page 212

CHAPTER

SEVEN

7

Managing Risk

page 213

You’ve got to go out on a limb sometimes because that’s where the fruit is.

—Will Rogers

Every project manager understands risks are inherent in projects, deliveries are delayed, accidents happen, people get sick, etc. No amount of planning can overcome risk, or the inability to control chance events. In the context of projects, risk is an uncertain event or condition that if it occurs, has a positive or negative effect on project objectives. A risk has a cause and, if it occurs, a consequence. For example, a cause may be a flu virus or change in scope requirements. The event is that team members get stricken with the flu or the product has to be redesigned. If either of these uncertain events occurs, it will impact the cost, schedule, and quality of the project.

Some potential risk events can be identified before the project starts—such as equipment malfunction or change in technical requirements. Risks can be anticipated consequences, like schedule slippages or cost overruns. Risks can be beyond imagination, like the 2008 financial meltdown.

While risks can have positive consequences such as unexpected price reduction in materials, the primary focus of this chapter is on what can go wrong and the risk management process.

page 214

Risk management attempts to recognize and manage potential and unforeseen trouble spots that may occur when the project is implemented. Risk management identifies as many risk events as possible (what can go wrong), minimizes their impact (what can be done about the event before the project begins), manages responses to events that do materialize (contingency plans), and provides contingency funds to cover risk events that actually materialize.

For a humorous, but ultimately embarrassing, example of poor risk management see Snapshot from Practice 7.1: Giant Popsicle Gone Wrong.

7.1 Risk Management Process

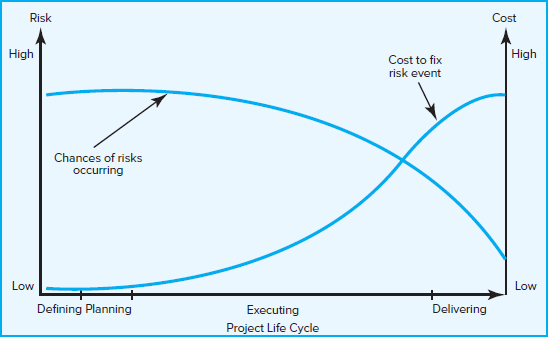

Figure 7.1 presents a graphic model of the risk management challenge. The chances of a risk event occurring (e.g., an error in time estimates, cost estimates, or design technology) are greatest during the early stages of a project. This is when uncertainty is highest and many questions remain unanswered. As the project progresses toward completion, risk declines as the answers to critical issues (Will the technology work? Is the timeline feasible?) are resolved. The cost impact of a risk event, however, increases over the life of the project. For example, the risk event of a design flaw occurring after a prototype has been made has a greater cost or time impact than if the flaw were discovered during the planning phase of the project.

FIGURE 7.1

Risk Event Graph

The cost of mismanaged risk control early on in the project is exemplified by the ill-fated 1999 NASA Mars Climate Orbiter. Investigations revealed that Lockheed Martin had botched the design of critical navigation software. While flight computers on the ground did calculations based on pounds of thrust per second, the spacecraft’s page 215computer software used metric units called newtons. A check to see if the values were compatible was never done. “Our check and balances processes did not catch an error like this that should have been caught,” said Ed Weiler, NASA’s associate administrator for space science. “That is the bottom line” (Orlando Sentinel, 1999). If the error had been discovered early, the correction would have been relatively simple and inexpensive. Instead, the error was never discovered, and after the nine-month journey to the red planet, the $125-million probe approached Mars at too low an altitude and burned up in the planet’s atmosphere.

Following the 1999 debacle, NASA instituted a more robust risk management system, which has produced a string of successful missions to Mars, including the dramatic landing of the Curiosity rover in August 2012.1

Risk management is a proactive, rather than reactive, approach. It is a preventive process designed to ensure that surprises are reduced and that negative consequences associated with undesirable events are minimized. It also prepares the project manager to take action when a time, cost, and/or technical advantage is possible. Successful management of project risk gives the project manager better control over the future and can significantly improve the chances of reaching project objectives on time and within budget and of meeting required technical (functional) performance.

The sources of project risks are unlimited. There are external sources, such as inflation, market acceptance, exchange rates, and government regulations. In practice, these risk events are often referred to as “threats” to differentiate them from those that are not within the project manager’s or team’s responsibility area. (Later we will see that budgets for such risk events are placed in a “management reserve” contingency budget.) Since such external risks are usually considered before the decision to go ahead with the project, they will be excluded from the discussion of project risks. However, external risks are extremely important and must be addressed.

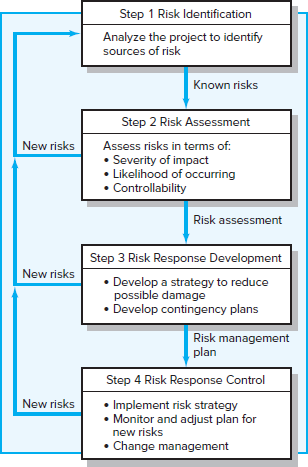

The major components of the risk management process are depicted in Figure 7.2. Each step will be examined in more detail in the remainder of the chapter.

page 216

FIGURE 7.2 The Risk Management Process

7.2 Step 1: Risk Identification

The risk management process begins by trying to generate a list of all the possible risks that could affect the project. Typically the project manager pulls together, during the planning phase, a risk management team consisting of core team members and other relevant stakeholders. Research has demonstrated that groups make more accurate judgments about risks than individuals do (Snizek & Henry, 1989). The team uses brainstorming and other problem identifying techniques to identify potential problems. Participants are encouraged to keep an open mind and generate as many probable risks as possible. More than one project has been bushwhacked by an event that members thought was preposterous in the beginning. Later during the assessment phase, participants will have a chance to analyze and filter out unreasonable risks.

One common mistake that is made early in the risk identification process is to focus on objectives and not on the events that could produce consequences. For example, team members may identify failing to meet schedule as a major risk. What they need to focus on are the events that could cause this to happen (e.g., poor estimates, adverse weather, shipping delays). Only by focusing on actual events can potential solutions be found.

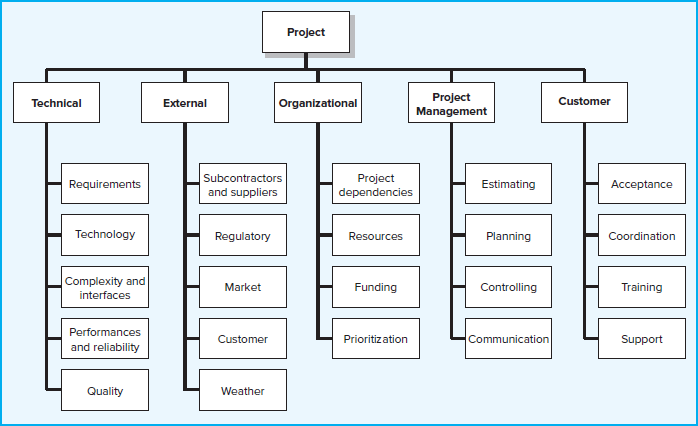

Organizations use risk breakdown structures (RBSs) in conjunction with work breakdown structures (WBSs) to help management teams identify and eventually analyze risks. Figure 7.3 provides a generic example of an RBS. The focus at the beginning should be on risks that can affect the whole project, as opposed to a specific section of the project or network. For example, the discussion of funding may lead the team to identify the possibility of the project budget being cut after the project has page 217started as a significant risk event. Likewise, when discussing the market the team may identify responding to new product releases by competitors as a risk event.

FIGURE 7.3 The Risk Breakdown Structure (RBS)

After the macro risks have been identified, specific areas can be checked. An effective tool for identifying specific risks is the risk breakdown structure. Use of the RBS reduces the chance a risk event will be missed. On large projects multiple risk teams are organized around specific deliverables and submit their risk management reports to the project manager. See Snapshot from Practice 7.2: Terminal 5—London Heathrow Airport* for an example of a project that would have benefited from a more robust RBS.

A risk profile is another useful tool. A risk profile is a list of questions that address traditional areas of uncertainty on a project. These questions have been developed and refined from previous, similar projects. Figure 7.4 provides a partial example of a risk profile.

