7. Above Measure

You just don’t exist for all intents and purposes…. You are the most famous anonymous chef on Earth. Everybody talks about it, but nobody really knows about it.

WALTER SCHEIB, “Obamas Have a Habit of Inviting Celebrity Guest Chefs,” HuffingtonPost.com, 4 April 2010

On 19 December 1789, presidential steward Samuel Fraunces placed an advertisement in the New York Packet newspaper to fill the first presidential cook position: “A Cook is wanted for the President of the United States. No one need apply who is not perfect in the business, and can bring indubitable testimonials of sobriety, honesty, and attention to the duties of the station.”1 As we look back on the personalities met and the stories shared in this book, a historical update of the job announcement would probably read, “In addition to the duties described above, you will be called upon from time to time to fill any one of the following roles: baby sitter, barbecue pit master, civil rights adviser, comfort food enabler, confidant, controversy sparker, culinary artist, diet enforcer, diplomat, disaster relief worker, entertainer, pet detective/sitter, property clerk, school transporter, security detail, sommelier, and spin doctor.” With all of the additional duties, the at times high-stress environment, and relatively modest salary, one might wonder, “Who would want that job?” Mainly due to the prestige of the position, the short answer is “Plenty of people.”

I suspect that you have never heard about many of the culinary professionals mentioned in this book. Much of the venerable presidential history we consume omits these people primarily due to a mix of condescension and contempt toward African Americans on the part of the white historians who wrote the stories. Black people simply were not considered important enough to be part of the narrative. If blacks were mentioned at all, they were portrayed more like curiosities than people. More contemporary presidential history is worse in a unique way: the writers tend to be lazy. Even though information is now readily available to researchers, lots of writers seem to think that ignorance is too blissful to avoid. Life in a bubble can be very good, but a good story could be richer if more voices were added to give perspective. When food service in the modern White House is examined, I hope that reporters and writers will acknowledge that there are more cooks in the kitchen than the executive chef and the pastry chef.

Given the rich, previously hidden legacy that we’ve now made plain, the question must be asked: could an African American once again helm the White House kitchen? The resounding answer is yes! Any future president can make that choice. Fortunately, the question of culinary competence is no longer an issue. Don’t be fooled by the occasional “Where are the black chefs?” articles you may see in the mainstream media. Unlike in the days when Jacqueline Kennedy made European cooking de rigueur in the White House kitchen, thousands of African American chefs now working in private homes, hotels, resorts, and restaurants have the credentials and expertise to execute any cuisine they might be asked to prepare. Though few structural barriers exist to getting a job in the White House kitchen, several challenges do still persist. Much as it was in George Washington’s day, becoming a White House chef depends on a combination of skill, knowing (or working for) the right people, timing, and some good old-fashioned luck. Of these elements, knowing the right people is the most challenging, because it’s where the legacy of slavery and segregation has lingered the longest.

Despite decades of progress on civil rights and integration, many Americans still live, love, play, socialize, work, and worship with people who are like themselves. Unless people are intentional about diversifying their social circles, they tend to live in a homogeneous bubble. Thus, when a job opportunity arises, rather than cast a broad net to find the best person qualified for that opportunity (meritocracy), decision makers will often select someone in their own family (nepotism) or someone they know very well (cronyism). There are practical reasons for this. With some jobs, you want to be sure the person is up to the task and that he or she can be trusted, and there’s a short time to make a decision.

Here’s how this unintentionally affects the White House job prospects of a typical chef. Let’s say that those who aspire to be a White House executive chef do all they can to burnish their résumé so that they can get that job: they go to a great culinary school; they get a nice job as a sous chef in a well-regarded hotel or restaurant; they join the right professional associations and network like crazy until they have a decent public profile. Those chefs has made all of the right moves but may never be considered for the White House executive chef position unless they happen to be friends with someone with access to the First Family or to the White House staff or they have an opportunity to cook in the kitchen of a political elite. Before the 1960s, most African American presidential cooks took the latter route to the White House kitchen. Since then, the African Americans who serve as assistant chefs have predominantly come with hotel and military experience. It’s been two decades since the stars properly aligned and an African American was offered the White House executive chef position. That honor went to the late and acclaimed Chef Patrick Clark, and even he, as we’ll see in a moment, wasn’t a “perfect fit” for the job.

