page 354

CHAPTER

TEN

10

Being an Effective Project Manager

page 355

I couldn’t wait to be the manager of my own project and run the project the way I thought it should be done. Boy, did I have a lot to learn!

—First-time project manager

This chapter is based on the premise that one of the keys to being an effective project manager is building cooperative relationships among different groups of people to complete projects. Project success does not just depend on the performance of the project team. Success or failure often depends on the contributions of top management, functional managers, customers, suppliers, contractors, and others.

The chapter begins with a brief discussion of the differences between managing and leading a project. The importance of engaging project stakeholders is then introduced. Managers require a broad influence base to be effective in this area. Different sources of influence are discussed and are used to describe how project managers build social capital. This management style necessitates constant interacting with different groups of people whom project managers depend on. Special attention is devoted to managing the critical relationship with top management and the importance of leading by example. The importance of gaining cooperation in ways that build and sustain the page 356trust of others is emphasized. The chapter concludes by identifying personal attributes associated with being an effective project manager. Subsequent chapters will expand on these ideas in a discussion of managing the project team and working with people outside the organization. It should be noted that the material presented in this chapter is from the point of view of a project manager assigned to a traditional, plan-driven project, although many of the ideas would apply to those leading agile projects. Applications will be addressed in Chapter 15.

10.1 Managing versus Leading a Project

In a perfect world, the project manager would simply implement the project plan and the project would be completed. The project manager would work with others to formulate a schedule, organize a project team, keep track of progress, and announce what needs to be done next, and then everyone would charge along. Of course, no one lives in a perfect world, and rarely does everything go according to plan. Project participants get testy; they fail to get along with each other; other departments are unable to fulfill their commitments; technical glitches arise; work takes longer than expected. The project manager’s job is to get the project back on track. A manager expedites certain activities; figures out ways to solve technical problems; serves as peacemaker when tensions rise; and makes appropriate trade-offs among the time, cost, and scope of the project.

However, project managers often do more than put out fires and keep the project on track. They also innovate and adapt to ever-changing circumstances. They sometimes have to deviate from what was planned and introduce significant changes in the project scope and schedule to respond to unforeseen threats or opportunities. For example, customers’ needs may change, requiring significant design changes midway through the project. Competitors may release new products that dictate crashing project deadlines. Working relationships among project participants may break down, requiring a reformulation of the project team. Ultimately, what was planned or expected in the beginning may be very different from what was accomplished by the end of the project.

Project managers are responsible for integrating assigned resources to complete the project according to plan. At the same time they need to initiate changes in plans and schedules as persistent problems make plans unworkable. In other words, managers want to keep the project going while making necessary adjustments along the way. According to Kotter (1990) these two different activities represent the distinction between management and leadership. Management is about coping with complexity, while leadership is about coping with change.

Good management brings about order and stability by formulating plans and objectives, designing structures and procedures, monitoring results against plans, and taking corrective action when necessary. Leadership involves recognizing and articulating the need to significantly alter the direction and operation of the project, aligning people to the new direction, and motivating them to work together to overcome hurdles produced by the change and to realize new objectives.

Strong leadership, while usually desirable, is not always necessary to successfully complete a project. Well-defined projects that encounter no significant surprises require little leadership, as might be the case in constructing a conventional apartment building in which the project manager simply administrates the project plan. Conversely, the higher the degree of uncertainty encountered on a project—whether in terms of changes in project scope, technological stalemates, or breakdowns in coordination between people—the more leadership is required. For example, strong page 357leadership would be needed for a software development project in which the parameters are always changing to meet developments in the industry.

It takes a special person to perform both roles well. Some individuals are great visionaries who are good at exciting people about change. Too often, though, these people lack the discipline or patience to deal with the day-to-day drudgeries of managing. Likewise, there are individuals who are very well organized and methodical but lack the ability to inspire others.

Strong leaders can compensate for their managerial weaknesses by having trusted assistants who oversee and manage the details of the project. Conversely, a weak leader can complement his strengths by having assistants who are good at sensing the need to change and rallying project participants. Still, one of the things that make good project managers so valuable to an organization is that they have the ability to both manage and lead a project. In doing so they recognize the need to create a social network that allows them to find out what needs to be done and obtain the cooperation necessary to achieve it.

10.2 Engaging Project Stakeholders

First-time project managers are eager to implement their own ideas and manage their people to successfully complete their project. What they soon find out is that project success depends on the cooperation of a wide range of individuals, many of whom do not directly report to them. For example, during the course of a system integration project, a project manager was surprised by how much time she was spending negotiating and working with vendors, consultants, technical specialists, and other functional managers:

Instead of working with my people to complete the project, I found myself being constantly pulled and tugged by demands of different groups of people who were not directly involved in the project but had a vested interest in the outcome.

Too often when new project managers do find time to work directly on the project, they adopt a hands-on approach to managing the project. They choose this style not because they are power-hungry egomaniacs but because they are eager to achieve results. They become quickly frustrated by how slowly things operate, the number of people that have to be brought on board, and the difficulty of gaining cooperation. Unfortunately, as this frustration builds, the natural temptation is to exert more pressure and get more heavily involved in the project. These project managers quickly earn the reputation of “micro managing” and begin to lose sight of the real role they play on guiding a project.

Some new managers never break out of this vicious cycle. Others soon realize that authority does not equal influence and that being an effective project manager involves managing a much more complex set of stakeholders than they had anticipated. They encounter a web of relationships that requires a much broader spectrum of influence than they felt was necessary or even possible.

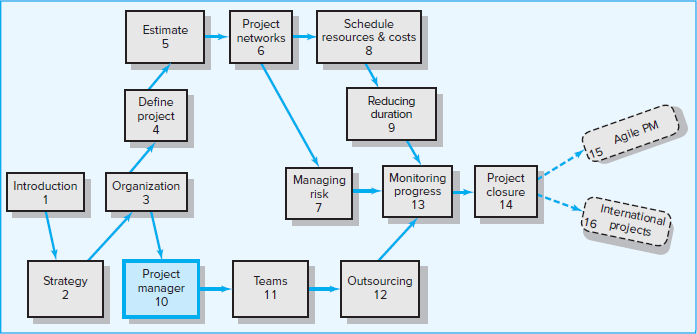

For example, a significant project, whether it involves renovating a bridge, creating a new product, or installing a new information system, will likely involve, in one way or another, working with a number of different groups of stakeholders. First, there is the core group of specialists assigned to complete the project. This group is likely to be supplemented at different times by professionals who work on specific segments of the project. Second, there are groups of people within the performing organization who are either directly or indirectly involved with the project. The most notable is top management, to whom the project manager is accountable. There are also other managers, page 358who provide resources and/or may be responsible for specific segments of the project, and administrative support services such as Human Resources, Finance, and so on. Depending on the nature of the project, a number of groups outside the organization influence the success of the project; the most important is the customer for which the project is designed (see Figure 10.1).

FIGURE 10.1

Network of Stakeholders

Each of these groups of stakeholders brings different expertise, standards, priorities, and agendas to the project. Stakeholders are people and organizations that are actively involved in the project or whose interests may be positively or negatively affected by the project (Project Management Institute, 2017). The sheer breadth and complexity of stakeholder relationships distinguish project management from regular management. To be effective, a project manager must understand how stakeholders can affect the project and develop methods for managing the dependency. The nature of these dependencies is identified here:

The project team manages and completes project work. Most participants want to do a good job, but they are also concerned with their other obligations and how their involvement on the project will contribute to their personal goals and aspirations.

