page 104

CHAPTER

FOUR

4

Defining the Project

page 105

Select a dream

Use your dream to set a goal

Create a plan

Consider resources

Enhance skills and abilities

Spend time wisely

Start! Get organized and go

. . . it is one of those acro-whatevers, said Pooh.

—Roger E. Allen and Stephen D. Allen, Winnie-the-Pooh on Success (New York: Penguin, 1997), p. 10.

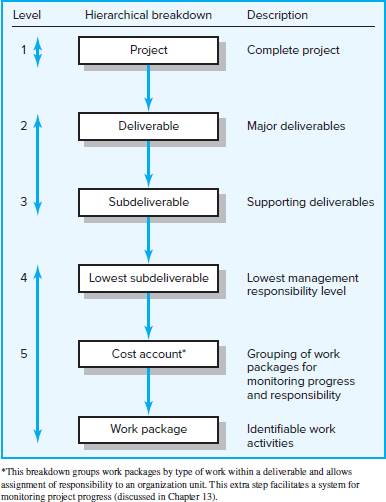

Project managers in charge of a single small project can plan and schedule the project tasks without much formal planning and information. However, when the project page 106manager must manage several small projects or a large, complex project, a threshold is quickly reached in which the project manager can no longer cope with the detail.

This chapter describes a disciplined, structured method for selectively collecting information to use through all phases of the project life cycle, to meet the needs of all stakeholders (e.g., customer, project manager), and to measure performance against the strategic plan of the organization. The suggested method is a selective outline of the project called the work breakdown structure. The early stages of developing the outline ensure that all tasks are identified and that project participants have an understanding of what is to be done. Once the outline and its detail are defined, an integrated information system can be developed to schedule work and allocate budgets. This baseline information is later used for control.

In addition, the chapter presents a variant of the work breakdown structure called the process breakdown structure as well as responsibility matrices that are used for smaller, less complex projects. With the work of the project defined through the work breakdown structure, the chapter concludes with the process of creating a communication plan used to help coordinate project activities and follow progress.

The five generic steps described provide a structured approach for collecting the project information necessary for developing a work breakdown structure. These steps and the development of project networks found in the next chapters all take place concurrently, and several iterations are typically required to develop dates and budgets that can be used to manage the project. The old saying “We can control only what we have planned” is true; therefore, defining the project is the first step.

4.1 Step 1: Defining the Project Scope

Defining the project scope sets the stage for developing a detailed project plan. Project scope is a definition of the end result or mission of your project—a product or service for your client/customer. The primary purpose is to define as clearly as possible the deliverable(s) for the end user and to focus project plans.

Research clearly shows that a poorly defined scope or mission is the most frequently mentioned barrier to project success. In a study involving more than 1,400 project managers in the United States and Canada, Gobeli and Larson (1990) found that approximately 50 percent of the planning problems relate to unclear definition of scope and goals. This and other studies suggest a strong correlation between project success and clear scope definition (Ashley et al., 1987; Pinto & Slevin, 1988; Standish Group, 2009). The scope document directs focus on the project purpose throughout the life of the project for the customer and project participants.

The scope should be developed under the direction of the project manager, customer, and other significant stakeholders. The project manager is responsible for seeing that there is agreement with the owner on project objectives, deliverables at each stage of the project, technical requirements, and so forth. For example, a deliverable in the early stage might be specifications; for the second stage, three prototypes for production; for the third, a sufficient quantity to introduce to market; and finally, marketing promotion and training.

Your project scope definition is a document that will be published and used by the project owner and project participants for planning and measuring project success. Scope describes what you expect to deliver to your customer when the project is complete. Your project scope should define the results to be achieved in specific, tangible, and measurable terms.

page 107

Employing a Project Scope Checklist

Clearly project scope is the keystone interlocking all elements of a project plan. To ensure that scope definition is complete, you may wish to use the following checklist:

| Project Scope Checklist |

|

Project objective. The first step of project scope definition is to define the overall objective to meet your customer’s need(s). For example, as a result of extensive market research a computer software company decides to develop a program that automatically translates verbal sentences in English to Russian. The project should be completed within three years at a cost not to exceed $1.5 million. Another example is to design and construct a portable hazardous-waste thermal treatment system in 13 months at a cost not to exceed $13 million. The project objective answers the questions of what, when, how much, and at times where.

Product scope description. This step is a detailed description of the characteristics of the product, service, or outcome of the project. The description is progressively elaborated throughout the project. The product scope answers the question “What end result is wanted?” For example, if the product is a cell phone, its product scope will be its screen size, battery, processor, camera type, memory, and so on.

Justification. It is important that project team members and stakeholders know why management authorized the project. What is the problem or opportunity the project is addressing? This is sometimes referred to as the business case for the project, since it usually includes cost/benefit analysis and strategic significance. For example, on a new-release project, the justification may be an expected ROI of 30 percent and an enhanced reputation in the marketplace.

Deliverables. The next step is to define major deliverables—the expected, measurable outputs over the life of the project. For example, deliverables in the early design phase of a project might be a list of specifications. In the second phase deliverables might be software coding and a technical manual. The next phase might be the prototype. The final phase might be final tests and approved software. Note: Deliverables and requirements are often used interchangeably.

Milestones. A milestone is a significant event in a project that occurs at a point in time. The milestone schedule shows only major segments of work; it represents first, rough-cut estimates of time, cost, and resources for the project. The milestone schedule is built using the deliverables as a platform to identify major segments of work and an end date—for example, testing complete and finished by July 1 of the same year. Milestones should be natural, important control points in the project. Milestones should be easy for all project participants to recognize.

page 108

Technical requirements. More frequently than not, a product or service will have technical requirements to ensure proper performance. Technical requirements typically clarify the deliverables or define the performance specifications. For example, a technical requirement for a personal computer might be the ability page 109to accept 120-volt alternating current or 240-volt direct current without any adapters or user switches. Another well-known example is the ability of 911 emergency systems to identify the caller’s phone number and the location of the phone. Examples from information systems projects include the speed and capacity of database systems and connectivity with alternative systems. For understanding the importance of key requirements, see Snapshot from Practice 4.1: Big Bertha ERC II versus the USGA’s COR Requirement.

Limits and exclusions. The limits of scope should be defined. Failure to do so can lead to false expectations and to expending resources and time on the wrong problem. The following are examples of limits: work on-site is allowed only page 110between the hours of 8:00 p.m. and 5:00 a.m.; system maintenance and repair will be done only up to one month after final inspection; and the client will be billed for additional training beyond that prescribed in the contract. Exclusions further define the boundary of the project by stating what is not included. Examples include: data will be collected by the client, not the contractor; a house will be built, but no landscaping or security devices added; software will be installed, but no training given.

