13

The General

THE HOUSE ON MUIRFIELD ROAD lasted eighteen months before it too was consigned to history. Weary of his wife’s pattern of elation and disillusionment, Buster Keaton attempted an intervention of sorts. Where Nat was forever on the lookout for the next, seemingly better place to live, her husband arrived at the conclusion that she needed a house she wouldn’t find in the local inventory—one that no one else had ever occupied, virgin space rather than, as he reasoned it, “somebody else’s hand-me-down.” In 1925, he bought a couple of undeveloped lots in Beverly Hills and secretly had a three-bedroom Spanish-style house designed, built, landscaped, and furnished on the smaller of the two. “It cost only $33,000,” he said proudly, “but it was on a large lot, had a swimming pool, and was ideal for the four of us. I was so sure of this that I wouldn’t let my wife see it until it was ready to move into. I wanted to surprise her.”

He imagined they’d drive by the new house, casually stop to have a look, and when Nat exclaimed something along the lines of “It’s a dream of a home,” he’d tell her with a flourish that it was all hers. But it didn’t quite work out that way—principally because the house, with Gabe Gabourie’s help, was of Buster’s design, not Natalie’s.

“In the first place,” she said tightly, “it has no room for the governess. Where would she sleep?” Bernice Mannix, wife of Metro-Goldwyn executive Eddie Mannix, was along for the big reveal, and genuinely loved what Buster had conceived and built at 516 North Linden. “If you really want it, Bernice,” he said, impulsively throwing in the towel, “it’s yours. Have Eddie look at it, and if he likes it I will sell it to you.”

The only solution, he conceded, was to build a showplace on a grand scale, something that indulged Nat’s every whim. They sold the place on Muirfield for $85,000, pocketing a small profit, and moved into a nearby rental owned by Peg Talmadge. Then they began the arduous process of creating one of the most elaborate estates in Beverly Hills, for which they retained a Canadian-born architect named Gene Verge, who would go on to local prominence as a designer of hospitals, churches, and stately private residences. By the end of 1925, Verge had completed plans for a mansion in the spirit of the Italian Renaissance, ten thousand square feet on three and a half acres of prime Beverly Hills real estate. It would take $200,000 and the better part of a year to build.

Keaton always credited Clyde Bruckman with the idea for The General—and Bruckman wasn’t even working for him at the time. After Jean Havez’s death, Bruck had gone freelance, working at intervals with Monty Banks, Eddie Cline, and Harold Lloyd. A prodigious reader, he had come across The Great Locomotive Chase, an account of a daring Union raid into Georgia during the Civil War. The book by William Pittenger, one of the participants in the expedition, had been around for decades in various forms, and it’s likely that Bruckman would never have seen the comic potential in the story had he encountered it under its original title, Daring and Suffering, or the later Capturing a Locomotive. But the apt combination of the words “Locomotive” and “Chase” in the title of the book’s third edition, published in 1891, must surely have brought Keaton to mind.

“Clyde Bruckman run into this book…and it was a pip,” Buster reminisced. “[Bruckman] says, ‘Well, it’s awful heavy for us to attempt, because when we got that much plot and story to tell, it means we’re goin’ to have a lot of film with no laughs in it. But we won’t worry too much about it if we can get the plot all [laid out] in that first reel, and our characters—believable characters—all planted, and then go ahead and let it roll.’ ” Of the book’s nearly five hundred pages, the story to be told on-screen consumed just 128. “Nothing I had ever heard so fired my imagination,” wrote Pittenger, a first corporal in the Union Army. “The idea of a few disguised men suddenly seizing a train far within the enemy’s lines, cutting the telegraph wires, burning bridges, and leaving the foe in helpless rage behind, was the very sublimity and romance of war.”

Keaton instantly knew his solitary character wouldn’t fit in with the twenty-one volunteers under the leadership of James J. Andrews, a Union spy and contraband merchant. Rather, since this was, as he put it, a page from history, it was important to acknowledge up front that the audience would already know how it all turned out for the South. “They lost the war anyhow, so the audience resents it. We knew better. Don’t tell the story from the Northerners’ side—tell it from the Southerners’ side.” The character he envisioned for himself would be a Confederate engineer whose beloved locomotive, the General, is the one the spies seize in the raid and pilot northward toward Tennessee.

With such a complex series of events, Bruckman was tasked with the job of getting it all on paper, paring away the many pages of extraneous detail and boiling the book down to its essence. The result was a preliminary 116-page script, by far the most complete scenario with which Keaton had ever started a film. With the document at hand and the book cast aside, he began focusing his mind on the emerging continuity, which would see countless changes. “The moment you give me a locomotive and things like that to play with, as a rule I find some way of getting laughs with it. But the original locomotive chase ended when I found myself in Northern territory and had to desert. From then on it was my invention in order to get a complete plot. It had nothing to do with the Civil War.”

In April, with Battling Butler cut and titled, and the story for The General far from settled, Keaton, Gabe Gabourie, and staff writer Paul Gerard Smith traveled to New Orleans and Atlanta to scout locations. Normally, Buster would have included Elgin Lessley on such a trip, but after five years with Keaton, Lessley had been recruited by Harry Langdon to photograph his first feature comedy, Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, and would remain with Langdon for a total of five features—the entire arc of Langdon’s career as a first-rank comedian. Shrewdly, Keaton chose to replace him on Battling Butler with veteran cinematographer Devereaux “Dev” Jennings, who had more than fifty pictures to his credit, none of which were comedies. Battling Butler was a relatively easy picture to shoot; The General would be anything but.

“I went to the original location from Atlanta, Georgia, up to Chattanooga,” Keaton remembered, “and the scenery didn’t look very good. It looked terrible. The railroad tracks I couldn’t use at all because the Civil War trains were narrow gauge, and those railroad beds of the time were pretty crude.[*1] They didn’t have so much gravel rock to put between the ties, and then you saw grass growing between the ties every place you saw the railroad, darn near.” With the authentic locales ruled out as viable locations, Bert Jackson, Keaton’s location manager and chief property man, was dispatched to the verdant lumbering regions of the Pacific Northwest, where rivers and logging trains were plentiful, and where the terrains looked more authentically Southern than the South itself. It was Jackson who identified Oregon’s Cottage Grove as the best filming site and, after seeing to preliminaries, such as cooperation from the Oregon, Pacific & Eastern, a local short line railroad, wired the studio to say he had found exactly what they were after.

