Towards a post-liminal labour market

[H]owever utopian or unpalatable, costly or unrealistic, it might appear to us today, one thing is certain: as persistent and acute marginality of the kind that has plagued American and European cities over the past two decades continues to mount, strategies … will have to be reorganized in ways so drastic that they can hardly be foretold today.

(Wacquant 2008: 255−256)

Introduction

One of the key achievements of this book is to take a longer-term view of young people’s experiences in a changing labour market in ways that are theoretically informed and empirically evidenced using legacy and contemporary data. In much of the literature, there has been a tendency to exaggerate trends and to make claims about the contours of a future labour market that are little more than speculative. Here, we have been able to take the long view, focusing on major recessions and periods of relative prosperity in a way that has allowed us to avoid being caught up in specific moments when the worlds that young people inhabit seemed to be changing in radical, even unpredictable, ways. Writing at a time when much of the world is still suffering from a global financial crisis and the implementation of severe austerity measures that often take the greatest toll on young people, we have been able to show that trends that accelerated from 2007−8 began several decades earlier; thus linking past, present and potential futures.

Our analysis demonstrated that the labour conditions faced by young people have deteriorated over the long term, that jobs have become less secure and that new forms of employment disempower and disenfranchise the young generation. Opportunities for young people frequently involve temporary contracts, part-time working and work in occupations that provide little in the way of intrinsic fulfilment. Despite huge investments in education, underemployment is common, and social mobility has stalled. Life management has become more complex, with changes in employment having implications for the establishment of relationships and independent living. These changes are not confined to a period of ‘transition’ during youth and young adulthood but fundamentally alter the life course.

The words used and the concepts developed to describe and capture the essence of new and emerging social realities have sometimes encouraged us to depart from empirical realities. Here we have taken issue with Guy Standing (2011) and the term he coined, ‘the precariat’. While building on ideas with origins in French sociology that, rightly, alerted us to the ways in which ‘new’ conditions of labour simulated marginality and disempowered the working classes, Standing’s mistake lay not in the way he moved forwards the debate about the jeopardisation of labour (Castel 2003) but in the implication that marginality was becoming democratised through merging the ‘truly disadvantaged’ (Wilson 1990) with those in insecure or ‘atypical’ forms of employment.

The marginalisation and suffering of those without work, those unable to work and those barely able to obtain sufficient hours of employment to obtain a decent standard of living, to adequately feed their families and to escape the punitive intrusions and frequent threats that emanate from the agents of welfare policy, are far from new: novelists such as Zola and Dickens and social scientists such as Marx and Engels and Seebohm Rowntree described conditions similar to those we observe today from the early days of the industrial revolution through to Europe in the post-Second World War era.

The working poor have always been with us, as has labour precarity. From seasonal agricultural work that long predated the industrial revolution to the casualised labour that was the norm in UK ports until Attlee’s post-war Labour government introduced the National Dock Labour Scheme1 as a means of guaranteeing dockers the legal right to minimum work, holidays and sick pay, ‘precarious’ work has always been part of the employment landscape.

While we accept that insecure, fragmented and non-standard forms of employment have been growing and accelerated in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), we have argued that these trends have deep roots and that referring to this heterogeneous group of workers as ‘the precariat’ is misleading. The group of workers that stand between ‘traditional’ full-time employees and those who are workless, severely constrained or marginalised are an extremely varied group; certainly, some are little different from those who are marginalised and may experience regular churn between the two positions. Others, often those with human or cultural capital, pass through this zone fleetingly, or may represent a labour aristocracy of high-skill, high-wage workers in contract-based occupations such as broadcasting or pilots with budget airlines. Some young people who occupy this zone have made positive choices and may be taking control of a life that would otherwise be severely constrained through the practices of the agents of welfare policy. Not all young people want to live a life within the predictable parameters of a Fordist career where 1 day, 1 week, 1 month resembles the next. Indeed, some young people choose frugal lives and downgrade from ‘traditional’ jobs to McJobs in order to free ‘temporal and mental space to be creative’ and build lives that are fulfilling and hopeful outside of a normative employment nexus (Threadgold 2015).

