The judicial lawmakers, not John A. Macdonald … are the real authors of Canadian constitutional law.

John T. Saywell, The Lawmakers

As the mid-1880s approached, Macdonald must have been supremely confident that his nation-building objective was within his grasp. All British North America, from the Atlantic to the Pacific and north to the Pole, had been added to the new nation—excepting only Newfoundland. Canada was now as large as the United States. The transcontinental railway was well under way and, fortunately, the National Policy had produced many of the new manufacturing companies and jobs Macdonald had promised so blithely. The North-West Mounted Police had forged good relations with most of the native people of the prairies, assuring incoming settlers of a peaceable environment. And Canadians had just re-elected him handily, extending his term in office to 1887.

In one vital respect, though, Macdonald’s nation-building project had already begun to falter and would soon decline. He would be astonishingly slow to realize what was happening, almost certainly because the cause was an institution peopled by individuals he admired unreservedly—the British legal system and some of its most distinguished judges.

From the early 1880s on, the members of Britain’s Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) would reinterpret the Canadian constitution (the British North America Act) in a way that would change its balance radically. Macdonald himself had composed most of the original text, and it had been signed by all the Fathers of Confederation and by the British government and parliament of the day. Now, these judges, who were three thousand miles away in London and knew nothing about Canada nor ever visited there, began to execute the single most intrusive act of colonialism in Canada’s entire post-Confederation history. They dismissed as irrelevant to their considerations any argument based on Canadian history, politics, customs or conditions. It was almost as if they were tinkering with a theoretical model of their own imagining. Yet they executed these changes with scarcely a word of complaint from Macdonald or from any Canadian politician, lawyer, scholar, journalist or public figure.

The JCPC’s decisions during Macdonald’s last decade in office, and later rulings based upon precedents set during this period, would constitute unconstrained judicial activism: that is, judges making the law rather than just interpreting it. Their activism caused the highly centralized federation envisaged by the BNA Act to be turned into one of the most decentralized such systems in the world. Among the measures of this condition are that more barriers to trade exist among the provinces in Canada than in any other federal nation, and that in contrast to the nearest equivalent, the contemporary system in the U.S., itself originally highly decentralized, Ottawa accounts for only about one-third of spending by all governments, compared to Washington’s two-thirds share, and is excluded from any say about education or the management of health care.*

Given that Canada is an attenuated nation divided by two official languages and distinct geographical regions, it would be reasonable to assume that so fragmented a system of governance could not possibly work. Yet it does, and by most international comparisons it works well. While the JCPC judges knew nothing about the country, their remote, abstract decisions may well have been in Canada’s best interests.

Certainly, it’s difficult to make the case that a more centralized federation would have fared better. The one clearly negative consequence was how long it took Canada to mature as a nation. Formal independence was achieved only in 1931 (by the Statute of Westminster),† Canadian citizenship in 1947, freedom from the arbitration of the JCPC in 1949, a national flag in 1965 and a patriated and fully Canadianized constitution in 1982. Despite the British constitutional theoretician A.V. Dicey’s declaration that “federalism is … legalism,” or endless legal arguments over who is responsible for what, perhaps Canada works largely because of Canadians themselves, their ingrained pragmatism, aptitude for compromise and readiness to listen to contrary views. If so, it’s possible that had the JCPC not intervened, Canadians would have figured out how to make the more centralized constitution that Macdonald and the Fathers of Confederation intended work as effectively for them.

The JCPC judges don’t merit all the blame. Canada’s constitution was thin. Unlike the U.S. constitution, it entirely lacked poetry; its only definition of purpose was that it was “similar in principle” to Britain’s constitution.* The BNA Act even lacked the quality of connectedness of its nearest equivalent, the Australian constitution, which declares in the preamble, “… the people of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland and Tasmania, relying on the blessing of Almighty God, have agreed to unite in one indissoluble federal commonwealth.” Only in 1982, when their constitution was changed radically by adding to it the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and was itself at last brought home, did Canadians possess a constitution that truly belonged to them—if, inevitably, not all of them, Quebecers most particularly.

