page 532

CHAPTER

FOURTEEN

14

Project Closure

page 533

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to relive it.

—George Santayana, 1863–1952

Every project comes to an end eventually. But how many project participants get excited about closing out a project? The deliverables are complete. Ownership is ready to be transferred. Everyone’s focus is on what’s next—hopefully a new, exciting project. Carefully managing the closure phase is as important as any other phase of the project. Observation tells us that organizations that manage closure prosper. Those who don’t tend to have projects that drag on forever and repeat the same mistakes over and over.

Closing out a project includes a daunting number of tasks. In the past and on small projects the project manager was responsible for seeing all tasks and loose ends were completed and signed off. This is no longer true. In today’s project-driven organizations that have many projects occurring simultaneously, the responsibility for completing closure tasks has been parsed among the project manager, project teams, project office, contracts office, Human Resources, and others. Many tasks overlap, occur simultaneously, and require coordination and cooperation among these stakeholders.

page 534

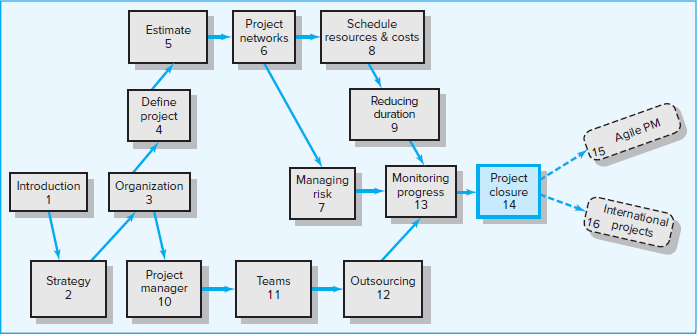

The three major deliverables for project closure are as follows (see Figure 14.1):

Wrapping up the project. The major wrap-up task is to ensure the project is approved and accepted by the customer. Other wrap-up activities include closing accounts, paying bills, reassigning equipment and personnel, finding new opportunities for project staff, closing facilities, and issuing the final report. Checklists are used extensively to ensure tasks are not overlooked. In many organizations, the lion’s share of closure tasks is largely done by the project office in coordination with the project manager. The final report writing is usually assigned to one project office staff member, who assembles input from all stakeholders. In smaller organizations and projects, these closure activities are left to the project manager and team.

Project audit. Audits are post-project reviews of how successful the project was. They include causal analysis and thorough retrospectives that identify lessons learned. These post-project reviews should be held with the team and key stakeholders to catch any missing issues or gaps.

Evaluation of performance and management of the project. Evaluation includes the team, individual team members, and project manager performance. Vendors and the customer may provide external input. Evaluation of the major players provides important information for the future.

FIGURE 14.1

Project Closure and Review Deliverables

This chapter begins with the recognition that projects are shut down for many reasons. Not all projects end with a clear “Finished” and are turned over to a customer. Regardless of the conditions for ending a project, the general process of closure is similar for all projects, though the endings may differ significantly. Wrap-up closure tasks are noted first. These tasks represent all the tasks that must be “cleaned up” before the project is terminated. Project audits and lessons learned are examined next. Finally, evaluation of individual and team performance is discussed.

14.1 Types of Project Closure

On some projects the end may not be as clear as would be hoped. Although the scope statement may define a clear ending for a project, the actual ending may or may not correspond. Fortunately, a majority of projects are blessed with a well-defined ending. Regular project reviews will identify projects having endings different from plans. Following are the types of closure.

Normal. The most common circumstance for project closure is simply a completed project. For many development projects, the end involves handing off the final design to Production and creating a new product or service line. For other internal IT projects, such as system upgrades or the creation of new inventory control systems, page 535the end occurs when the output is incorporated into ongoing operations. Some modifications in scope, cost, and schedule probably occurred during implementation.

Premature. For a few projects, the project may be completed early with some parts of the project eliminated. For example, in a new-product development project, a marketing manager may insist on production models before testing:

“Give the new product to me now, the way it is. Early entry into the market will mean big profits! I know we can sell a bazillion of these. If we don’t do it now, the opportunity is lost!”

The pressure is on to finish the project and send it to Production. Before succumbing to this form of pressure, the implications and risks associated with this decision should be carefully reviewed and assessed by senior management and all stakeholders. Too frequently, the benefits are illusory and dangerous and carry large risks.

