staff maintain or improve quality, especially when there is a limited workforce?

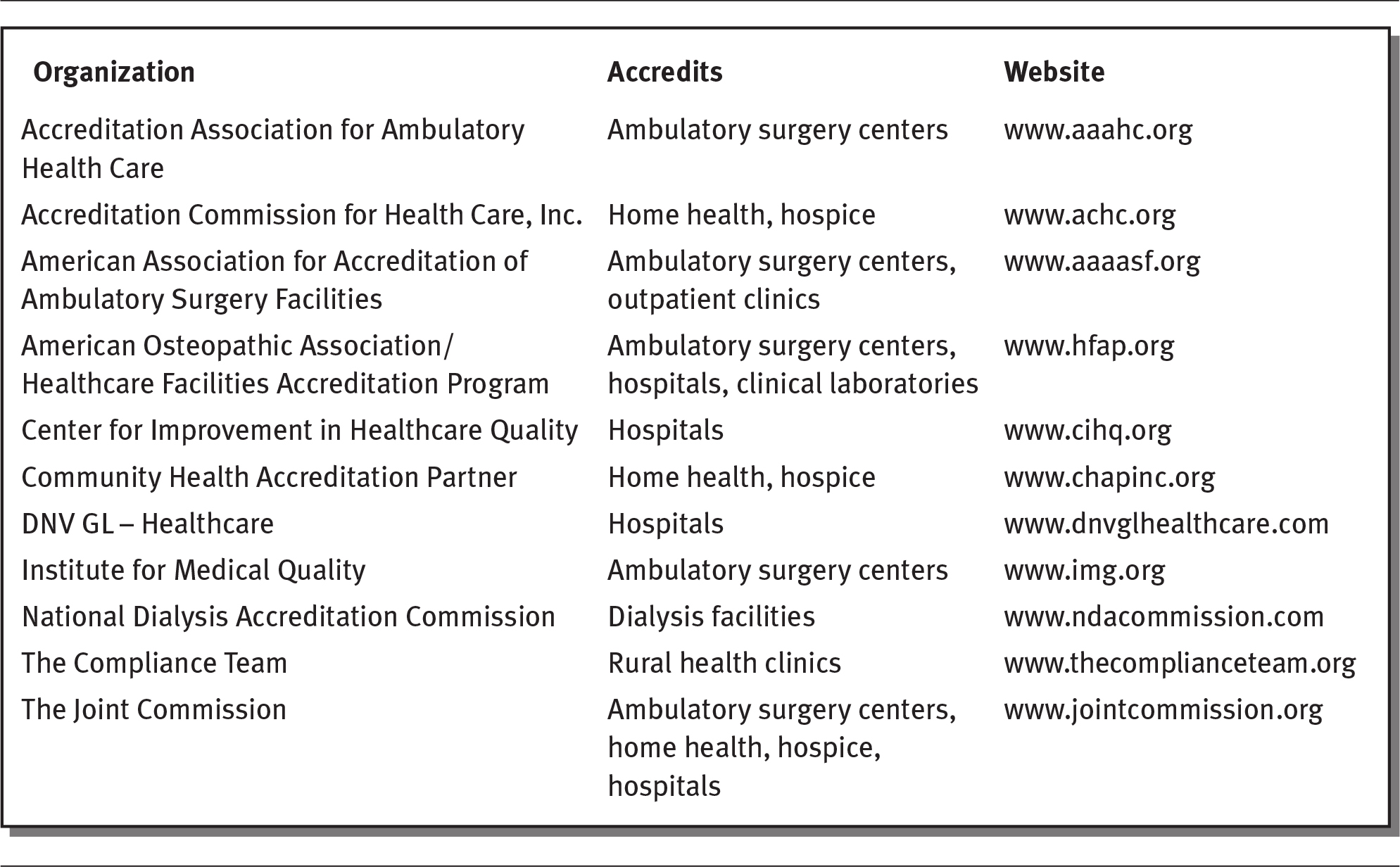

ACCREDITING ORGANIZATIONS

Healthcare organizations are inspected and accredited by a variety of accrediting bodies. Accreditation teams visit a healthcare organization to identify areas of improvement. Organizations that meet the set of standards established by the accrediting body are accredited. Accreditation is “a symbol of quality that reflects an organization’s commitment to meeting certain performance standards” (The Joint Commission 2020a). The purpose of accreditation is to help providers to improve healthcare quality and to signal to the public that they meet the standards and regulations of a recognized external body.

The largest accrediting organization in the United States is The Joint Commission, which accredits around 88 percent of US hospitals (Jha 2018). Many healthcare organizations are required to have some form of external accreditation. For instance, the CMS requires hospitals receive accreditation from a recognized accrediting body or pass a state inspection to receive Medicare payments. In 2019, CMS had approved 11 different accrediting organizations (see exhibit 10.4).

EXHIBIT 10.4 Accrediting Organizations Approved by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Details

The details of the organization, accredits, and websites are as follows:

- Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care; Ambulatory surgery centers; www.aaahc.org.

- Accreditation Commission for Health Care, Inc.; Home health, hospice; www.achc.org.

- American Association for Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities; Ambulatory surgery centers, outpatient clinics; www.aaaasf.org.

- American Osteopathic Association or Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program; Ambulatory surgery centers, hospitals, clinical laboratories; www.hfap.org.

- Center for Improvement in Healthcare Quality; Hospitals; www.cihq.org.

- Community Health Accreditation Partner; Home health, hospice; www.chapinc.org.

- DNV GL - Healthcare; Hospitals; www.dnvglhealthcare.com.

- Institute for Medical Quality; Ambulatory surgery centers; www.img.org.

- National Dialysis Accreditation Commission; Dialysis facilities; www.ndacommission.com.

- The Compliance Team; Rural health clinics; www.thecomplianceteam.org.

- The Joint Commission; Ambulatory surgery centers, home health, hospice, hospitals; www.jointcommission.org.

Source: CMS (2019a).