Patrick Clark grew up in Brooklyn, New York, the son of a professional chef (Melvin Clark) who took great care in his craft and even banned Velveeta from the family kitchen. Young Patrick, though discouraged from entering the arduous culinary profession by the very man whose cooking he admired, got his training the same place his father did—New York City Technical College. After obtaining further training in Europe, Clark went on to work and eventually helm some of the nation’s finest restaurants—Bice in Beverly Hills; Café Luxembourg, Metro (his first solely owned restaurant), Odeon, and Tavern on the Green in New York City; and the restaurants at the Hay-Adams Hotel in Washington, D.C. While at Tavern on the Green, Clark was named best mid-Atlantic chef by the James Beard Foundation in 1995.

These achievements led Chef Marcus Samuelsson to write posthumously of Patrick Clark that he was considered to be the “first Black celebrity chef.” Samuelsson added, “Clark helped make classical French cuisine—considered the bedrock of western cooking—more approachable when he created his own version of contemporary American cuisine with dishes like Horseradish Crusted Grouper and mashed potatoes, jerk chicken with sweet potato cakes, rack of lamb with fried white bean ravioli and salmon with Moroccan barbeque sauce.”2 Even celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain, who doesn’t suffer fools, admired Clark’s skills. “There was no one on the horizon we could see who could touch us,” he wrote in Kitchen Confidential.

Okay—there was one guy. Patrick Clark. Patrick was the chef of the red-hot Odeon in nascent Tribeca, a [New York City] neighborhood that seemed not to have existed until Patrick started cooking there. We followed his exploits with no small amount of envy … he was an American, one of us, not some cheese-eating, surrender-specialist Froggie. Patrick Clark, whether he would have appreciated it or not, he was our hometown hero, our Joe DiMaggio—a shining example that it could be done.3

Reportedly, Chef Clark was offered the White House job after the First Family tasted a salmon dish that Clark had prepared.4

In 1993, Clark started getting some influential customers. Black Enterprise reported, “Luckily for Clark and the Clintons, they are neighbors. The Hay-Adams sits directly across the street from the nation’s most famous residence. The Clintons frequently cart guests over to the hotel, making the Hay-Adams a venue of choice for Washington’s power dining.”5 Unbeknownst to Clark, several meals that he cooked were edible auditions for another job. The magazine continued, “Hillary Clinton, then still settling into the White House, offered Clark the job of White House chef. Clark turned it down. ‘I felt the White House would be too restrictive for me,’ Clark explains simply, adding that he had a three-year commitment to fulfill with the Hay-Adams Hotel, where he had just started as executive chef.”6 Another factor was a Freedom of Information Act–type secret: chefs can make a lot more money in the private sector than they do at the White House. Chef Walter Scheib told me that when he was hired in the 1990s, the typical salary could be anywhere between $50,000 and $70,000.7 When current White House executive chef Cristeta Comerford got the position in 2005, one newspaper reported her salary range as between $80,000 and $100,000.8 Clark thus turned down the position because he had “five kids and five college tuitions to save for.”9 At the time he was offered the White House gig, Clark was making $170,000 a year at the Hay-Adams, and in his next job at the Tavern on the Green in New York City, he made a reported $500,000 annually, including perks such as traveling around the world to do cooking demonstrations.10 Even though Clark met all of the criteria for being a White House executive chef, the “timing” was off. The job offer came at the wrong time in Clark’s career (he was too prominent) and family life.

One may be surprised to learn this, but filling a vacant White House executive chef position has long had its challenges. Long hours, high pressure, the small work space, and less pay offset the prestige factor. As the Clark example shows, the White House has to call at the right time in the career of a chef who is ascending. This by no means implies that White House chefs are not at the top of their game; I’m just noting that a highly accomplished veteran chef or television personality would have to give up a lot of money to serve his or her country in this capacity. “Sacrifice” doesn’t resonate as a rallying cry as it once did for those of the World War II era, the “Greatest Generation.” A hungry, talented chef “on the rise” faces an easier choice. Though Clark turned down the job, he was willing to help out whenever the president called on him.