Rather than use or adapt the term precarity that brings in its train uniformly negative connotations and suggests commonality of experience and even coherence as a collectivity, as argued in Chapter 3, we introduced the term liminality and the zone of liminality. In this way, we build on a solid anthropological tradition initiated by van Gennep (1960) in which he recognised the ways in which previous continuities and certainties are opened to challenge with fluid and malleable realities, or liquid modernity, to put it another way (Bauman 2000), representing new contexts in which lives are lived (with both positive and negative connotations).

Thus, the zone of liminality is a zone where outcomes are uncertain and in which people may develop a range of objective pathways which may be subjectively negotiated in a variety of ways. It is a zone which represents a changed reality, but also one that involves frequent changes in the ways in which individuals manage and interpret the foundations of their lives with the offer of a perspective free of the traditions of a Fordist life, which can be both liberating and threatening. For Turner (1969), the liminal stage can also lead to the emergence of new structures and changing hierarchies as people from different communities, or classes, are brought into new proximities. In the liminal zone, for example, young people from middle-class families with university degrees may find themselves working alongside early school leavers from poor families; even where these proximities are fleeting, they may bring about fresh understandings of populations that traditionally only mixed in hierarchical situations.

Reflecting on change

One of the most significant changes affecting young people’s experiences in the labour market, and their lives more generally, is the expansion of education. While it is true that recent increases in educational participation and attainment have not increased the prospects of social mobility, education can open horizons and impact on aspirations and expectations in work and non-work contexts. For those who go to university, if nothing else, the experience provides them with an expanded period between dependence and the burdens of domestic responsibility where they can contemplate future lives and dip their toes into the labour market. Yet, participation in higher education carries costs: most obviously, the implications of fee changes that mean many graduates emerge from university with significant debt that may restrict their ability to enter the housing market or may necessitate taking the first available job in order to service credit-card debts (Furlong and Cartmel 2009). There are also potential subjective costs involved, where young people invest in an expected graduate career and find themselves working in routine, often insecure, forms of employment. However, there is some evidence that expectations have been depressed, with some seeing a degree as a minimum qualification rather than a clear route to a graduate career.

Both graduates and non-graduates frequently experience insecure and atypical forms of employment: for some, these are temporary and represent stepping stones to more traditional careers, whereas others are churned between insecure jobs and worklessness or remain in this liminal state in the long term. As employment opportunities have changed, so have subjective orientations. There is evidence that some young people regard the new landscape of employment as normal, and there are minority groups who use the changes to their advantage. At the same time, there is a clear downside reflected not just in financial health and security, but in subjective adjustments necessary to manage complex lives.

The ways in which governments have responded to various crises of employment and to the needs of vulnerable individuals have always been less than adequate. Policy has been framed under the assumption that improved situations can only be brought about by tackling an assumed deficit in the human capital possessed by young people rather than by addressing significant problems of demand. In policy, young people are regarded with suspicion, seen as work-shy and as not knowing what is best for themselves in the long term. Where training is provided, it is often of poor quality, delivered at a level that will not deliver any significant boost to human capital and ‘offered’ without due regard for the aspirations of the individual. Moreover, policies are often unsuited to modern-day circumstances in that they are underpinned by the idea that the labour market can be represented as a dichotomy between the employed and unemployed – or not in education, employment or training (NEET)/non-NEET – with the aim being to move people from a state of worklessness to employment. In policy, it is rare to see acknowledgement of a zone of liminality populated by a heterogeneous population with diverse needs, and there has been little serious effort to reframe policy in ways that acknowledge changed realities and new needs.

A strength of this volume is that it has enabled us to draw on previously under-exploited data in order to provide an overview of young people’s experiences of employment and unemployment and security and insecurity over time while highlighting macro-level changes and continuities. Data from two 1980s studies alongside that derived from a large-scale, nationally representative, contemporary dataset have given us an unprecedented understanding of the changing state of young people in the labour market.