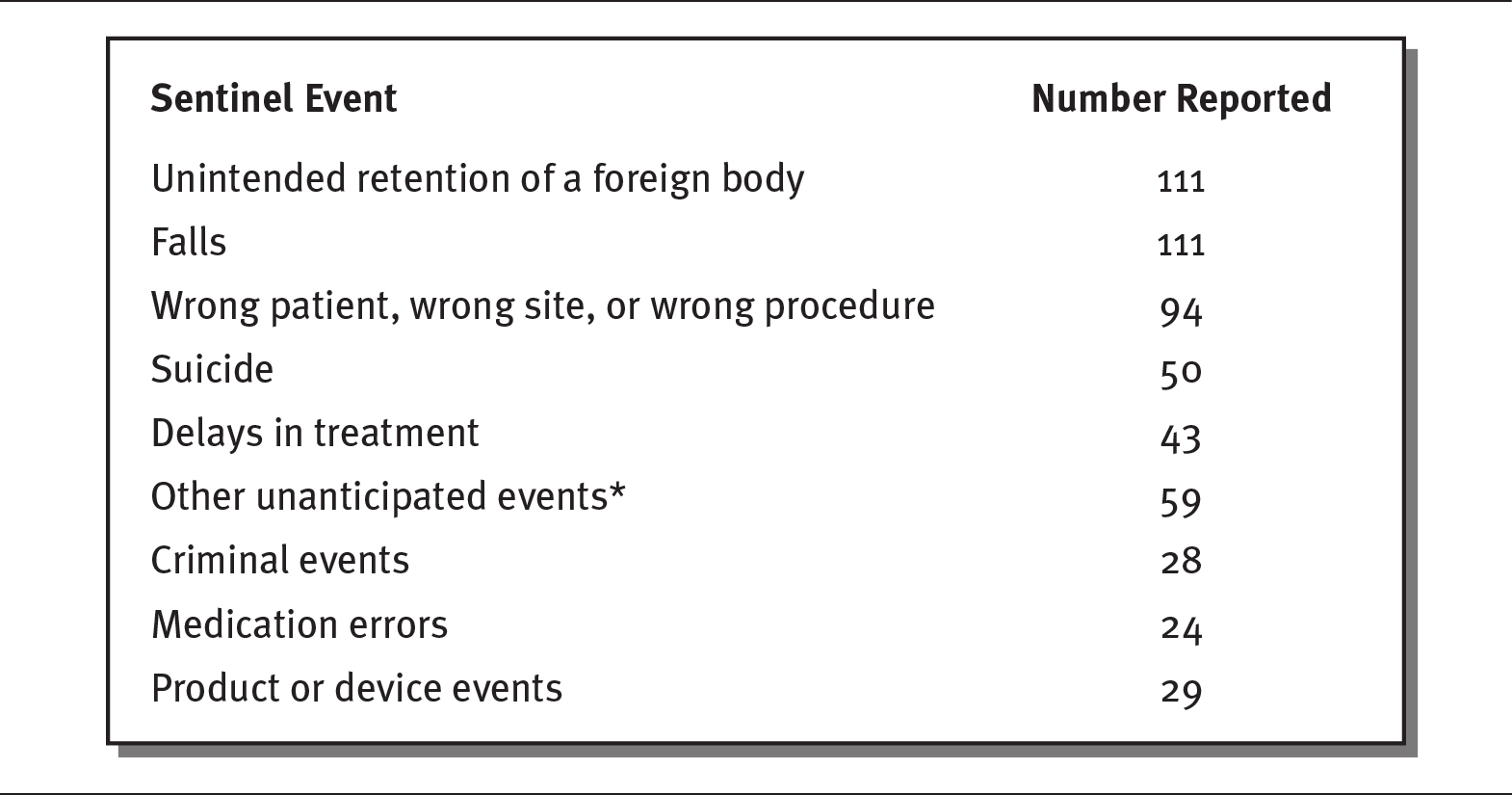

SENTINEL EVENTS

The Joint Commission uses the term sentinel event to refer to occurrences that lead to a patient’s death or serious injury, including psychological injury. Sentinel events also include the loss of a limb or function (The Joint Commission 2013). The Joint Commission collects data and reports on the most common sentinel events occurring each year. Hospitals voluntarily report these events, so the data may represent only a fraction of the events that actually take place. Exhibit 10.5 lists the ten most common sentinel events reported in 2018.

EXHIBIT 10.5 Ten Most Common Sentinel Events Reported to The Joint Commission, 2018

Details

The details of the sentinel events and the number reported are as follows:

- Unintended retention of a foreign body: 111

- Falls: 111

- Wrong patient, wrong site, or wrong procedure: 94

- Suicide: 50

- Delays in treatment: 43

- Other unanticipated events (asterisk): 59

- Criminal events: 28

- Medication errors: 24

- Product or device events: 29.

Note below shows asterisk as: Includes asphyxiation, burns, choking, drowning, and being found unresponsive.

* Includes asphyxiation, burns, choking, drowning, and being found unresponsive.

Source: The Joint Commission (2019a).

The Joint Commission determines the highest-priority patient safety issues and develops the National Patient Safety Goals to reduce or eliminate those concerns in hospitals, behavioral health facilities, home health care agencies, ambulatory healthcare settings, and critical access hospitals. The Joint Commission set the following goals for 2019 (The Joint Commission 2019b).

Identify patients correctly. Use two identifiers, such as the patient’s name and date of birth, to make sure the right patient gets the correct medicine and treatment.

Identify patients correctly. Use two identifiers, such as the patient’s name and date of birth, to make sure the right patient gets the correct medicine and treatment.

Improve the effectiveness of communication among caregivers. Get test and diagnostics results to the right people on a timely basis.

Improve the effectiveness of communication among caregivers. Get test and diagnostics results to the right people on a timely basis.

Improve the safety of using medications. Label all medications and medication containers.

Improve the safety of using medications. Label all medications and medication containers.

Use alarms safely. Manage alarms to make sure they are heard and responded to on time.

Use alarms safely. Manage alarms to make sure they are heard and responded to on time.

Prevent infection. Use hand-washing guidelines provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization.

Prevent infection. Use hand-washing guidelines provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization.

Identify patient safety risks. Identify patients who are at risk for suicide.

Identify patient safety risks. Identify patients who are at risk for suicide.

Prevent mistakes in surgery. Make certain that the correct surgery is done on the correct patient and at the correct place on the patient’s body.

Prevent mistakes in surgery. Make certain that the correct surgery is done on the correct patient and at the correct place on the patient’s body.

Hospitals bear the responsibility for eliminating sentinel events and improving patient safety. Hospitals should identify safety risks inherent in their patient populations (see sidebar).

THE CASE OF JOAN MORRIS

THE CASE OF JOAN MORRIS

Joan Morris, a 67-year-old woman, was admitted to a teaching hospital for the treatment of two brain aneurysms. One was successfully treated with angiography; the other was to be treated surgically on an upcoming day. After the first procedure, Joan was taken to the wrong unit, rather than to the room she had been assigned. Then, Joan was mistaken for a woman with a similar name. On day two, Joan was given an invasive heart study—not the woman who should have received it. This happened even after Joan told the clinicians she did not want any further procedures to be done. About and hour into the study, it became clear to the clinicians that Joan was the wrong patient, and the study was stopped. The patient who actually needed the heart study was eventually treated. The entire event was replete with communication errors, and it was clearly a serious reportable event (Chassin and Becher 2002).

This is an example of a serious mistake that could have resulted in a deadly outcome. Had Joan’s aneurysms not been treated, she could have had a stroke or even died. If the error had not been discovered, the other patient would not have received the heart study she needed.

Similar to The Joint Commission’s sentinel events and National Patient Safety Goals is the list of preventable clinical events published by the National Quality Forum (NQF). This nonprofit group uses evidence-based measures and standards of care to develop a list of serious reportable events (also known as never events) to assess and report on the performance of healthcare organizations related to safe patient care. Exhibit 10.6 presents examples of serious reported events.

EXHIBIT 10.6 Serious Reportable Event Categories According to the National Quality Forum

Details

The details are as follows:

- Surgical or invasive procedure events such as surgery on the wrong site or performed on the wrong patient. Foreign objects left in the patient would also be included.

- Product or device events include death associated with contaminated devices or drugs, germs or disease in the surgery rooms, and medical equipment that malfunctions.

- If a patient is not capable of making decisions but is released to someone other than an authorized person that is included on the NQF list. So is death or injury associated with the patient disappearing. Suicide or attempted suicide while in a healthcare setting is included in this category.

- Care management events include medication errors, death from unsafe blood products, maternal death from labor and delivery, artificial insemination with the wrong donor sperm or wrong egg, or death/serious injury from not communicating lab, pathology or diagnostic exam results.

- Electrocution or electric shock, giving oxygen or the wrong gas, death or injury from burns, or injury from restraints are identified as environmental events.

- Death or serious injury from MRI accidents is a category of its own.

- Potential criminal events include care ordered by someone impersonating a clinician, abduction of a patient, sexual abuse or assault, and physical assault or battery at a healthcare setting.

Source: NQF (2020).

QUALITY IMPROVEMENT TOOLS

A number of well-established quality improvement tools exist. One prominent tool used by the IHI is called the Model for Improvement. This model asks questions such as “What are we trying to accomplish?” “How will we know that a change is an improvement?” and “What change can we make that will result in improvement?” (IHI 2020c). These questions serve as a starting point for other quality improvement tools.

