CHAPTER 1

THE HISTORY OF US HEALTHCARE AND THE DEMOGRAPHICS OF DISEASE

The delivery and funding of healthcare in the United States are complex and uncertain for many people. In fact, Americans experience vastly different levels of care, depending on their age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geographic location. These differences are products of the convoluted development of healthcare in the United States. Today, whether healthcare is a right or a privilege for those who can afford it is one of the most pressing questions in American society.

“Is healthcare a privilege or a right? That may be the most contentious question in the whole healthcare debate. When he was president, George W. Bush felt the need to address this question by saying we have universal care in this country because everyone can ‘just go to an emergency room.’ But there is a big difference between going to the ER because you have no insurance versus having health insurance that allows you to go to a doctor or clinic of your choice when you are sick or think you might have a problem. In general, people with health insurance tend to get help earlier, when it is less costly and more effective. In fact, one Harvard study suggests that 45,000 Americans die prematurely every year because they lack health insurance. . . . There is no such thing as an American healthcare system. . . . What we have instead is a hodgepodge of private and public insurance plans with cracks between them” (Johnson 2017).

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

Identify the key historical events that shaped the US healthcare system.

Identify the key historical events that shaped the US healthcare system.

Explain how healthcare access, quality, and cost are interrelated.

Explain how healthcare access, quality, and cost are interrelated.

Discuss how age and chronic disease affect healthcare use, cost, and access.

Discuss how age and chronic disease affect healthcare use, cost, and access.

Understand how the diversity of the US population influences healthcare.

Understand how the diversity of the US population influences healthcare.

Explain why healthcare costs vary so widely in the United States.

Explain why healthcare costs vary so widely in the United States.

Identify the factors that affect life expectancy and explain why life expectancy in the United States has declined.

Identify the factors that affect life expectancy and explain why life expectancy in the United States has declined.

Understand the dangers of new and emerging diseases.

Understand the dangers of new and emerging diseases.

THE HISTORY OF THE US HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

Healthcare in the United States and elsewhere in the world was primitive and lacked sophisticated technology until the beginning of the twentieth century. Before then, the training and practice of medicine was not standardized, and most practitioners were unlicensed. Between 1760 and 1850, some educated doctors sought to establish special recognition for their profession and organized medical schools. However, US state legislatures consistently rejected the need to professionalize medicine, and many states even eliminated what little medical licensure existed. During this time, lay practitioners with little or no formal medical education proliferated, many of whom practiced herbal and folk remedies. Some physicians even denigrated the value of medical training, suggesting that “professional knowledge and training were unneeded in treating most diseases” (Starr 1982, 33).

American physicians initially sought to model their profession after England’s Royal Society of Medicine, which set physicians apart as an elite order. Physicians did not physically examine patients but primarily recommended courses of treatment. Physicians at first were distinguished from surgeons, who came from the same guild as barbers and primarily performed manual tasks, such as draining wounds and pulling teeth. Another important group in the medical establishment was apothecaries, who prescribed and charged for medicines, which they made by hand. By the late 1700s, these roles began to converge, with physicians both examining and treating patients as well as creating and dispensing their own medications. Few, however, had any formal training: At this time, only about 200 of 4,000 physicians in the United States held medical degrees. The rest were lay personnel, who were inconsistently trained (at best) in areas such as childbirth, bone setting, cancers, inoculations, and abortions (Starr 1982).

By the early 1800s, medical schools were being established in the United States. By the mid-1850s, 42 US medical schools were in operation. Most were located in rural areas that lacked hospitals and clinical facilities. A degree from such a school was generally considered sufficient training to practice medicine without state licensure. Hospitals also began to emerge during this time. Some communities opened hospitals and “pesthouses” to isolate those with contagious diseases, and every state had at least one mental asylum. By 1850, the number of physicians had increased eightfold, to about 40,000.

Medical care typically was provided on credit. Physicians billed their patients directly, but patients often paid only a fraction of their charges, or they provided goods in kind or bartered for the medical services they received. The increase in the number of physicians saturated many markets. As a result, many doctors chose to relocate to rural areas, while others took second jobs to make a living.

The lack of transportation infrastructure was a major factor that constrained the use of medical care. Most of the US population lived in rural areas, where transportation was relatively inaccessible. In 1850, 84.6 percent of the US population was rural; by 1900, this number had decreased to 60.4 percent (US Census Bureau 1993). In both rural and urban areas, most physician consultations took place in patients’ homes rather than in offices, and physicians generally charged according to the distance they had to travel. Before the invention of the telephone, families had to travel to find a doctor; because most doctors were out visiting patients, they were difficult to locate. As a result, families in rural areas sought a doctor only for very serious conditions. The advent of railroads and canals, followed later by the automobile and the telephone, facilitated greater access to care by lowering the cost and time required to obtain healthcare services (Starr 1982).

In the early 1800s, Americans perceived little need for hospitals, as most people received healthcare services in their homes. The few hospitals that did exist generally provided poor and dirty conditions and were primarily designed to isolate the sick from their communities. Hospitals were most often established by religious and charitable organizations as holding institutions for the sick, rather than as places for curing illness. Mental asylums, likewise, were created as holding facilities for the mentally ill. These places were frequently dangerous, however, and most patients felt safer at home (see sidebar).

THE ORIGIN OF NEW YORK CITY’S BELLEVUE HOSPITAL

THE ORIGIN OF NEW YORK CITY’S BELLEVUE HOSPITAL

In 1736, the New York Almshouse was founded as a pest and death house for people suffering from communicable diseases such as cholera and yellow fever. The poor and the mentally ill were treated with experimental care there—often without the use of anesthesia. For those who could not afford a private doctor, the almshouse sometimes was their only choice for medical care. Later, the facility was used as a “dumping ground” for many patients who were terminally ill or otherwise unwanted.

Because of the diversity of cases treated there, the Almshouse—renamed Bellevue Hospital in 1824—provided an ideal setting for clinical training and research. Training for physicians as interns began there in 1856, and the first professional nursing school opened at Bellevue in 1873. In the twentieth century, the hospital continued to improve its quality of care and professionalization, and it become known as one of the premier training and treatment centers in the United States (Howe 2016).

Advances in transportation and technology made the centralization of patients into hospitals and physician offices more practical. Both the automobile and the telephone allowed patients to more easily schedule and access medical care. Physicians could practice in their offices, rather than travel to patients’ homes. This concentration of practice allowed greater efficiencies of scale for medical personnel, as physicians could see greater numbers of patients in a day. This practice also gave rise to specialization. Still, however, few physicians in the 1800s could become wealthy practicing medicine.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, most states had implemented medical licensure for physicians. Initially, licensure laws allowed anyone graduating from any operating medical school to practice medicine. Gradually, these laws changed to allow only those who graduated from recognized, accredited medical schools to practice medicine. These stricter regulations led many poorly trained and marginally competent physicians to stop practicing.

The rapid expansion of the American Medical Association (AMA), along with local medical societies, had a powerful influence on physician training by organizing and standardizing it throughout the country. In the early 1900s, the AMA helped reform medical school education, requiring a minimum number of years of high school education and medical training, in addition to a test for licensure. The AMA also began to grade medical schools. Ultimately, the AMA facilitated the greatest change in medical school education by sponsoring a research group from the Carnegie Foundation that examined and recommended changes to medical training. The issuance of the so-called Flexner Report (named for its lead author, Abraham Flexner) in 1910 resulted in the closure of about 35 percent of existing medical schools by 1915 and decreased the number of medical school graduates from 5,440 to 3,536 (Starr 1982, 120). The higher standards may have improved the quality of practitioners, but they also increased the cost of medical education and resulted in a greater concentration of physicians in urban settings, which exacerbated the physician shortages in rural and poor areas.

Hospitals also benefited from the recommendations of the Flexner Report and the changes it spurred in medical education. More and more physicians began to train in hospitals. In 1902, about 50 percent of physicians trained in hospitals; by 1912, the share had risen to almost 80 percent (Starr 1982, 124). In addition, advances in bacteriology and antibiotics dramatically expanded the range of surgical operations. This, coupled with developments in diagnostic testing that required expensive equipment, reinforced the importance of medical practice in hospitals. Patients began to use hospitals for more complicated medical treatments, rather than simply for isolation for acute illnesses.

As healthcare education and practice moved toward standardization in the early twentieth century, the structures of hospitals and the roles of healthcare professionals evolved as well. The roles of physicians and nurses were defined more clearly, especially as these professionals began to specialize in areas such as surgery, children, adult medicine, and so on. Nonphysician providers, such as pharmacists, laboratory assistants, and dieticians, were trained to take over some of the tasks that traditionally had been done by physicians. Advances in surgery, as a result of the discovery of effective anesthetics and antibiotics, drew many physicians to hospitals. Doctors began treating patients in these facilities and relying on them for much of their income. However, because physicians typically did not own the facilities, nor were they employed or paid by hospitals, they retained a high degree of autonomy and could bill patients directly for their services.

Gradually, hospitals shifted from organizations funded by charities to institutions financed by patients, insurance companies, and employers. Hospitals became one of the main employers in the United States and centers for the practice of medicine. From their humble beginnings, hospitals have grown into a mammoth industry, now accounting for $1.1 trillion in healthcare spending each year in the United States (AHA 2020).

