Work and unemployment in contemporary Britain

The main issue in the current recession is the lack of demand. Unemployment has not risen because people have chosen to be unemployed. Unemployment is largely involuntary. The reserve army of the unemployed is a conscript army not a volunteer army. Unemployment makes people unhappy. It lowers the happiness of the people who are unemployed but also lowers the happiness of everyone else.

(Bell and Blanchflower 2009)

Introduction

In the previous two chapters, we largely focused on the period beginning in the 1960s and ending in the 1980s, examining changes in young people’s experiences of work and the impact of the significant rise in youth unemployment in the early part of that decade. We argued that the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 and her government’s embrace of a neo-liberal agenda led to significant changes in the ways in which the debate on youth (un)employment was framed, and the policies adopted, which set the scene for that decade and beyond.

Following the 1980s recession, unemployment rates did not return to pre-recession levels for 10 years (Spence 2011); rates peaked in 1984 and declined relatively steadily until a further recession in the early 1990s led to another upward turn. Young people’s experiences from the 1980s onwards were shaped by the expansion of educational opportunities and by growing expectations regarding the length of participation. As a result, employment rates among young people continued to fall from the mid-1990s to the present day, especially among 16- and 17-year-olds. These changes in patterns of participation, and the associated rise in qualification profiles, had an impact on young people’s expectations.

Job creation in the aftermath of the 1980s recession, and again following the 1990s recession, continued to involve a shift from the manufacturing to the service sector and involved a further loss of traditional apprenticeships and the introduction of what were referred to as ‘modern apprenticeships’. With an increase in qualifications among young people and a decline in industrial employment, those leaving education at the minimum age with relatively poor credentials faced difficulties in times of growth as well as in times of contraction.

We begin this chapter by examining changes in employment opportunities from the early 1990s to the present day, looking at trends and highlighting the extent that different groups were affected by these changes. This is followed by a discussion of changing patterns of unemployment in the 1990s recession and the Great Recession and in their aftermath. Here, we also outline the new measures introduced to serve those experiencing unemployment and discuss the changing principles that underpin policy development.

Changing structures of opportunity

Since the 1980s recession, governments in the United Kingdom and in other developed countries have encouraged increased participation in the upper secondary school and in tertiary education. These policies have been successful to the extent that there has been a more or less continual growth in educational participation and, across the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, very few young people now leave without completing upper secondary education. Higher education has also been transformed from an elite to a mass experience.

While national governments have often promoted increased educational participation on the grounds that a more educated population is believed to enhance economic competitiveness, from a young person’s perspective an awareness that unqualified leavers have poor employment prospects has encouraged young people to take shelter in education: a discouraged worker effect.

In the United Kingdom, between 1984 and 2013, full-time educational participation among 16- to 24-year-olds increased from 1.42 million to 3.03 million (despite the fact that the overall youth population fell by a million over the same period) (ONS 2014). As a result, young people in the labour market in the Great Recession were better educated than in the previous two recessions: compared to 1993, the number of 16- to 24-year-olds who were graduates had doubled (Bell and Blanchflower 2009). Consequently, the number of young people in employment has fallen: whereas in 1992 nearly one in two 16- and 17-year-olds (48.4 per cent) were in employment, by 2011 less than one in four 16- and 17-year-olds (23.5 per cent) held any form of employment (Bivand et al. 2011; Spence 2011).

On a societal level, educational policies have helped limit unemployment by reducing the numbers of young people exposed to the labour market. On an individual level, time spent in education decreases the likelihood of unemployment and can open up economic and social horizons. As Bivand and colleagues (2011) note, employers primarily focus recruitment on young people with higher qualifications. Education is also linked to healthier lifestyles and a more positive sense of well-being (Baum et al. 2013).

A college education does not carry a guarantee of a good life or even of financial security. But the evidence is overwhelming that for most people, education beyond high school is a prerequisite for a secure lifestyle and significantly improves the probabilities of employment and a stable career with a positive earnings trajectory. It also provides tools that help people to live healthier and more satisfying lives, to participate actively in civil society, and to create opportunities for their children.