For a full decade after Confederation in 1867, scarcely any harsh words were exchanged about the constitution’s meaning. The provincial governments were preoccupied with figuring out what they were, and because all the experienced politicians and civil servants were in Ottawa, looked to the capital for advice about the law. Edward Blake did attempt to stir up controversy when Macdonald offered “better terms” first to Nova Scotia and later to others, but he attracted little support in his own Liberal Party and none at all from the general public.

Yet Macdonald was careful not to overplay his hand. In 1868, he circulated to the premiers a memorandum describing how he intended to exercise the awesome power of being able to disallow provincial legislation—a hangover from Britain’s earlier right to disallow errant colonial legislation. To provincial applause, Macdonald pledged to exercise this right “with great caution and only in cases where the law and the general interests of the Dominion imperatively demand it.” During his first six years in power, Macdonald disallowed only five provincial acts, compared to eighteen by Alexander Mackenzie’s Liberal government over a similar span. In the case of the New Brunswick law abolishing Catholic separate schools, Macdonald refused calls to intervene, telling a Reverend Quinn in 1873, “the Constitution would not be worth the paper it is written on unless the rights of the Provincial Legislatures were supported.” The cure would have to be political action by local Catholics; the effect of any attempt by Ottawa to intervene would be that “all hope for the Catholic minority was gone.”

Several of Macdonald’s early steps towards centralization would have greatly benefited the country. As one, Canada might have had fewer and cheaper lawyers. In 1871, Macdonald asked the lieutenant-governor for the North-West to allow members of the bar in all the other provinces to practise in Manitoba. Nothing was done. One of his successful acts of centralization has been of unquestioned value. Although immigration was constitutionally a joint responsibility, Macdonald persuaded the provinces to let Ottawa make the decisions: as he told his Quebec friend Brown Chamberlin, the editor of the Montreal Gazette, “The Local Governments would do nothing, and the French were not very anxious on the subject.”* Even in his nation-building projects, he remained within the constitutional limits. The BNA Act made policing a provincial responsibility; Macdonald therefore limited the mandate of his Mounted Police to the North-West Territory, excluding Manitoba despite calls for the force by its lieutenant-governor. When one leading citizen pleaded for federal action to improve the schools, Macdonald replied that “we at Ottawa had no right of interference or supervision of any kind,” even though he believed in “a comprehensive system of education for the youth of the Dominion, based on broad principles and not on local prejudices.”

Macdonald’s interest was in nation-building, not in building up the national government by new social and economic legislation. Only with his protectionist National Policy of 1879 did he engage in legislation that might compete with provincial aspirations. At this time, Ontario alone had any such ambitions; in Quebec, social programs were the concern of the church—as one historian has observed, “the church was the state.”

Arguments about Canada’s constitution began with Macdonald’s return to power in 1878. The initiator was Ontario’s Oliver Mowat.

Macdonald had always known that disagreements between the two levels of government were inevitable. In an 1868 letter to Chamberlin, he agreed that “a conflict may, ere long, arise between the Dominion and the States Rights people.” He continued confidently, “The powers of the General Government are so much greater than those of the United States in its relations with the local Governments, that the central power must win.” Macdonald even wondered if the provinces might end up as enlarged municipalities, telling one correspondent that they merited no more attention “than the ruling party in the corporation of Quebec [City] or Montreal.”

Macdonald didn’t think of himself as a centralist; rather, he said he followed “the happy medium.” In another 1868 letter, he said that unlike Chamberlin, “an ardent Dominion man,” he felt he was “taking the middle and correct course” in relation to “the provincial magnates.” He nevertheless had no doubt about the “proper place” for the provinces: they should be subordinate to the federal government rather than sovereign within their own jurisdiction. Macdonald came by this view naturally; singular sovereignty was integral to the British tradition. Sir William Blackstone, the great eighteenth-century legal scholar, had laid down the precept that sovereignty had to be “a supreme, irresistible, absolute, uncontrolled authority.”

Macdonald’s view of the role of the federal government was clear: “We represent the interests of all the Provinces of Canada,” he told Justice Minister Alexander Campbell. His most explicit public description of his vision was his declaration in Parliament in 1882: “Sir, we are not half a dozen provinces. We are one great Dominion.” Laurier’s counter-vision, expressed three years later, was “we have not a single community in this country. We have seven different communities.”

