Binary oppositions … are well suited to exaggerating differences, confounding description and prescription, and setting up overburdened dualisms that erase continuities, underplay contingency, and overestimate the internal coherence of social forms.

(Wacquant, 2008: 233−234)

Introduction

In the post-recession United Kingdom, conditions that can be linked to the policies of austerity followed by the Coalition government up to 2015 and the Conservative government from May 2015 mean that many young people’s lives are characterised by hardship and uncertainty. Yet, to an extent, uncertainty has always been central to the experience of being a young person: even in times of prosperity, outcomes and destinations were unpredictable for large sections of the young population. Young people inhabit a zone where their futures are represented as hopes or fears; and research conducted long before the recent recession has shown how even those from very privileged families worry about their futures (e.g. Walkerdine et al. 2001).

Of course, outcomes become even more uncertain in times of economic instability. In such times, young people have difficulty securing work may be forced to work in jobs that they regard as unsuited to their skills and qualifications or may prolong their educational careers as a way of sheltering themselves from the real or imagined turbulence of a tightening labour market. In such circumstances, young people may regard their current situation as temporary, while worrying about the unpredictability of future prospects.

Youth and young adulthood are temporary phases in the life course, and levels of employment continually rise and fall, making predictions difficult. When good times prevail, periods of uncertainty may be relatively brief, while in hard times they may be extended. Following the early 1980s recession there was a debate among youth sociologists, led by David Ashton and colleagues (1990) and David Raffe (1986), which focused on the question of whether we were living through a period of temporary turmoil or whether we had crossed a watershed in which opportunities had been permanently transformed in ways that were unfavourable to both current and future generations.

On one side of the debate, Ashton and colleagues were arguing that the increase in youth unemployment was a consequence of long-term processes of change within capitalist economies; they saw high rates of unemployment as being a permanent feature of the new post-recession world order. They argued that

we are currently witnessing a radical restructuring of the labour market in general and the youth labour market in particular. [Leading to] fundamental underlying structural changes which have produced a mismatch between the supply flow of young people entering the labour market and the demands of employers.

(Ashton et al. 1990: 2)

Raffe (1986), on the other side, argued that the increase in unemployment was linked to the recession and was, therefore, a temporary phenomenon. In a sense, both arguments contained some truth: Raffe was right to argue that unemployment rates would fall significantly in the post-recession era, but Ashton and colleagues were correct to argue that there were far-reaching processes of change that would continue to impact on young people following the recession.

Through an analysis of the UK Household Longitudinal Study (known as Understanding Society) data, in this chapter we further explore patterns of insecurity in the contemporary UK labour market and its implications for the social condition of young people.

Insecurity and flexibility

One of the questions that youth researchers are asking today again relates to the extent to which changes that we can observe now, notably the growth of temporary, part-time and atypical forms of employment, mark the contours of a future marked by lifetime uncertainty and hardship for large sections of the population. Guy Standing (2011) has been particularly vocal in his view of a future marked by growing precarity. In a similar vein, sociologists such as Ulrich Beck (2000) have argued that Western labour markets are moving closer to those represented by developing countries such as Brazil, where job insecurity is ubiquitous. These views are not without their merits: while accelerated by the recession, it is clear that the trend towards more precarious forms of working predated the recession (e.g. Furlong and Kelly 2005). Such conditions are not the preserve of a poorly skilled underclass; they have become common among young people from a wide range of social classes and from across the attainment spectrum. The benefits to business of a shift towards greater use of temporary and non-traditional employment contracts are clear:

For businesses, this creates ‘flexibility’. Fixed (or sticky) labour costs can be rendered variable; workplace discipline and control can be exercised individually (and indeed daily); some of the risks and costs associated with demand fluctuations can be externalised to the workforce; employment relationships can be initiated and terminated at will.

(Theodore and Peck 2014: 26)

While some of the most influential names in sociology have argued that increased insecurity of labour has to be regarded as one of the core components of late modernity (e.g. Giddens 1990; Beck 1992; Sennett 1998; Bauman 2000), others have argued that theory is running ahead of empirical evidence. In an important contribution to the debate, Fevre (2007) is quite clear in his view that there is a lack of evidence to support the claim that employment insecurity has increased in either the United Kingdom or the United States. However, Fevre (2007) employs a narrow definition of insecurity, although he does explore both objective and subjective dimensions.1 On the surface, his argument looks plausible; however, he defines insecurity in a way that leads to the exclusion of work situations that are important for young people, notably part-time jobs and training schemes, which tend to regarded as temporary even if the contractual situation is secure. Indeed, when Castel (2003) speaks of the ‘jeopardization of labor’, his focus is not just about temporary contracts but refers to atypical work which may be fixed-term, but may also be part-time or ‘offered’ under an activation programme. For young people, underemployment, in the sense of wanting more hours than are available or being employed in occupations that are way beneath what they would expect on the basis of their qualifications, may also be regarded as features of insecurity: while these folk may have permanent contracts, they probably regard their status as temporary, or at least hope that it is.