(Baum et al. 2013: 7)

While education provides advantages to the individual as well as benefits to the state in terms of reduced welfare benefits and increased tax revenues, on the negative side, the increase in qualified school and university leavers has fuelled a process of qualification inflation, making it much more difficult for qualified young people to enter high-skill positions. As a result, young people may incur significant debts without securing access to enhanced earnings or stimulating jobs.

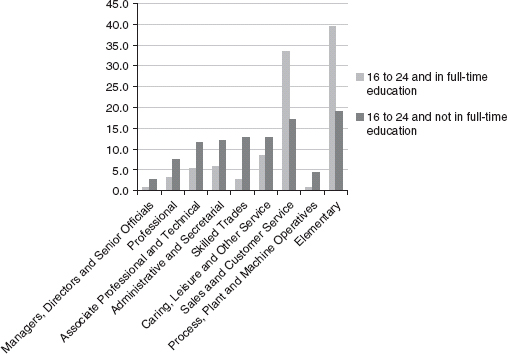

Although young people today have better qualifications than they did in the 1980s or 1990s recessions, they are still heavily concentrated in low-skill sectors of the economy. Among 16- to 24-year-olds, more than seven in ten work in elementary occupations, such as waitressing and catering assistants, and sales and customer services (ONS 2014). With many young people in this age group being in full-time education, for some the jobs they hold will be regarded as temporary, and there will be an expectation of higher-skilled occupations on completing their education. If the occupational distribution is confined to those who have left full-time education, the range of jobs they hold is more varied, although still skewed towards the low-skilled occupations (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 The occupational distribution of young people (excluding students), United Kingdom, 2013

Source: Derived from figures presented in ONS 2014.

The overall distribution of jobs for young people has been shaped by the continued decline of the manufacturing sector (which declined by 17.2 per cent between 1979 and 2010) and the continued growth of the service sector (which grew by 21.5 per cent over the same period) (Spence 2011), which has tended to involve a growth of low-skill, low-pay occupations.

Indeed, drawing on information from the UK Labour Force Surveys from 1979 to 1999, Goos and Manning (2007) argued that trends showed a growth in what they referred to as ‘lousy jobs’ over ‘lovely jobs’; lousy jobs being defined as those with low median wages such as care workers. Replicating Goos and Mannings’ analysis for the years 2002 to 2008, Bell and Blanchflower (2009) found both a growth in ‘lovely’ jobs and a modest growth of ‘lousy’ jobs with a significant decline in jobs in the middle ranges (sometimes referred to as the hourglass economy), as did Sissons (2011). Focusing on occupational change among 16- to 24-year-olds, Bell and Blanchflower (2009) also found a heavy concentration of young people in ‘lousy’ jobs in the lowest earnings decile.

In an economy where there are concentrations of opportunities at the top and bottom ends of the labour market and a shortage of jobs in the middle ranges, and where young people most frequently enter the labour market at the bottom end, there can be great difficulties in achieving the long-range mobility necessary to move from ‘lousy’ to ‘lovely’ jobs (Bell and Blanchflower 2009). Polarised opportunity structures can be difficult to traverse and may trap qualified young people in unskilled sectors of the economy.

This is a particularly vexed issue as we have an expansion of well-qualified young people, many of whom hold university degrees, in an economy where much expansion is at the lower end of the skill spectrum. In the post-recession United Kingdom, with political sensitivities about the extent to which austerity measures are helping promote economic growth, the government has been keen to highlight the creation of new jobs. At the same time, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) has shown that only six in ten new jobs are employee positions (the remainder involving self-employment, unpaid family work and so on), while three in ten new jobs are part-time (TUC 2013). Indeed, between summer 2010 and the end of 2012, nearly eight in ten new jobs were in low-paid industries1 (77 per cent) (TUC 2013).

As a consequence, there has been an increase in the number of young people working in jobs for which they are over-qualified. Poor job prospects and qualification inflation have encouraged young people to remain in education in the hope that, in the long term, they can access interesting jobs in the more secure sectors of the labour market. Yet, the evidence shows that many graduates are failing to get a foothold in the graduate labour market. With an increase in the number of graduates without a corresponding increase in graduate jobs, it has been estimated that the United Kingdom will have a surplus of at least 50,000 graduates a year (Birchall 2009).