Besides British history and legal theory, Canada’s own constitution confirmed Macdonald’s presumption. The clear objective of the Fathers of Confederation had been to create a centralized federation in order to avoid a northern version of the Civil War, precipitated, in their view, by the highly decentralized system in the United States. It was no coincidence that the BNA Act repeatedly used the word “union” rather than “federation.” At the same time, as a practical politician, Macdonald accepted that any attempt to create a British-style unitary state in Canada was impossible: in his words, Quebec’s concerns about its cultural particularities would have been “enough to secure the repudiation of Confederation by the people of Lower Canada.”

The powers of the central government, as set out in the BNA Act, were so extensive that, other than to have granted it the right to abolish the provinces (as happened in New Zealand), it wasn’t easy to imagine what else might have been ceded to the centre. Ottawa had the power to disallow or reserve (set aside) provincial legislation that, in its judgment, infringed federal jurisdiction. It could raise revenues by any form of taxation, and spend them in areas of provincial jurisdiction (if by practice rather than specific legal sanction). In a conscious reversal of the U.S. system, all powers not specifically assigned to the provinces resided with the federal government. It possessed the comprehensive override clause of “Peace, Order and Good Government.” It could designate any public undertaking as being “for the general Advantage of Canada.” The economy was to function as a single market. Unlike the original arrangement in the United States, the federal government had exclusive authority over banking and currency. As Macdonald saw it, the central government possessed “all the great subjects of legislation … all the powers that are incidental to sovereignty.” The only broad power granted to the provinces was the secondary one of control over “Property and Civil Rights.”

This lopsided division of powers was the work of the Fathers of Confederation. George Brown had declared that the provinces “should not be expensive and should not take up political matters.” At the Quebec City Conference, Mowat himself had proposed the clause that gave Ottawa the right to disallow provincial legislation, and he insisted that the Criminal Code be standardized, because “it would weld us into a nation.”

The Fathers may not have really known what they were doing. During the debates in the pre-Confederation legislature, an independent member, Christopher Dunkin, observed that as time passed, “all talk of your new nationality will sound but strangely”; in its place, “some older nationality will then be found to hold the first place in most people’s hearts.” Dunkin had foreseen the future: the “older” loyalties were to Britain or to historic entities such as Upper Canada or Nova Scotia. Confederation itself added little to any sense of pan-Canadianism. As Goldwin Smith commented in 1878, “Sectionalism still reigns in everything, from the composition of the Cabinet down to that of a Wimbledon Rifle team.” Then and for many decades to come, Canada’s condition was comparable to Italy’s; as that country’s nineteenth-century nationalist leader Count Cavour commented on the achievement of union, “We have made Italy, now we must make Italians.”

Not until the First World War, as a result of the sacrifices paid by its soldiers, would Canada begin to see itself as a society greater than the sum of its parts. In earlier years, little sense of nationhood existed, other than that provided by the stature that first Macdonald and after him Laurier achieved, and, as essential to national survival, that strange, stubborn refusal by Canadians to become Americans.

Macdonald understood this mood. He worried that the new nation had “no associations, political or historical, connected with it.” Just a few trace elements of such feelings existed. After Confederation, ships’ captains took to flying a Canadian version of the Red Ensign, with the national coat of arms in its fly, even though no official approval existed. The great national holiday was not Dominion Day, July 1, but Queen Victoria’s birthday, May 24. Macdonald, skeptical of emotion and sentimentality, did little to develop such associations and institutions. He failed to appreciate the disintegrative effects of the Long Depression, when harsh conditions turned people’s attention towards the immediate and the local. And he failed to appreciate the effectiveness of the emerging provincial champion—Oliver Mowat.

Mowat’s most evident political quality was his blandness—confirmation that, from Ontario’s beginning, bland worked: for a quarter-century, from 1872 to 1896, Mowat never lost an election, an all-time record. Modern Ontario dates from him, because in these years he steered through the transition from a mostly rural and small-town society to a mostly industrial and urban province. Above all, he made Ontario well governed—an attribute then unique among the provinces.