Perpetual. Some projects never seem to end. The major characteristic of this kind of project is constant “add-ons,” suggesting a poorly conceived project scope. For example, in 1984 President Ronald Reagan launched the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI). Over 30 years later, many of the technical difficulties with creating a “Star Wars” defense system are still being addressed. Most experts admit they do not have a good idea when such a system would be sufficiently robust to be deployed. At some point the review group should recommend methods for bringing final closure to this type of project or the initiation of another project. For example, adding a new feature to an old project could replace a segment of a project that appears to be perpetual.

Failed project. Failed projects are usually easy to identify and easy for a review group to close down. However, every effort should be made to communicate the technical (or other) reasons for termination of the project; in any event, project participants should not be left with an embarrassing stigma of working on a project that failed. Many projects fail because of circumstances beyond the control of the project team. See Snapshot from Practice 14.1: The Wake for a novel response to a canceled project.

page 536Changed priority. Organizations’ priorities often change and strategies shift directions. For example, during the 2008–2010 financial crisis, organizations shifted their focus from money-making projects to cost-saving projects. The oversight group continually revises project selection priorities to reflect changes in organizational direction. Thus, a project may start with a high priority but see its rank erode or crash during its project life cycle as conditions change. When priorities change, projects in process may need to be altered or canceled.

Different types of project termination present unique issues. Some adjustments to generic closure processes may be necessary to accommodate the type of project termination you face.

14.2 Wrap-up Closure Activities

The major challenges for the project manager and team members are over. Getting the project manager and project participants to wrap up the odds and ends necessary to fully complete a project is often difficult. It’s like the party is over—now who wants to help clean up? Much of the work is mundane and tedious. Motivation can be the chief challenge. For example, accounting for equipment and completing final reports are perceived as dull administrative tasks by project professionals who are action-oriented individuals.

The project manager’s challenge is to keep the project team focused on the remaining project activities and delivery to the customer until the project is complete. Communicating a closure and review plan and schedule early allows the project team to (1) accept the psychological fact the project will end and (2) prepare to move on. The ideal scenario is to have each team member’s next assignment ready when project completion is announced. Project managers need to be careful to maintain their enthusiasm for completing the project and hold people accountable to deadlines, which are prone to slip during the waning stages of the project.

Project closure usually includes the following six major activities.

Getting delivery acceptance from the customer.

Shutting down resources and releasing to new uses.

Reassigning project team members.

Closing accounts and seeing that all bills are paid.

Delivering the project to the customer.

Creating a final report.

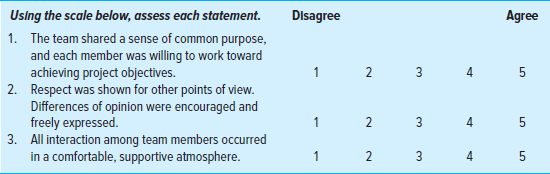

Administering the details of closing out a project can be intimidating. Some organizations have checklists of over 100 wrap-up tasks! These checklists deal with closure details such as facilities, teams, staff, customer, vendors, and the project itself. A partial administrative closure checklist is shown in Table 14.1.

TABLE 14.1

Wrap-up Closure Checklist

| Task | Completed? Yes/No |

|

| Team | ||

| 1 | Has a schedule for reducing project staff been developed and accepted? | |

| 2 | Has staff been released or notified of new assignments? | |

| 3 | Have performance reviews for team members been conducted? | |

| 4 | Has staff been offered outplacement services and career counseling activities? | |

| Vendors/Contractors | ||

| 5 | Have performance reviews for all vendors been conducted? | |

| 6 | Have project accounts been finalized and all billing closed? | |

| Customer/Users | ||

| 7 | Has the customer signed off on the delivered product? | |

| 8 | Have an in-depth project review and evaluation interview with the customer been conducted? | |

| 9 | Have the users been interviewed to assess their satisfaction with the deliverables? With the project team? With vendors? With training? With support? With maintenance? | |

| Equipment and Facilities | ||

| 10 | Have project resources been transferred to other projects? | |

| 11 | Have rental or lease equipment agreements been closed out? | |

| 12 | Has the date for the closure review been set and stakeholders notified? | |

| Attach comments or links on any tasks you feel need explanation. |

Getting delivery acceptance by the customer is a major and critical closure activity. Delivery of some projects to the customer is straightforward. Others are more complex and difficult. Ideally there should be no surprises. This requires a well-defined scope and an effective change management system with active customer involvement. User involvement is critical to acceptance (see Snapshot from Practice 14.2: New Ball Goes Flat in the NBA).

