12

Friendless

THE BIRTH OF A SECOND CHILD on February 3, 1924, irreparably altered the marriage of Buster and Natalie Keaton and signaled the beginning of a slow descent into estrangement. The eight-pound boy, born at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Los Angeles, had no ready name, even though Dutch and Peg Talmadge were present for the event. The convention of naming a newborn by acclamation was established with Jimmy’s arrival two years earlier, but Norma was in Palm Beach with Joe Schenck. “Norma must be consulted,” a news item in the Times confirmed, “and she is three thousand miles away.” There was no mention of the father’s role in the matter.

It was no secret that Peg Talmadge exerted tremendous influence over her three girls, a bond forged in childhood when the family was abandoned by the father, an alcoholic sales rep named Fred, and Peg was forced to take in laundry and boarders and sell cosmetics to make ends meet. The girls attended Erasmus Hall in Brooklyn, and when Norma was fourteen her mother started her out as a photographer’s model. As the shrewd manager of two and a half careers, Peg made them all rich, but she also fostered a mutual dependency that lasted for the rest of her life. When the subject of Natalie was raised, a family friend was clear: “Norma and Constance are as devoted to her as they are to each other, and they all three unite in worshipping their mother.”

Although Natalie did fine work in Our Hospitality, her pregnancy nearly scuttled the film. “Before we finished that picture,” said Buster, “we didn’t dare photograph her in profile. Joe Schenck said, ‘Never use Natalie in another picture. You could break this company.’ ” It was a comment that, were it to get around, would have turned Peg Talmadge’s unruly head of salt-and-pepper hair to bright white. Motherhood was the one distinction Nate had over her star siblings. What if either Norma or Dutch were to decide that they wanted kids too? Particularly Norma, whom exhibitors that year voted the nation’s top female star by a wide margin? A couple of careless pregnancies could wreck the family business Peg had worked so hard to build.

Natalie Keaton cradles Robert Talmadge Keaton as Buster looks on. Little Joseph, age two, stares straight into the camera.

“By this time,” said Buster, “having got two boys in our first three years, frankly, it looked as if my work was done. I was ruled ineligible. Lost my amateur standing. They said I was a pro. I was moved into my own bedroom.”

Two children—the second was dubbed Robert Talmadge Keaton—cemented Natalie’s status as a homemaker. “I like to cook, to sew, to keep house,” she told Julia Harpman of the New York Daily News. “Studio life is appealing enough, but somehow I always felt that, as a woman, true happiness for me could be found only in wifehood. When ‘Winks’—that’s baby Joseph—came, my dream of happiness was fulfilled. Motherhood is the greatest career a woman can have. I know it is trite to say that, but it is so true and there are so many women on the screen who, I am sure, would like to admit it but haven’t the courage to sacrifice for motherhood all they have struggled and won in public acclaim.”

Despite such pronouncements, Natalie’s dream of happiness wasn’t all that fulfilled. Buster thought the Ardmore house wonderful, but it wasn’t even a year before a move to Hancock Park was mandated. This time it was a fourteen-room mansion on Muirfield Road that cost $75,000. “The Muirfield place was bigger, better, fancier—hell, why argue? We bought it and began housewarming. That meant—for me anyway—two o’clock to bed and up at six, grab breakfast, and off to work.” And their bedroom suites, he found, were at opposite ends of the building. Buster knew the source of the trouble and addressed his mother-in-law directly: “I’m just going to let you know right now I am not going to take a mistress and support her, or do anything like that. I will not be spending any money on women and throwing my money around. But if I can’t get it at home, I’m going to get it somewhere. And there’s a lot of free stuff out there. If you forbid your daughter to sleep with me, I’ll go outside and get it.”

Keeping Nat happy had always been the prime motivator in each of the moves, even though they had been profitable enough to enable Buster to buy his mother a comfortable two-bedroom home in the mid-Wilshire district. That same year, Myra sold off all but two of the remaining Keaton properties in Muskegon (having disposed of Jingles Jungle in 1923) and found time to visit Frank Cutler in Rockdale, Texas—the first time she had reportedly seen her father in more than twenty-five years.

Up to and including The Navigator, all of Buster Keaton’s comedies had been made under the terms of the original five-year contract he signed with the Comique Film Corporation in December 1919. Now, after nineteen two-reelers and four well-received features, it was due to expire on December 31, 1924. Not only had Keaton grown in popularity domestically, but his international profile was second only to Chaplin’s. In Stockholm, Our Hospitality held the screen at the Royal Dramatic Theatre for fifteen weeks, supported by a Swedish version of Buster who walked the streets of the city. “He carried no back banner, and there were no cards on the gripsack,” Moving Picture World reported. “Everyone knew who he was supposed to be, and the billboards gave the details, if any were needed.”

Harold Lloyd was the star for whom British exhibitors were willing to pay the highest price, but it was Keaton who played twenty-one weeks in Belgium, making more money for the distributor on a percentage basis than the company’s entire line of films the previous season. And in Paris, Our Hospitality, retitled Laws of Hospitality, broke all records at the Madeleine, where it earned 11,500 francs on Armistice Day alone.

“It is a singular fact,” said Billboard, “that this Keaton feature has been playing in Europe with the greatest success of any American motion picture, not barring even the elaborate spectacles. It has broken records throughout the Scandinavian countries, in Stockholm, Christiania, Copenhagen, and other centers there.”

The new contract, signed September 9, 1924, and set to take effect upon release of The Navigator, called for “six motion picture feature photoplays of not less than forty-five hundred nor more than nine-thousand feet in length.” In terms of compensation, Keaton was to receive $27,000 for each completed feature, payable in installments of $1,000 per week, plus 25 percent of the cumulative net profits. Although not specifically called out in the contract, the Los Angeles Times set the approximate value of the new slate of features at $1,800,000, or roughly $300,000 a picture. At the rate of two releases a year, the pact would remain in effect through the spring of 1928.

Seven Chances was a film Buster Keaton never wanted to make. A Broadway stage hit from 1916, the play’s principal character stands to inherit a fortune of $12 million if he is married by the age of thirty—and he is due to turn thirty the following day. There is no steady girlfriend, not even one on the horizon, and no real inclination to solicit one. Written by Roi Cooper Megrue (It Pays to Advertise), the show drew mixed notices, its undisputed highspot being actor-playwright Frank Craven’s droll performance as Megrue’s hero, a self-confessed woman hater by the name of Jimmie Shannon.