The same developments that shaped the delivery of healthcare also influenced the pharmaceutical industry. Prior to the twentieth century, the quality and composition of drugs sold to the public were unreliable. Many so-called patent medicines were composed of proprietary, or secret, compounds. The pharmaceutical industry emerged as a result of efforts by the AMA to make physicians the preferred prescribers of drugs as well as investigative journalism that exposed dangerous, unregulated drugs. Many of these products, as seen in exhibit 1.1, contained toxic, addictive, or dangerous ingredients. By the early 1900s, the public was being encouraged to obtain their medications from doctors (see sidebar). Further, new discoveries, such as vaccines and antibiotics, bolstered the reputation of the nascent industry.

EXHIBIT 1.1 Dangerous Patent Medicines in the 1800s and Early 1900s

Details

The details of the list are as follows:

- Norodin: A methamphetamine product that promised to dispel the shadows of depression.

- Laudanum: An opium mix used to treat everything from meningitis to yellow fever.

- Cigares de Joy: Tobacco to treat asthma.

- Quaalude 300: A sedative used to treat insomnia.

- Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup: A morphine concoction given to teething children.

- Kimball White Pine and Tar Cough Syrup: A chloroform syrup for colds and bronchitis.

- Bayer Heroin Hydrochloride: A heroin product used as a cough suppressant.

- Cocaine Toothache Drops: A cocaine product for children’s toothaches.

Source: Amondson (2013).

THE MOVEMENT TOWARD PRESCRIBED MEDICATIONS

THE MOVEMENT TOWARD PRESCRIBED MEDICATIONS

In support of physician-prescribed medications, Collier’s magazine published this perspective on patent medicines in 1906: “Don’t dose yourself with secret patent medicines, almost all of which are Frauds and Humbugs. When sick consult a doctor and take his prescription: It is the only sensible way and you’ll find it cheaper in the end” (Turow 2010, 22).

By the mid-twentieth century, laws had been passed that outlined the formal approval process for drugs and designated which drugs required written prescriptions from physicians and which could be sold “over the counter” (Rahalkar 2012). Since then, the pharmaceutical industry has become a trillion-dollar global industry. North America alone accounts for almost half (48.9 percent) of all prescription costs (Mikulic 2019). Almost 300,000 pharmacists are now working in the United States, filling almost 4.4 billion prescriptions annually (Shahbandeh 2019; Venosa 2016).

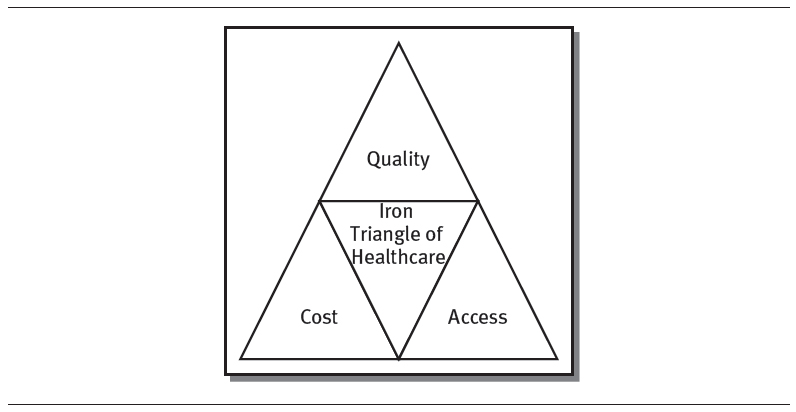

THE “IRON TRIANGLE” OF HEALTHCARE

As medical technology has advanced, governments around the world have struggled to balance three dimensions of healthcare: providing adequate access to care, containing the cost of care, and improving the quality of care. As shown in exhibit 1.2, access, cost, and quality make up the Iron Triangle of Healthcare.

EXHIBIT 1.2 The Iron Triangle of Healthcare

Details

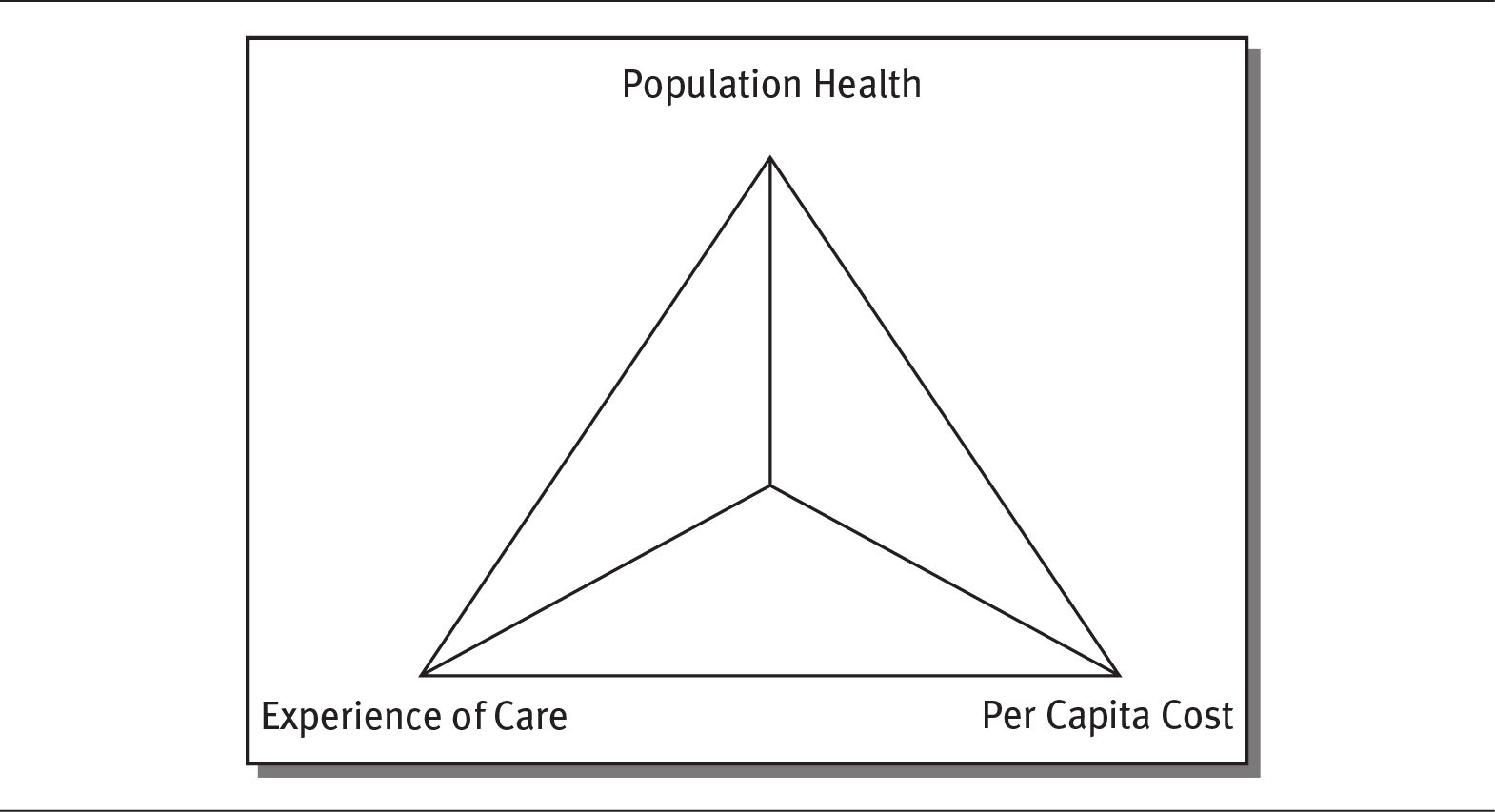

However, others believe that all three of the dimensions of care can be pursued concurrently (IHI 2020). They propose that achieving access, cost, and quality can be accomplished by improving healthcare efficiencies, changing the way healthcare is paid for, and fostering disruptive innovations (Berwick, Nolan, and Whittington 2008).

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), a national healthcare organization that is focused on improving healthcare in the United States, has proposed a modified version of the Iron Triangle called the Triple Aim, which highlights the interdependencies of population health, quality, and cost. The Triple Aim was developed to help healthcare organizations focus on these three dimensions simultaneously. The IHI does not regard the three components of the Triple Aim as independent of one another; rather, it recommends that healthcare organizations pursue a balanced approach to reducing cost while increasing quality among at-risk populations and addressing communities’ health concerns (Berwick, Nolan, and Whittington 2008). As shown in exhibit 1.3, the Triple Aim differs slightly from the Iron Triangle of Healthcare. The Triple Aim focuses on three factors:

EXHIBIT 1.3 The IHI Triple Aim

Details

The concept of the Iron Triangle was introduced by William Kissick in his 1994 book Medicine’s Dilemmas: Infinite Needs Versus Finite Resources. Kissick, a physician, public health official, and scholar, argued that the three dimensions of access, cost, and quality necessarily compete with one another—that is, a change in one factor must have an impact on the others. For instance, increasing the quality of care requires increasing costs, because quality requires the allocation of more resources, including people and equipment, to improve clinical processes and outcomes. Likewise, increasing access to care requires providing more services at more locations, which also increases costs. Conversely, cutting costs, which might mean limiting resources or minimizing operational locations, hours, equipment, and clinicians, decreases quality and access. This trade-off is a key principle of the Iron Triangle: Healthcare organizations can improve only two of the three dimensions while sacrificing the third. Many, like Kissick, argue that these trade-offs are inevitable.