MacDonald (2016) describes a broad variety of approaches to insecurity employed by researchers that include a wide range of factors that go beyond impermanence and include a lack of social benefits, low wages, health risks, and being ‘over-qualified’ for a job. Reviewing young people’s situations across Europe, MacDonald suggests that in the United Kingdom, ‘the problem was less about the prevalence of temporary work and more of over-qualification for the sorts of jobs that were available’ (2016: 158); in other words, the temporal insecurity that may be linked to the hope that a specific job is temporary and that more skilled employment will become available.

Further, defending Sennett against Fevre’s accusations that his work lacks a firm empirical foundation, Tweedie argues that a narrow focus in insecure tenure misses the point: ‘for Sennett, the harms flexible management practices cause workers stem from the destruction of routine work time’ (2013: 97) and by undermining people’s ability to construct meaningful life narratives. In the literature on youth, the unsettling effects of the changes relate not so much to contractual issues but to the desychronisation of lives with family and friends (Woodman 2012) and the reduced control over lives in a broad sense; factors that can be credited to part-time work and subjective temporality as well as to contractual insecurity.

In the United Kingdom, much recent attention has been given to one particular form of atypical employment: zero hours contracts. With a zero hours contract, employers are not obliged to offer a fixed number of weekly hours to employees, even offering them no hours at all in a particular day, week or month if that suits the business. Such contracts are not necessarily temporary in nature. It has also become clear that some major employers rely very heavily on zero hours contracts: Sports Direct employs 23,000 workers, mainly young people, and 90 per cent of them are said to be on zero hours contracts that provide no guarantees of regular work. Many workers on zero hours contracts, as well as those on more traditional part-time contracts, would prefer to work full-time hours and can be considered to be underemployed.

Standing (2011) refers to the increasing population holding fixed-term, flexible and insecure employment contracts, as well as those with part-time jobs who desire full-time employment, as the precariat. With much of the growth in jobs in the post-recession UK occurring in low-skill and insecure sectors of the economy, his line of argument has its attractions. Yet, Standing regards the precariat as a ‘class’ or as having ‘class characteristics’ (2011: 8), even recognising, as he does, that they are ‘far from being homogenous’ (2011: 12); he paints a picture of a powerless group who ‘lack a work-based identity’ (2011: 12), powerless victims robbed of agency by an all-powerful capitalist class and the governments that serve its interests.

However, there are important sources of internal differentiation that are sustained by various forms of capital which lead us to question the idea that there has been a ‘democratisation of insecurity’ (Brown et al. 2003: 108) or whether the precariat can be regarded as a class. There are crucial differences between workless young people who lack skills and qualifications and graduates working in part-time or temporary forms of employment, as Max Weber would remind us: differences that relate to the ways in which education and skills are commodities of value to be traded on the labour market. To present the precariat as a class is to suggest that an unqualified young person working on a zero hours contract flipping burgers at McDonald’s occupies a similar position to a pilot on a zero hours contract working for Ryanair. In a recent report to the European Commission, Jorens and colleagues (2015) argued that nearly one in two pilots working for low-fare European airlines were on temporary contracts, were self-employed or recruited through agencies. While job insecurity among pilots may be a cause for concern, as a group they may command relatively high wages and probably possess a strong work-based identity.

In our view Standing, disregarding Wacquant’s (2008) warning about the dangers of binary oppositions, has tended to simplify a trend that is much more nuanced than he is prepared to recognise. Here, in exploring the conditions experienced by young people in the contemporary UK labour market, we look more closely at the stratification of the labour market for young people and of the factors that determine their distribution across sectors.