“[It] was not a good story for me,” Keaton explained. “That was bought by someone and sold to Joe Schenck without us knowin’ it. As a rule, Schenck never knew when I was shootin’ or what I was shootin’. He just went to the preview. But somebody sold him this show that was done by Belasco a few years before….And he buys this thing for me and it’s no good for me at all.”

The someone who sold Schenck on the play was a writer-director named Jack McDermott, a “local screwball” in Keaton’s estimation who had started as an actor, made shorts for Fox and Universal, then moved into features. Keaton considered the $25,000 Schenck paid for the property a waste of money—the material was thin, the characters bloodless, the laughs dependent solely upon dialogue. It was, he said, “the type of unbelievable farce I don’t like.” Anxious to lose the thing, Keaton tried interesting Schenck in making it with Syd Chaplin, Charlie’s half brother, a suggestion that went nowhere. The subsequent idea of making the film in color was an act of desperation, with an article in Exhibitors Trade Review noting how Keaton had been “experimenting with the possibilities of color photography for comedy values.”[*1]

Having never meddled before in the making of the Keaton pictures, Schenck’s actions left his star comedian bewildered, for he was also stuck, he learned, with McDermott as his new director. Could Schenck have been responding to the drop in revenues for Sherlock Jr.? Or cost overruns on The Navigator ? Had McDermott sold Joe on the notion of source material with a commercial track record? Something along the lines of The Saphead ? Schenck never offered an explanation, and Keaton, apparently, never asked. For the role of Mary Jones, Jimmie’s girl, Buster wanted Marian Nixon, who was appearing in westerns for Fox, but found that she had been loaned to Universal for a Hoot Gibson picture. Instead, he selected Ruth Dwyer, who was attracting notice in a romantic comedy titled The Reckless Age opposite Reginald Denny.

Filming began on September 16, 1924, the company sharing studio space on the Keaton lot with Roland West’s independent production The Monster starring Lon Chaney. Keaton and McDermott shot the film’s prologue, a courtship exterior stretching over four seasons, in Technicolor, making it the only remnant of the plan to shoot the entire movie that way. Upon learning that he stands to inherit $7 million if he is married by seven o’clock on the evening of his twenty-seventh birthday, Jimmie Shannon races to the home of his longtime girlfriend in a decidedly inventive way—by not driving the car at all.

“I had an automobile, like a Stutz Bearcat roadster. I was in front of [a country club]. Now, it’s a full-figure shot of that automobile and me. I come down, got into the car…I release the emergency brake after starting it, sit back to drive—and I don’t move. The scene changed, and I was in front of a little cottage out in the country. I reach forward, pull on the emergency brake, shut my motor off, and went into the cottage. I come back out after I visit her, get into the automobile, turn it on, sit back there—and I and the automobile never moved—and the scene changed back to the [country club]. Now, that automobile’s got to be exactly the same distance, the same height and everything, to make that work, because the scene overlaps but I don’t….We made sure [it was the] same time of day so the shadows would [be in the same place]. But for that baby we used surveying instruments so that the front part of the car would be the same distance from [the camera], the whole shooting match.”

Keaton proposes to bit player Jean Arthur in Seven Chances (1925). She responds by flashing her wedding ring.

Perplexed, evidently, by the time and care lavished on this seemingly minor transition, Jack McDermott withdrew as director of Seven Chances after completing the first week of filming. “You are the star and producer,” he told Keaton, “and your version will be the one finally used. You are wasting thousands of dollars having me on the picture.” McDermott had come onto the project just a week ahead of production and envisioned a faithful rendering of the play, a farce on the order of Her Temporary Husband, a picture he had made the previous year. Although he had supposedly signed a seven-picture deal with Schenck, McDermott vanished, and Keaton went on to direct the rest of the picture himself. By then, The Navigator was looking like a hit, and Schenck, evidently mollified, backed off.

Jimmie, of course, botches his proposal to Mary, who angrily stalks off. Now he must find somebody else to marry, and fast. Keaton and his writers jettisoned a tedious first act in its entirety, translating Shannon’s increasingly desperate search for a wife into purely visual terms. “When you’ve got spots in there where you can do things in action without dialogue,” he said, “you should take advantage of it….First instructions with the new writers we were getting from Broadway; see, everything with them was based on a joke, funny saying, people shouting. But we’d tell our story, our plot with our characters, and we talk when necessary. But we don’t go out of our way to talk. Let’s see how much material we can get where dialogue is not needed.”

Seven times Jimmie proposes, and seven times he is rejected. (Among the candidates are Doris Deane, Roscoe Arbuckle’s fiancée; actress-dancer Pauline Toler; and Bartine Burkett, Buster’s leading lady from The High Sign.) Finally, Billy Meekin, Jimmie’s business partner (T. Roy Barnes), takes charge. “Meet me at the Broad Street Church at five o’clock,” he tells Jimmie. “I’ll have a bride there if it’s the last act of my life.” What Shannon doesn’t know is that Meekin plans on feeding the story to the Daily News. Come five o’clock, Jimmie is in the front pew of the empty church, a bouquet in hand and two tickets to Niagara Falls in his pocket. Wearily, he dozes off, and the church begins to fill, first a scattering, then an onslaught, women of “all shapes and forms with home-made bridal outfits on, lace curtains, gingham table cloths for veils” spilling out onto the sidewalks.

The play Seven Chances lacked a strong finish, and by turning the story into one clear progression to an inevitable chase—which grew to constitute the entire third act of the picture—Keaton firmly and indelibly moved it from the cloistered realm of the stage to the limitless expanse of the big screen. Shannon awakens to an unruly mob scene, made all the worse when the minister tells the women they are evidently the victims of a practical joker. They turn their ire on Jimmie, who sinks into the crowd and escapes out a side window, droves of menacing brides flooding the streets in hot pursuit. Here Keaton effectively sets in motion a clever reprise of Cops in white lace and heels. The stampeding women trample a football team, commandeer a trolley, invade a scrap yard, flatten a cornfield. Meanwhile, Mary is waiting at her house with Jimmie’s partner and a minister as the clock ticks off the final minutes to the seven o’clock deadline.