Acceptance criteria. Acceptance criteria are a set of conditions that must be met before the deliverables are accepted. The following are examples: all tasks and milestones are complete, new service processes begin with a less than 1 percent defect rate, third-party certification is required, and customer on-site inspection is required.

Scope statements are twofold. There is a short, one- to two-page summary of key elements of the scope, followed by extended documentation of each element (e.g., a detailed milestone schedule or risk analysis report). See Snapshot from Practice 4.2: Scope Statement for an example of a summary page.

The project scope checklist in Step 1 is generic. Different industries and companies will develop unique checklists and templates to fit their needs and specific kinds of projects. A few companies engaged in contracted work refer to scope statements as “statements of work (SOWs).” Other organizations use the term project charter. However, the term project charter has emerged to have a special meaning in the world of project management. A project charter is a document that authorizes the project manager to initiate and lead the project. This document is issued by upper management and provides the project manager with written authority to use organizational resources for project activities. Often the charter will include a brief scope description as well as such items as risk limits, business case, spending limits, and even team composition.

Many projects suffer from scope creep, which is the tendency for the project scope to expand over time—usually by changing requirements, specifications, and priorities. Scope creep can have a positive or negative effect on the project, but in most cases scope creep means added costs and possible project delays. Changes in requirements, specifications, and priorities frequently result in cost overruns and delays. Examples are abundant—the Denver Airport baggage handling system, Boston’s new freeway system (“The Big Dig”), the Sochi Winter Olympics, and the list goes on. On software development projects, scope creep is manifested in bloated products in which added functionality undermines ease of use.

Five of the most common causes of scope creep are

Poor requirement analysis. Customers often don’t really know what they want. “I’ll know it when I see it” syndrome contributes to wasted effort and ambiguity.

Not involving users early enough. Too often project teams think they know up front what the end user needs, only to find out later they were mistaken.

Underestimating project complexity. Complexity and associated uncertainty naturally lead to changes in scope, since there are so many unknowns yet to be discovered.

Lack of change control. A robust change control process is needed to ensure that only appropriate changes occur in the scope of the project.

page 111Gold plating. Gold plating refers to adding extra value to the project that is beyond the scope of the project. This is common on software projects where developers add features that they think the end user will like.

In many cases these causes reflect a misfit—traditional project management methods being applied to high-uncertainty projects (remember Figure 1.2!). Instead of trying to establish plans up front, Agile project management should be applied to discover what needs to be done. On Agile projects the scope is assumed to evolve rather than be prescribed. Scope creep is managed and reflects progress.

If the project scope needs to change, it is critical to have a sound change control process in place that records the change and keeps a log of all project changes. Change control is one of the topics of Chapter 7. Project managers in the field constantly suggest that dealing with changing requirements is one of their most challenging problems.

4.2 Step 2: Establishing Project Priorities

Quality and the ultimate success of a project are traditionally defined as meeting and/or exceeding the expectations of the customer and/or upper management in terms of the cost (budget), time (schedule), and performance (scope) of the project (see Figure 4.1). The interrelationship among these criteria varies. For example, sometimes it is necessary to compromise the performance and scope of the project to get the project done quickly or less expensively. Often the longer a project takes, the more expensive it becomes. However, a positive correlation between cost and schedule may not always be true. Other times project costs can be reduced by using cheaper, less efficient labor or equipment that extends the duration of the project. Likewise, as will be seen in Chapter 9, project managers are often forced to expedite, or “crash,” certain key activities by adding additional labor, thereby raising the original cost of the project.

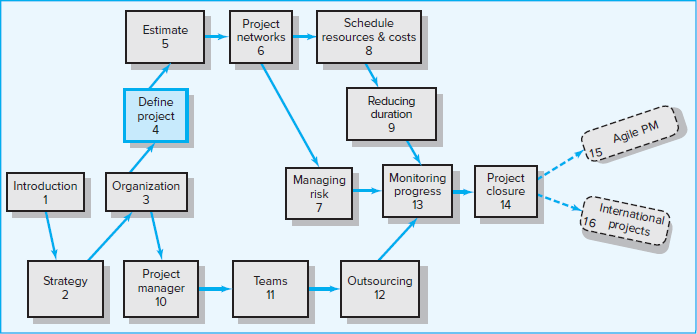

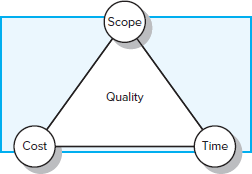

FIGURE 4.1

Project Management Trade-offs

One of the primary jobs of a project manager is to manage the trade-offs among time, cost, and performance. To do so, project managers must define and understand the nature of the priorities of the project. They need to have a candid discussion with the project customer and upper management to establish the relative importance of each criterion. For example, what happens when the customer keeps adding requirements? Or if midway through the project a trade-off must be made between cost and expediting, which criterion has priority?

page 112

One technique that is useful for this purpose is completing a priority matrix for the project to identify which criterion is constrained, which should be enhanced, and which can be accepted:

Constrain. The original parameter is fixed. The project must meet the completion date, specifications and scope of the project, or budget.

Enhance. Given the scope of the project, which criterion should be optimized? In the case of time and cost, this usually means taking advantage of opportunities to either reduce costs or shorten the schedule. Conversely, with regard to performance, enhancing means adding value to the project.

Accept. For which criterion is it tolerable not to meet the original parameters? When trade-offs have to be made, is it permissible to allow the schedule to slip, to reduce the scope and performance of the project, or to go over budget?

Figure 4.2 displays the priority matrix for the development of a new wireless router. Because time-to-market is important to sales, the project manager is instructed to take advantage of every opportunity to reduce completion time. In doing so, going over budget is acceptable, though not desirable. At the same time, the original performance specifications for the router as well as reliability standards cannot be compromised.

FIGURE 4.2

Project Priority Matrix

Priorities vary from project to project. For example, for many software projects time-to-market is critical, and companies like Microsoft may defer original scope requirements to later versions in order to get to the market first. Alternatively, for special event projects (conferences, parades, tournaments) time is constrained once the date has been announced, and if the budget is tight the project manager will compromise the scope of the project in order to complete the project on time.

Some would argue that all three criteria are always constrained and that good project managers should seek to optimize each criterion. If everything goes well on a project and no major problems or setbacks are encountered, their argument may be valid. However, this situation is rare, and project managers are often forced to make tough decisions that benefit one criterion while compromising the other two. The purpose of this exercise is to define and agree on what the priorities and constraints of the project are so that when “push comes to shove,” the right decisions can be made.

There are likely to be natural limits to the extent managers can constrain, enhance, or accept any one criterion. It may be acceptable for the project to slip one month page 113behind schedule but no further or to exceed the planned budget by as much as $20,000. Likewise, it may be desirable to finish a project a month early, but after that cost conservation should be the primary goal. Some project managers document these limits as part of creating the priority matrix.

