We thought we saw an open path

On which rare joys await.

O foolish we, that thus had hoped!

Such lines no land shall have;

This poor old Canada now sinks,

Back into her old time grave.

“Troubadour,” writing to Sir John A. Macdonald

In the summer of 1886, Macdonald began his picnic parade across Ontario once again, now accompanied by his new star, John Thompson. The justice minister was impressed by Macdonald’s skill and energy; he told his wife, Annie, how Macdonald would “shake hands with everyone & kiss all the girls.” He was not so keen on the picnics, which were “nothing but a lot of people walking about a field and some nasty provisions spoiling on a long table in the sun.” Still, things having gone better than expected, Macdonald dissolved Parliament and set the election date for February 22, 1887. A few days later, Honoré Mercier became premier of Quebec, at the head of a government of nationalists and Liberals, and joined actively in the campaign.

Macdonald still won handily. His majority dropped from sixty-eight to thirty-seven, but that was ample. Inevitably, he lost ground in Quebec, but even there just stayed ahead, thirty-three to thirty-two. Canadians still liked and trusted him—and certainly preferred him to the aloof Edward Blake. By June, Blake had resigned; Macdonald regretted his going, because, as he said, “We could not have a weaker opponent.” Blake’s self-chosen successor was still a long way from being a national figure, yet he clearly possessed natural political talent. He was Wilfrid Laurier, who had learned a lot about leadership by observing Macdonald carefully. For the first time, Macdonald faced an opponent of real mettle*.

The 1887 election victory would turn out to be the last bit of good news Macdonald heard for the next four years.

His difficulties had begun to multiply a few months earlier when, near the end of the 1886 session of Nova Scotia’s legislature, the new premier, William S. Fielding, put a most unusual motion before the mentors: the best interests of all of the Maritime provinces, he claimed, would be advanced by “withdrawing from the Canadian Federation and uniting under one Government.” Once again, Nova Scotians appeared to want out.

What the province really wanted was, again, “better terms”—in other words, more money. Fielding, a former newspaperman in his mid-thirties, was pursuing his goal with considerable skill. His appeal to local patriotism gave his Liberals an unbeatable issue in the election, winning him twenty-nine of the thirty-eight seats. And his call for separation was risk free, because there was no way the other Maritime provinces would ever join Nova Scotia as junior partners in a regional union, in or out of Confederation. Macdonald had already rejected Fielding’s request, and to strengthen his hand had called Charles Tupper back from London. The presence of the “Cumberland Warhorse,” together with local anxieties that separation (or repeal, as it was called) might actually happen, earned Macdonald fourteen of Nova Scotia’s twenty-one federal seats in the election. Soon after, Fielding cancelled his motion. As the Halifax Morning Herald put it, “The legislature of Nova Scotia consigned the repeal jackass to the silent tomb.”

Nevertheless, Fielding and his Liberals were still the provincial government.* And a conviction of unfairness had taken hold among the population, one that would last for almost a century. Paradoxically, there was no justification for this view at this time. The Maritimes had done well from Macdonald’s protectionist National Policy: of the twenty-three cotton mills across the country, eight were down east, as were both of the nation’s steel mills and six of its twelve rolling mills. What had changed was that the golden age of the sailing ship was over: between 1864 and 1887, Nova Scotia’s annual output of wooden ships shrank from 73,000 tons to 14,000. And about this, no one could do anything.

The real cause of the letdown was psychological. As an 1886 editorial in the Halifax Morning Chronicle put it, “The Upper Canadian comes here to sell, but he buys nothing but his hotel fare.… [He] generally conveys the impression that in his own estimation he is a very superior being.” The journalist concluded that “fusion” of Upper Canada and the Maritimes was “absolutely impossible.”