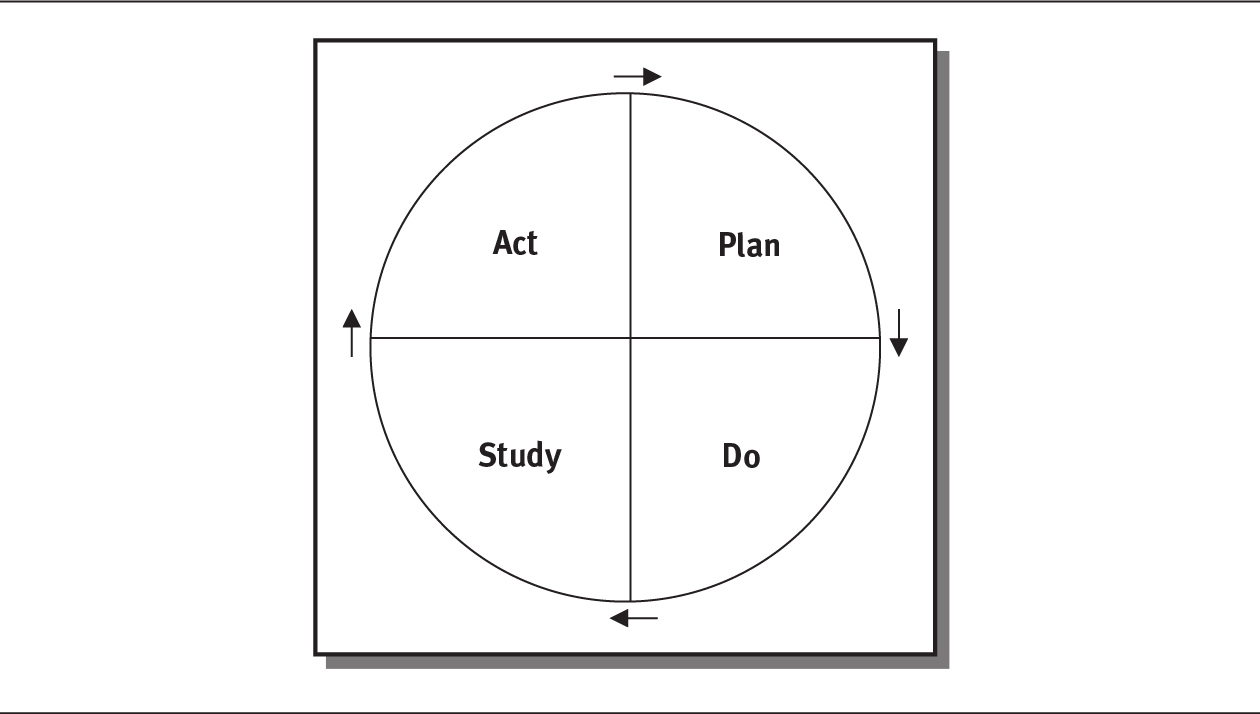

PLAN-DO-STUDY-ACT

The Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle (see exhibit 10.7), also known as the “Deming Wheel,” was introduced to the management thinker W. Edwards Deming by his mentor, Walter Shewhart of Bell Laboratories in New York (W. Edwards Deming Institute 2020). The first step in the cycle, Plan, begins by answering the initial questions in the IHI’s Model for Improvement. A goal or purpose is established, along with a method of defining and measuring success. The Do step puts the plan into action. During the Study step, data are gathered to gauge progress or success. The final step, Act, allows for the entrenchment of a successful result or a change in the goal, methods, or the entire process.

EXHIBIT 10.7 Plan-Do-Study-Act Cycle

Details

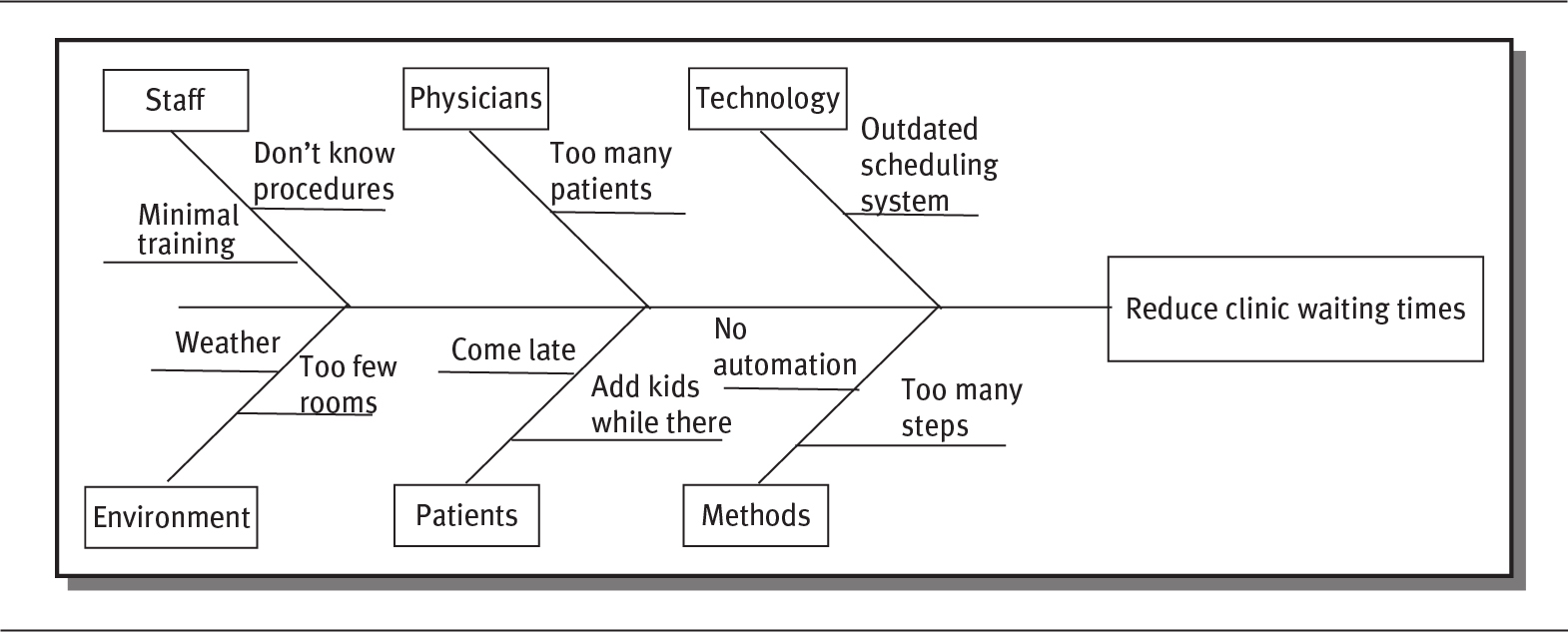

CAUSE-AND-EFFECT DIAGRAM

A cause-and-effect diagram graphically depicts the strategy for achieving a specific outcome (effect) and the factors that influence that outcome (causes). It is often referred to as a “fishbone diagram,” because it resembles a fish skeleton (see exhibit 10.8 for an example). The first step is to identify a problem statement, shown in the box on the right-hand side of the diagram. Major causes of the problem, given generic headings, are then added as shown in the boxes. These causes can be anything, but in a classical design, they include materials, methods, equipment, environment, and people. Finally, causes are listed related to each category. Finally, all of the possible causes of the problem are added to the branches connected to the boxes (IHI 2017).

EXHIBIT 10.8 Example of a Cause-and-Effect Diagram

Details

Problem statement: Reduce clinic waiting times. The problem and related cause leading to the statement are as follows:

- Staff: Don’t know procedures, Minimal training.

- Physicians: Too many patients.

- Technology: Outdated scheduling system.

- Environment: Weather, Too few rooms.

- Patients: Come late, Add kids while there.

- Methods: No automation, Too many steps.

