3. Bittersweet

“You know, the White House is really modeled after a plantation big house.” Chef Walter Scheib startled me when he said this during our first telephone conversation on 12 October 2010. It wasn’t because of concerns over the accuracy and clarity of his statement but because he said it to someone he really didn’t know. That’s just one of the reasons why, since his tragic death, I really miss the chance to delve more deeply with him into the complicated racial history of the presidential kitchen. Just like the white paint that is periodically applied to the White House exterior to cover up the scorch marks left when the British set the building afire in late August 1814, the retelling of White House history frequently masks the stain of slavery. This is maddening stuff given how deeply the legacy of slavery permeates the building, its grounds, and the entire city. Washington, D.C., was carved out of swampland from two slaving states (Maryland and Virginia), the land was donated by planters who were enriched by tobacco slave labor, slave labor was used to construct the building, and slaveholding presidents and enslaved people lived and worked there.1

Before we focus on what happened within the White House’s walls, it helps to understand what antebellum black life was like in our nation’s capital during the nineteenth century. For most African Americans, it was miserable. Washington, D.C., was a slaving city, and the incidents and badges of slavery were omnipresent: enslaved people were sold at spots throughout the city, slave coffles moved regularly about the streets, slave pens dotted the cityscape, and enslaved people busily constructed many of the city’s buildings and much of its infrastructure and did a wide range of activities associated with forced servitude. D.C. operated under its own set of “Black Codes.” Such laws constrained the liberty of both enslaved and free African Americans. For example, the city’s 1808 Black Code enforced a 10 P.M. curfew on all African Americans that, if violated, was punishable by a fine. In the 1812 iteration of that particular code, enslaved people who violated the curfew were whipped with forty lashes. Free black people were also fined and could be jailed for up to six months if fines went unpaid. During this time, no black person could step on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol unless they had documented official business.2

Black Codes were designed to preserve a racial social order and, at first, were slowly enacted after enslaved Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619. As the number of enslaved Africans dramatically increased in the eighteenth century, Black Codes proliferated in slaving states. The Black Codes, white racism, and white resistance to black progress combined with a cruel efficiency to constantly remind African Americans of their second-class status. In fact, it’s hard to imagine any social event in nineteenth-century Washington, D.C., that didn’t have an African American somehow involved in every aspect from start to finish. This included buying supplies at the market and preparing and serving the food and drinks. As one historian noted of the time period, “Nearly every distinguished family in Washington had colored servants, butlers and cooks and entertained lavishly. White servants and cooks came later.”3 Black hands—enslaved and free—wove the fabric of social life in the nation’s capital, and black people, widely considered by whites as inherently bred for servitude, were integral to cementing a white family’s social status as an elite household. Our presidential families were no exception, and this chapter delves into how slave labor powered the White House kitchen and nourished our presidents and, in one case, a future president. We’ll peer into the lives of people we can name (Hercules, James Hemings, and Mary Dines) and many whom white society didn’t feel obligated to identify by name in documented accounts of daily life at the White House.

We begin with Hercules (nicknamed “Uncle Harkles”), the enslaved cook for President George Washington. After experimenting with a couple of white cooks—a woman named Mrs. Read was one—President Washington summoned Hercules from Mount Vernon and installed him as his presidential cook in Philadelphia. George Washington’s stepgrandson, George Washington Parke Custis, did history a great service by paying some attention to Hercules’s culinary skill, professionalism, resourcefulness, and personality at a time when enslaved people were generally ignored. Some researchers and writers, most recently and notably Craig LaBan of the Philadelphia Inquirer, use Custis’s historical sketch as a starting point and have provided additional details to paint a more complete picture of Hercules’s life.

Hercules, because of his name, may have been a big child when he was born circa 1753. Custis wrote of Hercules in his memoirs, “He was a dark brown man, little, if any, above the usual size, yet possessed of such great muscular power as to entitle him to be compared with his namesake of fabulous history.”4 Being named after the strong man in the center of Greek and Roman mythology wasn’t unusual for the times because American elites were going through a deep wave of neoclassical nostalgia for ancient Rome and Athens. They fancied themselves as the true heirs of the classical period, and they evidenced this sentiment in a number of ways: places in the United States were given Roman- and Greek-inspired names (for example, Athens, Georgia, and Rome, New York), buildings evoked classical architecture, and prestigious kitchens replicated menus and prepared food straight out of old Roman cookbooks. There’s another interesting cultural confluence as well. As slavery historian Peter H. Wood explains, “The most frequent biblical and classical names accepted among slaves will reveal that they often resemble African words…. One reason that the name Hercules—often pronounced and spelled Hekles—was applied to strong slaves may well be the fact that heke in Sierra Leone was the Mende noun meaning ‘a large wild animal.’”5 Thus, the “Uncle Harkles” nickname could have been less a bad pronunciation of the name Hercules and more about the appropriation of an African word.

Washington purchased a teenage Hercules in 1767 while the latter worked as a ferryman.6 When Hercules arrived at Mount Vernon, Washington had several home improvement projects underway: “Between 1759 and his death in 1799, [Washington] expanded upon the original farmhouse his father had built to create a two-and-a-half-story, twenty-room mansion, complete with several kitchens and dining rooms, and he designed and erected the twelve outbuildings that stand today. He also increased the plantation’s size from twenty-one hundred to eight thousand acres.”7 Washington added Hercules to his workforce that included slaves he had inherited from his father, slaves he had acquired when he married Martha Dandridge, slaves he had purchased, and slaves loaned to him from neighboring slave owners. At some point, Washington transferred Hercules from ferrying boats to cooking in the Mount Vernon kitchen under the direction of Old Doll, the plantation’s chief cook, a slave whom he had acquired when he married Martha.8

Though the timing isn’t clear, Hercules eventually took Old Doll’s place in the kitchen. Washington’s slave inventory from February 1786 listed Hercules and Nathan as the cooks in the “House Home,” and Old Doll was listed as “almost past Service,” indicating her advancing age.9 By the time that Hercules took over, the kitchen had been fully renovated and updated. As the Mount Vernon website indicates,

The new kitchen was larger and more architecturally detailed than the original, matching the Mansion in many aspects. Most notably, the siding boards on the facade facing the circle were beveled and sanded to create the appearance of stone blocks. Covered walkways called colonnades were built to connect each of the new structures to the Mansion. Workers carrying food back and forth between the kitchen and the Mansion did so along a protected passageway.

The updated kitchen included three workrooms on the first floor and a loft above, which served as the residence of the cook or housekeeper. The largest of the three workrooms included a fireplace and attached oven. The other workrooms were a scullery where food was prepared and dishes were washed, and a larder with a subterranean cooling floor to store food. According to the inventory of the kitchen completed after George Washington’s death, the kitchen contained a wide variety of cooking equipment, including pots and pans, skillets, a griddle, a toaster, a boiler, spits, chafing dishes, tin and pewter “Ice Cream Pots,” coffeepots, and strainers.10

Using what appeared to be the latest cooking equipment and technology and an abundant larder from the surrounding countryside, Hercules honed his culinary skills and unwittingly prepared for his presidential moment.