FIGURE 7.4

Partial Risk Profile for Product Development Project

|

Technical Requirements Are the requirements stable? Design Does the design depend on unrealistic or optimistic assumptions? Testing Will testing equipment be available when needed? Development Is the development process supported by a compatible set of procedures, methods, and tools? Schedule Is the schedule dependent upon the completion of other projects? Budget How reliable are the cost estimates? Quality Are quality considerations built into the design? Management Do people know who has authority for what? Work Environment Do people work cooperatively across functional boundaries? Staffing Is staff inexperienced or understaffed? Customer Does the customer understand what it will take to complete the project? Contractors Are there any ambiguities in contractor task definitions? |

Good risk profiles, like RBSs, are tailored to the type of project in question. For example, building an information system is different from building a new car. They are organization specific. Risk profiles recognize the unique strengths and weaknesses of the firm. Finally, risk profiles address both technical and management risks. For example, the profile shown in Figure 7.4 asks questions about design, such as “Does the design depend upon unrealistic assumptions?” The questions may lead the team to identify that the technology will not work under extreme conditions as a risk. Similarly, questions about work environment (“Do people cooperate across functional boundaries?”) may lead to the identification of potential communication breakdowns between Marketing and R&D as a risk.

Risk profiles are generated and maintained usually by personnel from the project office. They are updated and refined during the post-project audit (see Chapter 14). page 218These profiles, when kept up to date, can be a powerful resource in the risk management process. The collective experience of the firm’s past projects resides in their questions.

Historical records can complement or be used when formal risk profiles are not available. Project teams can investigate what happened on similar projects in the past to identify potential risks. For example, a project manager can check the on-time performance of selected vendors to gauge the threat of shipping delays. IT project managers can access “best practices” papers detailing other companies’ experiences converting software systems. Inquiries should not be limited to recorded data. Savvy project managers tap the wisdom of others by seeking the advice of veteran project managers.

page 219

The risk identification process should not be limited to just the core team. Input from customers, sponsors, subcontractors, vendors, and other stakeholders should be solicited. Relevant stakeholders can be formally interviewed or included on the risk management team. Not only do these players have a valuable perspective, but by involving them in the risk management process they also become more committed to project success.2

One of the keys to success in risk identification is attitude. While a “can do” attitude is essential during implementation, project managers have to encourage critical thinking when it comes to risk identification. The goal is to find potential problems before they happen.

The RBS and risk profiles are useful tools for making sure no stones are left unturned. At the same time, when done well the number of risks identified can be overwhelming and a bit discouraging. Initial optimism can be replaced with griping and cries of “What have we gotten ourselves into?” It is important that project managers set the right tone and complete the risk management process so members regain confidence in themselves and the project.

7.3 Step 2: Risk Assessment

Step 1 produces a list of potential risks. Not all of these risks deserve attention, however. Some are trivial and can be ignored, while others pose serious threats to the welfare of the project. Managers have to develop methods for sifting through the list of risks, eliminating inconsequential or redundant ones and stratifying worthy ones in terms of importance and need for attention.

Scenario analysis is the easiest and most commonly used technique for analyzing risks. Team members assess the significance of each risk event in terms of

Probability of the event.

Impact of the event.

page 220

Simply stated, risks need to be evaluated in terms of the likelihood the event is going to occur and the impact or consequences of its occurrence. A project manager being struck by lightning at a work site would have a major negative impact on the project, but the likelihood of such an event is so low that the risk is not worthy of consideration. Conversely, people do change jobs, so an event like the loss of key project personnel would have not only an adverse impact but also a high likelihood of occurring in some organizations. If so, then it would be wise for that organization to be proactive and mitigate this risk by developing incentive schemes for retaining specialists and/or engaging in cross-training to reduce the impact of turnover.

The quality and credibility of the risk analysis process require that different levels of risk probabilities and impacts be defined. These definitions vary and should be tailored to the specific nature and needs of the project. For example, a relatively simple scale ranging from “very unlikely” to “almost certainly” may suffice for one project, whereas another project may use more precise numeric probabilities (e.g., 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, . . .).

Impact scales can be a bit more problematic, since adverse risks affect project objectives differently. For example, a component failure may cause only a slight delay in project schedule but a major increase in project cost. If controlling cost is a high priority, then the impact would be severe. If, on the other hand, time is more critical than cost, then the impact would be minor.

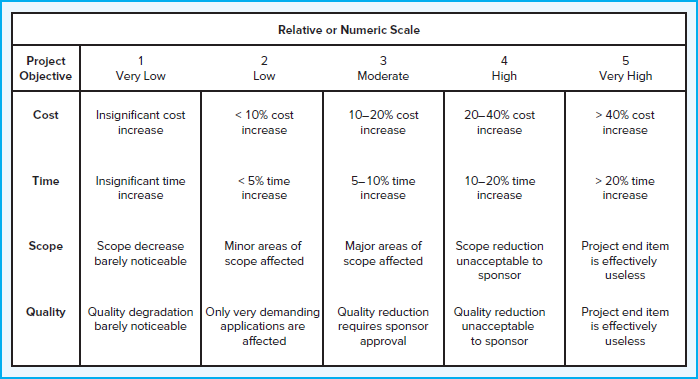

Because impact ultimately needs to be assessed in terms of project priorities, different kinds of impact scales are used. Some scales may simply use rank-order descriptors, such as “low,” “moderate,” “high,” and “very high,” whereas others use numeric weights (e.g., 1–10). Some may focus on the project in general, whereas others focus on specific project objectives. The risk management team needs to establish up front what distinguishes a 1 from a 3 or “moderate” impact from “severe” impact. Figure 7.5 page 221provides an example of how impact scales could be defined, given the project objectives of cost, time, scope, and quality.

FIGURE 7.5 Defined Conditions for Impact Scales of a Risk on Major Project Objectives (examples for negative impacts only)

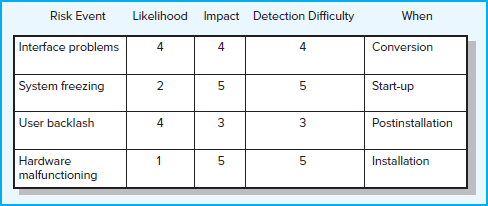

Documentation of scenario analyses can be seen in various risk assessment forms used by companies. Figure 7.6 is a partial example of a risk assessment form used on an information systems project involving an operating systems (OS) upgrade.

FIGURE 7.6 Risk Assessment Form

Notice that in addition to evaluating the severity and probability of risk events the team also assesses when the event might occur and its detection difficulty. Detection difficulty is a measure of how easy it would be to detect that the event was going to occur in time to take mitigating action, that is, how much warning there would be. So in the OS upgrade example, the detection scale would range from 5 = no warning to 1 = lots of time to react.

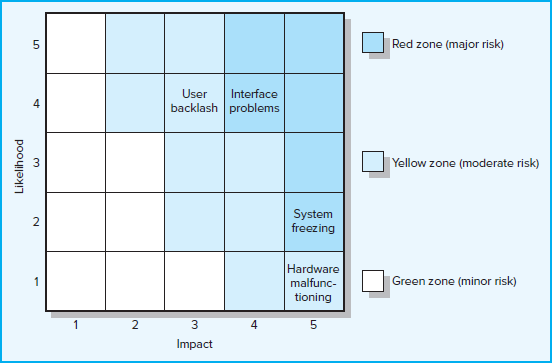

Often organizations find it useful to categorize the severity of different risks into some form of risk assessment matrix. The matrix is typically structured around the impact and likelihood of the risk event. For example, the risk matrix presented in Figure 7.7 consists of a 5 × 5 array of elements with each element representing a different set of impact and likelihood values.

FIGURE 7.7 Risk Severity Matrix

page 222

The matrix is divided into red, yellow, and green zones representing major, moderate, and minor risks, respectively. The red zone is centered on the top right corner of the matrix (high impact/high likelihood), while the green zone is centered on the bottom left corner (low impact/low likelihood). The moderate-risk yellow zone extends down the middle of the matrix. Since impact is generally considered more important than likelihood (a 10 percent chance of losing $1,000,000 is usually considered a more severe risk than a 90 percent chance of losing $1,000), the red zone (major risk) extends farther down the high-impact column.

Using the OS upgrade project again as an example, interface problems and system freezing would be placed in the red zone (major risk), while user backlash and hardware malfunctioning would be placed in the yellow zone (moderate risk).

The risk severity matrix provides a basis for prioritizing which risks to address. Red zone risks receive first priority followed by yellow zone risks. Green zone risks are typically considered inconsequential and ignored unless their status changes.

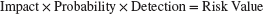

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (fmea) extends the risk severity matrix by including ease of detection in the equation:

Each of the three dimensions is rated according to a 5-point scale. For example, detection is defined as the ability of the project team to discern that the risk event is imminent. A score of 1 would be given if even a chimpanzee could spot the risk coming. The highest detection score of 5 would be given to events that could only be discovered after it was too late (e.g., system freezing). Similar anchored scales would be applied for severity of impact and the probability of the event occurring. The weighting of the risks is then based on their overall score. For example, a risk with an impact in the “1” zone with a very low probability and an easy detection score might score a 1 (1 × 1 × 1 = 1). Conversely, a high-impact risk that is highly probable and impossible to detect would score 125 (5 × 5 × 5 = 125). This broad range of numeric scores allows for easy stratification of risk according to overall significance.