Project managers are not always responsible for all facets of the closeout process. In many organizations, accounts and bills are dealt with by contract offices. Reassignments are managed by the firm’s project management office. Disputes are dealt with by lawyers. Sometimes new managers are brought in to close out the project. page 537They specialize in customer relations and/or attention to detail and are often called “terminators” within their organization.

The conditions for completing and transferring the project should be set before the project begins. A completed software project is a good example of the need to work out the details in advance. If the user has problems using the software, will the customer withhold final payments? Who is responsible for supporting and training the user? If these conditions are not clearly defined up front, getting delivery acceptance can be troublesome.

Another delivery tactic (briefly mentioned in Chapter 7) for a project that has been outsourced is known as build, own, operate, and transfer (BOOT). In this type of project the contractor builds, owns, and operates the project deliverable for a set period of time. For example, Haliburton will operate a hydroelectric plant for six months before turning over operations to their Indian counterparts. During this time all the bugs are worked out and conditions for delivery are satisfied. Again, the delivery conditions need to be carefully set up before the project begins; if not, wrap-up activities can develop a life of their own.

Releasing the project team typically occurs gradually during the closure phase. For some people, termination of their responsible activities ends before the project is delivered to the customer or user. Reassignment for these participants needs to take place well before the final finish date. For the remaining team members (full or part time), termination may result in a new project or a return to their functional job. Sometimes, on product development efforts, team members are assigned to operations positions and play an active role in the production of the new product. For contract people it may mean the end of their assignment to that project; in some cases there may be page 538follow-up work or user support possibilities. A small number of part-time participants may be recommended to the user organization to train users or operate new equipment or systems.

Since many work invoices are not submitted until after the project is officially over, closing out contracts is often messy and filled with untied ends. For example, it is improbable that all invoices have been finalized, billed, and paid. Further, when page 539contractors are used, there is a need to verify that all the contracted work has been done. Keeping contract records, such as progress reports, invoices, change records, and payment records, is important, should a compliance or lawsuit occur. Too often in the haste to meet deadlines, paperwork and recordkeeping get short-changed, only to create major headaches when it comes time for final documentation.

There are many more wrap-up activities; it is important to complete all of them. Experience has proved time and again that not doing all the little cleanup tasks well will create problems later. Appendix 14.1 presents an example of a closeout checklist used by the state of Virginia.

A final wrap-up activity is some form of celebration. For successful projects, an upbeat, festive celebration brings closure to the enjoyable experiences everyone has had and the need to say good-bye. Celebration is an opportunity to recognize the effort project stakeholders contributed. Even if the project did not reach its objectives, recognize the effort involved and goals that were achieved. If the project was a success, invite everyone who in some way contributed to project success. Thank the team and each one individually. The spirit of the celebration should be one in which stakeholders are thanked for a job well done and leave with a good feeling of accomplishment.

14.3 Project Audits

Project audits are more than the status reports suggested in Chapter 13, which report on project performance. Project audits do use performance measures and forecast data. But project audits are more inclusive. Project audits not only examine project success but also review why the project was selected. Project audits include a reassessment of the project’s role in the organization’s priorities. Project audits include a check on the organizational culture to ensure it facilitates the type of project being implemented. They assess if the project team is functioning well and is appropriately staffed. Audits make recommendations and articulate lessons learned.

Project audits can be performed while a project is in process and after a project is completed. There are only two minor differences between these audits:

In-process project audits. Project audits early in projects allow for corrective changes, if they are needed, on the audited project or others in progress. In-process project audits concentrate on project progress and performance and check if conditions have changed. For example, have priorities changed? Is the project mission still relevant? In some cases, the audit report may recommend shutting down the project or significantly changing the scope of the project.

Post-project audits. These audits tend to include more detail and depth than in-process project audits. Project audits of completed projects emphasize improving the management of future projects. These audits are more long-term oriented than in-process audits. Post-project audits do check on project performance, but the audit represents a broader view of the project’s role in the organization; for example, were the strategic benefits claimed actually delivered?