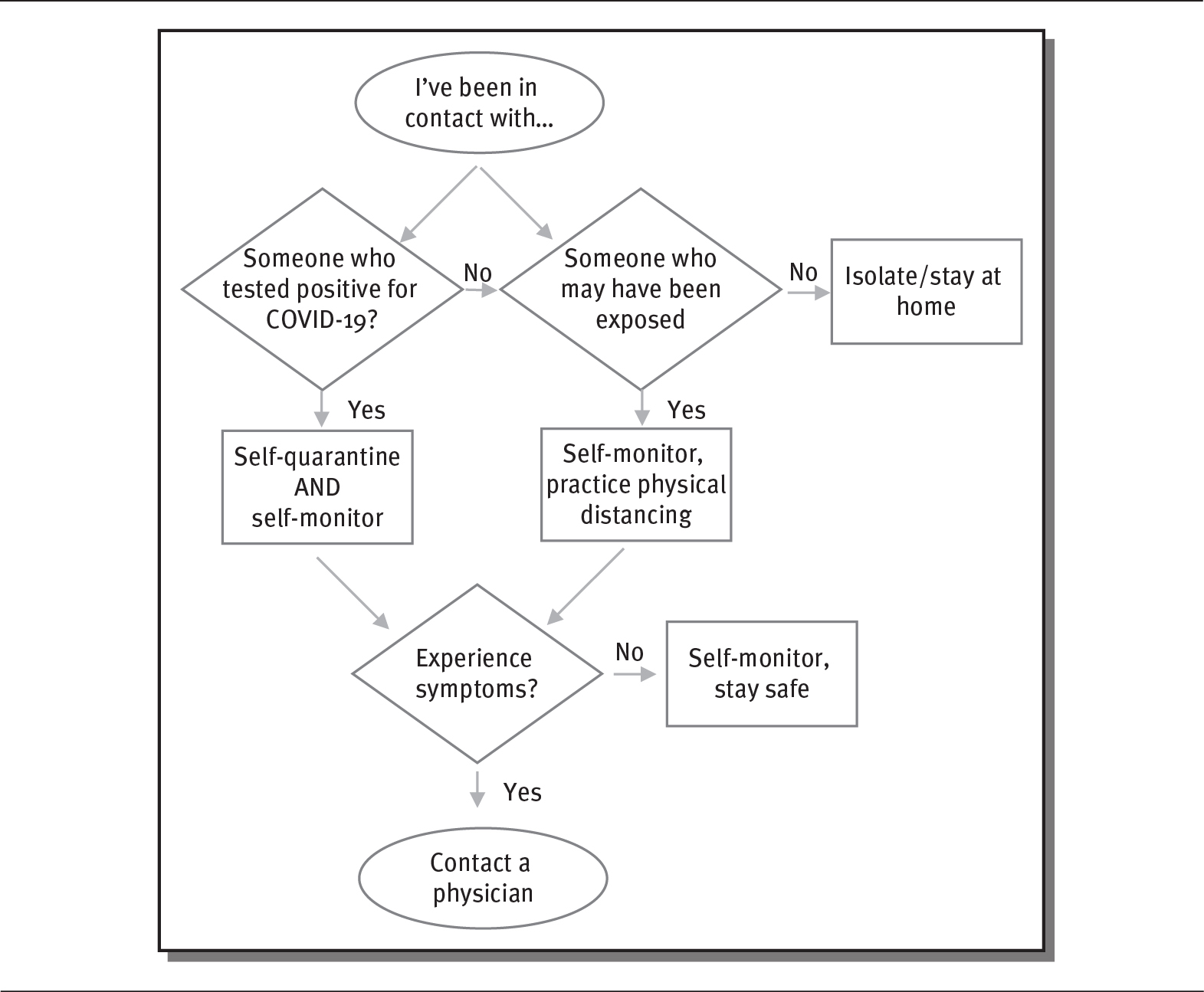

FLOWCHART

A flowchart is sometimes used to map out a process or a group of processes, clearly identifying each step. As shown in exhibit 10.9, ovals indicate the beginning and end of a process, and a box represents each activity or task. A diamond-shaped box is used to identify a decision point (yes or no). The visual presentation helps teams identify problems or bottlenecks and focus on areas of improvement (IHI 2017).

EXHIBIT 10.9 Example of a Simple Flowchart

Details

The details are as follows:

I’ve been in contact with… is in an oval box. The oval box branches into two diamond boxes:

- Someone who tested positive for COVID-19?

- If yes, Self-quarantine and self-monitor, which further leads to Experience symptoms?

- If yes, contact physician

- If no, self-monitor, stay safe.

- If yes, Self-quarantine and self-monitor, which further leads to Experience symptoms?

- Someone who may have been exposed

- If yes, Self-monitor, practice physical distancing, leading to Experience symptoms?

- If yes, contact physician

- If no, self-monitor, stay safe.

- If no, isolate or stay at home.

- If yes, Self-monitor, practice physical distancing, leading to Experience symptoms?

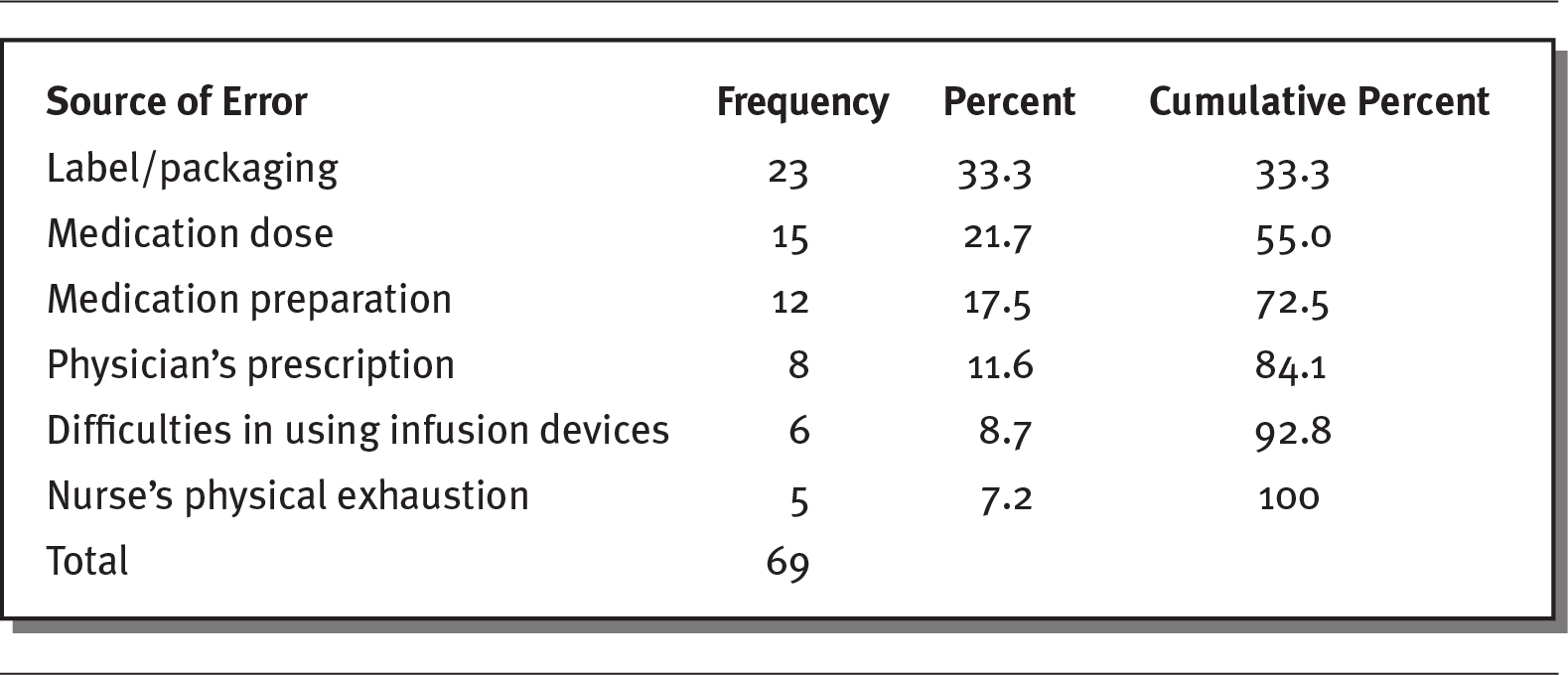

PARETO CHART

The “Pareto principle” holds that for most events, 80 percent of the effects are caused by 20 percent of the causes; for this reason, it is also called the “80/20 rule” (IHI 2017). A Pareto chart allows for the identification of the causes that contribute to an overall effect.