That gave Clark the chance to act as guest chef for the meal of a lifetime: the state dinner held for South African president Nelson Mandela in October 1994. This function was one of the most consequential state dinners of the Clinton administration, honoring Mandela’s first visit to the White House since he was freed from prison in February 1990. According to Chef Scheib, rather than hosting the dinner in the usual State Dining Room, the Clintons held the dinner “in the East Room, because it was the room in which President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.”11 Scheib continued,

After our new protocol of featuring a dish that saluted the guest of honor’s homeland, we served a starter of Layered Late-Summer Vegetables with Lemongrass and Red Curry—loosely based on the South African style of food called Cape Malay cuisine, which combines ingredients of South Africa, seasonings of South Asia and India, and cooking techniques of Europe. We also invited a guest chef-collaborator to this evening, African-American chef Patrick Clark … with whom we conceived the main course, Halibut with a Sesame Crust and Carrot Juice Broth.12

After the initial consultation on the Mandela state dinner menu, the White House unveiled another surprise to Chef Clark—an invitation to prepare the meal. As Clark’s then sous chef Donnie Masterson recalled,

Patrick was honored to accept the offer [to cook the state dinner]. The White House later informed Patrick that [instead] he was to attend the dinner with his wife, Lynette. Patrick was as passionate as he was protective of his food, so he told the White House that he would feel more confident if his own chef [Masterton] were to execute his entrée. I felt unbelievably honored and proud to be representing not only the White House but also Patrick Clark…. I was Patrick’s chef, but he was always within arm’s reach of his food. On that night, he had to let go. I prepared a sesame and wasabi–crusted halibut. The meal was flawless. The next day, Patrick told me I had done justice to his dish and had made him proud.13

Republic of South Africa State Dinner menu card, 1994. Courtesy William J. Clinton Presidential Center/NARA.

Though Chef Clark didn’t actually cook the state dinner’s entrée, he savored that dish and the extraordinary moment.

Sadly, Chef Clark developed congestive heart failure a few years later and was desperately in need of a heart transplant. In 1997, the day after Thanksgiving, Clark checked into New York’s Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center to undergo a heart transplant. During his stay, he was so disappointed with hospital food that he had family members and loved ones sneak in cooking gear and food. At first, Clark kept a veil of secrecy over his clandestine culinary efforts that churned out dishes like grilled chicken with lemon and herbs and cauliflower steamed with garlic, but he later “sought attention because he hoped it would help force an improvement in the hospital food.”14 While in the hospital, Clark was diagnosed with another condition that prevented him from getting a new heart. He died two years later in Princeton, New Jersey.

In the nearly three decades that he cooked professionally, Patrick Clark, a dedicated husband and loving father, was acutely aware of the impact that he could make on American cuisine and of his place in American race relations. The New York Times reported, “‘He didn’t feel there was prejudice against him,’ said Stephen Moise, the executive sous chef at the Tavern [on the Green]. ‘But he could see how young African-American kids could feel that there was a lot against them, and he wanted to be an example of somebody who succeeded by working hard and believing in himself.”15 Bruce Wynn, an African American who worked as a pastry chef while Clark ran the Tavern on the Green, said, “He lived the flavor that he grew up on, and he spread that flavor.”16

Chef Marcus Samuelsson has been the only other notable chef of African heritage to act as guest chef for a White House state dinner. Samuelsson was born in Ethiopia, was adopted and raised by a Swedish family in Sweden, and then immigrated to the United States to start what would become a highly decorated culinary career. The White House described Samuelsson’s career in the press materials for the 24 November 2009 state dinner honoring the prime minister of India and his wife:

At the age of 39, Marcus Samuelsson has received more accolades than many chefs receive in a lifetime. A graduate of the Culinary Institute in Gothenburg, Samuelsson apprenticed in Switzerland, Austria, France and the U.S. In 1995 he was hired as Aquavit’s Executive Chef. Just 3 months later, Aquavit received a three-star review from The New York Times. Samuelsson was honored with the James Beard Foundation Award for “Rising Star Chef” in 1999 and “Best Chef, New York” in 2003. He was also celebrated as one of “The Great Chefs of America” by The Culinary Institute of America.17

Samuelsson obviously had the credentials to cook in the White House, but it took another special ingredient to get this dream cooking assignment that he didn’t seek.

In between ending his association with New York’s Aquavit restaurant and competing on Top Chef Masters, Chef Samuelsson got a call from a good friend. That good friend happened to be Chef Sam Kass, who was the personal White House chef for the Obamas at that time.