Young people and segmented disadvantage

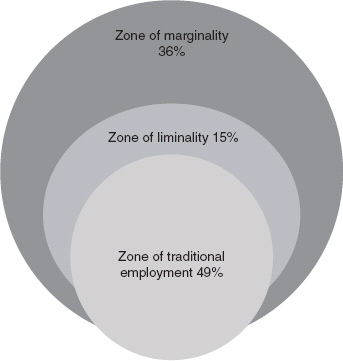

Starting from the position that all young people face uncertainties, with some clearly more vulnerable than others on account of the capitals they possess, in Chapter 3 we suggested that a series of risk zones can be identified, with placement in zones and movement between them conditioned by social, cultural and human capital and taking place within spatial horizons that give rise to different opportunity structures. The relative sizes of these zones differ over time and between places, but we would concur with Standing’s position that there has been a trend towards the growth of zones characterised by insecurity and marginalisation. These zones, which we described with reference to the 1980s in Chapter 3, are represented using contemporary data in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Zones of (in)security (2010)

Using data from the first wave of Understanding Society (2010) for 18- to 25-year-olds, the relative size of each of the zones is shown in Figure 5.1. As in Chapter 3, we defined the zone of marginality as2

•the formally unemployed and those without any paid work;

•the sick and disabled;

•those on maternity leave or caring for others;

•those on government training or work experience schemes; and

•those working fewer than 16 hours a week.3

This group accounts for 36 per cent of the population of young adults, with the formally unemployed being the largest sub-group (52 per cent of the group). The zone of marginality is skewed towards females (56 per cent vs 44 per cent), largely on account of their over-representation in caring activities. One in four of this group (26 per cent) had never held any form of paid employment.

What we define as the zone of liminality represents 15 per cent of the 18- to 25-year-old population and members are defined as

•those whose contract of employment is time limited in any way (e.g. temporary contracts, agency hires etc.); and

•those working at least 16 hours per week but less than 30.

The zone of liminality is skewed slightly towards those on temporary contracts over those working part-time hours, and the group is skewed towards females (58 per cent vs 42 per cent).

As a group who are either unemployed, in receipt of benefits or working very few hours, the marginalised group are deprived economically. Nearly eight in ten (78 per cent) had a gross income of less than £670 per month, a sum that represents 60 per cent of the gross income of a worker in an elementary service occupation (defined here as poverty wages); a further one in five (19 per cent) received between £670 and £1200, which represents 60 per cent of the UK median wage in 2010 (referred to here as the economically challenged).

Those in the zone of liminality were better off financially, although six in ten (58 per cent) received poverty wages, and a further four in ten (38 per cent) were economically challenged. While marginalised females received slightly higher levels of income than males (a figure that will be skewed by child benefits), in the zone of liminality females were worse off economically than males.

In this model, Standing would regard these two outer zones (what we refer to as the zones of liminality and marginality) as representing the ‘precariat’; we suggest that there are important lines of differentiation that justify the division that we make. Young people working very few hours, those without work or on government schemes tend to have less control over their lives than those whose conditions are insecure or who are underemployed and working between 16 and 30 hours a week. Indeed, those on benefits face punitive conditions: from 2011 they could be forced to work for 30 hours a week for 4 weeks under the threat of having their benefits stopped, a sanction that is brought to bear on those who miss or are late for appointments with their advisor or who are not deemed to be sufficiently engaged in job search activities.

An analysis by the Guardian newspaper suggests that in the year ending April 2014, one in six jobseekers were sanctioned by having their payments stopped (Butler and Malik 2015). These so-called mandated workers are expected to undertake work for the benefit of the community while continuing their job search in the reduced time available.

I worked in admin since leaving college. It’s all I’ve ever done and to be honest, it’s what I’m good at, it’s all I want to do. I lost my job at an estate agents in the recession and had to go on Jobseekers. I was asked what jobs I was looking for and I told them admin, secretarial and personal assistant work. What I’m qualified and experienced in. They sent me to work for a supermarket for four weeks. I had no choice or I’d lose my money. I finished it last week and was told there was no job at the end as I didn’t have enough ‘retail experience’. What was the fucking point of that?

(Boycott Workfare)

Mandated workers are severely constrained in that they have no choice about the type of work they do: in one well-publicised case, a graduate, Cait Reilly, who had arranged her own work experience in a museum, was forced to work stacking shelves in Poundland under threat of benefit sanction. Workers who are mandated under UK workfare policies would appear to fall into the International Labour Office’s definition of forced labour. Under the Forced Labour Convention (1930, No. 29), ratified by 177 states, forced labour is defined as ‘all work or service that is extracted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily’. A subsequent supplement to the convention (1957, No. 105) makes it clear that forced or compulsory labour is prohibited where it is used as a ‘punishment for the infringement of labour discipline’ (ILO 2014). Compared to mandated workers and others who occupy the zone of marginality, young people in the zone of liminality would appear to have greater control over their lives, with some accepting low-waged part-time or temporary work as a way of freeing themselves from reliance on a punitive welfare system.