By the time Keaton and his party, which included Natalie, Bruckman, and Gabourie, arrived in Cottage Grove on May 7, 1926, Jackson had spent four furious days lining up meetings and tours, and sweating the logistical details of a major production based so far from home. Go West was three weeks in Arizona; The General would be at least two months on the ground in Oregon, possibly more. Fortunately, Cottage Grove was just twenty-two miles south of Eugene, the second-largest city in the state, assuring quick access to supplies not so easily found in a wilderness town of two thousand. Keaton was all business that day, impassively studying the community and climbing over and through locomotives that might be used in the film.

“A person has to work hard if he is going to be successful,” he explained to a local reporter, “and we have to keep going all the time.” He inspected an abandoned lumber camp that might double as a set, and arranged to purchase two engines, one of which, a wood-burning specimen from the Anderson & Middleton logging camp called Old Four Spot, would be sacrificed by running it across a burning bridge.

“I have looked all over the country for a place like this,” he said with a grin of satisfaction. “It is just what I want.”

Keaton was a couple of days in Lane County before returning to Hollywood, leaving Bert Jackson to prepare for work at four different filming sites—two on the Row River; one at Dorena, a little village in the foothills of the Calapooya Mountains; and one at a nearby logging settlement called Culp Creek. Soon, representatives of the Dallas Machine and Locomotive Works were on site with plans to bring the engines cosmetically into line with their historic counterparts. Back in Hollywood, Keaton oversaw casting for the new picture, selecting actress Marion Mack for the role of his fiancée, who would come to be known as Annabelle Lee.

“Buster was looking for an old-fashioned girl with long, curly hair…because they wanted everything to look just right for the Civil War period,” said Mack. “Well, Percy Westmore, who was making up Norma Talmadge for some picture, heard this from her…and Percy mentioned that he knew a girl with just the right hair, because he had been my makeup man on [the recently completed] Carnival Girl. And Norma said to Percy he should try to find out if I was available, and he called me and the first thing he said was, ‘I hope you still have those long curls you had in Carnival Girl.’ Well…this was the year everyone was bobbing their hair, and so, only a couple of days before, I cut my hair short, too, and I told it to Percy. And he said, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll give you a fall or something.’ ”

In lieu of an audition, Mack sent over a print of her 1923 feature Mary of the Movies, and a meeting was subsequently arranged with Keaton, Bruckman, and Lou Anger. “Buster didn’t say much,” she remembered. “Clyde Bruckman was a nice person. He didn’t seem to have a terrific sense of humor. He seemed more like a college teacher-type person. But Lou Anger was very much the executive type, the tummy and cigar type. He didn’t seem too impressed with me, Mr. Anger didn’t. I wanted to have a hairdresser go along with me. They said, ‘Okay, we’ll give you the part.’ And I said, ‘I have to have my own hairdresser sent with me up on location—and that’s the only way I’ll sign the contract.’ And so Mr. Anger [sneeringly] says, ‘My, you are demanding, aren’t you?’ But I got the hairdresser.”

Other principals selected for the cast were Glen Cavender as the leader of the raiders, actor James Farley, baseball star “Turkey” Mike Donlin, the great Irish comedian Tom Nawn, and Joe Keaton, all as Union generals. Snitz Edwards, compacted veteran of Seven Chances and Battling Butler, was chosen for a distinctive cameo. Pressed into service were gagman Charles Smith as Annabelle’s father, and construction supervisor Frank Barnes as her brother.

When Keaton returned to Cottage Grove on May 28, Nat was again with him, as were Bruckman, Gabourie, and Dev Jennings and their wives. His hair was grown long in the style of the period, and he had been preceded by eighteen carloads of equipment, some twelve hundred costumes, and an advance party of twenty. Sets were already under construction, while the upper floor of the Long and Cruson Service Garage, formerly a Moose lodge, was in the process of being transformed into makeup and wardrobe departments. Cannons, prairie schooners, wagons, and a stagecoach had been shipped in for the picture. Houses, big and small, were being built in sections so they could easily be moved to where they were needed.

Keaton spent Memorial Day weekend inspecting the filming sites with Gabourie—who had assumed the role of production manager—Jackson, and business manager Al Gilmore, while others picnicked on the banks of the Row River or sampled the fishing. Several spots in Cottage Grove itself were being dressed to represent the town of Marietta, Georgia, including a section of the original settlement called Slab Town, in which many old structures survived.

The last day of May marked the Keatons’ fifth wedding anniversary, and a surprise banquet was tendered at the Bartell Hotel by about thirty members of the company. Gabe Gabourie was in charge of the event, and the couple was presented with a pen sketch by the company draftsman. Marion Mack and her husband, producer Louis Lewyn, arrived the following day. Waiting for the first sets to be ready, Keaton stirred up a couple of late-afternoon ball games with the local Methodist church, the first of which was won by the church team 5–3. The local challengers were soon formalized as the Twilight League, while the visitors became known as the Keaton Location Nine.

Frank Barnes had a stretch of Marietta along the railroad line east of town finished on June 3, enabling production on The General to begin on Monday, June 7. With the start of filming imminent, a writer for Eugene’s Morning Register walked the streets of the southern town where the Andrews raid begins, marveling at what Barnes had accomplished in little more than a week:

“The city of Marietta, which has been under construction here, is now completed and a test shot will be made on Sunday. This town site, constructed of new lumber, now has the appearance of having stood for fifty years. The Western and Atlantic railroad station bearing the sign of ‘Marietta’ in faded weather-beaten letters across the front, its two waiting rooms with conspicuous signs ‘colored waiting room’ and ‘white waiting room,’ the faded and dusty blackboard timetable stating No. 3 on time, makes one wonder just a little. A short step or two across the dusty street stands the old Georgia Hotel [and] bar, with shuttered windows of another day. There is the town watering trough, its cracks and joints green with the moss of years, so realistic that one catches himself glancing down to the ground beneath, looking for the puddles in the dust and the steady drip that makes them. Sauntering on up the street you see the City Hall standing, old fashioned yet business-like, with all its outward appearance of needing paint. There is the tailor shop, the trimmer shop, billiard and pool, blacksmith shop and wheelwright, halls, shoe and harness shop, the Southern hotel, the post office, and numerous other business houses. There is the stage stables from which some long line skinner will reel his string of four or six away and hit the trail for Chattanooga perhaps.”

