page 318

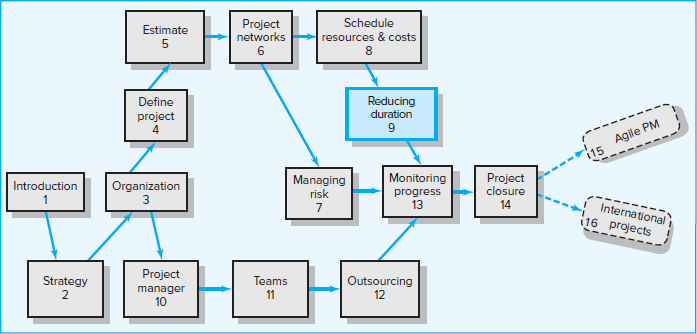

CHAPTER

NINE

9

Reducing Project Duration

page 319

In skating over thin ice our safety is in our speed.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Imagine the following scenarios:

—After finalizing your project schedule, you realize the estimated completion date is two months beyond what your boss publicly promised an important customer.

—Five months into the project, you realize that you are already three weeks behind the drop-dead date for the project.

—Four months into a project, top management changes its priorities and now tells you that money is not an issue. Complete the project ASAP!

What do you do?

This chapter addresses strategies for reducing project duration either prior to setting the baseline for the project or in the midst of project execution. Choice of options is based on the constraints surrounding the project. Here the project priority matrix introduced in Chapter 4 comes into play. For example, there are many more options available for reducing project time if you are not resource constrained than if you page 320cannot spend more than your original budget. We will begin by examining the reasons for reducing project duration, followed by a discussion of different options for accelerating project completion. The chapter will conclude with the classic time-cost framework for selecting which activities to “crash.” Crash is a term that has emerged in the project management lexicon for shortening the duration of an activity or a project beyond when it can be normally done.

9.1 Rationale for Reducing Project Duration

There are many good reasons for attempting to reduce the duration of a project. One of the more important reasons today is time-to-market. Intense global competition and rapid technological advances have made speed a competitive advantage. To succeed, companies have to spot new opportunities, launch project teams, and bring new products or services to the marketplace in a flash. Perhaps in no other industry does speed matter as much as in high-tech industries. For example, a rule of thumb for moderate- to high-technology firms is that a six-month delay in bringing a product to market can result in a loss of market share of about 35 percent. In these cases, high-technology firms typically assume that the time savings and avoidance of lost profits are worth any additional costs to reduce time without any formal analysis. See Snapshot from Practice 9.1: Smartphone Wars for more on this.

page 321

Business survival depends not only on rapid innovation but also on adaptability. Global recession and energy crises have stunned the business world, and the companies that survive will be those that can quickly adapt to new challenges. This requires speedy project management! For example, the fate of the U.S. auto industry depends in part on how quickly they shift their efforts to develop fuel-efficient, alternative forms of transportation.

Another common reason for reducing project time occurs when unforeseen delays—for example, adverse weather, design flaws, and equipment breakdown—cause substantial delays midway in the project. Getting back on schedule usually requires compressing the time on some of the remaining critical activities. The additional costs of getting back on schedule need to be compared with the consequences of being late. This is especially true when time is a top priority.

Incentive contracts can make the reduction of project time rewarding—usually for both the project contractor and the owner. For example, a contractor finished a bridge across a lake 18 months early and received more than $6 million for the early completion. The availability of the bridge to the surrounding community 18 months early to reduce traffic gridlock made the incentive cost to the community seem small to users. In another example, in a continuous improvement arrangement, the joint effort of the owner and contractor resulted in early completion of a river lock and a 50/50 split of the savings to the owner and contractor. See Snapshot from Practice 9.2: Responding to the Northridge Earthquake for a classic example of a contractor who went to great lengths to quickly complete a project with a big payoff.

“Imposed deadlines” is another reason for accelerating project completion. For example, a politician makes a public statement that a new law building will be available in two years. Or the president of a software company remarks in a speech that new advanced software will be available January 22nd. Such statements too often become project objectives without any consideration of the problems or cost of meeting such a date. The project duration time is set while the project is in its “concept” phase before or without any detailed scheduling of all the activities in the project. This phenomenon occurs frequently in practice! Unfortunately, this practice almost always leads to a higher-cost project than one that is planned using low-cost and detailed planning. In addition, quality is sometimes compromised to meet deadlines.

Sometimes very high overhead costs are recognized before the project begins. For example, it may cost $80,000 per day to simply house and feed a construction crew in the farthest reaches of northern Alaska. In these cases it is prudent to examine the direct costs of shortening the critical path versus the overhead cost savings. Usually there are opportunities to shorten a few critical activities at less than the daily overhead rate.

Finally, there are times when it is important to reassign key equipment and/or people to new projects. Under these circumstances, the cost of compressing the project can be compared with the opportunity costs of not releasing key equipment or people.

9.2 Options for Accelerating Project Completion

Managers have several effective methods for crashing specific project activities when resources are not constrained. Several of these are summarized in this section.

page 322

Options When Resources Are Not Constrained

Adding Resources

The most common method for shortening project time is to assign additional staff and equipment to activities. There are limits, however, as to how much speed can be gained by adding staff. Doubling the size of the workforce will not necessarily reduce completion time by half. The relationship is correct only when tasks can be partitioned so minimal communication is needed between workers, as in harvesting a crop by hand or repaving a highway. Most projects are not set up that way; additional workers increase page 323the communication requirements to coordinate their efforts. For example, doubling a team by adding two workers requires six times as much pairwise intercommunication than is required in the original two-person team. Not only is more time needed to coordinate and manage a larger team but also there is the additional delay of training the new people and getting them up to speed on the project. The end result is captured in Brooks’s law: adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.1

Frederick Brooks formulated this principle based on his experience as a project manager for IBM’s System/360 software project during the early 1960s. Although subsequent research confirmed Brooks’s prediction, it also discovered that adding more people to a late project does not always cause the project to be later.2 The key is whether the new staff is added early so there is sufficient time to make up for lost ground once the new members have been fully assimilated.

Outsourcing Project Work

A common method for shortening project time is to subcontract an activity. The subcontractor may have access to superior technology or expertise that will accelerate the completion of the activity. For example, contracting for a backhoe can accomplish in two hours what it can take a team of laborers two days to do. Likewise, by hiring a consulting firm that specializes in Active Directory Service Interfaces (ADSI) programming, a firm may be able to cut in half the time it would take for less experienced, internal programmers to do the work. Subcontracting also frees up resources that can be assigned to a critical activity and will ideally result in a shorter project duration. See Snapshot from Practice 9.3: Outsourcing in Bio-Tech Picks Up Speed. Outsourcing will be addressed more fully in Chapter 12.

page 324

Scheduling Overtime

The easiest way to add more labor to a project is not to add more people but to schedule overtime. If a team works 50 hours a week instead of 40, it might accomplish 20 percent more. By scheduling overtime you avoid the additional costs of coordination and communication encountered when new people are added. If people involved are salaried workers, there may be no additional cost for the extra work. Another advantage is that there are fewer distractions when people work outside normal hours.

Overtime has disadvantages. First, hourly workers are typically paid time and a half for overtime and double time for weekends and holidays. Sustained overtime work by salaried employees may incur intangible costs such as divorce, burnout, and turnover. Turnover is a key organizational concern when there is a shortage of workers. Furthermore, it is an oversimplification to assume that over an extended period of time a person is as productive during her eleventh hour at work as during her third hour of work. There are natural limits to what is humanly possible, and extended overtime may actually lead to an overall decline in productivity when fatigue sets in (DeMarco, 2002).

Working overtime and longer hours is the preferred choice for accelerating project completion, especially when the project team is salaried. The key is to use overtime judiciously. Remember, a project is a marathon, not a sprint! You do not want to run out of energy before the finish line.