In the United Kingdom, figures from the Labour Force Survey show that only a quarter of graduates earned more than the overall average, while a similar proportion received below average wages (Byrnin 2013). In the United Kingdom 6 months after graduation, at least four in ten graduates are in low-skill forms of employment, and 3.5 years after graduation one in four remain in low-skill jobs (Mosca and Wright 2011).

The expansion of part-time employment among young people has fuelled a growth in underemployment under which employees who would like to work full time have little option but to accept part-time jobs. In the United Kingdom, as in much of Europe, there is concern about the rise in the number of young people holding part-time jobs, or even juggling a number of part-time jobs, when they would really like a full-time job. These young workers, who are more prevalent in the United Kingdom than the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average (Bell and Blanchflower 2009), are often overlooked in policy terms, and some struggle economically.

As we saw in Chapter 2, part-time working for young people, which was extremely rare in the 1960s and 1970s, started to become more common in the 1980s, although it remained a minority experience. However, during the 1990s there was a significant increase in part-time working among young people; in 1996, for example, three-quarters of those who found jobs during the winter went into part-time work. Walker, writing in 1997, argued that ‘almost the entire net gain in employment since 1990 came from part-time jobs’ (1997: 14).

Research by the TUC (2012) has shown that since the start of the recession, underemployment has increased by a million; an increase of 42 per cent. Moreover, they argue that young people are almost twice as likely to be underemployed, with one in five young people affected. Bell and Blanchflower (2013) compared the hours that people say they would like to be able to work with those they actually work; they estimate that in the United Kingdom, underemployment among 16- to 24-year-olds stands at 30 per cent. Figures from the Labour Force Survey between the first quarter of 2008 and the third quarter of 2009 show a fall of 4 per cent in hours worked among those in employment (Spence 2011).

Campbell (2015) uses the term ‘time-related underemployment’ to describe the increasingly prevalent phenomenon whereby people who wish for full-time jobs hold part-time jobs and are unable to secure the hours they need to secure the desired standard of living. Using figures from the Australian Labour Force Survey he shows that while, in 2015, unemployment among 15- to 24-year-olds stood at 12.9 per cent, underemployment had reached 16.1 per cent.

While there has been a long-running debate about whether young people’s wage levels effectively price them out of the jobs market, Bell and Blanchflower (2009) suggest that much of the evidence is dated and comes from an era where trade unions had more influence on wage rates. Indeed, youth wages have been in decline for well over a decade, and there is a lack of contemporary data suggesting that young people’s wage rates are pricing them out if the job market. Indeed, young people and older workers tend not to compete directly with each other for jobs, as ‘young people are rarely seen as good substitutes for older workers (or vice versa) and the formal evidence, where it exists, tends to show that replacing one kind of worker with another, according to age, is limited’ (O’Higgins 2001: 17).

Trends in (un)employment

In the previous chapter, we commented on youth unemployment in the 1980s recession and its aftermath. After a peak of 1.25 million in the early 1980s, youth unemployment fell fairly sharply until the onset of the 1990s recession. The 1990s recession involved a much lower peak and a more rapid recovery (Bivand et al. 2011). While the years between the mid-1990s and the 2008−9 recession involved relatively low levels of youth unemployment, Bivand and colleagues point out that over the last two decades youth unemployment has never fallen below half a million and that a rise was evident well before the 2008−9 recession.

The period beginning in the mid-1980s and extending to the onset of the Great Recession has been referred to by economists as the ‘Great Moderation’ (Stock and Watson 2002). This period was characterised by a relative stability in business cycles involving low levels of volatility due to a lack of fiscal shocks and stable commodity prices. Gordon Brown referred to it as ‘the end of the boom and bust economy’ in which fluctuations in employment and unemployment rates were much reduced. However, while one would expect the ‘Great Moderation’ to provide employers with greater incentives to invest in human capital, over the period there was a growth in temporary and part-time employment (Ćorić 2011). One of the reasons for the growth in employment insecurity during a period when the economy lacked the levels of volatility that characterised the 1970s and early 1980s can be linked to the ongoing decline of manufacturing industry and the growth of the service sector. While modern manufacturing industry requires investment in task-specific skills, the service sector, with its demand for soft skills, may require less investment in skills and frequently has peaks and troughs in demand that steer employers towards part-time hours and flexible contracts.