Early scenes captured the arrival of the train at Marietta, the passengers disembarking while Buster, in the character of Johnnie Gray, lovingly inspects the engine, a couple of local boys eagerly miming his actions. “We’d better have a dog or two, lazy ones, in the foreground,” Keaton instructed as he composed a shot. “Better give that colored boy a bundle to carry.”

A week would be given over to Johnnie’s initial scenes with Annabelle, who, with the news that Fort Sumter has been fired upon, sends him off to the recruiting office to be one of the first to join up. His enlistment, however, is denied because he is more valuable to the cause as an engineer. Perceived as a slacker, he is left behind to endure the scorn of the populace, Annabelle’s included. Dejectedly, in what filmmaker James Blue would call “a moment of almost pathetic beauty,” he sits on the coupling rod that connects the great metal wheels of the General and remains there, frozen in place, as the engine begins to move.

“The situation of the picture at that point is that she says, ‘Never speak to me again unless you’re in uniform.’ So the bottom has dropped out of everything, and I’ve got nothing to do but sit down on my engine and think. I don’t know why they rejected me; they didn’t tell me it was because they didn’t want to take a locomotive engineer off his duty. My fireman wants to put the engine away in the roundhouse and doesn’t know that I’m sitting on the cross bar, and starts to take it in. I was running the engine myself through the picture. I could handle the thing so well I was stopping on a dime. But when it came to this shot I asked the engineer whether we could do it. He said, ‘There’s only one danger. A fraction too much steam with these old-fashioned engines and the wheel spins. And if it spins it will kill you then and there.’ We tried it four or five times, and in the end the engineer was satisfied that he could handle it. So we went ahead and did it. I wanted a fade-out laugh for that sequence. Although it’s not a big laugh, it’s cute and funny enough to get me a nice laugh.”

Spectators drove in from as far away as Seattle, crowding the filming sites and hemming in the actors. When the curious jammed in too close, Gabourie or Jackson, or even Keaton himself, would walk over and courteously ask, “Will you please stand back so as not to cast a shadow on the picture?” Someone from the Cottage Grove Sentinel captured the crush of activity surrounding the star-director as he attempted to squeeze in an interview. “As he answered a reporter’s questions, he gave directions for the ball game to start within a few minutes, directed the purchase of balls, gave an order for the entire company to be in the lobby by seven o’clock the next morning, answered half a hundred questions by his production manager or some other official about this and that, described the making of a picture, visited briefly with a stranger who had known him in his childhood and gave the address at which other members of the family could be located, ordered his car, sent for members of the ball team, told the story of the present picture, and a few other things, frequently smiling at something humorous…” So focused was Keaton on the making of the picture that he couldn’t remember his own room number or how many of his people were on site. “Yes, the slapstick is gone,” he acknowledged, reflecting on the dramatic nature of the story. “No longer will folks pay for that kind of stuff. The movie public demands drama, punctuated with comedy. The pictures that go over big are those with comedy situations, and the kind that go over are the kind the producers are going to make. When the public demands something else, something else will be made.”