Beyond marginality and precarity

Beyond what Standing would refer to as the precariat (and what we refer to as the zones of liminality and marginality), roughly one in two 18- to 25-year-olds were in full-time permanent employment (referred to here as the traditional zone) (49 per cent), with males being much more likely than females to be working full-time on a permanent basis (57 per cent compared to 43 per cent). Those in the traditional zone were roughly divided between those receiving more than 60 per cent of the median wage (£1,200) and the economically challenged. Adding economically challenged full-time employees to those in the zones of liminality and marginality means that around three in four 18- to 25-year-olds have to cope with trying circumstances.

With educational qualifications being a strong determinant of young people’s distribution across zones, it is clear that human capital offers some protection from liminality and marginalisation. Compared to those with higher level qualifications (A levels, degrees or equivalent), those with lower level qualifications (General Certificate of Secondary Education or lower) were around twice as likely to occupy the zone of marginality (52 per cent vs 25 per cent). While almost six in ten (58 per cent) young people with high-level qualifications were in full-time employment with permanent contracts, of those with lower level qualifications around a third (34 per cent) were similarly employed. In other words, there are still potential rewards to be gained through investment in education, even though gains are not guaranteed. In this context, it is important to be aware of a process of qualification inflation, whereby higher level qualifications become necessary to be considered for jobs that once required fairly minimal qualifications. Drawing on the UK Skills and Employment Surveys, which include workers of all ages, Gallie and colleagues argue that

The qualification requirements of jobs in Britain have moved upwards since 1986. However, the trend became even more pronounced between 2006 and 2012. Jobs requiring no qualifications on entry fell from 28% in 2006 to 23% in 2012, while jobs requiring degrees or higher rose from a fifth (20%) in 2006 to a quarter (26%) in 2012. At no time in the 1986-2012 period have falls and rises of these magnitudes been recorded.

(2014: 209)

Moreover, this process of qualification inflation has impacted on part-time employment: 63 per cent of part-time jobs required no specific qualifications in 1986, while by 2012 just 30 per cent could be secured without qualifications (Gallie et al. 2014).

Area of residence was also an important predictor of employment status (Figure 5.2). Both in labour markets characterised by low employment and those characterised by medium unemployment,4 around one in two young people were in the traditional zone, compared to just over four in ten residents (44 per cent) of high unemployment areas. In high unemployment areas, more young people occupied the marginalised zone, while the size of the zone of liminality was also slightly larger in high unemployment areas. Residential capital is important, although weaker than educational capital, just as it was in the work conducted by Ashton and colleagues and Roberts in the 1980s, which we discussed in Chapter 3.

Figure 5.2 Employment status by levels of unemployment in the local labour market

As young people are in a state of transition, over time we would expect to find movement from the zones of liminality and marginality towards more stable employment positions and see people successfully secure permanent jobs. A simple breakdown by age shows that younger age groups are more strongly clustered within the marginalised zone and the older age groups represented and more thinly represented in the traditional zone (Figure 5.3). For example, while just under one in two 18- and 19-year-olds were in marginalised positions (48 per cent), the corresponding figure for 24- and 25-year-olds was 28 per cent. While just over three (32 per cent) in ten 18- to 19-year-olds had full-time permanent jobs, nearly six in ten (58 per cent) 24- to 25-year-olds occupied such positions. However, with graduates entering the labour market from their early twenties onwards, movement from marginalised to core positions is likely to be exaggerated in this graph, as the populations in the two time periods are significantly different.

Figure 5.3 Employment status by age

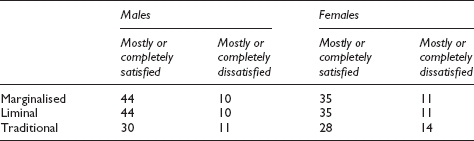

To assess levels of movement from the zones of liminality and marginality into the traditional zone, it is necessary to use a longitudinal perspective (Table 5.1). Taking those young people who were aged 20−21 at wave 1 and tracking them through to age 23−24 at wave 4, we find that more than half of those who occupied marginalised positions at wave 1 also occupied marginalised positions at wave 4 (56 per cent), one in four had moved into the traditional zone (26 per cent) while almost one in five (18 per cent) had moved into the liminal zone.