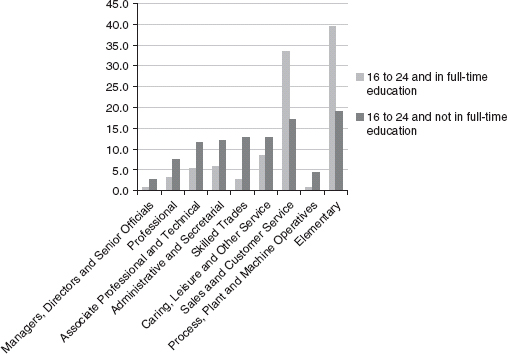

This period of low volatility came to an abrupt end with the global shock waves linked to the sub-prime loan crisis in the United States and the collapse of institutions such as Lehman Brothers in the autumn of 2008. Young people below the age of 18 were most affected by the 2008−9 recession; whereas one in four were unemployed in the first quarter of 2008, in 2011 almost four in ten were unemployed. Over the same period, unemployment among 18- to 24-year-olds rose from just over 12 per cent to almost 18 per cent (Figure 4.2). The peaks in unemployment associated with the 2008−9 recession were very similar to those recorded in the 1980s recession (ONS 2014) and, unlike the 1990s recession, involved an upwards drift that continued well after the recession formally ended. As Bivand and colleagues argue, ‘so far, for young people this recession has more in common with the 1980s, with a prolonged period of high unemployment and rising long-term unemployment’ (2011: 4).

Figure 4.2 Unemployment rates, by age

Source: Derived from figures collected by the Labour Force Survey (various).

Long-term unemployment among young people has always been a cause for concern, and many activation programmes have specifically targeted those who have been unemployed for some time. While long-term youth unemployment among 16- to 24-year-olds fell from a peak of over a quarter of a million in the 1990s recession to a low of 55,000 in 2002, it had doubled (to 110,000 in 2007) immediately before the recession and continued to rise throughout the recession, crossing the quarter-million mark again in 2011 (Bivand et al. 2011). Around a quarter of young people who were unemployed at this time had been workless for over a year (Bivand et al. 2011).

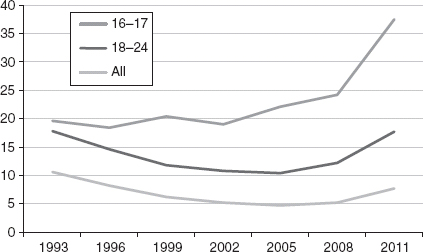

Levels of youth unemployment, and particularly long-term unemployment, in the United Kingdom have remained stubbornly high in the post-recession environment; however, the same is true in other European countries. Overall, the United Kingdom falls slightly below the overall EU average for youth unemployment, although of course the average is strongly influenced by the extremes of several southern European countries. In 2013, in Greece and Spain almost six in ten young people were unemployed, compared to around one in five in the United Kingdom (Figure 4.3). In contrast, Germany and Austria had youth unemployment rates of less than 10 per cent, largely as a result of the maintenance of a strong system of vocational training and long-established apprenticeships set within a highly regulated labour market.

Figure 4.3 Youth unemployment rates, 2013 (third quarter)

Source: Derived from Eurostat figures presented in ONS 2014.

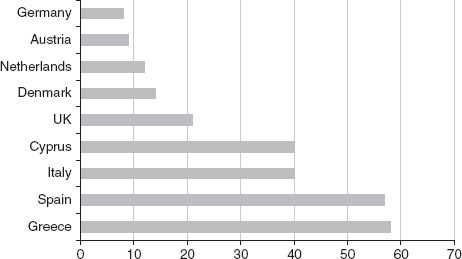

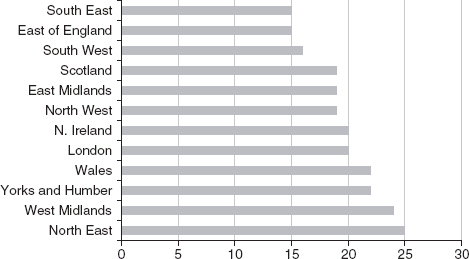

There are also strong regional variations in youth unemployment rates within the United Kingdom. With regional economies affected by their industrial make-up and susceptible in different ways to trade cycles and global economic trends, the historic surveys that we examined in Chapter 3 drew on regions that were differentially affected by the 1980s recession and, as a consequence, levels of youth unemployment covered a broad spectrum: ranging, among Roberts’s 17- and 18-year-olds, from 41 per cent in Liverpool to 8 per cent in Chelmsford (Roberts et al. 1986). In 2013, one in five or more 16- to 24-year-olds were unemployed in the Northeast, West Midlands, Yorkshire and Humberside, Wales, Northern Ireland and London, unemployment rates were up to 10 percentage points lower in the East of England and the Southeast (ONS 2014) (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 Unemployment rates among 16- to 24-year-olds by region

Source: Derived from ONS 2014.