The depth and detail of the project audit depend on many factors. Some are listed in Table 14.1. Because audits cost time and money, they should include no more time or resources than are necessary and sufficient. Early in-process project audits tend to be perfunctory unless serious problems or concerns are identified. Then, of course, the audit would be carried out in more detail. Because in-process project audits can be worrisome and destructive to the project team, care must be taken to protect project team morale. The audit should be carried out quickly, and the report should be as page 540positive and constructive as possible. Post-project audits are more detailed and inclusive and contain more project team input.

In summary, plan the audit and limit the time for the audit. For example, in post-project audits, for all but very large projects, a one-week limit is a good benchmark. Beyond this time, the marginal return of additional information diminishes quickly. Small projects may require only one or two days and one or two people to conduct an audit.

The priority team functions well in selecting projects and monitoring performance—cost and time. However, reviewing and evaluating projects and the process of managing projects are usually delegated to independent audit groups. Each audit group is charged with evaluating and reviewing all factors relevant to the project and to managing future projects. The outcome of the project audit is a report.

The Project Audit Process

The following guidelines, which should be noted before conducting a project audit, will improve your chances for a successful audit.

First and foremost, the philosophy must be that the project audit is not a witch hunt.

Comments about individuals or groups participating in the project should be minimized. Keep to project issues, not what happened or who did what.

Audit activities should be intensely sensitive to human emotions and reactions. The inherent threat to those being evaluated should be reduced as much as possible.

The accuracy of data should be verifiable or noted as subjective, judgmental, or hearsay.

Senior management should announce support for the project audit and see that the audit group has access to all information, project participants, and (in most cases) project customers.

The attitude toward a project audit and its aftermath depends on the modus operandi of the audit leadership and group. The objective is not to prosecute. The objective is to learn and conserve valuable organizational resources where mistakes have been made. Friendliness, empathy, and objectivity encourage cooperation and reduce anxiety.

The audit should be completed as quickly as is reasonable.

With these guidelines in mind, the project audit process is conveniently divided into three steps: initiation and staffing, data collection and analysis, and reporting. Each step is briefly discussed next.

Step 1: Initiation and Staffing

Initiation of the audit process depends primarily on organization size and project size, along with other factors. In small organizations and projects where face-to-face contact at all levels is prevalent, an audit may be informal and represent only another staff meeting. But even in these environments the content of a formal project audit should be examined and covered, with notes made of the lessons learned. In medium-sized organizations with few projects the audit is likely to be conducted by someone from management with project management experience. In large companies or organizations with many projects the audit is under the purview of the project office.

A major tenet of the project audit is that the outcome must represent an independent, outside view of the project. Maintaining independence and an objective view is difficult, given that project stakeholders frequently view audits as negative. Careers and reputations can be tarnished, even in organizations that tolerate mistakes. In less page 541forgiving organizations, mistakes can lead to termination or exile to less significant regions of an organization. Of course, if the result of an audit is favorable, careers and reputations can be enhanced. Given that project audits are susceptible to internal politics, some organizations rely on outside consulting firms to conduct the audits.

Step 2: Data Collection and Analysis

Each organization and project is unique. Therefore, the specific kinds of information that will be collected depend upon the industry, project size, newness of technology, and project experience. These factors can influence the nature of the audit. However, information and data are gathered to answer questions similar to the following.

Organization View

Was the organizational culture supportive and correct for this type of project? Why? Why not?

Was senior management’s support adequate?

Did the project accomplish its intended purpose?

Were the risks for the project appropriately identified and assessed? Were contingency plans used? Were they realistic? Have risk events occurred that have an impact greater than anticipated?

Were the right people and talents assigned to this project?

What does evaluation from outside contractors suggest?

Were the project start-up and hand-off successful? Why? Is the customer satisfied?

Project Team View

Were the project planning and control systems appropriate for this type of project? Should all projects of a similar size and type use these systems? Why or why not?

Did the project conform to plan? Is the project over or under budget and schedule? Why?

Were interfaces and communications with project stakeholders adequate and effective?

Did the team have adequate access to organizational resources—people, budget, support groups, equipment? Were there resource conflicts with other ongoing projects?

Was the team managed well? Were problems confronted, not avoided?