There was truth in this argument. Although Canada had acquired some of the physical attributes of a nation-state, such as a transnational railway, scarcely any national feeling existed. Goldwin Smith understood why: “To make a nation there must be a common life, common sentiments, common aims and common hopes,” and he could see “none” of these qualities in Canada. Some commonalities did exist. The nation had filled itself out, not only from sea to sea, but, by the addition of Britain’s Arctic territories, also now encompassing everything between the forty-ninth parallel and the Pole. It had a national capital with Parliament as its centrepiece, and the distinctive North-West Mounted Police. There was also the Conservative Party—perhaps the most “national” government Canada has ever had, certainly so over so long a span, with strong support in every region from east to west and among both French and English. And there was Macdonald himself—the founding father turned guardian of a troubled infant. But that was about it.

The principal attribute Canadians had in common was that they were anti-American, and that most people were immensely proud of being British. They had little sense of being Canadian, though. A Nova Scotia MP, A.G. Jones, summed it up in a single phrase: “I am a Canadian by an Act of Parliament.” It was a fact, thus, but not a feeling.

Because the times were bad, Canadians from the mid-1880s on turned increasingly inwards. Local concerns took precedence over the national structures Macdonald had built. Pan-Canadianism, in the form of bilingualism in Manitoba, would soon be challenged directly, Orangemen labelling the province “a second Quebec.” The same fate awaited the protectionist National Policy; the new industries it had created were now taken for granted while being blamed for increasing consumers’ costs. The transcontinental railway was criticized almost as soon as built, as westerners pushed their politicians to charter independent railway companies to take their grain to southern markets. Most radical of all, calls were now being made for free trade (reciprocity) with the United States, even for an outright economic union despite its political risks. Simultaneously, there were rising demands for “provincial rights,” not only in Ontario where they began but across the country.

The anonymous poet Troubadour was exaggerating when he wrote to Macdonald that “poor old Canada now sinks, back into her old time grave.” Still, in contrast to the United States, Canada was clearly becoming a state that was failing its people. Nothing magnified the mood of defeatism more than the constant exodus of its people—a loss of population comparable only to Ireland’s during the Great Famine.*

An article by Goldwin Smith captured the circumstances Macdonald had to contend with at this time, even if published a few years earlier. On April 10, 1884, Smith had written, “The task of his political life has been to hold together a set of elements, national, religious, sectional and personal as motley as the component patches of any ‘crazy quilt,’ and actuated each of them by paramount regard for their own interests.… It is more than doubtful that anyone could have done better.… Let it be written on his tomb, that he held out for the country against the blackmailers until the second bell had rung.” Macdonald would respond to the threat posed by free trade and economic union in his last election, in 1891. His immediate task was to deal with the deep internal divisions arising out of language rights and provincial rights. About the scale of the challenge, he had no doubts: “The present is a grave crisis in the political history of Canada,” he wrote a friend in mid-1887.

Since gaining the Quebec premiership at the start of 1887, Honoré Mercier had performed exceptionally well. He had immediately ordered reviews of the government’s finances and administrative machinery, then had followed up with measures to establish industrial schools for workers and to modernize the road system. He also undertook one daring initiative: he announced he would host a conference of the premiers to consider “their financial and other relations.”

Macdonald’s response was consistently negative. When Mercier wrote to ask for a “confidential interview on the subject,” Macdonald offered only an “official” meeting. When Mercier declined this, Macdonald refused to attend the conference. To further minimize the gathering’s importance, he persuaded the Conservative premiers of British Columbia and Prince Edward Island to send their regrets. This enabled him to dismiss the conclave as “a Grit caucus,” even though one Conservative premier, Manitoba’s John Norquay, took part. As weakened the gathering further, the federal Liberals, uneasy about their long-standing opposition to “better terms,” stayed silent about the whole affair.

By outward appearances, the conference went well. Five premiers got together for a week in October 1887 and, with Oliver Mowat in the chair, approved all but one of twenty-four resolutions, ranging from demands that Ottawa cease disallowing provincial legislation, to Senate reform, to better financial terms. These accomplishments were illusory. Macdonald ignored the recommendations on the grounds he had played no part in concocting them. Soon after, they all vanished into the archives. Nevertheless, the event was important. For the first time, provincial premiers had been able to get together to discuss their grievances. Having done it once, they could do it again.