Using data from the two periods, we introduced three zones of (in)security, facilitating a broad comparison of changes between two time periods (Table 6.1). This model takes us beyond the dualisms that have so far blinded us to the significance of the liminal zone and where young people survive in a space between security and insecurity and fall between the cracks in policy. Despite our best efforts, the accuracy of our comparisons is limited by the ways in which researchers, operating within the normative assumptions of the day, tried to capture the state of the labour market. Differences in the ways that information was captured reveal a change in some of the criteria used to define labour market positions, partly due to a tightening up of definitions used in the respective survey instruments, which themselves reflect policy changes over time, but also reflect one of the inevitable consequences of using datasets which were not designed for comparability and which reflect assumptions that were prevalent in the different periods. So, for example, the definition of part-time work changes over the period, and the criteria used to define the marginalised, particularly the definition of ‘unemployment’ and ‘out of the labour force’, became more nuanced as dualistic approaches started to be challenged.

Table 6.1 Defining zones of (in)security: 1980s, 2010s

1980s |

2010s |

|

Zone of traditionality |

Full-time jobs with open-ended contracts. |

Full-time jobs with open-ended contracts. |

Zone of liminality |

Employed on temporary contracts, working between 10 and 30 hours a week. |

Employed on temporary contracts, working between 16 and 30 hours a week. |

Zone of marginality |

Unemployed (including those not formally registered as unemployed), the workless, on government schemes, working in ‘fill-in jobs’. |

Unemployed (including those not formally registered as unemployed), the workless (including sick and disabled and carers), on government schemes, working fewer than 16 hours a week. |

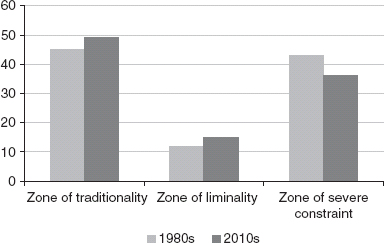

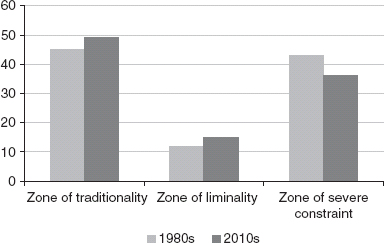

Comparing the zones across time reveals a slight increase in the size of the zone of traditionality (45 per cent to 49 per cent), counterbalanced by a corresponding decrease in the number of young people in the marginalised zone where we find the workless and those working very few hours (43 per cent compared to 36 per cent) (Figure 6.1). Compared to the 1980s, the liminal zone has increased in size (from 12 per cent to 15 per cent). Clearly, changes are relatively small, and, in these two periods characterised by high youth unemployment, the similarities appear greater than the differences. However, the composition of the liminal zone does vary over time in that in the 1980s it was skewed towards part-time workers, whereas in the contemporary period it is skewed temporary work and casual workers. In both periods, it is women and those residing in the weakest labour markets that suffer most.

Figure 6.1 Zones of (in)security: 1980s, 2010s

A particularly worrying change over time was the idea, introduced in Chapter 3, of a ‘punitive turn’ in policy triggered by a shift in policy and the underlying attitude from a culture of compassion to a culture of blame. The emergence of the new regime, palpable from the early 1980s, saw unemployed young people beginning to be sanctioned for their failure to secure employment, for example, with the threat of benefits being withdrawn and work placements and training schemes becoming compulsory. This approach became more pronounced over time, as successive UK governments felt the need to control young people ever more closely. By 2011, sanctions included not simply the threat of cuts to benefit payments as suggested in the 1980s but the introduction of a range of forced labour schemes (e.g. the Help to Work Scheme) and full, long-term, withdrawal of state support as a sanction for non-compliance.

The treatment of young people in policy is directly linked to the neo-liberal agenda and the shift from collectivist to individualist perspectives. Citizens who push back against this agenda are faced with harsh sanctions and by ham-fisted attempts to force them to work within a policy agenda which many young people recognise as being irrelevant to the worlds they inhabit: effectively, civilising offences committed by the state against young people.