In summary, developing a priority matrix for a project before the project begins is a useful exercise. It provides a forum for clearly establishing priorities with customers and top management so as to create shared expectations and avoid misunderstandings. The priority information is essential to the planning process, where adjustments can be made in the scope, schedule, and budget allocation. Finally, the matrix is useful midway in the project for approaching a problem that must be solved.

One caveat must be mentioned; during the course of a project, priorities may change. The customer may suddenly need the project completed one month sooner, or new directives from top management may emphasize cost-saving initiatives. The project manager needs to be vigilant in order to anticipate and confirm changes in priorities and make appropriate adjustments.

4.3 Step 3: Creating the Work Breakdown Structure

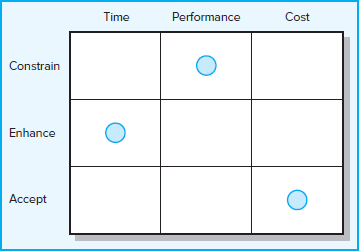

Major Groupings in a WBS

Once the scope and deliverables have been identified, the work of the project can be successively subdivided into smaller and smaller work elements. The outcome of this hierarchical process is called the work breakdown structure (WBS). Use of a WBS helps to assure project managers that all products and work elements are identified, to integrate the project with the current organization, and to establish a basis for control. Basically, the WBS is an outline of the project with different levels of detail.

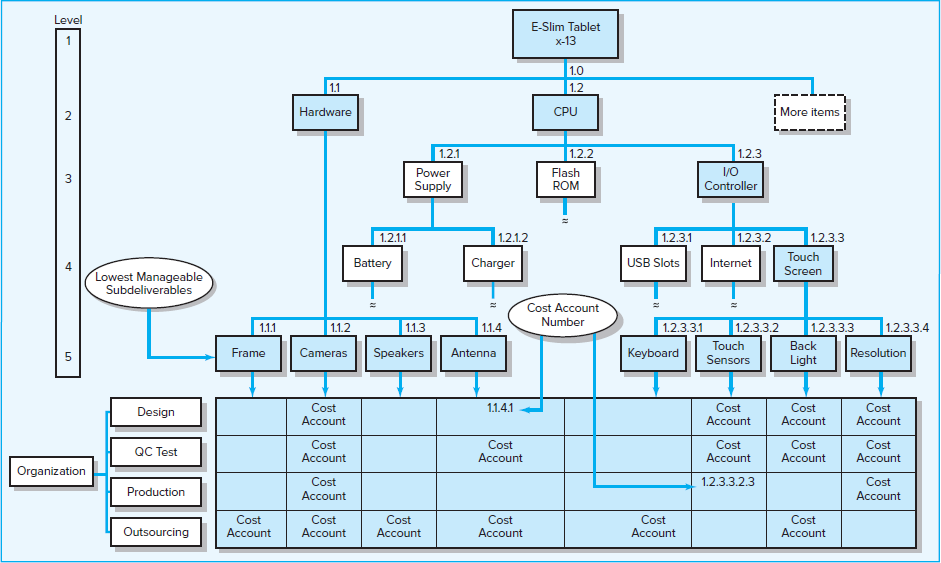

Figure 4.3 shows the major groupings commonly used in the field to develop a hierarchical WBS. The WBS begins with the project as the final deliverable. Major project work deliverables/systems are identified first; then the subdeliverables necessary to accomplish the larger deliverables are defined. The process is repeated until the subdeliverable detail is small enough to be manageable and one person can be responsible. This subdeliverable is further divided into work packages. Because the lowest subdeliverable usually includes several work packages, the work packages are grouped by type of work—for example, design and testing. These groupings within a subdeliverable are called cost accounts. This grouping facilitates a system for monitoring project progress by work, cost, and responsibility.

FIGURE 4.3

Hierarchical Breakdown of the WBS

How a WBS Helps the Project Manager

The WBS defines all the elements of the project in a hierarchical framework and establishes their relationships to the project end item(s). Think of the project as a large work package that is successively broken down into smaller work packages; the total project is the summation of all the smaller work packages. This hierarchical structure facilitates the evaluation of cost, time, and technical performance at all levels in the organization over the life of the project. The WBS also provides management with information appropriate to each level. For example, top management deals primarily with major deliverables, while first-line supervisors deal with smaller subdeliverables and work packages.

page 114

Each item in the WBS needs a time and cost estimate. With this information it is possible to plan, schedule, and budget the project. The WBS also serves as a framework for tracking cost and work performance.

As the WBS is developed, organization units and individuals are assigned responsibility for executing work packages. This integrates the work and the organization. In practice, this process is sometimes called the organization breakdown structure (OBS), which will be further discussed later in the chapter.

Use of the WBS provides the opportunity to “roll up” (sum) the budget and actual costs of the smaller work packages into larger work elements so that performance can be measured by organization units and work accomplishment.

The WBS can also be used to define communication channels and assist in understanding and coordinating many parts of the project. The structure shows the work and responsible organization units and suggests where written communication should be directed. Problems can be quickly addressed and coordinated because the structure integrates work and responsibility.

A Simple WBS Development

Figure 4.4 shows a simplified WBS to develop a new prototype tablet computer. At the top of the chart (level 1) is the project end item—the E-Slim Tablet x-13 Prototype. The subdeliverable levels page 115(2–5) below level 1 represent further decomposition of work. The levels of the structure can also represent information for different levels of management. For example, level 1 information represents the total project objective and is useful to top management; levels 2, 3, and 4 are suitable for middle management; and level 5 is for first-line managers.

FIGURE 4.4 Work Breakdown Structure

page 116

In Figure 4.4, level 2 indicates there are two major deliverables—Hardware and CPU, or central processing unit. (There are likely to be other major deliverables such as software, but for illustrative purposes we are limiting our focus to just two major deliverables.) At level 3, the CPU is connected to three deliverables—Power Supply, Flash ROM, and I/O Controller. I/O Controller has three subdeliverables at level 4—USB Slots, Internet, and Touch Screen. The many subdeliverables for USB Slots and Internet have not been decomposed. Touch Screen (shaded) has been decomposed down to level 5 and to the work package level.

Note that level 2, Hardware, skips levels 3 and 4 because the final subdeliverables can be pushed down to the lowest manageable level 5; skipping levels 3 and 4 suggests little coordination is needed and skilled team members are already familiar with the work needed to complete the level 5 subdeliverables. For example, Hardware requires four subdeliverables at level 5—Frame, Cameras, Speakers, and Antenna. Each subdeliverable includes work packages that will be completed by an assigned organization unit. Observe that the Cameras subdeliverable includes four work packages—WP-C1, 2, 3, and 4. Back Light, a subdeliverable of Touch Screen, includes three work packages—WP-L 1, 2, and 3.