Table 5.1 Employment status of individuals at wave 4 (aged 23−24) compared to wave 1 (20−21)

Among those in the zone of liminality at wave 1, over four in ten (44 per cent) had moved into the traditional zone, while nearly one in five (18 per cent) now occupied marginalised positions: nearly four in ten (37 per cent) remained in the liminal zone. A strong majority of those in the traditional zone at wave 1 were in the same position at wave 4 (83 per cent), although 6 per cent had moved into the zone of liminality and one in ten (10 per cent) were in marginalised positions. In other words, there is clear evidence of a scarring effect whereby early disadvantages seem to colour subsequent experiences.

There are quite striking differences here between males and females. Specifically, over the four years, 45 per cent of males as compared to 10 per cent of females moved from marginalised to traditional zones, with those females who did move out of the zone of marginality being much more likely than males to move from the marginalised to the liminal zone (24 per cent vs 11 per cent). Three in ten males (75 per cent) who occupied the liminal zone at wave 1 were in full-time permanent employment at wave 4, compared to a third (32 per cent) of females. Over the period males were more likely to remain in the traditional zone (87 per cent vs 77 per cent): a move partly reflecting the number of females who were withdrawing from the labour market to care for a family.

In sum, the figures clearly show that young people (especially females) who enter disadvantaged positions in the labour market find it difficult to move into full-time permanent jobs, while the vast majority of those who manage to enter secure positions at an early stage retain their advantaged positions.

The social condition of young people in the contemporary labour market

Evidence from a wide range of countries and stretching back several decades demonstrates a clear link between job quality and psychological well-being and physical health (e.g. Banks and Ullah 1988), especially in relation to control over tasks and the ability to influence work-related decisions. Using well-validated scales developed by Warr (1990) on nationally representative data relating to all-age employees, Green and colleagues (2014) argued that between 2006 and 2012 there was a significant decline in job-related well-being. Using the same data, Gallie and colleagues (2014) show that over the same period there was an increase in job intensity (more people reporting that their job involved ‘hard work’), a (smaller) rise in the numbers reporting that they worked under pressure due to tight deadlines and, for men, an increase in the number working in ‘high strain jobs’ (jobs that involved low levels of control as well as high work intensity). Over this period, there was no change in task discretion, although the authors note that with a rise in qualification requirements over the same period they would have expected to see an increase in task discretion. Finally, Gallie and colleagues note that people’s fear of losing their jobs was higher in 2012 than in any other year covered by the surveys, ‘including 1986 when unemployment rates were very much higher’ (2014: 218).

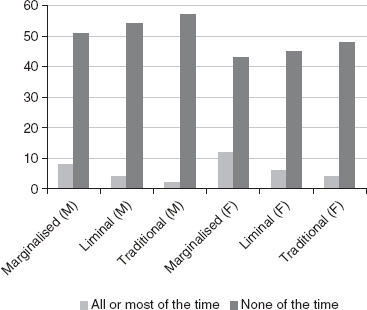

Whereas we expected to find sharp differences in reported satisfaction with current jobs between those in the traditional zone and those in the zone of liminality, very similar numbers expressed dissatisfaction with their jobs: among the males, 10 per cent of those in the zone of liminality were dissatisfied compared to 7 per cent in the traditional zone; among the females the corresponding figures were 6 per cent and 7 per cent (Figure 5.4). However, the other end of the scale, males in the traditional zone were far more likely than those in the zone of liminality to report feeling mostly or completely satisfied (53 per cent vs 39 per cent), with the corresponding difference for females being almost non-existent (57 per cent vs 56 per cent).

Figure 5.4 Gender and employment status, by satisfaction with current job

Overall satisfaction with life was relatively high irrespective of employment status, with more than one in two males and females (50 per cent and 54 per cent, respectively) saying that they were completely or mostly satisfied with life. At the other extreme, just 4 per cent of males and 3 per cent of females reported that they felt completely or mostly dissatisfied with their lives. However, for males and females, those in traditional employment were most likely to express satisfaction and least likely to express dissatisfaction, while those in marginalised positions were least likely to report satisfaction and most likely to report dissatisfaction (Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5 Gender and employment status, by whether completely satisfied with life

Overall, nearly one in two young people reported often or mostly feeling optimistic about the future (47 per cent of males and 52 per cent of females), although almost one in five said that they either rarely or never felt optimistic (17 per cent of males and 14 per cent of females). Feelings of optimism about the future were more positive among those in traditional employment, with little difference between males and females (Figure 5.6). While more than one in two traditional employees said that they often, or mostly, felt optimistic about the future, less than four in ten young people in marginalised positions felt this way. Conversely, around one in four young people in marginalised positions (25 per cent of males and 24 per cent of females) said that they never or rarely felt optimistic about the future, compared to 13 per cent of males and 14 per cent of females in traditional employment. Levels of optimism among those in the zone of liminality were closer to those in the marginalised zone than they were to those in traditional employment.