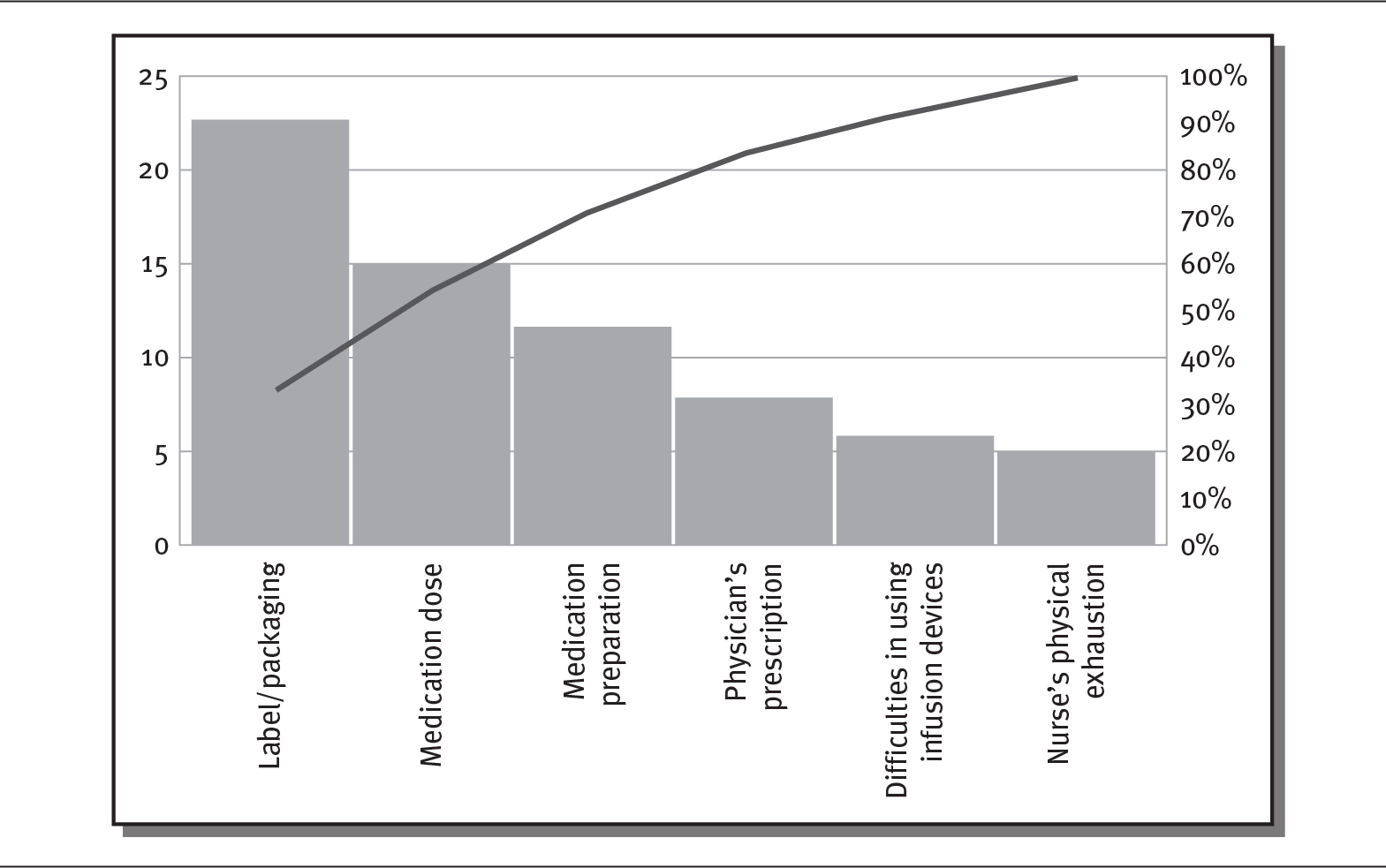

Teams use the information to address the factors causing the majority of the effect. A Pareto chart helps teams concentrate on matters of greatest impact. Exhibit 10.10 presents hypothetical data on sources of medication errors, and exhibit 10.11 uses those data to create a Pareto chart.

EXHIBIT 10.10 Sources of Medication Errors

Details

The details of the sources of error, frequency, percent, and cumulative percent respectively are as follows:

- Label or packaging: 23, 33.3, 33.3.

- Medication dose: 15, 21.7, 55.0.

- Medication preparation: 12, 17.5, 72.5.

- Physician’s prescription: 8, 11.6, 84.1.

- Difficulties in using infusion devices: 6, 8.7, 92.8.

- Nurse’s physical exhaustion: 5, 7.2, 100.

- Total: 69.

EXHIBIT 10.11 Pareto Chart of Medication Errors

Details

The x-axis shows medication errors. The y-axis on the left shows frequency from 0 to 25 in increments of 5. The y-axis on the right shows percentage from 0 to 100 in increments of 10. The frequency, depicted as a bar graph, shows a decreasing trend while the percent, depicted as a line graph, shows an increasing trend. The details are as follows:

- Label or packaging: 23, 33.3 percent.

- Medication dose: 15, 55.0 percent.

- Medication preparation: 12, 72.5 percent.

- Physician’s prescription: 8, 4.1 percent.

- Difficulties in using infusion devices: 6, 92.8 percent.

- Nurse’s physical exhaustion: 5, 100 percent.

OTHER TOOLS

Many other quality improvement models and methodologies exist, such as root cause analysis, Six Sigma, Lean (Hughes 2008), and the change acceleration process, in addition to the many tools used within these methodologies, such as driver diagrams, failure modes and effects analysis, histograms, run and control charts, and scatter diagrams (IHI 2017). Many of the tools introduced in this chapter were created in other industries and adapted for use in healthcare to improve systems and processes, which typically are the causes of most medical errors rather than the behaviors of individual physicians or staff members. Many of these tools can be used together as part of a process improvement project. For instance, a fishbone diagram or Pareto chart might be used to identify some aspect of a process that needs improvement, and then PDSA can be employed to test improvement processes.

Such tools help identify the root causes of error, provide an understanding of the significance of error, track and monitor performance, and standardize successful protocols. Quality improvement tools can be used to make positive changes to faulty processes and enable organizations to implement effective solutions. These solutions might be as simple as a surgical time-out checklist to prevent surgical errors, or they may use sophisticated technology such as an automated pharmacy system. Process improvement tools provide constructive feedback, allowing organizations to accurately identify process issues and more effectively address quality and patient safety concerns (Hughes 2008).

Six Sigma approaches business processes improvement with qualitative and quantitative techniques to increase performance and reduce variation. These tools include statistical control charts, failure modes and effects analysis, and process mapping:

Statistical control charts. Graphs used to study how a process changes over time. Graphs contain a central line for the average and upper and lower control limits.

Statistical control charts. Graphs used to study how a process changes over time. Graphs contain a central line for the average and upper and lower control limits.

Failure modes and effects analysis. Analysis of the ways or modes that something might fail. Failures include errors and defects that can potentially impact a consumer.

Failure modes and effects analysis. Analysis of the ways or modes that something might fail. Failures include errors and defects that can potentially impact a consumer.

Process mapping. A tool that visually shows the flow of work and the series of events that produces a desired result.

Process mapping. A tool that visually shows the flow of work and the series of events that produces a desired result.

Lean, which is often merged with Six Sigma to become Lean Six Sigma, seeks to reduce waste and increase value to the consumer. It identifies what adds value, enhances this, and seeks to reduce other actions and processes that do not add value. Lean focuses on areas such as transportation, inventory, motion, waiting, overproduction, overprocessing, and defects (Kanbanize 2019).

Benchmarking to both internal and external standards is another quality improvement tool. Benchmarking involves continual comparison to best performers (Gift and Mosel 1994). Internal benchmarking looks at the best outcomes internally and the processes involved in achieving them. External benchmarking allows for new ideas or practices that have not yet been incorporated by a healthcare organization. It uses comparative data to judge performance and identify possible improvements (Hughes 2008).