No assessment scheme is absolutely foolproof. For example, the weakness of the FMEA approach is that a risk event rated Impact = 1, Probability = 5, and Detection = 5 would receive the same weighted score as an event rated Impact = 5, Probability = 5, and Detection = 1! This underscores the importance of not treating risk assessment as simply an exercise in mathematics. There is no substitute for thoughtful discussion of key risk events.

Probability Analysis

There are many statistical techniques available to the project manager that can assist in assessing project risk. Decision trees have been used to assess alternative courses of action using expected values. Statistical variations of net present value (NPV) have been used to assess cash flow risks in projects. Correlations between past projects’ cash flow and S-curves (cumulative project cost curve—baseline—over the life of the project) have been used to assess cash flow risks.

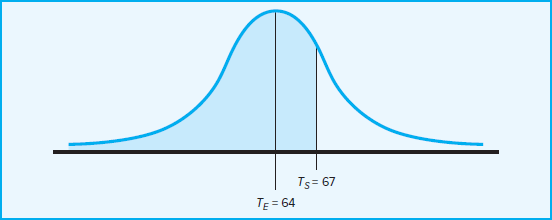

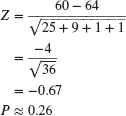

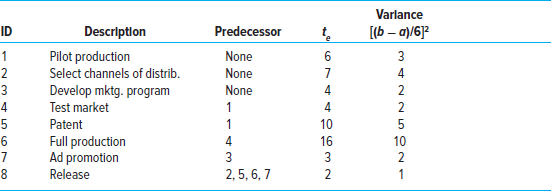

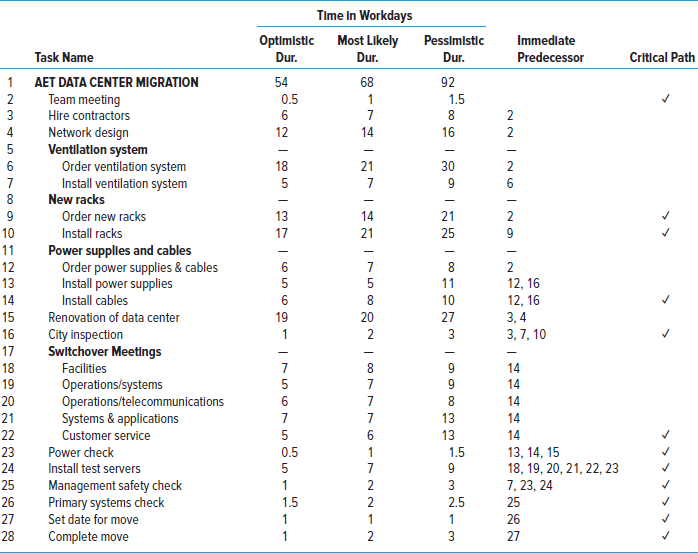

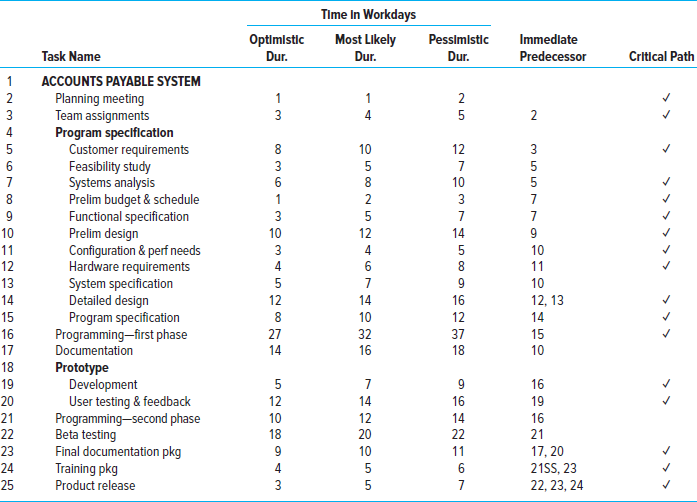

PERT (program evaluation and review technique) and PERT simulation can be used to review activity and project risk. PERT and related techniques take a more macro perspective by looking at overall cost and schedule risks. Here the focus is not on individual events but on the likelihood the project will be completed on time and within budget. These methods are useful in assessing the overall risk of the project and the need for such things as contingency funds, resources, and time. The use of PERT simulation is increasing because it uses the same data required for PERT, and software to perform the simulation is readily available.

page 223

Basically PERT simulation assumes a statistical distribution (range between optimistic and pessimistic) for each activity duration; it then simulates the network (perhaps over 1,000 simulations) using a random number generator. The outcome is the relative probability, called a criticality index, of an activity becoming critical under the many different possible activity durations for each activity. PERT simulation also provides a list of potential critical paths and their respective probabilities of occurring. Having this information available can greatly facilitate identifying and assessing schedule risk. (See Appendix 7.1 at the end of this chapter for a more detailed description and discussion.)

7.4 Step 3: Risk Response Development

When a risk event is identified and assessed, a decision must be made concerning which response is appropriate for the specific event. Responses to risk can be classified as mitigating, avoiding, transferring, escalating, or retaining.

Mitigating Risk

Reducing risk is usually the first alternative considered. There are basically two strategies for mitigating risk: (1) reduce the likelihood that the event will occur and/or (2) reduce the impact that the adverse event would have on the project. Most risk teams focus first on reducing the likelihood of risk events, since if successful this may eliminate the need to consider the potentially costly second strategy.

Testing and prototyping are frequently used to prevent problems from surfacing later in a project. An example of testing can be found in an information systems project. The project team was responsible for installing a new operating system in their parent company. Before implementing the project, the team tested the new system on a smaller, isolated network. By doing so they discovered a variety of problems and were able to come up with solutions prior to implementation. The team still encountered problems with the installation, but the number and severity were greatly reduced.

Often, identifying the root causes of an event is useful. For example, the fear that a vendor will be unable to supply customized components on time may be attributable to (1) poor vendor relationships, (2) design miscommunication, and (3) lack of motivation. As a result of this analysis the project manager may decide to take his counterpart to lunch to clear the air, invite the vendor to attend design meetings, and restructure the contract to include incentives for on-time delivery.

Other examples of reducing the probability of risks occurring are scheduling outdoor work during the summer months, investing in up-front safety training, and choosing high-quality materials and equipment.

When the concerns are that duration and costs have been underestimated, managers will augment estimates to compensate for the uncertainties. It is common to use a ratio between old and new projects to adjust time or cost. The ratio typically serves as a constant. For example, if past projects have taken 10 minutes per line of computer code, a constant of 1.10 (which represents a 10 percent increase) would be used for the proposed project time estimates because the new project is more difficult than prior projects.

An alternative mitigation strategy is to reduce the impact of the risk if it occurs. For example, a bridge-building project illustrates risk reduction. A new bridge project for a coastal port was to use an innovative, continuous cement-pouring process developed by an Australian firm to save large sums of money and time. The major risk was that the continuous pouring process for each major section of the bridge could not be interrupted. Any interruption would require that the whole cement section (hundreds of cubic yards) be torn down and started over. An assessment of possible risks centered page 224on delivery of the cement from the cement factory. Trucks could be delayed, or the factory could break down. Such risks would result in tremendous rework costs and delays. Risk was reduced by having two additional portable cement plants built nearby on different highways within 20 miles of the bridge project in case the main factory supply was interrupted. These two portable plants carried raw materials for a whole bridge section, and extra trucks were on immediate standby each time continuous pouring was required. Similar risk reduction scenarios are apparent in system and software development projects where parallel innovation processes are used in case one fails.

Snapshot from Practice 7.3: From Dome to Dust details the steps Controlled Demolition took to minimize damage when they imploded the Seattle Kingdome.

page 225

Avoiding Risk

Avoiding risk is changing the project plan to eliminate the risk or condition. Although it is impossible to eliminate all risk events, some specific risks may be avoided before you launch the project. For example, adopting proven technology instead of experimental technology can eliminate technical failure. Choosing an Australian supplier as opposed to an Indonesian supplier would virtually eliminate the chance that political unrest would disrupt the supply of critical materials. Likewise, one could eliminate the risk of choosing the wrong software by developing web applications using both ASAP.NET and PHP. Choosing to move a concert indoors would eliminate the threat of inclement weather.