Hercules was thirty-six years old when he arrived in Philadelphia to cook in the Executive Mansion. He experienced a food scene more cosmopolitan than that of other cities. A Philadelphia historian wistfully remembered in an 1860 memoir,

There was a time, in the end of the last and beginning of the present century, when the “Carrying Trade” between the United States and the West India Islands, was a fruitful source of life to the commercial interest of Philadelphia…. Our intercourse with the West Indies was active, spirited, and rich in results; for whilst our Beef and Pork, Flour, Apples, Onions, Butter, Lard, and any other product of our fields or farms, were toothsome and desirable to the planter there, the issues of their soil, of Sugar, Coffee, Oranges, Lemons, Pine-Apples, etc., paid much better here, and laid the foundation of ease and comfort to very many of the retired dealers of that day.11

Because of this extensive exotic food trade, noted African American foodways scholar Jessica B. Harris urges readers of her book Beyond Gumbo to reimagine Philadelphia as “a Creole city.”12

Though President Washington was the ultimate boss, Samuel Fraunces—now starting his second stint as presidential steward—was the one who would decide whether or not Hercules’s culinary skills were up to snuff. Tobias Lear, President Washington’s private secretary, informed the president of this fact in a letter dated 15 May 1791:

Fraunces arrived here on Wednesday, and after signing his Articles of Agreement—going over the things in the house & signing an inventory thereof, entered upon the duties of his station. I think I have made the agreement as full, explicit & binding as any thing of the kind can be. In the Articles prohibiting the use of wine at his table—and obliging him to be particular in the discharge of his duty in the Kitchen & to perform the Cooking with Hercules—I have been peculiarly pointed.

He readily assented to them all (except that respecting Hercules, upon which he made the following observation—“I must first learn Hercules’ abilities & readiness to do things, which if good, (as good as Mrs. Read’s) will enable me to do the Cooking without any other professional assistance in the Kitchen; but this experiment cannot be made until the return of the President when there may be occasion for him to exert his talents”—) and made the strongest professions of attachment to the family, & his full determination to conduct in such a manner as to leave no room for impeachment either on the score of extravagance or integrity. All these things I hope he will perform.13

History has not recorded how Washington reacted, but future president Ronald Reagan would surely have approved of Fraunces’s effort to “trust, but verify” Hercules’s culinary skill level. Coincidentally, the exotic food trade was disrupted in 1792–93 by the successful revolution happening in Fraunces’s birthplace: Haiti.

In the Philadelphia Executive Residence’s kitchen, Hercules worked with a team of eight people: Fraunces the steward, some assistant cooks (including his own enslaved teenage son Richmond), and several waiters. He cooked in a large fireplace filled with cooking equipment. This type of cooking is also known as “hearth” or “hearthside” cooking. It involves starting and tending a fire, operating numerous gadgets and cooking equipment that are either suspended over the fire or on the floor in front of the fire, or sometimes cooking food in the ashes of the fire.14 Such hearth cooking is difficult and dangerous, but, according to Custis, Hercules excelled at it:

The chief cook would have been termed in modern parlance, a celebrated artiste. He was named Hercules, and familiarly termed Uncle Harkless…. [He] was, at the period of the first presidency, as highly accomplished a proficient in the culinary art as could be found in the United States….

The steward, and indeed the whole household, treated the chief cook with much respect, as well for his valuable services as for his general good character and pleasing manners.

It was while preparing the Thursday or Congress dinner that Uncle Harkless shone in all his splendor. During his labors upon this banquet he required some half-dozen aprons, and napkins out of number. It was surprising the order and discipline that was observed in so bustling a scene.15

No recipes known to be attributable to Hercules survive to this day, and there are few descriptions of the meals that he made for President Washington during his time in Philadelphia from 1791 to 1797—a curious fact given President Washington’s celebrity status. Fortunately, one Washington biographer found this reference to one of those meals: “Bradbury gives the menu of a dinner at which he was, where ‘there was an elegant variety of roast beef, veal, turkey, ducks, fowls, hams, &c.; puddings, jellies, oranges, apples, nuts, almonds, figs, raisins, and a variety of wines and punches.”16 If one needs further evidence of culinary prowess, note that President Washington allowed Hercules a unique opportunity to earn additional income. As Craig LaBan notes, “Most telling … was allowing Hercules the right to sell the kitchen ‘slops’—the remaining animal skins, used tea leaves, and rendered tallow that would have been compost on the plantation. In the city, these were lucrative leftovers, an income-producing perk traditionally bestowed on top chefs…. For Hercules that meant annual earnings of up to $200, if Custis is accurate, as much as the Washingtons paid hired chefs.”17 Thus, Hercules earned upwards of $5,000 (in 2015 dollars) in extra income.18 Hercules used some of the money to acquire a spectacular wardrobe, and almost every day he walked the Philadelphia streets wearing “a blue coat with a velvet collar, a pair of fancy knee-breeches, and shoes with extravagant silver buckles. Thus attired, with a cocked hat upon his head and a gold-headed cane in his hand, he strutted up and down among the beaux and belles until the stroke of the clock reminded him that he must hurry off to the kitchen and prepare the evening meal.”19 He was quite the fashionable figure for his time.

Those who watch cooking competition shows and reality shows about restaurants on television probably think of a professional kitchen as a place where arrogant, self-absorbed chefs terrorize line cooks with abusive language and impossible demands. It appears that Hercules was that kind of chef. Custis observed, “The chief cook gloried in the cleanliness and nicety of his kitchen. Under his discipline, wo [sic] to his underlings if a speck or spot could be discovered on the tables or dressers, or if the utensils did not shine like polished silver. With the luckless wights who had offended in these particulars there was no arrest of punishment, for judgment and execution went hand in hand.”20 Evidently, Hercules ran a very tight ship: “His underlings flew in all directions to execute his orders, while he, the great master-spirit, seemed to posses the power of ubiquity, and to be everywhere at the same time.”21 What made Hercules so demanding? Was it his natural temperament? Was he reacting to a stressful environment? Perhaps it was just learned behavior from President Washington, who had a very bad temper, or a combination of all of the above. Whatever the reason, Hercules possessed a personality well-suited to being a demanding chef.

Though the Washingtons were pleased with Hercules’s cooking, having an enslaved chef in Pennsylvania created political and logistical headaches as well as a potential public relations nightmare for them. Annoyingly for President Washington, prior to him taking residence in Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania state legislature had enacted the Gradual Abolition Act of 1780. This law freed any enslaved person who stayed on Pennsylvania soil for longer than six continuous months. To skirt the law, President Washington decided, after considerable research and consultation, that the best course of action would be to send all of his slaves back to Mount Vernon every time the six-month deadline was about to toll. They would stay at the plantation for a few weeks and then return to Philadelphia to restart the “freedom clock.” President Washington surmised that his slaves, especially Hercules, were well aware of the law, and at one point late in his second presidential term, he accused Hercules of plotting to escape. According to Tobias Lear, Hercules was visibly upset that President Washington would even suspect him of such betrayal.22

It’s puzzling that President Washington would be concerned about Hercules’s possible flight, since he had previously granted him some limited freedoms. In addition to Hercules’s off-the-clock excursions, the president’s expense reports also show that Hercules and other slaves were allowed to go to the circus and the theater by themselves.23 Hercules certainly could have attempted to get away at any point during these activities but chose not to. Perhaps he refrained because he was aware that the president had signed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which would have forced his return to President Washington if he escaped and were recaptured anywhere on American soil. Hercules knew he would have only one chance to abscond, if he decided to do so, and he had to make it count.

As President Washington’s second term came to a close, he prepared for permanent retirement at Mount Vernon. Hercules was growing more desirous for freedom and must have known that the window to escape was closing. He may have been buoyed by the successful flight of Martha Washington’s longtime enslaved maid Oney Judge in April 1796 as well as of a couple of other of Washington’s slaves. However, the fact that some slaves had successfully made their getaway meant that Hercules was being more closely watched. In fact, President Washington sought to minimize the risk of Hercules’s escape by moving him back to Mount Vernon ahead of schedule. As Craig LaBan wrote,

Oney Judge proved Philadelphia was a risk. But back at Mount Vernon, surely, Hercules would be secure. The once-trusted chef, also noted for the fine silk clothes of his evening promenades in Philadelphia, suddenly found himself that November in the coarse linens and woolens of a field slave. Hercules was relegated to hard labor alongside others, digging clay for 100,000 bricks, spreading dung, grubbing bushes, and smashing stones into sand to coat the houses on the property, according to farm reports and a November memo from Washington to his farm manager. “That will Keep them,” he wrote, “out of idleness and mischief.” When Hercules’ son Richmond was then caught stealing money from an employee’s saddlebags, Washington made his suspicions of a planned father-son escape clear in a letter: “This will make a watch, without its being suspected by, or intimated to them.”24

Richmond’s attempted theft confirmed President Washington’s earlier suspicions of Hercules and put his former chef in a more precarious position. Washington thus took extra steps to make it more difficult for Hercules to escape. Yet, that doesn’t mean we should count Hercules out.