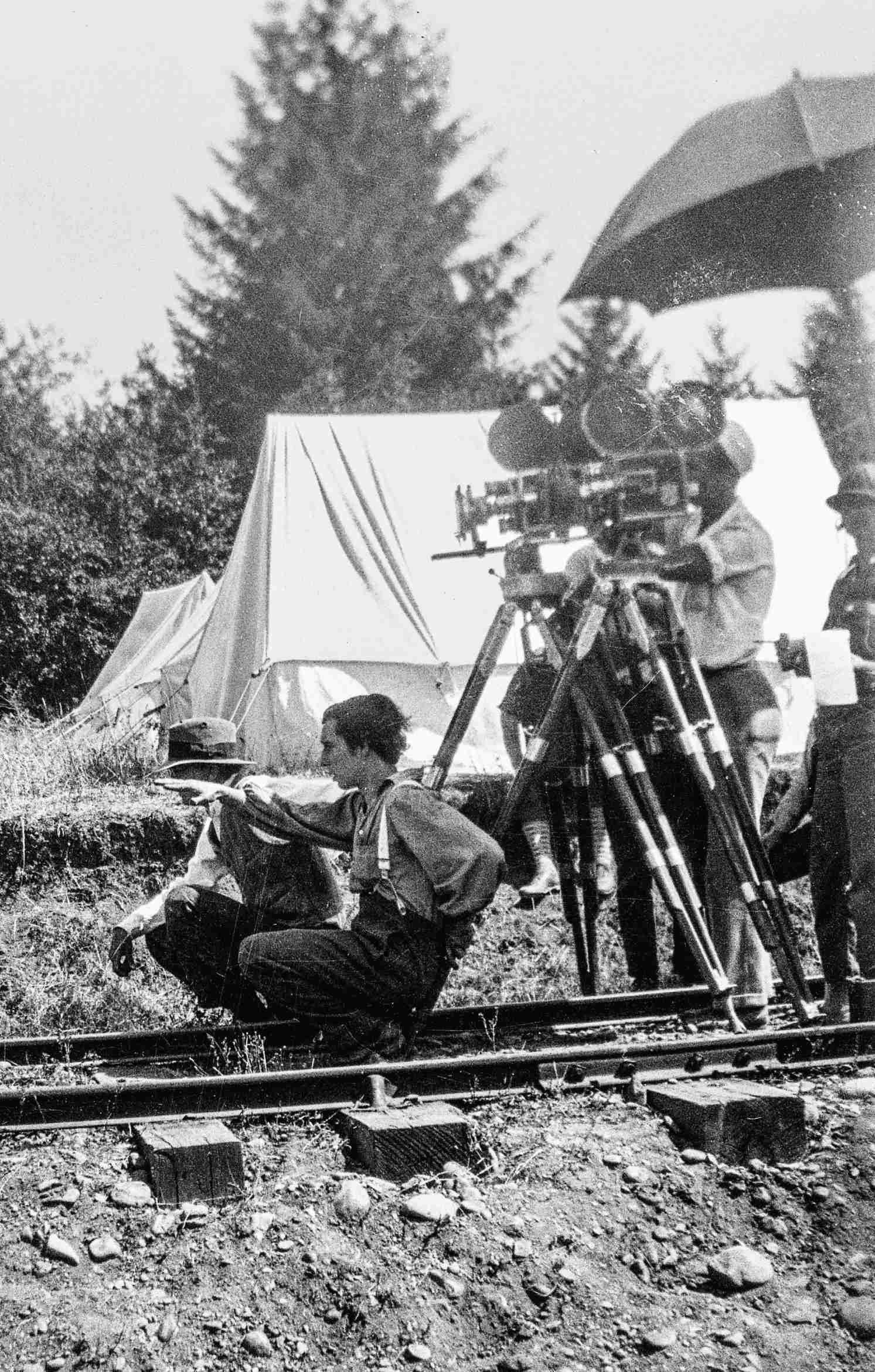

Keaton, in costume, with his camera crew while on location in Cottage Grove, Oregon, for The General. Note the parallel tracks in the foreground, which made the extraordinary traveling shots possible.

The Southern army’s retreat and the advance of the victorious Northerners go completely unnoticed by Johnnie Gray.

It was estimated that shooting at Cottage Grove cost four hundred dollars an hour, whether or not any film got exposed. On Tuesday, work had to be halted when a two-sided drugstore was blown over in a stiff wind, but the front was quickly righted. Then an onlooker stepped into a shot directly behind Buster as he was oiling his engine, spoiling the take, yet all Keaton could do was to smile and do it over. Later, patiently seated in the doorway of a boxcar during a production delay, he took an empty pop bottle, tossed it into the air, and balanced it on the back of his hand. He repeated the trick several times, then once again sent it skyward, sticking a finger up and catching the bottle by its neck. A crowd of onlookers laughed, and Keaton grinned.

On Wednesday, the company used an old planing mill at Dorena to stage the theft of the train at Big Shanty, the Union raiders uncoupling the passenger cars and pulling away with the General, a tender, and three empty boxcars during a stopover for dinner. Johnnie gives chase, first on foot, then on a handcar, just as the actual pursuers did in 1862. Ahead, the raiders are cutting telegraph lines, pulling up rails, and littering the track with crossties. At Kingston, Buster comes across an army encampment and alerts the men to the stolen General, which he thinks has been taken by deserters. They climb aboard a flat car on their own train while Johnnie leaps into its cab and pulls away, unaware the rest of it has come uncoupled, leaving the soldiers stranded at the station. Speeding northward toward Adairsville, he discovers he is alone in his quest to reclaim his engine.

While the company was reconfiguring the town of Marietta to represent Chattanooga and, for later scenes, Calhoun, Keaton turned his attentions to scenes aboard the pursuing engine, the Texas, much of which would be filmed by Dev Jennings and second cameraman Bert “Boots” Haines from a train traveling on a half-mile set of parallel tracks just east of town. These rock-steady images captured brief bits of action, thirty or forty seconds at the most, and then the two trains would have to be backed up to their starting points for another run, a tedious process of stopping and starting until an entire sequence had been completed.[*2]

With the Anderson & Middleton mills closed for their annual Independence Day shutdown, the only other rail traffic to contend with were twice-daily passenger runs, and Bert Jackson was able to get those rescheduled to earlier in the morning and later in the evening for ten consecutive days. Among the crucial scenes to be made during this period was an expertly timed shot involving a rolling cannon Buster uses to fire on the raiders. Bouncing along the track behind the Texas and its tender, the cannon, once lit, adjusts to train itself on Johnnie and the car directly in front of it. He braces for the worst as the engine comes to a bend in the road, taking it out of the line of fire just as the cannon goes off, its shell exploding within feet of the Union men fleeing with the General.

Another sequence inspired by the book, in which the raiders set a boxcar on fire and roll it into a covered bridge, was staged near Disston before hundreds of onlookers. Closer to town, a wheat field became the scene of a Confederate retreat with hundreds of horses, wagons, and soldiers escaping to the South as Buster, traveling north with the Texas and oblivious to the exodus, occupies the foreground, furiously chopping firewood to keep the engine moving. In its sweep and casual majesty, the scene ranks as one of Keaton’s most powerful, particularly when the fleeing Southerners are followed by the advance of the Union army, turning the panorama behind him from gray to blue, the ebb and flow of warfare signaling his passage into enemy territory. Topping off the eventful week was a preview of Battling Butler at the Arcade Theater, which Keaton had been using to screen rushes. In a gesture of thanks, he arranged to have a print of the new picture sent up for a pair of advance showings, both of which played to capacity audiences. The Eugene Guard called it “the best thing we have seen of Buster’s.”

“I staged it exactly the way it happened,” Keaton liked to say of the Andrews Raid. “The Union agents intended to enter from the state of Kentucky, which was a neutral territory, pretending they were coming down to fight for the Southern cause. That was an excuse to get on that train which takes them up to an army camp. Their leader took seven men with him, including two locomotive engineers and a telegraph operator, and he told them that if anything went wrong they were to scatter individually, stick to their stories that they were Kentuckians down to enlist in the Southern army, and then watch for the first opportunity to desert and get back over the line to the North. As soon as they stole that engine they wanted to pull out of there, to disconnect the telegraph and burn bridges and destroy enough track to cripple the Southern army supply route. That was what they intended to do. And I staged the chase exactly the way it happened. Then I rounded out the story of stealing my engine back.”