Figure 5.6 Gender and employment status, by optimism about the future

While young people are often quite resilient, it is clear that employment status can impact on subjective well-being and mental health. Asked whether they had felt downhearted and depressed over the last 4 weeks, marginalised males and females were four times more likely than those in traditional employment to reply that they always or mostly felt this way (Figure 5.7). However, to put this into perspective, even among those marginalised, one in two males (51 per cent) and more than four in ten females (43 per cent) said that they never felt downhearted and depressed (the corresponding figure among those in full-time permanent employment being, respectively, 57 per cent and 48 per cent).

Figure 5.7 Gender and employment status, by feeling downhearted and depressed over the last 4 weeks

For young people, especially those who lack significant financial obligations, overall satisfaction with life and feelings of depression may be affected by factors other than job quality or employment security: leisure, time spent with friends and family and the ability to pursue non-work-related interests may be prioritised.

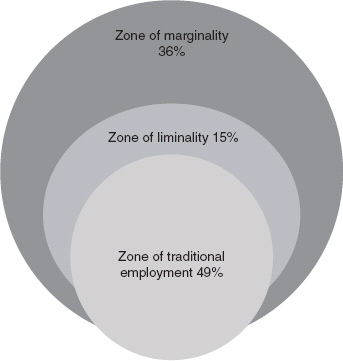

Overall, around a third of respondents said that they were mostly or completely satisfied with the amount of leisure they had, although those in traditional employment were less satisfied than the other two groups, suggesting that full-time employment had a detrimental effect on leisure time with some benefits in terms of leisure evident among those in the liminal and marginal zones (Table 5.2).

Table 5.2 Gender and employment status, by satisfaction with amount of leisure time

One of the consequences of exclusion from full-time employment relates to levels of income. Almost one in four young people in marginalised positions were completely or mostly dissatisfied with their incomes (23 per cent of males and 24 per cent of females), being around twice as likely to express dissatisfaction as compared to those in the liminal zone or in traditional employment (Table 5.3). The differences in levels of satisfaction expressed by traditional employees compared to those in the liminal zone were almost non-existent, suggesting that those in part-time and temporary forms of employment are relatively satisfied with their income (and of course, those with more than one part-time job may not suffer in terms of earnings).

Table 5.3 Gender and employment status, by satisfaction with income

Boiled frogs: the new normality?

Some commentators recognise that the trend towards an increased insecurity of employment preceded the Great Recession, while arguing that an acceleration of the trend was attributable to the economic downturn: this is a view to which we subscribe. Influential social scientists, such as Standing and Beck, are also of the view that the tendency for precarious forms of employment to grow will continue and is probably irreversible: we also accept that this is a likelihood. However, we also suggest that these trends have such deep roots that young people have gradually built the changing realities into their expectations. In other words, young people have not suddenly found themselves having to cope with a radically altered set of realities (with all of the implications for subjective adjustments and well-being which may be triggered): the metaphor of the frog placed in a pan of cold water which is heated gradually until it is cooked to death vis à vis the frog dropped in boiling water that jumps out immediately is particularly apt.

With changes having taken place very gradually, we argue that on a subjective level, transitions are often accomplished without any major shocks, in a similar manner to that highlighted by Ashton and Field (1976). In other words, today, as in the 1960s, the realities encountered more or less confirm expectations. With parents of contemporary youth likely to have experienced high levels of unemployment themselves as school leavers, it is also likely that families help reinforce the view that transitions can be difficult to accomplish and security can be elusive.

Standing’s (2011) views about the implications of contemporary labour market conditions imply that people have been taken by surprise by changing opportunity structures and are either projecting their frustrations outwardly as anger or internally in the form of subjective distress. Here, Standing refers to the four As that represent potential responses of the precariat to their suffering. These are

•anxiety, which stems from the economic uncertainty;

•anomie, as life comes to be seen as lacking meaning;

•alienation, as they lack control over their employment situations and work under conditions that are not of their choosing; and

•anger, as they realise that avenues to security are blocked and that the future is marked by relative deprivation.

It is true that, placed in situations where outcomes are unclear, young people can feel under pressure and may suffer from a decline in subjective well-being. As our earlier analysis showed, those occupying the most disadvantaged positions in the labour market tended to display the lowest satisfaction with life, tended to be least optimistic and had the poorest mental health, as measured on the General Health Questionnaire scale. At the same time, most young people were satisfied with their lives, and levels of optimism were high.