Transferring Risk

Transferring risk to another party is common; this transfer does not change risk. Passing risk to another party almost always results in paying a premium for this exemption. Fixed-price contracts are the classic example of transferring risk from an owner to a contractor. The contractor understands her firm will pay for any risk event that materializes; therefore, a monetary risk factor is added to the contract bid price. Before deciding to transfer risk, the owner should decide which party can best control activities that would lead to the risk occurring. Also, is the contractor capable of absorbing the risk? Clearly identifying and documenting responsibility for absorbing risk is imperative.

Another, more obvious way to transfer risk is insurance. However, in most cases this is impractical because defining the project risk event and conditions to an insurance broker who is unfamiliar with the project is difficult and usually expensive. Of course, low-probability and high-consequence risk events such as acts of God are more easily defined and insured. Performance bonds, warranties, and guarantees are other financial instruments used to transfer risk.

On large, international construction projects like petrochemical plants and oil refineries, host countries are insisting on contracts that enforce Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT) provisions. Here the prime project organization is expected not only to build the facility but also to take over ownership until its operation capacity has been proven and all the debugging has occurred before final transfer of ownership to the client. In such cases, the host country has transferred financial risk of ownership until the project has been completed and capabilities proven.

Escalating Risk

Escalating risk occurs when the project encounters a threat that is outside the scope of the project or the authority of the project manager. In such cases the response should be to notify the appropriate people within the organization of the threat. For example, while working on a high-tech product an engineer discovers through informal channels that a competitor is developing an alternative energy source. While this would not impact the current project, it may have significant implications for future products. The project manager would forward this information to the product manager and head of R&D. In another example, informal discussions with team members reveal widespread dissatisfaction with pay and benefits among staff across the company. This threat would be escalated to the Human Resource Department. Escalated risks are not monitored further by the project team.

Retaining Risk

Retaining risk occurs when a conscious decision is made to accept the risk of an event occurring. Some risks are so large it is not feasible to consider transferring or page 226reducing the event (e.g., an earthquake). The project owner assumes the risk because the chance of such an event occurring is slim. In other cases risks identified in the budget reserve can simply be absorbed if they materialize. The risk is retained by developing a contingency plan to implement if the risk materializes. In a few cases a risk event can be ignored and a cost overrun accepted, should the risk event occur.

People vary in their risk tolerance. Before deciding how to respond to a risk, one should consider the risk appetite of key stakeholders as well as your team.

In the project management lexicon, mitigating a risk refers to a very specific strategy of reducing the probability and/or impact of the threat. However, in any everyday language, mitigating refers to any action that reduces or diminishes a risk, which could include the other responses.

7.5 Contingency Planning

A contingency plan is an alternative plan that will be used if a possible foreseen risk event becomes a reality. The contingency plan represents actions that will reduce or mitigate the negative impact of the risk event. A key distinction between a risk response and a contingency plan is that a response is part of the actual implementation plan and action is taken before the risk can materialize, while a contingency plan is not part of the initial implementation plan and only goes into effect after the risk is recognized.

Like all plans, the contingency plan answers the questions of what, where, when, and how much action will take place. The absence of a contingency plan, when a risk event occurs, can cause a manager to delay or postpone the decision to implement a remedy. This postponement can lead to panic and acceptance of the first remedy suggested. Such after-the-event decision making under pressure can be dangerous and costly. Contingency planning evaluates alternative remedies for possible foreseen events before the risk event occurs and selects the best plan among alternatives. This early contingency planning facilitates a smooth transition to the remedy or work-around plan. The availability of a contingency plan can significantly increase the chances for project success.

Conditions for activating the implementation of the contingency plan should be decided and clearly documented. The plan should include a cost estimate and identify the source of funding. All parties affected should agree to the contingency plan and have authority to make commitments. Because implementation of a contingency plan embodies disruption in the sequence of work, all contingency plans should be communicated to team members so that surprise and resistance are minimized.

Here is an example: A high-tech niche computer company intends to introduce a new “platform” product at a very specific target date. The project’s 47 teams all agree delays will not be acceptable. Their contingency plans for two large component suppliers demonstrate how seriously risk management is viewed. One supplier’s plant sits on the San Andreas Fault, which is prone to earthquakes. The contingency plan has an alternative supplier, who is constantly updated, producing a replica of the component in another plant. Another key supplier in Toronto, Canada, presents a delivery risk on their due date because of potential bad weather. This contingency plan calls for a chartered plane (already contracted to be on standby) if overland transportation presents a delay problem. To outsiders these plans must seem a bit extreme, but in high-tech industries where time to market is king, risks of identified events are taken seriously.

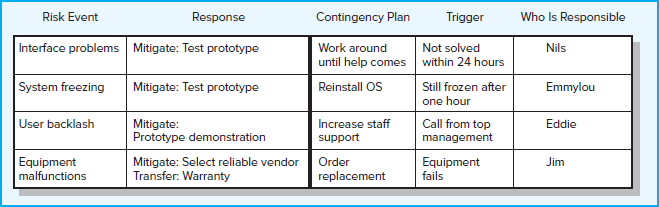

Risk response matrices such as the one shown in Figure 7.8 are useful for summarizing how the project team plans to manage risks that have been identified. Again, the page 227OS upgrade project is used to illustrate this kind of matrix. The first step is to identify whether to mitigate, avoid, transfer, escalate, or retain the risk. The team decides to reduce the chances of the system freezing by experimenting with a prototype of the system. Prototype experimentation not only allows them to identify and fix conversion “bugs” before the actual installation but also yields information that could be useful in enhancing acceptance by end users. The project team is then able to identify and document changes between the old and new systems that will be incorporated into the training the users receive. The risk of equipment malfunction is transferred by choosing a reliable supplier with a strong warranty program.

FIGURE 7.8 Risk Response Matrix

The next step is to identify contingency plans in case the risk still occurs. For example, if interface problems prove insurmountable, then the team will attempt a work-around until vendor experts arrive to help solve the problem. If the system freezes after installation, the team will first try to reinstall the software. If user dissatisfaction is high, then the Information Systems (IS) Department will provide more staff support. If the team is unable to get reliable equipment from the original supplier, then it will order a different brand from a second dealer. The team also needs to discuss and agree what would “trigger” implementation of the contingency plan. In the case of the system freezing, the trigger is not being able to unfreeze the system within one hour or, in the case of user backlash, an angry call from top management. Finally, the individual responsible for monitoring the potential risk and initiating the contingency plan needs to be assigned. Smart project managers establish protocols for contingency responses before they are needed. For an example of the importance of establishing protocols, see Snapshot from Practice 7.4: Risk Management at the Top of the World.

Some of the most common methods for handling risk are discussed in the following sections.

Technical Risks

Technical risks are problematic; they can often be the kind that cause the project to be shut down. What if the system or process does not work? Contingency plans are made for those possibilities that are foreseen. For example, Carrier Transicold was involved in developing a new Phoenix refrigeration unit for truck-trailer applications. This new unit was to use rounded panels made of bonded metals, which at the time was new technology for Transicold. Furthermore, one of its competitors had tried unsuccessfully to incorporate similar bonded metals into their products. The project team was eager to make the new technology work, but it wasn’t until the very end of the project that they were able to get the new adhesives to bond adequately to complete page 228the project. Throughout the project, the team maintained a welded-panel fabrication approach just in case they were unsuccessful. If this contingency approach had been needed, it would have increased production costs, but the project still would have been completed on time.

In addition to backup strategies, project managers need to develop methods to quickly assess whether technical uncertainties can be resolved. The use of sophisticated computer-aided design (CAD) software has greatly helped resolve design page 229problems. At the same time, Smith and Reinertsen (1995), in their book Developing Products in Half the Time, argue that there is no substitute for making something and seeing how it works, feels, or looks. They suggest that one should first identify the high-risk technical areas, then build models or design experiments to resolve the risk as quickly as possible. Technology offers many methods for early testing and validation, ranging from 3-D printing and holographic imagery for model building to focus groups and early design usability testing for market testing (Thamhain, 2013). By isolating and testing the key technical questions early in a project, project feasibility can be quickly determined and necessary adjustments made, such as reworking the process or in some cases closing down the project.3

Schedule Risks

Often organizations will defer the threat of a project coming in late until it surfaces. Here contingency funds are set aside to expedite or “crash” the project to get it back on track. Crashing, or reducing project duration, is accomplished by shortening (compressing) one or more activities on the critical path. This comes with additional costs and risk. Techniques for managing this situation are discussed in Chapter 9. Some contingency plans can avoid costly procedures. For example, schedules can be altered by working activities in parallel or using start-to-start lag relationships. Also, using the best people for high-risk tasks can relieve or lessen the chance of some risk events occurring.