When Seven Chances finished on November 29, Keaton thought the picture “fair” and the conclusion weak. “My God,” he said, “we actually hired five hundred women, every shape and every size, and bridal outfits on all of ’em. Well, hell, I can outrun ’em. And even if they catch me, how can you end the picture? Can I marry all of ’em? Not even in Utah. Can I fight ’em? So we’re crippled. Can’t get in any good chase gags, can’t end it with any kind of climax. So we simply decided to fade on the chase.”

The first preview didn’t go well. “I had a bad picture and we knew it, too. And there was nothing we could seem to do about it.”

A church full of eager brides confronts Jimmie Shannon in Seven Chances.

Adjustments were made, a second preview was held. Again, it just didn’t seem to build to anything. But this time, Keaton noticed something interesting in a portion of the chase in which he ran downhill at a good clip. “I went down to the dunes just off the Pacific Ocean out at Los Angeles, and I accidentally dislodged a boulder in coming down. All I had set up for the scene was a camera panning with me as I came over the skyline and was chased down into the valley. But I dislodged this rock, and it in turn dislodged two others, and they chased me down this hill.

“That’s all there was: just three rocks. But the audience at the preview sat up in their seats and expected more. So we went right back and ordered fifteen hundred rocks built, from bowling alley size up to boulders eight feet in diameter. Then we went out to the Ridge Route, which is in the High Sierras, to a mountain steeper than a forty-five-degree angle. A couple of truckloads of men took those rocks up and planted them, and then I went up to the top and came down with the rocks.” Not only did the rocks and boulders give the chase an extra dimension at a critical moment, but they had the added advantage of appearing even more dangerous than the bloodthirsty brides. “At least I was workin’ with papier-mâché, although some of them…for instance that big [boulder], weighed four hundred pounds. By the time you built the framework it weighed something, but you could get hit with them all right.” (Keaton was, in fact, briefly pinned to the ground by the faux boulder, resulting in a painful injury to one leg but, fortunately, no break.) “Well, I got into the middle of the rock chase and it saved the picture for me, and that was an accident. It hadn’t been framed; it was just an out-and-out accident.”

Keaton was reported as making a few retakes in January 1925, and the final preview took place in Los Angeles the week of February 23. Where before he took a series of headers down the side of a dune before scrambling on, he now skidded into a half-dozen melon-size rocks, dislodging them and then tumbling into an entire field of larger rocks and boulders, all bent on overtaking him as he weaved and leapt, picking up speed in a desperate bid to avoid them. The final shots were masterful, his tiny figure on a steep incline amid a vast, seemingly endless field of rocks, a few eight or ten times his size, some dislodging still others until the whole deadly field is in motion.

“When I’ve got a gag that spreads out,” he said, “I hate to jump a camera into close-ups. So I do everything in the world I can to hold it in that long shot and keep the action rolling. When I do use cuts I still won’t go right into a close-up: I’ll just go in maybe to a full figure, but that’s about as close as I’ll come. Close-ups are too jarring on the screen, and this type of cut can stop an audience from laughing.”

Nothing, however, stopped the preview audience from laughing. The added footage, in fact, whipped them into a frenzy. Metro-Goldwyn executive Edgar J. Mannix wired Nicholas Schenck in New York:

A LAUGHING RIOT. PERSONALLY THINK IT BEST PICTURE HE HAS EVER MADE. THE AUDIENCE JUST ONE CONTINUOUS LAUGH FROM START TO FINISH.

It may not have been coincidental that when Joe Schenck allowed himself to be seduced into Seven Chances, he was in talks to join United Artists as a producer with a slate of pictures beyond what just the Talmadge sisters and Buster Keaton could deliver. Industry insiders knew Schenck’s properties were in play as early as July 1924, when a break between Schenck and First National was considered imminent, Schenck reportedly unhappy with the way they had handled the release of Norma’s feature Secrets. Into the fall, rumors had Schenck luring Louis B. Mayer away from Metro-Goldwyn, the new combine of Metro and Goldwyn Pictures Corporation engineered for Marcus Loew by Joe’s brother Nick. Loew did shut down the old Metro lot across from the Keaton studio, relocating the plant to fancier digs in Culver City, but Joe had no interest in Mayer as a production executive. Instead, he was being wooed by the partners of United Artists, who were Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, D. W. Griffith, and Charlie Chaplin. Griffith was on his way out, and the other three couldn’t produce enough product to sustain a network of regional exchanges. Pickford was struggling to produce two pictures a year, Fairbanks was down to one, and Chaplin was falling into a pattern of delivering a feature comedy every two or three years.

Bringing the Talmadge and Keaton productions to UA would add another six pictures a year to the company’s output. Moreover, Schenck would commit to producing up to six additional films to help fill the pipeline. He hadn’t joined UA earlier out of a sense of loyalty to First National, and because Chaplin was against the idea. “Joe was to be made president,” Chaplin explained in his autobiography. “Although I was fond of Joe, I did not think his contribution was valuable enough to justify his presidency.[*2] Although his wife was a star of some magnitude, she could not match the box office receipts of Mary or Douglas. We had already refused to give Adolph Zukor stock in our company, so why give it to Joe Schenck, who was not as important as Zukor?”

Nevertheless, United Artists was in the red more than half a million dollars, and the situation wasn’t getting any better. It took four days of conferences to bring Chaplin around. The alliance was announced in Los Angeles on October 27 while The Navigator was breaking box office records. Nothing with the Talmadge or Keaton pictures would happen immediately; Norma owed four more releases to First National, Constance five, and Keaton was committed to Metro for another two. For the time being, Schenck would have to fill the void with other attractions, and he quickly moved to sign Rudolph Valentino, late of Famous Players, to a contract calling for three films a year, followed by William S. Hart, who would also commit to three.

