The Americans may say with truth that if they do not annex Canada, they are annexing Canadians.

Goldwin Smith

The Long Depression resumed around the end of 1883. This time, it wasn’t precipitated by some financial panic or corporate scandal but just seemed to happen. International prices for commodities such as grain and lumber began to fall, touching off a domino effect in real estate, and in quick succession banks tightened credit, manufacturers cut back, unemployment increased and wages dropped. From Canada’s perspective, there was one fundamental difference between this downturn and the first phase of the Long Depression from 1873 to 1878. It affected Canada much more deeply than the United States until 1893, when a financial panic precipitated an all-out crash below the border.

In many respects, the United States still boomed. The Gilded Age was in full flower, powered by mass immigration, the settlement of the West, an outburst of technological creativity and the acquisitive energies of tycoons such as John D. Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Andrew W. Mellon and Andrew Carnegie. In between a series of small recessions, the country expanded, and by the end of the century its manufacturing output exceeded that of Britain, Germany and France.

Never has the contrast between Canada and the United States been wider. In historian J.M.S. Careless’s phrase, the span from the mid-1880s to the turn of the century was Canada’s “age of failure.” Its effects were felt more acutely than those of all the earlier downturns because the growing class of urban industrial workers were so vulnerable—unlike farmers, unable to grow their own food, and few owning their own houses. Although the depression’s scope was global, its psychological and political impact on Canadian society went especially deep, and it came to induce a sense of national failure. Because Americans were faring so much better, Canadians began to question the national assumption that their way—the British way—was superior. They came to doubt their society and themselves more than they ever had before, or ever would again, even during the Great Depression of the 1930s, when, while many despaired for their personal future, few doubted their country’s ability to exist.

Although not a “failed state,” Canada towards the last decade of the nineteenth century came perilously close to failing its people in material terms, and failing to fulfill the dreams once held for it by visionaries such as D’Arcy McGee and Charles Mair. Goldwin Smith spoke for the opposite view of the country’s prospects when he said that Canadian nationality was “a lost cause” and “the ultimate union of Canada with the United States appears now to be morally certain.”

There was a particular reason for Canada’s gloom. At a time when most measures of economic progress were imprecise, the one exception was population counts. Censuses were widely believed to be scrupulously accurate, and these showed that through the last two decades of the nineteenth century Canada’s population had changed little, edging up from just over 4 million to just over 5 million. Given the enormous increase in its physical size and the high rate of immigration earlier in the century, this was deeply disappointing. But for the fecundity of Quebec wives and their obedience to their curés, the population might even have contracted. Every year, more people left the country than entered it. Canada’s net immigration numbers were lower comparatively than those not only of the United States, but also of its “new nation” rivals—Australia, New Zealand, Argentina and Brazil. During Macdonald’s last decade, 1880 to 1890, net out-migration would reach 207,000, an all-time record. By the century’s end, more than one million Canadians were living in the United States, close to one for every five at home; many more Canadians had probably moved south but were living there invisibly.

This situation applied most depressingly in the North-West, where the greatest influx of immigrants had been anticipated. By the end of the century, the population there was around a hundred thousand European Canadians—little different from Prince Edward Island. The long-dreamed-of transcontinental railway was being built, but few people were arriving to use it.

No immediate cure existed for this failure. Immigrants to North America overwhelmingly headed to the American West, attracted by the milder climate and higher level of development, and they would keep going there until 1892, when the frontier was officially declared closed. There were some immigration success stories here. The Icelanders did well as farmers, and their numbers increased to seven thousand. Mennonites also did exceptionally well, in about the same numbers. Jews driven out of Russia by pogroms, and later from Poland and Austria, fled to Western Europe, with some continuing on to Canada; they were traders rather than farmers, so most soon left the prairies for Winnipeg and other towns. Lastly, a number of French Canadians who had moved to the United States were attracted back by the promise of state-supported separate schools in the West.