Further, a coherent intellectual argument had been advanced that the provinces were in effect co-governors of the country together with the federal government. Its source was a series of essays titled “Letters upon the Interpretation of the Federal Constitution,” written by T.J.J. Loranger, a leading Quebec Liberal lawyer, and published in Quebec City’s Morning Chronicle in 1884. Loranger advanced the argument that Confederation had been a “compact,” or treaty, among the provinces, rather than the creation of a new national government with the provinces as its subsidiaries. The provinces were the components of Confederation, he argued, and they had created the federal government to deal with certain common interests.

In itself, that notion is hard to credit; no one involved in the Confederation negotiations ever expressed any such intent, the British government included. Ontario and Quebec hadn’t existed before Confederation; even if they had, neither they nor the newcomers, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, because just colonies, possessed the authority to sign a treaty with anyone. This was why Confederation had come into existence by an act of the British Parliament. Nevertheless, Loranger’s essays imparted credibility to an idea now taking hold—that Canada had to be a highly decentralized confederation, a development already under way as a result of the constitutional decisions of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. Macdonald’s view of Canada was rapidly becoming out of date.

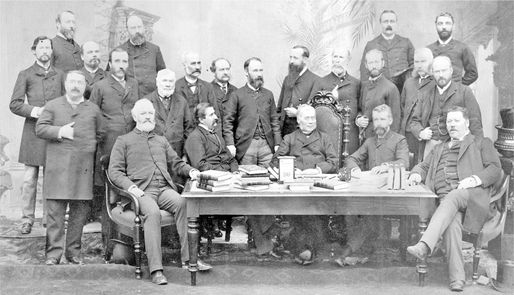

In 1887, Quebec Premier Honoré Mercier, backed by Ontario’s Oliver Mowat, convened the first-ever gathering of provincial premiers. Mowat sits in the centre with Mercier to his left and Nova Scotia’s W.S. Fielding to his right; farther right is Manitoba’s John Norquaym and on the extreme left is the tallest of them all, New Brunswick’s Andrew Blair. They agreed that Ottawa should give them more money and more autonomy. Macdonald paid not the least attention. (photo credit 33.1)

Macdonald began to adjust himself to the new order. For some time now, his most bitter intergovernmental battles had been not with Ontario but with Manitoba. Macdonald had disallowed far more legislation emanating from that small province than from any other—this was why Norquay broke party ranks to attend Mercier’s conference.

Distinctive because he was a Métis, and of imposing size (six foot four and three hundred pounds), Norquay was the right man in the right place when he became Manitoba’s premier in 1879.* As a moderate, he did as well as anyone could have done in minimizing conflicts between all the disparate groups—Métis and whites, French and English, old and new settlers. His connection with Macdonald enabled him repeatedly to secure “better terms,” including increases in Manitoba’s original size.

Yet the ground was shifting under Norquay’s feet too. The ever-increasing English majority—90 per cent by the end of the 1880s—made language tensions inevitable. Far fewer immigrants arrived than had been hoped for; the techniques of dry-land farming took a long time to master; and the Long Depression had sharply reduced the selling price of grain. Together, these factors catalyzed a new political force—an amalgam of regional alienation and populism. The Manitoba Free Press caught its temper in an editorial on August 24, 1887: “For the hideous robbery to which the people are subjected by the extortionate railway rates, for the misfortunes of the farmers, and for the blight from which the prospects of this great and glorious portion of God’s country are suffering so terribly, Sir John Macdonald and his ministers are alone to blame.”

In fact, the principal reason life on the prairies was difficult then was because the flatlands, far from markets and with a severe climate, were a hard place to make a living. Yet there was more than paranoia to the conspiracy theory. The question whether national interests or local interests should have precedence has gone on to become the essence of Canada’s never-ending tug of war between the federal and provincial governments. In its first clear expression, in Manitoba in the late 1880s, the issue was easy to grasp—whether the CPR should exercise monopoly power throughout the West, or whether local interests should be accommodated by allowing competing local lines to be built, thereby benefiting prairie farmers but at the cost of draining traffic away from the national company and central Canada. As to how these could be resolved, Charles Tupper put it bluntly: “Are the interests of Manitoba and the North-West to be sacrificed to the interests of Canada? I say, if it is necessary, yes.”