In early 1797, Hercules dashed for freedom. The conventional wisdom held that he had escaped in Philadelphia before President Washington left the city and returned to private life at Mount Vernon. However, some recent historical detective work has caused researchers to reassess that timeline. Following up on recent discoveries by some Washington historians, LaBan wrote, “Before dawn on Feb. 22, 1797, he launched his quest for freedom. The recent discovery by Mount Vernon historian Mary V. Thompson of this key detail in the weekly farm report from Feb. 25, 1797—‘Herculus [sic] absconded 4 [days ago]’—has finally solved two long-held mysteries: the place and timing of Hercules’ flight.”25 In reality, Hercules made the gutsy move to leave on President Washington’s birthday! Hercules must have shrewdly calculated that all of the activity surrounding the birthday festivities at Mount Vernon would distract others from noticing his absence.

The president’s reaction to Hercules’s escape played out for nearly a year’s time, and Washington demonstrated a dogged refusal to accept that this master-slave relationship had ended. In January 1798, almost a year after Hercules took flight, the former president was still making inquiries and marshaling his resources to recapture Hercules. This is not so surprising, given the similar efforts Washington had made to recapture Oney Judge, Martha Washington’s personal slave, who had successfully escaped to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in May 1796. Several months later, the president had orchestrated an ultimately unsuccessful scheme to kidnap Judge and forcibly return her to Mount Vernon, Virginia. His key middleman was none other than Oliver Wolcott, his secretary of the treasury. In a 1 September 1796 letter to Wolcott, President Washington wrote, “I am sorry to give you, or any one else trouble on such a trifling occasion, but the ingratitude of the girl, who was brought up and treated more like a child than a Servant (and Mrs. Washington’s desire to recover her) ought not to escape with impunity if it can be avoided.”26

On 13 November 1797, nine months after Hercules had absconded, a still seething Washington fired off another letter to George Lewis. He wrote, “The running off of my Cook, has been a most inconvenient thing to this family; and what renders it more disagreeable, is, that I had resolved never to become the Master of another Slave by purchase; but this resolution I fear I must break. I have endeavored to hire, a black or white, but am not yet supplied.”27 Washington’s temper is best described as “volcanic”—his eruptions were infrequent and intense. As presidential historian Thomas Fleming wrote, “Not many people made George Washington lose his temper. His self-control was legendary. But when he lost it, the explosion was something witnesses never forget.”28 This letter makes Hercules sounds indispensable to the Mount Vernon kitchen, but clearly the Washingtons had gone without his cooking before. Recall that Washington had Hercules working in the fields in the weeks prior to his flight. This suggests that the hard labor was temporary punishment to “teach Hercules a lesson” for thinking about escape while in Philadelphia. In addition, President Washington had numerous slaves that he could have forced to cook. Apparently, spite motivated the man whose presidency was a fading memory; running a slave-operated plantation was apparently now his primary occupation.

The former president sounded rather sad and depressed as he closed his 10 January 1798 letter to a Mr. Kitt: “We have never heard of Hercules our Cook since he left this [place]; but little doubt remains in my mind of his having gone to Philadelphia, and may yet be found there, if proper measures were employed to discover (unsuspectedly, so as not to alarm him) where his haunts are. If you could accomplish this for me, it would render me an acceptable service as I neither have, nor can get a good Cook to hire.”29 Martha Washington echoed this sentiment when she wrote to a friend on 20 August 1797. Brace yourself, for it reads like something right out of an episode of The Real Housewives of Old Virginia. Mrs. Washington complained, “[I] am obliged to be my one [sic] Housekeeper which takes up the greatest part of my time,—our cook Hercules went away so that I am as much at a loss for a cook as for a house keeper—altogether I am sadly plaiged [sic].”30

Once the reality of Hercules’s successful escape sunk in, one must wonder: Where did he go? Given his awareness of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and President Washington’s efforts to kidnap Oney Judge, Hercules knew he had to get as far away as possible. If I were to indulge my imagination, I might wonder whether Hercules contemplated a foreign destination in the Americas—perhaps Canada, the Caribbean, Mexico, or Central or South America. They all would have been logical choices, and with the money he had made from selling leftovers, he certainly could have financed a lengthy sojourn.

Remarkably, a few clues might indicate that Hercules may have traveled even farther than expected by crossing the Atlantic. The trail leads to the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, Spain, where a painting titled A Cook for George Washington is currently on display. The portrait is attributed to Gilbert Stuart, who also painted an iconic portrait of George Washington, but this attribution is disputed by some art historians. In assessing the clothing that Hercules wears in the portrait, Ellen Miles, the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s curator of painting and sculpture, said in a 2010 newspaper article interview that “the cut and fashion of the subject’s white coat says late 18th century.”31 In the same article, Christine Crawford-Oppenheimer, a librarian at the Culinary Institute of America, added, “But his chef’s hat is a tall toque that didn’t become popular until the early 19th century.”32 Intriguing as they may be, these clothing cues get us no closer to the actual truth. The details of Hercules’s escape itinerary remains a mystery.

One thing we know for certain is that Hercules never came back to Mount Vernon. While Hercules was away, Louis-Philippe, a French nobleman and future king of France, visited Mount Vernon a few months after the former chef’s flight. Upon meeting Hercules’s daughter Delia, he wrote in his travel diary, “The general’s cook ran away, being now in Philadelphia, and left a little daughter of six at Mount Vernon. Beaudoin [Louis-Philippe’s valet] ventured that the little girl must be deeply upset that she would never see her father again; she answered, Oh! sir, I am very glad, because he is free now.”33 Hercules’s heart must have ached from being separated from the four children he left behind—especially given that we know that his wife had died ten years earlier—but the risk of recapture was greater for an entire family than it was for one person.

Perhaps Hercules didn’t go that far after all. In 1801, New York City’s mayor, Colonel Richard Varick, who happened to be President Washington’s former recording secretary, is on record as having spotted Hercules walking around town.34 Perhaps Hercules, who had never worked for President Washington during his time in New York City, thought living there was much safer than hanging out in Philadelphia, where he would more likely be recognized. Varick immediately wrote to Martha Washington to apprise her of his discovery. The Fugitive Slave Act was still the law of the land, and Mrs. Washington could easily have forced Hercules’s return. But she declined because, by this point, she had already freed her slaves. Hercules had likely gotten news of President Washington’s death and, like the other Mount Vernon slaves, knew that Washington had desired to free them once he died.35

Varick’s report is the last eyewitness account that exists of Hercules. Yet his memory lived on in those who ate his food. In 1850, Margaret Conkling wrote in her memoirs of the Washington, D.C., dinners that she attended: “Hercules, the colored cook, was one of the most finished and renowned dandies of the age in which he flourished, as well as a highly accomplished adept in the mysteries of the important art he so long and so diligently practiced.”36 I like to imagine that Hercules vanished while at the top of his game to acquire something he desired more than fame—his freedom.

While Hercules made his mark preparing the very best in Virginia cuisine, African American cooks in elite circles became adept at making other cuisines besides southern food, and most often it was French food, the “official cuisine” of high society in America. Having a cook who could successfully execute French food was extremely important to maintaining social status as an excellent hostess. Jessie Benton Frémont was one of D.C.’s best-known socialites in the nineteenth century, and in her memoirs she gives us some valuable insight on how enslaved cooks were trained:

There have always been admirable French cooks in Washington. The foreign ministers all brought them; when they returned—if not sooner—the cooks deserted and set up in business for themselves. These not only went out to prepare fine dinners, but took as pupils young slaves sent by families to be instructed. In that way a working knowledge of good cookery of the best French school became diffused among numbers of the colored people—and for cookery they have natural aptitude. [Well-known African American caterer James] Wormley, whose hotel in Washington was famous and who has lately died leaving over a million of property, owed his success to such training, as well as to his business capacity which turned it to profit.37

One can see the French influence in several soul food dishes like spoon bread, which is technically a cornbread soufflé. Most likely we owe such dishes to the French chefs who taught recipes and techniques to enslaved cooks.