Despite an increase in educational participation over time, there has been relatively little reduction in the size and composition of the most disadvantaged group. In both periods, those young people who entered either of the insecure zones on leaving education had difficulties improving their position over time. The experience of being trapped in the marginalised zone or the liminal zone is further compounded for those living in depressed and declining labour markets where opportunities to move into the zone of traditionality are often scarce. By contrast, in both time periods, the young people who entered the zone of traditionality on leaving education were more likely to experience some stability, emphasising the importance of linear transitions from education to work rather than the non-linear alternatives involving greater insecurity (Furlong et al. 2003).

Well-being

Alongside the increasingly hostile and punitive policy environment and a challenging labour market, recognition of the impact of labour market experiences on young people’s psychological well-being received attention in both periods. In the 1980s, studies found that many young people were experiencing psychological difficulties adjusting to a new type of labour market (e.g. Banks and Ullah 1988), and this remained an issue for the 2010 generation (e.g. West 2009).

Currently, there is considerable concern about the mental health of young people, with special funding schemes for research launched recently in a number of countries, including the United Kingdom. This is unsurprising, as there is a wealth of evidence suggesting alarming levels of mental health issues among young people (West 2009; Eckersley 2009). Figures from Scotland, for example (which are not out of line with other countries in the global North), show that just over four in ten females and around a third of males show clinically significant levels of depression and anxiety (West 2009). There is a wide range of explanations for poor levels of well-being among young people, some of which relate to the labour market trends we have highlighted in this book.

Of particular significance are the ontological insecurities that arise as young people negotiate uncertain terrains in contexts where blame for failure rests on individuals, even when they have followed the best available advice and invested heavily in their own futures (Furlong and Cartmel 2007). Eckersley (2009) argues that personal control represents a significant protective factor for mental health and well-being, and where individuals have to negotiate fragmented experiences in the labour market and manage different components of their lives, then there are likely to be subjective consequences. In addition, Eckersley places some of the blame on a materialist culture, arguing that ‘materialism (the pursuit of money and possessions) breeds not happiness, but dissatisfaction, depression, anxiety, anger, isolation and alienation’ (2009: 357).

At the same time, the recent data that we analysed tended to suggest that many young people had adjusted to contemporary conditions − satisfaction with life and optimism regarding the future were not suggestive of an epidemic of misery. Despite reasonably healthy levels of satisfaction and optimism, a significant minority are badly affected by trends, especially those who occupy marginalised positions. Indeed, feelings of depression among the marginalised are four times higher than among those in full-time permanent employment.

There is a risk that the growing disjuncture between predominant policy discourses and the new normality is damaging to mental health as they can promote a sense that individual lives are unusual or flawed, even where they are clearly aligned with others members of their generation. There is still an assumption in policy that there is a gold standard of full-time, relatively stable employment that is attainable by all who make the necessary efforts and investments and display appropriate attitudes. Where the new normality is presented as inferior, obstacles are placed in the ways of individuals who are attempting to make fulfilling lives in circumstances that are not of their own choosing.

While it is entirely appropriate to draw attention to the ways in which labour market experiences can have damaging consequences for mental health, it is also important to recognise that, in both periods, levels of optimism were relatively high, and there was a sense that, for those entering the labour market in the 2010s, the challenging labour market conditions were simply ‘normality’ and something their own parents (many of whom were 1980s school leavers themselves) had been among the first to face.

The future

If we accept the argument outlined in this book − that the current difficulties faced by young people in the labour market are not part of a fleeting turmoil being experienced in the wake of the GFC but are clear trends that can be traced back to the 1970s and 1980s, suggestive of a future trajectory that will see insecure and fragmented forms of employment continue to grow − then we need to consider the implications for the lives of both the young and the not-so-young in future decades. In the ‘gig economy’, people have to build their lives in new ways, both objectively, as they seek to establish an acceptably sound financial base to keep a roof over their heads and food in their mouths, and subjectively, as they create the sense of normality and personal control that underpins well-being.

A shift away from material culture is a possible response, and already there is evidence that some young people are choosing this path (Threadgold 2015). Of course, a mass move in this direction undermines a capitalist economy driven by the consumption of ‘unnecessary’ goods and services. Although yet to be fully implemented in a major economy, the idea of providing all citizens with a living allowance that they would supplement with employment (the unconditional basic income or citizens wage) in the gig economy or in more traditional spheres can be seen in this context as an aid to the survival of consumer capitalism.