The audit group should not be limited to these questions but rather should include other questions related to their organization and project type—for example, research and development, marketing, information systems, construction, or facilities. The preceding generic questions, although overlapping, represent a good starting point and will go a long way toward identifying project problem and success patterns.

Step 3: Reporting

The major goal of the audit report is to improve the way future projects are managed. Succinctly, the report attempts to capture needed changes and lessons learned from a current or finished project. The report serves as a training instrument for project managers of future projects.

Audit reports need to be tailored to the specific project and organizational environment. Nevertheless, a generic format for all audits facilitates the development of page 542an audit database and a common outline for those who prepare audit reports and the managers who read and act on their content. A very general outline common to those found in practice is as follows:

1. Classification. The classification of projects by characteristics allows prospective readers and project managers to be selective in the use of the report content. Typical classification categories include the following:

Project type—e.g., development, marketing, systems, construction.

Size—monetary.

Number of staff.

Technology level—low, medium, high, new.

Strategic or support.

Other classifications relevant to the organization should be included.

2. Analysis. The analysis section includes succinct, factual review statements of the project (PMBOK, 2017)—for example,

Scope objectives, the criteria used to evaluate scope and evidence that the completion criteria were met.

Quality objectives, the criteria used to assess the project and product/service quality, and reasons for variances.

Cost objectives, including acceptable cost range, actual costs, and reasons for any variances.

Schedule objectives, including verification of milestone completion dates, and reasons for variances.

Summary of risks and issues encountered on the project and how they were addressed.

Outcomes achieved, including an assessment of how the final product, service, or result addressed the business need identified in the selection process.

3. Recommendations. Usually audit recommendations represent major corrective actions that should take place. Audit recommendations are often technical and focus on solutions to problems that surfaced. For example, to avoid rework, the report of a construction project recommended shifting to a more resilient building material. In other cases, recommendations may include terminating or sustaining vendor or contractor relationships.

4. Lessons learned. These do not have to be in the form of recommendations. Lessons learned serve as reminders of mistakes easily avoided and actions easily taken to ensure success. In practice, new project teams reviewing audits of past projects similar to the one they are about to start have found audit reports very useful. Team members will frequently remark later, “The recommendations were good, but the ‘lessons learned’ section really helped us avoid many pitfalls and made our project implementation smoother.” It is precisely for this reason that lessons learned in the form of project retrospectives have taken on greater prominence and warrant further discussion. See Snapshot from Practice 14.3: Operation Eagle Claw.

5. Appendix. The appendix may include backup data or details of analysis that allow others to follow up if they wish. It should not be a dumping ground used for filler; only critical, pertinent information should be attached.

page 543

Project Retrospectives

The term retrospective has emerged to denote specific efforts at identifying lessons learned on projects. Proponents believe that the traditional audit process focuses too much on project success and evaluation, which interferes with the surfacing and transferal of important lessons learned. They advocate a separate effort toward capturing lessons learned. In many ways this effort mirrors the auditing process. Typically an page 544independent, trained facilitator acts as a guide who leads the project team through an analysis of project activities that went well and what needed improvement, as well as the development of a follow-up action plan with goals and accountability. This facilitator may come from the project office or be an external consultant. Wherever this individual comes from, it is critical that she be perceived as independent and unbiased.

In retrospective methodology, the facilitator uses several questionnaires to conduct post-project audits. These surveys focus not only on project operations but also on how the organization’s culture impacted project success and failures. Table 14.2 provides a sampling of the former, while Table 14.3 provides a sample of the latter.

TABLE 14.2

Project Process Review Questionnaire

| Item | Comments | |

| 1. | Were the project objectives and strategic intent of the project clearly and explicitly communicated? | |

| 2. | Were the objectives and strategy in alignment? | |

| 3. | Were the stakeholders identified and included in the planning? | |

| 4. | Were project resources adequate for this project? | |

| 5. | Were people with the right skill sets assigned to this project? | |

| 6. | Were time estimates reasonable and achievable? | |

| 7. | Were the risks for the project appropriately identified and assessed before the project started? | |

| 8. | Were the processes and practices appropriate for this type of project? Should projects of similar size and type use these systems? Why/why not? | |

| 9. | Did outside contractors perform as expected? Explain. | |

| 10. | Were communication methods appropriate and adequate among all stakeholders? Explain. | |

| 11. | Is the customer satisfied with the project product? | |

| 12. | Are the customers using the project deliverables as intended? Are they satisfied? | |

| 13. | Were the project objectives met? | |

| 14. | Are the stakeholders satisfied their strategic intents have been met? | |

| 15. | Has the customer or sponsor accepted a formal statement that the terms of the project charter and scope have been met? | |

| 16. | Were schedule, budget, and scope standards met? | |

| 17. | Is there any one important area that needs to be reviewed and improved upon? Can you identify the cause? |