Upon the completion of Seven Chances, Keaton’s spring release for 1925, work at the Keaton studio came to a halt for two months and the company’s salaried writers were turned over to other producers. Clyde Bruckman and Joe Mitchell were loaned to Mack Sennett, while Jean Havez was allocated to John Considine, Jr., for a series of pictures featuring a canine star called Peter the Great. The closure, in time, would decimate the Keaton writing staff. First came Tommy Gray’s November 30 death in New York at the age of thirty-six. This left an opening on Harold Lloyd’s staff, Gray last having been on Lloyd’s payroll, and Jean Havez, who had worked previously on A Sailor-Made Man, Dr. Jack, and Grandma’s Boy, was recruited to replace him. Then Havez himself died of a heart attack on February 12, 1925, prompting both Bruckman and Mitchell to go freelance, Bruckman with Lloyd and Monty Banks, Mitchell with Paramount’s Raymond Griffith, among others. The result was that when Buster Keaton began work on his new picture, he had to start over from scratch.

Following on the success of The Navigator, Seven Chances had its world premiere at the Capitol Theatre in New York on March 15, 1925. As with its predecessor, it led the street in box office, taking in nearly $53,000 for the week. Variety’s Robert Sisk summed up the critical response: “It wasn’t quite up to the Keaton standard, but at that Seven Chances was corking entertainment.” The highlight for virtually everyone was the climactic chase sequence, widely hailed as a masterpiece of the form.

“It is the most uproariously funny pursuit picture which has ever assailed our critical diaphragm,” Frank Vreeland of the Telegram and Evening Mail enthused. “Keaton, who directed for Joseph M. Schenck, starts his comedy effects with the brigade of would-be brides very quietly, and then works the laughter up to fortissimo by a tempo that is as deftly accelerated as if Buster were leading the projection machine operator with a baton. It is a marvelous example of the overwhelming, cumulative effect of repetition on the screen, and Keaton knows just when to poke his spectators in the ribs with his sudden comic thrust. The scenes wherein he dodges an avalanche of boulders that hound him down a hillside very nearly laid us low.”

Business for Seven Chances was equally strong at the McVickers in Chicago, the Palace in Washington, the Stanley in Philadelphia, and the Warfield in San Francisco, leaving only Loew’s State in Los Angeles to report less-than-stellar results, despite raves in the Examiner, Times, Herald, and Record. Seven Chances would eventually score $598,228 in worldwide rentals, placing it well behind the high-water mark of The Navigator but still ahead of all of Keaton’s other feature comedies.

Buster Keaton never said where the idea for Go West came from, but his affinity for animals was well known. Creatures of all types were naturally drawn to him, and when Constance Talmadge gave Natalie a Belgian police dog as a wedding gift, the dog, named Captain, quickly gravitated to Buster and began spending his days at the studio. Over time, Captain became so protective of his master that he had to be kept off the set when Keaton was shooting rough stuff with another actor. The dog spent his nights sleeping on Buster’s bed, and when he went missing one day near the intersection of Gower and Fountain, a classified ad in the Times offered a $100 reward for his return. When Captain was struck by a car on April 5, 1923, work on Three Ages ground to a halt. Buster was inconsolable, and asked Gabe Gabourie’s shop to build a coffin. An all-hands ceremony was held the following day, the workforce in tears, and the dog was laid to rest in a small plot on the studio grounds.

One of the mourners attending Captain’s funeral was a former vaudevillian named Lex Neal, a boyhood pal of Buster’s who was trying his hand at writing for the movies. Keaton had given Neal work as early as 1921. By 1925, Lex was hankering to direct, so Buster amiably put him in charge of his sixth feature comedy. And when Keaton traveled east to attend the opening of Seven Chances, he took Lex Neal along so they could spin story ideas on the train. Neal, fully aware of Buster’s natural empathy (“I’m on the side of the animals,” Keaton would tell his biographer Rudi Blesh), may have been the one who first had the idea of making his new leading lady a cow.

The western had been a staple of the screen since the very beginning, popular with audiences and cheap to produce. But the genre had gained a new measure of respectability with Paramount’s The Covered Wagon (1923) and Fox’s The Iron Horse (1924), big-budget productions that were among the most popular attractions of their respective years. Arbuckle and Keaton had previously burlesqued the conventions of the genre in Out West, but now Keaton was aiming for something more, inserting his familiar character into a modern and nuanced version of the western, a satire in the form of a genuine character study. With a rough outline in hand, he hired a scenarist named Raymond Cannon, who was coming off a year’s contract with Douglas MacLean, to flesh out the story and help gag it up. He also selected a young Jersey cow from California’s vast ranch country as his co-star, a beautiful red-and-white-patterned bovine he named Brown Eyes.

In May, Keaton located five thousand cows in a herd near Fort Worth and applied to the chamber of commerce for permission to drive them through the city’s business district for the film’s finale. The scene, according to his wire, was to show “about 400 head of cattle stampeding down Main Street and milling about the Texas Hotel, together with other appropriate atmospheric scenes.” The city fathers assumed he was remembering the place the way it was back when he was a child in vaudeville, when dirt roads and frame businesses were still common. Keaton’s telegram went on to suggest that the shots could be made “on a Sunday when everything is quiet and dull.” Now taking offense, the authorities wired back and suggested that he pick some other town for his horse opera, such as Cromwell, Oklahoma. “Besides,” they said, “the cows wouldn’t like it.”

Keaton took great pains in training Brown Eyes for her part in the picture. He began by leading her around the studio on a rope, rewarding her with carrots until she became used to both the rope and the treats. Then he substituted a string for the rope, and finally a thread for the string. “I never had a more affectionate pet or a more obedient one,” he said. “After a while I was able to walk her through doors, in and out of sets, even past bright lights. The only difficulty we had was when I sat down and she tried to climb into my lap.”

Production got under way in Los Angeles on May 23, while studio carpenter H. B. “Harry” Barnes and electrician Denver Harmon were dispatched to Arizona to oversee the construction of a bunkhouse, blacksmith shop, and various other structures needed for the film’s exteriors. Two weeks later, Keaton, accompanied by cast, crew, and three carloads of equipment, arrived in Kingman, establishing an office at the Hotel Beale across from the Santa Fe terminal.[*3] A convoy of cars and trucks then wended its way north about sixty miles to George “Tap” Duncan’s massive Diamond Bar Ranch, specifically a portion of the Diamond Bar known locally as Valley Ranch. Brown Eyes got there via truck a few days later, traveling with a long-eared mule Keaton was to ride in the picture and attended by two “valets” and a veterinarian. So distinctive were her markings that Brown Eyes was insured for $100,000 against losses should she have to be replaced.