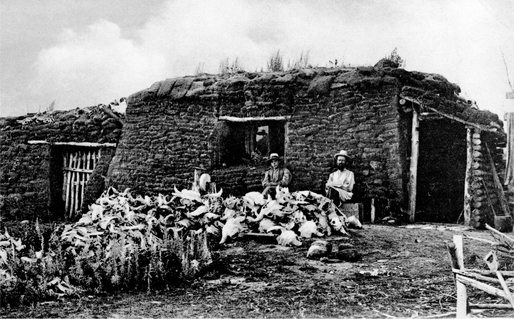

For years after the buffalo were gone, some people on the prairies made a living by gathering their bones and dung. For lack of wood, dwellings were made of sod. The hardness of pioneer life is confirmed by the fact that this is described as “better” than what went before. (photo credit 25.1)

Attempts to attract large-scale emigration from Ireland failed, however, despite these separate schools. Irish nationalists now saw Canada’s attempts to entice its people as “forcing the Irish into Exile, at the instance of the [British] Govt., or the Landlord,” as Macdonald put it in one letter. Nothing would change until the first decade of the twentieth century, when a combination of rising grain prices and the closure of the American West sent immigrants pouring into the prairies. Soon, Laurier would be able to predict that the twentieth century might belong to Canada.*

Macdonald missed this moment of national reaffirmation. From the mid-1880s until his death in 1891, his principal nation-building task would be to keep the nation going—and together—until things turned around.

Macdonald was renowned for his resilience and capacity for optimism under the bleakest of circumstances—qualities that sustained him through the disappointments of his personal life. He also had some priceless assets. His guile and wiliness had been refined by years of experience. And he had a hold on the affections of Canadians that few other leaders would ever approach.

Yet time ticked inexorably by. When Macdonald celebrated his seventieth birthday in 1885, at a party at the Windsor Hotel in Montreal, he quoted from Shakespeare’s As You Like It: “My age is as a lusty winter / Frosty but kindly.” Aches and ailments had become part of his daily condition, with an occasional warning of something more drastic ahead. “I am breaking down. I can’t conceal it from myself, perhaps not even from my friends,” he told a civil servant after the end of the 1883 session. Macdonald still viewed life with too much sardonic amusement to ever become a grumpy old man, but he was beginning to get out of date: in 1883, he referred to the North-West as “a Crown Colony,” as though it still belonged to Britain. He complained to Charles Tupper about his own cabinet: “We are too old.” His administrative practices became slapdash. After 1883, he “developed the habit of putting some of the most perplexing files aside, to be looked at later. These, in turn, got buried by other files,” Joyce Sowby writes in her master’s thesis. He was entering his “Old Tomorrow” era.*

Macdonald was now trapped in the office he had held for so long. Stepping down had become almost impossible: he had no successor, and too many of his supporters depended on him. More and more, the people around him told him what they guessed he wanted to hear rather than what they genuinely believed.

As the depression continued, sectarianism raised its ugly head. Desperate people needed scapegoats to explain their economic misery. In Ontario, annoyance grew that its hinterland colony, the North-West, had been stolen from it by Macdonald’s creation of the province of Manitoba. In the West, the view took hold that French Canadians were running the country, because Macdonald depended, permanently, on the bloc of bleu MPs. And soon Quebec would join the ranks of disaffected provinces. There was more to come: a rebellion in the North-West; a serious risk of Canada’s first Indian war; a second outbreak of separatism in Nova Scotia; the rise of a “nativist” movement hostile to all immigrants, especially those from China; a contraction in the government’s revenues just when the Canadian Pacific Railway needed to be rescued from bankruptcy; and a large number of prairie Aboriginals who needed to be saved from starvation.

It’s been said that Macdonald called Canada “a hard country to govern.” The only evidence he ever did say this is an unsubstantiated claim by Saturday Night magazine editor Hector Charlesworth in his memoirs of 1927. In fact, the initiator of the phrase was Laurier, who wrote in a 1906 letter to the Globe’s John Willison, “This is a difficult country to govern.” True beyond doubt is that Canada had never been harder to govern than it was during Macdonald’s last decade. Most of the time he was on the defensive, hanging on, much as was the country. He made some bad mistakes. But he never made the one mistake that would have mattered: he never gave up.

There is, though, a clear and unfamiliar note of defeatism in a letter he wrote on November 3, 1884, to Judge James Robert Gowan from London, where he had gone as much as anything to get away from it all. “I did run away as you supposed, from dyspepsia and worry—having at the same time enough public work to do to keep me from rusting on this Side,” he confessed. However, he had seen his physician, who told him he was “wonderfully Sound” and that he could not discover the door “through which my Soul will some day escape for realms unknown.” Eventually, Macdonald recovered his customary good spirits, returned home and went to work.

