I do not know whether [Macdonald] is really an able man or not; that he is one of the duskiest horses that ever ran on any course is sure.

Lord de Grey to Lord Granville, 1871

For close to three months early in 1871, Macdonald engaged in what he called “the most difficult and disagreeable work that I have ever undertaken since I entered Public Life.” The reason for this uncharacteristic hint of self-pity was that he found himself ensnared in a contest with an opponent he admired immensely—Great Britain itself.

Otherwise, Macdonald’s circumstances could not have been more agreeable. He was in Washington, enjoying a mild winter. He was there as one of five members of a high-level British delegation at the most important conference between Britain and the United States since the Treaty of Ghent settled the War of 1812. He was lionized socially, invited to endless receptions and dinners by prominent hostesses. While protesting the burden of such engagements in letters home,* he no doubt found most pleasant the attentions of bare-shouldered Southern ladies.

At one reception, Macdonald met Ulysses S. Grant (his only encounter ever with a U.S. president). They discussed horses, or at least the excellent horses of someone they both knew—Nova Scotia’s lieutenant-governor, Sir Charles Hastings Doyle. At another reception, he met General William Tecumseh Sherman, whom he described as a “singularly agreeable person.” He enjoyed the Washington gossip, sending home amusing snippets, such as that senators and congressmen regularly had speeches printed in the congressional record which they had actually never given but had commissioned from “professional penny-a-liners.” On one occasion, two congressmen engaged the same hack, and two identical speeches were preserved for posterity even though neither man had spoken a word of them.

The Washington Conference was called to settle all the outstanding continental issues between Britain and the United States. The negotiations really began with meetings in the fall of 1869 between U.S. Secretary of State Hamilton Fish and the British ambassador, Sir Edward Thornton, to discuss the huge compensation demanded by the United States to settle the Alabama claims for the Union ships sunk by Confederate raiders that Britain had allowed to be built in its shipyards during the Civil War. Fish suggested that these claims could be dealt with simply by Canada being added to the Union. The dominion, he said, was “ripe for independence and the only class opposed to it were those connected with the government, the bankers and the smugglers.” In response, Thornton never disagreed that annexation might well be Canada’s future, although insisting that the choice was for Canadians themselves to make.

Macdonald knew about these talks, and he was also aware that many British officials and politicians thought the same way. Lord Monck, the former governor general, had sent him a note as he prepared to go to Washington, expressing the hope that Macdonald’s “experiment” in diplomacy would show him Canada was “nearly strong enough to walk alone.” As he didn’t know, Prime Minister Gladstone had already suggested to his cabinet that “we could sweeten the Alabama question for the United States by bringing in Canada.”

Macdonald’s position was all but impossible. He was but one member of the British delegation and had no official mandate to defend Canada’s interests. He was caught in a tug of diplomatic war in which the two players were the current global superpower and its impending successor. The team he was on had no choice but to make a deal—if necessary, at Canada’s expense. Yet he was bound, legally and morally, to make the best possible case for Britain’s interests rather than Canada’s. He could argue his cause only with his British colleagues, and only in private, so the Americans wouldn’t know that the delegation across the table was divided. Lastly, the four co-commissioners he would have to argue with were Britain’s best and brightest: a future chancellor of the Exchequer, a future viceroy of India, a future permanent head of the Foreign Office and a distinguished scholar of international law.* As well, keeping the minutes was Ambassador Thornton.

The Washington Conference was the most demanding exercise in realpolitik Macdonald ever undertook. He had no illusions about the magnitude of the task ahead of him; for close to three months, from February 26 to May 8, he never drank one drop too many. He and Lady Macdonald stayed at the Arlington Hotel, while the British team lived in a rented house, which, as Macdonald regretfully informed Charles Tupper, was bound to be “gay enough,” because the leader of the delegation, Lord de Grey and Ripon, to give him his full title, was “known to be hospitable and has brought his cook with him.”

