The Pacific Railway must be built by means of the land through which it has to pass.

Macdonald during “Manitoba” debate in Commons, May 1870

The execution of Thomas Scott changed the nature of the crisis from a possible civil war between the Métis and the Canadian government to a possible civil war among Canadians. From now on, French Canadians identified with Riel and the Métis, while English Canadians, above all the Orangemen of Ontario, identified with Scott. As for Macdonald, he not only had to look constantly at London, Washington and Red River, but now had also to keep a close eye on developments in his own backyard.

To this point, Quebecers had paid little attention to the West; it was a long way off and, to all but fur traders, was foreign. It had taken George-Étienne Cartier to grasp that the principal beneficiary of a transcontinental railway across the North-West would be Montreal, the country’s natural transportation and financial centre, thereby dashing the aspirations the Toronto Globe had expressed in December 1869: “We hope to see a great new Upper Canada in the North-West.” Ontario businessmen also counted on western grain getting to Britain by way of Toronto and the Erie Canal. Nationalists in Quebec still worried that the West, with its free land and rich soil, would attract habitants to move there to farm. That had always been the hope of the astute Bishop Alexandre Taché of St. Boniface, Riel’s original patron. But Quebec’s leaders wanted their people to stay home to ensure that the province remained overwhelmingly French; the newspaper La Vérité denounced emigration to the North-West as “a social calamity which all true patriots have a duty to fight with all legitimate means.”

When the trouble began in Red River, few Quebecers took any notice. Le Pays described its own position as “considerable indifference,” and L’Événement dismissed the Métis as “savage people … [whom] a few cases of beads would have satisfied.” Quebec woke up to the crisis only after Ontario had begun to seethe. Then, because Quebec saw Ontario as anti-Quebec, it was anti-Ontario rather than pro-Riel.*

Anger in Ontario was predictable, because one of its own had been killed by French-speaking Roman Catholics. The anger quickly escalated into something far more threatening—not just rage, but well-organized rage. Its forcing agents were bigotry and sectarianism, but patriotism also played a part; Scott’s murder catalyzed the first attempt to articulate a sense of Canada as itself, rather than as a collection of leftovers of British North America. The attempt failed, but it left behind footprints that others would follow later far more effectively.

In April 1868, a year after Confederation, a group of aspirant poets and journalists who admired D’Arcy McGee got together in Ottawa to talk about their country—what it was and where it might go. They gave themselves the title “Canada Firsters.” The best expression of these often naïve and confused ideas appeared in the Globe in a series titled “Our New Nationality,” by a Toronto lawyer and journalist, W.A. Foster. He made the first attempt to describe a distinct Canadian identity: “We are a Northern people … more manly, more real, than the weak-marrowed bones and superstitions of an effeminate South.” Others picked up this theme. Robert Haliburton, son of the author of the popular Sam Slick series, described Canada as “a Northern country, inhabited by the descendants of the north men.”

Out of manliness and northernness, these men believed, had come a North American quite distinct from Americans in the United States. For some Canada Firsters, idealism was the spur: William Norman called on Canada to “fulfill her destiny, to be an asylum for the oppressed and downtrodden people of Europe.” For others, it was bigotry: the popular historian George Robert Parkin observed that, unlike the “vagrant population of Italy and other countries of Southern Europe” that had come to the United States, Canada was composed of “the sturdy races of the North—Saxon and Celt, Scandinavian, Dane and Northern German.” George Denison, the scion of a United Empire Loyalist family and a military authority, believed that what Canadians needed to make themselves distinct was “a rattling good war with the United States.”*

The Canada Firsters would reach their peak in the mid-1870s, after the Oxford historian Goldwin Smith moved to Canada, joined the group and gave it credibility. Edward Blake was widely expected to become its leader, but ultimately refused. Not long afterwards, the movement petered out. In the meantime, however, this first attempt at pan-Canadian nationalism escalated the protests against Scott’s execution into a powerful popular cause.

John Christian Schultz and Charles Mair, the pair of counter-insurgents who escaped from Red River, were both Canada Firsters. They were intellectuals—Mair wrote two of Canada’s first works of poetry, Dreamland and Other Poems and Tecumseh, and Schultz produced a number of learned articles that would earn him membership in the Royal Society of Canada. They were also romantics, attracted to the West because they believed that Canada’s future lay there. Mair described it as “the garden of the world” in an article in the Globe. Later, both men championed the Indians: Mair called them “villainously wronged,” and Schultz argued in the Senate that the treaties negotiated with them were grossly unfair.

