The advent of the Grits to power just now would shake Confederation to its very centre.

Macdonald to Archbishop Thomas Connolly of Halifax

The election of 1872 worried Macdonald more than any he had waged since he’d first made it to the top as premier back in 1857. He showed his uneasiness by delaying the election to the very end of the five-year limit—and, even more sharply, by his manner of drinking. Instead of just binging, he was now quaffing it down consistently and heavily. Alexander Campbell, his former law partner and now a minister close to him, reported later that, during the actual election campaign, Macdonald “from the time he left Kingston after his own election … kept himself more or less under the influence of wine … and really has no clear recollection of what he did on many occasions.”

Secondary factors would have heightened his sense of anxiety. The gallstone attack a year earlier had given Macdonald clear intimations of his mortality. He had survived the crisis, but also acquired a new fragility. In June 1872, in a letter to Rose, he admitted: “I only wish that I was physically a little stronger. However, I think I will not break down in the Contest.” His home life had changed profoundly. Each time he returned home from the office he went straight over to his daughter, Mary, now three, picked her up, wrapped himself around her, told her tales and made her laugh. But Mary’s shrunken form and oversized head could not but signal that he had entered some kind of a hospital. As well, the early ease and intimacy between himself and Agnes had passed. One reason Macdonald spent such long hours in his office was that he could escape there from his sombre home into the rough and genial male company of the political arena; Parliament Hill served him as a sort of second home.

Mary Macdonald at the age of three. All hope of recovery was now gone: she could not feed herself, clothe herself, turn over in bed or stand. Visitors unaware of her condition would watch astonished as the prime minister massaged her shrunken limbs to try to cause the blood to circulate. (photo credit 14.1)

His actual political concerns were sizeable. As he wrote Archbishop Thomas Connolly of Halifax, “The advent of the Grits to power just now would shake Confederation to its very centre, and perhaps break it up.” This analysis of the state of the nation was transparently self-serving. But from Macdonald’s perspective, what was at risk was a critical and exceptionally difficult phase of nation-building, one that could make the nation or break it.

He had, in his first term, achieved the goal of stretching the nation from sea to sea so that, at least on maps, it now looked to be as substantial as the United States. Most of this impression was little more than a dream, and a good deal of bluff: in practical terms, British Columbia, the newest addition, was as distant from Canada “as Australia,” as Macdonald himself had said; and the North-West was peopled by Aboriginals and Métis, but scarcely any settlers. Canada was really no more than “a geographical expression.” To become an actual country, it had to have a spine—a railway that could bind Canadians together and attract immigrants to start filling up the vast empty spaces. Yet, in Parliament’s last session before the election, all that Macdonald had been able to do was pass legislation setting up the shell of a transnational railway company.

What Canada needed, Macdonald was convinced, was time. The Liberals had said nothing good about bringing British Columbia into Confederation or about his attempts to create a railway company to build a backbone of steel across the country. In no way did they wish to harm the nation, but their vision was modest. Blake viewed Confederation as a “compact” among the provinces rather than as a whole larger than its parts—that absurdly ambitious vision that Macdonald had in mind.

Time was the magic ingredient. The country needed it; Macdonald needed it; and the country needed him—his love of power justifying that last logical jump. Macdonald expressed this view most explicitly in another letter to Rose, on March 5, 1872: “I am, as you may fancy, exceedingly desirous of carrying the election again; not with any personal object, because I am weary of the whole thing, but Confederation is only yet in the gristle, and it will require five years more before it hardens into bone.”

“Gristle into bone” became his war cry. In fact, gristle (cartilage) cannot harden into bone, the two being quite different substances. Macdonald knew that perfectly well, but it was an effective metaphor. Over time, he would alter the amount of time needed—a decade, a quarter-century, once as long as a century—before Canada could mature into a real nation rather than remaining “a prospective nation,” as one Canada First nationalist put it. And over time, this would be exactly what happened. Macdonald’s particular contribution was to win for Canadians the time for their country to mature into a second, distinctive North American nation.

First, however, he had to win the election.

No Canadian politician, either afterwards or before, has ever done better in elections than Macdonald. From Confederation on, he would compete in seven and win six. The core reason was simple: most people liked him a lot, both for himself and in comparison with anyone else available.