Cost Risks

Projects of long duration need some contingency for price changes—which are usually upward. The important point to remember when reviewing price is to avoid the trap of using one lump sum to cover price risks. For example, if inflation has been running about 3 percent, some managers add 3 percent for all resources used in the project. This lump-sum approach does not address exactly where price protection is needed and fails to provide for tracking and control. On cost-sensitive projects, price risks should be evaluated item by item. Some purchases and contracts will not change over the life of the project. Those that may change should be identified and estimates made of the magnitude of change. This approach ensures control of the contingency funds as the project is implemented.

Funding Risks

What if the funding for the project is cut by 25 percent or completion projections indicate that costs will greatly exceed available funds? What are the chances of the project being canceled before completion? Seasoned project managers recognize that a complete risk assessment must include an evaluation of funding supply. This is especially true for publicly funded projects. Case in point was the ill-fated ARH-70 Arapaho helicopter being developed for the U.S. Army by BellAircraft. Over $300 million had been invested to develop a new age combat and reconnaissance helicopter, when in October 2008 the Defense Department recommended that the project be canceled. The cancellation reflected a need to cut costs and a switch toward using unmanned aircraft for surveillance as well as attack missions.

Just as government projects are subject to changes in strategy and political agenda, business firms frequently undergo changes in priorities and top management. The page 230pet projects of the new CEO replace the pet projects of the former CEO. Resources become tight, and one way to fund new projects is to cancel other projects.

Severe budget cuts or lack of adequate funding can have a devastating effect on a project. Typically when such a fate occurs, there is a need to scale back the scope of the project to what is possible. “All-or-nothing projects” are ripe targets to budget cutters. This was the case of the Arapaho helicopter once the decision was made to move away from manned reconnaissance aircraft. Here the “chunkability” of the project can be an advantage. For example, freeway projects can fall short of the original intentions but still add value for each mile completed.

On a much smaller scale, similar funding risks may exist for more mundane projects. For example, a building contractor may find that due to a sudden downturn in the stock market the owners can no longer afford to build their dream house. Or an IS consulting firm may be left empty handed when a client files for bankruptcy. In the former case the contractor may have as a contingency selling the house on the open market, while unfortunately, the consulting firm will have to join the long line of creditors.

7.6 Opportunity Management

For the sake of brevity, this chapter has focused on negative risks—what can go wrong on a project. There is a flip side—what can go right on a project. This is commonly referred to as a positive risk or an opportunity. An opportunity is an event that can have a positive impact on project objectives. For example, unusually favorable weather can accelerate construction work, or a drop in fuel prices may create savings that could be used to add value to a project. Essentially the same process that is used to manage negative risks is applied to positive risks. Opportunities are identified, assessed in terms of likelihood and impact, responses are determined, and even contingency plans and funds can be established to take advantage of the opportunity if it occurs. The major exception between managing negative risks and opportunity is in the responses. The project management profession has identified five types of response to an opportunity:4

Exploit. This tactic seeks to eliminate the uncertainty associated with an opportunity to ensure that it definitely happens. Examples include assigning your best personnel to a critical burst activity to reduce the time to completion and revising a design to enable a component to be purchased rather than developed internally.

Share. This strategy involves allocating some or all of the ownership of an opportunity to another party who is best able to capture the opportunity for the benefit of the project. Examples include continuous improvement incentives for external contractors and joint ventures.

Enhance. Enhance is the opposite of mitigate in that action is taken to increase the probability and/or the positive impact of an opportunity. Examples include choosing a site location based on favorable weather patterns and choosing raw materials that are likely to decline in price.

Escalate. Sometimes projects encounter opportunities that are outside the scope of the project or exceed the authority of the project manager. In such cases the project manager should notify the appropriate people within the organization of the opportunity. For example, a customer tells the project manager that he is considering adapting the product to a different market and wonders whether you would be interested in bidding on the work. The opportunity is passed upward to the project page 231sponsor. Or through the course of project interactions, the project manager discovers an alternative supplier for a key component. This information would be passed on to the Procurement Department.

Accept. Accepting an opportunity is being willing to take advantage of it if it occurs, but not taking action to pursue it.

While it is only natural to focus on negative risks, it is sound practice to engage in active opportunity management as well.

7.7 Contingency Funding and Time Buffers

Contingency funds are established to cover project risks—identified and unknown. When, where, and how much money will be spent are not known until the risk event occurs. Project “owners” are often reluctant to set up project contingency funds that seem to imply the project plan might be a poor one. Some perceive the contingency fund as an add-on slush fund. Others say they will face the risk when it materializes. Usually such reluctance to establish reserve funds can be overcome with documented risk identification, assessment, contingency plans, and plans for when and how funds will be disbursed.

The size and amount of contingency funds depend on uncertainty inherent in the project. Uncertainty is reflected in the “newness” of the project, inaccurate time and cost estimates, technical unknowns, unstable scope, and problems not anticipated. In practice, contingencies run from 1 to 10 percent in projects similar to past projects. However, in unique and high-technology projects it is not uncommon to find contingencies running in the 20 to 60 percent range. Use and rate of consumption of reserves must be closely monitored and controlled. Simply picking a percentage of the baseline—say, 5 percent—and calling it the contingency reserve is not a sound approach. Also, adding up all the identified contingency allotments and throwing them into one pot is not conducive to sound control of the reserve fund.

In practice, the contingency fund is typically divided into contingency and management reserve funds for control purposes. Contingency reserves are set up to cover identified risks; these reserves are allocated to specific segments or deliverables of the project. Management reserves are set up to cover unidentified risks and are allocated to risks associated with the total project. The risks are separated because their use requires approval from different levels of project authority. Because all risks are probabilistic, the reserves are not included in the baseline for each work package or activity; they are only activated when a risk occurs. If an identified risk does not occur and its chance of occurring is past, the fund allocated to the risk should be deducted from the contingency reserves. (This removes the temptation to use contingency reserves for other issues or problems.) Of course, if the risk does occur, funds are removed from the reserve and added to the cost baseline.

It is important that contingency allowances be independent of the original time and cost estimates. These allowances need to be clearly distinguished to avoid time and budget game playing.

Contingency Reserves

These reserves are identified for specific work packages or segments of a project found in the baseline budget or work breakdown structure. For example, a reserve amount might be added to “computer coding” to cover the risk of “testing” showing a coding problem. The reserve amount is determined by costing out the accepted contingency page 232or recovery plan. The contingency reserves should be communicated to the project team. This openness suggests trust and encourages good cost performance. However, distributing contingency reserves should be the responsibility of both the project manager and the team members responsible for implementing the specific segment of the project. If the risk does not materialize, the funds are removed from the contingency reserves. Thus, contingency reserves decrease as the project progresses.

Management Reserves

These reserve funds are needed to cover major unforeseen risks and, hence, are applied to the total project. For example, a major scope change may appear necessary midway in the project. Because this change was not anticipated, it is covered from the management reserves. Management reserves are established after contingency reserves are identified and funds established. These reserves are independent of contingency reserves and are controlled by the project manager and the “owner” of the project. The “owner” can be internal (top management) or external to the project organization. Most management reserves are set using historical data and judgments concerning the uniqueness and complexity of the project.

Placing technical contingencies in the management reserves is a special case. Identifying possible technical (functional) risks is often associated with a new, untried, innovative process or product. Because there is a chance the innovation may not work out, a fallback plan is necessary. This type of risk is beyond the control of the project manager. Hence, technical reserves are held in the management reserves and controlled by the owner or top management. The owner and project manager decide when the contingency plan will be implemented and the reserve funds used. It is assumed there is a high probability these funds will never be used.

Table 7.1 shows the development of a budget estimate for a hypothetical project. Note how contingency and management reserves are kept separate; control is easily tracked using this format.

TABLE 7.1

Budget Estimate

| Activity | Budget Baseline |

Contingency Reserve |

Project Budget |

| Design | $500,000 | $15,000 | $515,000 |

| Code | 900,000 | 80,000 | 980,000 |

| Test | 20,000 | 2,000 | 22,000 |

| Subtotal | $1,420,000 | $97,000 | $1,517,000 |

| Management reserve | — | — | 50,000 |

| Total | $1,420,000 | $97,000 | $1,567,000 |

Time Buffers

Just as contingency funds are established to absorb unplanned costs, managers use time buffers to cushion against potential delays in the project. And like contingency funds, the amount of time is dependent upon the inherent uncertainty of the project. The more uncertain the project is, the more time should be reserved for the schedule. The strategy is to assign extra time at critical moments in the project. For example, buffers are added to

Activities with severe risks.

Merge activities that are prone to delays due to one or more preceding activities being late.

page 233 Noncritical activities to reduce the likelihood that they will create another critical path.

Activities that require scarce resources to ensure that the resources are available when needed.