Yet when they lived in Red River, both men were detested by the Métis. Mair received a horse-whipping from an enraged Métisse after he wrote in the Globe that Métis wives had a habit of “biting at the backs of their white sisters.” Schultz, although bilingual and married to a Catholic, was deeply mistrusted by the Métis for his questionable business dealings as well as his leadership of the so-called Canada Party in Red River. Once they had made their harrowing escape across the border, the pair headed for Toronto, determined to arouse protests against Scott’s execution.

By a fateful coincidence, strong emotions already existed in Quebec. There, the dominant creed at this time was a particular form of Catholicism known as ultramontanism, a right-wing doctrine that looked to Rome for guidance in all matters secular as well as religious. Its leader was Montreal bishop Ignace Bourget, who rejected any notion of separation between church and state. The “Catholic Program” he persuaded the Quebec bishops to adopt encouraged priests to direct their congregations on which way to vote during elections. These priests told their faithful to note that heaven was bleu and hell rouge, these happening to be the colours of the Liberal rouges and the conservative, pro-ultramontane bleus.

Connections existed between this movement and Red River. Bishop Taché was an ultramontane (as was Riel) and, at the time of the uprising, he was in Rome for the First Vatican Council, at which the church promulgated the doctrine of papal infallibility. Two powerful, directly contradictory movements were now headed for a collision—the ultramontanes and the Orange lodges. One was passionately pro-Rome, the other pro—British Empire; one hierarchical and authoritarian, the other democratic and populist. Both were arch-conservative and narrow.

The inevitable explosion ignited on April 6, 1870, the day Schultz and Mair made their first appearance in Toronto. Earlier, the feisty Denison had issued a challenge: “Is there an Ontario man who will not hold out a hand of welcome to these men? Any man who hesitates is no true Canadian.” The Canada Firsters organized a rally at St. Lawrence Hall, and the mayor agreed to take part. When five thousand people tried to cram into the hall, the event was moved to the steps of City Hall, where more than ten thousand aroused citizens turned out. From then on, all the Orange lodges across Ontario were eager to assist Schultz and Mair. In succeeding rallies across the province, the rhetoric got ever wilder, with audiences shouting out, “Death to the murderers and tyrants of Fort Garry.” To keep the rage at fever pitch, Schultz took to holding up a piece of rope, claiming it had been used “to bind the wrists of poor, murdered Scott.”

From across the Ottawa River came the first angry response. The newspaper L’union des Cantons de l’Est remarked, “How much hatred there is in these Anglo-Saxon souls against everything which is French and Catholic.” L’Opinion publique denounced the “fanatical Upper Canadian press.”

These dragon seeds of a sectarian civil war had been sown at the very moment when the delegates from Red River were due to arrive in Ottawa. In the meetings to follow, Macdonald hoped to negotiate an agreement that would bring the North-West amicably into Canada.

Macdonald’s immediate challenge was that many in Ontario—Denison most particularly—suspected that to appease Quebec he would never send a military expedition to Red River to restore order. Conversely, many in Quebec suspected he would dispatch the troops precisely to crush their Métis kin. In fact, he had by now made up his mind that the expedition “must go,” while still telling Lord Carnarvon how important it was that the troops be “accepted, not as a hostile force, but as a friendly garrison.” For that to happen, a satisfactory settlement with Riel’s delegates was essential.

A separate issue was coming to the fore. Back in December, Governor General Lisgar had proclaimed an amnesty for all Métis involved in the uprising who had committed civil offences (such as breaking into Fort Garry and making use of HBC stores), provided they laid down their arms. Although the Métis had not put down their weapons, this technicality could be overlooked in normal times. But the times were abnormal. The Liberals, realizing how narrow was Macdonald’s manoeuvring room, began to insist that he declare unequivocally that no amnesty would be granted to Riel or to anyone involved in Scott’s death.