Ordinary people outright loved him, because he was funny, unstuffy, a natural showman, daring, treated all as equals and was adept at putting down hecklers in a way that never humiliated them. The irony here is that Macdonald always opposed widening the franchise, even though the poor and landless were his most ardent supporters, as were women, those others not welcomed at the ballot boxes. He never patronized his audiences; rather, he paid them the supreme compliment of never talking at them from a prepared text but rather talked with them, ad libbing his actual speech and coming out with his best lines whenever heckled or interrupted. Later, Wilfrid Laurier would be famous for the vote-winning attractiveness of his “sunny ways”; but Macdonald was the first of that seductive political breed in Canada.

Macdonald’s other great asset was that he was ferociously competitive. Winning was everything to him. Whenever an election approached, he dropped everything and applied all his inventiveness and capacity for hard work to the challenge.

This time, one of his initiatives was to create a Conservative newspaper, the Toronto Mail, to rival the Liberals’ Toronto Globe. He began a campaign to raise the needed funds, contributing ten thousand dollars himself, and persuaded an experienced journalist, T.C. Patteson, to become the editor, guaranteeing him a government sinecure if the venture failed. When he saw the first dummy edition, he worried its tone might be considered offensive: “You call G.B. [George Brown] a bully and a tyrant,” he wrote to Patteson. “He is both, but is it wise to throw down the gauntlet so early and so offensively?” Soon his competitiveness took over: “The first number is a good one—for a first number,” he wrote. “You must assume an appearance of dignity at the outset. The sooner, however, that you put on the war paint and commence to scalp the better.”

One campaign idea he toyed with was for the Conservative Party to change its name to something more compelling, such as the Union Party, the Canadian Constitutional Party or the Constitutional Union Party. These titles, he argued, would signal that the party stood for “union with England against all Annexationists and Independents, and for British North America … against all anti-Confederates.” The idea died, as did Macdonald’s later suggestion that the party should be called an “Association of Union and Progress”—whatever that meant.

His electoral tricks were endless. He informed one candidate: “You will be surprised to receive an appointment as an Issuer of Marriage Licences.” The candidate, who was an Ontario provincial member, was to accept the honour, “& then in a day or so you must write a letter of resignation.” Macdonald had figured out that this individual could qualify himself to become a federal candidate simply by taking on a provincial post that, by law, required him to resign his legislature seat. He warned candidates against being too generous too early: “If you give a man five dollars before the nomination, he will have spent it and want another five dollars before polling.”

As always, religion trumped everything else. Macdonald urged the bishop of Hamilton to “put the Episcopal screw” onto Kenny Fitzpatrick, whom Macdonald wanted as a Catholic candidate but who kept protesting he was not sufficiently educated to be an MP; Macdonald explained that Canada’s Parliament was fast becoming one where “only the leaders speak and the majority are satisfied with … giving silent votes with their party.”

In one small way, the election of 1872 made Canadian political history. For the first time, a working-class candidate, H.B. Witton from Hamilton, was elected to Parliament—and as a Conservative. The person who made Witton’s victory possible, and the source of Macdonald’s great piece of electoral luck, was none other than George Brown.

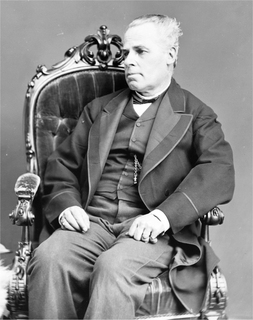

George Brown, owner of The Globe, moral and intellectual leader of the Liberals even though no longer in Parliament, was by far Macdonald’s ablest opponent. Despite his abilities, Brown lost almost every contest. (photo credit 14.2)

While Canada was still overwhelmingly rural, an urban proletariat was beginning to emerge in Montreal, Toronto and Hamilton, where industrial workers now made up close to one-fifth of the labour force. Canadian workers put in longer hours for less pay than their British and American equivalents, and their unions were weak or non-existent.

The idea of union activism was beginning to spread to Canada from Britain and the U.S., though. In 1871 the Toronto Trades Assembly was formed as a voice for the many union locals in the city. Its leaders seized on the idea of launching a Nine-Hour Movement, already victorious in Britain.* On February 28, 1872, Typographical Union No. 19 informed printing firms in Toronto that its members wished to work nine hours a day instead of ten. The night compositors, the most skilled workers, met with Brown, the Globe‘s proprietor, and he agreed to shorter hours and a pay raise. But when the less-skilled printers sought a similar agreement, Brown refused to meet with them. On March 25, every Typographical Union worker left his bench. Brown instantly formed an employers’ consortium of various kinds of businesses that agreed to help the Globe resist “any attempt on the part of our Employees to dictate to us by what rules we shall govern our business.”