Project managers naturally compete with each other for resources and the support of top management. At the same time they often have to share resources and exchange information.

Administrative support groups, such as human resources, information systems, purchasing agents, and maintenance, provide valuable support services. At the same time they impose constraints and requirements on the project such as the documentation of expenditures and the timely and accurate delivery of information.

page 359Functional managers, depending on how the project is organized, can play a minor or major role in project success. In matrix arrangements, they may be responsible for assigning project personnel, resolving technical dilemmas, and overseeing the completion of significant segments of the project work. Even in dedicated project teams, the technical input from functional managers may be useful, and acceptance of completed project work may be critical to in-house projects. Functional managers want to cooperate up to a point, but only up to a certain point. They are also concerned with preserving their status within the organization and minimizing the disruptions the project may have on their own operations.

Top management approves funding of the project and establishes priorities within the organization. They define success and adjudicate rewards for accomplishments. Significant adjustments in budget, scope, and schedule typically need their approval. They have a natural vested interest in the success of the project but, at the same time, have to be responsive to what is best for the entire organization.

Project sponsors champion the project and use their influence to gain approval of the project. Their reputation is tied to the success of the project, and they need to be kept informed of any major developments. They defend the project when it comes under attack and are a key project ally.

Contractors may do all the actual work—in some cases, with the project team merely coordinating their contributions. In other cases, they are responsible for ancillary segments of the project scope. Poor work and schedule slips can affect the work of the core project team. While contractors’ reputations rest with doing good work, they must balance their contributions with their own profit margins and their commitments to other clients.

Government agencies place constraints on project work. Permits need to be secured. Construction work has to be built to code. New drugs have to pass a rigorous battery of U.S. Food and Drug Administration tests. Other products have to meet safety standards, for example, Occupational Safety and Health Administration standards.

Vendors/suppliers provide the necessary resources for the completion of project work. Delays, shortages, and poor quality can bring a project to a standstill.

Other organizations, depending on the nature of the project, may directly or indirectly affect the project. For example, environmental groups may challenge or even block project work. Public interest groups may apply pressure on government agencies. Customers often hire consultants and auditors to protect their interests on a project.

Customers define the scope of the project, and ultimate project success rests in their satisfaction. Project managers need to be responsive to changing customer needs and requirements and to meeting their expectations. Customers are primarily concerned with getting a good deal and, as will be elaborated in Chapter 11, this naturally breeds tension with the project team.

These relationships are interdependent in that a project manager’s ability to work effectively with one group will affect his ability to engage other groups. For example, functional managers are likely to be less cooperative if they perceive that top management’s commitment to the project is waning. Conversely, the ability of the project manager to buffer the team from excessive interference from a client is likely to increase his standing with the project team.

The project management structure being used will influence the number and degree of external dependencies that need to be engaged. One advantage of creating page 360a dedicated project team is that it reduces dependencies, especially within the organization, because most of the resources are assigned to the project. Conversely, a functional matrix structure increases dependencies, with the result that the project manager is much more reliant upon functional colleagues for work and staff.

The old-fashioned view of managing projects emphasized planning and directing the project team; the new perspective emphasizes engaging project stakeholders and anticipating change as the most important jobs. Project managers need to be able to assuage the concerns of customers, sustain support for the project at higher levels of the organization, and quickly identify problems that threaten project work while defending the integrity of the project and the interests of the project participants.1

Within this web of relationships, the project manager must find out what needs to be done to achieve the goals of the project and build a cooperative network to accomplish it. Project managers must do so without the requisite authority to expect or demand cooperation. Doing so requires sound communication skills, political savvy, and a broad influence base. See Snapshot from Practice 10.1: The Project Manager as Conductor for more on what makes project managers special. See Research Highlight 10.1: Give and Take for an interesting finding regarding this concept.

page 361

10.3 Influence as Exchange

To successfully manage a project, a manager must adroitly build a cooperative network among divergent allies. Networks are mutually beneficial alliances that are generally governed by the law of reciprocity (Grant, 2013; Kaplan, 1984). The basic principle is that “one good deed deserves another, and likewise one bad deed deserves another.” The primary way to gain cooperation is to provide resources and services for others in exchange for future resources and services. This is the age-old maxim “Quid pro quo (something for something)” or, in today’s vernacular, “You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.”

Cohen and Bradford (1990) described the exchange view of influence as “currencies.” If you want to do business in a given country, you have to be prepared to use the appropriate currency, and the exchange rates can change over time as conditions change. In the same way, what is valued by a marketing manager may be different from what is valued by a veteran project engineer, and you are likely to need to use different influence currency to obtain the cooperation of each individual. Although this analogy is a bit of an oversimplification, the key premise holds true that in the long page 362run, “debit” and “credit” accounts must be balanced for cooperative relationships to work. Table 10.1 presents the commonly traded organizational currencies identified by Cohen and Bradford; they are then discussed in more detail in the following sections.

TABLE 10-1

Commonly Traded Organizational Currencies

| Task-related currencies | |

| Resources | Lending or giving money, budget increases, personnel, etc. |

| Assistance | Helping with existing projects or undertaking unwanted tasks. |

| Cooperation | Giving task support, providing quicker response time, or aiding implementation. |

| Information | Providing organizational as well as technical knowledge. |

| Position-related currencies | |

| Advancement | Giving a task or assignment that can result in promotion. |

| Recognition | Acknowledging effort, accomplishments, or abilities. |

| Visibility | Providing a chance to be known by higher-ups or significant others in the organization. |

| Network/contacts | Providing opportunities for linking with others. |

| Inspiration-related currencies | |

| Vision | Being involved in a task that has larger significance for the unit, organization, customer, or society. |

| Excellence | Having a chance to do important things really well. |

| Ethical correctness | Doing what is “right” by a higher standard than efficiency. |

| Relationship-related currencies | |

| Acceptance | Providing closeness and friendship. |

| Personal support | Giving personal and emotional backing. |

| Understanding | Listening to others’ concerns and issues. |

| Personal-related currencies | |

| Challenge/learning | Sharing tasks that increase skills and abilities. |

| Ownership/involvement | Letting others have ownership and influence. |

| Gratitude | Expressing appreciation. |

Source: Adapted from A. R. Cohen and David L. Bradford, Influence without Authority (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1990).

Task-Related Currencies

Task-related currencies come in different forms and are based on the project manager’s ability to contribute to others’ accomplishing their work. Probably the most significant form of this currency is the ability to respond to subordinates’ requests for additional manpower, money, or time to complete a segment of a project. This kind of currency is also evident in sharing resources with another project manager who is in need. At a more personal level, it may simply mean providing direct assistance to a colleague in solving a technical problem.

Providing a good word for a colleague’s proposal or recommendation is another form of this currency. Because most work of significance is likely to generate some form of opposition, the person who is trying to gain approval for a plan or proposal can be greatly aided by having a “friend in court.”

Another form of this currency includes extraordinary effort. For example, fulfilling an emergency request to complete a design document in two days instead of the normal four days is likely to engender gratitude. Finally, sharing valuable information that would be useful to other managers is another form of this currency.

page 363

Position-Related Currencies

Position-related currencies stem from the manager’s ability to enhance others’ positions within their organization. A project manager can do this by giving someone a challenging assignment that can aid her advancement by developing her skills and abilities. Being given a chance to prove yourself naturally generates a strong sense of gratitude. Sharing the glory and bringing to the attention of higher-ups the efforts and accomplishments of others generate goodwill.