However useful Clyde Bruckman’s scenario had been in organizing the contours of the plot, it was remarkably free of the comedy highlights that would distinguish the picture. “The script they took with us they hardly went by at all,” said Marion Mack, “except just the next sequence because they had to write the gags that weren’t in it.” Historically, the Andrews Raid ended at Ringgold, Georgia, when the General ran out of steam some twenty miles south of Chattanooga. But in the picture Keaton and Bruckman kept the engine in play so that Johnnie could come upon a meeting of Union generals and learn of plans for their supply trains to unite with the Northern Division at Rock River Bridge, then advance for a surprise attack.

Director Keaton lines up a shot at Carlton, the Union army supply base where Johnnie and Annabelle steal back the General.

Throughout the early filming, much was made of a spectacular shot planned for the third act in which Union soldiers attempt to drive a supply train over a bridge Johnnie has set on fire. The weakened span collapses under the weight of the engine, and it plunges into the river below. It was an idea that came from The Great Locomotive Chase in which the thieves attempt to torch a bridge on the Oostanaula River near Resaca, Georgia, but the dampness of the structure will not permit it to burn. Keaton was dead set against attempting the effect in miniature, knowing the size and spectacle of the thing would make for a thrilling big-screen experience. He surveyed every existing trestle in the region trying to find one suitable to the visual and logistical demands of the scene, and at various times no fewer than four had been picked and rejected, complicating factors being a necessary elevation of seventy-five to a hundred feet and easy access by a spur from the OP&E. Finally, in desperation, a team of four men, headed by Gabe Gabourie, was dispatched one Saturday into the surrounding counties on a mission to identify the best possible candidate. Their conclusion at the end of the day was that the ideal trestle didn’t exist and that Rock River Bridge would have to be built from scratch.

On July 1, a contract was let to begin the design and construction of a 250-foot bridge rising some fifty feet above the jagged rocks of Row River. It would need to be capable of supporting twenty tons of rolling stock, yet collapse into the water on cue. To bring the river up to a depth of twelve feet, a dam at the site near the Culp Creek settlement would also have to be built. By July 7, work had commenced on the span, with a spur five hundred feet in length designed to connect to the main line of the OP&E. The next day, a third engine arrived from Hood River, remodeled to period and renamed the Comet. On July 13, an appeal was made for National Guardsmen from Eugene, Springfield, and Cottage Grove. On July 15, a call went out for five hundred additional men, with tourist sleepers from the Southern Pacific parked on the tracks to accommodate those traveling from long distances. Four days later, confirmation came that the big battle scenes were to be filmed over three days beginning Thursday, July 22, with the collapse of the flaming bridge likely to take place on Friday, July 23.

While preparations went forth, Keaton busied himself playing scenes with Marion Mack, who, as Annabelle Lee, has been held captive by the raiders since the theft of the train. Johnnie rescues her, and the two steal away under the cover of darkness. At daybreak, they discover the General at a bustling army encampment being loaded with supplies. “We’ve got to get back to our lines somehow and warn them of this coming attack,” he tells her. Then he stuffs her into a burlap bag, loads her like a sack of potatoes, and in a quick, decisive move, clobbers a Union officer and brazenly hijacks the engine from under their noses. Soon, Johnnie, Annabelle, and the General are being chased by the Texas and the Comet, both loaded with Union troops.

Mack quickly learned how unpredictable Keaton could be when the cameras were grinding. Stopping briefly when they had to take on water, she was unexpectedly drenched when he artfully positioned her directly in front of the spout. “It really knocked me down,” she said. “It’s a good thing we didn’t have sound movies at the time.” Later, she suggested a gag of her own, where Annabelle, trying to make herself useful, picks up a broom and starts sweeping the cab as the Texas is rapidly gaining on them. Alarmed, Johnnie yanks it from her hands and tells her to add wood to the fire. Compliantly, she picks up a tiny piece, opens the door, and primly tosses it in. Disgusted, he finds an even smaller piece, hands it to her, and watches as she does exactly the same thing. Impulsively, he reaches over and takes her neck in his hands and begins to throttle her. Then, just as quickly, he shifts gears and gives her a kiss.

“I think I got that kiss more for thinking of the gag than anything else,” she said.

The General beats the Northerners to Rock River Bridge, giving Johnnie time to set the bridge on fire before continuing on to Calhoun, a Southern stronghold. At division headquarters, he warns the commanding general of the enemy’s plan, which sends hundreds of Confederate soldiers streaming northward. Back at Rock River, the supply trains are stymied as General Parker arrives on the scene. “That bridge is not burned enough to stop you,” he tells the engineers, “and my men will ford the river.”

Thursday, July 22, was devoted to preparations for the fateful crossing. At two o’clock, a train carrying eight hundred men and about ninety horses arrived at Cottage Grove, where they were marched to the wardrobe depot at Sixth and Main Streets. There they were joined by two hundred boys from the local guard company, and all were issued uniforms and battle paraphernalia. Later the same afternoon, the special train, powered by two logging engines, carried them fifteen miles to a camp at Culp Creek. Only a handful of shots would be made the following day. If all went according to plan, one of them would cost $40,000—the most expensive take in the history of the screen. Were anything to go wrong, the added cost of another run would surely break the bank.

Cars began arriving on Thursday afternoon, with spectators planning to camp near the bridge all night. By four on Friday morning, they lined Row River Road from a quarter mile above the location site to a point about a mile below Culp Creek, leaving hardly any room to get through. Cottage Grove, in fact, cleared out so thoroughly that most merchants closed for the day. Dev Jennings had brought four cameras to Oregon: three Bell & Howells and an Akeley, a versatile camera expressly designed for shooting action footage under field conditions. Two additional camera units were ordered up from Hollywood, making a total of six on hand to capture the fiery crash. Jennings’ own crew consisted of Boots Haines, assistant Elmer Ellsworth, and stills cameraman Byron Houck, who was carrying an eight-by-ten Eastman and a five-by-seven Graflex. Jennings’ principal cameras were stationed down the river about three hundred yards, while two others were on a platform directly across the river on its south side, high above the far end of the bridge to capture the approach of the supply trains and Union troops.