The workers had their own countermeasures prepared. A newspaper called the Ontario Workman appeared on the streets to denounce oppression by the capitalists, and a succession of mass protest meetings organized by the Trades Assembly raised funds.† A pro-Conservative newspaper, The Leader, took the side of the strikers, giving them a public platform. Most adroitly, the strikers urged British workers to warn “mechanics” or skilled workers planning to emigrate that they would be coming to a land where the working man had no rights. The demonstrations escalated, and one rally brought out ten thousand men, women and children. Brown, though, had the law on his side. He had warrants issued against members of the Typographical Union’s Vigilance Committee, and on April 16 thirteen were arrested on charges of conspiracy.

At this point, Macdonald rose in the House of Commons to announce that legislation would be introduced “to relieve Trade Unions from certain disabilities under which they labour.” The bill, he said, would place them on equal footing with unions in England. Brown’s arrest warrants were valid because, under existing Canadian law, unions had no right to organize. In Britain, trade unions had this right under a law enacted by Gladstone’s Liberal government. Canadian Liberals could hardly criticize British Liberals, so Macdonald’s bill passed with scarcely a dissenting word. The case against the leaders of the Typographical Union was dropped abruptly. In the Globe, Brown declared that Macdonald’s only motive had been to gain “a little cheap political capital.”

Brown’s attempt to use the law to crush a strike by Globe typographers prompted Macdonald to pass legislation to legalize trade unions. In one inadequate response, the Globe appealed: “Our advertising friends will oblige us by aiding us in this matter.” (photo credit 14.3)

That was precisely Macdonald’s objective. Union leaders now appeared on platforms with Conservative candidates. The Toronto Trades Assembly staged a huge rally to express its gratitude, presenting a jewelled case to Lady Macdonald and providing Macdonald with an opportunity to charm the crowd by saying that, as a maker of cabinets, he was himself an industrial worker.

A bit more than electoral opportunism was involved. Macdonald was also worried that harsh labour laws in Canada would discourage immigration from Britain.* With his railway plans progressing, immigration had become a key nation-building policy. Earlier in the parliamentary session, he had enacted a Dominion Lands Act, which made a 160-acre lot, or quarter-section, available to settlers for a nominal ten-dollar fee. Two years earlier, he had initiated a comprehensive survey of the North-West to map these sections—one of the great administrative accomplishments of nineteenth-century Canada.

In due course, Witton was elected as a working-class, Macdonald Conservative, but thereafter he did precious little to advance labour’s cause. “We had met him soon after the election when he dined in a rough suit,” Lady Dufferin, the wife of the incoming governor general, recorded in her diary, “but he now wears evening clothes.”†

Nevertheless, by scoring off Brown and by shaking the hands of industrial workers, Macdonald had gained momentum. He used it now to overcome other obstacles in his path.

The most troubling matter Macdonald had to settle before going to the polls was the demand for an amnesty for “misdeeds”—in Bishop Taché’s delicate phrase—committed during the Red River Resistance. Early in 1872, Father Ritchot dispatched a petition to the governor general urging him to “proclaim the amnesty which was promised us when negotiating in Ottawa.” Macdonald advised Governor General Lisgar that “no answer should be sent,” and Lisgar in turn informed London that he had never made “an assurance or promise of an amnesty.”

Taché made yet another attempt to secure an amnesty. He went to Ottawa and met with Macdonald, who told him forthrightly that “no government could stand that would endeavour to procure the amnesty.” At this meeting, Macdonald came up with the idea of sending money to Riel, through Taché, to enable him to survive in the United States. That solution put the amnesty issue to rest—for a while. In the election campaign, whenever hecklers demanded to know when Riel would be brought to justice, Macdonald would reply solemnly, “Where is Riel? God knows. I wish I could lay my hands on him.”