With all of these tools, surveys, and approaches to improved quality, some would say there is little evidence to suggest that many of the quality measures have led to significantly improved health outcomes. They would argue that to truly improve healthcare quality a greater focus on patient-centered outcomes needs to occur (Saver et al. 2015).

HIGH-RELIABILITY ORGANIZATIONS

HIGH-RELIABILITY ORGANIZATIONS

The US healthcare system has long been funded through a fee-for-service payment model that reimburses providers based on the amount of business they generate. This model encourages high-cost services that result in a high profit margin for the hospitals and physicians who offer them. With rising healthcare costs in mind, an effort is underway to promote better quality, reduced errors, and less business in the form of readmissions to hospitals or unnecessary care in settings like the emergency department.

High-reliability organizations (HROs) are touted as a model to provide consistent quality in healthcare. Leadership of HROs is committed to the goal of zero harm. HROs create a culture in which all staff are empowered to speak up. HROs provide tools to address improvement opportunities and create lasting change (The Joint Commission 2020b). HROs focus on six fundamental elements:

- Sensitivity to operations or recognizing potential error

- Avoiding simple explanations of failure; asking a number of questions to find all of the causes of problems

- Predicting and eliminating problems before they happen

- Deference to expertise—those with the most knowledge relevant to an issue deal with it

- Dealing quickly with difficulties so that systems are resilient and function effectively

- Collective mindfulness that allows for continuous learning and making critical adjustments to meet challenges

Increasing numbers of providers have joined this movement over the past 20 years (Deloitte 2017).

VALUE-BASED CARE

As discussed in chapter 9, in an effort to improve quality and reduce healthcare spending, the federal government and some insurance companies have changed the way they pay for care to reward positive quality outcomes. The federal government has been experimenting with this payment method for many years. Medicare’s value-based purchasing refers to a set of performance-based payment strategies that the federal government has been testing and reviewing since the 1990s. Value-based payment is also known as pay-for-performance reimbursement. CMS has implemented value-based programs for end-stage renal disease, hospital purchasing, hospital readmission rates, physician services, hospital acquired conditions, skilled nursing facilities, and home health care (CMS 2020b).

Evidence suggests that value-based payment methods have achieved only modest success in improving performance, but public and private payers continue to try new models, including some directed by the ACA (Damberg et al. 2014) (see sidebar). National studies suggest that value-based payment methods are becoming more popular, as about 40 percent of commercial payments to physicians and hospitals now include a quality component, compared with 11 percent in 2013 and only 1 to 3 percent in 2010 (Zimlich 2017).

VALUE-BASED PAYMENT PROGRAMS

VALUE-BASED PAYMENT PROGRAMS

The concept of payment based on quality of care has been around for many years, but the passage of the ACA in 2010 put new emphasis on value-based payment. CMS (2020b) operates seven value-based programs that have been linked to better care for individuals, better health for populations, and lower costs of healthcare.

- End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program

- Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program

- Hospital Readmission Reduction Program

- Value Modifier Program (also called the Physician Value-Based Modifier)

- Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program

- Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Program

- Home Health Value-Based Program

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recognizes that many value-based payment models will directly affect its members. It has suggested a number of necessary principles for policymakers in designing these models:

Being responsive to community needs preferences and resources

Being responsive to community needs preferences and resources

Being responsive to individual patient preferences

Being responsive to individual patient preferences

Focusing on tangible improvements in clinical outcomes

Focusing on tangible improvements in clinical outcomes

Family physicians want to see value-based care reduce the per person cost of healthcare and standardize payment models and performance measures among payers, providers, purchasers, and patients. Balancing the administrative burden and costs to physicians with the proposed improvements of value-based payment may be difficult (AAFP 2016). Value-based care may be the future of healthcare, but most recognize that it still needs continued design improvement.

INEQUALITIES AND QUALITY

Compared with ten other high-income countries, including Germany, Sweden, and France, the United States has the highest healthcare costs and the worst outcomes. The United States ranks at the bottom of the group in terms of equity, access, and healthcare outcomes. Costs impede access to healthcare in the United States more than in other countries. Americans also have significant difficulty paying medical bills and waiting for appointments. In addition, fewer Americans have a regular doctor. The United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Sweden rank highest on measures related to equity. These three countries also show small differences between lower- and higher-income adults on 11 measures (Schneider et al. 2017).

Economic inequality between the rich and the poor is widening in the United States. Americans with incomes below the federal poverty level have worse access to care than wealthy Americans. Many low-income people remain uninsured, as wages have not kept pace with rapidly rising insurance premiums and patient cost-sharing plans. The life expectancy of the wealthiest Americans now exceeds that of lower-income Americans by 10 to 15 years (Dickman, Himmelstein, and Woolhandler 2017). Health differences between higher- and lower-income groups have changed dramatically, with the low-income Americans having life expectancies equal to those of people living in Sudan or Pakistan, while the richest Americans outlive people in all other countries (Neilson 2019).

The ACA improved coverage for lower-income Americans, women, and minorities, but its overall impact was limited by the choice of many states not to expand their Medicaid programs, which left many people without health insurance. As of 2017, 29 million Americans remained uninsured. Substantial inequalities still exist along economic, gender, and racial lines (Gaffney and McCormick 2017).

The term structural racism refers to the variety of ways in which societies are organized to perpetuate racial discrimination in housing, education, media, healthcare, criminal justice, and other areas (Bailey et al. 2017). Negative policies and practices reinforce discrimination, beliefs, values, and the distribution of resources. A focus on structural racism offers a promising approach to improving healthcare equity.

There is also evidence that hospitals vary in the quality of care they deliver to patients according to the type of insurance they have—or the lack thereof. People with private insurance typically have better outcomes and lower death rates than Medicare enrollees. Given this, hospitals might want to measure the quality of care given to different insurance groups to better understand quality outcomes (Spencer, Gaskins, and Roberts 2013).

SUMMARY

The Institute of Medicine defined healthcare quality decades ago; however, clinicians, patients, and administrators may have different perspectives on quality, viewing it through the lenses of their education, training, and experience. Patients, for example, may forgive disappointing clinical outcomes if they receive excellent service. Many different measures of quality exist. One quality report specific to hospitals is the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS), which asks patients about their experiences and is used by hospitals to improve the healthcare experience. This survey is created by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which publishes HCAHPS results quarterly.

William Kissick introduced the concept of the “Iron Triangle” of Healthcare in 1994. The Iron Triangle captures three dimensions of healthcare: access, cost, and quality. Many have argued that to get better quality and access, costs must increase. Not everyone agrees with this argument. The Institute of Medicine wrote as early as the 1990s of the need to improve both healthcare policy and practice. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the “Triple Aim,” which focuses on improving the patient care experience, improving the health of populations, while simultaneously reducing the per capita cost of health.

Medical errors are a significant problem in the United States. Studies show that hundreds of thousands of errors occur each year in US healthcare organizations. The concept of coproduction of healthcare suggests that patients, families, and healthcare professionals must work interdependently to reduce error. Better communication and an understanding of power dynamics in these relationships is vital. Hierarchies among healthcare providers, conflicting roles and role ambiguity, and interpersonal power conflicts are sources of communication failures that contribute to medical errors.

Research shows that effective communication results in better patient outcomes, greater patient satisfaction, and increased employee satisfaction. Ongoing efforts have been made to improve communication within and between healthcare teams to reduce medical and surgical errors. Two techniques have been shown to be particularly effective in improving communication and the quality of care are SBAR (situation-background-assessment-recommendation) and AIDET (acknowledge-identify-duration-explain-thank).

Sentinel events are significant failures that lead to a patient’s death or serious injury. The Joint Commission identifies unintended retention of a foreign body; falls; wrong patient, wrong site, or wrong procedure errors; suicide; and delays in treatment among the top occurrences in the United States. The National Quality Forum also tracks medical errors by maintaining a list of “serious reportable events.”

Healthcare professionals and other business leaders use a variety of tools to monitor, assess, and improve quality. Common among them are the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle, cause-and-effect diagrams, flow charts, and Pareto charts.