While labour market statistics provide a clear overview of trends and show the extent to which young people suffer through changing opportunity structures and economic upheavals, less visible are shifting interpretations of the causes and consequences of youth unemployment. In particular, throughout the 1990s the Thatcher legacy continued to colour both attitudes and policies towards the unemployed (especially young unemployed). Despite clear evidence that youth unemployment was primarily caused by a deficit in demand, by skill mismatches and by spatial unevenness in opportunities, politicians frequently suggested that young people were a major part of the problem. Indeed, what we referred to as the ‘punitive turn’, which was enshrined legislatively in the early 1980s, continued to shape unemployment policy through the 1990s and to the present day. Governed under a regime of intolerance, young people are increasingly ‘subject to suspicion, scrutiny and assessment combined with compulsory divulgence and attendance, training and other exercises to become “job-ready” all backed up with threats of sanction’ (Boland and Griffin 2015).

The consequences of unemployment

While the psychological costs of unemployment are clearly documented, with strong evidence of a causal link between unemployment and psychological distress, reduced self-esteem and a decline in life satisfaction (e.g. Banks and Ullah 1988; West and Sweeting 1996), policy tends to be underpinned by a different set of assumptions. Here, young people are cast not as victims of circumstances largely beyond their control, but either as misguided individuals who have failed to take the appropriate steps to secure employment or as work-shy transgressors who are playing the system.

Interpretations that rest on a premise of deficient labour supply are the foundation upon which most work activation and skill development programmes are built. For that very reason, few are effective (Furlong and McNeish 2000). Throughout the 1990s, a number of new programmes were introduced. For young people the most significant landmarks were the introduction of Youth Training (YT) (launched in 1993 to replace the Youth Training Scheme (YTS)); Modern Apprenticeships and Accelerated Modern Apprenticeships (introduced in 1996) to cater, respectively, for 16- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 19-year-olds; and the New Deal for Young People (1998), targeting 18- to 24-year-olds unemployed for 6 months or more.

Each of these programmes placed an increased emphasis on skill development, while other trends involved contracting provision for the long-term unemployed out to the private and third sectors and a greater tendency to underpin provision with the threat of benefit sanctions for those who failed to participate. For example, Workwise, a 4-week intensive programme aimed at 18- to 24-year-olds who had been without work for a year, imposed a 40 per cent reduction in Income Support benefit for anyone failing to attend. Similarly, 1-2-1, a series of structured interviews for the same client group, was able to use full benefit suspension in the case of non-compliance.

YT (a re-packaged variant of YTS) guaranteed places for 16- to 17-year-olds, but, given the withdrawal of income support for most young people, it was only through accepting a placement that young people without a job had access to any form of financial support. YT aimed to provide better quality training than previous schemes and promised to significantly increase the numbers gaining level 2 and 3 qualifications. With an increased tendency for young people to complete upper secondary education, more places were provided for the 18-plus age group.

However, from the 1972 Training Opportunities Programme through its various incarnations, such as the Youth Opportunities Programme, the YTS and the New Deal for Young People, schemes for young people who encounter a period of unemployment have been continually criticised, mainly on account of low-quality training, poor job placement rates and a failure to convince young people of the alleged benefits of participation. YT was no exception. YT was criticised for failing to honour its guarantee to make places available to eligible 16- to 17-year-olds in a timely fashion as well as for a poor record in job placement and improved qualifications. Indeed, a survey conducted in 1995 showed that up to 60 per cent of young people who participated in the programme had no qualifications on leaving (Independent 1995).