“I didn’t take her on location until I had her perfectly trained to obey my orders,” said Keaton. “Everything went fine until we got Brown Eyes out there on the steaming hot desert. There I couldn’t do a thing with her, not one thing. We were mystified until a rancher told us, ‘That cow’s in heat. She won’t be a bit of use to you until she’s over that.’

“ ‘How long does that take?’ I asked.

“ ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘about ten days or so.’

“We had thirty people in the unit on location….I did the only sensible thing. I ordered her let out of the corral so she could find an affectionate and empathy-loaded bull for herself. She picked a bull, but he was not affectionate. In fact he snubbed her by walking away.” A second attempt went even worse. “There was nothing to do after that but wait for our cow to get out of heat. We spent our time taking shots of the lovely country all around us, but later never figured out how to use that film. When Brown Eyes finally was ready to turn her attention to movie-making again, we did fine with her.”

By Hollywood standards, filming at the Duncan ranch was roughing it. “We were really out in open country…four cameramen (that’s [including] the assistants), electrician generally takes about three men with him (because we took a generator, which takes a couple of men), technical man takes a couple of dozen carpenters, a prop man must take about four extra helpers with him….Then we house ’em up there, see—we take tents and everything else and a portable kitchen.”

The bunkhouse had been built out so that male members of the cast could live in it, while actress Kathleen Myers, even more incidental than usual as the obligatory girl, occupied a suite in the main ranch house. Based at the Beale, Harry Barnes made the daily trip from Kingman to the ranch and back, as did a truck loaded with supplies. Barnes also arranged for the shipment of exposed film to the coast for processing. The days were so hot they had to pack ice around the cameras to keep the emulsion from melting, while winds and flash rainstorms played hell with the schedule. Still, at well over a million acres, there was something inspiring about the Diamond Bar.

“I always preferred working on location,” Keaton said, “because more good gags suggested themselves in new and unfamiliar surroundings.”

Buster’s character is Friendless, a homeless drifter who goes west after heeding Horace Greeley’s immortal dictum. He finds work as a ranch hand at the Diamond Bar, where he meets Brown Eyes, a dairy cow destined for the slaughterhouse because she’s gone dry. Friendless removes a rock that has wedged itself in her hoof, shows it to her, then dutifully buries it in the dusty soil. Tipping his hat, he walks on, only to catch his foot in a hole. While he’s trying to free himself, a menacing bull takes notice and prepares to charge. Racing to his rescue, the Jersey inserts herself between Friendless and his attacker, staring the bull down and backing him off.

Friendless thanks the cow, patting her on the back and giving her a little kiss on the head. Then he’s off again, but this time Brown Eyes is right alongside. He notices, stops, is perplexed at first, reproving even, but then he extends a hand and she begins to lick it. As he slowly draws the hand away, he regards it with disbelief. A bond has been formed between these two outcasts, and Keaton’s natural economy as an actor makes the moment all the more powerful, a brush with genuine pathos he rarely permitted himself. Caressing her, his devotion to Brown Eyes is now clear, and they become inseparable companions. “I was going to do everything I possibly could to keep that cow from being sent to the slaughterhouse,” he said. “I only had that one thing in mind.”

Brown Eyes follows Friendless into the bunkhouse—a breach of ranch etiquette—and they are both summarily banished to the barn. He brings her water, cloaks her in a blanket, and when a pair of wolves appear on the horizon, he grabs a rifle and stands guard over her. The next day he is out on chores when she is to be branded for market. He runs to her rescue, hides her in the brush, and when ordered to do the branding himself, manages to fake the job with a safety razor. Still, the rancher must ship a thousand head—he can hold out no longer—and Friendless, increasingly desperate, doesn’t have the money to buy her himself.

The loading of the cattle at Hackberry, the major shipping point in Mohave County, had to wait until the stockyards had been cleared of livestock and there was room for the movie cows to take their place. As the train pulls out, Friendless and Brown Eyes stand side by side in one of the open cars, unsure of how to escape a fate dictated by the brutal realities of the marketplace. The train is attacked by a rival rancher’s men, and when it pulls away in the resulting melee, Friendless discovers he is the only human left aboard and that it is up to him alone to keep it on course.

