He believed that there was room on the continent of America for at least two nations, and he was determined that Canada should be a nation.

George Monro Grant, writing about Macdonald

Macdonald faded away quietly, much as old soldiers are said to do. His exceptional constitution still allowed him one last burst of energy, or at least a show of it. The election over, he stayed at Earnscliffe through the rest of March and well into April, much of the time resting in bed but also receiving many more visitors than Lady Macdonald would have wished, and churning out letters on such urgent government matters as whether the baggage-master at Hampton merited an increase in pay to $1.50 a day. In Macdonald’s opinion, he did not.

The approach of spring and the opening of the first session of the new Parliament brought Macdonald into the open with a small lift to his step, even though he wearied quickly. For the opening occasion in the House he knew so well, he wore his signature outfit of a frock coat, soft grey trousers, a stovepipe hat and a large and floppy red necktie. Proudly, he and Hugh John signed their names one after the other in the register. During the Throne Speech debate, Macdonald spoke briefly but deftly, teasing Laurier over his electoral disappointment: “J’y suis, j’y reste. We are going to stay here and it will take more than the power of the Hon. Gentleman with all the phalanx behind him, to disturb us or to shove us from our pedestal.” One reporter wrote of him, “His eye was clear, his step elastic.” Hugh John advised Professor Williamson in Kingston that his father was “now very much better.”

In fact, he had made his last bow on the stage. On May 12, Macdonald went to his parliamentary office to discuss with Governor General Stanley the possibility of an Anglo-American confrontation in the Bering Strait because of a Canada-U.S. dispute over seal-hunting rights. While explaining the matter, he found he could no longer speak properly. He asked Joseph Pope to bring in John Thompson. Once Thompson arrived, Macdonald, looking highly embarrassed and utterly weary, asked him to brief the governor general. At that point, Stanley noticed that Macdonald’s mouth was drawn and twisted. As soon as Stanley had left, Macdonald turned to Pope, a note of fear sounding clearly through his thickened voice, and told him, “I am afraid of paralysis. Both my parents died of it and I seem to feel it creeping over me.” Macdonald’s fear was not that the next stroke might fell him, but that it would not. As he explained to one of his doctors, “I hope to God I don’t hang on like Mackenzie,” the former Liberal leader, who still lingered in the House, forever shaking and almost never speaking. Because this stroke was a mild one, Macdonald managed to conceal from Agnes what had happened.

That evening, all the symptoms of his stroke eased, and his speech returned to near normal. His doctor urged him to take a complete rest away from Ottawa. Macdonald refused to leave while Parliament was in session; he did agree to rest as much as possible, but insisted he had to be present at cabinet meetings and debates in Parliament. Back in the chamber again, his spirits revived and he sat listening to the debates, sometimes cheering on a Conservative MP or discomfiting a Liberal with some quip.

Friday May 22 was a soft, warm day, and Macdonald spent it on the Hill. In Thompson’s words to Annie, he was “very well and bright again.” Early in the evening, Macdonald went down to the basement for a shave by the parliamentary barber, Napoleon Audette. While there, he studied a framed engraving of the Legislature members of 1855, a decade after he had first entered politics. He called out their names—Morin, Augers, Caron, Mackay, Dunkin, Short, Meredith, LaFontaine, Drummond—and told Audette, “All gone, all gone.” Back in the chamber, Mackenzie Bowell, one of his ministers, teased Macdonald into agreeing that it was time for two oldsters like them to be “at home in bed.” Macdonald responded, “I will go. Good-night.” These were the last words he ever spoke in the House of Commons.

For several days, he continued to maintain much of his regular schedule, insisting, over Agnes’s protests, that they have their usual Saturday dinner for Conservative MPs and staying up until the guests had left. That night, Macdonald woke up at 2:30 a.m. to discover Agnes bending over him. She had come into his bedroom in response to his incoherent shouts, and he admitted to her he had lost all feeling in his left leg. The next morning, Macdonald managed to talk to Thompson about government business in slow, painfully prolonged whispers. His leg had recovered.