Sam was calling to ask if I’d be interested in creating the menu for the Obamas’ first state dinner. He told me he was speaking to a few other chefs, too, and that the state dinner was going to honor Prime Minister Manmohan Singh of India and his wife, Gursharan Kaur. Sam was asking if I’d make dishes that had a subtle Indian influence, and since the honored guests are both vegetarians, to make sure we could create a meal that would be very flavorful with no meat. The finalists would be chosen after evaluating each chef’s menu. It was the kind of call chefs dream of receiving, and in many ways it was far more important to me than anything that was happening on TV.18

Given his established reputation as an excellent chef and his friendship with Kass, Samuelsson was able to get on the short list. After a Sunday audition in his New York home for Kass, Samuelsson won the assignment and went on to make the state dinner. Though the attendees would describe the meal as memorable, the event itself was notable due to a couple of party-crashers whose ability to get past White House security and attend the dinner ultimately cost White House social secretary Desirée Rogers her job. In the end, Samuelsson’s experience is a useful roadmap for any chef who wants to be on the White House’s short list for guest chef. It’s all about being part of the conversation.

Aside from doing something illegal, actively and publicly campaigning is really the only “uncool” thing to do when seeking a White House chef job. This is a throwback to the early days of the presidency when the office was perceived as performing a duty for one’s country. In fact, when the Democratic Party chose him as its presidential nominee in the election of 1844, James Polk said in his acceptance speech that the presidency “should neither be sought nor declined.”19 In this context, working in the White House kitchen is about serving your country. As Walter Scheib put it, “None of these people have any idea what the job is about…. And they’re temperamentally not suited for it. You have to be a person who has a real heart of service, and it can’t be someone who needs to see themselves on camera.”20

Don’t get the impression that being a White House guest chef is always a “lovefest.” The politics of being a guest chef at the White House can get a little hectic, and the practice is not without its critics. Longtime White House pastry chef Roland Mesnier once said this on a panel of former White House staffers hosted by the White House Historical Association and broadcast on C-SPAN:

“I am the chef of the White House, who does everything for the family and guests, day in and day out, but the day that I can shine I’m told that somebody else is coming in,” he said. “I take it as a slap on the face as being White House chef.” He compared it to him asking to be President for a day. “I don’t believe in that, and I never will, because this is my job, and I would like to shine once in a while—and this is my chance.”

Mesnier added that these chefs were doing it for self-promotion and probably would decline the chance if they had to keep their collaboration secret.21

Scheib underscored that point when speculation was rampant in 2008 about who would be the next White House chef, and many were clamoring for a celebrity chef or someone with an agenda. Chef Scheib said of agenda-driven chefs, “I get a kick out of all these people saying the No. 1 thing should be green, or sustainable or this, that or the other thing. They’re missing the point. It’s not about advancing your agenda. It’s not about building your repertoire. It’s not about getting your business promoted. It’s about serving the first family, first, last and in every way. That’s the only job.” Mesnier underscored this point: “Celebrity chefs, in my book, are not chefs. They’re entertainers. All these people on TV? Forget it.”22 One can tell that he’s not a fan. Another path to the executive chef position is for a future president to choose someone currently on staff. That was the case for White House executive chef Cristeta Comerford, a Filipina, who began working for the White House in 1995 and then got promoted when Scheib departed in 2005.

The general public tends to not hear much about assistant chefs, let alone the kitchen stewards, but Adam Collick was thrust into the spotlight thanks to First Lady Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move!” initiative. Let’s Move! was formally launched on 9 February 2010 with the following mission:

Let’s Move! is a comprehensive initiative, launched by the First Lady, dedicated to solving the challenge of childhood obesity within a generation, so that children born today will grow up healthier and able to pursue their dreams. Combining comprehensive strategies with common sense, Let’s Move! is about putting children on the path to a healthy future during their earliest months and years. Giving parents helpful information and fostering environments that support healthy choices. Providing healthier foods in our schools. Ensuring that every family has access to healthy, affordable food. And, helping kids become more physically active.23

Let’s Move! sparked celebrities, chefs, community leaders in all sectors, doctors, parents, and teachers to get involved with this effort. Though its main objective was to have an impact on children, the initiative has had a rippling effect that goes all the way to the White House kitchen, particularly with Collick.