Project managers confide that a useful strategy for gaining the cooperation of professionals in other departments/organizations is figuring out how to make these people look good to their bosses. For example, a project manager worked with a subcontractor whose organization was heavily committed to total quality management (TQM). The project manager made it a point in top-level briefing meetings to point out how quality improvement processes initiated by the contractor contributed to cost control and problem prevention.

Another variation of recognition is enhancing the reputation of others within the firm. “Good press” can pave the way for lots of opportunities, while “bad press” can quickly shut a person off and make it difficult to perform. This currency is also evident in helping to preserve someone’s reputation by coming to the defense of someone unjustly blamed for project setbacks.

Finally, one of the strongest forms of this currency is sharing contacts with other people. Helping individuals expand their own networks by introducing them to key people naturally engenders gratitude. For example, suggesting to a functional manager that he should contact Sally X if he wants to find out what is really going on in that department or to get a request expedited is likely to engender a sense of indebtedness.

Inspiration-Related Currencies

Inspiration-related currencies are perhaps the most powerful form of influence. Most sources of inspiration derive from people’s burning desire to make a difference and add meaning to their lives. Creating an exciting, bold vision for a project can elicit extraordinary commitment. For example, many of the technological breakthroughs associated with the introduction of the original Macintosh computer were attributed to the feeling that the project members had a chance to change the way people approached computers. A variant form of vision is providing an opportunity to do something really well. Being able to take pride in your work often drives many people.

Often the very nature of the project provides a source of inspiration. Discovering a cure for a devastating disease, introducing a new social program that will help those in need, or simply building a bridge that will reduce a major traffic bottleneck can provide opportunities for people to feel good about what they are doing and to feel that they are making a difference. Inspiration operates as a magnet—pulling people as opposed to pushing people toward doing something.

Relationship-Related Currencies

Relationship-related currencies have more to do with strengthening the relationship with someone than directly accomplishing the project tasks. The essence of this form of influence is forming a relationship that transcends normal professional boundaries and extends into the realm of friendship. Such relationships develop by giving personal and emotional backing. Picking people up when they are feeling down, boosting their confidence, and providing encouragement naturally breed goodwill. Sharing a sense of humor and making difficult times fun is another form of this currency. Similarly, engaging in non–work-related activities such as sports and family outings is another way relationships are naturally enhanced.

page 364

Perhaps the most basic form of this currency is simply listening to other people. Psychologists suggest that most people have a strong desire to be understood and that relationships break down because the parties stop listening to each other. Sharing personal secrets/ambitions and being a wise confidant also creates a special bond between individuals.

Personal-Related Currencies

Personal-related currencies deal with individual needs and an overriding sense of self-esteem. Some argue that self-esteem is a primary psychological need; the extent to which you can help others feel a sense of importance and personal worth will naturally generate goodwill. A project manager can enhance a colleague’s sense of worth by asking for help and seeking opinions, delegating authority over work, and allowing individuals to feel comfortable stretching their abilities. This form of currency can also be seen in sincere expressions of gratitude for the contributions of others. Care, though, must be exercised in expressing gratitude, since it is easily devalued when overused. That is, the first thank you is likely to be more valued than the fiftieth.

The bottom line is that a project manager will be influential only insofar as she can offer something that others value. Furthermore, given the diverse cast of people a project manager depends on, it is important that she be able to acquire and exercise different influence currencies. The ability to do so will be constrained in part by the nature of the project and how it is organized. For example, a project manager who is in charge of a dedicated team has considerably more to offer team members than a manager who is given the responsibility of coordinating the activities of different professionals across different departments and organizations. In such cases, that manager will probably have to rely more heavily on personal and relational bases of influence to gain the cooperation of others.

10.4 Social Network Building

Mapping Stakeholder Dependencies

The first step to social network building is identifying those stakeholders on whom the project depends for success. The project manager and his key assistants need to ask the following questions:

Whose cooperation will we need?

Whose agreement or approval will we need?

Whose opposition would keep us from accomplishing the project?

Many project managers find it helpful to draw a map of these dependencies. For example, Figure 10.2 contains the dependencies identified by a project manager responsible for installing a new financial software system in her company.

FIGURE 10.2

Stakeholder Map for Financial Software Installation Project

It is always better to overestimate rather than underestimate dependencies. All too often, otherwise talented and successful project managers have been derailed because they were blindsided by someone whose position or power they had not anticipated. After identifying the stakeholders associated with your project, it is important to assess their significance. Here the power/interest matrix introduced in Chapter 3 becomes useful. Those individuals with the most power over and interest in the project are the most significant stakeholders and deserve the greatest attention. In particular, you need to “step into their shoes” and see the project from their perspective by asking the following questions:

What differences exist between myself and the people on whom I depend (goals, values, pressures, working styles, risks)?

page 365How do these different people view the project (supporters, indifferents, antagonists)?

What is the current status of the relationship I have with the people I depend on?

What sources of influence do I have relative to those on whom I depend?

Once you start this analysis you can begin to appreciate what others value and what currencies you might have to offer as a basis on which to build a working relationship. You begin to realize where potential problems lie—relationships in which you have a current debit or no convertible currency. Furthermore, diagnosing others’ points of view as well as the basis for their positions will help you anticipate their reactions and feelings about your decisions and actions. This information is vital for selecting the appropriate influence strategy and tactics and producing win/win solutions.

For example, after mapping her dependency network, the project manager who was in charge of installing the software system realized that she was likely to have serious problems with the manager of the Receipts Department, who would be one of the primary users of the software. She had no previous history of working with this individual but had heard through the grapevine that the manager was upset with the choice of software and that he considered this project to be another unnecessary disruption of his department’s operation.

Prior to project initiation the project manager arranged to have lunch with the manager, where she sat patiently and listened to his concerns. She invested additional time and attention to educate him and his staff about the benefits of the new software. She tried to minimize the disruptions the transition would cause in his department. She altered the implementation schedule to accommodate his preferences as to when the software would be installed and the subsequent training would occur. In turn, the receipts manager and his people were much more accepting of the change, and the transition to the new software went more smoothly than anticipated.

page 366

Management by Wandering Around (MBWA)

The preceding example illustrates a key point—project management is a “contact sport.” Once you have established who the key players are, then you initiate contact and begin to build a relationship with those players. Building this relationship requires an interactive management style employees at Hewlett Packard referred to as management by wandering around (MBWA) to reflect that managers spend the majority of their time outside their offices. MBWA is somewhat of a misnomer in that there is a purpose/pattern behind the “wandering.” Through face-to-face interactions, project managers are able to stay in touch with what is really going on in the project and build cooperation essential to project success.

Effective project managers initiate contact with key players to keep abreast of developments, anticipate potential problems, provide encouragement, and reinforce the objectives and vision of the project. They are able to intervene to resolve conflicts and prevent stalemates from occurring. In essence, they “manage” the project. By staying in touch with various aspects of the project they become the focal point for information. Participants turn to them to obtain the most current and comprehensive information about the project, which reinforces their central role as project manager.