Word of his illness began to circulate beyond his inner circle, and his doctors issued regular bulletins on his condition. On Thursday May 28, they reported he had experienced “a return of his attack of physical and nervous prostration” for which they had prescribed “entire freedom from public duties.”

One day later, Macdonald suffered a third stroke. It left all his right side paralyzed and all but ended his ability to speak, although he still could reply to carefully enunciated questions from visitors—Agnes, Hugh John, Pope or one of the doctors—by squeezing their hands. Lord Stanley later described to the Queen the unflagging care Lady Macdonald provided her dying husband: “She never left his side, always thinking he would be able to say some last words to her, but they never came and it was only by the pressure of his hand that she knew that he knew she was at his side.”

By now, word of the seriousness of Macdonald’s condition had spread out across the entire country. All the barges on the Ottawa River silenced their whistles as they passed Earnscliffe, and horse-drawn carriages along Sussex Drive no longer used their bells. Outside the house, reporters stood on guard day and night, and a special telegraph wire was set up to flash the news outwards. The doctors continued their bulletins, although not making public the diagnosis of one senior specialist, James Grant: “Hemorrhage on the brain. Condition hopeless.”

On June 1, the weather turned hot. The heavy curtains in his bedroom were pulled tight shut. Sometimes, Macdonald would swallow a glass of milk or beef tea in small sips, and even take a little champagne. Everyone spoke in whispers. His grandson, Jack, Hugh John’s son, insisted on seeing him and prattled away at his bedside, unable to understand why his grandfather never answered his questions. Macdonald’s own Mary was then brought into the bedroom and managed by some intuitive skill to convince Jack to remain quiet. Their very presence, though, seemed to revive him.

At 6:30 a.m. on June 6, 1891, the doctors issued a bulletin that Macdonald was “still alive.” Their next bulletin, at 10 a.m., reported his death, and the news flashed by telegram across the country. (photo credit 35.1)

Meanwhile, government ministers were frantically exchanging gossip and opinions about who might succeed him. Would it be Mackenzie Bowell, J.J. Abbott, Charles Tupper or Hector-Louis Langevin, the most senior cabinet member but one mired in a scandal? Or should it be John Thompson, by far the ablest man, but politically flawed because he had converted to Catholicism? Clearly, Macdonald either hadn’t made up his mind who should succeed him, or could no longer tell his ministers what he wanted done.

The doctors’ bulletins described a patient fighting to the end. On Thursday June 4, they reported: “Sir John A. Macdonald passed a fairly comfortable night.… His cerebral symptoms are slightly improved.” The next day, the tone was sombre: “We find Sir John Macdonald altogether in a somewhat alarming state.… In our opinion, his powers of life are steadily waning.”

Shortly after 10 a.m. on Saturday June 6, 1891, Joseph Pope emerged from the door at Earnscliffe with a message for the crowd of reporters waiting in the grounds outside. “Gentlemen,” he said, “Sir John Macdonald is dead.” He then pinned the doctors’ last bulletin onto the gate.

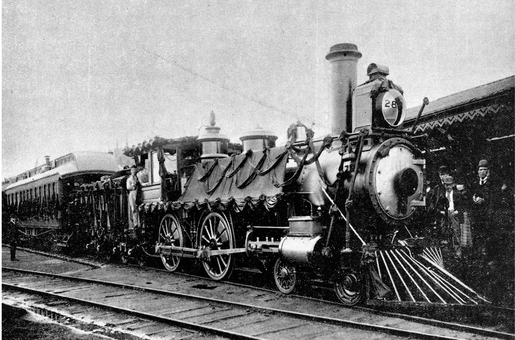

All the churches in Ottawa began to toll their bells. As the news spread out by telegraph and telephone, through towns and hamlets connected by railway lines, along the coasts by calls shouted from one fishing boat to another, and out in the countryside by solitary riders passing farmers in the fields, church bells everywhere began to toll—from Cape Breton to Vancouver Island, all the way across the impossible magnitude of the country Macdonald had created.