As soon as the CPR line across the prairies was finished, agitation began for local lines to be built. Time and again, Macdonald disallowed legislation for the competing lines—four in one year alone. The public pressure on him was relentless. The Edmonton Bulletin came up with a splendid bit of invective: “The sun rises in Halifax, shines all day straight over Montreal and Ottawa, and sets in Toronto.”

Eventually, Norquay chartered a line southwards from Winnipeg, even though it would run between two CPR lines. Macdonald successfully pressured the lieutenant-governor of Manitoba to set aside the legislation. Norquay, just back from the premiers’ meeting, responded by staging a sod-turning ceremony. Macdonald then stalled the start of construction by passing word to American and Canadian bankers that Ottawa didn’t want the project to proceed. On a trip to New York to raise money for his line, Norquay seems to have had a breakdown, precipitated by rumours that he had been involved in financial irregularities. By the end of 1887, he was out of office.

In the short term, Macdonald appeared to have won. Yet he accepted that he could not forever deny public opinion. When Norquay’s successor, the Liberal Thomas Greenway, came to Ottawa for negotiations, Macdonald advised him he would not disallow any new railway legislation. It all ended badly: the resulting local line was bought up by the U.S. Northern Pacific Railway and its rates quickly rose to match those of the CPR. Anyway, CPR president George Stephen had by now concluded that the monopoly wasn’t worth the trouble it caused, because the company could buy up many of the new lines cheaply while getting paid handsomely by Ottawa for agreeing to cancel Clause 15, which had granted the monopoly to the CPR.

For the first time, however, provincial rights had won, and this had been achieved not because of decisions made by distant British judges, but because of the force of local public opinion. The West had made its first contribution to the national debate.

The West’s second national intervention would be a good deal less constructive. The target of populist anger now became the iniquity of the East, most particularly Macdonald, in imposing a requirement for bilingualism on the West, even though its population was overwhelmingly English-speaking and becoming ever more so.

Although all the predictable epithets of sectarian extremism—“Rome-worshipping Papists” and “Orange fanatics”—would be hurled across the Ottawa River in the late 1880s, the force dividing the country was not religion but rather race (or, in today’s terminology, ethnicity). Religion certainly mattered: French Canadians were overwhelmingly Catholic and of the right-wing ultramontane persuasion, while English Canadians were overwhelmingly Protestant, the exceptions of course being Irish Catholics. The sectarian war that now broke out, however, was far less about religious matters such as separate schools than about language.

The person who understood this distinction most clearly was D’Alton McCarthy, the man who did the most to magnify the divisions between the two sides. Although a member of the elite, and an exceptional orator, he possessed an uncommon understanding of popular opinion, which he maintained by always remaining an active farmer. He was flawed, though, by a fascination with extremism: in the shrewd assessment of historian J.R. Miller, he “perhaps preferred preaching to the exercise of power.” As a result, his once highly promising political career would peter out.* McCarthy emigrated from Ireland as a child with his father and later did exceptionally well as a corporate lawyer.* An indulgent father and a celebrated host, he yet could also, as one newspaper put it, be “as cold-blooded as an executioner.” While his comments about French Canadians were often brutal, he was never a member of the Orange Order, and at his father’s funeral refused to allow Orangemen to pay their respects unless they removed their regalia.

McCarthy began his lonely path with a speech in Barrie during the 1887 election, in which he declared, provocatively but presciently, “It is not religion which is at the bottom of this matter but race feeling.… Do they mix with us, assimilate with us, intermarry with us? Do they read our literature or learn our laws?” To McCarthy, it was the Frenchness of French Canadians, not their Catholicism, which constituted what he called “the great danger to Confederation.” As he saw it, so long as Canada remained both French and English, it could never become a true nation-state in the manner of Britain or the United States or France. McCarthy never challenged the constitutional protections for the French language in Quebec, but he did all he could to suppress the use of French outside the province. The protests he stirred up would lead to the abolition of bilingualism in Manitoba and the North-West, and later in Ontario. McCarthy thus played a critical part in creating a Canada that would no longer be Macdonald’s Canada—still less Pierre Trudeau’s Canada.