The atmosphere had grown tense by the time Keaton decided he was ready. Rehearsals coordinated the movements of the key visual elements—the cavalry, the foot soldiers, the two engines. “I marched more there than I did in the army,” said Ronald Gilstrap, who belonged to the National Guard and volunteered for picture duty. “We came down this road towards the crossing four times, I think, before they got a shot. The first time some kids were in the road, and another time something else happened. Then Buster Keaton took the engine across the trestle and back.” The General had previously crossed over as Johnnie and Annabelle went about the business of starting the fire.

As director, Keaton was ever present, methodically checking and rechecking things as the morning wore on. “Not satisfied to stand on the camera platform and give orders through a telephone with megaphone attachment, he was here and there on all angles of the location,” the Eugene Guard recorded. Co-director Clyde Bruckman, clad in a red jacket and matching hat, was more conspicuous than useful. “He didn’t direct much of it at all,” said Marion Mack. “He was more like an assistant in the whole film.”

With the timing perfected, the span was weakened by sawing into the timbers from underneath. “There was an awful lot of apprehension about it,” said Grace Matteson, whose father worked as a carpenter on the film. “I can remember my father talking about the decisions they had to make in order to get it just right. There was quite a bit of figuring and arguing.” They eventually decided that strategically placed dynamite would also help the bridge to collapse on cue. Shortly before noon, the structure saturated with gasoline, Keaton called for camera. “Start your action!” he signaled, but then he decided the flames were no good and aborted the take. A custom water cannon powered by a six-cylinder automobile engine extinguished them before any damage was done.

Dinner was called, and the extras went off to mess as the livestock were cared for and watered. Spectators, estimated at three to four thousand, crowded around the numerous hot dog stands and refreshment booths that sprang up like toadstools. It wasn’t until two o’clock that everything was in place for another attempt. The bridge was once again ignited, action again was called, and again the shot was abruptly scuttled as the engine dutifully approached its fate. Down at the far base of the bridge, directly below the flaming timbers, a group of small boys could be seen swimming in the river. The powerful water pump again was trained on the flames, the Texas was once more backed into position, and while the bluecoats retreated with their mounts, Bruckman stormed and fumed at the children. A third attempt was spoiled when some of the soldiers waded into the water at the wrong time, causing yet another half-hour delay.

Before a fourth take was attempted, Keaton had a pile of wood placed at the center of the bridge. Sawdust was strewn all about, and everything was once again saturated with gasoline. Now getting past three o’clock, time was running short. Silence was politely requested of the spectators, and downriver the temporary dam was opened, causing water backed up some three hundred yards to flow through the gorge. Now all eyes were on Keaton as he took his place on the camera platform and signaled powderman Jack Little. Activating a series of electric ignitions with the press of a button, Little caused the bridge to burst into flames. As the fire built, the smell of gasoline permeated the air. At last satisfied, Keaton called “Camera!” and the words “Start your action!” As the Texas charged toward the burning trestle, Union cavalrymen made for the river. When the cowcatcher on the locomotive reached the exact center of the trestle, Little detonated the dynamite charges at the centermost pilings and the span began to buckle. With the Texas and its tender now perfectly centered over the water and clearing the banks on both sides, it fell and dug deep into the bed below. As it sank, black smoke erupting skyward, steam forced from the boiler caused the whistle to blow a mournful dirge. There was an audible gasp from the crowd, and screams could be heard as realistic dummies representing the engineer and fireman were thrown clear of the wreck. One woman fainted, and another grew hysterical as the papier-mâché head of the engineer floated downstream.

With the bridge and the locomotive now a smoldering mass of wreckage, the horses and infantry waded into the river, where they discovered the dam had left the water deeper in places than they expected. Weighted down with heavy uniforms, rifles, and the like, some of the costumed extras had trouble making it across. “I was pulling them out,” said Gilstrap. “I’m a good swimmer, and there were several of us. I pulled four or five fellers up and got them on the bank.” Two men nearly drowned when they found themselves in deep water, and a third, a fifteen-year-old, was hospitalized in critical condition. Visibly relieved when the scene was finally in the can, Keaton was, the Cottage Grove Sentinel reported, “happy as a kid.”

“Come on, gang,” he said, “let’s call it a day.”

Saturday and Sunday were given over to scenes of the climactic battle between the North and the South, pyrotechnic action also under the supervision of Jack Little, who had been in charge of the explosive effects for Metro’s drama of the Great War, The Big Parade. Little, it was said, ran forty thousand feet of wire at Culp Creek and personally prepared nine hundred “shots” that were either buried, concealed in trees, or fired from behind camera lines from one of three electrical command posts. As many as 150 were detonated in a single take as Southern artillery opened fire on the advancing Northerners and the site of the former Rock River Bridge became a canvas of bloodshed and fury. Then, around two o’clock on Saturday afternoon, sparks thrown off by the Comet started a brush fire along the right-of-way of the OP&E, a conflagration that eventually covered five miles.[*3]

Keaton immediately leaped into action, doffing his trousers and using them to beat back the flames while simultaneously directing the National Guardsmen from Eugene and Corvallis, working in relay, to use the coats of their uniforms as if they were blankets. A number of Confederate extras had already been dismissed for the day, and a contingent was attending a big dance in Eugene when word reached them. “I’d just started to dance,” remembered Kieth Fennell, a foot soldier, “and the announcement came over the speaker: ‘All those in the Buster Keaton movie get back to camp—there’s a forest fire.’ So we jumped in this old Model T Ford and away we went. It took us about an hour to get out there, and as we came into camp, [we could see] that [the] fire was out and Buster Keaton was entertaining the boys. He had his pants off, he had his drawers down in the back, and he had a pitchfork and was sneaking up on a little puff of smoke. Just about that time, someone in command gave the order, ‘Everybody line up,’ so we lined up and they called roll, and we were paid that night for fighting the fire.”

Four hundred Union army coats were damaged in fighting the blaze; one of Dev Jennings’ cameras, valued at $3,500, was destroyed; and six men were sent to the hospital for exhaustion, smoke inhalation, and minor burns. In all, work was delayed a day, but the company was able to pay off and release all the National Guardsmen from Eugene, Springfield, and other lower-valley towns on schedule. On midday Monday, work at Culp Creek was declared over, leaving it a deserted lumber camp. The company returned to the newly reconstituted Marietta set to stage the picture’s concluding scenes with the Cottage Grove National Guard unit standing in for the triumphant Confederate army. “When my picture ended,” said Keaton, “the South was winning, which was all right with me.”