In the face of overall schedule uncertainty, buffers are sometimes added to the end of the project. For example, a 300-working-day project may have a 30-day project buffer. While the extra 30 days would not appear on the schedule, they are available if needed. Like management reserves, this buffer typically requires the authorization of top management. A more systematic approach to buffer management is discussed in the Chapter 8 appendix on critical-chain project management.

7.8 Step 4: Risk Response Control

Typically the results of the first three steps of the risk management process are summarized in a formal document often called the risk register. A risk register details all identified risks, including descriptions, category, probability of occurring, impact, responses, contingency plans, owners, and current status. The register is the backbone for the last step in the risk management process: risk control. Risk control involves executing the risk response strategy, monitoring triggering events, initiating contingency plans, and watching for new risks. Establishing a change management system to deal with events that require formal changes in the scope, budget, and/or schedule of the project is an essential element of risk control.

Project managers need to monitor risks just as they track project progress. Risk assessment and updating need to be part of every status meeting and progress report system. The project team needs to be on constant alert for new, unforeseen risks. Thamhain (2013) studied 35 major product development efforts and found that over half of the contingencies that occurred were not anticipated! Readiness to respond to the unexpected is a critical element of risk management.

Management needs to be sensitive that others may not be forthright in acknowledging new risks and problems. Admitting that there might be a bug in design code or that different components are not compatible reflects poorly on individual performance. If the prevailing organizational culture is one where mistakes are punished severely, then it is only human nature to protect oneself. Similarly, if bad news is greeted harshly and there is a propensity to “kill the messenger,” then participants will be reluctant to speak freely. The tendency to suppress bad news is compounded when individual responsibility is vague and the project team is under extreme pressure from top management to get the project done quickly.

Project managers need to establish an environment in which participants feel comfortable raising concerns and admitting mistakes (Browning & Ramasesh, 2015). The norm should be that mistakes are acceptable and hiding mistakes is intolerable. Problems should be embraced, not denied. Participants should be encouraged to identify problems and new risks. A positive attitude by the project manager toward risks is key.

On large, complex projects it may be prudent to repeat the risk identification/assessment exercise with fresh information. Risk profiles should be reviewed to test if the original responses held true. Relevant stakeholders should be brought into the discussion and the risk register needs to be updated. While this may not be practical on an ongoing basis, project managers should touch base with them on a regular basis or hold special stakeholder meetings to review the status of risks on the project.

page 234

A second key for controlling the cost of risks is documenting responsibility. This can be problematic in projects involving multiple organizations and contractors. Responsibility for risk is frequently passed on to others with the statement “That is not my worry.” This mentality is dangerous. Each identified risk should be assigned (or shared) by mutual agreement of the owner, project manager, and the contractor or person having line responsibility for the work package or segment of the project. It is best to have the line person responsible approve the use of contingency reserves and monitor their rate of usage. If management reserves are required, the line person should play an active role in estimating additional costs and funds needed to complete the project. Having line personnel participate in the process focuses attention on the management reserves, control of their rate of usage, and early warning of potential risk events. If risk management is not formalized, responsibility and responses to risk will be ignored.

The bottom line is that project managers and team members need to be vigilant in monitoring potential risks and should identify new land mines that could derail a project. Risk assessment has to be part of the working agenda of status meetings, and when new risks emerge they need to be analyzed and incorporated into the risk management process.

7.9 Change Control Management

A major element of the risk control process is change management. Not every detail of a project plan will materialize as expected. Coping with and controlling project changes present a formidable challenge for most project managers. Changes come from many sources, such as the project customer, owner, project manager, team members, and risk events. Most changes easily fall into three categories:

Scope changes in the form of design or additions represent big changes—for example, customer requests for a new feature or a redesign that will improve the product.

Implementation of contingency plans, when risk events occur, represent changes in baseline costs and schedules.

Improvement changes suggested by project team members represent another category.

Because change is inevitable, a well-defined change review and control process should be set up early in the project planning cycle.

Change management systems involve reporting, controlling, and recording changes to the project baseline. (Note: Some organizations consider change control systems part of configuration management.) In practice, most change management systems are designed to accomplish the following.

Identify proposed changes.

List expected effects of proposed change(s) on schedule and budget.

Review, evaluate, and approve or disapprove changes formally.

Negotiate and resolve conflicts of change, conditions, and cost.

Communicate changes to the parties affected.

Assign responsibility for implementing change.

page 235 Adjust the master schedule and budget.

Track all changes that are to be implemented.

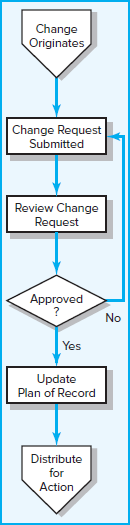

As part of the project communication plan, stakeholders define up front the communication and decision-making process that will be used to evaluate and accept changes. The process can be captured in a flow diagram like the one in Figure 7.9. On small projects this process may simply entail approval of a small group of stakeholders. On larger projects more elaborate decision-making processes are established, with different processes being used for different kinds of change. For example, changes in performance requirements may require multiple sign-offs, including the project sponsor and client, while switching suppliers may be authorized by the project manager. Regardless of the nature of the project, the goal is to establish the process for introducing necessary changes in the project in a timely and effective manner.

FIGURE 7.9 Change Control Process

Of particular importance is assessing the impact of the change on the project. Often solutions to immediate problems have adverse consequences on other aspects of a project. For example, in overcoming a problem with the exhaust system for a hybrid automobile, the design engineers contributed to the prototype exceeding weight parameters. It is important that the implications of changes are assessed by people with appropriate expertise and perspective. On construction projects this is often the responsibility of the architecture firm, while “software architects” perform a similar function on software development efforts.

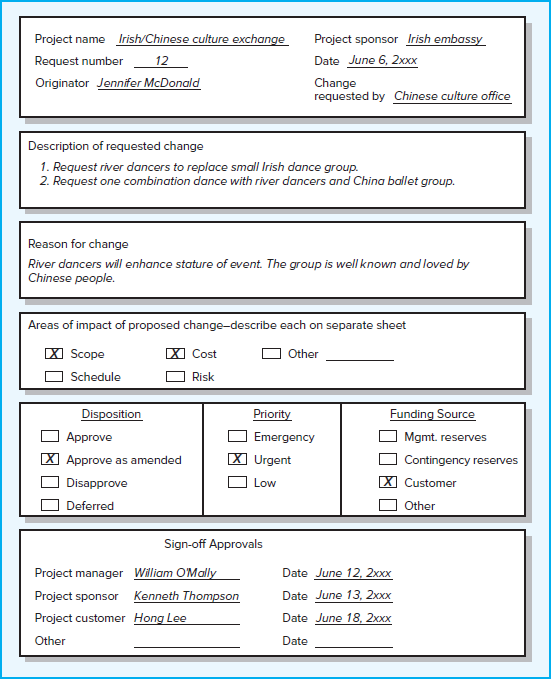

Organizations use change request forms and logs to track proposed changes. An example of a simplified change request form is depicted in Figure 7.10. Typically change request forms include a description of the change, the impact of not approving the change, the impact of the change on project scope/schedule/cost, and defined signature paths for review, as well as a tracking log number.

FIGURE 7.10

Sample Change Request

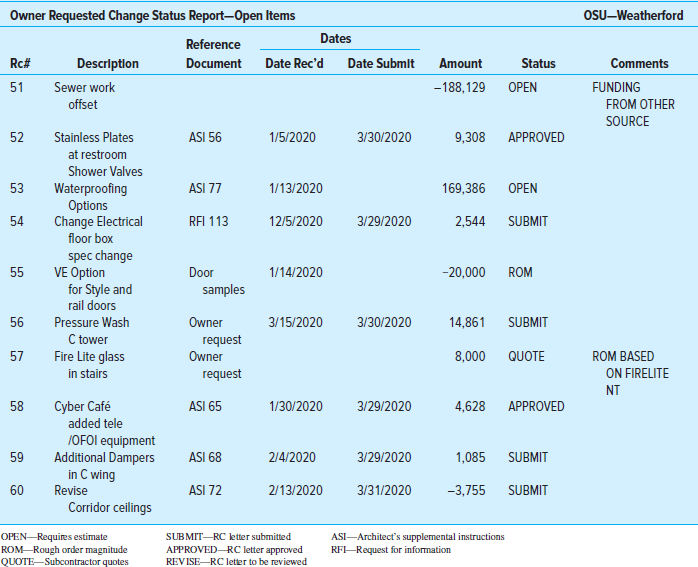

An abridged version of a change request log for a construction project is presented in Figure 7.11. These logs are used to monitor change requests. They typically summarize the status of all outstanding change requests and include such useful information as the source and date of the change, document codes for related information, cost estimates, and the current status of the request.