As always, Laurier was the most eloquent. In the Commons two days later, he said, “The place of Sir John Macdonald in this country was so large and so absorbing that it is almost impossible to conceive that the political life of this country, the fate of this country, can continue without him … as if indeed one of the institutions of the land had given way.” Before him, Langevin had tried to speak but could only say, “My heart is full of tears; I cannot proceed.” Although a coincidence, it was appropriate that both of the official eulogies for Macdonald should have been given by French Canadians.

Afterwards, others said what Langevin had tried to say. Thompson told the Montreal Daily Star, “He was the founder and father of the country.… There is not one of us who had not lost our heart to him.” Goldwin Smith wrote, “He combined lifelong experience with consummate tact.… He had singular attractiveness of manner with a playful wit. He had great social versatility.… He was a thorough man of the world, with nothing about him narrow or fanatical.” No one better captured John A. Macdonald’s essence than did his constant critic J.W. Bengough, at Grip magazine: “He was no harsh, self-righteous Pharisee.”

Not everyone thought this way. Sir Daniel Wilson, president of the University of Toronto, declared that Macdonald had been a “clever, most unprincipled party leader [who] developed a system of political corruption that has demoralized the country. Its evils will long survive him.”* Years later, Richard Cartwright, by then Laurier’s minister of trade and industry, declared that no statue of Macdonald should go up on Parliament Hill unless its inscription included “Canadian Pacific Scandal.”

The response of ordinary Canadians was utterly different. The Week admitted that its erudite commentaries had completely missed the most important part of Macdonald’s political life: “It is now seen that the dying Premier had a hold not only upon the popular intellect and imagination but upon the popular heart, to a degree which few, probably, had believed or imagined.… There must have been in the man, as distinct from the politician, depths of genuine feeling and sympathy, of the existence of which many a week ago would have been incredulous.” John Willison, in his Reminiscences, said it more directly: “It was no common man who so touched a nation’s heart.”

On the Monday, the day of Langevin’s and Laurier’s eulogies, the Commons chamber was draped in black, similarly Macdonald’s seat, with a spray of white flowers on his desk. He lay in state in the Senate chamber for two and a half days, with the public allowed to come in only for the last day. During that time, more than twenty thousand people—as many as Ottawa’s total population—walked past his coffin. After the funeral service at St. Alban’s Church, his body was taken to the railway station to make its last journey to Kingston. The route took him past all the familiar towns and hamlets—Stittsville, Carleton Place, Perth, Sharbot Lake, Harrowsmith—with crowds gathered everywhere along the line, all the men bare-headed. At Kingston, he lay in state in the City Hall, his open casket guarded by military cadets. There, some ten thousand walked past the casket—double the town’s population.

He was buried in Cataraqui Cemetery near to the graves of his mother and father, his sisters and his infant son, John Alexander. Above his grave, the inscription on the simple Latin cross read, “Sir John A. Macdonald, 1815–1891. May he rest in Peace.” The cemetery is close enough to the Toronto—Montreal main line for the whistles of the trains to be heard as they thunder along, some heading westwards by the all-Canadian route, around Lake Superior, across the prairies and over the Rockies, to the end of the line at the edge of the Pacific. One detail of all this ceremony might have caused Macdonald to raise an eyebrow: his casket, of rolled steel painted the colour of rosewood, had been imported from the United States.

After his open casket had lain in state in the Parliament Buildings for two and a half days, a special train carried Macdonald to Kingston past bare-headed throngs standing along the track. After a ceremony, a huge procession accompanied the casket to Cataraqui Cemetery, where he was buried beside his family, beneath a plain stone cross inscribed, “Sir John A. Macdonald, 1815-1891. May he rest in Peace.” (photo credit 35.3)

* Wilson had an exceptionally low opinion of all politicians and had quarrelled with Macdonald over his having been made, in 1888, only a knight bachelor, a lower honour than that granted to politicians.