It was hard for Macdonald to hide his annoyance that so much damage had been done so unnecessarily. He told Adams Archibald, soon to replace McDougall as lieutenant-governor, that were it not for Scott’s execution, all parties would “acquiesce in the propriety of letting by-gones be by-gones.” For Macdonald, the only solution to the rift between the country’s founding European races—with French Canadians calling now for a general amnesty, while Ontario’s English Canadians insisted it exclude anyone involved in Scott’s death—was “Time, the great healer of all evils.” As for the amnesty issue itself, he would once again pass that responsibility back across the Atlantic to London on the grounds, true in law, if only just, that the North-West still belonged to Britain and not Canada.

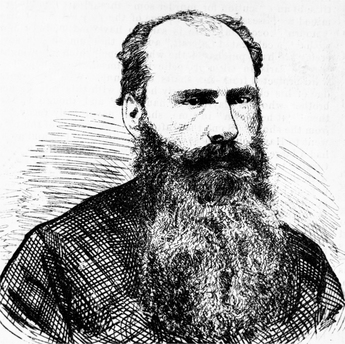

When the delegates left Red River on March 24, they had no idea of the furore awaiting them until their train neared Toronto. There were three of them: a judge, John Black; a saloon-keeper, Alfred Scott (no relation to Thomas Scott); and a priest, Father Noël-Joseph Ritchot. A big man with a waist-length black beard, Ritchot had come to Red River from Quebec as a missionary in 1862. Though quiet and gentle, he was awed by no one. He was Riel’s confidant and had acted as his adviser during the uprising. Ritchot always denied this, but at his funeral in 1905, a fellow-priest from the time, Georges Dugas, described Ritchot as “the soul of the movement,” adding, “It was he who launched it.” In the negotiations, Ritchot would prove exceptionally skilful and persistent, even though handicapped by speaking little English.

As Riel’s choice as a delegate to Ottawa, Father Noël-Joseph Ritchot won every round, from land for the Métis to making Manitoba a province, but for the last one—an amnesty for Riel. (photo credit 10.1)

Macdonald’s first task was to make certain the delegates reached Ottawa safely. He sent word that they should not stop in Toronto but continue to Ogdensburg, New York, where a private coach would bring them to the capital. Once they had made it to Ottawa, however, some Canada Firsters arranged for two of the delegates to be arrested on a warrant for murder. A judge released them, almost certainly at Macdonald’s direction. Thomas Scott’s brother, Hugh, then had a second warrant taken out. Again they were arrested and again released.

Finally, on April 25, all three delegates got together with Macdonald and Cartier in Cartier’s house in Ottawa. Ritchot insisted that the two politicians issue a declaration recognizing their visitors as representatives of the provisional government of the North-West. A version produced a day later referred to them only as “from the North-West.” Ritchot protested but settled for their being granted “official status.” He then declared that no negotiations of any kind could take place unless they made a clear statement that a general amnesty would be given for all offences committed during the insurgency. Macdonald responded that this decision would have to be made by the Imperial government, though he was certain it would be forthcoming. Ritchot accepted this response, even though Macdonald had actually committed himself to nothing. The subtleties of the language in translation no doubt escaped Ritchot and later led to prolonged charges and counter-charges between the two men.

When discussion turned to specifics in the bill of rights agreed on in Red River by the convention of elected delegates, Macdonald and Cartier found that Riel had unilaterally added last-minute demands, most notably that the region become a province rather than a territory—an idea the convention had specifically rejected because of the costs it would impose. But Macdonald and Cartier were ready to yield, and, in addition, quickly agreed to the demands for bilingualism and denominational schools. They also agreed to a special allotment of land for the Métis, an issue Ritchot would pursue with unflagging persistence. An initial offer of 100,000 acres grew to 1.4 million acres, including a special provision for the children of Métis families.

In gaining so much land for the Métis, Ritchot had done extraordinarily well—but not in one critical respect. Riel wanted a single huge block of land, which could serve as a kind of collective reserve for the Métis. What he was being offered were myriad small lots for individual Métis. At the public discussions back in Red River, Riel had made a most revealing statement: “We must seek to preserve the existence of our people.… Though in a sense British subjects, we must look on all coming from abroad [from Canada] as foreigners.” What he meant was that the Métis, as “a new nation,” had to live apart. Riel spelled this notion out in a letter he sent to Ritchot while he was in Ottawa: “Cette coutume des deux populations vivant separement soit maintenue pour la sauvegarde de nos droits.” In effect, Riel was asking for an Indian reserve while, simultaneously, retaining all the rights of other Canadians; in other words, status as a distinct society (though the notion did not then exist). It was too much, and Ritchot may have recognized that or simply not fully understood what Riel sought. This misunderstanding would be repeated more than a decade later in Saskatchewan, with explosive consequences. On both occasions, though, Riel recognized clearly that what was needed to try to secure the future of his people was not transfers of plots of land to individual Métis but rather a collective land settlement.