FIGURE 7.11 Change Request Log

Every approved change must be identified and integrated into the plan of record through changes in the project WBS and baseline schedule. The plan of record is the current official plan for the project in terms of scope, budget, and schedule. The plan of record serves as a change management benchmark for future change requests as well as the baseline for evaluating project progress.

If the change control system is not integrated with the WBS and baseline, project plans and control will soon self-destruct. Thus, one of the keys to a successful change control process is document, document, document! The benefits derived from change control systems are the following.

Inconsequential changes are discouraged by the formal process.

Costs of changes are maintained in a log.

Integrity of the WBS and performance measures is maintained.

Allocation and use of contingency and management reserves are tracked.

Responsibility for implementation is clarified.

Effect of changes is visible to all parties involved.

page 236 Implementation of change is monitored.

Scope changes will be quickly reflected in baseline and performance measures.

Clearly change control is important and requires that someone or some group be responsible for approving changes, keeping the process updated, and communicating changes to the project team and relevant stakeholders. Project control depends heavily on keeping the change control process current. This historical record can be used for satisfying customer inquiries, identifying problems in post-project audits, and estimating future project costs.

page 237

Summary

To put the processes discussed in this chapter in proper perspective, one should recognize that the essence of project management is risk management. Every technique in this book is a risk management technique. Each in its own way tries to prevent something bad from happening. Project selection systems try to reduce the likelihood that projects will not contribute to the mission of the firm. Project scope statements, among other things, are designed to avoid costly misunderstandings and reduce scope creep. Work breakdown structures reduce the likelihood that some vital part of the project will be omitted or that the budget estimates are unrealistic. Team building reduces the likelihood of dysfunctional conflict and breakdowns in coordination. All of the techniques try to increase stakeholder satisfaction and the chances of project success.

page 238

From this perspective, managers engage in risk management activities to compensate for the uncertainty inherent in project management and that things never go according to plan. Risk management is proactive, not reactive. It reduces the number of surprises and prepares people for the unexpected.

Although many managers believe that in the final analysis, risk assessment and contingency depend on subjective judgment, some standard method for identifying, assessing, and responding to risks should be included in all projects. The very process of identifying project risks forces some discipline at all levels of project management and improves project performance.

Contingency plans increase the chance that the project can be completed on time and within budget. Contingency plans can be simple work-arounds or elaborate, detailed plans. Responsibility for risks should be clearly identified and documented. It is desirable and prudent to keep a reserve as a hedge against project risks. Contingency reserves are linked to the WBS and should be communicated to the project team. Control of management reserves should remain with the owner, project manager, and line person responsible. Use of contingency reserves should be closely monitored, controlled, and reviewed throughout the project life cycle.

Experience clearly indicates that using a formal, structured process to handle possible foreseen and unforeseen project risk events minimizes surprises, costs, delays, stress, and misunderstandings. Risk management is an iterative process that occurs throughout the lifespan of the project. When risk events occur or changes are necessary, using an effective change control process to quickly approve and record changes will facilitate measuring performance against schedule and cost. Ultimately, successful risk management requires a culture in which threats are embraced, not denied, and problems are identified, not hidden.

Key Terms

Review Questions

Project risks can/cannot be eliminated if the project is carefully planned. Explain.

The chances of risk events occurring and their respective costs increasing change over the project life cycle. What is the significance of this phenomenon to a project manager?

What is the difference between avoiding a risk and retaining a risk?

What is the difference between risk mitigation and contingency planning?

Explain the difference between contingency reserves and management reserves.

How are the work breakdown structure and change control connected?

What are the likely outcomes if a change control process is not used? Why?

What are the major differences between managing negative risks and managing positive risks (opportunities)?

page 239

SNAPSHOT  FROM PRACTICE

FROM PRACTICE

Discussion Questions

7.1 Giant Popsicle Gone Wrong

Does this example support the risk event graph (Figure 7.1)? Explain.

7.2 Terminal 5—London Heathrow Airport

Why do you think British Airways decided to go fully operational on day 1?

How could an RBS like the one featured in Figure 7.3 have prevented the disaster from occurring?

7.3 From Dome to Dust

What do you think was the greatest risk facing this project?

How did Controlled Demolition Inc. respond to the risk?

7.4 Risk Management at the Top of the World

How important is it for climbers to join their Sherpas in puja rituals?

Why do climbers not turn back at the designated turnaround time?

Exercises

Gather a small team of students. Think of a project most students would understand; the kinds of tasks involved should also be familiar. Identify and assess major and minor risks inherent in the project. Decide on a response type. Develop a contingency plan for two to four identified risks. Estimate costs. Assign contingency reserves. How much reserve would your team estimate for the whole project? Justify your choices and estimates.

You have been assigned to a project risk team of five members. Because this is the first time your organization has formally set up a risk team for a project, it is hoped that your team will develop a process that can be used on all future projects. Your first team meeting is next Monday morning. Each team member has been asked to prepare for the meeting by developing, in as much detail as possible, an outline that describes how you believe the team should proceed in handling project risks. Each of the team members will hand out his or her proposed outline at the beginning of the meeting. Your outline should include but not be limited to the following information:

Team objectives.

Process for handling risk events.

Team activities.

Team outputs.

Search the Web using the key words “best practices, project management.” What did you find? How might this information be useful to a project manager?

References

Atkinson, W., “Beyond the Basics,” PM Network, May 2003, pp. 38–43.

Avery, G. Project Management, Denial and the Death Zone (Plantation, FL: J. Ross Publishing, 2016).

Baker, B., and R. Menon, “Politics and Project Performance: The Fourth Dimension of Project Management,” PM Network, November 1995, pp. 16–21.

page 240

Browning, T., and R. V. Ramasesh, “Reducing Unwelcome Surprises in Project Management,” Sloan Management Review, Spring 2015, pp. 53–62.

Carr, M. J., S. L. Konda, I. Monarch, F. C. Ulrich, and C. F. Walker, “Taxonomy-Based Risk Identification,” Technical Report CMU/SEI-93-TR 6, Software Engineering Institute, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, 1993.

Ford, E. C., J. Duncan, A. G. Bedeian, P. M. Ginter, M. D. Rousculp, and A. M. Adams, “Mitigating Risks, Visible Hands, Inevitable Disasters, and Soft Variables: Management Research That Matters to Managers,” Academy of Management Executive, vol. 19, no. 4 (November 2005), pp. 24–38.

Gray, C. F., and R. Reinman, “PERT Simulation: A Dynamic Approach to the PERT Technique,” Journal of Systems Management, March 1969, pp. 18–23.

Hamburger, D. H., “The Project Manager: Risk Taker and Contingency Planner,” Project Management Journal, vol. 21, no. 4 (1990), pp. 11–16.

Hillson, D., “Risk Escalation,” project management.com, November 1, 2016. Accessed 9/20/18.

Hulett, D. T., “Project Schedule Risk Assessment,” Project Management Journal, vol. 26, no. 1 (1995), pp. 21–31.

Meyer, A. D., C. H. Loch, and M. T. Pich, “Managing Project Uncertainty: From Variation to Chaos,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Winter 2002, pp. 60–67.

Orlando Sentinel, “Math Mistake Proved Fatal to Mars Orbiter,” November 23, 1999.

Pavlik, A., “Project Troubleshooting: Tiger Teams for Reactive Risk Management,” Project Management Journal, vol. 35, no. 4 (December 2004), pp. 5–14.

Pinto, J. K., Project Management: Achieving Competitive Advantage (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2007).

Project Management Body of Knowledge (Newton Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2017).

Schuler, J. R., “Decision Analysis in Projects: Monte Carlo Simulation,” PM Network, January 1994, pp. 30–36.

Skelton, T., and H. Thamhain, “Managing Risk in New Product Development Projects: Beyond Analytical Methods,” Project Perspectives, vol. 27, no. 1 (2006), pp. 12–20.

Skelton, T., and H. Thamhain, “Success Factors for Effective R&D Risk Management,” International Journal of Technology Intelligence and Planning, vol. 3, no. 4 (2007), pp. 376–386.

Smith, P. G., and D. G. Reinertsen, Developing Products in Half the Time (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1995).

Snizek, J. A., and R. A. Henry, “Accuracy and Confidence in Group Judgment,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, vol. 4, no. 3 (1989), pp. 1–28.

Thamhain, H., “Managing Risks in Complex Projects,” Project Management Journal, vol. 44, no. 20 (2013), pp. 20–35.

page 241

Case 7.1

Alaska Fly-Fishing Expedition*

You are sitting around the fire at a lodge in Dillingham, Alaska, discussing a fishing expedition you are planning with your colleagues at Great Alaska Adventures (GAA). Earlier in the day you received a fax from the president of BlueNote, Inc. The president wants to reward her top management team by taking them on an all-expense-paid fly-fishing adventure in Alaska. She would like GAA to organize and lead the expedition.