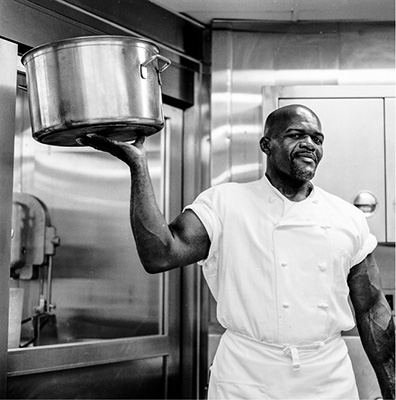

Collick became a Let’s Move! role model to the entire White House staff. Collick is a good-sized man, but he saw an opportunity to be healthier by eliminating extra calories. He eased up on drinking and traded “three 20-ounce cups [of coffee] topped with whipped cream drizzled with chocolate syrup” a day for calorie-free water and decided to eat dessert only a couple of times a week instead of with every meal. Those dietary changes coupled with exercise caused Collick to lose thirty pounds, which made him “a de facto coach to colleagues battling the bulge.” He told the Associated Press in an interview that appeared in the Washington Post, “Once you see the changes in your body and the way you feel, it’s going to make you want to keep doing it.”24 The amazing thing is that Collick did all of this while surrounded by serious temptations. The article continued:

Overdoing it is easy as a chef in a place where there are few food-free functions—ranging from receptions and dinners for hundreds of visitors to lunch for President Barack Obama and a guest in his private dining room off the Oval Office. One occupational hazard for the chefs is having to taste the food during all stages of preparation to check the flavorings, a seemingly simple task that when performed again and again every day can jeopardize anyone’s well-intentioned efforts to eat right.

Adam Collick, White House kitchen steward, 2003. Courtesy George W. Bush Presidential Center.

If not careful, Collick said, the chefs could easily eat an entire meal just by tasting their way through the work day.25

I’m sure any cook can relate to how remarkable Collick’s accomplishment is.

In the 1960s, there was a popular saying that I believe needs reviving: “Plant you now, dig you later.”26 In this context, I wonder what seeds are being planted in the dreams of young people that might flower into a desire to work in the White House kitchen. First Lady Michelle Obama has planted seeds that reimagine how the White House connects with our national foodways. The first is the vegetable garden and beehive that now exist on the South Lawn. There have been presidential gardens before, particularly during the nineteenth century (on the site where the current U.S. Treasury Building sits), but never with the scope and fanfare this iteration got when ground was broken on 20 March 2009. Aside from provisioning the White House kitchen and local food banks and schools, Michelle Obama had a larger, metaphorical vision for the garden: “I wanted it to be the starting point for something bigger. As both a mother and a first lady, I was alarmed by reports of skyrocketing childhood obesity rates and the dire consequences for our children’s health. And I hoped this garden would help begin a conversation about the food we eat, the lives we lead, and how all of that affects our children.”27 Not surprisingly, given our polarized political environment, there has been mixed reaction to the White House garden—both lauded as a worthy endeavor and lambasted as a worthless expenditure of public resources. Regardless of political opinions, it’s hard to argue with her desire to focus on childhood obesity given its rising incidence or with the fact that children don’t recognize raw vegetables by sight or realize that potato chips come from potatoes.

Of course, another option is to cultivate and nurture in young people an interest in cooking. First Lady Michelle Obama created a tremendous platform when she created the Kids’ State Dinners in 2012 as part of her Let’s Move! initiative. In 2012 and every year since, fifty young people, representing their home states, enter a recipe contest to make a healthy food. The winners and their parents get to visit the White House and have a meal in the East Room. Of the now more than two hundred champions, I end this book by focusing on one of the past African American winners: Kiana Farkash of Colorado.28

Farkash wanted to cook ever since she was two or three years old, watching her mother, Maureen, who is a good cook in her own right. According to Kiana, her mom made “tasty” food, and Kiana wanted to be like her. In her early years, she was her mom’s “sous chef,” handing over ingredients and spices and asking questions as Maureen prepared things like tilapia with kale and rice. By the time she was five, she was able to cook on her own; she made scrambled eggs and grilled cheese sandwiches. It’s no surprise that a few years later, while surfing the Epicurious website, Farkash’s grandmother saw an advertisement to participate in something called the “Kids’ State Dinner” and suggested Kiana enter the competition. Farkash asked for further explanation and blithely replied to her grandmother, “I’ll think about it.” Farkash decided to go for it and devised a recipe for grilled salmon with farro and a warm Swiss chard salad. All of the other ingredients pivoted off the Swiss chard, since her family garden was full of it. In addition, she paired her dish with a tropical fruit smoothie because she thought “kids would like something sweet.”