Introduced under John Major’s Conservative government, Modern Apprenticeships were another attempt to provide better quality training and to address a perceived deficit in technician and intermediate level qualifications. With the programme aimed at bringing 16- to 24-year-olds up to National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) level 3 qualifications, Fuller and Unwin have argued that ‘the use of the term “apprenticeship” was a deliberate attempt to set the new programme aside from existing “youth training” schemes which had struggled to shake off an image of low quality’ (2013: 8).

Comparing Modern Apprenticeships with German apprenticeships, Ryan and Unwin (2001) argued that Modern Apprenticeships came closer to YT than to the German model. They argued that in the UK programme, rates of completion were relatively poor, as was the breadth and depth of training. Given that Modern Apprenticeships were supposedly about upskilling to NVQ level 3, only one in two leavers attained that level of qualification. Acknowledging some improvement over time, Ryan and Unwin nevertheless argued that ‘Modern Apprenticeship activity was biased towards short, low-cost programmes and skills not in short supply, particularly in the service sector’ (2001: 108). While echoing concerns about the poor-quality training offered to many modern apprentices, Fuller and Unwin (2013) also voiced concerns about gender segregation. While the overall uptake between males and females was relatively balanced, industries such as health and social care and customer service were very heavily skewed towards females (86 per cent and 69 per cent, respectively), while engineering and construction were almost exclusively male (recruiting 3 per cent and 2 per cent females, respectively).

Modern Apprenticeships ran alongside YT rather than replacing it, with the former able to recruit young people with the strongest qualifications. While from the outset youth training schemes had always been stratified between high- and low-quality forms of delivery, Modern Apprenticeships took these divisions to a new level. As Maclagan argued, Modern Apprenticeships offer ‘some young people high quality opportunities by implicitly devaluing or marginalising what is available for the less favoured’ (1996: 16).

The New Deal for Young People, launched in 1998, was the flagship offering of the incoming Blair government. Upholding the workfare approach to benefits, the New Deal guaranteed a place for all young people who had been unemployed for 6 months and, following a period of assessment and tailored support through a personal advisor, offered the young person the (mandatory) ‘option’ of

•a subsidised job placement for up to 6 months;

•a place on a full-time course of education or training lasting up to 12 months;

•a work placement with the environmental task force for up to 6 months; or

•a work placement with the community task force lasting up to 6 months.

Those who refused one of these options were sanctioned by withdrawal of their jobseekers (unemployment) benefits, while those who participated were not paid a wage but received an allowance of the equivalent of jobseekers benefit. In addition, young people on the environment or community task forces received an extra £15 per week, while the employers of those undertaking job placements were provided with a subsidy of £60 per week as well as £750 to cover any training costs.

While some evaluations of the New Deal (e.g. Riley and Young 2000) were very positive, highlighting a significant reduction in long-term youth unemployment, others were less complimentary. Myck (2002), for example, argued that unemployment was falling anyway, and groups who were ineligible for the New Deal also experienced reduced unemployment. Others argued that while there was a reduction in long-term unemployment, which may or may not have been linked to the New Deal, as many as one in five of those who passed through the scheme entered jobs lasting less than 13 weeks, and a third of those participating in 2007 had past experience of the programme and were effectively being recycled (Bivand et al. 2011), offering the private sector fresh opportunities to profit from their failure to provide young people with high-level skills.

Launched in 2011, the current flagship scheme is the Work Programme. Contracted out to private and third sector organisations, the Work Programme operates on a payment by results basis which has led to accusations that, driven by the profit motive, providers are focusing on clients who are regarded as easiest to place while marginalising those with deep-seated issues. Like its predecessors, the Work Programme recruits participants under threat of loss of benefit, being mandatory for 18- to 24-year-olds who have been unemployed for 9 months.

The Work Programme has come in for much criticism due to its abysmal rates of job placement: in its first year of operation, of the 785,000 people who passed through the scheme, just 2.3 per cent subsequently held a job for 6 months or more (Murray 2012). Indeed, it has been argued that ‘more people will have been sanctioned by the Work Programme than properly employed through it’ (Richard Whittell, quoted in the Guardian, Boffey 30 June 2012).

The jeopardisation of labour as the new normality

The period beginning in the early 1990s and extending to the present day has witnessed the acceleration of trends already evident in the 1970s and 1980s, such as the further decline in manufacturing industry and growth in services, and an increase in part-time and temporary forms of employment, set against the backdrop of an increasingly educated workforce. In the modern hourglass economy, opportunities are increasingly polarised.