CMS is using the evidence it gathers to develop performance-based payment strategies called value-based purchasing. This method reimburses hospitals and physicians based on a set of patient outcomes and other quality components related to end-stage renal disease, hospital purchasing, hospital readmission rates, physician services, hospital-acquired conditions, skilled nursing facilities, and home health care. While this concept has been around for some time, the passage of the ACA provided incentives to implement value-based payment.

All of these initiatives have yet to solve the inequalities between the rich and poor in the United States. Structural racism is also a cause of health inequalities. Increased focus on structural racism and on providing access to healthcare for the poor who are uninsured is needed.

QUESTIONS

- How would you define healthcare quality?

- What does the HCAHPS survey purport to do?

- William Kissick’s “Iron Triangle” attempted to define the relationship between three dimensions of healthcare. What are the three dimensions?

- What are the goals of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “Triple Aim”?

- A 2016 Johns Hopkins University study suggested that deaths attributable to medical errors exceed 250,000 a year. Where would this cause of death rank in the CDC’s leading causes of death if it were included as such? (You may have to do a quick search of the CDC’s leading causes of death.)

- What aspects of power among providers, patients, and family members affect healthcare outcomes? What is a sentinel event?

- According to The Joint Commission, what were the top three sentinel events in 2017?

- What are “never events”?

- What percentage of commercial payments to hospitals include a quality component?

- As of 2017, how many Americans were uninsured?

ASSIGNMENTS

- Compare and contrast three types of quality improvement tools. Suggest situations in which each of the three tools might be most useful.

- The Joint Commission reported that unintended retention of a foreign body and falls were the top two sentinel events in 2018. Develop and write about steps that might be taken to reduce each of those problems.

- Consider the following conversation between a physician and a patient. What opportunities for misunderstanding or miscommunication can you identify?

Doctor: “I have the results from your test we did on your prostate gland. It came back positive.”

Patient: “Wow, that is great!”

Doctor: “I don’t think it is great, but we haven’t made a diagnosis yet.”

Patient: “What is so hard about diagnosing a positive result?”

Doctor: “Well, we will need you to stay in the hospital today for observation.”

Patient: “Is there something in particular that you want me to observe?”

Identify what the physician is trying to say and how the patient is interpreting the message. What needs to be done for proper communication to take place?

CASES

WAITING, WAITING, WAITING …

Tim manages a medical clinic with 135 physicians serving a county with a population of 250,000. The clinicians specialize in everything from primary care to urology. The clinic is home to a laboratory, X-ray facility, and outpatient surgery. Patients call to make appointments, and in most cases, they have to wait several days or longer to get in. Once they make it to their appointment, some patients have to wait to get into a room. In making rounds one day, Tim found one patient who had been waiting for 45 minutes and had not even had contact with a receptionist. No one noticed she had been sitting there all that time.

The clinic uses several criteria to slot the patients into appointment times. Some physicians, for example, see a patient and then require an X-ray during the appointment. Other visits are more straightforward and require little time. Most physicians want to see four patients per hour. They definitely do not want any empty appointment slots.

Some patients want to be seen for what they consider urgent needs but in fact are often mild fevers or sore throats. These patients are invited to fill the appointment slots that are left. Some doctors will fit patients in even though they have a full schedule. Some parents bring more than one child to a single appointment. Every day, emergencies occur, ranging from serious medical problems that take extra time to particularly harsh weather that slows or stops patients and staff from coming in.

All of the scheduling is done centrally by staff who are not clinically trained. Some longtime staff know many of the physicians. Some of the scheduling staff are relatively new. They receive on-the-job training and follow written protocols as they schedule appointments. However, most of the staff doing the scheduling are not familiar with the many procedures that take place in the clinic.

Discussion Questions

- Using a cause-and-effect diagram, identify the problems you see in the clinic’s scheduling process.

- Choose one of the key issues listed on the cause-and-effect diagram and use the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to show how you would attempt to improve the process.

- Consult the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Quality Improvement Essential Toolkit at www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/Quality-Improvement-Essentials-Toolkit.aspx. or do some research on your own to find another quality improvement tool. Explain how you might use that tool to tackle this case.

A MOTHER’S INSTINCT

An 18-month-old child was admitted to the hospital after falling into a hot bath. Two weeks later, she was doing well and set to return home. Her mother noticed that the little girl asked for a drink every time she saw one, and she often sucked on a wet washcloth. When the child’s mother asked about this behavior, the nurses told her it was normal—they would not ask a physician for permission to give the girl a drink. The nurses told the mother that her child was doing well and that she should go home and get some sleep.

When the mother returned early the next morning, she knew that something was very wrong with her child. The medical team was notified. They administered naloxone, a drug used to block the effects of opioids. They finally allowed the girl to have a drink, and she swallowed a liter of juice. The medical team determined that the girl should not be given any more narcotics. They gave verbal orders.

A nurse entered the girl’s room that afternoon with a syringe of methadone. The mother reminded her that no narcotics were to be given. The nurse said that the orders had been changed and gave the little girl the drug. It was not long before her heart stopped. The girl died in her mother’s arms two days later. Along with the narcotics, she had a hospital-acquired infection and was severely dehydrated.

Discussion Questions

- What factors contributed to the girl’s death?

- Consider the power structures in this case. What power did the nurse have? How about the girl’s mother? What could the physicians and nurses have done to give the mother more power to affect her daughter’s care?

- How could the girl’s death have been prevented? What measures would you put in place to make sure this did not happen to another patient?

REFERENCES

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). 2020. “About CAHPS.” Reviewed March. www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/index.html.

———. 2018. “Understanding Quality Measurement.” Reviewed October. www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/chtoolbx/understand/index.html.

Al-Abri, R., and A. Al-Balushi. 2014. “Patient Satisfaction Survey as a Tool Towards Quality Improvement.” Oman Medical Journal 29 (1): 3–7.

Aluko, Y. 2017. “The Delicate Balance Between Cost and Quality in Value-Based Healthcare.” Becker’s Healthcare. Published February 20. www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/the-delicate-balance-between-cost-and-quality-in-value-based-healthcare.html.

American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). 2016. “Value-Based Payment.” Accessed June 16, 2020. www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/value-based-payment.html.

Bailey, Z., N. Krieger, M. Agenor, J. Graves, N. Linos, and M. Bassett. 2017. “Structural Racism and Health Inequities in the USA: Evidence and Interventions.” The Lancet 389 (10077): 1453–63.

Batalden, M., P. Batalden, P. Margolis, M. Seid, G. Armstrong, L. Opipari-Arrigan, and H. Hartung. 2015. “Coproduction of Healthcare Services.” BMJ Quality & Safety 25 (7): 509–17.

Burgener, A. 2017. “Enhancing Communication to Improve Patient Safety and to Increase Patient Satisfaction.” Health Care Manager 36 (3): 238–43.

Carroll, A. 2015. “To Be Sued Less, Doctors Should Consider Talking to Patients More.” New York Times. Published June 1. www.nytimes.com/2015/06/02/upshot/to-be-sued-less-doctors-should-talk-to-patients-more.html.

Castro, D., B. Miller, and A. Nager. 2014. “Unlocking the Potential of Physician-to-Patient Telehealth Services.” Information technology & Innovation Foundation. Published May 12. https://itif.org/publications/2014/05/12/unlocking-potential-physician-patient-telehealth-services.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). 2020a. “Electronic Clinical Quality Measures Basics.” Updated May 21. www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/ClinicalQualityMeasures.html.

———. 2020b. “What Are the Value-Based Programs?” Updated January 6. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs.html.

———. 2019a. “CMS-Approved Accrediting Organizations Contacts for Prospective Clients.” Accessed June 16, 2020. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Accrediting-Organization-Contacts-for-Prospective-Clients-.pdf.

———. 2019b. “Quality Initiatives—General Information.” Updated November 17. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/index.html.