Physically, Mowat resembled a clerk—he was “desky,” in the taunt of the Conservative Mail. Eloquence was foreign to him. His best-remembered utterance is the ill-considered line, his slogan in his first, 1857 election: “Vote for the Queen and Mowat, not for the Pope and Morrison [his opponent],” causing him ever after to be vulnerable to the accusation of being anti-Catholic. He called himself “a Christian statesman” and drank not a drop. He also ran Canada’s most efficient and extensive patronage machine. Mowat’s principal political gift was inexhaustible guile, “a genius for reconciling duty and opportunity,” according to Globe editor John Willison. His determination was as inexhaustible: “He was a Mameluk when roused,” commented one senior minister.

Oliver Mowat, stubby and cross-eyed, was Ontario’s longest-serving premier and Macdonald’s most effective opponent. In a great put-down Macdonald once said what he most admired about Mowat was “his hand-writing.” Macdonald underestimated him, probably because Mowat had once been an apprentice in his law office.

Macdonald’s great mistake was to underestimate Mowat, his former clerk in his law office in Kingston. In debates, Macdonald could dance rings around him: on one occasion, when asked what he most admired about Mowat, he replied, “His hand-writing.” But somehow he missed the rigour and determination of Mowat’s campaign for provincial rights. Partly, Mowat was motivated by self-interest: by bashing Ottawa, he made it easier for Ontario voters to forgive his failings. But there was also an important principle at stake. The Liberals had long demanded provincial autonomy, principally for two reasons: the first democratic, to get government as near to the people as possible; the second populist, to get French Canada off the back of Ontario’s English-Canadian Protestants. Instead, after Confederation, George-Étienne Cartier’s bleus seemed to exercise as much influence as ever, if now from the vantage-point of Ottawa.

Once Mowat became premier in 1872, the exchange of letters between him and Macdonald was chilly, if polite. During the year that remained before the Canadian Pacific Scandal, they engaged in just one tussle. In 1873, two bills came before the Ontario legislature to permit the Orange lodges to incorporate. Catholics protested, and the provincial cabinet split over the issue. The bills passed eventually, and with Mowat’s approval, but he cannily convinced the lieutenant-governor to reserve the acts, so the responsibility for offending either the Orangemen or the Irish Catholics was transferred to Ottawa. Macdonald, describing himself as “too old a bird to be caught with such chaff,” lobbed the ball right back to Mowat. In the end, Mowat withdrew the bills, which pleased the Catholics but did not really offend the Orangemen, because he soon brought down general legislation allowing everyone to gain incorporation. Mowat had proved he was master at Queen’s Park, while Macdonald had confirmed that, in Ottawa, there was no one to match him.

One letter defined the real debate that would take place between these giants after Macdonald’s return in 1878. In a note to Mowat of January 7, 1873, about a dispute over whether Queen’s Counsels could be appointed by provinces, Macdonald commented that “each Province is a quasi-Sovereignty.” This statement directly contradicted the claim Mowat had made on his first day in office—that the provinces were fully sovereign within their own jurisdiction. For the next six years, peace prevailed while the Liberals held power in Ottawa; as soon as Macdonald was back, everything changed.

During the intervening five years, Mowat provided a fair amount of good government in the form of social and economic reforms. His most considerable accomplishment, though, was to prepare himself for constitutional battle with Macdonald. His preparations were tactically impeccable. Before attempting to decentralize power away from Ottawa, Mowat first centralized power within the province itself, so enabling him to speak on behalf of a united Ontario.

The Long Depression hit a number of Ontario municipalities hard. Mowat responded by setting up a Municipal Loan Board to extend relief to those seriously threatened. A side-consequence was to make the municipalities dependent on Queen’s Park and, no less agreeably, to expand Mowat’s opportunities to exercise patronage. Mowat went on to repeat this pattern in the fields of education, liquor licensing and agriculture. Ever more power got transferred to Queen’s Park, together with the numbers of Ontarians ready to say, “Ready, aye, ready,” when Mowat asked.

Macdonald spotted the threat immediately, describing Mowat as “that little tyrant who had attempted to control public opinion by getting hold of every little office.” By 1883, he was complaining that “the whole system of the Liberal Administration in the Province of Ontario has been centralized. They have taken the right of deciding everything connected with taverns and with the licensed victuallers; they have taken the clerkships of courts and the appointments of bailiffs.”