Work in Cottage Grove was winding down when forest fires unrelated to The General made the air so smoky it became impossible to film. At the Southern Pacific depot, equipment was being loaded for shipment back to Los Angeles, and daily departures had caused the company to dwindle to just twenty in number. On August 5, Keaton surveyed the scene along Row River and made the decision to shut down production until summer rains could overwhelm and extinguish the fires. The next day, accompanied by Natalie, his parents, and Nat’s mother, Peg, he left by car for Hollywood, promising to return when the air cleared.

In the beginning, Buster Keaton rarely spoke to Marion Mack. “I had never worked with a leading man like that before,” she said. “Usually they were outgoing and chummy, but Buster just stuck to the job and his little clique, and that was all. At first I felt a little bit, I’d say, ignored or slighted, but then he got a bit more friendly as he lost some of his shyness, and he turned out to be a very nice and warm person.”

Keaton, she observed, worked hard and unwound just as fiercely while they were out on location, typically rising at six and putting in a twelve- to fourteen-hour day, often slipping in a game of baseball on the side.

“I liked Mr. Keaton, but that first month we were up there, my husband and I didn’t drink, and the troupe would meet after they got back from location and they’d have cocktails and highballs and have their dinner about nine o’clock at night. I was sort of left out of the social activity, but it was really my own fault because we just wanted to have our dinner and that was it….Sometimes those parties would go on to twelve or one o’clock. They just didn’t stop at nine or ten, not with a group like that together. They would just drink and tell stories.” She said she knew she was okay as far as Keaton was concerned when he started making her the butt of his practical jokes.

“One of the first gags he ever played on me was to have a couple of the guys grab me from behind and hang me upside down over a cake of ice as we were on the way to location on the train. I already had my makeup on, which took about an hour to do, and all of it got ruined and I was very uncomfortable, so as soon as they put me down again I went and punched Buster in the eye. It gave him such a shiner they had to stop shooting for a week. This was before I understood that he meant no harm.”

After settling into life at Cottage Grove, Marion located a secluded spot on the river and would bicycle there to swim on hot afternoons when she wasn’t required on the set. “So he and a couple of his buddies sneaked up after me one day and found where I left my clothes and tied them up in such knots that I couldn’t unravel them. And so I had to pedal back to Cottage Grove in my bathing suit, and this was quite a shocking thing to do in 1926. You simply didn’t ride a bike in your bathing suit in those days—and a wet one at that!”

Back in Hollywood, Keaton directed The General’s few interiors—his courtship of Annabelle, her rescue from the Union raiders, the scene of the Northern generals plotting their surprise attack, and a sequence in which Johnnie goes undercover in enemy territory wearing a black frock coat and stovepipe hat. “The one that gave us the most trouble,” Mack remembered, “was the night scene when Buster and I are running away from the cottage [after my rescue]. We were three weeks doing that, and even here in the studio he wanted to do it as true to life as possible, and so we did it on the back lot at night with rain and wind machines. We came in every night at about seven and stayed until maybe one, and this went on for three weeks. And each night we got soaked to the skin. It’s a wonder we didn’t catch pneumonia.”

According to her, not even all the film’s interiors were made at the Keaton studio: “Some of the supposed indoor scenes, like the one with Buster in the recruiting office, these were actually done in Cottage Grove outdoors, with fake walls but no ceiling.”

Joe Keaton, as one of the Union generals, was as much in evidence at the studio as he was in Cottage Grove, where he gave interviews, consorted with old pals like Tom Nawn and Charley Smith, and, along with such fellow cast members as Glen Cavender, Frederick Vroom, and Earl Mohan, contributed to the reciprocal entertainment during a farewell dance tendered by the locals at the town armory. “Joe?” responded Ronald Gilstrap when asked about Keaton père. “Oh boy. He had a beautiful horse, and he looked more like a general than any general I’ve ever seen. He was something else.”

In Hollywood, Alma Whitaker of the Los Angeles Times attempted to interview a reticent Buster between shots on the hot, shadeless studio lot, but even with both Roscoe Arbuckle and Lew Cody present, she was able to extract little that could be quoted directly. As the two visitors were ringing up director James Cruze and fishing for an invitation to Cruze’s Flintridge swimming pool, it fell to Joe to complete the session with grandly embellished tales of his son’s birth and early days in vaudeville.

“There is not a prouder man in the country than Papa,” Whitaker concluded. “He isn’t afraid of interviewers.”

On August 19, word reached Keaton that rains breaking a sixty-day drought had extinguished the numerous fires threatening the Umpqua National Forest, and he wired Harold Anderson of Anderson & Middleton to confirm that he and his people would be back in Cottage Grove as soon as the weather cleared. Ten days later, he stepped off the train in a downpour but appeared “rather jubilant,” since the smoke and haze had completely vanished. Traveling with him in a private railcar were Marion Mack, Gabe Gabourie, Clyde Bruckman and his wife, Bert Jackson, Fred Wright (chief mechanic and the star’s double), cast member Jimmy Bryant, Dev Jennings and his crew, and Willie Riddle, who served as Keaton’s cook and valet. All were eager to get the picture finished, but the company had to wait three days until the rain subsided and the sun began to cooperate.

Keaton’s first priority was an enhancement of the scene in which Johnnie and Annabelle set fire to the Rock River Bridge, business incorporating previous footage shot when it was still intact. With a spur logging bridge at Culp Creek standing in for the Rock River span, Johnnie piles wood on the track while Annabelle stands atop the General’s tender and helps. Accidentally, she ignites it all, leaving him stranded on the other side of the flames. Unable to get past them, he takes a flying leap over the fire just as she, in a panic, moves the engine off the bridge. He falls between the ties and plunges into the river below.

A few days later, with a section of the Keaton bridge shored up, a shot was made with Mack running the locomotive back out onto the trestle, braking it just short of calamity, and then reversing direction. It was the second time Keaton and his writers had her piloting the General all by herself, although she never got as comfortable with it as Buster did.