Our boiled frog hypothesis can be explained by Hall and colleagues’ (2013) description of the ways in which sets of beliefs become embedded in our assumptive worlds and accepted as common sense. While Hall and colleagues (2013) are referring to the ways in which the core tenants of neo-liberalism, the market economy, free trade and the primacy of the private sector have become embedded in our beliefs, we suggest that there are sets of assumptions about the importance of Fordist employment models that may have been regarded as part of the natural order by those coming of age in the 1960s and 1970s which are no longer part of the assumptive worlds of young people today.

In this context, Wierenga warns that ‘it is too easy to uncritically draw on paradigms that celebrate full-time work as a norm and as the measure of success’ (2009: 118, original emphasis). Indeed, the young Australians that Wierenga studied were clear in their view that ‘working is not the aim of life’ (2009: 118); she stresses the importance of ‘meaning, livelihood, connectedness, multi-dimensional lives and work-life balance’ (2009: 118). In another Australian study, Stokes argued that employment instability, what Standing would term precarity, is not necessarily regarded by contemporary youth as unfavourable: ‘many young people embrace flexibility as a way of life and view commitment to a single occupation for life as boring, or not allowing the possibility of achieving balance with the many commitments in a young person’s life’ (2012: 78).

It is true that processes of casualisation are far more advanced in Australia than in the United Kingdom (Furlong and Kelly 2005), and with employers being legally obliged to pay casual workers a ‘penalty’ wage loading, some young people may prefer to trade the entitlements that come with a full-time post (such as holiday pay and sick pay) for an hourly wage supplement in the order of 20 per cent.5

Although the Australian context is different, research in the United Kingdom has reached similar conclusions regarding young people’s attitudes towards non-permanent employment. In a study of young people in Bristol, Bradley, for example, argued that even where young people held insecure or precarious jobs, they did not necessarily regard their situations negatively and were not ‘distressed by their circumstances’ (2005: 111), and many maintained a high degree of optimism about their futures.

The new normalities that underpin the assumptions of contemporary youth can be observed right across the zones of (in)security outlined earlier in this chapter. Among those we might describe as ‘protected’, young graduates who have been able to draw on their families’ social and financial capital and have taken the advice of governments to invest in their future prosperity and security through advanced education often do not expect major pay-offs. In a study of UK graduates in their mid-twenties, Brooks and Everett found that that their respondents regarded their degrees as a ‘basic minimum’ (2009: 337) which were unlikely to open doors to rewarding careers. As one of their respondents commented on their degree, ‘it’s not so much a unique thing anymore – but without it you’re kind of a bit stuffed’ (2009: 337). For these young graduates, job insecurity following graduation was an expected part of their early careers, even in high-status fields such as law, and was not necessarily viewed negatively. One young woman, for example, argued that

I did really enjoy temping and I think it showed me what I was good at, the fact that I could get on with a variety of people … that I was very confident and capable in certain areas. It showed me things I definitely didn’t want to do’.

Young people with relatively poor qualifications and those living in areas of high unemployment who may be vulnerable tend to have an awareness of their disadvantaged position and, while they may maintain relatively high aspirations (Kintrea et al. 2015), their expectations are more realistic. Employment is often seen instrumentally, as a means to a comfortable life, rather than as a source of fulfilment. In a study of moderately qualified working-class young men, Roberts and Evans (2013) argue that their aspirations are modest and often focused on the mundane. As one of their respondents explained,

I’m not some flashy fuck, I’m not gonna sit here and say I wouldn’t like a big house and that, and a Merc or something, but it’s not likely to happen. What I want more than anything is to just be able to have my own place eventually, be able to go and see my mates after work sometimes, sometimes stay in on my own … And, um, end up living with a girl I guess.

Those who occupy the zone of liminality cannot be regarded as a homogenous group; while they may share aspects of their current work situation, this zone includes those from middle-class families who, rightly or wrongly, regard their situations as temporary, as well as those from working-class families who may experience regular periods of unemployment punctuated by occasional periods of casual work throughout their working lives. One in five young people in this zone have degrees, and some will be building up portfolios of experience as part of a strategy to enter professional careers; others may lack any control over their situations and may even occupy mandated positions. The zone of liminality is not a democratised (Brown et al. 2003) state of insecurity.