A $5,000 reward issued by the Ontario Liberal government for Riel’s arrest made it risky for him to come back across the border. He did it repeatedly: once, after winning a seat in Manitoba, he slipped into the Parliament Building to sign the register as an elected MP. (photo credit 14.4)

The easiest of the outstanding issues requiring attention was the Washington Treaty. By delaying dealing with it for so long, Macdonald had allowed everyone’s temper to cool. Not until May 3, 1872, did he bring it before Parliament. By then, he had received a copy of a message sent by the colonial secretary to Lisgar pledging that, once the treaty was passed, the British government would guarantee a £2.5 million loan for the railway.

Macdonald’s speech was long—four hours—and one of his best. He recalled that he had been reluctant to become one of the commissioners, and had done so only to protect Canada’s interests. Once in Washington, he had been forced to compromise so that Britain and the United States could make peace. Although he was unhappy about the fisheries settlement, it was at least now firmly established that Britain could not cede those fisheries without Canada’s consent. He ended by asking MPs “to accept this treaty, to accept it with all its imperfections, to accept it for the sake of peace, and for the sake of the great Empire of which we form part.” The debate was brief, and the treaty was ratified by a margin of two to one.

The last issue to be dealt with was the most important of all—the identity of the company that would build the railway. The enabling legislation had already been brought before the House and passed after a desultory debate. The government would review bids to build the line, and the winning company would receive thirty million dollars in cash and fifty million acres of prairie land in alternate blocks on either side of the line. Two important matters were left unsettled. One was how the government would respond to a new demand by British Columbia that the railway should extend to Vancouver Island by way of a succession of bridges across the island-dotted part of the Georgia Strait opposite Campbell River. (This would have required building no fewer than seven bridges spanning the deep, tide-ripped waters). The other matter was a good deal more consequential: how the government would decide who should actually build and run the railway. As the Commercial & Financial Chronicle noted shrewdly, the bill allowed the government “to make almost any agreement it chose.”

At this time, Macdonald was still trying to get David Macpherson to combine his Inter-Oceanic Railway with Hugh Allan’s Canadian Pacific, but Macpherson was refusing to accept that Allan be named president of the company. He brushed aside Macdonald’s compromise suggestion that, while Allan would have the top job, each could nominate the same number of members to the board.

Macpherson’s suspicions were wholly justified. Despite Allan’s promise to Macdonald, he was continuing his secret partnership with the Americans. He even convinced himself he was doing so for the country’s sake, telling the Northern Pacific president, George Cass, he was “really doing a most patriotic act.” While lying to Macdonald, Allan lied as amply to his American colleagues: he told them that, because Parliament could not approve legislation that put Americans in charge of a vital national project, all the stock of the Canadian Pacific would have to be held in the names of Canadians. American investors should place a certificate equal to one million dollars in gold in his own Merchants’ Bank and, once the government awarded the contract, this money would be used by the Americans to buy shares from the Canadians who held them.*

All these intrigues were still a secret, though suspicions about Allan’s dealings were beginning to leak out. As for Macdonald, he was delighted with what had been accomplished during the parliamentary session. He told a friend that he and the Conservatives had “routed the Grits horse, foot and Artillery.” He now called the election.

Macdonald set off immediately to campaign in western Ontario, hastily doubling back to Kingston when he heard that the contest in his own riding was close. He worked very hard in Ontario, spending two full months travelling, speaking, organizing local election campaigns and pushing back against the interventions of the new provincial Liberal government, which deployed all its patronage and influence to defeat the Conservatives. As he later told a supporter, “Had I not taken regularly to the stump, a thing that I have never done before, we should have been completely routed.”

It was just enough. In his own riding, he won by only 130 votes. The Canadian Parliamentary Guide records the overall result as 104 seats for Macdonald and 96 for the opposition parties, leaving him with a bare majority of 8. In Nova Scotia, however, where the Guide gave Macdonald only 10 seats, most of the MPs, now that “better terms” had been gained, in fact consistently supported him. Macdonald’s effective majority thus was nearer to 30. In the two new provinces, British Columbia and Manitoba, he won all of their 10 seats, a number far larger than their populations warranted.

He had, though, suffered one incalculable loss. Cartier, his partner for so many years, had been defeated in his own Montreal East riding. The person responsible was Hugh Allan.

For months now, both before and during the election, Allan had also been lying to Cartier, the man who had done much to guarantee him the presidency of the Canadian Pacific. Allan knew very little about politics, and he almost never bothered to vote. But he knew a great deal about power. He came to the conclusion that, to make certain his Canadian-American syndicate would gain the CPR contract, it was necessary for Cartier to be reduced to a powerless tool. Cartier at this time wielded immense influence, because he and Macdonald were close and, as the necessary foundation for their intimate alliance, because he controlled forty-five bleu MPs, who, as Allan noted, “voted in a solid phalanx for all his measures.” If a significant number of these men ever wandered, their absence could “put the Government out of office.” That would put the government at Allan’s mercy.