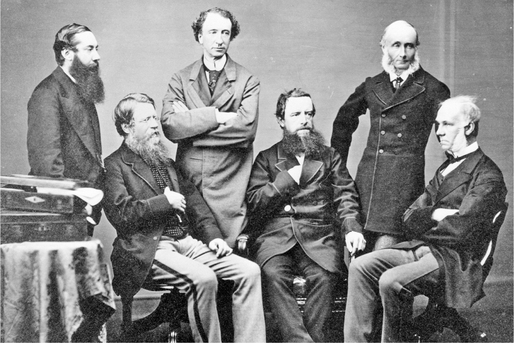

Five of Britain’s best and brightest, and one clever, guileful Canadian, gathered for the historic Washington Conference to settle all the outstanding quarrels between a declining superpower and a rising one. From the left: Lord Tenterden, Sir Stafford Northcote, Macdonald, Lord de Grey and Ripon and Sir Edward Thornton. (photo credit 12.1)

Macdonald had one key advantage over his grander colleagues: his negotiating experience was unmatched, if in national rather than international affairs, as in fact makes precious little difference. At home, he had frequently had to deal with heated disputes between mutually hostile provinces and between extremist Orange Protestants and ultramontane Catholics. As additional support, he brought with him to Washington Lady Macdonald (the other delegates were alone), two officials (the others had none) and some priceless advice from Sir Francis Hincks, his finance minister. A savvy old pro, Hincks told Macdonald that “the coming negotiation is really a game of brag, and by bragging high, you must win.” Victory, that is, would go to the one who claimed most convincingly to have been victorious. To this insight, Macdonald added a deft variation of his own: besides claiming a victory he might not really have achieved, he would also claim a defeat he had not really suffered—and secure compensation for it.*

In his annual message to Congress of December 5, 1870, President Grant set a record for being rude about his northern neighbour. He complained that Canada had been behaving like a “semi-independent but irresponsible agent” and accused the Canadian government of showing a lack of friendly feeling towards the United States. There was some truth to the latter complaint: the previous summer, a number of American vessels fishing in Canadian waters had been seized by Canadian patrol boats and their captains compelled to pay fines or have their nets and gear confiscated. The unfriendliness, however, had begun below the border. In 1866, the United States had decided not to renew its decade-long cross-border Reciprocity Treaty with Canada, chiefly as retribution for the widespread pro-Southern sympathy in the country during the Civil War. Canada took this decision hard. It was widely assumed that reciprocity was the reason for the country’s lively economic growth, although in fact a larger cause had been the demand for war materials. Macdonald, a free-trader by nature, had attempted to persuade Washington to open talks on a new treaty, but was told that Congress would never approve.

Washington, however, had overlooked the fact that the Reciprocity Treaty had secured for Americans two valuable advantages: free entry into Canada’s rich fishing grounds and free passage along the St. Lawrence River. As a result of Confederation, authority over these areas now resided with Canada, not Britain. Grant’s complaint that American fishing boats were being “seized without notice or warning, in violation of the custom previously prevailing,” was correct, but the action was completely legal.

Grant touched on another matter crucial to Canada in his speech. He declared ominously that the time was approaching when “the European political connection with this continent will cease,” but he also extended an open hand across the Atlantic. The United States, he said, was ready for a “full and friendly adjustment” of all the financial claims against Britain arising out of the Civil War and had an “earnest desire for a conclusion consistent with the honour and dignity of both nations.” These comments defined the agenda of the Washington Conference.

In the early 1870s, the world’s geopolitical order underwent a transformation comparable to the end of the Cold War in the 1980s. In Europe the radical event was France’s crushing defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 and the addition to the map of a united Germany. Simultaneously, Russia showed it had fully recovered from defeat in the Crimean War by declaring that it no longer accepted demilitarization of the Black Sea. Henceforth, Britain had to concentrate its diplomatic skills and military capability on Continental Europe. The last thing it needed was a conflict in North America precipitated by some friction along the Canada-U.S. border. As the august Times of London put it, crossly but perceptively, “the mother country has become the dependency of the colonies.” In this new situation, Canada was in no way automatically expendable; honour and prestige mattered to Britain, as did the integrity of the Empire. But it did make Canada a useful pawn to be moved about the board—and even, if circumstances required, off it.