Those suffering most from contemporary conditions are the one in three that occupy the zone of marginality. While the boundary between the zones of liminality and marginality is a leaky one, with significant two-way traffic, clearly those who occupy marginalised positions tend to have least control over their lives. Young people in this zone have long been the focus of policy, and there have been numerous (largely ineffective) attempts to move them into work through training programmes, to create intermediate labour markets to provide experience and to mandate unpaid work. Policy debates about this group tend to focus on individual deficits, be they skills, qualifications or attitudes. However, the academic literature clearly shows that the problem is on the demand side of the labour market rather than the supply side. While some young people in this zone lack qualifications, many are well qualified (one in ten are graduates).

In a study of two severely deprived areas of Glasgow and Teesside (Shildrick et al. 2012), young people who were long-term unemployed displayed a desperation to work, even when they were extremely pessimistic about their chances of finding a job. As one young man put it,

if I could get a job I would stick to it and do anything I can just to keep it. I would like warehousing, like labourer, even sales assistant, just any job, cleaner. … You need a job just to grow up, more or less. If I got a job that would prove that could stand on my own two feet and things. A job isn’t just a job, it’s more than a job. It’s the future of your life.

Unlike the other two zones in our model, the zone of marginality has not become normalised, nor is it democratised. Those without qualifications, from poor families and living in areas which have weak labour markets are over-represented, and, while worklessness is not uncommon, those affected rarely lose all hope to the extent that they regard it as a normal and accepted long-term status (Shildrick et al. 2012); and the association between unemployment and a declining sense of well-being are well-documented (e.g. Warr 1990).

Looking across the zones that make up this new landscape of (in)security, there is now a widespread belief that the ability to manage life projects through the development of effective navigation skills places an increased emphasis on the importance of agency in determining outcomes. The new language of policy incorporates these beliefs through the idea of employability. Employability is presented as an ability to gain and maintain employment; the skill to navigate opportunities and sell oneself as a desirable product. However, the idea reinforces the notion that a lack of employment or a turbulent career is the product of supply side deficits and overlooks the fact that

employability will vary according to economic conditions. At times of labour shortages the long-term unemployed become ‘employable’; when jobs are in short supply they become ‘unemployable’ because there is a ready supply of better qualified job seekers willing to take low-skilled, low-waged jobs’.

(Brown et al. 2003: 110)

Conclusion

In a context where flexibilisation and insecurity have become key features of the neo-liberal landscape, and hardship and insecurity are common among young people, we must be cautious about approaches that suggest there are moves towards a democratisation of insecurity involving a growing and relatively undifferentiated ‘precariat’. Marginalisation, insecurity and risk are structured states, and human, social and cultural capital ultimately provide some protection for privileged groups. We see no merit in presenting as homogenous something that is essentially heterogeneous, indeed, it is a disservice to the truly disadvantaged (Wilson 1990) to suggest that their misfortunes are shared by a broader group who benefit from a range of resources that others are denied.

While employment conditions and prospects have deteriorated, and may well continue to deteriorate, many young people maintain their optimism and report satisfaction with their lives. While we argued that the gradual nature of the changes can be seen as confirmation of a boiled frog hypothesis, du Bois Reymond and Plug explain reactions as being part of a shift ‘away from a work ethic to what we might term a combination ethic, stressing a balance of values and priorities’ (2005: 56). Although many young people are able to ride above the turbulence of the labour market, we have argued that suffering is not uncommon, but nor is it universal. In other words, the changes we have described have consequences which extend beyond the material to the ways we engage subjectively with the world. For some young people, the importance of employment and work-based identities will be downgraded as they seek to find alternative sources of fulfilment; others will be consumed by anxieties and will suffer psychologically as they link their circumstances to their own actions rather than to external forces that are beyond their control.

Notes

1Defined by temporary contractual status, an understanding that a job was not permanent in some way, feelings of job insecurity or expectations of becoming unemployed in the next 12 months.

2There are some small differences in the ways the zones were specified in the historical and contemporary data due to the ways that different variables were defined (e.g. part-time work can only be defined as less than or more than 10 in the historical data).

3There is, inevitably, a degree of arbitrariness in deciding on an hours-based division, although those working fewer than 16 hours are unlikely to be able to sustain an above-poverty level of existence without a benefit or tax credit subsidy (and those working less than 16 hours are currently ineligible for benefits in the form of Working Tax Credits).

4Official unemployment statistics pertaining to 2011 were assigned at the level of travel-to-work areas which were then aggregated to equal thirds to represent areas characterised by high, medium and low unemployment.

5For example, an 18-year-old working as a retail store assistant would be entitled to a legal minimum wage of $12.97 per hour of he or she was employed on a full-time basis but $16.21 per hour on a casual contract.