At this point in the negotiations, Macdonald and Cartier at last showed their own hand. They agreed to the demand that the North-West Territories come into Confederation as a province. Only a very small part of it, the size of PEI, would be called Manitoba—in Cree, “God who speaks.” Ottawa would retain ownership of the remainder of the territory and of the Crown lands within the mini-province. They would be used for national purposes—to develop a granary for the empire and as a buildingblock for a transnational railway. Otherwise, no deal was possible, because no Parliament would ever accept it. Having done so well on other matters, Ritchot agreed to these limitations. He did not know, however, that the British government had sent over an official, Sir Clinton Murdoch, to keep an eye on things, and that Murdoch had reported back his strong opposition to “an indemnity to Riel and his abettors for the execution of Scott.” Ritchot, unlike Macdonald, most certainly did know how much he had failed to win.

By the end of April, when the work was all but finished, Ritchot noted in his daily journal that Macdonald had failed to show up because “indisposed.” The accumulated strain had set him off on a prolonged binge. Cartier was left to settle the final details with Riel’s delegation, though Macdonald did reappear just before they were completed. (Of the delegates, Ritchot remained in Ottawa to argue for a blanket amnesty, Black left the country to return to his native Scotland, and Scott, who had been receiving secret commissions to tell Americans how the negotiations were proceeding, just vanished from the scene, initially moving to New York.)

The Manitoba Bill was introduced into the Commons on May 1, 1870, and attracted almost no debate. The Métis would get a great deal of land; the country would get a fifth province (enlarged a bit at the last moment)—a second bilingual one that, before long, would receive critical attention from the Orange Order. The federal government would get a huge reserve of Crown land. During the debate in the House of Commons, Macdonald explained the reason: “The land could not be handed over; it was of the greatest importance to the Dominion to have possession of it, for [financing] the Pacific Railway.” Cartier said the same thing more directly: because a railway was soon to be built across the prairies and on to the Pacific, “the Dominion Parliament would soon require to control the wild [Crown] lands.”

Manitoba came officially into existence on July 15, 1870. Its lieutenant-governor (also that of the now-reduced North-West Territories) was Adams Archibald, a Nova Scotian with no knowledge of the West, but intelligent, tactful and astute enough to take care that francophones held important posts in his administration. He was exactly the kind of proconsul Macdonald should have appointed a year earlier.

Later, Riel would claim for himself, and eventually would be granted, the title “Father of Manitoba.” In fact, a good case can be made that Manitoba was the work of several fathers, including Macdonald and Cartier and, no less, a priest named Ritchot—all but one of the quartet being French.

When the Manitoba legislation came before the Commons, Sir Stafford Northcote, the governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, was watching from the galleries. In his diary, he commented on Macdonald’s speech: “He seemed feeble, and looked ill, but spoke with great skill. He makes no pretension to oratory, but is clear and dextrous in statement and gave very ingenious turns to his difficult points.” The most ingenious of the arguments Macdonald used to get the legislation approved was that the generous land grants for the Métis were the same as those offered to incoming Loyalists decades earlier. Such a reference, Northcote noted, “was of course most acceptable to the Ontario men.” The bill passed easily.

Northcote’s concern about Macdonald’s health was justified. Heavy drinking was only part of the problem.* For weeks now, Macdonald had felt intimations of some fundamental physical problem that periodically caused intense stabs of pain in his upper back and then vanished. On May 6, while he was in his office in the Parliament Buildings, a sudden pain burst through his entire body. He stood up to ease the pressure, lost his balance and fell full length on the carpet.

* By far the best study of attitudes in Quebec to the West in the late nineteenth century is the chapter “Confederation and the North-West” in A.I. Silver’s The French-Canadian Idea of Confederation, 1864–1900.

* Denison wrote a book, Cavalry Tactics, which won first prize in an international competition organized by the czar of Russia.

* Perceptively, Northcote spotted the particular way Macdonald performed when on a binge, recording that, although Macdonald continued to have official papers sent to him, “he is conscious of his inability to do any important business, and he does none.”