There was, however, one countervailing factor that Macdonald was not yet aware of: the British were in the process of reinventing their Empire. Created originally by naval power at the service of trade, the Empire was now turning into a source of glory and pride for its own sake. Britain had been divided between “Little Englanders,” who saw no value in the colonies, and “Big Englanders,” who hungered for fame and fortune. The latter group was winning now, one telling signal being the runaway success in 1869 of Charles Dilke’s book Greater Britain, a paean to imperialism.* The real change lay just ahead, when Disraeli, in a famous speech at the Crystal Palace in 1872, embraced the newly enfranchised urban workers as allies, on the grounds that they, like him, believed in “maintaining the greatness of the kingdom and the empire” (as they did, if only for the sake of some colour in their hard lives). There were even signs that Gladstone’s new Liberal government was beginning to distance itself from its anti-colony past. All these trends would give Macdonald some unanticipated leverage in Washington.

The tap on Macdonald’s shoulder came in February 1870, after Washington and London had agreed to set up a Joint High Commission to negotiate all outstanding issues between them and, by extension, those affecting Britain’s dependency, Canada. Macdonald was London’s second choice, after the well-connected John Rose—a friend of Prince Edward (later Edward VII) and Hamilton Fish as well as Macdonald. But Rose was married to an American and now lived permanently in England, and so could not represent Canada. Macdonald’s first reaction to the invitation was to say no; Canada’s influence would be slight and, as part of the British team, he would lose any right to criticize decisions reached by the two giants. However, as he told Governor General Lisgar, without any Canadian voice in the room the outcome might be “a sacrifice of the rights of the Dominion.” So he accepted his role as a joint high commissioner, or, as they called each other, a “High Joint.” He admitted to Rose: “I contemplate my visit to Washington with a good deal of anxiety. If things go well, my share in the Kudos will be but small, and if anything goes wrong, I will be made the scapegoat.”

The trouble began at Macdonald’s first meeting with the head of the delegation, Earl de Grey and Ripon, who came to see Macdonald at the Arlington Hotel to report on a conversation he had with “a leading [American] statesman”—Fish, undoubtedly—who told him, “The United States must have the inshore [Canadian] fisheries, but were ready to pay for them.” Macdonald replied that Canada would accept only reciprocity or major tariff concessions for its fisheries, but not cash. Moreover, he warned that Britain “had no right to injure posterity by depriving Canada … of her fisheries.” De Grey responded that his informant had made it clear that Congress would never accept reciprocity. Macdonald retorted that Canada’s fisheries were far superior to those of the United States and that Canada might well surpass its neighbour as a maritime power. This first encounter confirmed for the duration of the conference de Grey’s pre-meeting assessment of Macdonald—that he expected to have “a great deal of difficulty in bringing him to accept moderate terms.”

In addition, an issue that interested only Canada—its fisheries—had emerged as a potential deal-breaker for the entire conference. To the surprise and then the dismay of both the British and the Americans, Macdonald wouldn’t shut up about them. Day by day, it became apparent that a conference staged so that two of the world’s most powerful nations could settle all their outstanding differences was being hijacked by a third-order interest of a second-rank power. As was almost surreal, Canadian concerns went on to occupy close to two-thirds of the time the delegates spent around the table. An American miscalculation contributed to this outcome: its delegation had insisted that the Canadian fisheries be the first item on the agenda, taking for granted that the matter would be disposed of easily.

In fact, Macdonald almost certainly knew full well he was exaggerating the importance to Canada of its fisheries; Hincks had told him they were “a mere expense.” And since he knew that reciprocity was unattainable, he was bluffing when he insisted Canada could accept only reciprocity as payment for American access to its fishing grounds. Indeed, a year earlier he had told an American, George W. Brega, that cross-border free trade “could only be effected by the pressure of American interests upon Congress.” Here, to an uncanny degree, Macdonald was anticipating the Washington lobbying strategy Canada would adopt more than a century later.* At the time, he simply refused to accept that Canadian concerns merited any less attention than those of Britain and the United States. Most directly, Macdonald needed no instruction about the political importance of the fisheries, given the disproportionate number of ridings in the Maritimes.