Establish a Core Project Team

As discussed in Chapter 3, one of the advantages of creating a dedicated core team to complete a project is speed. Assigning professionals full time to a project avoids the hidden cost of multitasking in which people are forced to juggle the demands of multiple projects. Professionals are allowed to devote their undivided attention to a specific project. This singular focus creates a shared goal that can bind a diverse set of professionals into a highly cohesive team capable of accelerating project completion. Factors that contribute to the emergence of high-performing project teams will be discussed in detail in Chapter 11.

Do It Twice—Fast and Correctly

If you are in a hurry, try building a “quick and dirty” short-term solution; then go back and do it the right way. For example, pontoon bridges are used as temporary solutions to damaged bridges in combat. In business, software companies are notorious for releasing version 1.0 of products that are not completely finished and tested. Subsequent versions 1.1 . . . x correct bugs and add intended functionality to the product. The additional costs of doing it twice are often more than compensated for by the benefits of satisfying the deadline.

Options When Resources Are Constrained

A project manager has fewer options for accelerating project completion when additional resources are not available or the budget is severely constrained. This is especially true once the schedule has been established. This section discusses some of these options, which are also available when resources are not constrained.

Improve the Efficiency of the Project Team

The project team may be able to improve productivity by implementing more efficient ways to do their work. This can be achieved by improving the planning and page 325organization of the project or eliminating barriers to productivity such as excessive bureaucratic interference and red tape.

Fast Tracking

Sometimes it is possible to rearrange the logic of the project network so that critical activities are done in parallel (concurrently) rather than sequentially. This alternative is commonly referred to as fast tracking and is a good one if the project situation is right. When this alternative is given serious attention, it is amazing to observe how creative project team members can be in finding ways to restructure sequential activities in parallel. As noted in Chapter 6, one of the most common methods for restructuring activities is to change a finish-to-start relationship to a start-to-start relationship. For example, instead of waiting for the final design to be approved, manufacturing engineers can begin building the production line as soon as key specifications have been established. Changing activities from sequential to parallel is not without risk, however. Late design changes can produce wasted effort and rework. Fast tracking requires close coordination among those responsible for the activities affected and confidence in the work that has been completed.

Use Critical-Chain Management

Critical-Chain Project Management (CCPM) is designed to accelerate project completion. As discussed in Appendix 8.1, it would be difficult to apply CCPM midstream in a project. CCPM requires considerable training and a shift in habits and perspectives that takes time to adopt. Although there have been reports of immediate gains, especially in terms of completion times, a long-term management commitment is probably necessary to reap full benefits. See Snapshot from Practice 9.4: The Fastest House in the World for an extreme example of CCPM application.

Reduce Project Scope

Probably the most common response to meeting unattainable deadlines is to reduce the scope of the project. This invariably leads to a reduction in the functionality of the project. For example, a new car will average only 25 mpg instead of 30, or a software product will have fewer features than originally planned. While scaling back the scope of the project can lead to big savings in both time and money, it may come at a cost of reducing the value of the project. If the car gets lower gas mileage, will it stand up to competitive models? Will customers still want the software minus the features?

The key to reducing project scope without reducing value is to reassess the true specifications of the project. Often requirements are added under best-case, blue-sky scenarios and represent desirables, but not essentials. Here it is important to talk to the customer and/or project sponsors and explain the situation—“you can get it your way but not until February.” This may force them to accept an extension or to add money to expedite the project. If not, then a healthy discussion of what the essential requirements are and what items can be compromised in order to meet the deadline needs to take place. More intense reexamination of requirements may actually improve the value of the project by getting it done more quickly and for a lower cost.

Compromise Quality

Reducing quality is always an option, but it is rarely acceptable or used. Sacrificing quality may reduce the time of an activity on the critical path.

page 326

In practice the methods most commonly used to crash projects are scheduling overtime, outsourcing, and adding resources. Each of these maintains the essence of the original plan. Options that depart from the original project plan include do it twice and fast tracking. Rethinking of project scope, customer needs, and timing become major considerations for these techniques.

page 327

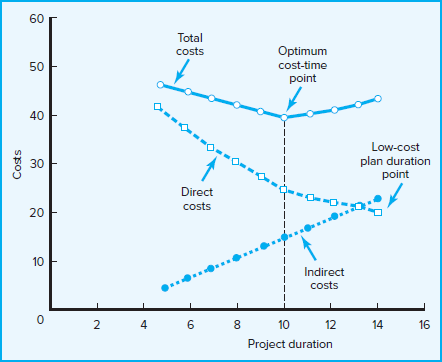

9.3 Project Cost-Duration Graph

Nothing on the horizon suggests that the need to shorten project time will change. In fact, if anything, the pressure to get projects done quicker and sooner is likely to increase in importance. The challenge for the project manager is to use a quick, logical method to compare the benefits of reducing project time with the costs involved. Without sound, logical methods, it is difficult to isolate those activities that will have the greatest impact on reducing project time at least cost. This section describes a procedure for identifying the costs of reducing project time so that comparisons can be made with the benefits of getting the project completed sooner. The method requires gathering direct and indirect costs for specific project durations. Critical activities are searched to find the lowest direct-cost activities that will shorten the project duration. Total costs for specific project durations are computed and then compared with the benefits of reducing project time—before the project begins or while it is in progress.

Explanation of Project Costs

The general nature of project costs is illustrated in Figure 9.1, which shows a project cost-duration graph. The total cost for each duration is the sum of the indirect and direct costs. Indirect costs continue for the life of the project. Hence, any reduction in project duration means a reduction in indirect costs. Direct costs on the graph grow at an increasing rate as the project duration is reduced from its originally planned duration. With the information from a graph such as this for a project, managers can quickly judge any alternative such as meeting a time-to-market deadline. Further discussion of indirect and direct costs is necessary before demonstrating a procedure for developing the information for a graph similar to the one in Figure 9.1.

FIGURE 9.1

Project Cost-Duration Graph

Project Indirect Costs

Indirect costs generally represent overhead costs such as supervision, administration, consultants, and interest. Indirect costs cannot be associated with any particular page 328work package or activity, hence the term. Indirect costs vary directly with time. That is, any reduction in time should result in a reduction of indirect costs. For example, if the daily costs of supervision, administration, and consultants are $2,000, any reduction in project duration would represent a savings of $2,000 per day. If indirect costs are a significant percentage of total project costs, reductions in project time can represent very real savings (assuming the indirect resources can be utilized elsewhere).

Project Direct Costs

Direct costs commonly represent labor, materials, equipment, and sometimes subcontractors. Direct costs are assigned directly to a work package and activity, hence the term. The ideal assumption is that direct costs for an activity time represent normal costs, which typically mean low-cost, efficient methods for a normal time. When project durations are imposed, direct costs may no longer represent low-cost, efficient methods. Costs for the imposed duration date will be higher than for a project duration developed from ideal normal times for activities. Because direct costs are assumed to be developed from normal methods and time, any reduction in activity time should add to the costs of the activity. The sum of the costs of all the work packages or activities represents the total direct costs for the project.

The major challenge faced in creating the information for a graph similar to Figure 9.1 is computing the direct cost of shortening individual critical activities and then finding the total direct cost for each project duration as project time is compressed; the process requires selecting those critical activities that cost the least to shorten. (Note: The graph implies that there is always an optimum cost-time point. This is only true if shortening a schedule has incremental indirect cost savings exceeding the incremental direct cost incurred. However, in practice there are almost always several activities in which the direct costs of shortening are less than the indirect costs.)

9.4 Constructing a Project Cost-Duration Graph

Three major steps are required to construct a project cost-duration graph:

Find total direct costs for selected project durations.

Find total indirect costs for selected project durations.

Sum direct and indirect costs for these selected durations.

The graph is then used to compare additional cost alternatives for benefits. Details of these steps are presented here.