While it is easy to put forward explanations for employment insecurity that focus on new patterns of demand and the ways in which employers seek to maintain or enhance profitability by finding novel ways of reducing wage costs, these interpretations are partial. In an economy dominated by a service sector where investment in hard skills is relatively low, it is easy to see how employers come to regard labour as a disposable commodity. Indeed, in the dog-eat-dog world of modern capitalism, labour conditions deteriorate as employers engage in a race to the bottom. Many of the so-called success stories of the modern service economy are ones that have attracted criticism for their employment policies and labour strategies; for example, Uber, Deliveroo, Hermes and Sports Direct.

Yet in all this, government has a role to play and has a responsibility for setting the framework in which firms compete. In the United Kingdom, as in many other advanced societies, governments of left, right and centre have largely accepted the new conditions and helped embed what Castel refers to as the ‘jeopardization of labor’, of which ‘unemployment is only the most visible manifestation of a profound transformation in the larger state of employment’ (2003: 380). For Castel, as well as for ourselves, the stratification between the ‘protected sectors and vulnerable workers’ (2003: 329) can be traced back to the early 1970s.

Through the various interventions that we have described in this and the preceding chapters, UK governments have been sensitive to the potential political fallout generated by high levels of youth unemployment, but they have never displayed the will to invest in high-quality training to provide the sort of workforce that will attract inwards investment by high-tech multinationals. Whereas Germany, Austria and Switzerland have maintained a high-quality system of apprenticeships, and while the Asian tiger economies, such as Singapore, have invested heavily in education and skill development, the United Kingdom has maintained what Ashton and colleagues have referred to as a ‘low skill equilibrium’: ‘reinforcing a national system of training which is inappropriate for an advanced industrial society’ (1990: 201).

The ‘jeopardization of labor’ has also been accelerated by the abdication of the state from the sphere of labour regulation, through the privatisation of so-called activation measures and through the lens of suspicion with which it views youth. In terms of regulation, old legislative protections have been stripped away, while there has been a failure to legislate to protect workers exposed to new conditions, such as zero hours contracts. Of course, one could argue that it is in the short-term political interests of governments to ignore the increase in casualisation and the growth of part-time working: like those who remain in education, young people in precarious jobs are not claiming benefits and not inflating the politically sensitive unemployment figures.

Privatisation of training for young people who experience unemployment has led to the development of a highly profitable unemployment industry, which through recycling is able to profit through a failure to place young people in stable jobs. Government tolerance (and direct funding) of a scheme like the Work Programme, with its 2 per cent ‘success rate’, shows how little the government is concerned about quality training for young people. Finally, an approach to young people who suffer the misfortune of becoming unemployed that regards them with suspicion, as ‘wasters’ to be battered into submission by a punitive and unsympathetic system, is at best counterproductive. It can force people to take up useless work experience programmes and reduce their ability to engage in effective job search activities.

In contemporary capitalist societies, even outside periods of recession, there are never enough jobs for all who want them, and many of those in jobs will find themselves with insufficient hours and with wages that are too low to maintain a decent standard of living. With a tradition of focusing on unemployment as one of the most visible manifestations of marginalisation, governments of all persuasions have helped sustain a discourse in which individuals are blamed for their predicament and treated with suspicion as work-shy parasites, thus justifying a punitive approach to benefit eligibility. These processes greatly impact on young people, as they are in transition and, therefore, more likely than older age groups to find themselves out of work or working in insecure forms of employment.

As Castel reminds us, the focus on unemployment and the use of terms such as marginalisation can be misleading ‘for it displaces to the margins of society what is really something at its very heart’ (2003: 367). In many parts of the global North, the jeopardised sector represents the new reality for young people. Within this sector, recurrent unemployment is commonplace, while employment lacks security. There is still room for some in the shrinking secure sector, although places are largely reserved for those whose parents are rich in cultural and economic capital. In the next chapter, we present some new analysis to highlight the condition of young people in the contemporary United Kingdom.

Note

1Low-paid industries are defined by the TUC as industries where average gross hourly pay falls below the 25th percentile (£7.95).