Allan went after Cartier with chilling skill. He knew that Quebecers had long wanted a railway from Montreal to Ottawa through the country north of the Ottawa River, but that Cartier, as solicitor of the rival Grand Trunk, had consistently opposed this line. So Allan made “this French railroad scheme” into his own great cause. He subsidized newspapers that supported it and bought a controlling interest in the company’s stock. He travelled along the intended route, visiting priests and influential people and speaking in fluent French at public meetings. Before long, he had twenty-seven of the forty-five bleus on side—demobilizing more than half of Cartier’s army. At that point, Cartier buckled under and, to save his political career, promised the railway contract to Allan and his Canadian Pacific Railway.

Cartier had not only been reduced to a dependant but, with his declining health, was also in jeopardy in his own riding. To have any hope of holding his seat, he needed funds in large amounts. The only possible source was Allan.

The money did come in, and in staggering, unprecedented amounts. But it was too late. Cartier’s illness, finally diagnosed as Bright’s disease, was rapidly eroding his inexhaustible energy and making his judgments erratic. His legs ballooned and he was able to give only two campaign speeches, both times speaking from a chair. Other factors came into play. The ultramontanes, led by Bishop Bourget, were determined to make Cartier pay for the Conservatives’ treatment of Riel. Allan’s claim that Cartier had opposed a “French railroad” stuck in the public’s mind, and his opponent in the riding, an able young lawyer, was a strong candidate. On election night, Cartier was soundly defeated by a margin of three to one.

George-Étienne Cartier, “Brave as a lion,” in Macdonald’s phrase, lost his own riding to Allan’s outpouring of money against him. To get Allan and his money back onto his side, Cartier ignored Macdonald’s instructions and promised him the charter for the Pacific Railway. Illness took away first his judgment, then his life. (photo credit 14.5)

In one respect, Allan and Cartier were alike. Both were exceptionally self-confident, certain that they were right or that they could bring the situation back to the way it should be. In all else, they were strangers. Cartier lived life to the full, with lively parties, a mistress, a passion for bawling out songs and a well-stocked wine cellar. Allan kept life at a distance. Cartier was a passionate patriot; the Confederation pact between French and English was far more his than Macdonald’s, and Montreal’s long reign as Canada’s principal industrial and financial city was his gift to his people. Allan’s only interest was in himself. Cartier was a life force. Allan never had much to say: long after the Pacific Scandal, a federal civil servant who knew him asked whether he had made a mistake by getting involved in politics. After a long silence he replied, “Mebbe.”* Cartier was a big man, Allan a very brainy small one. And it is Cartier who is remembered.

A replacement riding was quickly found for Cartier by Bishop Taché, who persuaded Riel to give up the nomination he had secured in the Manitoba riding of Provencher. But his political career was already over. A month after the election, Cartier boarded the steamship Prussian (owned, inevitably, by Allan) on his way to London to become a patient of the world’s authority on Bright’s disease. At this time, Macdonald advised Governor General Lisgar that Cartier’s sickness was “incurable” and that he wasn’t expected to last a year.

The election over, Macdonald now turned back to the Canadian Pacific issue. From this time on, he would have to deal with it alone.

* American unions were more advanced: south of the border, the equivalent campaign was the Eight-Hour Movement.

† In one intriguing accomplishment, an early edition of the Ontario Workman ran a long extract from Karl Marx’s recently published Das Kapital—even though it would not be published in English translation until 1882.

* Much of the material in this section is drawn from Bernard Ostry’s groundbreaking 1960 article “Conservatives, Liberals and Labour in the 1870s,” in Canadian Historical Review.

† Witton lost his seat two years later, in the 1874 election. He made a “good transition” to the new Liberal government and was sent by them to a post in Vienna.

* The Canadian shareholders of record included Donald Smith, William McDougall and J.J. Abbott, the company lawyer and, much later, briefly prime minister, as well as a number of MPs. Not all were privy to Allan’s extraordinary scheme, but a number must have been.

* This anecdote is recounted in Pierre Berton’s National Dream.