The lowest level of the WBS is called a work package. Work packages are short-duration tasks that have a definite start and stop point, consume resources, and represent cost. Each work package is a control point. A work package manager is responsible for seeing that the package is completed on time, within budget, and according to technical specifications. Practice suggests a work package should not exceed 10 workdays or one reporting period. If a work package has a duration exceeding 10 days, check or monitoring points should be established within the duration—say, every three to five days—so progress and problems can be identified before too much time has passed. Each work package of the WBS should be as independent of other packages of the project as possible. No work package is described in more than one subdeliverable of the WBS.

There is an important difference from start to finish between the last work breakdown subdeliverable and a work package. Typically a work breakdown subdeliverable includes the outcomes of more than one work package from perhaps two or three departments. Therefore, the subdeliverable does not have a duration of its own and does not consume resources or cost money directly. (In a sense, of course, a duration for a particular work breakdown element can be derived from identifying which work package must start first [earliest] and which package will be the latest to finish; the difference from start to finish becomes the duration for the subdeliverable.) The higher elements are used to identify deliverables at different phases in the project and to develop status reports during the execution stage of the project life cycle. Thus, the work package is the basic unit used for planning, scheduling, and controlling the project.

In summary, each work package in the WBS

Defines work (what).

Identifies time to complete a work package (how long).

Identifies a time-phased budget to complete a work package (cost).

Identifies resources needed to complete a work package (how much).

Identifies a single person responsible for units of work (who).

Identifies monitoring points for measuring progress (how well).

page 117

Creating a WBS from scratch can be a daunting task. Project managers should take advantage of relevant examples from previous projects to begin the process.

WBSs are products of group efforts. If the project is small, the entire project team may be involved in breaking down the project into its components. For large, complex projects, the people responsible for the major deliverables are likely to meet to establish the first two levels of deliverables. In turn, further detail would be delegated to the people responsible for the specific work. Collectively this information would be gathered and integrated into a formal WBS by a project support person. The final version would be reviewed by the inner echelon of the project team. Relevant stakeholders (most notably customers) would be consulted to confirm agreement and revise when appropriate.

Project teams developing their first WBS frequently forget that the structure should be end-item, output oriented. First attempts often result in a WBS that follows the organization structure—design, marketing, production, finance. If a WBS follows the organization structure, the focus will be on the organization function and processes, rather than the project output or deliverables. In addition, a WBS with a process focus will become an accounting tool that records costs by function rather than a tool for “output” management. Every effort should be made to develop a WBS that is output oriented in order to concentrate on concrete deliverables. See Snapshot from Practice 4.3: Creating a WBS.

page 118

4.4 Step 4: Integrating the WBS with the Organization

The WBS is used to link the organization units responsible for performing the work. In practice, the outcome of this process is the organization breakdown structure (OBS). The OBS depicts how the firm has organized to discharge work responsibility. The purposes of the OBS are to provide a framework to summarize organization unit work performance, identify the organization units responsible for work packages, and tie the organization unit to cost control accounts. Recall that, cost accounts group similar work packages (usually under the purview of a department). The OBS defines the organization subdeliverables in a hierarchical pattern in successively smaller and smaller units. Frequently the traditional organization structure can be used. Even if the project is completely performed by a team, it is necessary to break down the team structure for assigning responsibility for budgets, time, and technical performance.

As in the WBS, the OBS assigns the lowest organization unit the responsibility for work packages within a cost account. Herein lies one major strength of using the WBS and OBS; they can be integrated as shown in Figure 4.5. The intersection of work packages and the organization unit creates a project control point (cost account) that integrates work and responsibility. For example, at level 5, Touch Sensors has three work packages that have been assigned to the Design, Quality Control Test, and Production Departments. The intersection of the WBS and OBS represents the set of work packages necessary to complete the subdeliverable located immediately above and the organization unit on the left responsible for accomplishing the packages at the intersection. Note that the Design Department is responsible for five different work packages across the Hardware and Touch Screen deliverables.

Later we will use the intersection as a cost account for management control of projects. For example, the Cameras element requires the completion of work packages whose primary responsibility will include the Design, QC Test, Production, and Outsourcing Departments. Control can be checked from two directions—outcomes and responsibility. In the execution phase of the project, progress can be tracked vertically on deliverables (client’s interest) and tracked horizontally by organization responsibility (owner’s interest).

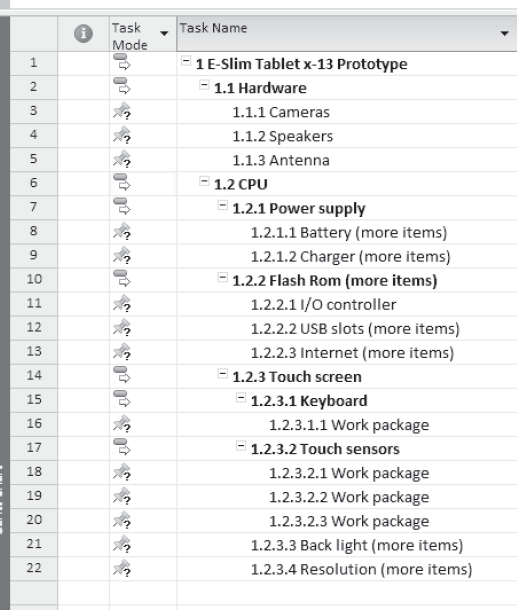

4.5 Step 5: Coding the WBS for the Information System

Gaining the maximum usefulness of a breakdown structure depends on a coding system. The codes are used to define levels and elements in the WBS, organization elements, work packages, and budget and cost information. The codes allow reports to be consolidated at any level in the structure. The most commonly used scheme in practice is numeric indention. A portion of the E-Slim Tablet x-13 Prototype project is presented in Exhibit 4.1.

Note that the project identification is 1.0. Each successive indention represents a lower element or work package. Ultimately the numeric scheme reaches down to the work package level, and all tasks and elements in the structure have an identification code. The “cost account” is the focal point because all budgets, work assignments, time, cost, and technical performance come together at this point.

This coding system can be extended to cover large projects. Additional schemes can be added for special reports. For example, adding a “23” after the code could indicate a site location, an elevation, or a special account such as labor. Some letters can be used as special identifiers such as “M” for materials or “E” for engineers.

page 119

FIGURE 4.5 Integration of WBS and OBS

page 120

EXHIBIT 4.1

Coding the WBS

Source: Microsoft Excel

You are not limited to only 10 subdivisions (0–9); you can extend each subdivision to large numbers—for example, .1–.99 or .1–.9999. If the project is small, you can use whole numbers. The following example is from a large, complex project:

3R−237A−P2−33.6

where 3R identifies the facility, 237A represents elevation and the area, P2 represents pipe 2 inches wide, and 33.6 represents the work package number. In practice most organizations are creative in combining letters and numbers to minimize the length of WBS codes.