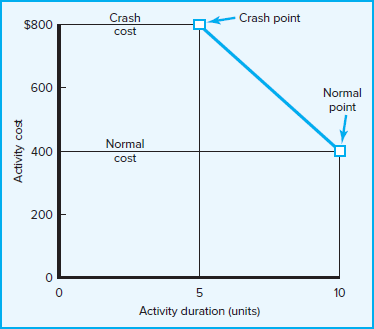

Determining the Activities to Shorten

The most difficult task in constructing a cost-duration graph is finding the total direct costs for specific project durations over a relevant range. The central task is to decide which activities to shorten and how far to carry the shortening process. Basically managers need to look for critical activities that can be shortened with the smallest increase in cost per unit of time. The rationale for selecting critical activities depends on identifying the activity’s normal and crash times and corresponding costs. Normal time for an activity represents low-cost, realistic, efficient methods for completing the activity under normal conditions. The shortest possible time in which an activity can realistically be completed is called its crash time. The direct cost for completing an activity in its crash time is called crash cost. Both normal and crash times and costs page 329are collected from the personnel most familiar with completing the activity. Figure 9.2 depicts a hypothetical cost-duration graph for an activity.

FIGURE 9.2

Activity Graph

The normal time for the activity in Figure 9.2 is 10 time units, and the corresponding cost is $400. The crash time for the activity is five time units and $800. The intersection of the normal time and cost represents the original low-cost, early-start schedule. The crash point represents the maximum time an activity can be compressed. The heavy line connecting the normal and crash points represents the slope, which assumes that the cost of reducing the time of the activity is constant per unit of time. The assumptions underlying the use of this graph are as follows:

The cost-time relationship is linear.

Normal time assumes low-cost, efficient methods to complete the activity.

Crash time represents a limit—the greatest time reduction possible under realistic conditions.

Slope represents cost per unit of time.

All accelerations must occur within the normal and crash times.

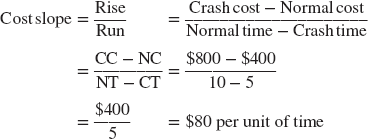

Knowing the slope of activities allows managers to compare which critical activities to shorten. The less steep the cost slope of an activity, the less it costs to shorten one time period; a steeper slope means it will cost more to shorten one time unit. The cost per unit of time or slope for any activity is computed by the following equation:

In Figure 9.2 the rise is the y axis (cost) and the run is the x axis (duration). The slope of the cost line is $80 for each time unit the activity is reduced; the limit reduction of page 330the activity time is five time units. Comparison of the slopes of all critical activities allows us to determine which activity(ies) to shorten to minimize total direct cost. Given the preliminary project schedule (or one in progress) with all activities set to their early-start times, the process of searching critical activities as candidates for reduction can begin. The total direct cost for each specific compressed project duration must be found.

A Simplified Example

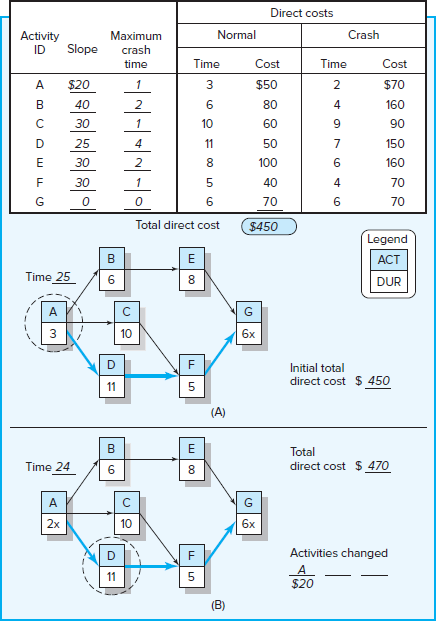

Figure 9.3A presents normal and crash times and costs for each activity, the computed slope and time reduction limit, the total direct cost, and the project network with a duration of 25 time units. Note that the total direct cost for the 25-period duration is $450. This is an anchor point to begin the procedure of shortening the critical path(s) and finding the total direct costs for each specific duration less than 25 time units. The maximum time reduction of an activity is simply the difference between the normal and crash times for an activity. For example, activity D can be reduced from a normal page 331time of 11 time units to a crash time of 7 time units, or a maximum of 4 time units. The positive slope for activity D is computed as follows:

FIGURE 9.3

Cost-Duration Trade-off Example

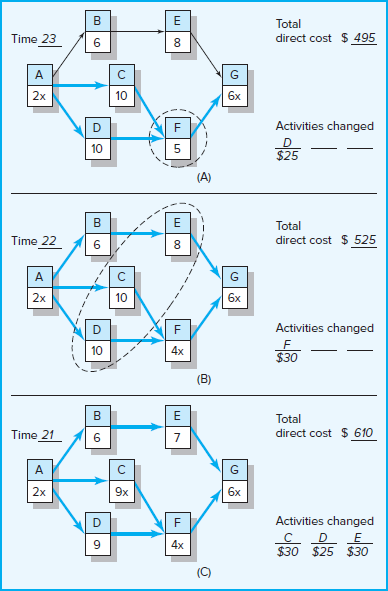

The network shows the critical path to be activities A, D, F, G. Because it is impossible to shorten activity G (“x” is used to indicate this), activity A is circled because it is the least-cost candidate; that is, its slope ($20) is less than the slopes for activities D and F ($25 and $30). Reducing activity A 1 time unit cuts the project duration to 24 time units but increases the total direct costs to $470 ($450 + $20 = $470). Figure 9.3B reflects these changes. The duration of activity A has been reduced to 2 time units; the “x” indicates the activity cannot be reduced any further. Activity D is circled because it costs the least ($25) to shorten the project to 23 time units. Compare the cost of activity F. The total direct cost for a project duration of 23 time units is $495 (see Figure 9.4A).

FIGURE 9.4

Cost-Duration Trade-off Example

page 332

Observe that the project network in Figure 9.4A now has two critical paths—A, C, F, G and A, D, F, G. Reducing the project to 22 time units will require that activity F be reduced; thus, it is circled. This change is reflected in Figure 9.4B. The total direct cost for 22 time units is $525. This reduction has created a third critical path—A, B, E, G; all activities are critical. The least-cost method for reducing the project duration to 21 time units is the combination of the circled activities C, D, E—which cost $30, $25, $30, respectively—and increase total direct costs to $610. The results of these changes are depicted in Figure 9.4C. Although some activities can still be reduced (those without the “x” next to the activity time), no activity or combination of activities will result in a reduction in the project duration.

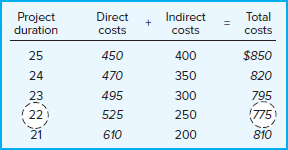

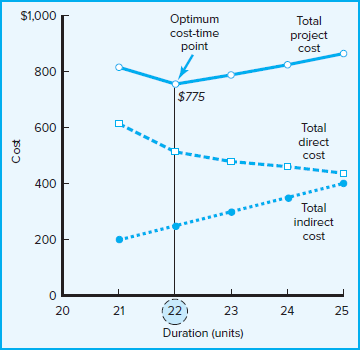

With the total direct costs for the array of specific project durations found, the next step is to collect the indirect costs for the same durations. These costs are typically a rate per day and are easily obtained from the Accounting Department. Figure 9.5 presents the total direct costs, total indirect costs, and total project costs. The same costs are plotted in Figure 9.6. This graph shows that the optimum cost-time duration is 22 time units and $775. Assuming the project will actually materialize as planned, any movement away from this time duration will increase project costs. The movement from 25 to 22 time units occurs because, in this range, the absolute slopes of the indirect costs are greater than the direct-cost slopes.

FIGURE 9.5 Summary Costs by Duration

FIGURE 9.6 Project Cost-Duration Graph

9.5 Practical Considerations

Using the Project Cost-Duration Graph

The project cost-duration graph, as presented in Figures 9.1 and 9.6, is valuable in comparing any proposed alternative or change with the optimum cost and time. More importantly the creation of such a graph keeps the importance of indirect costs in the page 333forefront of decision making. Indirect costs are frequently forgotten in the field when the pressure for action is intense. Finally, such a graph can be used before the project begins or while the project is in progress.