Mowat’s patronage machine may well have been the most efficient ever assembled in Canada. It was comprehensive: Willison wrote in the Globe, “For over a generation, not a Conservative was appointed to the public service in Ontario.” And it was intensive: unlike Macdonald, Mowat insisted that appointees do their public duties properly, even as he maintained a close eye on what they were doing for the party. As well, he kept his own hands at a respectable distance from it all, as the real work was done by party secretary W.T.R. Preston, who came to be known as “Hug the Machine.” Mowat himself made no apology, declaring that “the right of patronage” belonged to “the party in power.”

While he was premier, Mowat always spoke only about Ontario—he never gave a speech on general dominion issues nor showed any interest in events beyond Ontario’s borders. The one brief exception was a conference of dissident provinces held in 1887 at the call of Quebec premier Honoré Mercier. Mowat attended and steered through resolutions calling for more money from Ottawa and more power over provincial jurisdiction. Nothing happened to any of these demands, and Mowat never again spoke about provincial rights in general.

Although he has entered the history books as “the father of provincial rights,” Mowat was really only the father of Ontario’s rights. Indeed, the more autonomy Mowat gained for Ontario, the harder it would be for Macdonald to redistribute to other provinces any of the revenues sent to Ottawa by prosperous Ontario. As one of his senior ministers, Christopher Fraser, put it, Ontario would not be “the milk cow for the whole concern.”

Mowat’s real role was as the father of what historian H.V. Nelles has called “Empire Ontario.” The long-term effect of this accomplishment, though, would be the exact opposite of Mowat’s intent: once confident of their province’s autonomy, Ontarians became enthusiastic advocates of a coast-to-coast national identity.

In the summer of 1878, Ontario took a long step towards becoming Empire Ontario. On August 3, an inquiry set up years earlier by Alexander Mackenzie to resolve a long-running argument over the location of Ontario’s western boundary abruptly announced its decision. The boundary line, the commissioners ruled, should be drawn well west of the Lakehead (today, Thunder Bay), adding 110,000 square miles to the province. This decision was made after only three days of hearings and with no explanation given to justify it.

Ontario’s western boundary had been an issue ever since the North-West entered into Confederation. The first inquiry, initiated by Macdonald in 1872, fell apart in internal wrangling. The second, by Mackenzie, did nothing until Mowat realized that Macdonald might well win the 1878 election. Mackenzie revived the commission, which came down resoundingly on Ontario’s side. When Macdonald gained office two months later, he dismissed its findings. He argued that the interests of Manitoba should be taken into account, its attraction to Macdonald being that its government was Conservative. Two provinces now claimed control of the same territory. Both appointed magistrates in the principal community, Rat Portage (today, Kenora), and sent out policemen, who at one point began arresting each other. After more wrangling, Macdonald and Mowat agreed to refer the issue for a binding decision by Canada’s highest legal body, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

Macdonald had helped to make it possible for the JCPC to exercise this authority. Canada’s court of last resort did not have to have been a handful of British judges sitting in a small room in London. An alternative existed, the Supreme Court of Canada, but in the coming contest for judicial supremacy, it would lose out to the JCPC—and an intervention by Macdonald that hobbled its chances of succeeding. He in fact strongly supported the creation of a Supreme Court. Twice during his first term, he had introduced the necessary legislation but set it aside for other priorities. After the Liberals gained power, Télesphore Fournier, the new minister of justice, introduced similar legislation. Macdonald applauded the initiative, and approval seemed certain.

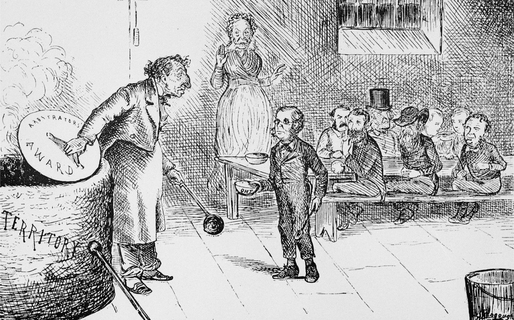

This Grip cartoon shows Ontario Premier Oliver Mowat asking for “more” in the manner of Oliver Twist and, by a decision of the British judges, getting it in the form of a major increase in Ontario’s size. (photo credit 24.1)

At this point a minor historical figure changed history’s course: a backbench Liberal MP, Aemilius Irving, moved an amendment that the Supreme Court should become the sole arbiter of Canadian law, including constitutional cases.* If this Clause 47 had been accepted, the role the JCPC performed all over the Empire would have ended in Canada. Macdonald’s feelings about Britain retaining its oversight over Canadian law were mixed. He once told W.R. Meredith, the Conservative leader in Ontario, that “Canada is so separated by position from England that it may be considered another country and its legislation therefore … a matter of indifference to the Mother Country.” Yet he also informed Judge James Robert Gowan that Canada’s laws “should in principle be the same as in England … [giving] the inestimable advantage of having English decisions as authority in our Courts.”