Population health. Population health centers on improving the health of entire populations. Identifying populations to work with, especially at-risk populations, is essential to addressing the Triple Aim.

Population health. Population health centers on improving the health of entire populations. Identifying populations to work with, especially at-risk populations, is essential to addressing the Triple Aim.

Experience of care. This component includes quality of care but is broken down into two measures: patient satisfaction and clinical quality of care.

Experience of care. This component includes quality of care but is broken down into two measures: patient satisfaction and clinical quality of care.

Per capita cost. This factor refines healthcare costs by measuring them on a per capita, or per person, basis. The Triple Aim seeks to lower, or at least maintain, actual costs for individuals while improving care outcomes (Galvin 2018).

Per capita cost. This factor refines healthcare costs by measuring them on a per capita, or per person, basis. The Triple Aim seeks to lower, or at least maintain, actual costs for individuals while improving care outcomes (Galvin 2018).

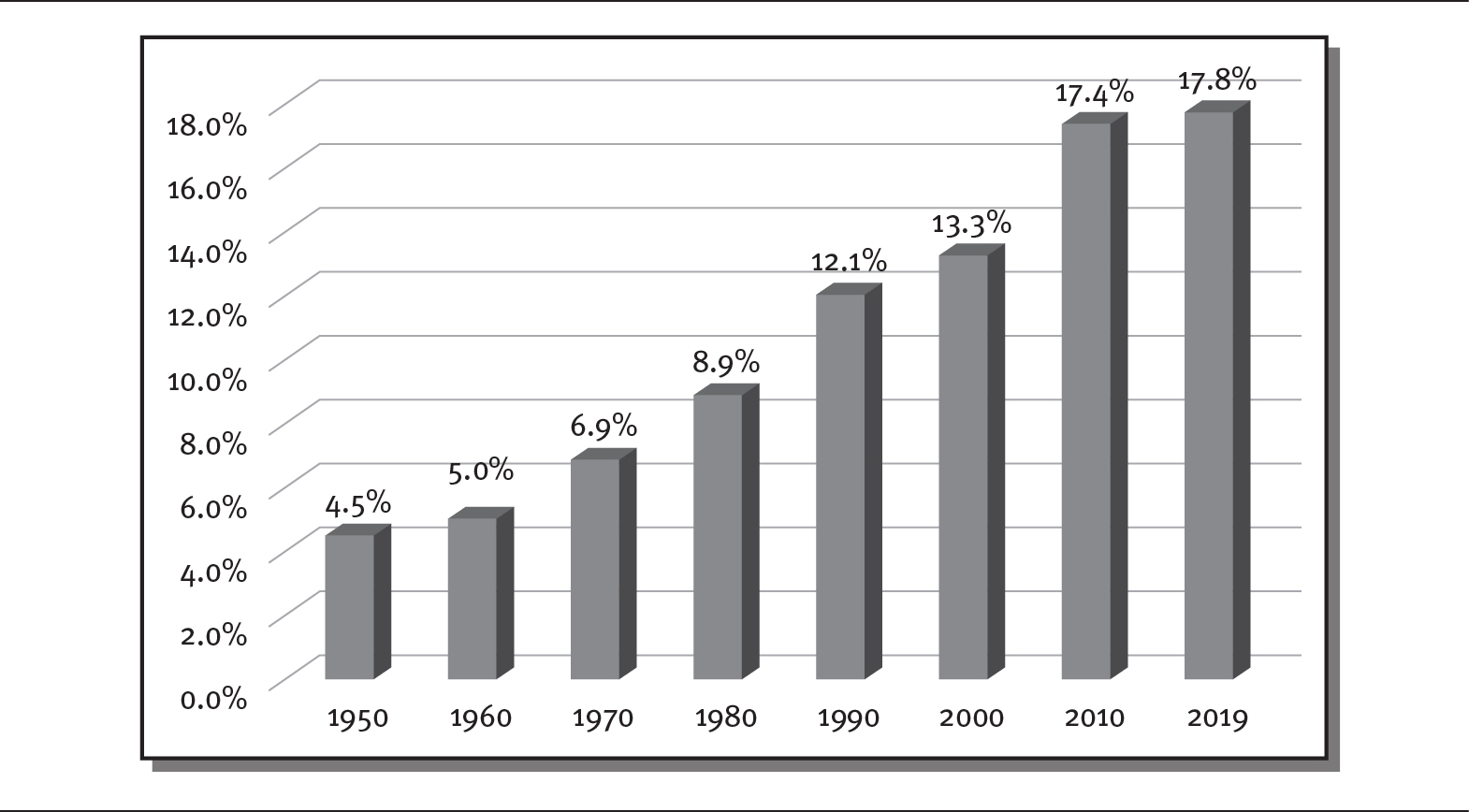

The US healthcare system has struggled to balance the three dimensions of access, quality, and cost. Healthcare spending has risen steadily over the last century. As shown in exhibit 1.4, by the middle of the twentieth century, healthcare spending accounted for 4.5 percent of US gross domestic product (GDP). By 1980, this figure had reached 8.9 percent, and by 2018, it stood at 17.8 percent (Statista 2019, 2020). Much of the increase in healthcare spending is attributable to increases in the price and intensity of healthcare, higher rates of chronic diseases, and higher expenditures on pharmaceuticals (Scutti 2017).

EXHIBIT 1.4 US National Healthcare Expenditures as a Percentage of GDP, 1950–2019

Details

The x-axis shows the years from 1950 to 2019 in increments of 10 years. The y-axis shows percentage of GDP from 0.0 to 18.0 in increments of 2.0 percentage. The details of healthcare expenditure as percentage are as follows:

- 1950: 4.5

- 1960: 5.0

- 1970: 6.9

- 1980: 8.9

- 1990: 12.1

- 2000: 13.3

- 2010: 17.4

- 2019: 17.8.

Source: Data from Statista (2019, 2020).

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 sought to address the three aims of the Iron Triangle by simultaneously improving healthcare access and quality while reducing the cost of care. However, the expansion of access and quality came at a cost. The implementation of the ACA increased the costs of compliance and thus contributed to a rise in healthcare costs and insurance premiums, as predicted by the Iron Triangle of Healthcare (Godfrey 2012; Manchikanti et al. 2017; Weiner, Marks, and Pauly 2017).

Dr. Aaron Carroll (2012), a pediatrician and healthcare researcher at Indiana University, summarized the trade-off in this way:

I can make the healthcare system cheaper (improve cost), but that can happen only if I reduce access in some way or reduce quality. I can improve quality, but that will either result in increased costs or reduced access. And of course, I can increase access . . . but that will either cost a lot of money (it does) or result in reduced quality. . . . The lesson of the iron triangle is that there are inherent trade-offs in health policy.

Healthcare remains a top concern for Americans. A 2019 survey showed that healthcare was the top concern for 36 percent of the US population, followed by the economy at 26 percent. In addition, 67 percent of respondents agreed that the US healthcare system is broken or not working well (Cannon 2019). Americans perceive the quality and cost of healthcare as the most significant concerns. (See chapter 10 for an in-depth discussion of efforts to improve healthcare quality in the United States.)

Escalating healthcare costs in the United States have affected both access to and the quality of care. As the Institute of Medicine (2001, 1) stated two decades ago, “The U.S. healthcare delivery system does not provide consistent, high-quality medical care to all people. . . . Healthcare harms patients too frequently and routinely fails to deliver its potential benefits.” Yet 20 years later, healthcare disparities persist, which have direct effects on Americans’ life expectancy. As a National Academy of Medicine report noted more recently, “Despite the magnitude of national spending, unacceptable disparities still exist in the health experiences of different population groups, and, for certain groups, those disparities are increasing to the point that life spans are actually decreasing” (Whicher et al. 2018, xi)

Employers, politicians, insurance companies, and providers continue to struggle with the Iron Triangle of Healthcare and achieving the Triple Aim of controlling costs without unreasonably affecting quality and access. Nevertheless, increasing costs have forced many Americans to give up their health insurance (see sidebar), leaving them vulnerable to higher healthcare expenses and, potentially, decreased access to and quality of care.

AGING AND CHRONIC DISEASE

Statistics show a direct correlation between age and the amount of healthcare an individual uses. As in most industrialized nations, the population of the United States is aging rapidly. Demographers estimate that by 2030, about 20 percent of the US population will be over the age of 65, an increase from 12 percent in 2000. Between 2000 and 2016, the median age of the US population rose 2.5 years, from 35.3 to 37.9 (Chappell 2017).

Aging puts people at greater risk of developing a chronic disease, which, in turn, increases the use, cost, and intensity of healthcare. In 1900, infectious diseases such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, and gastrointestinal infections were the leading causes of death (Statista 2020). The twentieth century saw a major shift as chronic diseases, such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes, became the leading causes of death in the United States (Rutledge et al. 2018).

DEBATE TIME A Retiree’s Difficult Decision

DEBATE TIME A Retiree’s Difficult Decision

In 2018, Dana Farrell, a 54-year-old retired social worker, had to make a difficult decision. Her monthly health insurance premiums had jumped to about $600 per month. Even with coverage, she still had to pay $80 per doctor visit. This expense, coupled with her many other bills and limited savings, made her health insurance unaffordable, so she made the difficult decision to drop it. Dana was nervous about not having coverage. Although she hoped she would not get sick or have an accident, she felt she simply did not have a choice (Bazar 2018).