Creating the graph in the pre-project planning phase without an imposed duration is the first choice because normal time is more meaningful. Creating the graph in the project planning phase with an imposed duration is less desirable because normal time is made to fit the imposed date and is probably not low cost. Creating the graph after the project has started is the least desirable because some alternatives may be ruled out of the decision process. Managers may choose not to use the formal procedure demonstrated. However, regardless of the method used, the principles and concepts inherent in the formal procedure are highly applicable in practice and should be considered in any cost-duration trade-off decision.

Crash Times

Collecting crash times for even a moderate-sized project can be difficult. The meaning of crash time is difficult to communicate. What is meant when you define crash time as “the shortest time you can realistically complete an activity”? Crash time is open to different interpretations and judgments. Some estimators feel very uncomfortable providing crash times. Regardless of the comfort level, the accuracy of crash times and costs is frequently rough at best, when compared with normal time and cost.

Linearity Assumption

Because the accuracy of compressed activity times and costs is questionable, the concern of some theorists—that the relationship between cost and time is not linear but curvilinear—is seldom a concern for practicing managers. Reasonable, quick comparisons can be made using the linear assumption.3 The simple approach is adequate for most projects. There are rare situations in which activities cannot be crashed by single time units. Instead, crashing is “all or nothing.” For example, activity A will take 10 days (for, say, $1,000) or it will take 7 days (for, say, $1,500), but no options exist in which activity A will take 8 or 9 days to complete. In a few, rare cases of very large, complex, long-duration projects, present value techniques may be useful; such techniques are beyond the scope of this text.

Choice of Activities to Crash Revisited

The cost-time crashing method relies on choosing the cheapest method for reducing the duration of the project. There are other factors that should be assessed beyond simply cost. First, the inherent risks involved in crashing particular activities need to be considered. Some activities are riskier to crash than others. For example, accelerating the completion of a software design code may not be wise if it increases the likelihood of errors surfacing downstream. Conversely, crashing a more expensive activity may be wise if fewer inherent risks are involved.

Second, the timing of activities needs to be considered. Crashing an early activity may be prudent if there is concern that subsequent activities are likely to be delayed, and absorb the time gained. Then the manager would still have the option of crashing final activities to get back on schedule.

Third, crashing frequently results in overallocation of resources. The resources required to accelerate a cheaper activity may suddenly not be available. Resource availability, not cost, may dictate which activities are crashed.

page 334

Finally, the impact of crashing would have on the morale and motivation of the project team needs to be assessed. If the least-cost method repeatedly signals a subgroup to accelerate progress, fatigue and resentment may set in. Conversely, if overtime pay is involved, other team members may resent not having access to this benefit. This situation can lead to tension within the entire project team. Good project managers gauge the response that crashing activities will have on the entire project team. See Snapshot from Practice 9.5: I’ll Bet You . . . for a novel approach to motivating employees to work faster.

Time Reduction Decisions and Sensitivity

Should the project owner or project manager go for the optimum cost-time? The answer is “It depends.” Risk must be considered. Recall from our example that the page 335optimum project time point represented a reduced project cost and was less than the original normal project time (review Figure 9.6). The project direct-cost line near the normal point is usually relatively flat. Because indirect costs for the project are usually greater in the same range, the optimum cost-time point is less than the normal time point. Logic of the cost-time procedure suggests managers should reduce the project duration to the lowest total cost point and duration.

How far to reduce the project time from the normal time toward the optimum depends on the sensitivity of the project network. A network is sensitive if it has several critical or near-critical paths. In our example, project movement toward the optimum time requires spending money to reduce critical activities, resulting in slack reduction and/or more critical paths and activities. Slack reduction in a project with several near-critical paths increases the risk of being late. The practical outcome can be a higher total project cost if some near-critical activities are delayed and become critical; the money spent reducing activities on the original critical path would be wasted. Sensitive networks require careful analysis. The bottom line is that the compression of projects with several near-critical paths reduces scheduling flexibility and increases the risk of delaying the project. The outcome of such analysis will probably suggest only a partial movement from the normal time toward the optimum time.

There is a positive situation where moving toward the optimum time can result in large savings—this occurs when the network is insensitive. A project network is insensitive if it has a dominant critical path, that is, no near-critical paths. In this project circumstance, movement from the normal time point toward the optimum time will not create new or near-critical activities. The bottom line here is that the reduction of the slack of noncritical activities increases the risk of their becoming critical only slightly when compared with the effect in a sensitive network. Insensitive networks hold the greatest potential for real, sometimes large, savings in total project costs with a minimum risk of noncritical activities becoming critical.

Insensitive networks are not a rarity in practice; they occur in perhaps 25 percent of all projects. For example, a light rail project team observed from their network a dominant critical path and relatively high indirect costs. It soon became clear that by spending some dollars on a few critical activities, very large savings of indirect costs could be realized. Savings of several million dollars were spent extending the rail line and adding another station. The logic found in this example is just as applicable to small projects as to large ones. Insensitive networks with high indirect costs can produce large savings.

Ultimately, deciding if and which activities to crash is a judgment call requiring careful consideration of the options available, the costs and risks involved, and the importance of meeting a deadline.

9.6 What If Cost, Not Time, Is the Issue?

In today’s fast-paced world, there appears to be a greater emphasis on getting things done quickly. Still, organizations are always looking for ways to get things done cheaply. This is especially true for fixed-bid projects, where profit margin is derived from the difference between the bid and the actual cost of the project. Every dollar saved is a dollar in your pocket. Sometimes, in order to secure a contract, bids are tight, which puts added pressure on cost containment. In other cases, there are financial incentives tied to cost containment.

page 336

Even in situations where cost is transferred to customers, there is pressure to reduce cost. Cost overruns make for unhappy customers and can damage future business opportunities. Budgets can be fixed or cut, and when contingency funds are exhausted, cost overruns have to be made up with remaining activities.

As discussed earlier, shortening project duration may come at the expense of working overtime, adding additional personnel, and using more expensive equipment and/or materials. Conversely, sometimes cost savings can be generated by extending the duration of a project. This may allow for a smaller workforce, less-skilled (expensive) labor, and even cheaper equipment and materials to be used. Discussed in this section are some of the more commonly used options for cutting costs.

Reduce Project Scope

Just as scaling back the scope of the project can gain time, delivering less than what was originally planned also produces significant savings. Again, calculating the savings of a reduced project scope begins with the work breakdown structure. However, since time is not the issue, you do not need to focus on critical activities. For example, on over-budget movie projects it is not uncommon to replace location shots with stock footage to cut costs.

Have Owner Take on More Responsibility

One way of reducing project costs is identifying tasks that customers can do themselves. Homeowners frequently use this method to reduce costs on home improvement projects. For example, to reduce the cost of a bathroom remodel, a homeowner may agree to paint the room instead of paying the contractor to do it. On IS projects, a customer may agree to take on some of the responsibility for testing equipment or providing in-house training. Naturally this arrangement is best negotiated before the project begins. Customers are less receptive to this idea if you suddenly spring it on them. An advantage of this method is that, while costs are lowered, the original scope is retained. Clearly this option is limited to areas in which the customer has the expertise and capability to pick up the tasks.

Outsource Project Activities or Even the Entire Project

When estimates exceed budget, it makes sense to not only re-examine the scope but also search for cheaper ways to complete the project. Perhaps instead of relying on internal resources, it would be more cost effective to outsource segments or even the entire project, opening up work to external price competition. Specialized subcontractors often enjoy unique advantages, such as material discounts for large quantities, as well as equipment that gets the work done not only more quickly but also less expensively. They may have lower overhead and labor costs. For example, to reduce costs of software projects, many American firms outsource work to firms overseas where the salary of a software engineer is one-third that of an American software engineer. However, outsourcing means you have less control over the project and will need to have clearly definable deliverables.

Brainstorm Cost Savings Options

Just as project team members can be a rich source of ideas for accelerating project activities, they can offer tangible ways for reducing project costs. For example, one project manager reported that her team was able to come up with over $75,000 worth page 337of cost-saving suggestions without jeopardizing the scope of the project. Project managers should not underestimate the value of simply asking if there is a cheaper, better way.