TABLE 14.3

Organizational Culture Review Questionnaire

| Item | Comments | |

| 1. | Was the organizational culture supportive for this type of project? | |

| 2. | Was senior management support adequate? | |

| 3. | Were people with the right skills assigned to this project? | |

| 4. | Did the project office help or hinder management of the project? Explain. | |

| 5. | Did the team have access to organizational resources (people, funds, equipment)? | |

| 6. | Was training for this project adequate? Explain. | |

| 7. | Were lessons learned from earlier projects useful? Why? Where? | |

| 8. | Did the project have a clear link to organizational objectives? Explain. | |

| 9. | Was project staff properly reassigned? | |

| 10. | Was the Human Resources Office helpful in finding new assignments? Comment. |

With survey information in hand, the facilitator visits one-on-one with project team members, the project manager, and other stakeholders to dive deeper into cause-effect impacts. For example, the facilitator may discover that one of the primary reasons for a lack of timely decision making and poor coordination between groups was that team members were bombarded with too much information and had a difficult time sorting through what was critical and what could be ignored.

Armed with the information gleaned from one-on-one sessions and other sources, the facilitator leads a team retrospective session. The session first reviews the facilitator’s report and attempts to add key information. So, with regard to the information overload problem, team members identify not only failure to flag critical information page 545but also a tendency to “cc” everyone, just in case. The facilitator works with the team to develop a system that not only prioritizes information but also does so according to who needs to receive it.

Each lesson is assigned an owner, typically a team member who is very interested in and familiar with the lesson. This team member/owner will serve as a contact point for anyone needing information (expertise, contacts, templates, etc.) relating to the lesson. This person often reports lessons learned to larger audiences within their organization that would benefit from the collective wisdom.

Not only is there a contact person but also lessons learned need to be documented and archived in a manner that makes them accessible to and usable by others. Many organizations have created lessons learned repositories that store historical information. These repositories use sophisticated search engines that permit others to quickly sort through and access lessons specific to their needs. Failure to do so will produce a system that is undervalued and underutilized.

14.4 Project Audits: The Big Picture

Individual audits or post-project retrospectives can yield valuable lessons and recommendations that team members can apply to future project work. When done on a consistent basis, they can lead to significant improvements in the processes and techniques that organizations use to complete projects. A more encompassing look from an organizationwide point of view is to use a project maturity model. The purposes of all maturity models (and there are many available) are to enable organizations to assess their progress in implementing the best practices in their industry and move to improvement. It is important to understand that the model does not ensure success; it only serves as a measuring stick and an indicator of progress.

The term maturity model was coined in the late 1980s from a research study by the United States government and the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) at Carnegie Mellon University. The government wanted a tool to predict successful software development by contractors. The eventual outcome of this research was the Capability page 546Maturity Model Integration (CMMI). The model focuses on guiding and assessing organizations in implementing concrete best practices in managing software development projects. Since its development, the model is now used across all industries. Currently, over 2,400 organizations around the world report their maturity progress to the Software Engineering Institute. (See website at www.sei.cmu.edu/activities/sema/profile.html.)

One newer model has received a great deal of publicity. In January 2004, after eight years of development, the Project Management Institute rolled out its second version of the Organizational Project Maturity Model. The latest version is called OPM3TM. Typically these models are divided into a continuum of growth levels: Initial, Repeatable, Defined, Managed, and Optimized. Figure 14.2 presents one version that borrows liberally from other models, focusing less on a process and more on the state an organization has evolved to in managing projects.

FIGURE 14.2

Project Management Maturity Model

Level 1: Ad Hoc Project Management

No consistent project management process is in place. How a project is managed depends upon the individuals involved. Characteristics of this level include

No formal project selection system exists—projects are done because people decide to do them or because a high-ranking manager orders it done.

How any one project is managed varies by individual—unpredictability.