During the conference, Macdonald’s great handicap was that he was the lone Canadian voice. So he invented a second voice in support of his positions. He did so by writing regularly to his cabinet members back in Ottawa (where Cartier was acting prime minister) and asking their opinions about the issues of the day. The ministers understood that he wanted replies that could be shown to the other British delegates, in particular that they should instruct him to hold firm on key issues. Macdonald could then tell his British colleagues he had no choice but to follow the directions given him by his government. On one occasion, de Grey solicited support from his superior, Foreign Secretary Lord Granville, for his insistence that Macdonald’s stand on Canada’s fisheries not be allowed to bring the entire conference to a halt. Macdonald concocted a directive from his cabinet that instructed him to write to Colonial Secretary Lord Kimberley, asking whether Canada had the right to make decisions about its own fisheries. Kimberley, unaware he was being lured into a trap, answered forthrightly, “His Majesty’s Government never had any intention of disposing of the fisheries of Canada without her consent.”*

Macdonald called this response, which directly contradicted the parallel exchange between de Grey and Granville, a “floorer”; he then set out to use it to gain for himself what amounted to a veto over the entire conference. He was able to do so because Britain and the United States had agreed to “bundle” all the outstanding issues together, so their alternatives were either to agree on everything or on nothing. The British team, recognizing that the saltwater fisheries belonged to Canada no differently from the way the inland, freshwater ones did, accepted defeat. On March 20, Granville instructed de Grey that any deal reached on the fishery “must be subject to ratification by the Canadian Parliament.” A mere colony had won a veto over the outcome of a bilateral conference involving two of the world’s most powerful nations. But this de facto veto was sharply double-edged. Should Macdonald actually shut down the conference for the sake of better terms for the fishery, he and Canada would pay a fearful price: unflagging hostility from both Britain and the United States. The pair would promptly have staged a second conference with no Canadian present.

From this point on, the Washington Conference became two conferences. The first involved the British-American negotiations; here, the parties reached important decisions with commendable speed, such as that international arbitrators should determine the scale of British reparations and, in return, that the United States would accept an expression of regret in place of an apology from Britain. The second conference pitched Macdonald against all the other delegates, though mostly it involved only Macdonald and de Grey.

Initially, Macdonald’s opinion of de Grey was positive. He wrote to Lisgar, “He is quick in perception, cool in judgment, of imperturbable temper … [and] much liked as being frank and cordial.” Indeed, de Grey was widely regarded as capable and decent. Although to the manor born, he had become a Christian Socialist. Later, as grand master of the Freemasons of England, he caused a sensation by converting to Roman Catholicism. After Washington, he won the ultimate Imperial prize as viceroy of India.* The difficulties between him and Macdonald were essentially that de Grey was seeking peace with the United States, while Macdonald was seeking victory over it.

Governor General Lord Lisgar, who broke all the rules of diplomatic and gentlemanly conduct by leaking to British delegates at the Washington Conference the contents of Macdonald’s private letters to his cabinet in Ottawa. (photo credit 12.2)

Macdonald’s obduracy led de Grey on one occasion to step out of character—he resorted to a bribe. During a conversation with Macdonald, as de Grey later recalled, “the words ‘Privy Councillor’ somehow escaped my lips.” If Macdonald would stop ranting about the fishery, intimated de Grey, he could gain the honour of becoming the first colonial admitted to the Privy Council of Britain. The bribe worked—but only halfway. A year later, Macdonald made sure that the departing governor general, Lord Lisgar, passed on to his successor, Lord Dufferin, full information about the matter. At the conference, though, he continued on about the fishery.