Summary

The need for reducing the project duration occurs for many reasons such as imposed deadlines, time-to-market considerations, incentive contracts, key resource needs, high overhead costs, or simply unforeseen delays. These situations are very common in practice and are known as cost-time trade-off decisions. This chapter presented a logical, formal process for assessing the implications of situations that involve shortening the project duration. Crashing the project duration increases the risk of being late. How far to reduce the project duration from the normal time toward the optimum depends on the sensitivity of the project network. A sensitive network is one that has several critical or near-critical paths. Great care should be taken when shortening sensitive networks to avoid increasing project risks. Conversely, insensitive networks represent opportunities for potentially large project cost savings by eliminating some overhead costs with little downside risk.

Alternative strategies for reducing project time were discussed within the context of whether or not the project is resource limited. Project acceleration typically comes at a cost of either spending money for more resources or compromising the scope of the project. If the latter is the case, then it is essential that all relevant stakeholders be consulted so that everyone accepts the changes that have to be made. One other key point is the difference in implementing time-reducing activities in the midst of project execution versus incorporating them into the project plan. You typically have far fewer options once the project is under way than before it begins. This is especially true if you want to take advantage of the new scheduling methodologies such as fast tracking and critical chain. Time spent up front considering alternatives and developing contingency plans will lead to time savings in the end.

Key Terms

Review Questions

What are five common reasons for crashing a project?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of reducing project scope to accelerate a project? What can be done to reduce the disadvantages?

Why is scheduling overtime a popular choice for getting projects back on schedule? What are the potential problems of relying on this option?

Identify four indirect costs you might find on a moderately complex project. Why are these costs classified as indirect?

How can a cost-duration graph be used by the project manager? Explain.

Reducing the project duration increases the risk of being late. Explain.

It is possible to shorten the critical path and save money. Explain how.

page 338

SNAPSHOT  FROM PRACTICE

FROM PRACTICE

Discussion Questions

9.1 Smartphone Wars

Can you think of another product like smartphones that have rapid new-product releases?

What do you think would have happened if for some reason it took Samsung three years to release its next-generation smartphone?

9.2 Responding to the Northridge Earthquake

What options for accelerating project completion did C. C. Myers use on the Northridge Earthquake project?

If you were Governor Pete Wilson, how would you respond to criticism that C. C. Meyers made too much profit from the project?

9.3 Outsourcing in Bio-Tech Picks Up Speed

What benefits do small pharma firms accrue through outsourcing project work?

What do you think Dan Gold is referring to when he argues that all parties must make a concerted effort to work as partners?

9.4 The Fastest House in the World.

Watch the YouTube video “World Record: Fastest House Built.”

www.youtube.com/watch?v=AwEcW6hH-B8

What options did Habitat for Humanity(H4H) use to complete the house so quickly?

How did H4H reduce the chances of human error on the project?

9.5 I’ll Bet You . . .

Have you ever used bets to motivate someone? How effective was it?

Have you ever responded to a bet? How effective was it?

Exercises

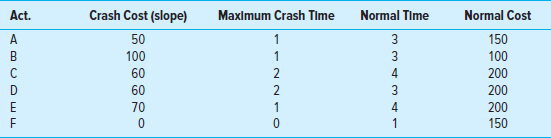

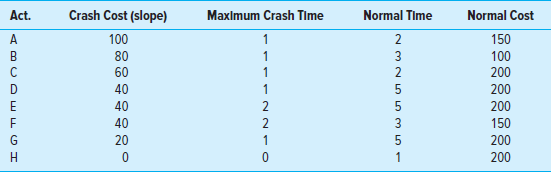

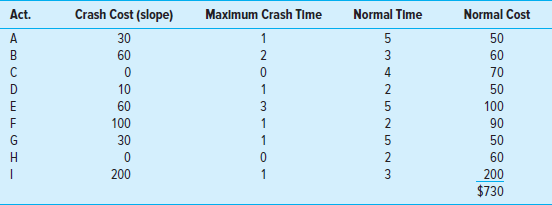

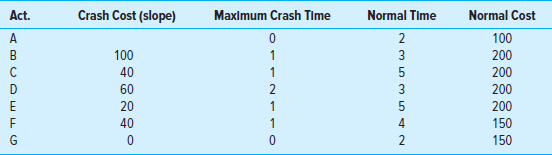

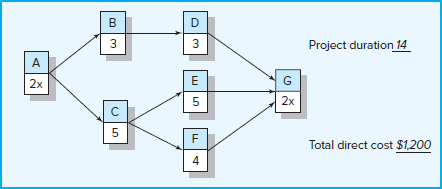

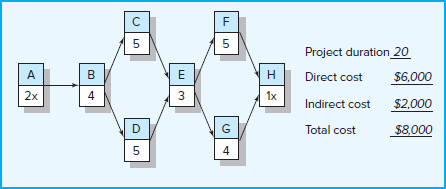

Use the following information to compress one time unit per move using the least-cost method. Reduce the schedule until you reach the crash point of the network. For each move identify what activity or activities were crashed and the adjusted total cost.

Note: The correct normal project duration, critical path, and total direct cost are provided.

page 339

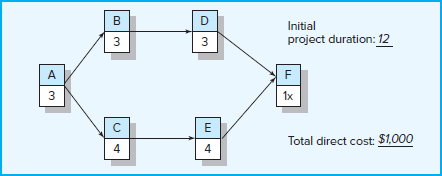

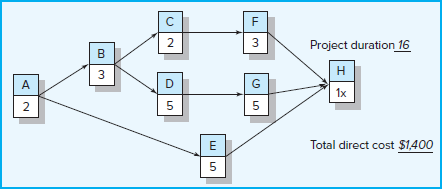

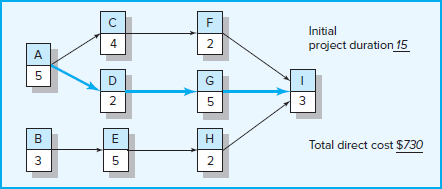

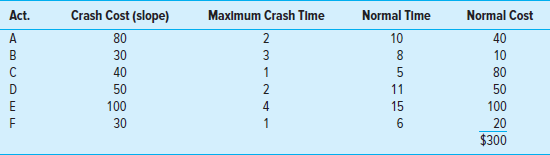

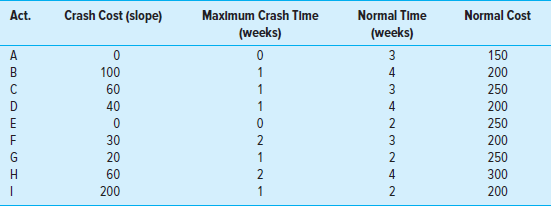

Use the following information contained below to compress one time unit per move using the least-cost method.* Reduce the schedule until you reach the crash point of the network. For each move identify what activity or activities were crashed and the adjusted total cost.

Note: Choose B instead of C and E (equal costs) because it is usually smarter to crash early rather than late AND one activity instead of two activities

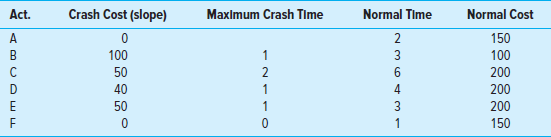

Use the following information to compress one time unit per move using the least-cost method. Reduce the schedule until you reach the crash point of the network. For each move identify what activity or activities were crashed and the adjusted total cost.

page 340

Given the data and information that follow, compute the total direct cost for each project duration. If the indirect costs for each project duration are $90 (15 time units), $70 (14), $50 (13), $40 (12), and $30 (11), compute the total project cost for each duration. What is the optimum cost-time schedule for the project? What is this cost?

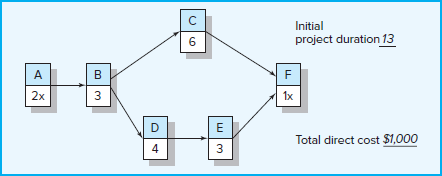

page 341 Use the following information to compress one time unit per move using the least-cost method. Assume the total indirect cost for the project is $700 and there is a savings of $50 per time unit reduced. Record the total direct, indirect, and project costs for each duration. What is the optimum cost-time schedule for the project? What is the cost?