On larger projects, the WBS is further supported with a WBS dictionary that provides detailed information about each element in the WBS. The dictionary typically includes the work package level (code), name, and functional description. In some cases the description is supported with specifications. The availability of detailed descriptions has an added benefit of dampening scope creep.

page 121

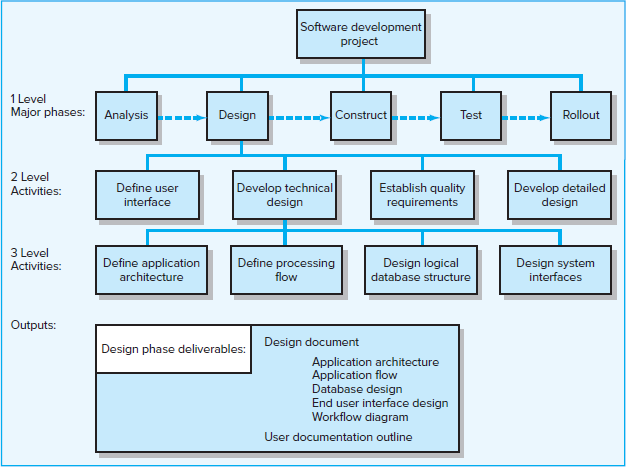

4.6 Process Breakdown Structure

The WBS is best suited for design and build projects that have tangible outcomes such as an offshore mining facility or a new car prototype. The project can be decomposed, or broken down, into major deliverables, subdeliverables, further subdeliverables, and ultimately work packages. It is more difficult to apply WBS to less tangible, process-oriented projects in which the final outcome is a product of a series of steps or phases. Here, the big difference is that the project evolves over time with each phase affecting the next phase. Information systems projects typically fall in this category—for example, creating an extranet website or an internal software database system. Process projects are driven by performance requirements, not by plans/blueprints. Some practitioners choose to utilize a process breakdown structure (PBS) instead of the classic WBS.

Figure 4.6 provides an example of a PBS for a software development project. Instead of being organized around deliverables, the project is organized around phases. Each of the five major phases can be broken down into more specific activities until a sufficient level of detail is achieved to communicate what needs to be done to complete that phase. People can be assigned to specific activities, and a complementary OBS can be created, just as is done for the WBS. Deliverables are not ignored but are defined as outputs required to move to the next phase. The software industry often refers to a PBS as the “waterfall method,” since progress flows downward through each phase.1

FIGURE 4.6 PBS for Software Development Project

page 122

Checklists that contain the phase exit requirements are developed to manage project progress. These checklists provide the means to support phase walk-throughs and reviews. Checklists vary depending upon the project and activities involved but typically include the following details:

Deliverables needed to exit a phase and begin a new one.

Quality checkpoints to ensure that deliverables are complete and accurate.

Sign-offs by all responsible stakeholders to indicate that the phase has been successfully completed and that the project should move on to the next phase.

As long as exit requirements are firmly established and deliverables for each phase are well defined, the PBS provides a suitable alternative to the standard WBS for projects that involve extensive development work.

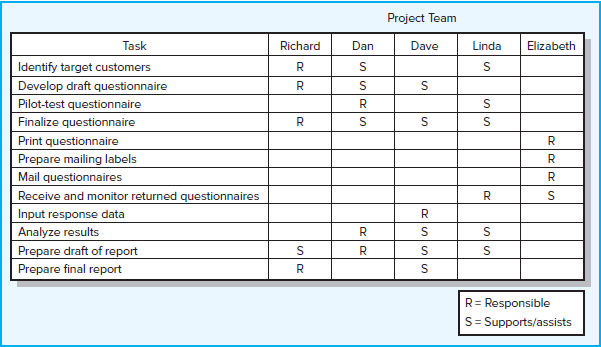

4.7 Responsibility Matrices

In many cases, the size and scope of the project do not warrant an elaborate WBS or OBS. One tool that is widely used by project managers and task force leaders of small projects is the responsibility matrix (RM). The RM (sometimes called a linear responsibility chart) summarizes the tasks to be accomplished and who is responsible for what on a project. In its simplest form an RM consists of a chart listing all the project activities and the participants responsible for each activity. For example, Figure 4.7 illustrates an RM for a market research study. In this matrix the R is used to identify the committee member who is responsible for coordinating the efforts of other team members assigned to the task and making sure that the task is completed. The S is used to identify members of the five-person team who will support and/or assist the individual responsible. Simple RMs like this one are useful not only for organizing and assigning responsibilities for small projects but also for subprojects of large, more complex projects.

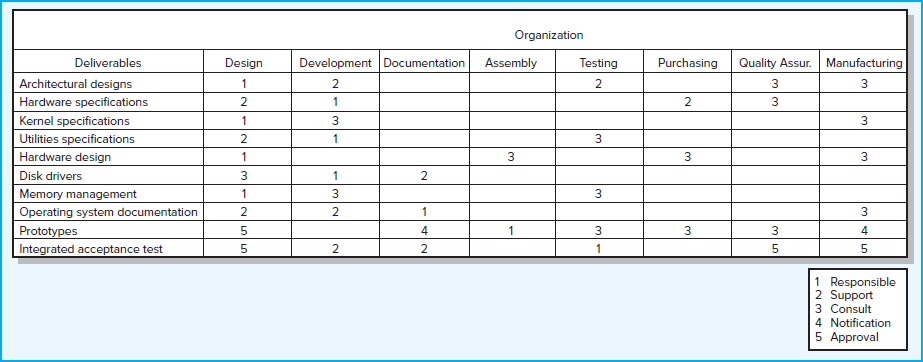

More complex RMs not only identify individual responsibilities but also clarify critical interfaces between units and individuals that require coordination. For example, Figure 4.8 is an RM for a larger, more complex project to develop a new piece of page 123automated equipment. Notice that within each cell a numeric coding scheme is used to define the nature of involvement on that specific task. Such an RM extends the WBS/OBS and provides a clear and concise method for depicting responsibility, authority, and communication channels.

FIGURE 4.7 Responsibility Matrix for a Market Research Project

FIGURE 4.8 Responsibility Matrix for the Conveyor Belt Project

page 124

Responsibility matrices provide a means for all participants in a project to view their responsibilities and agree on their assignments. They also help clarify the extent or type of authority exercised by each participant in performing an activity in which two or more parties have overlapping involvement. By using an RM and by defining authority, responsibility, and communications within its framework, the relationship between different organization units and the work content of the project is made clear.

4.8 Project Communication Plan

Once the project deliverables and work are clearly identified, creating an internal communication plan is vital. Stories abound of poor communication as a major contributor to project failure. Having a robust communication plan can go a long way toward mitigating project problems and can ensure that customers, team members, and other stakeholders have the information to do their jobs.