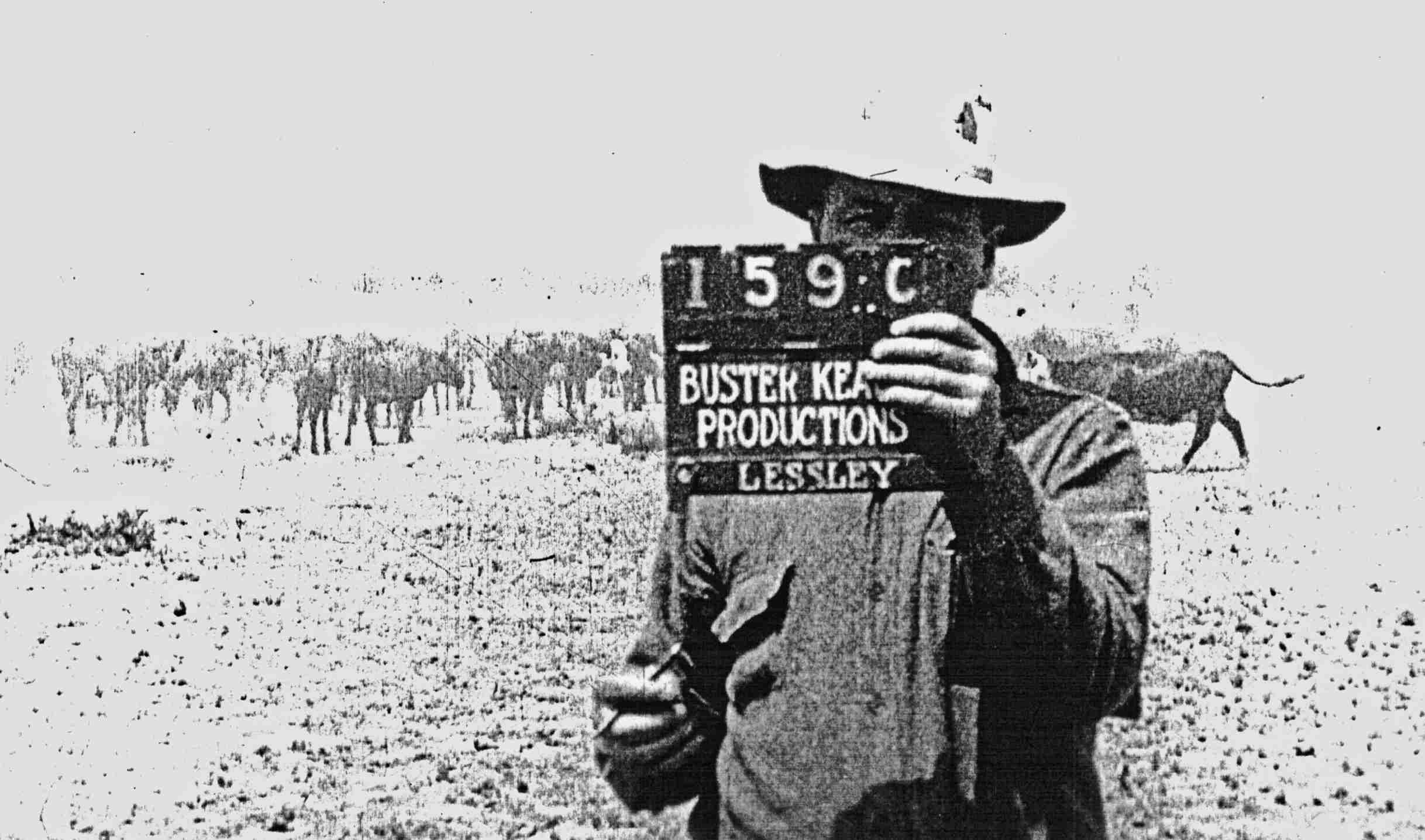

Keaton prepares to signal action with a revolver while directing Go West on location in Arizona.

After nearly three weeks of location work in Arizona, the Go West company returned to the Keaton studio for interiors and to prepare for an epic cattle drive through the streets of Los Angeles that was set to begin shooting the first week in August.

Friendless and Brown Eyes beat a retreat when the train pulls into the Santa Fe depot east of downtown, only to recall that the rancher and his daughter will be ruined if the cattle don’t make it all the way to the stockyards.

“I brought ’em up Seventh Street to Spring Street,” Keaton related in a 1958 interview. “And we put cowboys off on every side street to stop people in automobiles from comin’ into it. And then put our own cars with people in there. And I brought three hundred head of steers up that street. I’d hate to ask permission to do that today.”

Staged against a clever mix of city streets and standing sets, the drive builds to a raucous climax as the cattle invade businesses, customers scattering in all directions. Towel-wrapped men escape a Turkish bath just ahead of a particularly large-horned intruder. At a barbershop, Joe Keaton, lathered for a shave, is surrounded by steers, one casually licking the soap from his face. A department store erupts in chaos as dozens of animals arrive, and Friendless is barely able to keep them all moving. “But then I thought that by goin’ in a store, and I saw a costume place, and I saw a devil’s suit (this was red)—well, bulls and steers don’t like red, they’ll chase it. ’Course I was tryin’ to lead ’em towards the slaughterhouse. I put that suit on and I thought I’d get a funny chase sequence and have the cows get a little too close to me and [I’d] get scared. Then [I’d] really put on speed tryin’ to get away from ’em. But I couldn’t do it with steers—[the] steers wouldn’t chase me. I actually ran and had cowboys pushing ’em as fast as they could go, and I fell down in front of ’em and let ’em get within about ten feet of me before I got to my feet. But as I moved, they stopped too. They piled up on each other. They didn’t mind a stampede at all. But they wouldn’t come near me. Well, that kind of hurt when you think that’s going to be your big finish chase sequence. We had to trick it from all angles.”

To film the cattle drive through downtown Los Angeles for Go West, Keaton incorporated actual city locations with business district exteriors, such as this one, filmed on the Metro lot.

The police are dispatched, then the fire department, their hoses soaking the cops as well as bystanders and passing dignitaries. Brown Eyes breaks free of the auto park where Friendless has checked her for safekeeping and overtakes him. He leaps astride her, still clad in his red devil’s outfit, and together they lead the herd to its final destination just as the ranch owner and his daughter are pulling up. Friendless unmounts, and the rancher pumps his hand gratefully.

“My home and anything I have is yours for the asking,” he says.

After a moment, Friendless gestures in the direction of the girl. “I want her,” he says.

The rancher thinks Friendless means his daughter, but then Friendless walks right past her, leading Brown Eyes into view. With the cow loaded into the back seat of the car, Friendless once again at her side, they drive off, rounding a corner, Friendless now deep in conversation with the rancher’s daughter, and Brown Eyes gently nuzzling her father’s hat.

While Keaton was cutting Go West, it fell to Lou Anger and his staff to disperse the cattle leased for the film. Some were returned to the Duncan ranch, others to their owners in Texas. Brown Eyes, meanwhile, was given a permanent home on the Keaton lot, where it was thought she might be starred, like a bovine Rin Tin Tin, in a future production. When it came time to preview the picture, Keaton was certain he had a flop on his hands. His problems with the cattle drive left him convinced it moved too slowly, that he should have been shown “tearing for his life” with the herd furiously at his heels. “We didn’t dare speed them up,” he said of the steers, “or we would have had a real stampede.” Then a gag he thought as surefire as the school of fish in The Navigator came up empty, and he was at a loss to explain why.

The scene in question threatened to put Keaton at odds with his public image. Eager to win enough money to buy Brown Eyes from the rancher, Friendless joins in a bunkhouse game of poker. He bets the house, then watches the ranch hand opposite him deal himself an ace from the bottom of the deck. Friendless has no choice but to call him on it, causing the man to unholster his gun and point it directly at him. “When you say that—SMILE,” he says, mirroring a famous scene in Owen Wister’s The Virginian.

“Well,” said Keaton, “because I’m known as frozen face, blank pan, we thought that if you did that to me, an audience would say, ‘Oh my God, he can’t smile. He’s gone. He’s dead.’ But it didn’t strike an audience as funny at all; they just felt sorry for me.” Later, he decided the audience didn’t even necessarily feel sorry for him: “Our mistake probably was that we had counted on something that was outside the picture at the particular moment.” The scene was too crucial to cut, and the action was needed even if it didn’t draw a laugh. “We didn’t find out until the preview, and it put a hole in my scene right there and then. Of course, I got out of it the best way I could, but we run into these lulls every now and then.”