Note: The correct normal project duration and total direct cost are provided.

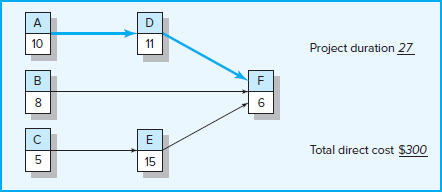

If the indirect costs for each duration are $300 for 27 days, $240 for 26 days, $180 for 25 days, $120 for 24 days, $60 for 23 days, and $50 for 22 days, compute the direct, indirect, and total costs for each duration. What is the optimum cost-time schedule? The customer offers you $10 for every day you shorten the project from your original network. Would you take it? If so for how many days?

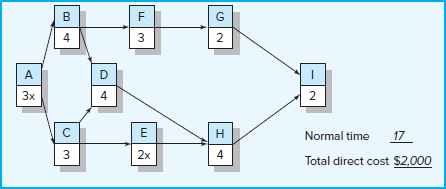

page 342 Use the following information to compress one time unit per move using the least-cost method. Assume the total indirect cost for the project is $2,000 and there is a savings of $100 per time unit reduced. Calculate the total direct, indirect, and project costs for each duration. Plot these costs on a graph. What is the optimum cost-time schedule for the project?

Note: The correct normal project duration and total direct cost are provided.

Use the following information to compress one time unit per move using the least-cost method.* Reduce the schedule until you reach the crash point of the network. For each move identify what activity or activities were crashed and the adjusted total cost, and explain your choice if you have to choose between activities that cost the same.

If the indirect cost for each duration is $1,500 for 17 weeks, $1,450 for 16 weeks, $1,400 for 15 weeks, $1,350 for 14 weeks, $1,300 for 13 weeks, $1,250 for 12 weeks, $1,200 for 11 weeks, and $1,150 for 10 weeks, what is the optimum cost-time schedule for the project? What is the cost?

page 343

*The solution to this exercise can be found in Appendix One.

*The solution to this exercise can be found in Appendix One.

References

Abdel-Hamid, T., and S. Madnick, Software Project Dynamics: An Integrated Approach (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1991).

Baker, B. M., “Cost/Time Trade-off Analysis for the Critical Path Method,” Journal of the Operational Research Society, vol. 48, no. 12 (1997), pp. 1241–44.

Brooks, F. P., Jr., The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering Anniversary Edition (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Longman, Inc., 1994), pp. 15–26.

DeMarco, T., Slack: Getting Past Burnout, Busywork, and the Myth of Total Efficiency (New York: Broadway, 2002).

Gordon, R. I., and J. C. Lamb, “A Closer Look at Brooks’s Law,” Datamation, June 1977, pp. 81–86.

Ibbs, C. W., S. A. Lee, and M. I. Li, “Fast-Tracking’s Impact on Project Change,” Project Management Journal, vol. 29, no. 4 (1998), pp. 35–42.

Khang, D. B., and M. Yin, “Time, Cost, and Quality Trade-off in Project Management,” International Journal of Project Management, vol. 17, no. 4 (1999), pp. 249–56.

Perrow, L. A., Finding Time: How Corporations, Individuals, and Families Can Benefit from New Work Practices (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997).

Roemer, T. R., R. Ahmadi, and R. Wang, “Time-Cost Trade-offs in Overlapped Product Development,” Operations Research, vol. 48, no. 6 (2000), pp. 858–65.

Smith, P. G., and D. G. Reinersten, Developing Products in Half the Time, 2nd ed. (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1997).

Verzuh, E., The Fast Forward MBA in Project Management, 4th ed. (New York: John Wiley, 2015).

Vroom, V. H., Work and Motivation (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1964).

page 344

Case 9.1

International Capital, Inc.—Part B

Given the project network derived in Part A of the case from Chapter 7, Appendix 7.1, Beth also wants to be prepared to answer any questions concerning compressing the project duration. This question will almost always be entertained by the Accounting Department, the review committee, and the client. To be ready for the compression question, Beth has prepared the following data in case it is necessary to crash the project. (Use your weighted average times [te] computed in Part A of the International Capital case found in Chapter 7.)

| Activity | Normal Cost | Maximum Crash Time | Crash Cost/Day |

| A | $ 3,000 | 3 | $ 500 |

| B | 5,000 | 2 | 1,000 |

| C | 6,000 | 0 | — |

| D | 20,000 | 3 | 3,000 |

| E | 10,000 | 2 | 1,000 |

| F | 7,000 | 1 | 1,000 |

| G | 20,000 | 2 | 3,000 |

| H | 8,000 | 1 | 2,000 |

| I | 5,000 | 1 | 2,000 |

| J | 7,000 | 1 | 1,000 |

| K | 12,000 | 6 | 1,000 |

| Total normal costs = | $103,000 |

Using the data provided, determine the activity crashing decisions and best-time cost project duration. Given the information you have developed, what suggestions would you give Beth to ensure she is well prepared for the project review committee? Assume the overhead costs for this project are $700 per workday. Will this alter your suggestions?

Case 9.2

Ventura Baseball Stadium—Part B

This case is based on a project introduced in Chapter 6 (p. 209). You will need to use the project plan created in the Ventura Baseball Stadium case to complete this assignment.

Ventura Baseball Stadium is a 47,000-seat professional baseball stadium. G&E Company began construction on June 10, 2019, and will complete it on February 21, 2022. The stadium must be ready for the opening of the 2022 regular season. G&E would accrue a $500,000-per-day penalty for not meeting the April 3, 2022, deadline.

The project started on time and was progressing well until an accident occurred during the pouring of the lower bowl. Two workers were seriously injured, and the activity was delayed four weeks while the cause of the accident was investigated and the site cleared to proceed.

The president of G&E Company, Percival Young, is concerned about the delay of the project. The project began with roughly six weeks of cushion between expected page 345completion deadline and imposed deadline of April 3 (opening day). Now there is only a two-week cushion with over a year’s worth of work still to be completed. He has asked you to consider the following options to reduce the duration of the project and restore some of the time buffer that has been lost.

Assign overtime to complete the installation of seats in 120 days, not 140 days.

Assign overtime to complete the infrastructure in 100 days, not 120 days.

Introduce a start-to-start lag whereby construction of the roof begins 70 days after the start of building roof supports.

Introduce a start-to-start lag whereby installing the scoreboard can start 100 days after the start of construction of the upper steel bowl.

Introduce a start-to-start lag whereby installing seats can start 100 days after the start of both pouring the main concourse and constructing the upper steel bowl.

Write a short memo to Young, detailing your recommendation and rationale.

Case 9.3

Whitbread World Sailboat Race

Each year countries enter their sailing vessels in the nine-month Round the World Whitbread Sailboat Race. In recent years about 14 countries entered sailboats in the race. Each year’s sailboat entries represent the latest technologies and human skills each country can muster.

Bjorn Ericksen has been selected as a project manager because of his past experience as a master helmsman and because of his recent fame as the “best designer of racing sailboats in the world.” Bjorn is pleased and proud to have the opportunity to design, build, test, and train the crew for next year’s Whitbread entry for his country. Bjorn has picked Karin Knutsen (as chief design engineer) and Trygve Wallvik (as master helmsman) to be team leaders responsible for getting next year’s entry ready for the traditional parade of all entries on the Thames River in the United Kingdom, which signals the start of the race.

As Bjorn begins to think of a project plan, he sees two parallel paths running through the project—design and construction and crew training. Last year’s boat will be used for training until the new entry can have the crew on board to learn maintenance tasks. Bjorn calls Karin and Trygve together to develop a project plan. All three agree the major goal is to have a winning boat and crew ready to compete in next year’s competition at a cost of $3.2 million. A check of Bjorn’s calendar indicates he has 45 weeks before next year’s vessel must leave port for the United Kingdom to start the race.