With a few exceptions (namely the presidents named “Adams”), our early presidents were wealthy men who embraced the social customs of the elite households of their day. Some followed trends and others were trendsetters, and none exemplified the latter more than Thomas Jefferson and James Hemings, Jefferson’s enslaved chef who was trained in classical French cooking. Though his experience predated Jefferson’s presidency, the culinary adventures and legacy of James Hemings reverberated for decades in terms of how White House food was prepared and perceived.

Hemings was the second-oldest brother of Sally Hemings, who is more well known today because of her now documented sexual relationship with Thomas Jefferson. Hemings was born in 1765, the son of an enslaved African woman named Elizabeth “Betty” Hemings and her enslaver, a white man named John Wayles. Wayles’s daughter was Martha Wayles Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson’s wife. That means that James Hemings was technically Martha Jefferson’s half brother and Thomas Jefferson’s brother-in-law. Hemings worked a number of jobs under Jefferson. From 1779 until 1783, while Jefferson was governor of Virginia, Hemings was a house servant and messenger and sometimes a carriage driver. Hemings’s life may have been as mundane as the lives of the other Monticello slaves, but then his life took an unexpected turn.38

In 1784, the U.S. Congress appointed Jefferson to help Benjamin Franklin and John Adams negotiate treaties with European nations; Minister Jefferson thus had to go and live in France, and he took a nineteen-year-old Hemings with him. When they arrived in France, Jefferson quickly began Hemings’s intensive, three-year study of European cuisine from 1784 to 1787. Hemings first apprenticed under a restaurant keeper named Combeaux and then learned pastry making in late 1786. Though Jefferson would poke fun at him, Hemings hired a French language tutor and was conversational in that language by 1787. Hemings then apprenticed under the cook for Prince de Condé [Louis V Joseph de Bourbon] in 1787, at great expense to Jefferson, on a country estate called Chantilly. He ultimately became chef de cuisine at Jefferson’s Paris residence—the Hôtel de Langeac. While in this position, Jefferson paid Hemings a wage of twenty-four livres a week, which was comparable to or even higher than what free white servants who were his contemporaries made.39

Some historians theorize that Jefferson may have essentially been “paying Hemings off” because he faced a similar challenge to having slaves in Paris as President Washington had with keeping slaves in Philadelphia. Much like Pennsylvania, France provided the legal means for James and his younger sister Sally, who later joined him in France, to be emancipated. Unlike the situation that Hercules had to face in Pennsylvania, though, the Hemings siblings didn’t have to wait. They were technically free as soon as they stepped on French soil under something called the “Freedom Principle.” All that was needed was for a third party to sue for their freedom on their behalf. But this never happened, and it could possibly have been due to an arrangement that Jefferson made with both Hemingses, perhaps promising to keep their family intact back at Monticello. In the meantime, Chef Hemings kept preparing the superlative food that helped build Jefferson’s reputation as an excellent host in Paris.40

Because of the combination of a new federal government being implemented at home and the rising social tumult in Paris, Jefferson, the Hemingses, and the rest of his staff left France in September 1789, a few months after the French Revolution began. Upon arriving in the United States, Jefferson found out that Washington had appointed him as the new government’s first secretary of state.41 Chef Hemings and now Secretary Jefferson took up residence in New York and then moved to Philadelphia when that city was designated as the nation’s capital.42 During President Washington’s first term, White House steward Samuel Fraunces and Chef Hercules were in Philadelphia as well, and it is entirely possible that they were aware of each other given the friendship of their influential bosses. During his time in Philadelphia, Chef Hemings continued to see his share of historic moments.

One such moment was the “deal” that led to the District of Columbia. According to Chef Ashbell McElveen, founder of the James Hemings Foundation, Hemings

was in the kitchen for the most historic dinner in early American history. On June 20, 1790, the meal—a delicious balm in his signature half-Virginian-half-French style—helped reconcile the bitter enemies Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. Over lavish courses that included capon stuffed with Virginia ham, chestnut purée, artichoke bottoms and truffles, served with a Calvados sauce, and boeuf à la mode made with French-style boeuf bouillon instead of gravy, they forged an agreement to settle the young republic’s biggest problem: how to finance the Revolutionary War debt. They also decided that the national capital would be situated along the Potomac.43

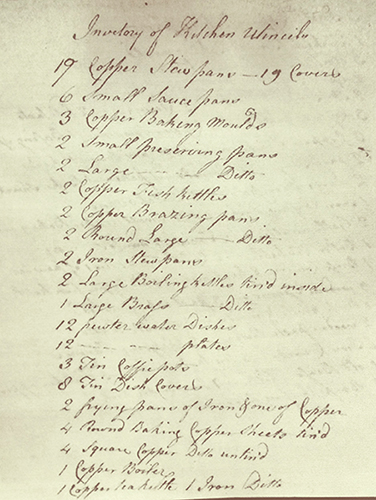

In 1793, Jefferson resigned from the secretary of state position and wanted to retire to Monticello. Coincidentally, Chef Hemings also wanted to retire—from being a slave. He asked Jefferson to free him, and Jefferson agreed under the condition that Hemings would teach others at Monticello how to cook, drawing on his accumulated knowledge and recipes that he had learned in France. This certainly would have saved Jefferson the expense of training another slave, as well. Hemings accepted this condition and requested that Jefferson draw up a formal agreement on paper, perhaps showing that he didn’t fully trust Jefferson. Thus, Hemings began a three-year culinary school for a select few cooking in the Monticello kitchen.44 Only two of Chef Hemings’s recipes exist to this day—though neither in his own hand—and they are both dessert recipes, one for chocolate cream and the other for “snow eggs.” The one extant document in his handwriting is an “Inventory of Kitchen Utensils” in the Monticello kitchen, a list that he created in 1796.

Inventory of kitchen utensils at Monticello, written by James Hemings, n.d. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Having fulfilled his obligations, James Hemings was freed in 1796 and immediately departed for Philadelphia. In 1797, Jefferson visited that city and spotted Hemings, later writing of their encounter, “James is returned to this place, and is not given up to drink as I had been informed. He tells me his next trip will be to Spain. I am afraid his journeys will end in the moon. I have endeavored to persuade him to stay where he is, and lay up money.”45 After some negotiation through a third party, Jefferson persuaded Hemings to return to the Monticello kitchen in 1801, but Hemings stayed only forty-five days. Had Hemings continued his professional relationship with Jefferson, he would very likely have been tapped to be Jefferson’s White House chef. Tragically, that day would never come. William Evans informed Jefferson in a 5 November 1801 letter that Hemings had died in Baltimore: “The report respecting James Hemings having committed an act of suicide is true. I made every enquiry at the time this melancholy circumstance took place. The result which was, that he had been delirious for some days previous to his committing the act, and it was the general opinion that drinking too freely was the cause.”46 We have no inkling of the demons that drove James Hemings to drink. While his memory lived on in those who knew him, there is nowhere near as much written about him as there is about Hercules. Any descriptions of what he cooked for Jefferson in Paris, New York, Philadelphia, or Monticello wait to be discovered—or may be entirely lost to history. Thus, a most interesting life came to a tragic end, and we are left to wonder, “What if?”