You have just finished a preliminary scope statement for the project (which follows). You are now brainstorming potential risks associated with the project.

Brainstorm potential risks associated with this project. Try to come up with at least five different risks.

Use a risk assessment form similar to Figure 7.6 to analyze identified risks.

Develop a risk response matrix similar to Figure 7.8 to outline how you would deal with each of the risks.

PROJECT SCOPE STATEMENT

PROJECT OBJECTIVE

To organize and lead a five-day fly-fishing expedition down the Tikchik River system in Alaska from June 21 to 25 at a cost not to exceed $45,000.

DELIVERABLES

Provide air transportation from Dillingham, Alaska, to Base I and from Base II back to Dillingham.

Provide river transportation consisting of two eight-person drift boats with outboard motors.

Provide three meals a day for the five days spent on the river.

Provide four hours of fly-fishing instruction.

Provide overnight accommodations at the Dillingham lodge plus three four-person tents with cots, bedding, and lanterns.

Provide four experienced river guides who are also fly fishermen.

Provide fishing licenses for all guests.

MILESTONES

Contract signed January 22.

Guests arrive in Dillingham June 20.

Depart by plane to Base Camp I June 21.

Depart by plane from Base Camp II to Dillingham June 25.

page 242

TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS

Fly-in air transportation to and from base camps.

Boat transportation within the Tikchik River system.

Digital cellular communication devices.

Camps and fishing conforming to state of Alaska requirements.

LIMITS AND EXCLUSIONS

Guests are responsible for travel arrangements to and from Dillingham, Alaska.

Guests are responsible for their own fly-fishing equipment and clothing.

Local air transportation to and from base camps will be outsourced.

Tour guides are not responsible for the number of king salmon caught by guests.

ACCEPTANCE CRITERIA

The president of BlueNote, Inc. reviews.

*This case was prepared with the assistance of Stuart Morigeau.

Case 7.2

Silver Fiddle Construction

You are the president of Silver Fiddle Construction (SFC), which specializes in building high-quality, customized homes in the Grand Junction, Colorado, area. You have just been hired by the Czopeks to build their dream home. You operate as a general contractor and employ only a part-time bookkeeper. You subcontract work to local trade professionals. Housing construction in Grand Junction is booming. You are tentatively scheduled to complete 11 houses this year. You have promised the Czopeks that the final costs will range from $450,000 to $500,000 and that it will take five months to complete the house once groundbreaking has begun. The Czopeks are willing to have the project delayed in order to save costs.

You have just finished a preliminary scope statement for the project (which follows). You are now brainstorming potential risks associated with the project.

Identify potential risks associated with this project. Try to come up with at least five different risks.

Use a risk assessment form similar to Figure 7.6 to analyze identified risks.

Develop a risk response matrix similar to Figure 7.8 to outline how you would deal with each of the risks.

PROJECT SCOPE STATEMENT

PROJECT OBJECTIVE

To construct a high-quality, custom home within five months at a cost not to exceed $500,000.

DELIVERABLES

A 2,500-square-foot, 2½-bath, 3-bedroom, finished home.

A finished garage, insulated and sheetrocked.

page 243 Kitchen appliances to include range, oven, microwave, and dishwasher.

A high-efficiency gas furnace with programmable thermostat.

MILESTONES

Permits approved July 5.

Foundation poured July 12.

“Dry in”—framing, sheathing, plumbing, electrical, and mechanical inspections—passed September 25.

Final inspection November 7.

TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS

Home must meet local building codes.

All windows and doors must pass NFRC class 40 energy ratings.

Exterior wall insulation must meet an “R” factor of 21.

Ceiling insulation must meet an “R” factor of 38.

Floor insulation must meet an “R” factor of 25.

Garage will accommodate two cars and one 28-foot-long Winnebago.

Structure must pass seismic stability codes.

LIMITS AND EXCLUSIONS

Home will be built to the specifications and design of the original blueprints provided by the customer.

Owner is responsible for landscaping.

Refrigerator is not included among kitchen appliances.

Air conditioning is not included, but house is prewired for it.

SFC reserves the right to contract out services.

ACCEPTANCE CRITERIA

“Bolo” and Izabella Czopek reviews.

Case 7.3

Trans LAN Project

Trans Systems is a small information systems consulting firm located in Meridian, Louisiana. Trans has just been hired to design and install a local area network (LAN) for the city of Meridian’s social welfare agency. You are the manager for the project, which includes one Trans professional and two interns from a local university. You have just finished a preliminary scope statement for the project (which follows). You are now brainstorming potential risks associated with the project.

Identify potential risks associated with this project. Try to come up with at least five different risks.

Use a risk assessment form similar to Figure 7.6 to analyze identified risks.

Develop a risk response matrix similar to Figure 7.8 to outline how you would deal with each of the risks.

page 244

PROJECT SCOPE STATEMENT

PROJECT OBJECTIVE

To design and install a new local area network (LAN) within one month with a budget not to exceed $125,000 for the Meridian Social Service Agency with minimum disruption to ongoing operations.

DELIVERABLES

Twenty workstations and 20 laptop computers.

Two servers with quad-core processors.

Print server with two color laser printers.

Barracuda Firewall.

Windows R2 server and workstation operating system (Windows 11).

Migration of existing databases and programs to new system.

Four hours of introduction training for client’s personnel.

Sixteen hours of training for client network administrator.

Fully operational LAN system.

MILESTONES

Hardware January 22.

Setting users’ priority and authorization January 26.

In-house whole network test completed February 1.

Client site test completed February 2.

Training completed February 16.

TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS

Workstations with 17-inch flat panel monitors, dual-core processors, 8 GB RAM, 8X DVD+RW, wireless card, Ethernet card, 500 GB SSD.

Laptops with 12-inch display monitor, dual-core processors, 4 GB RAM, wireless card, Ethernet card, 500 GB SSD, and weight less than 4½ lbs.

Wireless network interface cards and Ethernet connections.

System must support Windows 11 platforms.

System must provide secure external access for field workers.

LIMITS AND EXCLUSIONS

On-site work to be done after 8:00 p.m. and before 7:00 a.m. Monday through Saturday.

System maintenance and repair only up to one month after final inspection.

Warranties transferred to client.

Only responsible for installing software designated by the client two weeks before the start of the project.

Client will be billed for additional training beyond that prescribed in the contract.

ACCEPTANCE CRITERIA

Director of the city of Meridian’s Social Service Agency reviews.

page 245

Case 7.4

XSU Spring Concert

You are a member of the X State University (XSU) student body entertainment committee. Your committee has agreed to sponsor a spring concert. The motive behind this concert is to offer a safe alternative to Hasta Weekend. Hasta Weekend is a spring event in which students from XSU rent houseboats and engage in heavy partying. Traditionally this occurs during the last weekend in May. Unfortunately, the partying has a long history of getting out of hand, sometimes leading to fatal accidents. After one such tragedy last spring, your committee wants to offer an alternative experience for those who are eager to celebrate the change in weather and the pending end of the school year.

You have just finished a preliminary scope statement for the project (which follows). You are now brainstorming potential risks associated with the project.

Identify potential risks associated with this project. Try to come up with at least five different risks.

Use a risk assessment form similar to Figure 7.6 to analyze identified risks.

Develop a risk response matrix similar to Figure 7.8 to outline how you would deal with each of the risks.

PROJECT SCOPE STATEMENT

PROJECT OBJECTIVE

To organize and deliver an eight-hour concert at Wahoo Stadium at a cost not to exceed $50,000 on the last Saturday in May.

DELIVERABLES

Local advertising.

Concert security.

Separate beer garden.

Eight hours of music and entertainment.

Food venues.

Souvenir concert T-shirts.

Secure all licenses and approvals.

Secure sponsors.

MILESTONES

Secure all permissions and approvals by January 15.

Sign big-name artist by February 15.

Complete artist roster by April 1.

Secure vendor contracts by April 15.

Setup completed on May 27.

Concert on May 28.

Cleanup completed by May 31.

page 246

TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS

Professional sound stage and system.

At least one big-name artist.

At least seven performing acts.

Restroom facilities for 10,000 people.

Parking available for 1,000 cars.

Compliance with XSU and city requirements/ordinances.

LIMITS AND EXCLUSIONS

Performers are responsible for travel arrangements to and from XSU.

Vendors contribute a set percentage of sales.

Concert must be over by 11:30 p.m.

ACCEPTANCE CRITERIA

The president of XSU student body reviews.

Case 7.5

Sustaining Project Risk Management during Implementation