Why do people choose not to have health insurance? What happens when people drop their health insurance? What options might a person have to retain some form of health insurance?

Today, as shown in exhibit 1.5, about 60 percent of adults in the United States have one or more chronic diseases, and 40 percent have two or more. The most prevalent chronic diseases are heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Furthermore, 40 percent of all adults in the United States are obese, and more than one-third of adults who are obese have diabetes, which is the leading cause of kidney failure, limb amputations, and blindness. Tobacco use, poor nutrition, lack of physical activity, and excessive alcohol use contribute to many of these chronic diseases (CDC 2020c).

EXHIBIT 1.5 Most Prevalent Chronic Diseases Among Americans

Details

The poster reads as:

Six in ten adults in the US have a chronic disease and four in ten adults have two or more.

A pictorial representation of diseases at the footer of the poster shows heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease.

Source: CDC (2020c).

Among the elderly, those who are sicker spend much more money on healthcare. In 2016, 1 percent of the elderly accounted for 12 percent of healthcare costs, and 10 percent of the elderly accounted for 50 percent of healthcare expenses. People aged 65 and older make up 13 percent of the US population, but they account for 34 percent of total healthcare spending—$18,424 per person—and spend three times more, on average, than adults under age 65 (Sawyer and Claxton 2019). Healthcare use—and hence cost—continues to rise with age: Healthcare spending for an 85-year-old, for example, is 2.5 times more than that of a 66-year-old, and for a 95-year-old, it is three times more (Neuman et al. 2015). A couple who retired in 2019 at age 65 can expect to spend $285,000 on healthcare during their retirement (O’Brien 2019).

DIVERSITY AND HEALTHCARE

As the United States becomes a more diverse country, its healthcare needs are changing as well. Although non-Hispanic/Latino whites still make up a majority of the US population, accounting for 60.4 percent (198 million people), Hispanics/Latinos have become the second-largest population, accounting for 18.3 percent (60 million), and Blacks and African Americans are the third-largest population, with 13.4 percent (44 million) (Chappell 2017; US Census Bureau 2019).

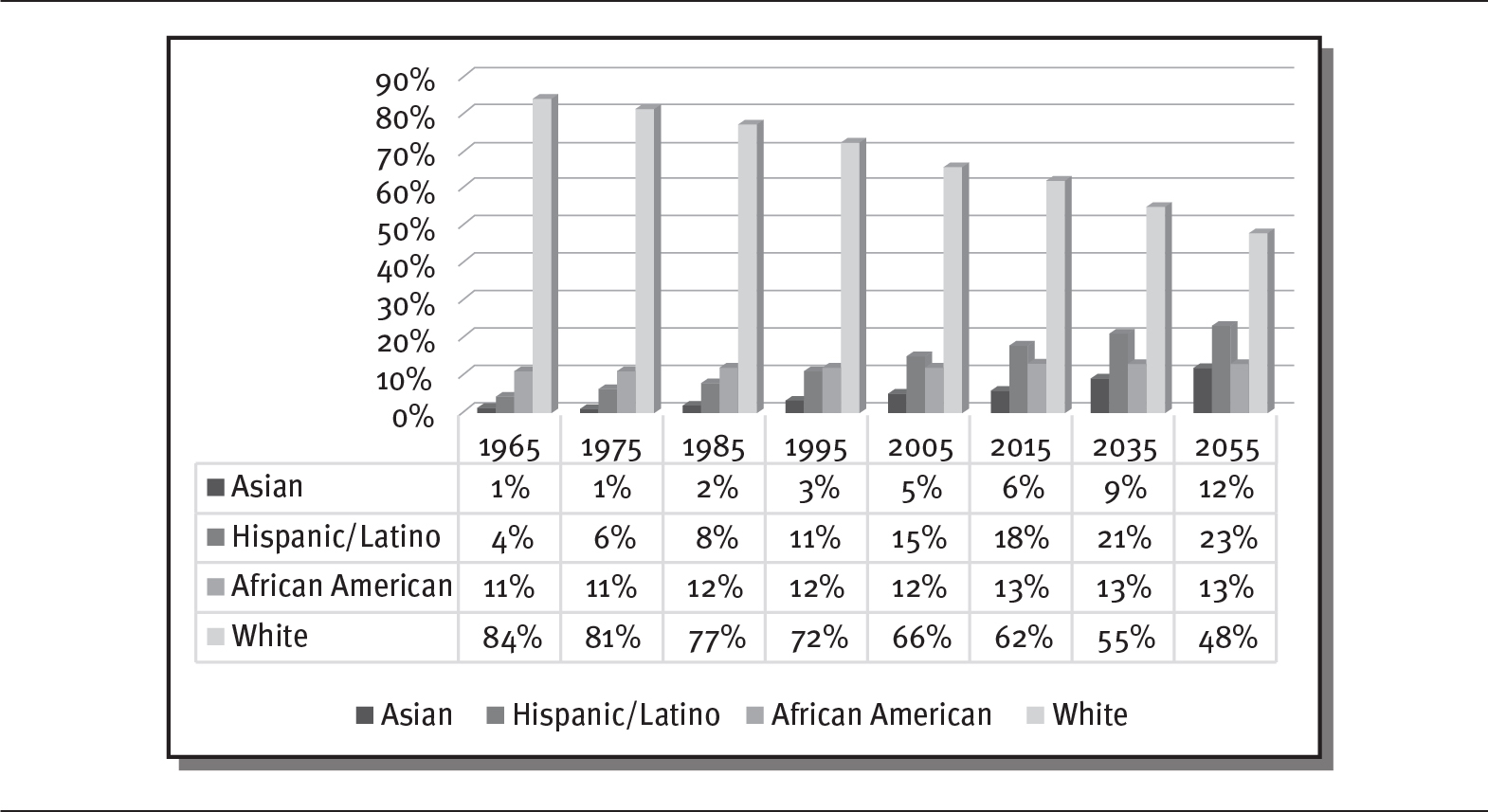

The composition of the US population is projected to continue these trends over the next several decades, as shown in exhibit 1.6. Demographers forecast that by 2055, the United States will not have a single racial or ethnic majority, as the white population is expected to shrink to 48 percent of the total population, while Hispanics/Latinos are projected to make up nearly one-quarter of the population (Cohn and Caumont 2016).

EXHIBIT 1.6 Historical and Projected Racial/Ethnic Composition of the US Population, 1965–2055

Details

The x-axis shows years from 1965 to 2055. The y-axis shows percentage from 0 to 90 in increments of 10. The clustered bars depict Asian, Hispanic or Latino, African American, and White. The percentage details are as follows:

- 1965: Asian, 1; Hispanic or Latino, 4; African American, 11; and White, 84.

- 1975: Asian, 1; Hispanic or Latino, 6; African American, 11; and White, 81.

- 1985: Asian, 2; Hispanic or Latino, 8; African American, 12; and White, 77.

- 1995: Asian, 3; Hispanic or Latino, 11; African American, 12; and White, 72.

- 2005: Asian, 5; Hispanic or Latino, 15; African American, 12; and White, 66.

- 2015: Asian, 6; Hispanic or Latino, 18; African American, 13; and White, 62.

- 2035: Asian, 9; Hispanic or Latino, 21; African American, 13; and White, 55.

- 2055: Asian, 12; Hispanic or Latino, 23; African American, 13; and White, 48.

Source: Data from Pew Research Center (2015).

Historically, people of African American and Hispanic/Latino backgrounds in the United States have experienced greater difficulty accessing healthcare services and health insurance than whites, and they have tended to receive lower-quality care and experience worse healthcare outcomes (Hayes et al. 2017). These outcomes are attributable to two factors: These groups tend to have lower incomes compared with whites, and they are more likely to work for businesses that do not provide health insurance. Both of these factors limit access to healthcare, which leads to untreated health conditions and exacerbates health problems.