When he became president, Jefferson needed someone to cook in the White House kitchen, but he was reluctant to have any African Americans on his culinary staff. As he wrote in 1804, “At Washington I prefer white servants, who when they misbehave can be exchanged.”47 Honoré Julien—a white Frenchman who coincidentally filled in as Washington’s presidential chef when Hercules was removed from the position—was his first hire, and he was installed as chef de cuisine. Chef Julien would need additional help, so President Jefferson relented. As one Jefferson scholar wrote, “Despite having trusted enslaved domestics at Monticello, Jefferson brought only three slaves to the President’s House, a succession of apprentice cooks.” The first enslaved person to apprentice under Chef Julien was fourteen-year-old Ursula, who was named after her grandmother, a long-serving Monticello cook. Ursula had expertise in pastry making, but she lasted less than a year at the White House because she became pregnant. When she returned to Monticello, she rotated from kitchen work to fieldwork.48 President Jefferson would have to select someone else from the Monticello kitchen, and he ultimately decided to pick two enslaved women—Edith “Edy” Hern Fossett and Frances “Fanny” Gillette Hern. Fossett came to work in the White House kitchen in the fall of 1802, when she was fifteen years old. Four years later, she was joined by her enslaved sister-in-law Hern, who was eighteen years old when she arrived.

Earlier I noted how Chef Walter Scheib believed that the White House was modeled after a plantation “big house.” One big difference was in the kitchen. As plantation architecture scholar John Vlach notes,

By the first decades of the eighteenth century, it was already customary for the owners of large plantations to confine various cooking tasks to separate buildings located some distance from their residences. This move is usually interpreted solely as a response to practical considerations: the heat, noise, odors, and general commotion associated with the preparation of meals could be avoided altogether by simply moving the kitchen out of the house…. There were, however, other important if less immediately evident reasons for planters to detach the kitchens from their residences. Moving such an essential homemaking function as cooking out of one’s house established a clearer separation between those who served and those who were served.49

Fossett and Hern’s primary task was to help Chef Honoré Julien maintain President Jefferson’s sterling reputation for entertaining. President Jefferson was a culinary superstar in our early republic. He gets credit—probably too much—for introducing some popular European foods into American cuisine. Wealthy households were eager to mimic what the president served on his dinner table. A perfect example is macaroni and cheese—a dish that President Jefferson truly loved. By way of a backstory, Jefferson developed a macaroni mania while he served as the U.S. minister to France from 1784 to 1789. At the end of this diplomatic stint, Jefferson took great pains to have a macaroni-making machine sent from Naples to his Philadelphia residence. It is highly likely that Jefferson made sure that James Hemings learned how to make the dish during his “culinary school,” and that culinary knowledge was passed on to the other Monticello cooks. The earliest recorded macaroni and cheese recipe appeared in The Forme of Cury cookbook printed circa 1390. This was the “go-to” cookbook for the royal courts of Richard II and Queen Elizabeth I, and the “macrows” recipe consisted of little more than pasta, (Parmesan) cheese, and butter.50 Hemings’s showed his French culinary influence by adding cream to the original macaroni and cheese recipe.

President Jefferson thought so highly of macaroni that he served it at a small dinner party he held at the White House on 6 February 1802. Reverend Manasseh Cutler, one of the dinner guests, started his recap of the evening in his diary with a note of disappointment before describing the whole meal: “Dinner not as elegant as when we dined before. Rice soup, round of beef, turkey, mutton, ham, loin of veal, cutlets of mutton or veal, fried eggs, fried beef, a pie of macaroni.” Cutler then struggled to describe the new-fangled food, “which appeared to be a rich crust filled with trillions of onions, or shallots, which I took it to be.” Then came the final verdict: “tasted very strong, and not agreeable.” A Mr. Lewis, presumably Meriwether Lewis of Lewis and Clark expedition fame, explained to Cutler that he had just eaten an “Italian dish” and that the “onions” were in fact pasta. Cutler felt much better about the ice cream dish served for dessert, though. In terms of after-dinner entertainment, the party “drank tea and viewed again the great cheese,” the latter being a two-ton piece of cheddar cheese that some Massachusetts dairy farmers sent to the White House as an inauguration gift for President Jefferson.51

We know from records of what he grew at Monticello that Jefferson incorporated many West African foods like benne (sesame seeds), black-eyed peas, and okra into his diet. As one historian notes, President Jefferson’s White House menus “varied seasonally with foods often brought from Monticello…. Soups, whatever the season, were routinely served; a presidential favorite was savory tomato with chopped fresh herbs. One of Jefferson’s prized desserts was a delicious crème anglaise–based queen of puddings filled with homemade damson [plum] preserves and covered with meringue.” In addition, although he actually ate a prodigious amount of meat, President Jefferson espoused a primarily vegetarian diet while in the White House: “‘The English eat too much meat,’ he once commented. ‘I have lived temperately eating little animal food.’”52

Thanks to noted Jeffersonian expert Lucia Stanton, one gets a real sense of what a typical day was like in the White House kitchen.

On April 3, 1807, in the enormous room under the north Entrance Hall, the kitchen staff kept the fires burning in a fireplace, an iron range, and a stew-stove. Sandy the scullion filled a scuttle with charcoal for the latter, where pots of coffee and hot chocolate sat on grates above its cast-iron stewholes. After Fanny Hern scattered corn for the hens and ducks in the poultry yard and gathered up the new-laid eggs, she met the cart of Miller the dairyman and carried in the day’s milk and cream. Edy Fossett was preparing the breakfast breads, while Julien and Lemaire put their heads together to settle on a menu for dinner. Mary Dougherty was on her way to the cupboards to get linens for the breakfast table…. While Jefferson, James Madison, Albert Gallatin, Henry Dearborn, and Robert Smith discussed impressments on the high seas, steam rose from copper stewpans of soup and beans in the kitchen and from a copper boiler in the wash house in the west dependencies wing, where Biddy Boyle wrestled with sheets and pillow cases. Julien directed Edy Fossett in putting together his specialty of the day, “partridge with sausages & cabbage a French way of cooking them.” Revolving on the roasting jack before the hearth was a quarter of bear that Lemaire had purchased at market six days earlier. He was anxiously watching Fanny Hern stir an egg custard for the centerpiece of the dessert course.53

A similar scene played out several times during the Jefferson presidency, for Jefferson extensively used his dinner table to woo friend and foe alike.

Life outside of the White House kitchen—but still inside the White House basement—was another matter for Fossett and Hern. The White House basement was the live-in slaves’ “world,” an arrangement that wasn’t unusual for urban slaves and servants in wealthy households. As an urban slavery historian noted,

These [slaves] generally lived where they worked, not so much because the wages were low, but mainly because of great difficulties in getting to work in the mornings; for colored neighborhoods were far away and the working days were long and hard. Sleeping quarters were generally spare places in the attics, basements and about the stables and barns, so that the men could feed the horses easily in all kinds of weather. House servants always lived in the house so that they could rise early and start the fires and have the old coal stoves hot by the time the white people came down to breakfast.54

Apparently, Fossett and Hern lived at the White House for almost the entire year, even though President Jefferson returned to Monticello during the summer months. At first, this seems odd since Monticello was not a great distance away, and transporting Fossett and Hern to their home shouldn’t have been too burdensome. There are four factors in play here that may explain the president’s behavior.

First, Fossett and Hern had the primary task of meeting the needs of White House staffers. As Monticello historian Leni Sorensen explains, “Edith and Frances didn’t come home to Monticello when Thomas Jefferson did. He left them in D.C., probably because the White House was not completely abandoned when Jefferson left. There was always some staff that needed meals prepared for them.”55 Second, President Jefferson wasn’t wholly dependent on Fossett and Hern’s cooking because he had Peter Hemings and other enslaved cooks back at Monticello who could prepare top-notch meals. Third, as we learned earlier, slavery was legal and thrived in Washington, D.C. Thus, Jefferson didn’t worry about emancipation laws like those that existed in France and Pennsylvania. What’s unclear from the historical record is how closely Fossett and Hern’s movements were monitored. In all likelihood, and unlike the other professional staff, these women remained at the White House. And the fourth and final factor is that President Jefferson could not have cared less about their wants and desires to be reunited with their entire families. They existed for only one purpose—to serve him or others as he directed. Nothing else about his enslaved cooks was of real consequence to him.