Sometime later, Farkash’s mom got an e-mail from the White House informing her that Farkash had won, and they both started jumping up and down with excitement. On 18 July 2014, Farkash, along with the other winners, enjoyed a private tour of the White House and its garden, special talks by Michelle Obama and White House chef Sam Kass, a surprise appearance by President Obama, a special performance of The Lion King, and participation in television interviews. On top of that, Farkash was one of two kids picked to help the White House kitchen chefs with plating the dishes that were served at the dinner. (She put microgreens on the spinach frittata.)

Michelle Obama hoped that the Kids’ State Dinner, as an adjunct of the Let’s Move! initiative, would be inspirational. At the very first dinner, she remarked,

Let’s Move! is all about … all of us coming together to make sure that all of you kids and kids like you across the country have everything you need to learn and grow and lead happy, healthy lives. It’s about parents making choices for their kids—choices that work with their families, schedules, budgets and tastes, because there is no one-size-fits-all here; as parents we know what works for one kid in one household doesn’t work for the other kid in the same household. So we’ve got to be flexible. And it’s about kids like all of you doing your part to eat well and get active, which is an important part. We never want to underestimate the importance of getting up and moving. So stay active. Get involved in cooking delicious, good stuff—dishes like the ones we’re going to try today.29

Farkash certainly took those rallying points home with her, especially the ones on healthy cooking. She emphatically told me that “healthy food doesn’t have to sacrifice on taste.” She also brought home the aspiration to become a professional chef when she grows up. A White House chef, perhaps? “I don’t know if I could do that,” she said. “Don’t you have to audition?” I assured her that by the time she could be considered for that position, she’ll have the skills.30

Kiana Farkash at the 2014 Kids’ State Dinner. Courtesy Maureen Farkash.

In the meantime, I wondered what Farkash will do with her burgeoning talent, now that she is at the point where she’s creating her own dishes. She would love to cook a meal for the First Family, probably panseared cod with snow peas and curried rice—the latter inspired by a nice meal at Rasika, an Indian restaurant in Washington, D.C., recommended to her by her hotel concierge and which she found out the Obamas also love. I asked whom she would cook for if she could choose anyone in the world. Like other ten-year-olds, I expected her to list an actor, athlete, entertainer, politician—or someone with Kardashian in their name. No, Farkash said that she would like to “cook for a family who doesn’t know how to cook or who doesn’t have access to good ingredients.”31 Kiana is acutely aware of the growing problem of food deserts (areas where people lack access to healthy and affordable food, especially fresh produce) and malnourished, impoverished families. She knows kids whose main meal during the day consists entirely of junk food, and what the school offers is not much better. Don’t be surprised if for a high school community service project she ends up creating a farmer’s market in one of those food deserts. Farkash may wind up cooking for the president or advising the president on food policy—or may even be the president one day. As it should be, the sky’s the limit.

Only time will tell if Kiana Farkash, or another young person like her, will become a White House chef, but she already sees herself as a “change agent.” She can take inspiration in the legacy of the African American presidential chefs profiled in these pages. Even though they operated mostly out of public view, they asserted their humanity in ways that affected how presidents, First Families, White House staffers, the nation, and, in some cases, the world viewed African Americans. The term “kitchen cabinet” has traditionally been understood as an informal group of advisers and counselors whom a president consults when the need arises. Black chefs certainly participated in that role, and we now know how strong their agency often was and their importance to presidential history. They gave the most powerful chief executive of the United States of America a unique view of black life and black people. Through their work as culinary professionals, they confronted, contested, and ultimately creamed a racial caste system designed to keep them at society’s margins. Instead, over a daily table, they nourished our presidents to truly taste the desire of an entire people to fully participate in American society.

Recipes

SESAME AND WASABI–CRUSTED HALIBUT

Chef Patrick Clark developed this recipe for the 4 October 1994 White House state dinner honoring Nelson Mandela, then president of the Republic of South Africa.

Makes 4 servings

For the halibut

1/2 cup black sesame seeds

1/2 cup white sesame seeds

4 (7-ounce) halibut fillets

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Flour for dusting

2 tablespoons wasabi paste

1/4 cup plus 2 tablespoons olive oil

For the carrots

6 carrots, peeled

1 1/2 teaspoons cornstarch

2 tablespoons butter

Salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste

Ground nutmeg, to taste

Extra-virgin olive oil

12 sprigs chervil

To prepare the halibut:

1. Mix together the black and white sesame seeds on a plate.

2. Season the halibut with salt and pepper and dust the flat side of the halibut with flour.

3. With a spatula or small knife, spread the wasabi paste on the dusted side of the halibut, avoiding the sides of the fillet.