We have also observed less effective project managers who eschew MBWA and attempt to manage projects from their offices and computer terminals. Such managers proudly announce an open-door policy and encourage others to see them when a problem or an issue comes up. To them, no news is good news. This allows their contacts to be determined by the relative aggressiveness of others. Those who take the initiative and seek out the project manager get too high a proportion of the project manager’s attention. Those people less readily available (physically removed) or more passive get ignored. This behavior contributes to the adage “Only the squeaky wheel gets greased,” which breeds resentment within the project team.

Effective project managers also find the time to interact regularly with more distal stakeholders. They keep in touch with suppliers, vendors, top management, and other functional managers. In doing so they maintain familiarity with different parties, sustain friendships, discover opportunities to do favors, and understand the motives and needs of others. They remind people of commitments and champion the cause of their project. They also shape people’s expectations (see Snapshot from Practice 10.2: Managing Expectations). Through frequent communication they alleviate people’s concerns about the project, dispel rumors, warn people of potential problems, and lay the groundwork for dealing with setbacks in a more effective manner.

Unless project managers take the initiative to build a supportive network up front, they are likely to see a manager (or other stakeholder) only when there is bad news or when they need a favor (e.g., they don’t have the data they promised or the project has slipped behind schedule). Without prior, frequent, easy give-and-take interactions around nondecisive issues, the encounter prompted by the problem is likely to provoke excess tension. The parties are more likely to act defensively, interrupt each other, and lose sight of the common goal.

Experienced project managers recognize the need to build relationships before they need them. They initiate contact with the key stakeholders at times when there are no outstanding issues or problems and therefore no anxieties and suspicions. On these social occasions, they naturally engage in small talk and responsive banter. They respond to others’ requests for aid, provide supportive counsel, and exchange information. In doing so they establish good feelings which will allow them to deal with more serious problems down the road. When one person views another as pleasant, credible, page 367and helpful based on past contact, she is much more likely to be responsive to requests for help and less confrontational when problems arise.2

Managing Upward Relations

Research consistently points out that project success is strongly affected by the degree to which a project has the support of top management.3 Such support is reflected in an appropriate budget, responsiveness to unexpected needs, and a clear signal to others in the organization of the importance of the project and the need to cooperate.

Visible top management support is not only critical for securing the support of other managers within an organization but also key in the project manager’s ability to motivate the project team. Nothing establishes a manager’s right to lead more than his ability to defend. To win the loyalty of team members, project managers have to be effective advocates for their projects. They have to be able to get top management to rescind unreasonable demands, provide additional resources, and recognize the accomplishments of team members. This is more easily said than done.

page 368

Working relationships with upper management are a common source of consternation. Laments like the following are often made by project managers about upper management:

They don’t know how much it sets us back losing Neil to another project.

I would like to see them get this project done with the budget they gave us.

I just wish they would make up their minds as to what is really important.

While it may seem counterintuitive for a subordinate to “manage” a superior, smart project managers devote considerable time and attention to influencing and garnering the support of top management. Project managers have to accept profound differences in perspective and become skilled at the art of persuading superiors.

Many of the tensions that arise between upper management and project managers are a result of differences in perspective. Project managers become naturally absorbed with what is best for their project. To them the most important thing in the world is their project. Top management should have a different set of priorities. They are concerned with what is best for the entire organization. It is only natural for these two interests to conflict at times. For example, a project manager may lobby intensively for additional personnel, only to be turned down because top management believes that the other departments cannot afford a reduction in staff. Although frequent communication can minimize differences, the project manager has to accept the fact that top management is inevitably going to see the world differently.

Once project managers accept that disagreements with superiors are more a question of perspective than substance, they can focus more of their energy on the art of persuading upper management. But before they can persuade superiors, they must first prove loyalty (Sayles, 1989). Loyalty in this context simply means that most of the time project managers consistently follow through on requests and adhere to the parameters established by top management without a great deal of grumbling or fuss. Once managers have proven loyalty to upper management, senior management is much more receptive to their challenges and requests.

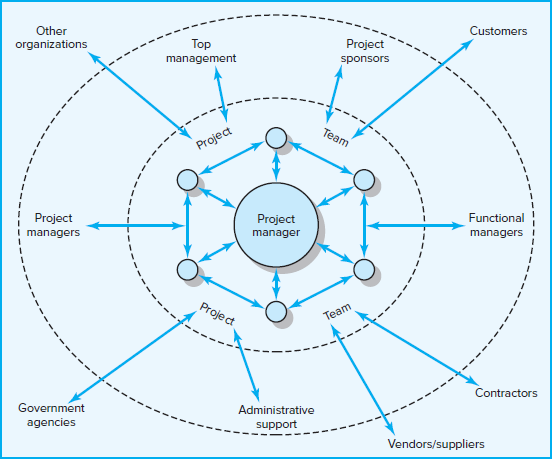

Project managers have to cultivate strong ties with upper managers who are sponsoring the project. As noted earlier, these are high-ranking officials who have championed approval and funding of the project; as such, their reputations are aligned with the project. Sponsors are also the ones who defend the project when it is under attack in upper circles of management. They shelter the project from excessive interference (see Figure 10.3). Project managers should always keep such people informed of any problems that may cause embarrassment or disappointment. For example, if costs are beginning to outrun the budget or a technical glitch is threatening to delay the completion of the project, managers make sure that the sponsors are the first to know.

FIGURE 10.3

Significance of a Project Sponsor

Timing is everything. Asking for additional budget the day after disappointing third-quarter earnings are reported is going to be much more difficult than making a similar request four weeks later. Good project managers pick the optimum time to appeal to top management. They enlist their project sponsors to lobby their cause. They also realize there are limits to top management’s accommodations. Here, the Lone Ranger analogy is appropriate—you have only so many silver bullets, so use them wisely.

Project managers need to adapt their communication pattern to that of the senior group. For example, one project manager recognized that top management had a tendency to use sports metaphors to describe business situations, so she framed a recent slip in schedule by admitting that “we lost five yards, but we still have two plays to make a first down.” Smart project managers learn the language of top management and use it to their advantage.

page 369

Finally, a few project managers admit ignoring chains of command. If they are confident that top management will reject an important request and that what they want to do will benefit the project, they do it without asking permission. While acknowledging that this is very risky, they claim that bosses typically won’t argue with success.

Leading by Example

A highly visible, interactive management style not only is essential to building and sustaining cooperative relationships but also allows project managers to utilize their most powerful leadership tool—their own behavior (Kouzes & Posner, 2012; Peters, 1988). Often, when faced with uncertainty, people look to others for cues as to how to respond and demonstrate a propensity to mimic the behavior of people they respect. A project manager’s behavior symbolizes how other people should work on the project. Through his behavior, a project manager can influence how others act and respond to a variety of issues related to the project. (See Snapshot from Practice 10.3: Leading at the Edge for a dramatic example of this.)

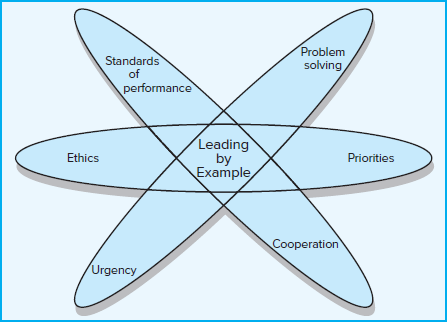

To be effective, project managers must “walk the talk” (see Figure 10.4). Six aspects of leading by example are discussed next.