While such a change in policy may appear unnecessarily radical and unaffordable, we have to remember that through taxation and welfare systems, in the United Kingdom the taxpayer already subsidises employers who operate low-wage regimes and helps keep families afloat when wages received are insufficient to provide a decent standard of living. We suggest that the time has come for a welfare revolution and for a rethink of the ways we regulate employment in the modern world. Properly constructed, this would not simply be about mitigating risk, but would be designed in such a way that new forms of creativity are unleashed and new freedoms established.

One of the messages that comes through from the research is that a move from policies underpinned by punitive measures has to be replaced by a more permissive approach so as to stimulate creative approaches to life management in an era characterised by increasingly diverse pathways. While doubts have long been expressed about the effectiveness of punitive approaches, such as workfare, they are framed within a set of Fordist assumptions under which life patterns displayed a greater uniformity: in the new normality, ‘one size fits all’ approaches are counterproductive.

Approaches to policy that are fit for purpose in the contemporary era are best framed in a ‘bottom-up’ fashion. In other words, they need to be flexible enough to help young people on their own terms; to assist their efforts to create the life that they wish to establish for themselves, be it one that is strongly work-centred or one that has a stronger focus on relationships or leisure.

While young people are quite resilient and show signs of having taken on board new realities, the pressures that can be harmful psychologically are often ones imposed by older people framing policy, providing education or within their own families. Carrying with them assumptive worlds framed in a disappearing era, in their dealings with young people they attempt to smooth entry into a world with which they are familiar, often with little understanding of the new formalities or the ways in which young people have accommodated these changes subjectively. Thus, improving well-being among young people can be brought about through policy change rather than through individualised interventions.

To an extent, the problems we see in policy are also manifest in some of the academic literature on young people in which fragmented and insecure work forms are seen as part of modern transitions rather than as a state of liminality that, for some, will last a lifetime. New research questions need to focus on the ways in which lives are built and sustained against a backdrop of ongoing liminality involving objective insecurity and subjective uncertainty.

In this book, we have been critical of Standing’s (2011) portrayal of the precariat as a class and the underlying assumptions about the democratisation of disadvantage. For Standing, the precariat respond to their situation through anxiety, alienation, anomie and anger (reactions he refers to as the four As). Clearly, there are elements of all four responses among young people in the zones of marginality and liminality (as well as among some in secure employment); however, these states are far from universal, and even among the most disadvantaged groups we find evidence of positive adjustment and optimism. While Standing argues that anxiety, alienation, anomie and anger will increase as Fordist structures wither, he tends to overlook the resilience of youth and the creativity they employ to make lives in circumstances that older generations certainly regard as prejudicial to the establishment of a ‘good’ life.

While we are reluctant to end on a pessimistic note, recent indications suggest that the landscape of political discourse around opportunities for young people has changed little since the punitive turn, and the neo-liberal agenda is still being played out. In the United Kingdom, as in many other countries, the current policy framework is not fit for purpose, and much legislation is based on outdated assumptions. New protections for workers are long overdue, and punitive approaches are ineffective and ‘drastic’ measures are called for (Wacquant 2008: 56).

While educational participation has increased throughout this period, education is not only about employability and selectivity, or individualised social mobility, as such interventions will only reinforce the liminal characteristics of employment and young adulthood for many while alleviating it for increasingly few. Such education interventions are pointless without labour market interventions. As it stands, education simply extends the zone of liminality for the majority, with young people being ‘neither one thing nor another’ – neither students, workers nor unemployed, but at the same time all of these things.

Current labour market trends are not encouraging and make us mindful of Beck’s vision of ‘Brazilianization’ in which large populations survive in poverty and live their lives under conditions of extreme unpredictability. A more positive way forwards has to begin to identity ways in which liminal lives can be sustainable and fulfilling lives.

Note

1The National Dock Labour Scheme was introduced in 1947 and, aside from guaranteeing minimum conditions, it also gave trade unions influence over recruitment and dismissal. It was abolished in 1989 by the Thatcher government, leading to widespread strike action.