The sectarian war began as a confrontation over that quintessentially Canadian religious dispute—the treatment of Jesuits. One of the reforms Honoré Mercier initiated as premier concerned a long-standing dispute over what were known as the Jesuits’ Estates. The disputed lands had once been owned by the Jesuits but had reverted to the Crown when the order was dissolved by the Pope in 1773. When the Jesuits were later reprieved, in 1814, they returned to the province. The distribution of these lands among claimants ranging from Laval University to the Jesuits themselves became an issue of financial consequence and great political moment.

Mercier’s solution, announced in 1889, was eminently sensible. Laval and the Jesuits would both get shares, as would other Catholic institutions and Quebec’s Protestants. As a demagogue, however, Mercier understood the value of having an enemy of the right kind. His act was just one page long, but preceding it was a fifteen-page preamble that included all his correspondence on the matter with the Vatican, including the statement that “the Holy Father reserves to himself the right of settling the question.” In the Quebec legislature, this bill, so deferential to the Pope, delighted the ultramontanes and passed easily. The Ontario press, though, took note that the Pope, a foreign potentate, had been asked to decide a strictly domestic Canadian affair. The Orange Sentinel demanded that Macdonald’s government “apply the veto power” to Mercier’s bill and promised that such action would receive “the hearty endorsement and commendation of all who love their country.”

The scene was set for a confrontation between Ontario and Quebec, with Macdonald as the certain loser. Without Ontario’s Orange vote, he could never win a majority in the province. Yet if he disallowed Mercier’s law, his bleu supporters would rebel and he would lose Quebec. That fall, Mercier came to Ottawa to see Macdonald, and during a walk together he asked Macdonald whether he intended to disallow his Jesuits’ Estates legislation. In Joseph Pope’s recollection, “Suddenly the old man unbent, his eyes brightened, his features grew mobile as he half looked back over his shoulder, and said in a stage whisper, ‘Do you take me for a damn fool?’ ” No doubt Mercier was deeply disappointed—to have provincial legislation vetoed by the same man who had executed Riel would have been the ultimate political gift. In mid-January 1889, Macdonald leaked word that the government had decided that “the subject-matter of the Act is one of provincial concern only.” There was to be no disallowance.

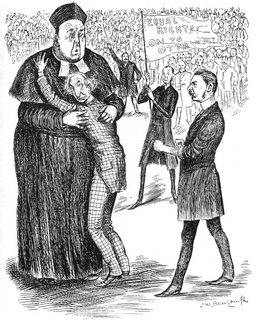

Ontario newspapers, including mainstream ones such as the Globe, now denounced the government for failing to veto Mercier’s legislation, on such grounds as that the Jesuits were “a disloyal society.” By March, mass meetings in Toronto had led to the creation of an Equal Rights Association dedicated to suppressing the rights of French Canadians. Anger at Quebec extended far beyond the hardline Orange Order. In the magazine Grip, the satirist Bengough, so often a progressive, as on votes for women and fair treatment for Aboriginals, wrote that “the French element” would prevent the development of the Canadian nation, because they were out to “transform this Dominion into a mediaeval Province of Popedom.”

Grip caught the mood of sectarian hatred and fear and suspicion with its cartoon of Macdonald clinging to a Quebec cleric while the errant Conservative, D’Alton McCarthy, advances on him at the head of a throng of honest, respectable Ontario Protestants.

Macdonald responded with irritation modulated by anxiety. He told his friend Judge James Robert Gowan, “The demon of religious animosity which I had hoped had been buried in the grave of George Brown has been revived”; the consequence might be “dragon’s teeth [which] I fear may grow into armed men.” He warned Charles Tupper that although “the unwholesome agitation” was confined to Ontario and Quebec, “the drum ecclesiastic is now being beaten so loudly that the sound may reach the other provinces.” By early 1890, Macdonald had to admit there was “fanaticism both in the East and the West.” This transformation was McCarthy’s doing.