The communication plan is usually created by the project manager and/or the project team in the early stage of project planning.

Communication is a key component in coordinating and tracking project schedules, issues, and action items. The plan maps out the flow of information to different stakeholders and becomes an integral part of the overall project plan. The purpose of a project communication plan is to express what, who, how, and when information will be transmitted to project stakeholders so schedules, issues, and action items can be tracked.

Project communication plans address the following core questions:

What information needs to be collected and when?

Who will receive the information?

What methods will be used to gather and store information?

What are the limits, if any, on who has access to certain kinds of information?

When will the information be communicated?

How will it be communicated?

Developing a communication plan that answers these questions usually entails the following basic steps:

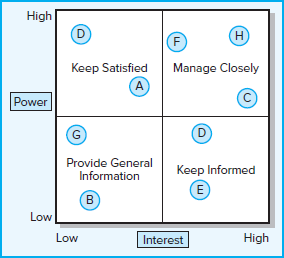

Stakeholder analysis. Identify the target groups. Typical groups could be the customer, sponsor, project team, project office, or anyone else who needs project information to make decisions and/or contribute to project progress. A common tool found in practice to initially identify and analyze major project stakeholders’ communication needs is presented in Figure 4.9.2 What is communicated and how are influenced by stakeholder interest and power. Some of these stakeholders may have the power to either block or enhance your project. By identifying stakeholders and prioritizing them on the “Power/Interest” map, you can plan the type and frequency of communications needed. (More on stakeholders will be discussed in Chapter 10.) page 125For example, on a typical project you want to manage closely the professionals doing the work, while you want to satisfy senior management and the project sponsor with periodic updates. Unions and operation managers interested in capacity should be kept informed, while you would only need to provide general information to the legal, public relations, and other departments.

FIGURE 4.9

Stakeholder Communications

Information needs. What information is pertinent to stakeholders who contribute to the project’s progress? The simplest answer to this question can be obtained by asking the various individuals what information they need and when they need it. For example, top management needs to know how the project is progressing, whether it is encountering critical problems, and the extent to which project goals are being realized. This information is required so that they can make strategic decisions and manage the portfolio of projects. Project team members need to see schedules, task lists, specifications, and the like so they know what needs to be done next. External groups need to know any changes in the schedule and performance requirements of the components they are providing. Frequent information needs found in communication plans are

Project status reports Deliverable issues Changes in scope Team status meetings Gating decisions Accepted request changes Action items Milestone reports Sources of information. When the information needs are identified, the next step is to determine the sources of information. That is, where does the information reside? How will it be collected? For example, information relating to the milestone report, team meetings, and project status meetings would be found in the minutes and reports of various groups.

Dissemination modes. In today’s world, traditional status report meetings are being supplemented by e-mail, teleconferencing, SharePoint, and a variety of database sharing programs to circulate information. In particular, many companies are using the Web to create a “virtual project office” to store project information. Project management software feeds information directly to the website so that different people have immediate access to relevant project information. In some cases appropriate information is routed automatically to key stakeholders. Backup paper hardcopy to specific stakeholders is still critical for many project changes and action items.

page 126

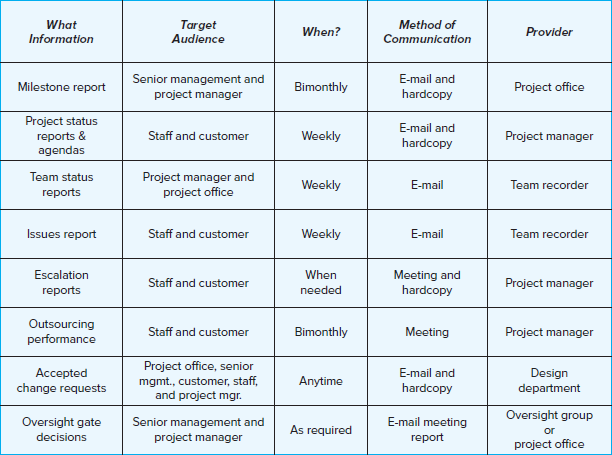

FIGURE 4.10 Shale Oil Research Project Communication Plan

Responsibility and timing. Determine who will send out the information. For example, a common practice is to have secretaries of meetings forward the minutes or specific information to the appropriate stakeholders. In some cases the responsibility lies with the project manager or project office. Timing and frequency of distribution appropriate to the information need to be established.

The advantage of establishing a communication plan is that instead of responding to information requests, you are controlling the flow of information. This reduces confusion and unnecessary interruptions, and it can provide project managers greater autonomy. Why? By reporting on a regular basis how things are going and what is happening, you allow senior management to feel more comfortable about letting the team complete the project without interference. See Figure 4.10 for a sample Shale Oil research project communication plan.

The importance of establishing a plan up front for communicating important project information cannot be overstated. Many of the problems that plague a project can be traced back to insufficient time devoted to establishing a well-grounded internal communication plan.

Summary

The project scope definition, priorities, and work breakdown structure are the keys to nearly every aspect of managing the project. The scope definition provides focus and emphasis on the end item(s) of the project. Establishing project priorities allows managers to make appropriate trade-off decisions. The WBS structure helps ensure that all tasks of the project are identified and provides two views of the project—one on deliverables and one on organization responsibility. The WBS avoids having the project driven page 127by organization function or by a finance system. The structure forces attention to realistic requirements of personnel, hardware, and budgets. Use of the structure provides a powerful framework for project control that identifies deviations from the plan, identifies responsibility, and spots areas for improved performance. No well-developed project plan or control system is possible without a disciplined, structured approach. The WBS, OBS, and cost account codes provide this discipline. The WBS serves as the database for developing the project network, which establishes the timing of work, people, equipment, and costs.

The PBS is often used for process-based projects with ill-defined deliverables. In small projects responsibility matrices may be used to clarify individual responsibility.

Clearly defining your project is the first and most important step in planning. The absence of a clearly defined project plan consistently shows up as the major reason for project failures. Whether you use a WBS, PBS, or responsibility matrix will depend primarily on the size and nature of your project. Whatever method you use, definition of your project should be adequate to allow for good control as the project is being implemented. Follow-up with a clear communication plan for coordinating and tracking project progress will help you keep important stakeholders informed and avoid some potential problems.

Key Terms

Review Questions

What are the eight elements of a typical scope statement?

What questions does a project objective answer? What would be an example of a good project objective?

What does it mean if the priorities of a project include Time-constrain, Scope-accept, and Cost-enhance?

What kinds of information are included in a work package?

When would it be appropriate to create a responsibility matrix rather than a full-blown WBS?

How does a communication plan benefit the management of projects?

SNAPSHOT  FROM PRACTICE

FROM PRACTICE

Discussion Questions

4.1 Big Bertha ERC II versus the USGA’s COR Requirement

How did Helmstetter’s vision conflict with USGA rules?