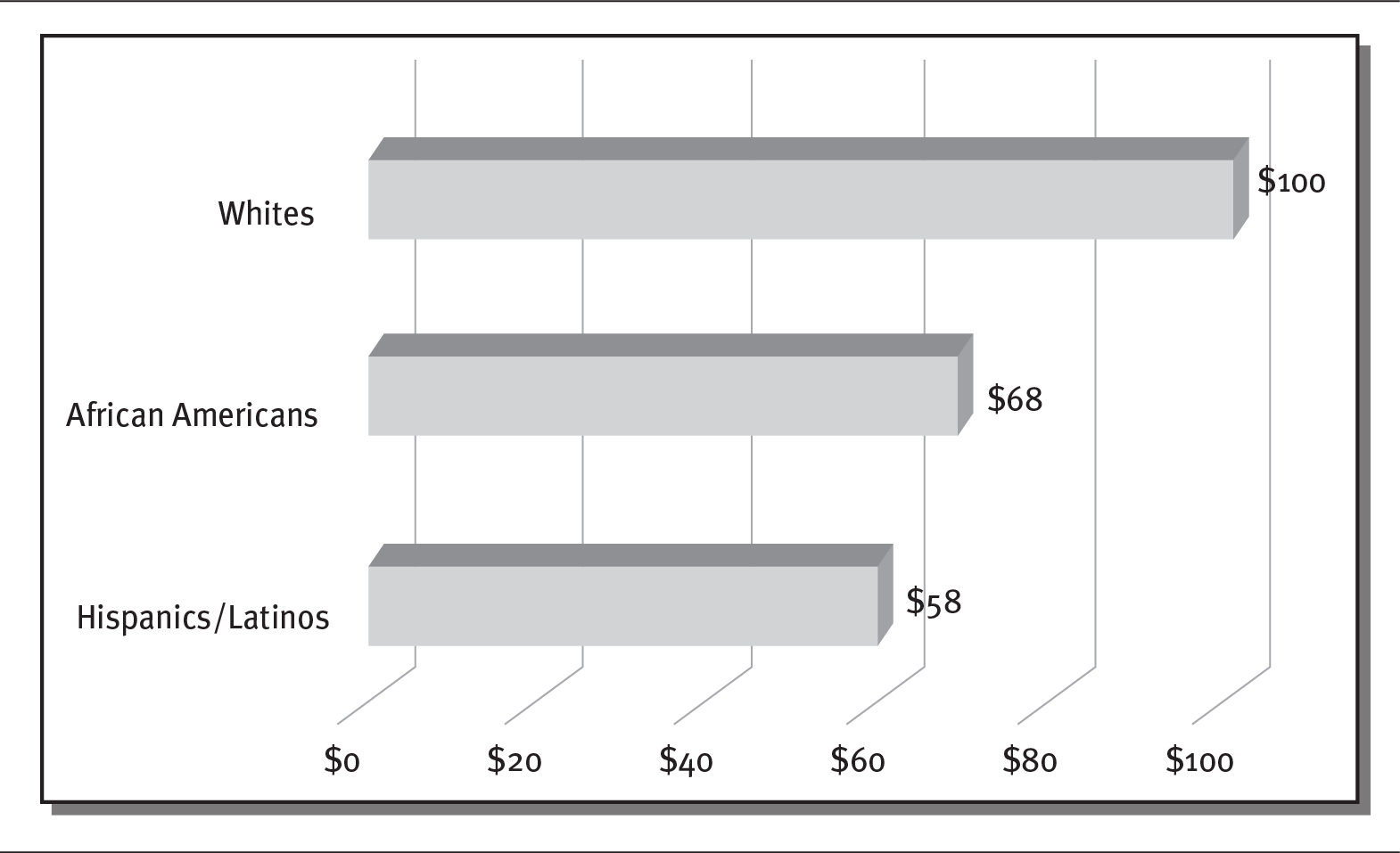

As shown in exhibit 1.7, African Americans earn 32 percent less than whites, and Hispanics/Latinos earn 42 percent less. In addition, about 20 percent of Hispanics/Latinos in 2017 did not have health insurance, and 26 percent used emergency rooms as their primary source of care (Artiga and Orgera 2019).

EXHIBIT 1.7 Earnings by Racial/Ethnic Group

Details

The x-axis shows earnings in US dollars from 0 to 100 in increments of 20. The y-axis shows the racial or ethnic groups. The details are as follows:

- Whites: 100 dollars.

- African Americans: 68 dollars.

- Hispanics or Latinos: 58 dollars.

Source: Data from Martinovich (2017).

Even though most African American and Hispanic/Latino families have at least one full-time worker, they are twice as likely as whites to be living under the federal poverty level. For this reason, many more African American and Hispanic/Latino families qualify for and receive health coverage from Medicaid. In fact, among these groups, Medicaid covers more than half of all children. In 2016, more than 55 percent of Black children and 56 percent of Hispanic/Latino children received Medicaid versus 32 percent of white children (Child Trends 2019).

Although having Medicaid coverage has been shown to improve children’s health, many states have implemented rules to reduce coverage for this population. For instance, from 2018 to 2019, enrollment of children in Medicaid declined by 840,000 nationwide. Many prominent national organizations, including the American Hospital Association, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Academy of Pediatrics, have warned that the loss of Medicaid coverage will have negative effects on the health of these children and hurt physicians’ ability to serve low-income populations (Kaiser Family Foundation 2013; Meyer 2019).

In addition, people with Medicaid coverage have a harder time finding a doctor who will accept them as a patient. Across the United States, about 30 percent of all physicians and 65 percent of psychiatrists refuse to accept new Medicaid patients (King 2019).

People of color are more likely to have co-occurring behavioral health illnesses and chronic medical conditions (see chapter 6 for a more in-depth discussion of mental health). The combination of these conditions increases the severity of disease and accentuates the effects of reduced access to care and lower income. The percentage of low-income individuals who have both a chronic disease and serious psychological stress is more than four times the rate of higher-income individuals (29 percent versus 7 percent), and this population spends over three times more on inpatient and emergency care each year. In addition, low-income individuals with chronic conditions are about 2.5 times more likely not to obtain medical care than those with higher incomes (22 percent versus 9 percent) (Cunningham 2018).

HEALTHCARE COST VARIATIONS

Research has shown significant differences in healthcare spending by geographic location. The reasons for these spending differences depend on whether the healthcare users are Medicare patients or private or commercial payers. For Medicare patients, about 73 percent of higher costs were tied to greater use of postacute services, such as skilled nursing and home health care, while about 70 percent of higher private/commercial costs were attributable to higher prices. In some US cities, Medicare costs are higher because of the greater intensity and volume of services used (see sidebar). Higher costs for commercial payers appear to be driven primarily by higher prices charged in different locations. High-cost areas are less likely to provide preventive services, such as vaccinations, but they also have much longer physician office waits and more emergency room visits. High-cost areas also use postacute services to a greater extent (Fisher and Skinner 2013; Institute of Medicine 2013).

COST VARIANCE BY GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION

COST VARIANCE BY GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION

Studies show that higher healthcare costs are largely attributable to the number of healthcare providers and other “supply-side” factors that permit providers to establish higher prices and operate less efficient clinical practices (Callison, Kaestner, and Ward 2018). For example, McAllen, Texas, had one of the most expensive healthcare markets for Medicare in the United States. In 2006, Medicare paid almost twice as much per beneficiary there (about $15,000) as the US average, primarily because of spending on postacute services. McAllen’s per capita income was only $12,000—meaning that Medicare paid more than the average resident of McAllen earned.

Patients in McAllen received more treatment and services than patients in other areas of the country. Medicare patients had about 50 percent more specialist visits, and two-thirds saw ten or more specialists. McAllen’s physicians ordered 20 to 60 percent more diagnostic tests (Gawande 2009), such as ultrasounds, bone density testing, echocardiography, nerve conduction, and urine flow studies. As a result, this population had a higher likelihood of undergoing more surgeries and invasive procedures, such as gallbladder operations, knee replacements, breast biopsies, pacemaker and defibrillator implantations, and cardiac bypass operations.

The same thing occurs with private and commercial payers, who pay very different amounts for similar services, depending on geographic location. For instance, in 2016, the cost of a knee replacement in South Carolina was $47,000 but only $24,000 in New Jersey. Similarly, a fetal ultrasound cost $522 in Cleveland but only $183 in Canton, Ohio (Herman 2016). Difference in what is paid is due mainly to differences in prices set by providers rather than to differences in the use of healthcare services.

Charges for services provided to patients can vary dramatically by location. For example, as seen in exhibit 1.8, in 2016, the median price for a cesarean (C-section) delivery was $7,742 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, but $20,721 in San Francisco, California (Kennedy et al. 2019). The prevalence of preventive care also varies by geography in the United States. For example, in 2015, children’s immunization rate for hepatitis was 88 percent in North Dakota but only 49 percent in Vermont (Hill et al. 2016).

EXHIBIT 1.8 Price Differences for C-Section in the United States

Details

The details of cost in US dollars for the following states are as follows:

- San Francisco: 20721 dollars.

- Philadelphia: 13337 dollars.

- Jacksonville: 11235 dollars.

- Salt Lake City: 10149 dollars.

- San Antonio: 7949 dollars.

- Oklahoma City: 7742 dollars.