Although his relations with McCarthy had become severely strained, Macdonald did all he could to avoid an outright break. Early in 1889, a Conservative MP allied to McCarthy moved a resolution in the Commons calling on the government to disallow Mercier’s Jesuits’ Estates Act. The measure was defeated overwhelmingly, with only thirteen dissident Conservatives voting for it. Macdonald later dubbed them “the Devil’s dozen.” He didn’t speak during the debate, but allowed Justice Minister John Thompson to respond with a brilliant and crushing analysis of McCarthy’s long and sometimes eloquent speech. Afterwards, Macdonald worried that Thompson had done too well and perhaps incensed the humiliated McCarthy. He recalled the advice Elizabeth I gave to Walter Raleigh: “Anger makes men witty, but it keeps them poor.” Instead, the tactic Macdonald settled on was to avoid criticizing the many Conservatives who supported the Equal Rights Association on the grounds that, if admonished, they would find it hard to later change their minds.

In early April, Macdonald wrote a long letter to McCarthy which has been lost, but McCarthy’s reply to it, of April 17, conveys the state of their relationship. “Our views are so wide apart,” he wrote, “that I do not see how they can be reconciled.” To McCarthy, the fundamental national question was “not whether we are to be annexed or to remain a part of the British Empire, but whether this country is to be English or French.” To Macdonald, the answer was that Canada had to be both.

McCarthy made his public break with Macdonald on July 12, 1889—the “Glorious Twelfth” to all Orangemen. Provoked by a fiery speech delivered by Mercier on Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, Quebec’s June 24 holiday, McCarthy gave a talk in the Ontario hamlet of Stayner in which he referred to the French as a “bastard nationality” that threatened Confederation. He called for the abolition of French-language schools in Ontario and urged that bilingualism be ended in the North-West. If the “ballot box” did not provide a solution for this generation, he proclaimed, “bayonets will supply it in the next.”

McCarthy now embarked on a tour of the West, where he gave speeches in Portage la Prairie and in Calgary. Neither was especially inflammatory, dealing principally with the need for a strong central government, yet both had a galvanic effect on the race issue. The reason was that, at Portage, he was followed by Manitoba’s attorney general, Joseph Martin, who not only dismissed French as “a foreign language” but declared that the government would abolish separate schools and cease printing government documents in French. This speech was so popular—among its supporters was the prominent Winnipeg lawyer Hugh John Macdonald—that Premier Greenway, even though a moderate, was soon obliged to confirm his attorney general’s pronouncements. The next year, the government introduced legislation to end public funding of separate schools and of publishing the official Gazette in French. The “fanaticism” Macdonald had feared was out of control.

So far, Macdonald had said as little as possible, conserving his strength for a critical moment. But he could no longer linger on the sidelines. In January 1890, McCarthy moved a private member’s bill in the Commons to cancel the guarantees in the North-West Territories Act for the use of French in the legislature and in the courts. His reasoning was that “in the interests of national unity in the Dominion, there should be community of language among the people of Canada.” Historian Peter Waite has described what followed as “one of the great debates in the history of the Canadian Parliament … [about] what Canada was and what it should be.” The finest single speech came from Wilfrid Laurier, who argued for calm, reason and respect.* McCarthy’s effort was also one of his best, moderate in its language yet woundingly divisive in its consequences. Macdonald’s speech, while not one of his best, was one of his most memorable, because it turned out to be his final appeal for harmony between the races. And what he said would become the source of one of the greatest tributes ever paid to him.

Macdonald spoke twice, always in conciliatory terms, trying to edge those on the extremes back towards the centre. On February 17, right after Laurier, he began by saying that any attempt to “oppress the [French] language or to render it inferior would be impossible if it were tried and it would be foolish and wicked if it were possible.” It had often been said, he continued, “that this is a conquered country.” Even if true, this meant nothing: “Whether it was conquered or conceded, we have a constitution now under which all British subjects are in a position of absolute equality, having equal rights of every kind—of language, of religion, of property and of person.” The truth was, he continued, “there is no paramount race in this country: we are all British subjects, and those who are not English are none the less British subjects on that account.” As for the bill’s objective of changing the language rules in the North-West, “whether the people occupy a Territory or occupy a Province, if they want to use the French language they should be allowed to use it, and if they want to use the English language they should be allowed to use it, and it should be left to themselves.”