How could this mistake have been avoided?

4.3 Creating a WBS

Why is it important that final activities not be open-ended?

page 128

Exercises

You are in charge of organizing a dinner-dance concert for a local charity. You have reserved a hall that will seat 30 couples and have hired a jazz combo.

Develop a scope statement for this project that contains examples of all the elements. Assume that the event will occur in four weeks. Provide your best estimate of the dates for milestones.

What would the priorities likely be for this project?

In small groups, identify real-life examples of a project that would fit each of the following priority scenarios:

Time-constrain, Scope-enhance, Cost-accept

Time-accept, Scope-constrain, Cost-accept

Time-constrain, Scope-accept, Cost-enhance

Develop a WBS for a project in which you are going to build a bicycle. Try to identify all of the major components and provide three levels of detail.

You are the father or mother of a family of four (kids ages 13 and 15) planning a weekend camping trip. Develop a responsibility matrix for the work that needs to be done prior to starting your trip.

Develop a WBS for a local stage play. Be sure to identify the deliverables and organization units (people) responsible. How would you code your system? Give an example of the work packages in one of your cost accounts. Develop a corresponding OBS that identifies who is responsible for what.

Use an example of a project you are familiar with or are interested in. Identify the deliverables and organization units (people) responsible. How would you code your system? Give an example of the work packages in one of your cost accounts.

Develop a communication plan for an airport security project. The project entails installing the hardware and software system that (1) scans a passenger’s eyes, (2) fingerprints the passenger, and (3) transmits the information to a central location for evaluation.

Go to an Internet search engine (e.g., Google) and type in “project communication plan.” Check three or four results that have “.gov” as their source. How are they similar or dissimilar? What would be your conclusion concerning the importance of an internal communication plan?

Your roommate is about to submit a scope statement for a spring concert sponsored by the entertainment council at Western Evergreen State University (WESU). WESU is a residential university with over 22,000 students. This will be the first time in six years that WESU has sponsored a spring concert. The entertainment council has budgeted $40,000 for the project. The event is to occur on June 5. Since your roommate knows you are taking a class on project management she has asked you to review her scope statement and make suggestions for improvement. She considers the concert a resume-building experience and wants to be as professional as possible. Following is a draft of her scope statement. What suggestions would you make and why?

WESU Spring Music Concert

Project Objective

To organize and deliver a 6-hour music concert

Product Scope Description

An all-age, outdoor rock concert

page 129

Justification

Provide entertainment to WESU community and enhance WESU’s reputation as a destination university

Deliverables

Concert security

Contact local newspapers and radio stations

Separate beer garden

Six hours of musical entertainment

Design a commemorative concert T-shirt

Local sponsors

Food venues

Event insurance

Safe environment

Milestones

Secure all permissions and approvals

Sign big-name artist

Contact secondary artists

Secure vendor contracts

Advertising campaign

Plan set-up

Concert

Clean-up

Technical Requirements

Professional sound stage and system

At least five performing acts

Restroom facilities

Parking

Compliance with WESU and city requirements/ordinances

Limits and Exclusions

Seating capacity for 8,000 students

Performers are responsible for travel arrangement to and from WESU

Performers must provide own liability insurance

Performers and security personnel will be provided lunch and dinner on the day of the concert

Vendors contribute 25 percent of sales to concert fund

Concert must be over at 12:15 a.m.

Customer Review: WESU

References

Ashley, D. B., et al., “Determinants of Construction Project Success,” Project Management Journal, vol. 18, no. 2 (June 1987), p. 72.

Chilmeran, A. H., “Keeping Costs on Track,” PM Network, 2004 pp. 45–51.

Gary, L., “Will Project Scope Cost You—or Create Value?” Harvard Management Update, January 2005.

Gobeli, D. H., and E. W. Larson, “Project Management Problems,” Engineering Management Journal, vol. 2 (1990), pp. 31–36.

Ingebretsen, M., “Taming the Beast,” PM Network, July 2003, pp. 30–35.

Katz, D. M., “Case Study: Beware ‘Scope Creep’ on ERP Projects,” CFO.com, March 27, 2001.

Kerzner, H., Project Management: A Systems Approach to Planning, 8th ed. (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 2003).

page 130

Luby, R. E., D. Peel, and W. Swahl, “Component-Based Work Breakdown Structure,” Project Management Journal, vol. 26, no. 2 (December 1995), pp. 38–44.

Murch, R., Project Management: Best Practices for IT Professionals (Upper Darby, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001).

Pinto, J. K., and D. P. Slevin, “Critical Success Factors across the Project Life Cycle,” Project Management Journal, vol. 19, no. 3 (June 1988), p. 72.

Pitagorsky, G., “Realistic Project Planning Promotes Success,” Engineer’s Digest, vol. 29, no. 1 (2001).

PMI Standards Committee, Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (Newton Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2017).

Posner, B. Z., “What It Takes to Be a Good Project Manager,” Project Management Journal, vol. 18, no. 1 (March 1987), p. 52.

Raz, T., and S. Globerson, “Effective Sizing and Content Definition of Work Packages,” Project Management Journal, vol. 29, no. 4 (1998), pp. 17–23.

The Standish Group, CHAOS Summary 2009, pp. 1–4.

Tate, K., and K. Hendrix, “Chartering IT Projects,” Proceedings, 30th Annual, Project Management Institute (Philadelphia: Project Management Institute, 1999), CD.

Case 4.1

Celebration of Colors 5K

Brandon was having an ale with his girlfriend, Sierra, when the subject of the Omega Theta Pi 5K-run project came up. Brandon has been chosen to chair the 5K-charity run for his fraternity. At the time, Brandon thought it would look good on his resume and wouldn’t be too difficult to pull off. This would be the first running event Omega Theta Pi had organized. In the past Delta Tau Chi always organized the spring running event. However, Delta Tau had been dissolved after a highly publicized hazing scandal.

Brandon and his brothers at Omega Theta Pi thought that organizing a 5K-run would be a lot more fun and profitable than the normal spring cleaning service they offered the local community. Early on in the discussions, everyone agreed that partnering with a sorority would be an advantage. Not only would they help manage the event, but they would have useful contacts to recruit sponsors and participants. Brandon pitched the fund raising idea to the sisters at Delta Nu, and they agreed to co-manage the event. Olivia Pomerleau volunteered and was named co-chair by Delta Nu.