FIGURE 10.4

Leading by Example

Priorities

Actions speak louder than words. Subordinates and others discern project managers’ priorities by how they spend their time. If a project manager claims that this project is critical and then is perceived as devoting more time to other projects, then all her verbal reassurances are likely to fall on deaf ears. Conversely a project manager who takes the time to observe a critical test instead of simply waiting for a report affirms the importance of the testers and their work. Likewise, the types of questions project managers pose communicate priorities. By repeatedly asking how specific issues relate to satisfying the customer, a project manager can reinforce the importance of customer satisfaction.

page 370

Urgency

Through their actions, project managers can convey a sense of urgency, which can permeate project activities. This urgency in part can be conveyed through stringent deadlines, frequent status report meetings, and aggressive solutions for expediting the page 371project. The project manager uses these tools like a metronome to pick up the beat of the project. At the same time, such devices will be ineffective if there is not also a corresponding change in the project manager’s behavior. If project managers want others to work faster and solve problems quicker, then they need to work faster. They need to hasten the pace of their own behavior. They should accelerate the frequency of their interactions, talk and walk more quickly, get to work sooner, and leave work later. By simply increasing the pace of their daily interaction patterns, project managers can reinforce a sense of urgency in others.

Problem Solving

How project managers respond to problems sets the tone for how others tackle problems. If bad news is greeted by verbal attacks, then others will be reluctant to be forthcoming.4 If the project manager is more concerned with finding out who is to blame instead of how to prevent problems from happening again, then others will tend to cover their tracks and cast the blame elsewhere. If, on the other hand, project managers focus more on how they can turn a problem into an opportunity or what can be learned from a mistake, then others are more likely to adopt a more proactive approach to problem solving.

Cooperation

How project managers act toward outsiders influences how team members interact with outsiders. If a project manager makes disparaging remarks about the “idiots” in the Marketing Department, then this oftentimes becomes the shared view of the entire team. If project managers set the norm of treating outsiders with respect and being responsive to their needs, then others will more likely follow suit.

Standards of Performance

Veteran project managers recognize that if they want participants to exceed project expectations, then they have to exceed others’ expectations of a good project manager. They establish a high standard for project performance through the quality of their daily interactions. They respond quickly to the needs of others, carefully prepare and run crisp meetings, stay on top of all the critical issues, facilitate effective problem solving, and stand firm on important matters.

Ethics

How others respond to ethical dilemmas that arise in the course of a project will be influenced by how the project manager has responded to similar dilemmas. In many cases, team members base their actions on how they think the project manager would respond. If project managers deliberately distort or withhold vital information from customers or top management, then they are signaling to others that this kind of behavior is acceptable. Project management invariably creates a variety of ethical dilemmas; this would be an appropriate time to delve into this topic in more detail.

page 372

10.5 Ethics and Project Management

Questions of ethics have already arisen in previous chapters that discussed padding of cost and time estimations, exaggerating pay-offs of project proposals, and so forth. Ethical dilemmas involve situations where it is difficult to determine whether conduct is right or wrong.

In a survey of project managers, 81 percent reported that they encounter ethical issues in their work.5 These dilemmas include being pressured to alter status reports, backdate signatures, compromising safety standards to accelerate progress, and approving shoddy work. The more recent work of Müller and colleagues suggests that the most common dilemma project managers face involves transparency issues related to project performance (Müller et al., 2013, 2014). For example, is it acceptable to falsely assure customers that everything is on track when in reality you are doing so to prevent them from panicking and making matters even worse?

Project management is complicated work, and, as such, ethics invariably involve gray areas of judgment and interpretation. For example, it is difficult to distinguish deliberate falsification of estimates from genuine mistakes or the willful exaggeration of project payoffs from genuine optimism. It becomes problematic to determine whether unfulfilled promises were deliberate deception or an appropriate response to changing circumstances.

To provide greater clarity to business ethics, many companies and professional groups publish a code of conduct. Cynics see these documents as simply window dressing, while advocates argue that they are important, albeit limited, first steps. In practice, personal ethics do not lie in formal statutes but at the intersection of one’s work, family, education, profession, religious beliefs, and daily interactions. Most project managers report that they rely on their own private sense of right and wrong—what one project manager called his “internal compass.” One common rule of thumb for testing whether a response is ethical is to ask, “Imagine that whatever you did was going to be reported on the front page of your local newspaper. How would you like that? Would you be comfortable?”

Unfortunately, scandals at Wells Fargo, Enron, Worldcom, and Arthur Andersen have demonstrated the willingness of highly trained professionals to abdicate personal responsibility for illegal actions and to obey the directives of superiors (see Snapshot from Practice 10.4: The Collapse of Arthur Andersen). Top management and the culture of an organization play a decisive role in shaping members’ beliefs of what is right and wrong. Many organizations encourage ethical transgressions by creating a “win at all cost” mentality. The pressures to succeed obscure the consideration of whether the ends justify the means. Other organizations place a premium on “fair play” and command a market position by virtue of being trustworthy and reliable.6

Many project managers claim that ethical behavior is its own reward. By following your own internal compass, your behavior expresses your personal values. Others suggest that ethical behavior is doubly rewarding. You not only are able to fall asleep at night but also develop a sound and admirable reputation. As will be explored in the next section, such a reputation is essential to establishing the trust necessary to exercise influence effectively.

page 373

10.6 Building Trust: The Key to Exercising Influence

The significance of trust can be discerned by its absence. Imagine how different a working relationship is when you distrust the other party as opposed to trusting them. Here is what one line manager had to say about how he reacted to a project manager he did not trust:

Whenever Jim approached me about something, I found myself trying to read between the lines to figure what was really going on. When he made a request, my initial reaction was “no” until he proved it.

page 374

Conversely trust is the “lubricant” that maintains smooth and efficient interactions. For example, here is what a functional manager had to say about how he dealt with a project manager he trusted:

If Sally said she needed something, no questions were asked. I knew it was important or she wouldn’t have asked. Likewise, if I needed something, I knew she would come through for me if she could.

Trust is an elusive concept. It is hard to nail down in precise terms why some project managers are trusted and others are not. One popular way to understand trust is to see it as a function of character and competence. Character focuses on personal motives (e.g., does he or she want to do the right thing?), while competence focuses on skills necessary to realize motives (e.g., does he or she know the right things to do?).

Stephen Covey resurrected the significance of character in the leadership literature in his best-selling Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. Covey criticized popular management literature as focusing too much on shallow human relations skills and manipulative techniques, which he labeled the personality ethic. He argues that at the core of highly effective people is a character ethic that is deeply rooted in personal values and principles such as dignity, service, fairness, the pursuit of truth, and respect.

One of the distinguishing traits of character is consistency. When people are guided by a core set of principles, they are naturally more predictable because their actions are consistent with these principles. Another feature of character is openness. When people have a clear sense of who they are and what they value, they are more receptive to others. This trait provides them with the capacity to empathize and the talent to build consensus among divergent people. Finally, another quality of character is a sense of purpose. Managers with character are driven not only by personal ambitions but also for the common good. Their primary concern is what is best for their organization and the project, not what is best for themselves. This willingness to subordinate personal interests to a higher purpose garners the respect, loyalty, and trust of others.