LIFE EXPECTANCY, LIFESTYLE, AND CHRONIC DISEASE

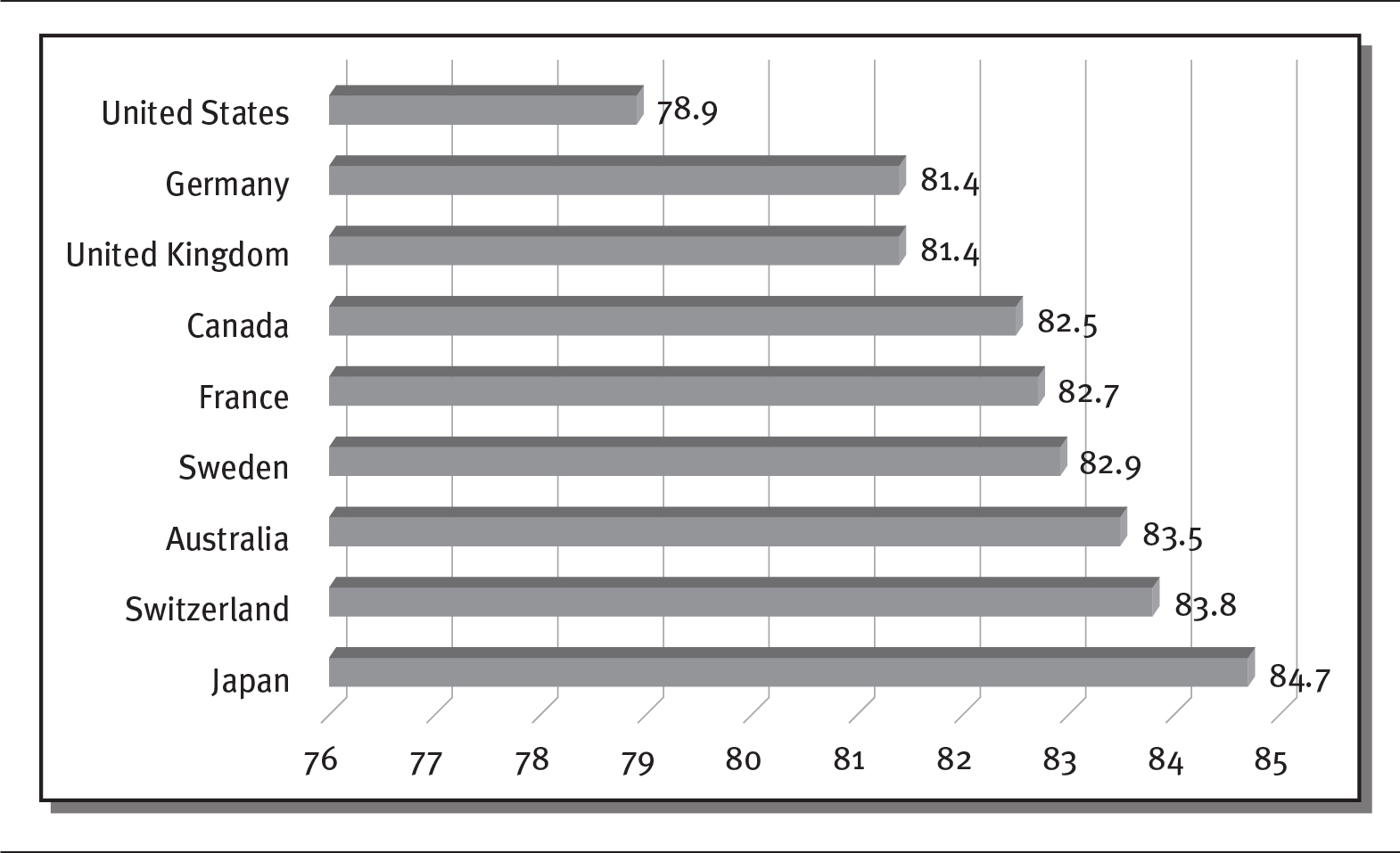

Between 2010 and 2019, life expectancy in the United States declined for the first time since the early twentieth century, and in 2020, it stood at 78.9 years. As illustrated in exhibit 1.9, US life expectancy has dropped below the average for countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In 1960, the United States had the highest life expectancy in the world, but by 1998, it had fallen below the OECD average. While US life expectancy rose between 1998 and 2012, it plateaued in 2012 and then declined from 2010 to 2019.

EXHIBIT 1.9 Life Expectancy at Birth by Nation, 2020

Details

The x-axis shows average number of years from 76 to 85 in increment of 1 year. The y-axis shows the various nations. The details of the life expectancy are as follows:

- United States: 78.9

- Germany: 81.4

- United Kingdom: 81.4

- Canada: 82.5

- France: 82.7

- Sweden: 82.9

- Australia: 83.5

- Switzerland: 83.8

- Japan: 84.7.

Source: Data from Macrotrends (2020).

Americans’ lower life expectancy compared with OECD countries is attributable to overall poorer health and to factors such as worse birth outcomes and higher numbers of injuries at birth, as well as increasing rates of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, drug overdose, and homicide.

Americans are more likely than people in other nations to eat too many calories, abuse drugs, and misuse firearms. On average, Americans eat more than 3,600 calories each day, far beyond the 2,000 calories recommended (Renee 2018), and do not exercise as much as recommended. As a result, by 2020, the CDC reported that 42 percent of adults in the United States were obese, and 9 percent were severely obese (Hill et al. 2020). In 2017 alone, more than 70,000 Americans died from drug overdoses (National Institute on Drug Abuse 2019). And, almost 40,000 people die each year from gun-related injuries, including almost 24,000 suicides (Gramlich 2019). Americans also drive cars more often, thereby getting less exercise from walking; they have weaker social networks that help support and maintain healthy lifestyles; and many people lack health insurance (Woolf and Aron 2018).

Americans’ unhealthy lifestyles encourage the onset and severity of disease. In 2014, Dr. David Katz, director of Yale University’s Prevention Research Center, stated that “We have known now for decades that the ‘actual’ causes of premature death in the United States are not the diseases [written] on death certificates, but factors that cause those diseases” (Park 2014).

Researchers believe that about 40 percent of the major causes of death in the United States, such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, lower respiratory illness, and unintentional injuries, could be prevented by modifying bad habits. Reducing or eliminating smoking and drinking, increasing exercise, and eating a healthier diet, coupled with a decrease in obesity, could dramatically improve Americans’ life expectancy, experts say (CDC 2020b).

The comparative decline in life expectancy in the United States is also directly related to the lower amount of money spent on social services. There appears to be a trade-off between money spent on healthcare and social services, such as housing assistance, food assistance, and child support services. The United States spends only about 56 cents on social services for each dollar it spends on healthcare services. On the other hand, OECD countries, which spend far less on healthcare per citizen, spend $1.70 on average on social services for each healthcare dollar. Based on this evidence, some believe that the United States could lower its healthcare costs by investing more in social services to prevent disease and related expenditures (Butler 2016).

NEW DISEASES

In addition to meeting the current challenges of healthcare in the United States and around the world, countries and healthcare systems must also anticipate new diseases whose source and timing are uncertain. For example, antibiotic-resistant infections have already become a serious concern. Because bacteria are constantly mutating, existing antibiotics may eventually become ineffective; this has already occurred with infectious diseases such as gonorrhea and tuberculosis. In 2018, more than 2 million Americans became infected with antibiotic-resistant germs, and 23,000 die from these infections each year (Scutti 2018).

The twenty-first century already has seen global outbreaks of new diseases such as the bird flu, Zika, Ebola, and COVID-19. Many of these diseases originate in the exchange of bacteria or viruses from animals to people. For example, the bird flu (avian influenza, also known as H5N1) first spread from birds to humans in 2013 and has continued to resurface since them. The disease has been devastating to bird populations; in humans, it has a 40 percent mortality rate and has killed more than 600 people (Liu 2017; McKenna 2016). Zika, originally identified in Uganda, is a type of virus that mutates frequently and spreads from a species of mosquito. The virus, which causes severe birth defects, became an epidemic in Brazil in 2015 and 2016 and quickly extended to most of the Americas (Musso 2015). Ebola, a virus that is endemic in many African countries, exploded between 2014 and 2016, with fatalities ranging from 25 to 90 percent of those infected (WHO 2020). COVID-19 exploded across the globe in 2019 and 2020, which caused the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a public health emergency of international concern. The virus is suspected to have originated in bat populations and can cause severe respiratory problems, especially among the elderly and infirm (CDC 2020a).

The United Nations has warned that other new diseases are likely to emerge and that a pandemic sweeping across the globe could kill up to 80 million people. Aside from waiting for a global disease that will kill many, the WHO is constantly battling epidemics across the world. Between 2011 and 2018, the WHO has worked to contain nearly 1,500 epidemics worldwide (Garrett 2019).

The WHO has identified a list of unknown diseases that require accelerated research (exhibit 1.10). The last disease on that list, labeled “Disease X,” represents the next big epidemic, which will come from a completely unexpected source, a pathogen, or vector that is currently unknown. To prepare for Disease X, countries need to take the following steps (Lee 2018):

EXHIBIT 1.10 Diseases Identified by the World Health Organization Requiring Accelerated Research

Details

The details of the list are as follows:

- Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever

- Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus disease

- Lassa fever

- Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

- Nipah and henipaviral diseases

- Rift Valley fever

- Zika

- Disease X.

Source: WHO (2019).

- Improve surveillance systems to detect new diseases.

- Increase access to healthcare to ensure that diseases are identified and controlled quickly.

- Set aside funds to fight the next big disease.

- Establish research and development systems to rapidly develop new vaccines and medications to combat emerging diseases.

- Ensure that supply chain and delivery systems work for the distribution of vaccines and medications.

SUMMARY

The complicated system of healthcare in the United States has its roots in the early days of the nation, when healthcare was fragmented among a variety of unlicensed practitioners who may or may not have received formal medical training. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, healthcare professions, licensure, and hospitals gained prominence as scientific discoveries improved health outcomes and as organizations such as the American Medical Association (AMA) helped standardize medical education based on the recommendations of the Flexner Report. The creation of railroads, canals, telephones, and automobiles facilitated greater access to care by lowering the cost and time to obtain healthcare services.

These developments allowed more people to access healthcare and bolstered the central role of hospitals. By the early 1900s, most physicians were receiving their education in hospitals. Advances in medical technology for diagnosis and treatment required expensive equipment that was concentrated in hospitals. With the growth of hospitals, the roles of healthcare professionals became more clearly defined. Over time, funding for hospitals shifted from charitable organizations to patients, insurance companies, and employers.

The pharmaceutical industry also emerged during this period. By the middle of the twentieth century, laws had been passed to require prescriptions from physicians for designated drugs. Patent drugs with secret ingredients were eliminated, and the safety of drugs was regulated.