Brandon told Sierra about the task force’s first meeting, which was held last night and included five members from each living group. Olivia and Brandon tried, but failed, to meet beforehand due to scheduling conflicts. The meeting began with the attendees introducing themselves and telling what experience they had had with running events. Only one person had not run at past events, but no one had been involved in managing an event other than volunteering as intersection flaggers.

page 131

Olivia then said she thought the first thing they should decide on was the theme of the 5K-race. Brandon hadn’t thought much about this, but everyone agreed that the race had to have a theme. People began to suggest themes and ideas based on other runs they knew about. The group seemed stumped when Olivia said, “Do you know that the last Friday in March is a full moon? In India, Holi, the celebration of colors, occurs on the last full moon in March. Maybe you’ve seen pictures of this, but this is where people go crazy tossing dye and color water balloons at each other. I looked it up and the Holi festival signifies a victory of good over evil, the arrival of spring and the end of winter. It is a day to meet others, play, laugh, and forgive and forget. I think it would be neat if we organized our 5K-run as a Holi festival. At different points in the race we would have people toss dye on runners. The run would end with a giant water balloon fight. We could even see if Evergreen [the local Indian restaurant] would cater the event!”

Brandon and the other boys looked at each other, while the girls immediately supported the idea. The deal maker occurred when Olivia showed a YouTube video of a similar event last year at a university in Canada that had over 700 participants and raised over $14,000.

Once the theme was decided the discussion turned into a free-for-all of ideas and suggestions. One member said she may know an artist who could create really neat T-shirts for the event. Others wondered where you get the dye and if it is safe. Another talked about the importance of a website and creating a digital account for registration. Others began to argue whether the run should be done on campus or through the streets of their small college town. One by one students excused themselves due to other commitments. With only a few members remaining Brandon and Olivia adjourned the meeting.

While Brandon took a sip of his IPA beer, Sierra pulled a book out of her knapsack. “Sounds like what you need to do is create what my project management professor calls a WBS for your project.” She pointed to a page in her project management textbook showing a diagram of a WBS.

Make a list of the major deliverables for the 5k-run color project and use them to develop a draft of the work breakdown structure for the project that contains, when appropriate, at least three levels of detail.

How would developing a WBS alleviate some of the problems that occurred during the first meeting and help Brandon organize and plan the project?

Case 4.2

The Home Improvement Project

Lukas Nelson and his wife, Anne, and their three daughters had been living in their house for over five years when they decided it was time to make some modest improvements. One area they both agreed needed an upgrade was the bathtub. Their current house had one standard shower/bathtub combination. Lukas was 6 feet four and could barely squeeze into it. In fact, he had taken only one bath since they moved in. He and Anne both missed soaking in the older, deep bathtubs they enjoyed when they lived back East.

Fortunately, the previous owners, who had built the house, had plumbed the corner of a large exercise room in the basement for a hot tub. They contacted a trusted page 132remodeling contractor, who assured them it would be relatively easy to install a new bathtub and it shouldn’t cost more than $1,500. They decided to go ahead with the project.

First the Nelsons went to the local plumbing retailer to pick out a tub. They soon realized that for a few hundred dollars more they could buy a big tub with water jets (a Jacuzzi). With old age on the horizon a Jacuzzi seemed like a luxury that was worth the extra money.

Originally the plan was to install the tub using the simple plastic frame the bath came with and install a splash guard around the tub. Once Anne saw the tub, frame, and splashguard in the room she balked. She did not like how it looked with the cedar paneling in the exercise room. After significant debate, Anne won out, and the Nelsons agreed to pay extra to have a cedar frame built for the tub and use attractive tile instead of the plastic splashguard. Lukas rationalized that the changes would pay for themselves when they tried to sell the house.

The next hiccup occurred when it came time to address the flooring issue. The exercise room was carpeted, which wasn’t ideal when getting out of a bathtub. The original idea was to install relatively cheap laminated flooring in the drying and undressing area adjacent to the tub. However, the Nelsons couldn’t agree on the pattern to use. One of Anne’s friends said it would be a shame to put such cheap flooring in such a nice room. She felt they should consider using tile. The contractor agreed and said he knew a tile installer who needed work and would give them a good deal.

Lukas reluctantly agreed that the laminated options just didn’t fit the style or quality of the exercise room. Unlike the laminated floor debate, both Anne and Lukas immediately liked a tile pattern that matched the tile used around the tub. Anxious not to delay the project, they agreed to pay for the tile flooring.

Once the tub was installed and the framing was almost completed, Anne realized that something had to be done about the lighting. One of her favorite things to do was to read while soaking in the tub. The existing lights didn’t provide sufficient illumination for doing so. Lukas knew this was “nonnegotiable” and they hired an electrician to install additional lighting over the bathtub.

While the lighting was being installed and the tile was being laid, another issue came up. The original plan was to tile only the exercise room and use remnant rugs to cover the area away from the tub where the Nelsons did their exercises. The Nelsons were very happy with how the tile looked and fit with the overall room. However, it clashed with the laminated flooring in the adjacent bathroom. Lukas agreed with Anne that it really made the adjacent bathroom look cheap and ugly. He also felt the bathroom was so small it wouldn’t cost much more.

After a week the work was completed. Both Lukas and Anne were quite pleased with how everything turned out. It cost much more than they had planned, but they planned to live in the house until the girls graduated from college, so they felt it was a good long-term investment.

Anne had the first turn using the bathtub, followed by their three girls. Everyone enjoyed the Jacuzzi. It was 10:00 p.m. when Lukas began running water for his first bath. At first the water was steaming hot, but by the time he was about to get in, it was lukewarm at best. Lukas groaned, “After paying all of that money I still can’t enjoy a bath.”

The Nelsons rationed bathing for a couple weeks, until they decided to find out what, if anything, could be done about the hot water problem. They asked a reputable heating contractor to assess the situation. The contractor reported that the hot water tank was insufficient to service a family of five. This had not been discovered before page 133because baths were rarely taken in the past. The contractor said it would cost $2,200 to replace the existing water heater with a larger one that would meet their needs. The heating contractor also said if they wanted to do it right they should replace the existing furnace with a more energy-efficient one. A new furnace would not only heat the house but also indirectly heat the water tank. Such a furnace would cost $7,500, but with the improved efficiency and savings in the gas bill, the furnace would pay for itself in 10 years. Besides, the Nelsons would likely receive tax credits for the more fuel-efficient furnace.

Three weeks later, after the new furnace was installed, Lukas settled into the new bathtub. He looked around the room at all the changes that had been made and muttered to himself, “And to think that all I wanted was to soak in a nice, hot bath.”

What factors and forces contributed to scope creep in this case?

Is this an example of good or bad scope creep? Explain.

How could scope creep have been better managed by the Nelsons?

Design elements: Snapshot from Practice, Highlight box, Case icon: ©Sky Designs/Shutterstock

1The limitations of the waterfall method for software development have led to the emergence of Agile project management methods that are the subject of Chapter 15.

2 For a more elaborate scheme for assessing stakeholders, see: Bourne, L. Stakeholder Relationship Management (Farnham, UK: Gower, 2009).