The significance of character is summarized by the comments made by two team members about two very different project managers:

At first everyone liked Joe and was excited about the project. But after a while, people became suspicious of his motives. He had a tendency to say different things to different people. People began to feel manipulated. He spent too much time with top management. People began to believe that he was only looking out for himself. It was HIS project. When the project began to slip he jumped ship and left us holding the bag. I’ll never work for that guy again.

My first impression of Jack was nothing special. He had a quiet, unassuming management style. Over time I learned to respect his judgment and his ability to get people to work together. When you went to him with a problem or a request, he always listened carefully. If he couldn’t do what you wanted him to do, he would take the time to explain why. When disagreements arose he always thought of what was best for the project. He treated everyone by the same rules; no one got special treatment. I’d jump at the opportunity to work on a project with him again.

Character alone will not engender trust. We must also have confidence in the competency of individuals before we really trust them (Kanter, 1979). We all know well-intended managers whom we like but do not trust because they have a history of coming up short on their promises. Although we may befriend these managers, we don’t like to work with or for them.

Competence is reflected at a number of different levels. First, there is task-related knowledge and skills reflected in the ability to answer questions, solve technical problems, and excel in certain kinds of work. Second, there is competence at an interpersonal level demonstrated in being able to listen effectively, communicate clearly, resolve arguments, provide encouragement, and so forth. Finally, there is organizational page 375competence. This includes being able to run effective meetings, set meaningful objectives, reduce inefficiencies, and build a social network. Too often young engineers and other professionals tend to place too much value on task or technical competence. They underestimate the significance of organizational skills. Veteran professionals, on the other hand, recognize the importance of management and place a greater value on organizational and interpersonal skills.

One problem new project managers experience is that it takes time to establish a sense of character and competency. Character and competency are often demonstrated when they are tested, such as when a tough call has to be made or when difficult problems have to be solved. Veteran project managers have the advantage of reputation and an established track record of success. Although endorsements from credible sponsors can help a young project manager create a favorable first impression, ultimately her behavior will determine whether she can be trusted. Recent research suggests that the first step in building trust is connecting. Instead of starting off emphasizing your competency, focus on exhibiting warmth and concern.7 In doing so, you demonstrate to others that you hear them, understand them, and can be trusted by them (Cuddy, Kohu, & Neffinger, 2013).

So far this chapter has addressed the importance of building a network of relationships to complete a project based on trust and reciprocity. The next section examines the nature of project management work and the personal qualities needed to excel at it.

10.7 Qualities of an Effective Project Manager

Project management is, at first glance, a misleading discipline in that there is an inherent logic to the process. There is a natural progression from formulating a project scope statement to creating a WBS, developing a network, adding resources, finalizing a plan, and reaching milestones. However, when it comes to actually implementing and completing projects, this logic can quickly disappear. Project managers often encounter a much messier world, filled with inconsistencies and paradoxes. Effective project managers have to be able to deal with the contradictory nature of their work. Some of those contradictions are listed here:

Innovate and maintain stability. Project managers have to put out fires, restore order, and get the project back on track. At the same time they need to be innovative and develop new, better ways of doing things. Innovations upset routines and may spark new disturbances that have to be dealt with.

See the big picture while getting their hands dirty. Project managers have to see the big picture and how their project fits within the larger strategy of their firm. There are also times when they must get deeply involved in project work and technology. If they don’t worry about the details, who will?

Encourage individuals but stress the team. Project managers have to motivate, cajole, and entice individual performers while maintaining teamwork. They have to be careful that they are considered fair and consistent in their treatment of team members while treating each member as a special individual.

Be hands-off/hands-on. Project managers have to intervene, resolve stalemates, solve technical problems, and insist on different approaches. At the same time they have to recognize when it is appropriate to sit on the sidelines and let other people figure out what to do.

page 376Be flexible but firm. Project managers have to be adaptable and responsive to events and outcomes that occur on the project. At the same time they have to hold the line at times and tough it out when everyone else wants to give up.

Manage team versus organizational loyalties. Project managers need to forge a unified project team whose members stimulate one another to extraordinary performance. But at the same time they have to counter the excesses of cohesion and the team’s resistance to outside ideas. They have to cultivate loyalties to both the team and the parent organization.

Managing these and other contradictions requires finesse and balance. Finesse involves the skillful movement back and forth between opposing behavioral patterns (Sayles, 1989). For example, most of the time project managers actively involve others, move by increment, and seek consensus. There are other times when project managers must act as autocrats and take decisive, unilateral action. Balance involves recognizing the danger of extremes and that too much of a good thing invariably becomes harmful. For example, many managers have a tendency to always delegate the most stressful, difficult assignments to their best team members. This habit often breeds resentment among those chosen (“why am I always the one who gets the tough work?”) and never allows the weaker members to develop their talents further.

There is no one management style or formula for being an effective project manager. The world of project management is too complicated for formulas. Successful project managers have a knack for adapting styles to specific circumstances of the situation.

So what should one look for in an effective project manager? Many authors have addressed this question and have generated list after list of skills and attributes associated with being an effective manager (Posner, 1987; Shenhar & Nofziner, 1997; Turner & Müller, 2005). When reviewing these lists, one sometimes gets the impression that to be a successful project manager requires someone with superhuman powers. While not everyone has the right stuff to be an effective project manager, there are some core traits and skills that can be developed to successfully perform the job. The following are eight of these traits.

Effective communication skills. Communication is critical to project success. Project managers need to speak the language of different stakeholders and be empathetic listeners.

Systems thinking. Project managers must be able to take a holistic rather than a reductionist approach to projects. Instead of breaking up a project into individual pieces (planning, budget) and managing it by understanding each part, a systems perspective focuses on trying to understand how relevant project factors collectively interact to produce project outcomes. The key to success then becomes managing the interaction between different parts and not the parts themselves.8

Personal integrity. Before you can lead and manage others, you have to be able to lead and manage yourself (Bennis, 1989). Begin by establishing a firm sense of who you are, what you stand for, and how you should behave. This inner strength provides the buoyancy to endure the ups and downs of the project life cycle and the credibility essential to sustaining the trust of others.

Proactivity. Good project managers take action before it is needed to prevent small concerns from escalating into major problems. They spend the majority of their page 377time working within their sphere of influence to solve problems and not dwelling on things they have little control over. Project managers can’t be whiners.9

High emotional intelligence (EQ). Project management is not for the meek. Project managers have to have command of their emotions and be able to respond constructively to others when things get a bit out of control. See Research Highlight 10.2: Emotional Intelligence to read more about this quality.

General business perspective. Because the primary role of a project manager is to integrate the contributions of different business and technical disciplines, it is important that a manager have a general grasp of business fundamentals and how the different functional disciplines interact to contribute to a successful business.

Effective time management. Time is a manager’s scarcest resource. Project managers have to be able to budget their time wisely and quickly adjust their priorities. They need to balance their interactions so no one feels ignored.

Optimism. Project managers have to display a can-do attitude. They have to be able to find rays of sunlight in a dismal day and keep people’s attention positive. A page 378good sense of humor and a playful attitude are often a project manager’s greatest strengths.

So how does one develop these traits? Workshops, self-study, and courses can upgrade one’s general business perspective and capacity for systems thinking. Training programs can improve emotional intelligence and communication skills. People can also be taught stress and time management techniques. However, we know of no workshop or magic potion that can transform a pessimist into an optimist or provide a sense of purpose when there is not one. These qualities get at the very soul or being of a person. Optimism, integrity, and even proactivity are not easily developed if there is not already a predisposition to display them.