Among the effects of the return of the Long Depression was the first appearance of prairie populism on the national stage.* Western alienation dates from this time, as does the West’s sense of itself as a distinct region rather than a hinterland extension of the old Canada. Western populism would have manifested itself eventually anyway, because it suited the temper and topography of the area: when space is almost limitless, individuals all shrink to the same size. Hard times, though, quickened its appearance on the national stage.

The movement began in Brandon. On October 19, 1883, a settler named Charles Stewart, who had graduated from Cambridge University, wrote to the local Sun calling for a protest meeting “to obtain for ourselves that independence which is the birth right of every British subject.” Out of this came the Manitoba and North-West Farmers’ Union, which held its inaugural convention in Winnipeg on December 19 that same year. The gathering agreed to a Declaration of Rights calling for an end to Ottawa’s disallowance of local railways, removal of high National Policy tariffs on agricultural equipment, and the transfer to the province of control over Crown lands. The declaration was sent to Macdonald in Ottawa; he paid not the least attention.

A second convention, in Winnipeg in March 1884, approved an “anti-immigration” resolution urging that potential immigrants to Manitoba be asked not to come until Ottawa had settled the West’s grievances. This excess, worsened by excited talk about separation, cost the movement its credibility. A new organization, a Protective Union, took over and launched an innovative program to buy up members’ wheat, ship it in bulk to Ontario and use the profits to buy binder twine in large quantities for its members. An Ontario manufacturer won the contract, though, provoking protests against “Eastern domination.”*

The real causes of the difficulties in the West were far beyond anyone’s reach. A worldwide surge in wheat production (in the United States, South America and Australia as well as Canada) pushed down prices, from $1.21 a bushel in 1880 to as low as 81 cents by 1888. The new agricultural machinery—such as Massey-Harris self-binders and steam-locomotive threshers—improved productivity, but, because bought with bank loans, made farmers more vulnerable to price declines and crop failures. Populism fed on the basic truth that the prairie pioneers had it extraordinarily hard: time and again, the frost came early, and droughts and locusts ravaged the land. The necessary techniques for dry-land farming would not be developed for years. In the meantime, one song popular on the prairies went, “This country’s a regular fraud, O, / And I want to go home to Mamma.”

Right from the start, western populists identified the people they held responsible for their troubles: “For the discontent which is keeping out immigration, for the hideous robbery to which people are daily subjected by the extortionate railway rates,” said the Manitoba Free Press, “Sir John Macdonald and his ministers alone are to blame.” In fact, after the turn of the century, as soon as grain prices rose and immigrants came, the West roared off on a three-decade-long boom. But this earlier experience gave westerners a target to unite against. As Frank Oliver, editor of the Edmonton Bulletin, put it, “The idea that the North-West is to eastern Canada as India is to Great Britain is one that will, if not abandoned, lead to the rupture of confederation.” Within Confederation there was now a lusty, brawling newcomer.

This western discontent was expressed most loudly in the north of present-day Saskatchewan. There, the CPR had abruptly switched its line far southwards, making Regina the territorial capital rather than North Battleford. The region went doubly into a depression. A Settlers’ Union was formed in Prince Albert, the largest town, and outraged resolutions were passed and sent to Ottawa. There, they vanished. The settlers became even more enraged. The same anger arose among a particular group of westerners living nearby in an area known as the South Branch of the Saskatchewan River. Its principal community was known as Batoche.

The Métis had been moving there, mostly from Red River, since the early 1870s, hoping to find buffalo farther west and a place in the North-West that was not English and Protestant. A settlement practice of the Métis—derived from Québécois settlements along the St. Lawrence River—was that their lots were long and narrow, fronting directly onto the river, rather than the square homestead properties standard everywhere else.

Batoche was in no way a fancy community, but neither was it impoverished. Most of its houses were flat-roofed log cabins, with buffalo hides stretched across the open door and windows. The first issue of the Saskatchewan Herald described it as “large and very flourishing.” The home of its most successful trader, with its “six roomy bedrooms sumptuously furnished with marble-topped dressers,” was regarded as the finest house west of Winnipeg. Another trader had installed a billiard table and, for his wife, a hand-operated washing machine. He was known as Gabriel Dumont, a legendary buffalo hunter who now operated a ferry across the Saskatchewan River at Batoche.