During the Commons debate, Macdonald, at times sounding as though he had imbibed too liberally, declared passionately that Irving’s Clause 47 threatened the “golden chain” linking Canada to Britain. Eliminating it could “excite in England” a conviction that Canada was gripped by “an impatience … of even the semblance of Imperial authority.” The bill still passed.

Alerted by Macdonald’s intervention, the Colonial Office sent worried inquiries across the Atlantic. By another accident of history, Edward Blake, a strong nationalist, had just returned to Mackenzie’s cabinet as minister of justice. He strongly favoured Clause 47, and by exerting his considerable legal skills persuaded the Colonial Office that Canada did indeed have the right to limit, even to abolish, appeals to the JCPC. At this point Lord Cairns, Britain’s Lord Chancellor, joined the dispute. Highly regarded as a legal scholar, he concluded that Macdonald had been right and that passing Clause 47 would be “equivalent to a complete severance in its strongest tie between our Colonies and the Mother Country.” There was now a real risk that London might disallow the legislation, provoking a first-class transatlantic political row.*

The problem was resolved by an exercise in high-level Imperial chicanery. By now, the Mackenzie government had already begun setting up the Supreme Court; to back down would be a severe humiliation. Hastily, Blake was invited to present his case to Cairns in London. The two engaged in high-stepping legal arguments and arrived at a solution: Canada would complete the establishment of a Supreme Court, but both parties agreed to treat Clause 47 as inoperative, enabling the JCPC to continue as if nothing had happened. Blake regretted backing down, saying in a Commons debate, “The true spirit of our Constitution, can be made manifest only to the men of the soil. I deny it can be well expounded by men whose lives have passed, not merely in another, but in an opposite sphere of practice.” Canadian judges, he astutely remarked, “such as they are, they are our own.” Blake was more than half a century ahead of his time. In the meantime, Macdonald would learn that the “golden chain” he so favoured could also choke.

For four years, the Supreme Court had the field largely to itself, with constitutional cases going first to it. During this span, all but one of its six constitutional decisions favoured federal jurisdiction over provincial—a striking consensus given that all its judges had been appointed by Mackenzie’s Liberal government.

As a harbinger of the future, Mowat appeared before the Supreme Court in one case, declaring, “I claim for the Provinces the largest power they can be given,” and adding, “It is the spirit under which Confederation was agreed to.” He lost that case. In another, Macdonald’s first appointee to the court, Justice John Gwynne, described the provinces as “subordinate bodies … having jurisdiction exclusive though not ‘Sovereign.’ ” Historian John Saywell reckoned that “in time, the Supreme Court, in spite of its shortcomings, would have shaped the federal constitution.… But there was no time.” By 1879, the JCPC was ready and eager to decide what Canadians should do.

The change was quick and dramatic. Appellants, particularly Mowat, took to submitting their cases directly to the JCPC, bypassing the Supreme Court. Before long, the British court was overruling one in two of the Supreme Court decisions. Inexorably, the Supreme Court’s stature and credibility went into decline, where they would remain for two-thirds of a century.

The JCPC met the cardinal requirements for institutional credibility in Britain: it was ancient, and it was eccentric. It could be traced back to the fifteenth century or further. Its members sat around a circular table rather than an elevated long one, and it wasn’t truly a court that issued judgments but a committee that gave advice to the monarch—so its members wore neither gowns nor wigs. (Always, one chair around the table was left empty so the king or queen could attend; none ever did.) In substance, however, it was one of Britain’s highest courts, hearing cases from 150 colonies as well as the Admiralty and the Church of England.*

The JCPC had decided defects for the role it was about to perform for Canada. No member knew anything about Canada or about federalism—Britain itself providing no guidance, since it was a unitary state and had no written constitution. It relied unduly on advice from Judah P. Benjamin, the former attorney general for the Confederate States of America, who had fled to London after the Civil War, and who, inevitably, was a strong advocate of states’ rights. The two members who moved it furthest along the decentralist path—lords Watson and Haldane—were both Scots, and favoured keeping their nation as far apart as possible from English entanglements. Lastly, Imperial Federation was much in vogue at the time, and judges like Watson and Haldane, in anticipation of the day when the Empire could no longer be held together by force of arms, may well have been using Canada as a test case for Imperial devolution.