With Go West completed, Keaton loaned Ray Cannon to Universal for a Reginald Denny comedy and left for New York with Nat, her sister Dutch, and their mother, ostensibly to confer with Joe Schenck and see to release plans for the new picture, but more directly to shuttle between Washington and Pittsburgh for the World Series. Baseball had assumed an increasingly important role in Keaton’s life, and the studio team, known widely as the Buster Keaton Nine, had captured three state championships. The Nine were frequently in the papers, playing municipal teams and athletic clubs as far north as Oxnard and highlighting the standout work of their captain as well as first baseman Ernie Orsatti, who did prop and doubling work around the lot and was trusted with such critical tasks as pumping Buster’s air during the underwater scenes for The Navigator. Other studios had teams as well: Douglas MacLean’s business staff, his writers and visitors, played daily on the FBO lot, and Harold Lloyd had not only a baseball team but a handball crew as well. Yet no Hollywood team seemed to inspire the attention that naturally accrued to the Keaton organization.

Ernie Orsatti was so good that one day in 1925 he arrived at work and found a new set of luggage and a check waiting for him…and he was told that he was fired. Keaton handed him a contract to play for the Vernon Tigers, in which he retained an interest, but Orsatti played just six games with the Tigers before he was sent to Cedar Rapids as part of the Mississippi Valley League. By 1926, he would be fielding in the minor leagues for the St. Louis Cardinals, on his way to the majors, where he would enjoy a career lasting into the mid-1930s.

Buster Keaton observed his thirtieth birthday in New York on October 4, 1925. Then he trained to Pittsburgh for the first game of the World Series, leaving Nat and her sisters to immerse themselves in the autumn shopping season. He was back on the sixteenth, the series having gone to the Pirates after seven games, and steeled himself for the opening of Go West on October 25. It was the Capitol’s sixth-anniversary attraction, and the advance ads played up Brown Eyes over her human co-star, one going so far as to position her as “a new screen vampire.” Again, Buster was on hand opening day, and his name on-screen elicited a burst of applause. The theater was jammed, although the week’s business wouldn’t quite land on a par with Seven Chances. While nobody accused director Keaton (“assisted,” according to the opening credits, by Lex Neal) of delivering belly laughs, a plurality of reviewers for the trades and the dailies acknowledged the charm and originality of his most personal feature.

One of the strongest responses to Go West came from the Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Carl Sandburg, who was moonlighting as movie critic for the Chicago Daily News. “It seems rather silly to say that any screen comedy will leave unforgettable impressions on you,” Sandburg wrote, “but that seems exactly what Buster Keaton’s Go West is likely to do at McVickers Theater this week. Although the theater at times is explosive with hearty guffaws, Go West may not be the funniest thing that sour-faced Buster has ever done, but it is by far the most enjoyable bit of humor this writer has seen from the Keaton fun factory. This comedian comes close to the Chaplinesque in his serious comedy. Buster is one of the few comedians of the screen at whom you can laugh without feeling a bit ridiculous yourself.”

Keaton always struggled with Go West, and in later years tended to distance himself from it. “Some parts I like,” he allowed in 1958, “but as a picture, in general, I didn’t care for it.” He always looked upon the roundup with disappointment, but the picture may also have struck too personal a note with him, something very private in his character that he didn’t want revealed. In the end, Go West played to $50,300 during an off week on Broadway, a bit less than Seven Chances. In comparison, Harold Lloyd’s The Freshman was in its seventh week at the much smaller Colony, where it took in $30,500 and looked certain to last a full ten weeks. Where Keaton represented an abstraction to American audiences, Lloyd was the real deal, an energetic boy from the Midwest always eager to make good. However popular Chaplin and Keaton were internationally, it was Lloyd who topped the box office polls in the United States and who would remain a big star until talkies and middle age took their inevitable toll.

During Keaton’s previous trip to New York, he had acquired an original story by Robert Sherwood, his indefatigable booster in the pages of Life. Sherwood, whose first Broadway success, The Road to Rome, would appear in 1927, had conceived a Navigator-like story that takes place in the middle of Manhattan. “I’m working on top of the skeleton structure of a new skyscraper, forty stories above the ground,” Keaton related in a talk with Paul Gallico. “I got the girl, the daughter of the architect, up there with me, only her old man don’t know this. We got up there on one of those open elevators which goes down again. And just at that moment there’s a strike and all the boys walk off the job. Now the girl and I are up there, no food, no water, no way to get down, marooned on a desert island, kind of, in the heart of New York.

“That’s a great situation, only Sherwood hasn’t got it solved how to get us out of it. We work and we work and we work on it. And Bob keeps saying, ‘Don’t worry, Buster. I’ll get you down out of there.’ Every time I see him he says that. But he never solves it, and eventually we forget about it.” The story, titled The Skyscraper, was announced as Keaton’s next picture in March 1925, but then, with Sherwood unable to crack the story, Go West took priority.

“[Nine] years later,” Keaton continued, “I’m making a film in England and sitting in the lobby at Claridge’s when in walks this guy with the moustache, nine feet tall, and I recognize Sherwood. He recognizes me, too, because he comes over to me and says, ‘Don’t worry, Buster, I’ll get you down out of there…’ and keeps right on going, and that’s the last I ever saw of him.”

Keaton made another story purchase in New York that spring, the film rights to a newish musical titled Battling Buttler, which had occupied the Selwyn Theatre on Forty-Second Street since the previous October. Buttler was a loose Americanization of a British original similarly titled Battling Butler, a good-natured stage vehicle for the hugely popular actor-manager Jack Buchanan. Although the contract required screen billing for music and lyrics, Keaton was interested solely in the story line, the tale of two men with the same name, one of whom assumes the identity of the other, a famous prizefighter, in order to get away on alleged training trips from a domineering wife. When he’s caught, he has to keep up the pretense, prompting the real Battling Buttler to see to it that he has to fight an actual opponent in a title match.