As the US healthcare system developed, the struggle to balance access, cost, and quality became apparent. These three dimensions, known as the “Iron Triangle” of Healthcare, are interrelated—that is, a change in one dimension necessarily affects the others. The rising cost of healthcare, especially since the middle of the twentieth century, has put pressure on access and quality of care.

The struggle to balance access, cost, and quality becomes more difficult as Americans grow older and sicker. The United States, like most industrialized countries, has an aging population with ever more chronic illnesses. Obesity, which is linked to diabetes and other chronic diseases, affects almost one-third of US adults. As a result, the elderly and those with chronic diseases spend much more on healthcare services.

People of color have historically had more difficulty accessing healthcare services and health insurance. As a result, they have traditionally received lower-quality care and experienced worse health outcomes. African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos are more frequently covered by government healthcare programs, with Medicaid covering more than half of African American and Hispanic/Latino children. These groups also tend to have a higher incidence of behavioral health illness and chronic disease.

Research has shown that healthcare spending varies by geographic location. Higher costs for Medicare patients are tied to greater use of postacute services, while higher costs for private and commercial payers are attributable to higher prices.

Life expectancy in the United States reached a plateau in 2012 and has declined since then. Americans’ life expectancy, at 78.6 years in 2016, is now well below that of other industrialized nations. The decline is the result of worse birth outcomes and higher injuries at birth; conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, as well as drug overdose and homicide; and a weaker social support system. Countries with higher social support services appear to spend less money on healthcare services. In addition, unhealthy behaviors cause the onset and severity of chronic diseases. Almost 40 percent of disease, it is estimated, could be prevented by modifying bad habits.

In addition to these challenges, the United States—with the rest of the world—faces the threat of new diseases that could have serious effects on the healthcare system. Physicians are already seeing antibiotic-resistant infections. Other global outbreaks are expected, with new diseases originating in almost any location. The World Health Organization and other public health agencies are preparing for new, unknown diseases in the future.

QUESTIONS

- How did improvements in transportation facilitate the expansion of healthcare in the United States?

- Before the 1700s, how was the role of the physician distinguished from that of a surgeon or an apothecary?

- How did the American Medical Association, along with local medical societies, help organize and standardize medical training?

- What was the Flexner Report, and what changes resulted from it?

- What was a “patent” medicine?

- What are the three dimensions of the “Iron Triangle” of Healthcare? How are they related?

- What are the three components of the IHI Triple Aim? How does the Triple Aim differ from the Iron Triangle of Healthcare?

- What are two reasons why minorities have greater difficulty obtaining healthcare services and health insurance in the United States?

- Why are costs for Medicare patients and for private and commercial payers higher in some parts of the country than in others?

- What are some of the reasons for the decline in US life expectancy?

- What can be done to prepare for new diseases in the future?

ASSIGNMENTS

- Why does the United States spend so much more on healthcare? Read the following article: “Why Does the U.S. Spend So Much More on Healthcare? It’s the Prices,” Modern Healthcare, April 7, 2018, available at www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180407/NEWS/180409939. Write a one-page essay that answers the following questions:

- What are some of the reasons for the healthcare spending gap between the United States and other countries?

- Why are healthcare administrative costs so much higher in the United States than in other countries?

- What actions does the author suggest to control US healthcare costs? If these actions are taken, what impact to you think they would have on healthcare quality and access?

- How are companies such as Amazon and Walmart working to change the US healthcare system? Read the following article: “Amazon Could Do a Lot to Fix the U.S. Healthcare System—but Walmart Could Do More,” CNBC, April 4, 2018, available at www.cnbc.com/2018/04/04/walmart-has-more-power-to-fix-us-health-care-system-than-walmart.html. Write a one-page essay explaining why Walmart might be more effective in changing the US healthcare system than Amazon.

CASES

NURSING AND PHYSICIAN POWER

Jim is a registered nurse who recently completed his degree. He took his first nursing job at University Specialty Hospital, where he was excited to contribute to improving the health of his patients.

On his first day after orientation, Jim was assigned to a medical floor with eight patients in his care. One of his patients, Flora, was quite ill, and Jim thought that he should contact her attending physician to change her medication. One of the other nurses cautioned him about calling her doctor, Dr. Tall, as he had a reputation of being rather short with nurses and quite arrogant. Jim felt that it was important for the medication administration to take place soon and, disregarding his colleague’s advice, called Dr. Tall. Jim introduced himself and started telling the doctor about his suggested change in the medication. Jim was unable to finish, as Dr. Tall cut him off in the middle of a sentence and started yelling: “Understand—YOU DO NOT PRACTICE MEDICINE! Never question my orders!” The doctor hung up.

Jim was embarrassed and disappointed. He questioned why the doctor had such power over him and why he would not listen.

Discussion Questions

- Based on what you learned in chapter 1, what historical developments shaped the dominant role that doctors play in healthcare?

- What could Jim do the next time he encounters a problem with a patient?

- What could Jim do to change the dynamic with Dr. Tall?

DIVERSITY IN HEALTHCARE

By 2020, more than half of US children will belong to a minority racial or ethnic group, and by 2060, this share will increase to 64 percent. At the same time, health professionals are transitioning to a more patient-centered model of care, as patients demand more personalized services and want to be comfortable with their healthcare providers and care teams. Although studies have shown that greater representation of minorities in healthcare professions improves access to care for those minority communities (NCSL 2014), only about 5 percent of doctors, dentists, and nurses now come from minority racial and ethnic groups.

Discussion Questions

- What are some reasons why minorities lack equal representation in healthcare professions?

- How might having more minorities in healthcare professions affect access to healthcare for those populations?

- What actions would you take to improve opportunities for minorities to enter healthcare professions?

REFERENCES

American Hospital Association (AHA). 2020. “Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2020.” Accessed March 3. www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals.

Amondson, C. 2013. “10 Dangerous Drugs Once Marketed as Medicine.” Published April 8. www.bestmedicaldegrees.com/10-dangerous-drugs-once-marketed-as-medicine.

Artiga, S., and K. Orgera. 2019. “Key Facts on Health and Healthcare by Race and Ethnicity.” Kaiser Family Foundation. Published November 12. www.kff.org/disparities-policy/report/key-facts-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/.

Bazar, E. 2018. “Without Obamacare Penalty, Think It’ll Be Nice to Drop Your Plan? Better Think Twice.” Kaiser Health News. Published December 5. https://khn.org/news/without-obamacare-penalty-think-itll-be-nice-to-drop-your-plan-better-think-twice/.

Berwick, D. W., T. W. Nolan, and J. Whittington. 2008. “The Triple Aim: Care, Health and Cost.” Health Affairs 27 (3): 759–69.

Butler, S. M. 2016. “Social Spending, Not Medical Spending, Is Key to Health.” Brookings Institution. Published July 13. www.brookings.edu/opinions/social-spending-not-medical-spending-is-key-to-health/.

Callison, K., R. Kaestner, and J. Ward. 2018. “A Test of Supply-Side Explanations of Geographic Variation in Health Care Use.” Vox. Published October 13. https://voxeu.org/article/explaining-geographic-variation-health-care-use.

Cannon, C. M. 2019. “Medicare for All Support Is High . . . but Complicated.” RealClear Opinion Research. Published May 15. www.realclearpolitics.com/real_clear_opinion_research/new_poll_shows_health_care_is_voters_top_concern.html.

Carroll, A. 2012. “The ‘Iron Triangle’ of Healthcare: Access, Cost and Quality.” news@JAMA. Published October 3. https://newsatjama.jama.com/2012/10/03/jama-forum-the-iron-triangle-of-health-care-access-cost-and-quality/.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2020a. “Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Summary.” Updated March 9. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/summary.html.

———. 2020b. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Accessed April 2. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/index.html.

———. 2020c. “National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.” Accessed March 10. www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm.

Chappell, B. 2017. “Census Finds a More Diverse America, as Whites Lag Growth.” National Public Radio, June 22. www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/06/22/533926978/census-finds-a-more-diverse-america-as-whites-lag-growth.

Child Trends. 2019. “Trends in Children’s Health Care Coverage.” Accessed October 6. www.childtrends.org/indicators/health-care-coverage.

Cohn, D., and A. Caumont. 2016. “10 Demographic Trends That Are Shaping the U.S. and the World.” Pew Research Center. Published March 31. www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/03/31/10-demographic-trends-that-are-shaping-the-u-s-and-the-world/.

Cunningham, P. J. 2018. “Income Disparities in the Prevalence, Severity, and Costs of Co-occurring Chronic and Behavioral Health Conditions.” Commonwealth Fund. Published February 26. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/in-the-literature/2018/feb/income-disparities-chronic-behavioral-health.

Fisher, E., and J. Skinner. 2013. “Making Sense of Geographic Variation in Healthcare: The New IOM Report.” Health Affairs Blog. Published July 24. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20130724.033319/full/.

Galvin, G. 2018. “Population Health: The ‘North Star’ of the Triple Aim.” U.S. News & World Report. Published May 25. www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/articles/2018-05-25/a-decade-later-triple-aim-health-care-framework-offers-lessons-promise.

Garrett, L. 2019. “The World Knows an Apocalyptic Pandemic Is Coming.” Foreign Policy. Published September 20. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/09/20/the-world-knows-an-apocalyptic-pandemic-is-coming/.