The JCPC’s leading initial authority on Canadian affairs was William Watson. A conservative Conservative, he had had an undistinguished early career and was the second choice when appointed to the JCPC in 1880. Ennobled as Lord Watson, he was the decisive force in determining Canadian cases until his death in 1899. As his successor, Haldane, wrote of his role, “In a series of masterly judgments, [Watson] expounded and established the real constitution of Canada.” In other words, he engaged in judicial activism. Haldane described him as “a statesman as well as a jurist, [who] fill[ed] in the gaps which Parliament has deliberately left in the skeleton constitution and laws.” About his own later interventions, most particularly those which contracted the meaning of the “Peace, Order and Good Government” clause to near nullity, thereby reducing Ottawa to near impotence during the Great Depression, Haldane explained without apology that the JCPC was “giving administrative assistance.”

Compared to the Supreme Court, the JCPC possessed considerable advantages. It published no dissenting opinions, so giving itself an aura of infallibility, and it wrote off Canadian history and political practice as “of great historical value but not otherwise pertinent.” In effect, its judges interpreted the BNA Act as an ordinary statute, freeing themselves from the constitution’s context and dealing only with the words used in it, and how they chose to interpret them.

Citizen’s Insurance Co. v. Parsons, in 1881, was the JCPC’s first major Canadian constitutional case. It confirmed the Supreme Court’s earlier dismissal of an Ontario claim that “the provincial parliament has the exclusive right to create within the province, rights of property.” While the judgment favoured Macdonald’s constitutional position, Justice Gwynne warned him that the arguments presented in the case could be “the thin edge of the wedge to bring about provincial sovereignty[,] which I believe Mr. Mowat is endeavouring to do.” Macdonald ignored Gwynne’s warning. It is possible that Mowat’s ultimate constitutional ambitions went further than sovereignty within Ontario’s own borders. At one JCPC hearing, Mowat’s counsel informed the judges, “The provinces are virtually separate countries.… Each is a separate state.” Although Mowat never made this claim, Haldane would later describe the provinces as “independent kingdoms over which the Dominion has little control.”

For a brief span, it seemed that Macdonald might have been right to be so confident. In 1882, Russell v. the Queen came before the JCPC. Charles Russell of Fredericton, New Brunswick, had been fined in magistrate’s court for selling intoxicating liquors without a provincial licence, despite his argument he was justified because the federal Canada Temperance Act regulated the liquor trade right across the country. Russell fought back through all the courts. The JCPC’s ruling could not have pleased Macdonald more; it rejected the claim that the Temperance Act breached provincial jurisdiction and anchored this finding in Ottawa’s “Peace, Order and Good Government clause.” Macdonald gleefully told Campbell, “My opinions are strongly supported.… This decision will be a great protection to the Central Authority.”

One year later, the case of Hodge v. the Queen changed everything. Archibald Hodge, a Toronto innkeeper who had a licence under the federal Temperance Act, had appealed a provincial fine that he incurred when he allowed his patrons to play billiards past Ontario’s Saturday closing hour of 7 p.m. After hearing the arguments, the JCPC ruled, on December 15, 1885, that provincial powers under Section 92 of the act were in no way diminished by the federal powers in Section 91. Rather, the provincial legislature was “supreme and has the same authority as the Imperial Parliament or the Parliament of the Dominion would have under like circumstances.” The provinces were not subordinate to Ottawa, and within their prescribed area of jurisdiction were in fact supreme.

This decision would lead historian W.L. Morton to conclude, “On Mr. Hodge’s billiard table, then, the Macdonaldian concept for Confederation was baulked.”