Summary

To be successful, project managers must build a cooperative network among a diverse set of allies. They begin by identifying the key stakeholders on a project, then diagnose the nature of the relationships and the basis for exercising influence. Effective project managers are skilled at acquiring and exercising a wide range of influence. They use this influence and a highly interactive management style to monitor project performance and initiate appropriate changes in project plans and direction. They do so in a manner that generates trust, which is ultimately based on others’ perceptions of their character and competence.

Project managers are encouraged to keep in mind the following suggestions.

Relationships should be built before they are needed. Identify key players and what you can do to help them before you need their assistance. It is always easier to receive a favor after you have granted one. This requires the project manager to see the project in systems terms and to appreciate how it affects other activities and agendas inside and outside the organization. From this perspective they can identify opportunities to do good deeds and garner the support of others.

Trust is sustained through frequent face-to-face contact. Trust withers through neglect. This is particularly true under conditions of rapid change and uncertainty that naturally engender doubt, suspicion, and even momentary bouts of paranoia. Project managers must maintain frequent contact with key stakeholders to keep abreast of developments, assuage concerns, engage in reality testing, and focus attention on the project. Frequent face-to-face interactions either directly or by teleconferencing affirm mutual respect and trust in each other.

Ultimately, exercising influence in an effective and ethical manner begins and ends with how you view the other parties. Do you view them as potential partners or obstacles to your goals? If obstacles, then you wield your influence to manipulate and gain compliance and cooperation. If partners, you exercise influence to gain their commitment and support. People who view social network building as building partnerships see every interaction with two goals: resolving the immediate problem/concern and improving the working relationship so that next time it will be even more effective. Experienced project managers realize that “what goes around comes around” and try at all cost to avoid antagonizing players for quick success.

page 379

Key Terms

Review Questions

What is the difference between managing and leading a project?

What does the exchange model of influence suggest you do to build cooperative relationships to complete a project?

What differences would you expect to see between the kinds of influence currencies that a project manager in a functional matrix would use and the influence a project manager of a dedicated project team would use?

Why is it important to build a relationship before you need it?

Why is it critical to keep the project sponsor informed?

Why is trust a function of both character and competence?

Which of the eight traits/skills associated with being an effective project manager is the most important? The least important? Why?

SNAPSHOT  FROM PRACTICE

FROM PRACTICE

Discussion Questions

10.1 The Project Manager as Conductor

Why is a conductor of an orchestra an appropriate metaphor for a project manager?

What aspects of being a project manager are not reflected in this metaphor?

Can you think of other metaphors that would be appropriate?

10.3 Leading at the Edge

How important is leading by example on a project?

What do you think would have happened to the crew of the Endurance if Shackleton had not led by example?

10.4 The Collapse of Arthur Andersen

It seems like every 5–10 years a scandal damages, if not brings down, a well-known business. Is this inevitable, given the competitive nature of business?

What aspects of the Arthur Andersen culture contributed to the scandal?

Exercises

Do an Internet search for the Keirsey Temperament Sorter Questionnaire and find a site that appears to have a reputable self-assessment questionnaire. Respond to the questionnaire to identify your temperament type. Read supportive documents associated with your type. What does this material suggest are the kinds of projects that would best suit you? What does it suggest your strengths and weaknesses are as a project manager? How can you compensate for your weaknesses?

Access the Project Management Institute website and review the standards contained in the PMI Member Ethical Standards section. How useful is the information for helping someone decide what behavior is appropriate and inappropriate?

You are organizing a benefit concert in your hometown that will feature local heavy metal rock groups and guest speakers. Draw a dependency map identifying page 380the major groups of people that are likely to affect the success of this project. Who do you think will be most cooperative? Who do you think will be least cooperative? Why?

You are the project manager responsible for the overall construction of a new international airport. Draw a dependency map identifying the major groups of people that are likely to affect the success of this project. Who do you think will be most cooperative? Who do you think will be least cooperative? Why?

Identify an important relationship (co-worker, boss, friend) in which you are having trouble gaining cooperation. Assess this relationship in terms of the influence currency model. What kinds of influence currency have you been exchanging in this relationship? Is the “bank account” for this relationship in the “red” or the “black”? What kinds of influence would be appropriate for building a stronger relationship with that person?

The following seven mini-case scenarios involve ethical dilemmas associated with project management. How would you respond to each situation and why?

Jack Nietzche

You returned from a project staffing meeting in which future project assignments were finalized. Despite your best efforts, you were unable to persuade the director of project management to promote one of your best assistants, Jack Nietzche, to a project manager position. You feel a bit guilty because you dangled the prospect of this promotion to motivate Jack. Jack responded by putting in extra hours to ensure that his segments of the project were completed on time. You wonder how Jack will react to this disappointment. More importantly, you wonder how his reaction might affect your project. You have five days remaining to meet a critical deadline for a very important customer. While it won’t be easy, you believed you would be able to complete the project on time. Now you’re not so sure. Jack is halfway through completing the documentation phase, which is the last critical activity. Jack can be pretty emotional at times, and you are worried that he will blow up once he finds he didn’t get the promotion. As you return to your office, you wonder what you should do. Should you tell Jack that he isn’t going to be promoted? What should you say if he asks about whether the new assignments were made?

Seaburst Construction Project

You are the project manager for the Seaburst construction project. So far the project is progressing ahead of schedule and below budget. You attribute this in part to the good working relationship you have with the carpenters, plumbers, electricians, and machine operators who work for your organization. More than once you have asked them to give 110 percent, and they have responded.

One Sunday afternoon you decide to drive by the site and show it to your son. As you point out various parts of the project to your son, you discover that several pieces of valuable equipment are missing from the storage shed. When you start work again on Monday, you are about to discuss this matter with a supervisor when you realize that all the missing equipment is back in the shed. What should you do? Why?

The Project Status Report Meeting

You are driving to a project status report meeting with your client. You encountered a significant technical problem on the project that has put your project behind schedule. This is not good news because completion time is the number one priority for the project. You are confident that your team can solve the problem if they are free to give their undivided attention to it and that with hard work you can get back on schedule. You also believe if you tell the client about the problem, she will demand a meeting with your team to discuss the implications of the problem. You can also expect her to page 381send some of her personnel to oversee the solution to the problem. These interruptions will likely further delay the project. What should you tell your client about the current status of the project?

Gold Star LAN Project

You work for a large consulting firm and were assigned to the Gold Star LAN project. Work on the project is nearly completed and your clients at Gold Star appear to be pleased with your performance. During the course of the project, changes in the original scope had to be made to accommodate specific needs of managers at Gold Star. The costs of these changes were documented as well as overhead and submitted to the centralized Accounting Department. They processed the information and submitted a change order bill for your signature. You are surprised to see the bill is 10 percent higher than what you submitted. You contact Jim Messina in the accounting office and ask if a mistake has been made. He curtly replies that no mistake was made and that management adjusted the bill. He recommends that you sign the document. You talk to another project manager about this and she tells you off the record that overcharging clients on change orders is common practice in your firm. Would you sign the document? Why? Why not?

Cape Town Bio-Tech

You are responsible for installing the new Double E production line. Your team has collected estimates and used the WBS to generate a project schedule. You have confidence in the schedule and the work your team has done. You report to top management that you believe the project will take 110 days and be completed by March 5. The news is greeted positively. In fact, the project sponsor confides that orders do not have to be shipped until April 1. You leave the meeting wondering whether you should share this information with the project team or not?