During his two terms, a number of familial events highlighted the human drama unfolding in the White House basement. Fossett and Hern surely ached from long work hours and fretted about the frequent illnesses of their young children. During the summer months, the White House basement regularly flooded after a good rainstorm, and the increased risk of contracting a disease took a serious toll. “The presence of young children (of the Doughertys and the enslaved cooks) meant the dreaded diseases of infancy stalked the cellars of the mansion,” Lucia Stanton observes. “A boy died in Jefferson’s absence in the summer of 1802, and whooping cough carried off Fanny Hern’s child in November 1808…. Of at least five children born in the President’s House to the Monticello cooks, only two, James and Maria Fossett, survived to adulthood.”56

If both of these enslaved women were omnipresent at the White House, how does one explain their pregnancies? It turns out that the long marital separations caused by their White House tenure were occasionally interrupted by visits from their husbands.

Fanny Hern was able to see her husband for a day or two, at intervals. David Hern, a wagoner, journeyed alone to the Federal City twice a year, transporting plants and supplies between Monticello and the President’s House. Nevertheless, as former Monticello overseer Edmund Bacon recalled, they got into “a terrible quarrel,” Jefferson was “very much displeased,” and Bacon was summoned to the capital to take them to Alexandria for sale. When the overseer arrived, the Herns “wept, and begged, and made good promises, and made such an ado, that they begged the old gentleman out of it.” Edy Fossett’s husband, Joseph Fossett, made an unauthorized journey to Washington when he heard disturbing news from John Freeman or Jack Shorter, soon after their arrival with the president at Monticello in July 1806. The enslaved blacksmith left his forge and set out on foot on a road he had never before taken.57

As soon as President Jefferson found out about Fossett’s unauthorized visit, he ordered a hot pursuit to bring Joseph back to Monticello. Although love drove these husbands to take tremendous risks to see their wives, President Jefferson was oblivious to how his enslaved workers showed their family values.

In March 1809, Jefferson’s presidency ended, and Fossett and Hern returned to preside over the Monticello kitchen for years to come. According to Stanton, the former president and his guests were well pleased: “During the years of his retirement, Monticello visitors praised the ‘half Virginian, half French style’ of the meals they prepared.”58 Fossett and Hern cooked there until Jefferson’s death in 1826. But after all of their years of service, Fossett and Hern did not ultimately get their just desserts. As Stanton writes, “Honoré Julien’s enslaved pupils, after running Monticello’s kitchen for more than 15 years, were both sold at the estate sale after Jefferson’s death. Fanny Hern and her husband were purchased by University of Virginia professor Robley Dunglison. Edy Fossett and her youngest children were bought by her free relatives. Her husband, Joseph, who had been freed in Jefferson’s will, continued to work as a blacksmith to pay for the purchase of his wife and children.”59

We know that the legacy of President Jefferson’s table, both at the White House and at Monticello, lived on through his extended family and reached its fullest expression in the publication of Mary Randolph’s book The Virginia Housewife in 1824. The progeny of the enslaved presidential cooks carried the torch as well. The most notable example is Peter Fossett, Edith Fossett’s son, who was born at Monticello in 1816 and eventually became a successful caterer and Underground Railroad conductor in Cincinnati, Ohio. Peter Fossett made so much money through catering that he retired early from that business, became an ordained minister, and ultimately became known as the “Father of Ohio Baptists.”60 This was quite a feat for an African American man in nineteenth-century America. However, for most African Americans living in the nation’s capital, racial progress turned into regress as the century advanced. Two events effectively describe D.C.’s deteriorating race relations from two distinct vantage points: a well-known race riot and a daring, unprecedented escape attempt.

The event that locals would later call the “Snow Riot” happened in August 1835. An eighteen-year-old enslaved African American named Arthur Bowen was arrested and jailed for the attempted murder of the white woman who owned him. A lynch mob formed at the jail to execute the accused, but the police intervened.61 Author Jefferson Morley wrote a detailed account of the event:

Prevented by the police from gaining access to Bowen and [a white abolitionist named] Crandall, they redirected their anger toward Mr. Beverly Snow’s popular Epicurean Eating House, located nearby at the corner of Sixth Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW. They ransacked the restaurant, destroying furniture and breaking liquor bottles, forcing Snow to flee the District. After looting Snow’s restaurant, they continued their rampage by vandalizing other black-owned businesses and institutions, including Rev. John F. Cook, Sr.’s church and school at the corner of 14th and H streets, NW. Fearing that the mob would come after him, Rev. Cook fled to Pennsylvania. The impact of the Snow Riot lasted far beyond the few days of violence. As one of a number of clashes in the 1830s and 1840s, it was emblematic of the continued centrality of slavery in the nation’s capital.62

Despite the deadly consequences if caught, enslaved people were ever vigilant for opportunities to escape to freedom. The most spectacular opportunity, and the second example showing D.C.’s poor race relations, came during the Franklin Pierce administration. At dawn on 16 April 1848, several wealthy Georgetown families awoke to a tremendous surprise: all of their slaves had disappeared sometime the night before. A range of thoughts must have raced through their minds and emotions through their hearts, for they now witnessed the impossible—a mass slave escape had occurred. Slavers were accustomed to individuals or small groups attempting to get away, but never before had such a large number of enslaved people pulled off a coordinated disappearing act. This episode came to be known as the “The Running of 1848,” but I think this title is a misnomer. When those wealthy families faced the prospects of doing their own cooking and work—or at least of having to pay someone to do those tasks—the event is best described as “The Panic of 1848.”

Sometime the night before, seventy-six fugitive slaves and three white crewmen slipped out of Washington, D.C.’s harbor, and they sailed down the Potomac River aboard the schooner Pearl.63 The night was calm, and only the current propelled the ship downstream. After traveling about half a mile, the Pearl was stalled by the incoming tide and had to anchor. Near dawn, a fresh breeze arose from the north, and the ship and her passengers once again headed north, toward freedom. At the mouth of the Potomac River, the Pearl encountered strong northerly winds that prevented it from sailing up the Chesapeake Bay, and again it anchored, causing the passengers to lose even more of their head start.

A local African American man who was aware of the escape plan snitched on the others.64 As a result, around noon on the following day, the steamboat Salem, with about three dozen armed white men on board, hurriedly left Washington in hot pursuit of the fugitive ship. Fourteen hours later, as the passengers and crew on board the Pearl slept, the Salem caught up. After all of the extensive planning and being so close to freedom, the enslaved passengers’ hearts certainly sank as the Salem’s armed men boarded the Pearl and awakened its captain—a white abolitionist named Daniel Drayton. Since they were unarmed, Drayton advised the Pearl’s crew and passengers to exhibit restraint and not resist. Drayton, Edward Sayres (the Pearl’s owner), and Chester English (Drayton’s helper) were taken aboard the Salem for questioning, and everyone else remained on the Pearl as the steamer towed it back to Washington.

The daring escape attempt made national headlines, and its fallout rippled far beyond Georgetown. Paul Jennings, a formerly enslaved body servant for President James Madison, and Daniel Webster, a sitting U.S. senator from Massachusetts, had secretly helped plan the getaway, but they were never charged with any crime for their involvement. The plight of two young sisters, Emily and Mary Donaldson, who were involved in the attempted flight inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe, in part, to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Ultimately, the unsuccessful escapees were returned to work in the homes of their masters or sold into slavery elsewhere.65

Yearning for freedom was not limited to the streets of D.C. and Georgetown; it was also felt by those who worked within the walls of the White House kitchen. One of the most pernicious justifications for slavery was the supposed existence of the “happy slave.” This falsehood asserted that African Americans preferred and enjoyed slavery in an alien, but civilized, Christian nation rather than being free in the savage, pagan country that they once called home. For our purposes, the relevant permutation of the happy slave stereotype was that an enslaved cook should feel “honored” to have the privilege to cook for the most powerful person in the country—regardless of the circumstances. Yet, the jarring, internal inconsistency of the term “happy slave” did not stir the presumption of privilege so established in the minds of many white people or cause them to reassess the status of African Americans in American society. Few accounts captured this juxtaposition more perfectly than this remarkable conversation transcribed in an article titled “A Modern Pharaoh,” which appeared in the Liberator—a widely read, controversial antislavery newspaper founded by noted abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison:

Mr. ——. to the Colored Man. Are you a free man?