Afterwards came the deluge. The single most definitive confirmation of the new order, in Liquidators of the Maritime Bank of Canada v. Receiver-General of New Brunswick, was made public in 1892, one year after Macdonald’s death (although the case had passed through the lower courts for years earlier). The JCPC’s judgment, written by Watson, held: “The object of the B.N.A. Act was neither to weld the provinces into one, nor to subordinate the provincial governments to a central one”; rather, the provinces’ powers were “exclusive and supreme.” The provinces were sovereign—and not just within their jurisdiction as enumerated in Section 91, but over an ever-expanding list as the judges progressively diminished the reach of the federal “Peace, Order and Good Government” override clause and expanded the provinces’ “Property and Civil Rights” equivalent.

Macdonald never complained publicly about this rewriting of the constitution by means of radically reinterpreting it. He did once burst out in exasperation, “Mowat has all the luck.” The truth was, though, that Mowat made most of his luck himself.

Macdonald never quite seemed to understand what was going on. He sent able lawyers across to London to represent the federal side, Alexander Campbell and D’Alton McCarthy among them. Mostly, though, he remained detached. In a letter to Gowan while in London in 1884, Macdonald mused, “I agree with much that you say about the Judicial Committee of the P.C.—but we must put up with it—I don’t move in the legal region at all here.” He reacted politically, worrying about the next election rather than about the next case due to be heard by the JCPC. Most simply, Macdonald, in his reverence for the law and for Britain, could not bring himself to say out loud that some of the best judges in Britain might have been grievously wrong for a cluster of reasons, the most decisive being that they knew nothing about Canada, nor were in the least bothered by this shortcoming.

One major attempt has been made since then to claim that the JCPC judges did care. In an influential 1971 article, the distinguished constitutional scholar Alan Cairns argued, “It is impossible to believe that a few elderly men in London … caused the development of Canada in a federalist direction that the country would not otherwise have taken.” Instead, the JCPC’s rulings were “not in isolation of deeply rooted, popularly supported trends in Canada.”

This proposition is unpersuasive. The single instance Cairns cited of the JCPC being in accord with “popularly supported trends” was the hero’s welcome given Mowat when he returned from Britain in 1884 after winning a favourable ruling on Ontario’s western boundary. That same year, though, Macdonald received as rapturous a welcome in Toronto for the anniversary of his fortieth year in politics. Overlooked is the one objective measure of popular sentiment that does exist: the 1883 election in Ontario, when Mowat made his constitutional quarrel with Macdonald the centrepiece of his campaign. Never before or afterwards did Mowat have a harder time, and his majority was reduced from twenty-five to nine. This result doesn’t mean that Ontarians preferred Macdonald’s more centralist policy; it simply means that, then as now, Ontarians had little interest in constitutional quarrels.

Canada’s constitution was indeed given “a new form” (Haldane’s phase) by “a few elderly men in London,” as Saywell wrote in his seminal but neglected work, The Lawmakers: Judicial Power and the Shaping of Canadian Federalism. They inflicted on Macdonald his one clear nation-building defeat. Yet he still implemented almost all his nation-building agenda. It has to be added that things haven’t turned out at all badly in the decentralized nation that the JCPC judges concocted in place of Macdonald’s vision for it; also, that even though nothing could have been further from the British judges’ intentions or interests, Canada’s decentralization (“provincialisation” would really be a more accurate term) is one of the political characteristics that clearly differentiates the Canadian political system from America’s.

* The only federations which may be more decentralized than Canada’s are those of Switzerland and Belgium.

† Canada achieved effective independence as an “autonomous community” five years earlier, by the Balfour Declaration of 1926.

* The “Peace, Order and Good Government” phrase, while now accepted as the constitution’s essence, was originally merely standard wording inserted at that time into the constitutions of a great many British colonies.

* Most provinces have now negotiated joint agreements with Ottawa, Quebec being the first to have done so.

* Irving was following up a suggestion by Justice Minister Fournier in his opening speech when he’d said he would “very well like to see a clause introduced declaring that this right of appeal to the Privy Council no longer existed.”

* One of Cairns’s arguments was that only the JCPC itself could decide whether Canada had the right to end appeals to it. He was correct, technically: in 1949, it was accepted that the JCPC could only be abolished if it first consented to its own extinction.

* The JCPC is still in business today, hearing cases from such places as Bermuda and the Falkland Islands.