Still, it was an unsettled community. Its people were French and Catholic, and Métis. Many were illiterate and spoke little English. Despite disadvantages, indeed because of them, they possessed a sense of collective rights. This condition, together with their traditional preference for their elongated lots, complicated the task of settling their land claims. Early in 1884, a solution seemed imminent when a lands inspector, William Pearce, visited and suggested that square lots already surveyed be subdivided to create rectangular ones. For reasons now unclear, the Métis were not satisfied—and officials took no follow-up action. Historians Bob Beal and Rod Macleod suggest that the “Metis and their priests misunderstood the government’s land regulation and that compromises might have been worked out.” They continue that “the government had seemed to ignore the Metis,” who in turn assumed “it was up to the government to make rules that … coincided with their demands.”

The root problem was quite different—and likely impossible to resolve. The Métis’ main economic activity, the buffalo hunt, ended with the vanishing of the once-huge herds. Simultaneously, their subsidiary economic activity as freighters and teamsters on the riverboats and in convoys of Red River carts was being displaced by steamships and the railway. This change of life mattered incomparably more than difficulties over settling land claims, but the land-claim issue became the emotional focus for all the Métis anxieties. Pleas and petitions went out to Ottawa, but there disappeared.

In March 1884, some twenty-five South Branch Métis gathered to discuss what should be done. The most decisive was Gabriel Dumont. He told the others they should take matters into their own hands and “force the government to give us justice.” A decision was reached to bring in an expert to argue their case with Ottawa.

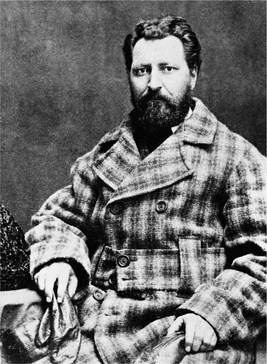

The expert they selected was someone they knew well: Louis Riel, now a teacher living on St. Peter’s Mission in the back-country of Montana. A delegation of four, headed by Dumont, made the six-hundred-mile horseback journey to visit him. Riel listened to their story and their request that he go back north with them, and he said he would give his answer the following day. When dawn broke, he agreed he would return. Now forty, he was plumper than he had been and had grown an impressive reddish-brown moustache. He even had a hardiness about him, probably because for the first time in his life he had gone out with the Métis on buffalo hunts. He had also married a Métisse named Marguerite and was the father of two young children.

Two aspects of this encounter would have lasting importance. Although three of the four visitors were French Métis, one was an English Métis. But there was no representative from the largest of all the prairie groups, the Aboriginals, nor any representative of the white settlers. The other distinction resided in Riel himself. In explaining to the quartet why he needed a day to consider their proposal, he had used a curious formula. The delegation had arrived on June 4, he said, so God had sent him a message by dispatching “four of you who have arrived on the fourth and you wish to leave with a fifth.” He concluded: “I cannot answer today. You must wait until the fifth.” The Riel who returned with them was no longer the man they had once known in Red River. This Riel now received messages directly from God.

The Riel who came back in 1884 to help the Métis achieve their land claims looked like the Riel of old, strong and bulky with piercing eyes. But he now had a family to care for—his wife, Marguerite, his son, Jean-Louis, and his daughter, Marie-Angélique. The more radical difference was that he was now fulfilling a “divine mission”; among the Métis of Batoche he could find a congregation that believed in it, too. (photo credit 25.4)

For the time being, however, all that mattered was that Riel was coming home.

* Laurier made his famous prediction in a speech to the Canadian Club of Ottawa in 1904.

* This nickname is often credited to Indian leaders such as Big Bear or Poundmaker or Crowfoot, but no supportive evidence exists. Macdonald took it in good heart: asked what title he would take if the current rumour he was to be offered a peerage was correct, he answered, “Lord Tomorrow.”

* It can be argued that its first expression was Riel’s uprising of 1869–70, though that was really an expression of Métis, rather than prairie, populism.

* Charles Stewart, the original protester, became an ardent separatist, prompting Protective Union moderates to “secede” Stewart from the hall—into a snowbank.