Colored Man. No, Sir, I am a slave!

Mr. ——. Well, I suppose you do not care for that—you must be happy and contented in such a situation as this, and withal, a slave to the President; are you not?

Colored Man. I do not know, Sir, why you should ask me such a question, or suppose any such thing.

Mr. ——. Why, it is because we at the North often hear our southern men, and some northern men, too, who have travelled at the South, say “the slaves are very happy and contented,” and much better off than free colored people.

Colored Man. I don’t know how that can be, Sir,—that a man as a slave can be better off than a free-man, seems impossible. I guess if they had to take my place, and be hired out by their master, as I am here to PRESIDENT TYLER, for $30 a month, and receive only $3 of it to support their families, as I do, they would not think their condition was so mighty nice.

Mr. ——. How many slaves has President Tyler?!!

Colored Man. Only four, Sir, at the white house. Did not know how many he had elsewhere.

Mr. ——. Have you a wife?

Colored Man. Yes, Sir, in Virginia; I have not seen her for months.

Mr. ——. Do the slaveholders ever separate husbands and wives, then—and families?

Colored Man. Certainly, Sir, whenever they choose. Two of the slaves of the President have not seen their wives since the President came to Washington. And they often sell them forever apart!!66

Such was life for the “happy slave.” Fortunately, by the time President Abraham Lincoln arrived at the White House, hope was building. As one survey history noted, “Washington has been from the first a kind of showcase city. Abolitionists, temperance advocates, zealots and reformers of every stripe made their mark here. The District was the first place where the domestic slave trade was abolished by federal legislation, the first place where slaves were emancipated, the only place where slave owners were recompensed by the government.”67

President Zachary Taylor was the last known chief executive to bring his own slaves to Washington, D.C., and have them take up residence in the White House. Presidents Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan didn’t own slaves, but they may have used loaned slaves to handle the domestic White House duties during their administrations. Though President Lincoln ended the White House’s dependence on slave labor, his domestic staff did not fully escape slavery’s legacy. As historian John E. Washington wrote, “When Lincoln came to Washington he found that in the White House nearly every servant could trace his ancestors from slaves who had grown up as house servants.”68 One of President Lincoln’s greatest accomplishments for race relations was subtle. He simply treated the African Americans who worked for him with dignity—something that had not happened in decades. Rosetta Wells, a seamstress in the Lincoln White House, remembered “that [President Lincoln] treated the servants like ‘people’ and would laugh and say kind things to them, and that because he was President he wasn’t ‘stuck up,’ and things had not gone to his head.”69

One of those White House workers whom President Lincoln is on record as having treated well was Mary Dines. Dines cooked for the Lincolns when they would retreat to the Old Soldiers’ Home in upper northwest Washington, D.C. Her birth date and year is currently unknown, but we do have some great details about her life. Dines was born in slavery on a farm in Prince George’s County, Maryland. Dines’s master was a wealthy bachelor who, reportedly, rarely beat his slaves. Upon his death, Dines was sold to a family in Charles County, Maryland, that was much harsher with punishment. Dines somehow ingratiated herself with the new master’s white children, and they secretly taught her how to read. With that education, she plotted her eventual escape to Washington. She fled utilizing the help of friendly slaves, hiding in hay wagons and staying at “stations” along the Underground Railroad. She eventually made it to a contraband camp near present-day Howard University. In this camp, Dines quickly made a reputation with her singing ability, eventually becoming “the leading soprano of the camp” and, thanks to her secret education, “also the principal letter writer” for the illiterate elders in the camp.70

President Lincoln frequently passed this camp en route to the Old Soldiers’ Home from the White House. Sometimes he would stop and talk with people there. During one of Lincoln’s visits, Dines was tapped to be an impromptu choir director, and though incredibly nervous, she led the gathered throng in singing songs like “Nobody Knows What Trouble I See, but Jesus,” “Every Time I Feel the Spirit,” “I Thank God That I’m Free at Last,” and “John Brown’s Body.” President Lincoln was moved to tears, for he “was very fond of the hymns of the slaves and loved to hear them and even knew most of them by heart.” The next time President Lincoln visited the camp, he expressly asked for Dines to lead another extended singing session. It’s not clear how Lincoln found out that she could cook, but she would eventually render such services at his summer retreat from the White House.71

As historian Matthew Pinkser explained, “Originally known as the Military Asylum, the Soldiers’ Home was an institution created in the early 1850s for disabled army veterans who could not support themselves…. The cottages at the Soldiers’ Home offered an attractive alternative to the White House, especially in hot weather, because they were well situated on cool, shaded hills.”72 President Buchanan was the first president to use this retreat and likely recommended it to President Lincoln. Dines was cooking for the Lincolns in this location by 1862, and she was quickly beloved by the Lincolns and the federal troops guarding the location. Dines probably endeared herself to Lincoln by making his favorite dish of cabbage and potatoes, and she curried favor with the troops by giving them the leftovers from the president’s table. During her cooking stint, the troops presented her with a dress to show their gratitude.

Old Soldiers’ Home. Washington, D.C., 2015. Author’s photograph.

Even under the unimaginable weight of waging a war and implementing emancipation, President Lincoln still had to deal with domestic matters such as a grumbling staff. Days after firing the rebellious Union army general George McClellan, President Lincoln wired First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln to ask for advice: “Mrs. [Mary Ann] Cuthbert & Aunt Mary [Dines] want to move to the White House because it has grown so cold at the Soldiers’ Home. Shall they?” Willard Cutter, one of the guards, wrote in a letter contemporaneous to the president’s telegraph that Dines “had already told him that she would be gone in a matter of days.”73 Dines’s request was apparently granted, for she did cook at the White House for a short period of time. But by the next summer, she was no longer working for the Lincolns. Pinkser notes, “What happened that summer to Mary Dines is not clear…. She might have run into trouble with Mary Lincoln, perhaps over her habit of providing meals to the Soldiers who guarded the cottage. The first lady had always been notoriously hard on her domestic help…. Or perhaps the contraband singer, caught up in the spirit of post-emancipation Washington, might have tried something new in this year of freedom.”74 Eventually, Dines was reinstated as the retreat’s cook in the fall of 1864, and in no time she relayed Mrs. Lincoln’s concerns for her husband’s safety to other members of the domestic staff.75

Lincoln’s gradual dismantling of legalized slavery in Washington, D.C., and the rest of the nation endeared him not only to his staff but also to millions of African Americans and white abolitionists. Those executive actions to end slavery also ushered in an era where independent, free-labor culinary professionals ruled the White House kitchen. And as hope swelled in the hearts of millions, the White House kitchen itself became a symbol of hope. Haley G. Douglass, one of Frederick Douglass’s grandsons, recorded the following anecdote:

It was the custom of Lincoln to sit at the window while reading a book or paper and occasionally gaze out of it. One evening, Lincoln called his messenger and said, “William, who is that old colored man outside with an empty basket on his arm? I have noticed him for some days, as he comes regularly, and leaves with the empty basket. Go downstairs, get him and bring him up here to see me.” The command of the President was instantly obeyed and in a few minutes the old man was hobbling into the presence of his Emancipator. Embarrassed and too full of emotion to speak a single word, he endeavored to say “Good evening,” but just could not get it all out.