Ryman Pharmaceuticals

You are a test engineer on the Bridge project at Ryman Pharmaceuticals. You have just completed conductivity tests of a new electrochemical compound. The results exceeded expectations. This new compound should revolutionize the industry. You are wondering whether to call your stockbroker and ask him to buy $20,000 worth of Ryman stock before everyone else finds out about the results. What would you do and why?

Princeton Landing

You are managing the renovation of the Old Princeton Landing Bar and Grill. The project is on schedule despite receiving a late shipment of paint. The paint was supposed to arrive on 1/30 but instead arrived on 2/1. The assistant store manager apologizes profusely for the delay and asks if you would be willing to sign the acceptance form and backdate it to 1/30. He says he won’t qualify for a bonus that he has worked hard to meet for the past month if the shipment is reported late. He promises to make it up to you on future projects. What would you do and why?

References

Anand, V., B. E. Ashforth, and M. Joshi, “Business as Usual: The Acceptance and Perpetuation of Corruption in Organizations,” Academy of Management Executive, vol. 19, no. 4 (2005), pp. 9–23.

Ancona, D. G., and D. Caldwell, “Improving the Performance of New-Product Teams,” Research Technology Management, vol. 33, no. 2 (March/April 1990), pp. 25–29.

Badaracco, J. L., Jr., and A. P. Webb, “Business Ethics: A View from the Trenches,” California Management Review, vol. 37, no. 2 (Winter 1995), pp. 8–28.

page 382

Baker, W. E., Network Smart: How to Build Relationships for Personal and Organizational Success (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994).

Bennis, W., On Becoming a Leader (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1989).

Bertsche, R., “Seven Steps to Stronger Relationships between Project Managers and Sponsors,” PM Network, September 2014, pp. 50–55.

Bourne, L., Stakeholder Relationship Management (Farnham, England: Gower Publishing Ltd., 2009).

Cabanis-Brewin, J., “The Human Task of a Project Leader: Daniel Goleman on the Value of High EQ,” PM Network, November 1999, pp. 38–42.

Cohen, A. R., and D. L. Bradford, Influence without Authority (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1990).

Cuddy, J. A., M. Kohu, and J. Neffinger, “Connect Then Lead,” Harvard Business Review, vol. 91, no. 7/8 (July/August 2013), pp. 54–61.

Dinsmore, P. C., “Will the Real Stakeholders Please Stand Up?” PM Network, December 1995, pp. 9–10.

Einsiedel, A. A., “Profile of Effective Project Managers,” Project Management Journal, vol. 31, no. 3 (1987), pp. 51–56.

Ferrazzi, K., Never Eat Alone and Other Secrets to Success One Relationship at a Time (New York: Crown Publishers, 2005).

Gabarro, S. J., The Dynamics of Taking Charge (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1987).

Hill, L. A., Becoming a Manager: Mastery of a New Identity (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1992).

Kanter, R. M., “Power Failures in Management Circuits,” Harvard Business Review (July/August 1979), pp. 65–79.

Kaplan, R. E., “Trade Routes: The Manager’s Network of Relationships,” Organizational Dynamics, vol. 12, no. 4 (Spring 1984), pp. 37–52.

Kotter, J. P., “What Leaders Really Do,” Harvard Business Review, vol. 68, no. 3 (May/June 1990), pp. 103–11.

Kouzes, J. M., and B. Z. Posner, Credibility: How Leaders Gain and Lose It, Why People Demand It (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993).

Kouzes, J. M., and B. Z. Posner, The Leadership Challenge, 5th ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2012).

Lewis, M. W., M. A. Welsh, G. E. Dehler, and S. G. Green, “Product Development Tensions: Exploring Contrasting Styles of Project Management,” Academy of Management Journal, vol. 45, no. 3 (2002), pp. 546–64.

page 383

Müller, R., and R. Turner, “Leadership Competency Profiles of Successful Project Managers,” International Journal of Project Management, vol. 28, no. 5 (July 2010), pp. 437–48.

Müller R., Erling S. Andersen, Ø. Kvalnes, J. Shao, S. Sankaran, J. R. Turner, C. Biesenthal, D. Walker, and S. Gudergan, “The Interrelationship of Governance, Trust, and Ethics in Temporary Organizations,” Journal of Project Management, vol. 44, no. 4 (August 2013), pp. 26–44.

Müller, R., R. Turner, E. Andersen, J. Shao, and O. Kvalnes, “Ethics, Trust, and Goverance in Temporary Organizations,” Journal of Project Management, vol. 45, no. 4 (August/September 2014), pp. 39–54.

Peters, L. H., “A Good Man in a Storm: An Interview with Tom West,” Academy of Management Executive, vol. 16, no. 4 (2002), pp. 53–63.

Peters, L. H., “Soulful Ramblings: An Interview with Tracy Kidder,” Academy of Management Executive, vol. 16, no. 4 (2002), pp. 45–52.

Peters, T., Thriving on Chaos: Handbook for a Management Revolution (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988).

Pinto, J. K., and D. P. Slevin, “Critical Success Factors in Successful Project Implementation,” IEEE Transactions in Engineering Management, vol. 34, no. 1 (1987), pp. 22–27.

Posner, B. Z., “What It Takes to Be an Effective Project Manager,” Project Management Journal (March 1987), pp. 51–55.

Project Management Institute, PMBOK Guide, 6th ed. (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2017).

Robb, D. J., “Ethics in Project Management: Issues, Practice, and Motive,” PM Network, December 1996, pp. 13–18.

Shenhar, A. J., and B. Nofziner, “A New Model for Training Project Managers,” Proceedings of the 28th Annual Project Management Institute Symposium, 1997, pp. 301–6.

Turner, J. R., and R. Müller, “The Project Manager Leadership Style as a Success Factor on Projects: A Literature Review,” Project Management Journal, vol. 36, no. 2 (2005), pp. 49–61.

page 384

Case 10.1

The Blue Sky Project*

Garth Hudson was a 29-year-old graduate of Eastern State University (ESU) with a BS degree in management information systems. After graduation he worked for seven years at Bluegrass Systems in Louisville, Kentucky. While at ESU he worked part time for an oceanography professor, Ahmet Green, creating a customized database for a research project he was conducting. Green was recently appointed director of Eastern Oceanography Institute (EOI), and Garth was confident that this prior experience was instrumental in his getting the job as information services (IS) director at the institute. Although he took a significant pay cut, he jumped at the opportunity to return to his alma mater. His job at Bluegrass Systems had been very demanding. The long hours and extensive traveling had created tension in his marriage. He was looking forward to a normal job with reasonable hours. Besides, Jenna, his wife, would be busy pursuing her MBA at Eastern State University. While at Bluegrass, Garth worked on a wide range of IS projects. He was confident that he had the requisite technical expertise to excel at his new job.

Eastern Oceanography Institute was an independently funded research facility aligned with Eastern State University. Approximately 50 full- and part-time staff worked at the institute. They worked on research grants funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the United Nations (UN), as well as research financed by private industry. There were typically 7 to 9 major research projects under way at any one time, as well as 20 to 25 smaller projects. One-third of the institute’s scientists had part-time teaching assignments at ESU and used the institute to conduct their own basic research.

FIRST YEAR AT EOI