THE KICKOFF MEETING

Bjorn asks Karin to begin by describing the major activities and the sequence required to design, construct, and test the boat. Karin starts by noting that design of the hull, deck, mast, and accessories should only take 6 weeks—given the design prints from past race entries and a few prints from other countries’ entries. After the design is complete, the hull can be constructed, mast ordered, sails ordered, and accessories ordered. The hull will require 12 weeks to complete. The mast can be ordered and will require a lead time of 8 weeks; the seven sails can be ordered and will take 6 weeks to get; accessories can be ordered and will take 15 weeks to receive. As soon as the page 346hull is finished, the ballast tanks can be installed, requiring 2 weeks. Then the deck can be built, which will require 5 weeks. Concurrently the hull can be treated with special sealant and friction-resistance coating, taking 3 weeks. When the deck is completed and mast and accessories received, the mast and sails can be installed, requiring 2 weeks; the accessories can be installed, which will take 6 weeks. When all of these activities have been completed, the ship can be sea-tested, which should take 5 weeks. Karin believes she can have firm cost estimates for the boat in about 2 weeks.

Trygve believes he can start selecting the 12-man or -woman crew and securing their housing immediately. He believes it will take 6 weeks to get a committed crew on-site and 3 weeks to secure housing for the crew members. Trygve reminds Bjorn that last year’s vessel must be ready to use for training the moment the crew is on-site until the new vessel is ready for testing. Keeping the old vessel operating will cost $4,000 per week as long as it is used. Once the crew is on-site and housed, they can develop and implement a routine sailing and maintenance training program, which will take 15 weeks (using the old vessel). Also, once the crew is selected and on-site, crew equipment can be selected, taking only 2 weeks. Then crew equipment can be ordered; it will take 5 weeks to arrive. When the crew equipment and maintenance training program are complete, crew maintenance on the new vessel can begin; this should take 10 weeks. But crew maintenance on the new vessel cannot begin until the deck is complete and the mast, sails, and accessories have arrived. Once crew maintenance on the new vessel begins, the new vessel will cost $6,000 per week until sea training is complete. After the new ship maintenance is complete and while the boat is being tested, initial sailing training can be implemented; training should take 7 weeks. Finally, after the boat is tested and initial training is complete, regular sea training can be implemented—weather permitting; regular sea training requires 8 weeks. Trygve believes he can put the cost estimates together in a week, given last year’s expenses.

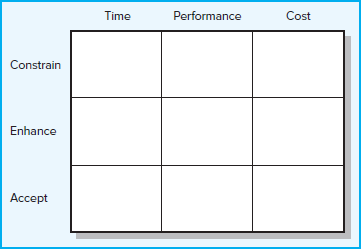

Bjorn is pleased with the expertise displayed by his team leaders. But he believes they need to have someone develop one of those critical path networks to see if they can safely meet the start deadline for the race. Karin and Trygve agree. Karin suggests the cost estimates should also include crash costs for any activities that can be compressed and the resultant costs for crashing. Karin also suggests the team complete the priority matrix shown in Figure C9.1 for project decision making.

FIGURE C9.1

Project Priority Matrix: Whitbread Project

page 347

TWO WEEKS LATER

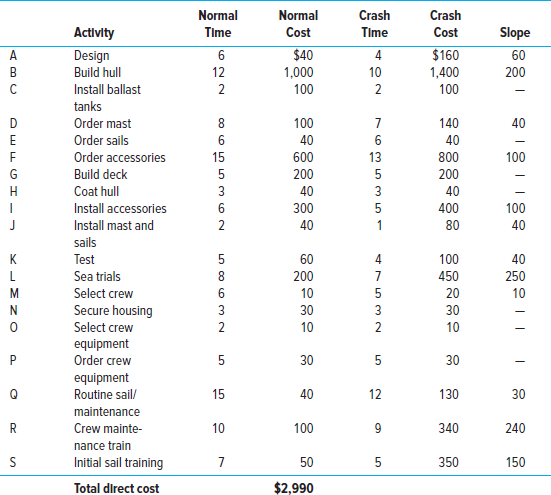

Karin and Trygve submit the following cost estimates for each activity and corresponding crash costs to Bjorn (costs are in thousands of dollars):

Bjorn reviews the materials and wonders if the project will come in within the budget of $3.2 million and in 45 weeks. Advise the Whitbread team of their situation.

Case 9.4

Nightingale Project—Part A

You are the assistant project manager to Rassy Brown, who is in charge of the Nightingale project. Nightingale was the code name given to the development of a handheld electronic medical reference guide. Nightingale would be designed for emergency medical technicians and paramedics who need a quick reference guide to use in emergency situations.

page 348

Rassy and her project team were developing a project plan aimed at producing 30 working models in time for MedCON, the biggest medical equipment trade show each year. Meeting the MedCON October 25 deadline was critical to success. All the major medical equipment manufacturers demonstrated and took orders for new products at MedCON. Rassy had also heard rumors that competitors were considering developing a similar product, and she knew that being first to market would have a significant sales advantage. Besides, top management made funding contingent upon developing a workable plan for meeting the MedCON deadline.

The project team spent the morning working on the schedule for Nightingale. They started with the WBS and developed the information for a network, adding activities when needed. Then the team added the time estimates they had collected for each activity. Following is the preliminary information for activities with duration time and predecessors.

| Activity | Description | Duration | Predecessor |

| 1 | Architectural decisions | 10 | None |

| 2 | Internal specifications | 20 | 1 |

| 3 | External specifications | 18 | 1 |

| 4 | Feature specifications | 15 | 1 |

| 5 | Voice recognition | 15 | 2, 3 |

| 6 | Case | 4 | 2, 3 |

| 7 | Screen | 2 | 2, 3 |

| 8 | Speaker output jacks | 2 | 2, 3 |

| 9 | Tape mechanism | 2 | 2, 3 |

| 10 | Database | 40 | 4 |

| 11 | Microphone/soundcard | 5 | 4 |

| 12 | Pager | 4 | 4 |

| 13 | Barcode reader | 3 | 4 |

| 14 | Alarm clock | 4 | 4 |

| 15 | Computer I/O | 5 | 4 |

| 16 | Review design | 10 | 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 |

| 17 | Price components | 5 | 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 |

| 18 | Integration | 15 | 16, 17 |

| 19 | Document design | 35 | 16 |

| 20 | Procure prototype components | 20 | 18 |

| 21 | Assemble prototypes | 10 | 20 |

| 22 | Lab test prototypes | 20 | 21 |

| 23 | Field test prototypes | 20 | 19, 22 |

| 24 | Adjust design | 20 | 23 |

| 25 | Order stock parts | 15 | 24 |

| 26 | Order custom parts | 2 | 24 |

| 27 | Assemble first production unit | 10 | 25, FS—8 time units |

| 26, FS—13 time units | |||

| 28 | Test unit | 10 | 27 |

| 29 | Produce 30 units | 15 | 28 |

| 30 | Train sales representatives | 10 | 29 |

page 349

Use any project network computer program available to you to develop the schedule for activities (see the case appendix following Case 9.5 for further instructions)—noting late and early times, the critical path, and estimated completion for the project.

Prepare a short memo that addresses the following questions:

Will the project as planned meet the October 25 deadline?

What activities lie on the critical path?

How sensitive is this network?

Case 9.5

Nightingale Project—Part B

Rassy and the team were concerned with the results of your analysis. They spent the afternoon brainstorming alternative ways for shortening the project duration. They rejected outsourcing activities because most of the work was developmental in nature and could only be done in-house. They considered altering the scope of the project by eliminating some of the proposed product features. After much debate, they felt they could not compromise any of the core features and be successful in the marketplace. They then turned their attention to accelerating the completion of activities through overtime and adding additional technical manpower. Rassy had built into her proposal a discretionary fund of $200,000. She was willing to invest up to half of this fund to accelerate the project but wanted to hold on to at least $100,000 to deal with unexpected problems. After a lengthy discussion, her team concluded that the following activities could be reduced at the specified cost:

Development of voice recognition system could be reduced from 15 days to 10 days at a cost of $15,000.