On April 15, de Grey wrote to Lord Granville to let him know that, while Macdonald “professes to be unable to take a step without his colleagues in Ottawa, we learn from Ottawa that he has things in his own hands and has full discretion to act.” Macdonald’s ruse had been found out. The manner of the discovery was unfair and, more shocking yet, ungentlemanly. It turned out that Governor General Lisgar had been secretly sending to the British delegates copies of all Macdonald’s letters to the cabinet and their replies—correspondence that had been sent to him because they concerned decisions being made by “his” ministers. Macdonald’s co-commissioners now read what he really thought of them, such as that they were easily “squeezable” by the Americans and that “they seem to have only one thing on their minds, that is to go home to England with a Treaty in their pockets settling everything no matter at what cost to Canada.” Lisgar, in his covering letter to de Grey, described Macdonald as “a huckster” who had “scarcely a shadow of consideration for imperial interests.” Granville, more experienced in international affairs, appreciated that Macdonald was just doing what his job as prime minister required. He wrote to Gladstone that “Sir John A. Macdonald seems to have more to say for himself than his brother Commissioners admit.” Even Gladstone agreed that Britain should not “be hustled about” by the United States on the fisheries.

Macdonald negotiated a compromise with de Grey: he agreed that the Americans could enter Canada’s fishing grounds in return for a cash payment, but the term would last for only ten years. The amount of the payment would be decided through arbitration by an international panel. Here, Macdonald was overplaying his hand, and Fish, who at one time had suggested duty-free entry for coal, salt and lumber, withdrew the offer on the grounds that the Senate would never agree to it.

In fact, the fisheries were but a sideshow for Macdonald. The issue that really mattered to him was compensation from the United States for the Fenian raids. Although they had been defeated without great difficulty, these cross-border raids had inflicted a heavy cost in blood and property damage, and Canadians’ feelings about them were similar to those of Americans about the Alabama claims. Compensation for the Fenian raids was the principal reason Macdonald had agreed to come to Washington.

But the issue of American compensation for these raids was not even on the agenda. Either by incompetence or by calculation, the British had neglected to put the item on the list. They guessed, no doubt correctly, that the Grant administration would never accept losing face by admitting that its predecessors—Lincoln above all—had been at fault.

When de Grey finally told Macdonald there would be no American compensation for the Fenian damages, Macdonald realized that the country he loved had all along planned to use Canada as a sacrificial lamb, securing better terms on the Alabama claims by putting no pressure on the Americans to compensate Canada for the damages done by the Fenians. Still, continued de Grey, Canada could walk away with a reasonably full pocket. De Grey had done this by coming over to the Arlington hotel after church on Sunday, April 16, to tell Macdonald, as he later reported to Cartier in a confidential letter, “he was in a position to inform me, in strictest confidence … that Her Majesty’s Government would, if all other matters were settled and it were not to be considered as a precedent, consent to pay Canada a sum of money [for Fenian damages] if the United States refused to do so.” So the lamb was at least to be reasonably well fed.

De Grey’s objective was comparatively straightforward: now that all the British-American issues had been resolved, he wanted to get a treaty signed and then ratified by the three legislatures—in Westminster, Washington and Ottawa. He needed Macdonald to pledge publicly to use his immense influence to ensure that the Parliament in Ottawa actually passed the treaty. Macdonald’s aims were more complex: he still wanted a better deal for Canada’s fisheries; even more, he wanted the British government to declare publicly that it would compensate Canada for the Fenian raids.

So began an elaborate and a prolonged diplomatic dance. Macdonald fired off a letter to de Grey declaring it was his strong conviction that the fisheries terms “will not be accepted by Canada” and that he would find them difficult to justify or defend in the Canadian Parliament. The British delegates “all made speeches” at him in response, but he didn’t back down. The heat increased during the first two weeks in April, until de Grey told Macdonald sternly that “a failure in the settlement of the Fishery question would involve a complete disruption of the negotiations.” There were many in England, he warned, who would rejoice were Canada to confirm that “the Colonies were a danger and a burden.” In return, Macdonald told de Grey that he was considering absenting himself from the conference, thereby letting the Americans know he doubted that the Canadian Parliament would sanction the treaty. De Grey retorted that he found such words “a grave statement to make.” Two days later, Macdonald wrote to a Montreal friend that events over the next few days might be the “entering wedge” of a severance between Canada and Britain.