Ray Cannon stayed with Universal and never returned to the Keaton studio. Though no reason was ever given, Keaton’s general dissatisfaction with Go West may have been a contributing factor. Lex Neal remained as gagman, story constructionist, and title writer, and, by some accounts, co-director. Still, Buster seemed to value the Broadway credentials that men like Jean Havez and Tommy Gray had brought to the team, and in short order he signed Paul Gerard Smith, who wrote revue sketches as well as the book and lyrics to a show called Keep Kool, and Charles Smith, a former vaudeville comic with ties to Joe Schenck through writer-director Roland West. Keaton also brought on a New York–based publicist named Al Boasberg, who was gaining notice as a freelance gagman. In Boasberg’s case, Keaton insisted on a probationary period of six weeks with an option for a full year, and although he picked up the option, he remembered Boasberg as a “terrible flop when he tried to do sight gags for us. So were a hundred other writers we imported from New York. It is possible, of course, that we kept sending for the wrong ones.”

One of the primary changes Keaton and his new staff made to Battling Buttler was to have a spirited girl in place of the wife, the Keaton character never having been particularly suited to the role of a henpecked husband. Actress Sally O’Neill was borrowed from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for the part, and filming began the week of January 4, 1926, in Kernville, 160 miles north of Los Angeles, where four weeks of exteriors were made. Keaton’s Alfred Butler (reverting to the simpler British spelling of the name) is a rich, pampered twit in the grand tradition of Bertie the Lamb and Rollo Treadway, all the better to drop him into a situation far removed from anything he’s ever experienced. His parents—particularly his disgusted father—want to send him on a hunting and fishing trip. “Yes—get a camping outfit—go out and rough it,” the old man tells him. “Maybe it will make a man out of you if you have to take care of yourself for a while.” Alfred takes his loyal valet (Snitz Edwards) with him, and is proving thoroughly incompetent at everything he attempts when he meets the local Mountain Girl and is instantly smitten.

“Saturday evening was picture night at the Odd Fellows Hall,” William B. Smith reported in The Bakersfield Californian, “and we had a good picture, too. But Buster Keaton, who is ‘roughing it’ in a tuxedo and Rolls-Royce in the brush and woods along the Kern River, had a big battery of powerful arc lights throwing weird effects over the woods and onto the far hillsides. It was snappy cold weather, too, but most of the usual patrons of our picture shows deserted the comfort of the hall to watch the little ‘frozen face’ comedian work up footage in the brush beside the ice cold river. Mr. Keaton and his company will be in Kernville most of this week.”

When the camping and courting scenes were completed, Keaton spent another two and a half weeks in Santa Ynez, north of Santa Barbara, before returning to Hollywood for interiors. A fight between the real Battling Butler and a top-seeded contender was staged at L.A.’s new Olympic Auditorium, while training camp interiors, during which Keaton strained ligaments in his leg and back, were shot at the studio.

“I told the original story that was taken from the stage show,” Keaton said, “except that I had to add my own finish. I couldn’t have done the finish that was in the show…[where] he just finds out in the dressing room up at Madison Square Garden that he don’t have to fight the champion and he promises the girl he’ll never fight again. And of course the girl don’t know but what he did fight. But we knew better than to do that to a motion picture audience. We couldn’t promise ’em for seven reels that I was goin’ to fight in the ring and then not fight. So we staged a fight in the dressing room with the guy who just won the title in the ring—by having bad blood between the fighter and myself. And it worked out swell.”

Keaton smugly poses in a gag shot with welterweight champion Mickey Walker on the set of Battling Butler (1926).

The scene between Keaton and actor Francis McDonald, who was a pretty good boxer in his own right, was staged at the Keaton studio before a grouping of fight professionals that included welterweight champion Mickey Walker and Walker’s manager, Jack “Doc” Kearns. It’s McDonald’s character, the prizefighter, who corners Keaton’s Butler in a fit of jealousy, and Keaton wanted the unrehearsed action as real as they could make it. Covered by two cameras in tight quarters, he saw no way they could completely pull their punches, and McDonald’s only instructions were to take a dive, giving the other Alfred a private victory.

Keaton’s Butler cowers, pleads, shields himself, as his valet and the fighter’s wife watch horrified from the doorway. Finally, he can stand no more and erupts in a furious barrage of punches, aggressively downing his opponent and then picking him up so that he can pummel him more. Keaton, the consummate actor, displays genuine anger in the scene, almost to the point of breaking character. It is a brutal, shocking, merciless display, utterly convincing.

“That’s the greatest battle I ever saw outside of a ring,” Walker proclaimed when the whole thing was over. “I mean it, too. If Buster and McDonald had put on that scrap before a fight club, they’d have had the crowd on its feet from start to finish.”

Kearns, who was famous for managing Jack Dempsey, agreed. “Best fight I’ve ever seen enacted before the cameras,” he said. “The picture Buster was making may be a comedy, but there was nothing funny about that battle. It was a wow. What a beating those boys did give each other.”

Keaton completed Battling Butler in early March, just as Joe Schenck was announcing United Artists’ ambitious slate of feature productions for the 1926–27 season. Included were two pictures from Mary Pickford, one from Douglas Fairbanks (The Black Pirate), two from Rudolph Valentino, one from Charlie Chaplin (The Circus), three from Samuel Goldwyn, and two from Buster Keaton. Battling Butler fulfilled his commitment to Metro-Goldwyn (now M-G-M) and Schenck was moving him to UA at a time when he was assembling the most prestigious roster of talent in the industry. Both John Barrymore and Gloria Swanson were now stars for United Artists, and Norma Talmadge would soon be joining them.

In terms of a picture, all they had from Keaton was a title, and he was encouraged to make it something special, a comedy that would stand up to Chaplin’s first movie in two years, to the Technicolor Black Pirate, and to such Goldwyn productions as Stella Dallas and The Winning of Barbara Worth. “We will never have more than fifteen pictures a year,” Schenck said in an interview with Motion Picture News, “and none of these will be permitted to fall below the present quality. Each picture must have something big about it.”

All the New York office knew about the new Keaton picture was that it seemed to have a military theme. UA’s two-page display announcement in The Film Daily featured the star’s profile against a generic pattern of soldiers marching stiffly in parade dress. It was, it turned out, a wildly inappropriate representation of the unconventional comedy Keaton had in mind.