4. Lay the fillets, paste-side-down in the sesame seeds, pressing the fish into the seeds to ensure complete coverage.

5. Place on a plate, cover, and refrigerate until ready to cook.

6. Preheat the oven to 350°F. Heat the olive oil in a large, nonstick, ovenproof sauté pan over medium heat.

7. Place the fillets in the pan, crust-side-down and sear them until golden.

8. Turn the fillets over and place the pan in the oven for 4 or 5 minutes, or until cooked medium rare.

To prepare the carrots:

1. Scoop the carrots with a melon baller, reserving the scraps.

2. Blanch the carrot balls in salted water for 3 minutes, drain, and shock in ice water.

3. Remove from the water and set aide.

To prepare the carrot broth:

1. Purée the carrot scraps in a food processor and strain through a fine-mesh sieve.

2. In a small bowl, mix 4 tablespoons of the carrot juice with the cornstarch to create a slurry.

3. Put the remaining carrot juice in a saucepan and bring to a boil, then lower the heat to a simmer and whisk in the slurry and the butter.

4. Transfer the broth to a double boiler and add the carrot balls.

5. Season with salt, pepper, and nutmeg and keep warm.

To serve:

1. Place each fillet in the center of a large, shallow bowl.

2. Spoon the carrot balls and the sauce evenly around the fish.

3. Drizzle a few drops of the olive oil into the broth and garnish with the chervil sprigs.

LAYERED LATE-SUMMER VEGETABLES WITH LEMONGRASS AND RED CURRY DRESSING

Former White House executive chef Walter Scheib created this side dish with seasonal ingredients available in the United States to pay homage to South Africa’s indigenous food culture. You’ll need 4 ring molds (3 inches in diameter and 2 inches high) for this recipe.

Makes 4 servings

For the dressing

1/2 tablespoon olive oil

1 tablespoon minced shallot

2 teaspoons grated garlic

2 teaspoons grated lemongrass (white base portion only; peel off outer layer before grating)

1 teaspoon finely grated lime zest

1 teaspoon red curry paste

1 teaspoon grated fresh ginger

1 makrut lime leaf (optional)

1/2 cup homemade or store-bought low-sodium chicken stock

1/2 cup unsweetened coconut milk

1 tablespoon honey

1/4 teaspoon fish sauce

For the vegetables

1 medium cucumber (about 4 ounces)

1/2 tablespoon salt

1 tablespoon seasoned rice vinegar

1 tablespoon chopped fresh dill

4 ounces butternut squash, peeled, seeded, and sliced 1/4 inch thick (about 1/3 cup sliced)

2 tablespoons olive oil

Salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste

2–4 small red-skinned potatoes (4 ounces), sliced 1/4 inch thick (about 1/2 cup slices)

1 medium zucchini (about 4 ounces), sliced 1/4 inch thick (about 1/2 cup sliced)

1/2 tablespoon minced garlic

1/4 cup uncooked corn kernels (fresh or frozen, thawed, and drained)

1/4 cup thinly sliced leek (white part only)

1 medium red bell pepper, roasted, skinned, seeds removed, and very thinly sliced

Crispy noodles, such as rice noodles, for garnish (optional)

4 sprigs Thai basil or regular basil, for garnish

To prepare the dressing:

1. Heat the oil in a small saucepan over medium heat.

2. Add the shallot, garlic, lemongrass, and lime zest and sauté until softened but not browned, 2–3 minutes.

3. Add the curry paste, ginger, and lime leaf, if using, and cook, stirring, for 2–3 minutes.

4. Add the stock, coconut milk, honey, and fish sauce.

5. Bring to a simmer and cook for 10 minutes.

6. Strain the mixture through a fine-mesh strainer set over a bowl, pressing down on the solids with a wooden spoon or spatula to extract as much flavorful liquid as possible.

7. Discard the solids and let the dressing cool to room temperature.

8. The dressing can be covered and refrigerated for up to 1 week. It will separate; whisk and warm it to reconstitute.

To prepare the vegetables:

1. Peel the cucumber, halve it lengthwise, scoop out the seeds, and cut it crosswise into 1/4-inch slices.

2. Put the cumber slices in a colander, toss with the salt, and set the colander in the sink to drain for 10–15 minutes to extract any excess moisture.