Having gone to the brink, Macdonald now took a step back. He downplayed his concerns about the fishery, asked that his reservations about the deal be “unmistakably and publicly affirmed” and agreed to present all the other aspects of the treaty to Parliament. Tempers began to cool—somewhat. As the conference neared its end, Macdonald wrote to de Grey emphasizing “the expediency of the Fenian matter being taken up without delay and settled by H.M. Government.” In his last letter to Macdonald in Washington, however, de Grey cautioned, “You would incur a responsibility of the gravest kind if you were to withhold your signature.”

De Grey had, in fact, made only a private verbal promise to Macdonald to compensate Canada for its Fenian losses. Late in July, two months after the conference ended, Macdonald felt sufficiently troubled by this to write to Lisgar: “I cannot for a moment suppose the British Government will hesitate to carry out the assurance given to me by Lord de Grey at Washington.” He did not know that, at the end of the conference, de Grey had written to Lord Granville to say: “If he [Macdonald] gets the consent of the Canadian Parliament to the stipulations of the Treaty for which it is required, he will deserve reward, but if he does not, he ought to get nothing.”

The Washington Conference ended on May 8, 1871. Both sides gave the other lavish dinners, and the Freemason lodges in Washington entertained the two British delegates who were members.

On the key issue of the Alabama claims, Britain and the United States agreed to set up a five-member international arbitration panel to determine the amount of the payments.* Britain made no apology for the Alabama affair, but did express regrets. The Canada-U.S. fishery dispute was settled when the Americans agreed to pay for entry for a ten-year term, with a three-member international panel to decide the amount of the payment. (The panel’s decision, made public in 1877, gave Canada a totally unexpected award of $5.5 million. The United States was so annoyed by this settlement that it cancelled the deal when it expired in 1878.)

The conference’s great achievement was to end the long history of hostilities between Britain and the United States in North America, to establish normal relations and, once time passed, to make it possible for a special relationship to develop between them. Canada gained the fisheries deal, the potential of British compensation for its Fenian losses and, because of the veto it possessed in the form of its Parliament’s right to ratify the treaty, implicit U.S. acceptance of Canada’s autonomous existence. The American annexationist movement faded away, although the “ripe fruit” doctrine would linger for decades, and the power and allure of America would always affect the course of Canadian national development. But the decision on the existential choice in Canadian life—whether to continue as Canadians or to become Americans—would be made henceforth by Canadians, not by Americans.

Before leaving Washington, Macdonald stepped back to give himself a wider view. He understood the scale of the achievement: “It seems to me that if all the rest of the World were at War, Great Britain and the United States ought to be friends,” he wrote in one letter home. As for Canada, “With a Treaty therefore once made, Canada has the game in her own hands. All fear of war will have been averted.” In another letter, he added the cautionary note “I am no believer in eternal friendships between Nations.”

After the delegates returned home, only two matters remained to be resolved: Britain’s promise to pay Canada compensation for the damages caused by the Fenian raids, and Macdonald’s promise to persuade the Canadian Parliament to ratify the treaty. The diplomatic dance between de Grey and Macdonald continued, and neither issue would be settled until early in 1872.

Macdonald had set the tone for the continuing dispute when he signed the treaty in Washington. He walked over to the table, picked up the pen and said to Fish, who was standing nearby, “Well, here go the fisheries.”

This comment was a gross and deliberate exaggeration. In fact, the Halifax Times’ judgment on the new fisheries arrangements was, “We have fished for twelve years alongside the United States, and were not ruined.” The Globe, predictably, did fulminate that Macdonald had shown himself to be “but a poor parody of a statesman” who had “giv[en] away Canada’s fisheries … asking nothing in return,” and who, by failing to secure any compensation for the Fenian raids, of which no announcement had been made, had left Canadians “insulted, injured and outraged.”

In fact, that was exactly the response Macdonald wanted. The Globe, and George Brown, knew nothing about de Grey’s offer of compensation provided that Macdonald navigated the treaty through Parliament. The criticism of the fisheries deal, which Macdonald straight-facedly described to de Grey as a “universal storm,” simply strengthened his hand in negotiating the Fenian payment. As for getting Parliament’s approval, Macdonald calculated that the best way to do it was by doing nothing. He instructed Conservative newspapers to make no comment at all about the treaty, pro or con. He himself remained silent on the issue, initially to Brown’s surprise, though the publisher gradually began to suspect that Macdonald was up to something.