Creation of database could be reduced from 40 days to 35 days at a cost of $35,000.

Document design could be reduced from 35 days to 30 days at a cost of $25,000.

External specifications could be reduced from 18 days to 12 days at a cost of $20,000.

Procure prototype components could be reduced from 20 days to 15 days at a cost of $30,000.

Order stock parts could be reduced from 15 days to 10 days at a cost of $20,000.

Ken Clark, a development engineer, pointed out that the network contained only finish-to-start relationships and that it might be possible to reduce project duration by creating start-to-start lags. For example, he said that his people would not have to wait for all of the field tests to be completed to begin making final adjustments in the design. They could start making adjustments after the first 15 days of testing. page 350The project team spent the remainder of the day analyzing how they could introduce lags into the network to shorten the project. They concluded that the following finish-to-start relationships could be converted into lags:

Document design could begin 5 days after the start of the review design.

Adjust design could begin 15 days after the start of field test prototypes.

Order stock parts could begin 5 days after the start of adjust design.

Order custom parts could begin 5 days after the start of adjust design.

Training sales representatives could begin 5 days after the start of test unit and completed 5 days after the production of 30 units.

As the meeting adjourns, Rassy turns to you and tells you to assess the options presented and try to develop a schedule that will meet the October 25 deadline. You are to prepare a report to be presented to the project team that answers the following questions:

Is it possible to meet the deadline?

If so, how would you recommend changing the original schedule (Part A) and why? Assess the relative impact of crashing activities versus introducing lags to shorten project duration.

What would the new schedule look like?

What other factors should be considered before finalizing the schedule?

CASE APPENDIX: TECHNICAL DETAILS

Create your project schedule and assess your options based on the following information:

The project will begin the first working day in January, 2017.

The following holidays are observed: January 1, Memorial Day (last Monday in May), July 4, Labor Day (first Monday in September), Thanksgiving Day (fourth Thursday in November), December 25 and 26.

If a holiday falls on a Saturday, then Friday will be given as an extra day off; if it falls on a Sunday, then Monday will be given as a day off.

The project team works Monday through Friday, 8-hour days.

If you choose to reduce the duration of any one of the activities mentioned, then it must be for the specified time and cost (e.g., you cannot choose to reduce database to 37 days at a reduced cost; you can only reduce it to 35 days at a cost of $35,000).

You can only spend up to $100,000 to reduce project activities; lags do not contain any additional costs.

page 351

Case 9.6

The “Now” Wedding—Part A*

On December 31 of last year, Lauren burst into the family living room and announced that she and Connor (her college boyfriend) were going to be married. After recovering from the shock, her mother hugged her and asked, “When?” The following conversation resulted:

| Lauren: | January 21. |

| Mom: | What? |

| Dad: | The Now Wedding will be the social hit of the year. Wait a minute. Why so soon? |

| Lauren: | Because on January 30 Connor, who is in the National Guard, will be shipping out overseas. We want a week for a honeymoon. |

| Mom: | But, Honey, we can’t possibly finish all the things that need to be done by then. Remember all the details that were involved in your sister’s wedding? Even if we start tomorrow, it takes a day to reserve the church and reception hall, and they need at least 14 days’ notice. That has to be done before we can start decorating, which takes 3 days. An extra $200 on Sunday would probably cut that 14-day notice to 7 days, though. |

| Dad: | Oh, boy! |

| Lauren: | I want Jane Summers to be my maid of honor. |

| Dad: | But she’s in the Peace Corps in Guatemala, isn’t she? It would take her 10 days to get ready and drive up here. |

| Lauren: | But we could fly her up in 2 days and it would only cost $1,000. |

| Dad: | Oh, boy! |

| Mom: | And catering! It takes 2 days to choose the cake and decorations, and Jack’s Catering wants at least 5 days’ notice. Besides, we’d have to have those things before we could start decorating. |

| Lauren: | Can I wear your wedding dress, Mom? |

| Mom: | Well, we’d have to replace some lace, but you could wear it, yes. We could order the lace from New York when we order the material for the bridesmaids’ dresses. It takes 8 days to order and receive the material. The pattern needs to be chosen first, and that would take 3 days. |

| Dad: | We could get the material here in 5 days if we paid an extra $20 to airfreight it. Oh, boy! |

| Lauren: | I want Mrs. Jacks to work on the dresses. |

| Mom: | But she charges $48 a day. |

| Dad: | Oh, boy! |

| Mom: | If we did all the sewing we could finish the dresses in 11 days. If Mrs. Jacks helped we could cut that down to 6 days at a cost of $48 for each day less than 11 days. She is very good, too. |

| Lauren: | I don’t want anyone but her.page 352 |

| Mom: | It would take another 2 days to do the final fitting and 2 more days to clean and press the dresses. They would have to be ready by rehearsal night. We must have rehearsal the night before the wedding. |

| Dad: | Everything should be ready rehearsal night. |

| Mom: | We’ve forgotten something. The invitations! |

| Dad: | We should order the invitations from Bob’s Printing Shop, and that usually takes 7 days. I’ll bet he would do it in 6 days if we slipped him an extra $20! |

| Mom: | It would take us 2 days to choose the invitation style before we could order them and we want the envelopes printed with our return address. |

| Lauren: | Oh! That will be elegant. |

| Mom: | The invitations should go out at least 10 days before the wedding. If we let them go any later, some of the relatives would get theirs too late to come and that would make them mad. I’ll bet that if we didn’t get them out until 8 days before the wedding, Aunt Ethel couldn’t make it and she would reduce her wedding gift by $200. |

| Dad: | Oh, boy!! |

| Mom: | We’ll have to take them to the Post Office to mail them and that takes a day. Addressing would take 3 days unless we hired some part-time girls and we can’t start until the printer is finished. If we hired the girls we could probably save 2 days by spending $40 for each day saved. |

| Lauren: | We need to get gifts for the bridesmaids. I could spend a day and do that. |

| Mom: | Before we can even start to write out those invitations we need a guest list. Heavens, that will take 4 days to get in order and only I can understand our address file. |

| Lauren: | Oh, Mom, I’m so excited. We can start each of the relatives on a different job. |

| Mom: | Honey, I don’t see how we can do it. Why, I’ve got to choose the invitations and patterns and reserve the church and . . . |

| Dad: | Why don’t you just take $3,000 and elope? Your sister’s wedding cost me $2,400 and she didn’t have to fly people up from Guatemala, hire extra girls and Mrs. Jacks, use airfreight, or anything like that. |

Using the yellow sticky approach shown in Snapshot from Practice 6.1, develop a project network for the “Now” wedding.

Create a schedule for the wedding using MS Project. Can you reach the deadline of January 21 for the “Now” wedding? If you cannot, what would it cost to make the January 21 deadline and which activities would you change?

*This case was adapted from a case originally written by Professor D. Clay Whybark, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C.

Case 9.7

The “Now” Wedding—Part B

Several complications arose during the course of trying to meet the deadline of January 20 for the “Now” wedding rehearsal. Since Lauren was adamant on having the wedding on January 21 (as was Connor for obvious reasons), the implications of each of these complications had to be assessed.

page 353

On January 1 the chairman of the Vestry Committee of the church was left unimpressed by the added donation and said he wouldn’t reduce the notice period from 14 to 7 days.

Mother came down with the 3-day flu as she started working on the guest list January 2.

Bob’s Printing Shop press was down for 1 day on January 5 in order to replace faulty brushes in the electric motor.

The lace and dress material were lost in transit. Notice of the loss was received on January 10.

Could the wedding still take place on January 21? If not, what options were available?

Design elements: Snapshot from Practice, Highlight box, Case icon: ©Sky Designs/Shutterstock

1 Brooks’s The Mythical Man-Month (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1994) is considered a classic on software project management.

2 Gordon, R. L., and J. C. Lamb, “A Close Look at Brooks’ Law,” Datamation, June 1977, pp. 81–86.

3 Linearity assumes that the cost for crashing each day is constant.