“I had to handle it at the top,” she said, “but there was a man down there below in case I did something wrong. But I did have to handle the brakes and do all that. I had to do that because they couldn’t photograph the man doing it.”

Toward the end of their three-week stay, the company lost another two days to weather but were able to finish the morning of September 18, allowing them to leave for Los Angeles the same day. In all, The General had been on location in Oregon nearly thirteen weeks, with scarcely a week of filming left to be done in Los Angeles. Exhilarated, Keaton had the train stopped on the way home so that he and the crew could get off and play baseball.

Buster Keaton spent the next four weeks editing and titling The General, working with the man he referred to as his cutter, J. Sherman Kell, a former conductor, appropriately enough, on the Illinois Central Railroad. Kell, whom they all called “Father Sherman” because he looked like a priest, made no editing decisions of his own. Rather, he broke the film down for easy retrieval and scraped and glued the pieces together as fast as the boss could hand them over. As far as the intertitles were concerned, Keaton wanted as few as possible.

“There was a fellow called Al Boasberg,” Mack remembered. “He was kind of a tall man with a big face, big mouth too. But I didn’t think much of his titles. (I hope he hears this.) Charles Smith was kind of nice. They wrote the titles mostly; they weren’t around too much.”

The General was ready to be screened by the middle of October, and Keaton, wary of showing a rough cut anywhere near Hollywood, arranged its initial preview in San Bernardino, a center of rail and fruit-packing operations sixty miles east of town. The new West Coast Theater seated fifteen hundred, and advance publicity in the local papers, where the title of the film was given as The Engineer, ensured a capacity turnout on a chilly Friday night. At eleven reels, Keaton knew it was impossibly long for a feature comedy—approaching two hours at the proper projection speed—but he needed to know what exactly would play before trimming the picture to seven or eight reels.

“Buster himself, present in the audience and watching tensely the reaction, surely must have been pleased with the reception,” the San Bernardino Daily Sun said in its coverage. “The one fault that might have been found with the picture was its slow beginning, but this was entirely lost sight of when the action, mixed with thrills and heart suspense, came fast and furious after the plot of the story and characters had been introduced….Any minor defects in the raw product, as shown last night, however, could not detract from the certainty that Keaton has completed his very best vehicle. The audience alternately laughed, held its breath, and was momentarily swayed with pathos, with the laughs, of course, predominating. It is this splendid mixture, in the minds of most of those who saw the picture last night, that stamps it as one of the best comedies of the screen, and a production that will do much toward advancing Keaton to the point of displacing Charlie Chaplin as the seriocomic king of the movies.”

Buoyed by the reception in the Inland Empire, Keaton spent a couple of weeks tightening the picture, then scheduled a second preview in San Jose, some 350 miles away at the southern end of San Francisco Bay. Shown the first week in November, the event was leaked in Cottage Grove by a local girl attending a San Jose teachers’ college.

“It held an audience,” Keaton confirmed. “They were interested in it—from start to finish—and there was enough laughter to satisfy.”

A few days later, the Bartell Hotel received a telegram from Gabe Gabourie indicating that Keaton, Mack, and a small company of about a dozen would return to Oregon to retake a few scenes with the General and the Comet, work that was not expected to take more than a few days.

It was around this time that Keaton also made the decision to remove the sequence, about a third of the way into the film, in which Johnnie goes undercover in Chattanooga, risking detection and leading to his discovery of the Northern generals’ plot against the South. Possibly sensing that it slowed the pace of the story, he covered the elimination with an intertitle, shaving the running time to just under eighty minutes. In that form, roughly thirty minutes shorter than the version seen in San Bernardino, he was confident enough to schedule a third preview at the Alexander Theatre in Glendale, a prominent industry showcase. Within the walls of this atmospheric Grecian garden, he would unveil The General before the most jaded of audiences. With him for the occasion would be Natalie, his parents, a smattering of pals such as Arbuckle and Cody, numerous studio personnel—Gabourie, Jennings, Bruckman, continuity girl Chrystine Francis—and, not insignificantly, Norma Talmadge and Joe Schenck, who would be getting his first look at the unlikely comedy that had cost him and his associates more than $400,000.

Anticipation was palpable in part because a dramatic photo of the Texas, lying in the water at Culp Creek, had recently appeared in the Sunday Los Angeles Times. The curtains parted on the opening title:

Joseph M. Schenck

presents

Buster Keaton

in

“THE GENERAL”

A United Artists Production

Up on-screen came the train rolling into Marietta, Johnnie Gray proudly at the throttle, basking in the admiration of the young boys as he steps down from the cab. Not only were the early minutes charming, but owing to Keaton’s passion for authenticity they had the look of a true period document. Five minutes in, with war imminent, the mood darkens as Johnnie attempts to enlist and is repeatedly rejected.

“If you lose this war,” he warns them, “don’t blame me.”

From an eyewitness account, The General clicked 100 percent with the audience that night.

“Every gag in Buster’s Cottage Grove comedy registered,” wrote Bert Bates, a native of nearby Roseburg then working in Hollywood. “The picture has laughs galore and will set a mark for Chaplin and the rest of the top-notch comedians to shoot at….When the famous bridge crash scene flickered across the screen it obtained all the thrills hoped for, and [for] the first time in many moons we witnessed an audience applauding and whooping when the Confederate army had the Union soldiers in full retreat.”

At the fade, Johnnie is issued the uniform he never thought he’d get and, as Annabelle runs to him, a Confederate general gives the order: “Enlist the lieutenant.”

A sergeant dips his pen and asks, “Occupation?”

Johnnie puffs his chest. “Soldier,” he responds.

The audience was clapping as the lights came up, reflexively at first, and then, as the full realization of what they had just witnessed sank in, their applause intensified and grew more clamorous until Keaton found himself at the center of a thunderous ovation. Some stood, turning and facing him, and within moments the entire house had joined them, up on their feet and cheering. It was an extraordinary demonstration, virtually unheard of for a preview audience. Joe Schenck beamed and said it was undoubtedly the greatest comedy Keaton had ever made. It should earn, he predicted, a million dollars for United Artists. And with that, Buster Keaton knew beyond all doubt that he had created a masterpiece.