3. Pat dry with paper towels.

4. Stir together the rice vinegar and dill in a small bowl.

5. Add the cucumber, season with salt and pepper, and toss. Set aside.

6. Preheat a 12-inch, heavy-bottomed sauté pan over medium-high heat.

7. Brush the squash slices with 1/2 tablespoon of the olive oil, season with salt and pepper, add to the pan, and cook just until tender, 1–2 minutes per side.

8. Transfer to a baking sheet and set aside.

9. Carefully wipe out the sauté pan.

10. Brush the potato slices with a 1/2 tablespoon of olive oil, season with salt and pepper, add to the pan, and cook over medium-high heat until tender, 1–2 minutes per side.

11. Transfer to a baking sheet and set aside.

12. Wipe out the pan. Brush the zucchini slices with 1/2 tablespoon of the olive oil, season with salt and pepper, add to the pan, and cook over medium-high heat just until tender, about 30 seconds. (The zucchini is tender enough that you only need to cook the slices on 1 side.)

13. Transfer to the baking sheet with the squash.

14. Wipe out the pan. Add the remaining oil and heat it over medium heat. Add the garlic and sauté for 30 seconds.

15. Add the corn and leek and sauté just until al dente, about 3 minutes.

16. Layer the vegetables into the ring molds, in any order you like, so long as the zucchini is on top.

To serve:

1. Place a salad plate face down over a ring mold and invert the mold onto the plate. Repeat with the other molds.

2. Drizzle 2–3 tablespoons of the dressing around the ring mold on each plate, then carefully remove the mold.

3. Garnish with crisp noodles, if desired, and basil leaves. Serve.

GRILLED SALMON WITH FARRO, SWISS CHARD SALAD, AND A TROPICAL SMOOTHIE

Kiana Farkash won a trip to the White House with this recipe when she was just eight years old. “I made grilled salmon because it is one of my very favorite dishes,” says Farkash. “I made the salad because it is very colorful and it reminds me of spring. I like warm, tropical places, so I decided to serve this with a tropical breeze smoothie because it reminds me of our family trip to Florida. I used farro because it’s a healthy whole grain and I like the nuttier flavor it has!”

Makes 4 servings

For the salmon and farro

1 cup farro

2 tablespoons olive oil

4 salmon fillets (about 1 pound)

2 tablespoons herbes de Provence

Salt and pepper, to taste

Pinch of garlic powder

Pinch of onion powder

1 lemon, thinly sliced

For the salad

1/2 tablespoon olive oil

Bunch Swiss chard, roughly chopped

1 large carrot, julienned

1 large red bell pepper, julienned

1 tablespoon balsamic vinegar

Salt and pepper, to taste

Crumbled feta cheese, to taste (optional)

For the smoothie

1 cup orange juice

1 cup “lite” coconut milk

2 cups low-fat vanilla yogurt

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

2 frozen bananas

1 cup frozen cut mango

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground nutmeg

To prepare the farro and salmon:

1. In a large pot, boil 2 cups of water over high heat.

2. Add the farro and bring back to a boil.

3. Reduce the heat to low, cover, and simmer for 30 minutes, or until the grains are tender and all the water is absorbed.

4. Preheat the grill.

5. Drizzle the olive oil over both sides of the salmon fillets.

6. Mix the spices in a small bowl and sprinkle evenly to coat the salmon on both sides.

7. Grill the fillets for up to 5 minutes per side, depending on how thick the salmon is.

8. After flipping the salmon on the grill, place the lemon slices on the fish. Remove from the grill and keep warm in a 200° oven while you make the salad.

9. To serve, spoon a generous portion of farro on the plate and lay the salmon fillets on top of the farro.

To prepare the salad:

1. In a large pan, warm the olive oil over medium heat.

2. Add the Swiss chard and cook for 2 minutes.

3. Add the carrot and bell pepper and cook for 2 minutes more.

4. When Swiss chard wilts, add the balsamic vinegar and season with salt and pepper; sprinkle with feta cheese, if desired.

To prepare the smoothie:

1. Add the liquid ingredients to the blender first, and blend.

2. Add the rest of the ingredients.

3. Blend again and enjoy!