No one was more unsettled by all of this than de Grey. He told his minister, Lord Granville, “I do not know whether he is really an able man or not; that he is one of the duskiest horses that ever ran on any course is sure, and that he has been playing his own game all along with unswerving steadiness, is plain enough.”

While tacking back and forth, Macdonald knew exactly where he had to go. He wanted to get the promise of compensation for the Fenian raids made public and use it to secure Parliament’s approval for the treaty, including the fisheries arrangements. He didn’t know, though, that there was a large obstacle in his way. One of the letters he had written from Washington to his ministers in Ottawa, which Lisgar had passed on to the British delegation, contained the damning passage “Our true policy is to hold out to England that we will not ratify the treaty … [so that] we can induce to a liberal offer.”

This sentence soon provoked righteous fury in London. “Knavery is not too-harsh a word,” said Colonial Secretary Kimberley. Gladstone was as angry: “I hope the ‘liberal’ offer which Sir John Macdonald intends to conjure from us will be nil.” That is, no parliamentary approval, no payment.

At one time, Macdonald came close to a public breach. He warned Lisgar that, if Britain made the payment conditional on earlier parliamentary approval, “I should consider [this] a breach of the understanding and would at once abandon any attempt to reconcile my colleagues or the people of Canada” to the treaty.

Luck intervened. In the summer of 1871, British Columbia entered Confederation. To get it aboard, the government had to promise not just a transcontinental railway, but an immediate start to it and its completion in just ten years. Macdonald now had an inspired idea (or had it suggested to him): rather than a cash payment for the Fenian damages, London should agree to guarantee a loan—a commitment far easier to get through the Westminster Parliament. Kimberley wrote to Gladstone that the British government should not “make the assent of the Canadian Parliament to the Treaty a condition of our payment.” The prime minister agreed, and so advised Queen Victoria. On January 22, 1872, Macdonald informed the governor general that the treaty would be placed before Parliament at its coming session and that assent was assured because Britain would announce in advance its intention to guarantee a £2.5 million loan to be spent by Canada on railways and canals.

Macdonald had played a trump card in his latest tournament of “the long game.” Right afterwards, he had to pick up another weak hand. An election could not be delayed for long, the last one having been held in the fall of 1867, now close to the five-year statutory limit. The omens could not have been darker. The Conservatives had just lost Ontario—the country’s richest and most populous province.

* The period of the Washington Conference, early March to early May 1871, is the most extensively recorded of all in Macdonald’s life. He wrote many letters to Cartier, Tupper, Rose, Lisgar and many others, simply because he was away from his home town.

* Montague Bernard, from Oxford University, was a distant relative of Agnes Macdonald.

* Despite the importance of the Washington Conference to Canada—the peaceful settlement of North America into its present form, and Canada’s first appearance on the international stage—the only in-depth study by a Canadian historian is in the second volume of Donald Creighton’s biography of Macdonald. In contrast, American historians have written two books and numerous articles on the subject, one of which describes Macdonald as “considered by some the ablest statesman of the era.”

* Exceptionally talented, Dilke seemed headed for the prime ministership before he was brought down by an epic sex scandal involving a mistress and her maid—perhaps even all having been in the same bed at the same time.

* That strategy, initiated by Ambassador Allan Gotlieb in the 1980s, involved lobbying Congress on issues that concerned Canada, such as reducing acid rain, by persuading Americans sympathetic to the cause to head up the lobbying effort. Macdonald even anticipated future Canadian tactics by hiring Brega to lobby for free trade with Canada, if unsuccessfully.

* The exclusively Canadian grounds extended only to the three-mile limit, and there was the usual haggling over whether these encompassed all the sea within bays whose headlands were far apart.

* While viceroy, de Grey won a war in Afghanistan.

* Each side was to appoint one member of the arbitration panel, while the emperor of Brazil, the king of Italy and the president of Switzerland would each appoint their choices.