Three days later, Macdonald intervened again. By this time Thompson had put forward a compromise proposal based on the recognition that the North-West Legislative Assembly did have the right to decide in which languages or language its own proceedings should be published. All other protections for French, though, should continue. In making his argument that this compromise should be accepted, Macdonald asked MPs to compare themselves to the Canadian parliamentarians who had come before them. He recalled that back in 1793, soon after the Province of Upper Canada had been created, its legislature had met for the first time in Newark (today, Niagara-on-the-Lake). The members of this infant legislature, all of them “Englishmen,” had discussed the fact that, in the new province’s extreme southwest, there were some small settlements of “Frenchmen” in present-day Essex County.

That old pioneering legislature had then passed an order that Macdonald now read out: “That such acts as have been already passed, or may hereafter pass the Legislature of this Province, be translated into the French language for the benefit of the inhabitants of the western district of this Province and other French settlers who may come to reside.” At this point, Macdonald put a question to his audience: “Are we, one hundred years later, going to be less liberal to our French-Canadian fellow-subjects than were the few Englishmen, United Empire Loyalists, who settled Ontario?” When the vote was taken, McCarthy’s bill was defeated overwhelmingly.

None of this agitation had any immediate effect, but in 1892 the North-West Legislative Assembly would abolish the official use of French throughout the region. In Manitoba, provincial legislation was enacted to limit the public funding of separate schools and was appealed all the way up to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, but upheld by that body. The issue would be settled in 1896 by a compromise negotiated between Laurier and Premier Greenway that limited instruction in French to schools where a sufficient number of students required it. Later, a similar restriction was implemented in Ontario. As Laurier had to explain to his own Quebecers, “There was no other solution for this question … [because of] the necessity for the people of Quebec to maintain inviolate the principle of local autonomy.” Implicitly, Laurier was accepting that Canada was no longer Macdonald’s Canada but McCarthy’s—and so in the form in which it would remain until the Official Languages Act of 1969.

Macdonald had said his last words about the relationship between the two founding European races. The final word about the goal of harmony between them, which he had tried for so long to maintain, had yet to be said, however. By the 1920s, it had become the practice for a Quebec MP to sponsor each year a private member’s bill to give French-Canadian civil servants a bonus for the translation work they did for unilingual colleagues. None of these bills ever passed, but they did keep alive the idea of bilingualism.

In 1927 bilingualism’s greatest champion of the time joined the debate. He was Henri Bourassa, the founder of Le Devoir. Bourassa intervened to say that, rather than try to justify the motion by quoting the complaints of French Canadians, he would instead cite the words of “the one man who best understood and to a large extent best applied the spirit of confederation.” That person was Sir John A. Macdonald. Bourassa then recounted the history lesson Macdonald had given the parliamentarians of his day about the generosity shown by their ancestors. The bill still went nowhere. But a third of a century after Macdonald’s death, these two uncommon Canadians reached out and shook each other’s hand.

* At the time Laurier became leader, most Liberals and political observers regarded him as only a stopgap because he was so inexperienced. Among the few to detect his potential when he was young and callow was Macdonald.

* Fielding would have a most successful career. He was premier for a decade, then joined Laurier’s government as minister of finance and held the post for a record fifteen years. In 1919, he ran for the Liberal leadership, losing to Mackenzie King by just thirty-eight votes.

* About one million Canadians left during the last decades of the nineteenth century. Ireland’s loss during the Great Famine was a million and a half, but from an original population of eight million, close to double that of Canada. Ireland, though, also lost a million people by outright starvation.

* Norquay took great pride in his ancestry, wearing both a suit and moccasins in the legislature.

* A major source for the material in this chapter is Miller’s book Equal Rights: The Jesuits’ Estates Act Controversy as well as his articles on the subject in the Canadian Historical Review and the Journal of Canadian Studies.

* McCarthy was so able a lawyer that he would be offered the prime portfolio of minister of justice by both Macdonald and, much later, Laurier.

* One far-sighted observation by Laurier was that English “is today, and must be for several generations, perhaps several centuries, the commanding language of the world.”