Realizing the nervousness of the poor old man, as he was trying to get himself together, Lincoln said, “Well Uncle, I’ve seen you coming here for several days with your empty basket and then in a few minutes you go away. I’ve waited to see if you would come again and if you did I intended to send for you to learn your story. What can I do for you?” “Thank you, sir,” he said. “You know Mr. Lincoln, I heard that you had the Constitution here and how it has provisions [another word for food] in it. Well, as we are hungry and have nothing to eat in my house, I just thought I’d come around and get mine.” After a hearty laugh Lincoln told Slade to carry him downstairs to the kitchen and fill his basket. The grateful old fellow departed bowing low with gratitude and thanking God, and Lincoln too.76

The change in their legal status was an important pivot in the course of presidential foodways. Yet, the African American struggle to be fully integrated into American society had not ended with slavery’s demise. It merely changed the context of servitude.

In antebellum America, enslaved cooks used numerous protest strategies: doing the job poorly, sabotaging the equipment they used, poisoning their master and his family, or running away. Given the high profile that comes when cooking for the First Family, few of these strategies were practical for African American presidential cooks. Except for Hercules, who successfully escaped, and James Hemings, who negotiated his way out of slavery, most enslaved presidential cooks felt a kinship with Edith Fossett and Frances Hern, who were literally trapped in the White House basement.

After emancipation, African American presidential cooks felt trapped in a different way. Though they now had more liberty than ever, African Americans were free to choose a profession only from a very limited set of options. Having success in any other field besides a service occupation exposed them to violent retribution from racist whites on their physical bodies and their personal property. In essence, they continued to live in a “professional career ghetto” and were expected to work in jobs that served white people.

One thing that differed in post–Civil War America was that African Americans now had leverage. Whites had become so dependent on black cooks that few white hostesses could cook themselves, and there weren’t enough ethnic Asian or European immigrants to take the place of black cooks in the kitchen. As we’ll see in the next chapter, black cooks used their leverage, not always successfully, to negotiate for pay equity and better treatment. The fact that black cooks had the gumption to demand fair treatment or even decline to work in the White House kitchen evidenced how much things had changed.

Second in importance was the growing political clout of the black vote. Since the 1870s, Democrats and Republicans have alternately courted African American voters, whose vote could make a difference in close elections. The White House didn’t have its first African American presidential cabinet member until President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed E. Frederic Murrow as “Administrative Officer for Special Projects.”77 Before the 1950s, the potential white backlash that presidents faced from having a black appointee on the White House staff far outweighed the possible benefits. Many presidents took a pass on making such appointments. It was perfectly fine, though, for a president to have a black cook on his staff, and these cooks became de facto cabinet members. Knowing what their black cooks meant to the larger black community, presidents had to change the ways in which they related to African American cooks. Emancipation ushered in an age where, over time, presidents increasingly relied on their black cooks for advice on race relations. This is the time that the president’s kitchen cabinet began being built in earnest.

Recipes

HOECAKES

In his culinary biography of the Washingtons, Stephen McLeod writes: “Family members and visitors alike testified that hoecakes were among George Washington’s favorite foods. He invariably ate them at breakfast, covered with butter and honey, along with hot tea—a ‘temperate repast’ enjoyed each morning.”78 Try these instead of pancakes for a delicious breakfast.

Makes eight 4-inch hoecakes

1/2 teaspoon active dry yeast

2 1/2 cups white cornmeal, divided

3–4 cups lukewarm water

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 large egg, lightly beaten

Melted butter for drizzling and serving

Honey or maple syrup for serving

1. Mix the yeast and 1 1/4 cups of the cornmeal in a large bowl. Add 1 cup of the lukewarm water, stirring to combine thoroughly. If needed, mix in 1/2 cup more of the water to give the mixture the consistency of pancake batter.

2. Cover the bowl with plastic wrap and refrigerate for at least 8 hours, or overnight.

3. When ready to prepare, preheat the oven to 200°F.

4. Add 1/2 cup of the remaining water to the batter.

5. Add the salt and egg and blend thoroughly.

6. Gradually add the remaining cornmeal, alternating with enough additional lukewarm water to make a mixture that is the consistency of waffle batter.

7. Cover the bowl with a towel and set aside at room temperature for 15–20 minutes.

8. Heat a griddle on medium-high heat, and lightly grease it with lard or vegetable shortening.

9. Preparing 1 hoecake at a time, drop a scant 1/4 cup of the batter onto the griddle and cook for about 5 minutes, or until the bottom is lightly browned.

10. With a spatula, turn the hoecake over and continue cooking another 4–5 minutes, or until the bottom is lightly browned.

11. Place the hoecake on a platter, and set it in the oven to keep warm while making the rest of the cakes.

12. Serve the hoecakes warm, drizzled with melted butter and honey or syrup.

SNOW EGGS

As Damon Lee Fowler notes in Dining at Monticello, “This is classic French ouefs à la neige, which the enslaved cook James Hemings almost certainly learned in France. The recipe appears three times in the Jefferson family manuscripts, twice attributed to Hemings.”79

Makes 6 servings

5 large eggs

5–6 ounces (2/3–3/4 cup) sugar

2 tablespoons orange flower or rose water

2 cups whole milk

2 tablespoons sherry or sweet white wine

1. Separate the eggs, setting aside the yolks, and place the whites in a large metal or glass bowl.

2. Beat the whites with a whisk or an electric mixer fitted with the whisk until thick with froth.

3. Gradually add 4 tablespoons of the sugar and continue beating until the mixture forms firm, glossy peaks. Beat in 1 tablespoon of the orange flower or rose water. Set aside.

4. Stir together the milk, the remaining sugar, and the remaining flower water in a heavy-bottomed 2-quart saucepan.

5. Bring to a simmer over medium heat, stirring frequently to prevent scorching.

6. Reduce the heat to medium low.

7. Working in batches, drop heaping tablespoons of the meringue (no more than four at a time) into the pan and poach, turning once with a skimmer or slotted spoon, until set, about 4 minutes. The meringues will puff considerably as they poach but deflate to half the volume as they cool.

8. Lift them out with a slotted spoon or frying skimmer and drain briefly in a wire mesh colander or on a clean kitchen towel.

9. Transfer to a large serving bowl or individual serving bowls (about three per bowl) and poach the remaining meringue.

10. Whisk the egg yolks in a medium bowl until smooth and gradually beat in 1 cup of the hot milk mixture.

11. Slowly stir this back into the simmering milk and cook, stirring constantly, until the custard thickly coats the back of a spoon.

12. Remove from the heat and stir until it has cooled slightly.

13. Stir in the sherry or wine and strain the custard into a bowl through a wire mesh colander. Stir the custard until cool.

14. Pour the custard over the meringues and serve at room temperature, or cover and chill before serving.

BAKED MACARONI WITH CHEESE

Macaroni and cheese is often a glorious, goopy mess, but this recipe is closer to the earliest iterations of the dish. Thomas Jefferson served something like this to Rev. Manasseh Cutler when he dined at the White House on 6 February 1802.

Makes 6 servings

4 cups whole milk

4 cups water

1 pound tube-shaped pasta, such as small penne

6 tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into small bits

8 ounces imported Parmesan cheese or extra-sharp Farmhouse cheddar

1. Position a rack in the upper third of the oven and preheat the oven to 375°F.

2. Stir together the milk and water in a large pot and bring to a boil.

3. Add the pasta, stirring well, and return to a boil. Reduce the heat and simmer, stirring occasionally, until the pasta is tender, 8–12 minutes.

4. Lightly drain it in a colander (it should still be a little wet) and return it to the pot. Season with salt to taste and toss well.

5. Lightly butter a 2-quart casserole dish and cover the bottom with one-third of the pasta.

6. Dot with one-third of the butter and shave one-third of the cheese over it using a vegetable peeler or mandoline.

7. Repeat the layers twice more, finishing with a thick layer of cheese and bake until golden brown, 20–30 minutes.