Gawande, A. 2009. “The Cost Conundrum.” New Yorker. Published June 1. www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/06/01/the-cost-conundrum.

Godfrey, T. 2012. “What Is the Iron Triangle of Healthcare?” Penn Square Post. Published March 3. http://pennsquarepost.com/what-is-the-iron-triangle-of-health-care/.

Gramlich, J. 2019. “What the Data Says About Gun Deaths in the U.S.” Pew Research Center. Published August 15. www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/08/16/what-the-data-says-about-gun-deaths-in-the-u-s/.

Hayes, S. L., P. Riley, D. C. Radley, and D. McCarthy. 2017. “Reducing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to Care: Has the Affordable Care Act Made a Difference?” Commonwealth Fund. Published August 24. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2017/aug/racial-ethnic-disparities-care.

Herman, B. 2016. “The Striking Variation of Commercial Healthcare Prices.” Modern Healthcare. Published April 27. www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20160427/NEWS/160429918.

Hill, C., M. Carroll, C. Fryar, and C. Ogden. 2020. “Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017–2018.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 360. Published February. www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db360.htm.

Hill, H., L. Elam-Evans, D. Yankey, J. Singleton, and V. Dietz. 2016. “Vaccination Coverage Among Children 15–39 Months, United States, 2015.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Published October 7. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6539a4.htm.

Howe, C. 2016. “How Bellevue Went from a Desolate New York Almshouse and Mental Hospital to Top Medical Facility.” Daily Mail. Published November 22. www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3938852/How-Bellevue-went-desolate-New-York-almshouse-medical-facility.html.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). 2020. “The IHI Triple Aim.” Accessed June 1. www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx.

Institute of Medicine. 2013. Variation in Healthcare Spending: Target Decision Making, Not Geography. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

———. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Johnson, T. 2017. “Analysis: Healthcare Should Be a Right, but the U.S. Doesn’t Have a System.” ABC News. Published November 23. http://abcnews.go.com/Health/analysis-health-care-us-system/story?id=51281693.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2013. “Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity: The Potential Impact of the Affordable Care Act.” Published March 13. www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-the-potential-impact-of-the-affordable-care-act/.

Kennedy, K., W. Johnson, S. Rodriguez, and N. Brennan. 2019. “Past the Price Index: Exploring Actual Prices Paid for Specific Services by Metro Area.” Health Cost Institute. Published April 30. https://healthcostinstitute.org/in-the-news/hmi-2019-service-prices.

King, R. 2019. “Medicaid Enrollees Last in Line When Docs Accepting New Patients.” Modern Healthcare. Published January 14. www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20190124/NEWS/190129962/medicaid-enrollees-last-in-line-when-docs-accepting-new-patients.

Kissick, W. 1994. Medicine’s Dilemmas: Infinite Needs Versus Finite Resources. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lee, B. Y. 2018. “Disease X Is What May Become the Biggest Infectious Threat to Our World.” Forbes. Published March 10. www.forbes.com/sites/brucelee/2018/03/10/disease-x-is-what-may-become-the-biggest-infectious-threat-to-our-world/#12e010be2cd7.

Liu, M. 2017. “Is China Ground Zero for a Future Pandemic?” Smithsonian Magazine. Published November. www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/china-ground-zero-future-pandemic-180965213/.

Macrotrends. 2020. “US Life Expectancy 1950–2020.” Accessed June 1. www.macrotrends.net/countries/USA/united-states/life-expectancy.

Manchikanti, L., L. Helm, R. Benyamin, and J. Hirsch. 2017. “A Critical Analysis of Obamacare.” Pain Physician 20 (3): 111–38.

Martinovich, M. 2017. “Significant Racial and Ethnic Disparities Still Exist, According to Stanford Report.” Stanford News. Published June 16. https://news.stanford.edu/2017/06/16/report-finds-significant-racial-ethnic-disparities/.

McKenna, M. 2016. “The Looming Threat of Avian Flu.” New York Times. Published April 17. www.nytimes.com/2016/04/17/magazine/the-looming-threat-of-avian-flu.html.

Meyer, H. 2019. “Medicaid, CHIP Enrollment for Kids Dropped by 840,000 in 2018.” Modern Healthcare. Published April 25. www.modernhealthcare.com/government/medicaid-chip-enrollment-kids-dropped-840000-2018.

Mikulic, M. 2019. “Global Pharmaceutical Industry—Statistics & Facts.” Statista. Published August 13. www.statista.com/topics/1764/global-pharmaceutical-industry/.

Musso, D. 2015. “Zika Virus Transmission from French Polynesia to Brazil.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 21 (10): 1887.

National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). 2014. “Diversity in Healthcare Workshop.” Published August. www.ncsl.org/documents/health/workforcediversity814.pdf.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. 2019. “Overdose Death Rates.” Revised January. www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

Neuman, T., J. Cubanski, J. Huang, and A. Damico. 2015. “The Rising Cost of Living Longer: Analysis of Medicare Spending by Age for Beneficiaries in Traditional Medicare.” Kaiser Family Foundation. Published January 14. www.kff.org/medicare/report/the-rising-cost-of-living-longer-analysis-of-medicare-spending-by-age-for-beneficiaries-in-traditional-medicare/.

O’Brien, S. 2019. “Health-Care Costs for Retirees Climb to $285,000.” CNBC. Published April 2. www.cnbc.com/2019/04/02/health-care-costs-for-retirees-climb-to-285000.html.

Park, A. 2014. “Nearly Half of U.S. Deaths Can Be Prevented with Lifestyle Changes.” Time. Published May 1. http://time.com/84514/nearly-half-of-us-deaths-can-be-prevented-with-lifestyle-changes/.

Pew Research Center. 2015. “Immigration’s Impact on Past and Future U.S. Population Change.” Published September 28. www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2015/09/28/chapter-2-immigrations-impact-on-past-and-future-u-s-population-change/.

Rahalkar, H. 2012. “Historical Overview of Pharmaceutical Industry and Drug Regulatory Affairs.” Pharmaceutical Regulatory Affairs S11-002. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-7689.S11-002.

Renee, J. 2018. “The Average Calorie Intake by a Human per Day Versus the Recommendation.” San Francisco Chronicle. Published December 2. https://healthyeating.sfgate.com/average-calorie-intake-human-per-day-versus-recommendation-1867.html.

Rutledge, G., K. Lane, C. Merlo, and J. Elmi. 2018. “Coordinated Approaches to Strengthen State and Local Public Health Actions to Prevent Obesity, Diabetes, and Heart Disease and Stroke.” Public Health Research Practice and Policy 15 (E14): 1–7. www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2018/pdf/17_0493.pdf.

Sawyer, B., and G. Claxton. 2019. “How Do Health Expenditures Vary Across the Population?” Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. Published January 16. www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-expenditures-vary-across-population/#item-start.

Scutti, S. 2018. “Unusual Forms of ‘Nightmare’ Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Detected in 27 States.” CNN. Published April 3. www.cnn.com/2018/04/03/health/nightmare-bacteria-cdc-vital-signs/index.html.

———. 2017. “4 Reasons Why U.S. Healthcare Is So Expensive.” CNN. Published November 7. www.cnn.com/2017/11/07/health/health-care-spending-study/index.html.

Shahbandeh, M. 2019. “Total Number of Retail Prescriptions Filled Annually in the U.S.” Statista. Published November 12. www.statista.com/statistics/261303/total-number-of-retail-prescriptions-filled-annually-in-the-us.

Starr, P. 1982. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books.

Statista. 2020. “Top 10 Causes of Death in the U.S. in 1900 and 2018 (per 100,000).” Accessed June 1. www.statista.com/statistics/235703/major-causes-of-death-in-the-us/.

———. 2019. “U.S. National Health Expenditure as Percent of GDP from 1960 to 2019.” Accessed June 1, 2020. www.statista.com/statistics/184968/us-health-expenditure-as-percent-of-gdp-since-1960/.

Turow, J. 2010. Playing Doctor: Television, Storytelling and Medical Power. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

US Census Bureau. 2019. “Quick Facts.” Accessed June 1, 2020. www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/RHI225218#RHI225218.

———. 1993. “Population: 1790 to 1990.” Accessed March June 1, 2020. www.census.gov/population/censusdata/table-4.pdf.

Venosa, A. 2016. “History of the Pharmacy: How Prescription Drugs Began and Transformed into What We Know Today.” Medical Daily. Published March 16. www.medicaldaily.com/pharmacy-prescription-drugs-378078.

Weiner, J., C. Marks, and M. Pauly. 2017. “Effects of the ACA on Healthcare Cost Containment.” Issue Brief, University of Pennsylvania, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics. Published March 2. https://ldi.upenn.edu/brief/effects-aca-health-care-cost-containment.

Whicher, D., K. Rosengren, S. Siddiqi, and L. Simpson (eds.). 2018. The Future of Health Services Research: Advancing Health Systems Research and Practice in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/The-Future-of-Health-Services-Research_web-copy.pdf.

Woolf, S., and L. Aron. 2018. “Failing Health of the United States.” BMJ 360: k496.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2020. “Ebola Virus Disease: Fact Sheet.” Updated February 10. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs103/en/.

———. 2019. “Prioritizing Diseases for Research and Development in Emergency Contexts.” Accessed March 3, 2020. www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/en/.