Chassin, M. R., and E. C. Becher. 2002. “The Wrong Patient.” Annals of Internal Medicine. Published June 4. http://annals.org/aim/fullarticle/715318/wrong-patient.

Chassin, M. R., and R. W. Galvin. 1998. “The Urgent Need to Improve Healthcare Quality.” JAMA 280 (11): 1000–1005.

Christensen, C. M., R. M. J. Bohmer, and J. Kenagy. 2000. “Will Disruptive Innovations Cure Healthcare?” Harvard Business Review 78 (5): 102–12.

Christensen, C. M., and M. E. Raynor. 2003. The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Damberg, C., M. Sorbero, S. Lovejoy, G. Martsolf, L. Raaen, and D. Mandel. 2014. “Measuring Success in Healthcare Value-Based Purchasing Programs: Findings from an Environmental Scan, Literature Review, and Expert Panel Discussions.” Rand Health Quarterly 4 (3): 9.

Deloitte. 2017. Transforming into a High Reliability Organization in Health Care. Accessed June 16, 2020. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/life-sciences-health-care/us-lshc-health-care-high-reliability-organization.pdf.

Dickman, S. L., D. U. Himmelstein, and S. Woolhandler. 2017. “Inequality and the Health-Care System in the USA.” The Lancet 389: 1431–41.

Flavin, B. 2018. “7 Critical Factors That Impact Patient Experience.” Rasmussen College Health Sciences Blog. Published July 10. www.rasmussen.edu/degrees/health-sciences/blog/patient-experience-factors/.

Gaffney, A., and D. McCormick. 2017. “The Affordable Care Act: Implications for Health-Care Equity.” The Lancet 389: 1442–52.

Gift, R. G., and D. Mosel. 1994. Benchmarking in Healthcare. Chicago: American Hospital Publishing.

Godfrey, T. 2012. “What Is the Iron Triangle of Healthcare?” Penn Square Post. Published March 3. http://pennsquarepost.com/what-is-the-iron-triangle-of-health-care/.

Hughes, R. G., ed. 2008. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses, Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Huntington, B., and N. Kuhn. 2003. “Communication Gaffes: A Root Cause of Malpractice Claims.” Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 16 (2): 157–61.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). 2020a. “About Us.” Accessed June 16. www.ihi.org/about/Pages/default.aspx.

———. 2020b. “How to Improve.” Accessed June 16. www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx.

———. 2020c. “The IHI Triple Aim Initiative: Better Care for Individuals, Better Health for Populations, and Lower Per Capita Costs.” Accessed June 16. www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx.

———. 2017. “Quality Improvement Essentials Toolkit.” Accessed June 16, 2020. www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/Quality-Improvement-Essentials-Toolkit.aspx.

Institute of Medicine. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

———. 1999. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

———. 1996. America’s Health in Transition: Protecting and Improving Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Jha, B. 2018. “Accreditation, Quality, and Making Hospital Care Better.” JAMA 320 (23): 2410–11.

Johns Hopkins Medicine. 2016. “Study Suggests Medical Errors Now Third Leading Cause of Death in the U.S.” News release, May 3. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/study_suggests_medical_errors_now_third_leading_cause_of_death_in_the_us.

The Joint Commission. 2020a. “About the Joint Commission.” Accessed June 16. www.jointcommission.org/about_us/about_the_joint_commission_main.aspx.

———. 2020b. “High Reliability in Health Care Is Possible.” Accessed June 16. www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/high-reliability-in-health-care.

———. 2019a. “Quality and Safety: Sentinel Events Statistics Released for 2018.” Accessed June 17, 2020. www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sentinel-event-data-summary/.

———. 2019b. “2019 National Patient Safety Goals.” Accessed June 16, 2020. www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2019_HAP_NPSGs_final2.pdf.

———. 2013. “Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospital 2013: Sentinel Events.” Published January. www.jointcommission.org/-/media/deprecated-unorganized/imported-assets/tjc/system-folders/topics-library/camh_2012_update2_24_sepdf.pdf.

Kanbanize. 2019. “7 Wastes of Lean: How to Optimize Resources.” Accessed June 16, 2020. https://kanbanize.com/lean-management/value-waste/7-wastes-of-lean/.

Kaplan, M. 2016. “Co-production: A New Lens on Patient-Centered Care.” Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Published April 1. www.ihi.org/communities/blogs/co-production-a-new-lens-on-patient-centered-care.

Kissick, W. 1994. Medicine’s Dilemmas: Infinite Needs Versus Finite Resources. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lohr, K. N., ed. 1990. Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Medicare.gov. 2020. “Survey of Patients’ Experiences (HCAHPS).” Accessed June 16. www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/about/survey-patients-experience.html.

Monk, J. 2002. “How a Hospital Failed a Boy Who Didn’t Have to Die.” The State (Columbia, SO), June 16, A1, A8–9.

National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). 2020. “HEDIS and Performance Measurement.” Accessed June 16. www.ncqa.org/hedis/.

National Quality Forum (NQF). 2020. “List of SREs.” Accessed June 17. www.qualityforum.org/Topics/SREs/List_of_SREs.aspx.

Neilson, S. 2019. “The Gap Between Rich and Poor Americans’ Health Is Widening.” National Public Radio. Published June 28. www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/06/28/736938334/the-gap-between-rich-and-poor-americans-health-is-widening.

O’Daniel, M., and A. Rosenstein. 2008. “Professional Communication and Team Collaboration.” In Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses, edited by R. G. Hughes, chapter 3. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP). 2014. National Action Plan for Adverse Drug Event Prevention. Accessed June 16, 2020. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/ADE-Action-Plan-508c.pdf.

Regula, C., J. Miller, and D. Mauger. 2007. “Quality of Care from a Patient’s Perspective.” JAMA Dermatology 143 (12): 1589–1603.

Rogers, S., A. Gawande, M. Kwann, A. Puopolo, C. Yoon, T. Brennan, and D. Studdert. 2006. “Analysis of Surgical Errors in Closed Malpractice Claims at 4 Liability Insurers.” Surgery 140 (1): 25–33.

Saver, B., S. Martin, R. Adler, L. Candib, K. Deligiannidis, J. Golding, D. Mulling, M. Roberts, and S. Topolski. 2015. “Care That Matters: Quality Measurement and Health Care.” PLOS Medicine 12(11): e1001902.

Schneider, E., D. Sarnak, D. Squires, A. Shah, and M. Doty. 2017. “Mirror, Mirror 2017: International Comparison Reflects Flaws and Opportunities for Better U.S. Healthcare.” Commonwealth Fund. Published July. https://interactives.commonwealthfund.org/2017/july/mirror-mirror.

Schuster, M., E. McGlynn, and R. Brook. 2005. “How Good Is the Quality of Healthcare in the United States?” Milbank Quarterly 83 (4): 843–95.

Spencer, C., D. Gaskin, and E. Roberts. 2013. “The Quality of Care Delivered to Patients Within the Same Hospital Varies by Insurance Type.” Health Affairs 32 (10): 1731–39.

Sutcliffe, K., E. Lewton, and M. Rosenthal. 2004. “Communication Failures: An Insidious Contributor to Medical Mishaps.” Academy Medicine 79 (2): 186–94.

W. Edwards Deming Institute. 2020. “PDSA Cycle.” Accessed June 16. https://deming.org/explore/p-d-s-a.

Wallace, E., J. Lowry, S. M. Smith, and T. Fahey. 2013. “The Epidemiology of Malpractice Claims in Primary Care: A Systematic Review.” BMJ Open 3(6): e002929.

Weiss, A., W. Freeman, K. Heslin, and M. Barrett. 2018. “Adverse Drug Events in U.S. Hospitals, 2010 versus 2014.” Statistical Brief 234, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Published January. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb234-Adverse-Drug-Events.jsp.

Zimlich, R. 2017. “Value-Based Payment Update: Where We Are and Who Is Most Successful.” Managed Healthcare Executive. Published November 16. http://managedhealthcareexecutive.modernmedicine.com/managed-healthcare-executive/news/value-based-payment-update-where-we-are-and-who-most-successful.