No investment in project management training is made.

Working on projects is a struggle because it goes against the grain of established policies and procedures.

Level 2: Formal Application of Project Management

The organization applies established project management procedures and techniques. This level is often marked by tension between project managers and line managers, who need to redefine their roles. Features of this level include

Standard approaches to managing projects, including scope statements, WBS, and activity lists, are used.

page 547Quality emphasis is on the product or outcome of the project and is inspected instead of built in.

The organization is moving in the direction of stronger matrix with project managers and line managers working out their respective roles.

Growing recognition of need for cost control, not just scope and time management, exists.

There is no formal project priority system established.

Limited training in project management is provided.

Level 3: Institutionalization of Project Management

An organizationwide project management system, tailored to specific needs of the organization with the flexibility to adapt the process to unique characteristics of the project, is established. Characteristics of this level include

An established process for managing projects is evident by planning templates, status report systems, and checklists for each stage of the project life cycle.

Formal criteria are used to select projects.

Project management is integrated with quality management and concurrent engineering.

Project teams try to build in quality, not simply inspect it.

The organization is moving toward a team-based reward system to recognize project execution.

Risk assessment derived from WBS and technical analyses and customer input is in place.

The organization offers expanded training in project management.

Time-phased budgets are used to measure and monitor performance based on earned value analysis.

A specific change control system for requirements, cost, and schedule is developed for each project, and a work authorization system is in place.

Project audits tend to be performed only when a project fails.

Level 4: Management of Project Management System

The organization develops a system for managing multiple projects that are aligned with the strategic goals of the organization. Characteristics of this level include

Portfolio project management is practiced; projects are selected based on resource capacity and contribution to strategic goals.

A project priority system is established.

Project work is integrated with ongoing operations.

Quality improvement initiatives are designed to improve both the quality of the project management process and the quality of specific products and services.

Benchmarking is used to identify opportunities for improvement.

The organization has established a project management office or center for excellence.

Project audits are performed on all significant projects; lessons learned are recorded and used on subsequent projects.

An integrative information system is established for tracking resource usage and performance of all significant projects.

page 548

Level 5: Optimization of Project Management System

The focus is on continuous improvement through incremental advancements of existing practices and by innovations using new technologies and methods. Features include

A project management information system is fine-tuned; specific and aggregate information is provided to different stakeholders.

An informal culture that values improvement drives the organization, not policies and procedures.

There is greater flexibility in adapting the project management process to demands of a specific project.

A major theme of this book is that the culture of the organization has a profound impact on how project management methodology operates. Audits and performance evaluation require informed judgment. Good decision making depends not only on the accuracy of the information but also on the right information. For example, imagine how much different your response could be if you made an honest mistake but did not trust management and felt insecure versus if you had confidence and trust in management. Or think how different the quality of the information that would surface from a team would be where trust was divided versus a team that works in a Level 5 environment.

Progress from one level to the next will not occur overnight. The Software Engineering Institute estimates the following median times for movement:

Maturity level 1 to 2 is 22 months.

Maturity level 2 to 3 is 19 months.

Maturity level 3 to 4 is 25 months.

Maturity level 4 to 5 is 13 months.

Why does it take so long? One reason is simply organizational inertia. It is difficult for complex social organizations to institute significant changes while maintaining business efficacy: “How do we find time to change when we are so busy just keeping our heads above water?”

A second significant reason is that one cannot leapfrog past any one level. Just as a child cannot avoid the trials and tribulations of being a teenager by adopting all the lessons learned by his parents, people within the organization have to work through the unique challenges and problems of each level to get to the next level. Learning of this magnitude naturally takes time and cannot be avoided by using quick fixes or simple remedies. See Snapshot from Practice 14.4: 2015 PMO of the Year for how a PMO improved the maturity of project management operations at a large credit union.

14.5 Post-implementation Evaluation

The purpose of project evaluation is to assess how well the project team, team members, and project manager performed.

Team Evaluation

Evaluation of performance is essential to encourage changes in behavior and to support individual career development. Evaluation implies measurement against specific criteria. Experience corroborates that before commencement of a project, the stage must be set so expectations, standards, supportive organizational culture, and constraints are in place; if not, the effectiveness of the evaluation process will suffer.

page 549

Evaluation of project team performance tends to be based on achieving project objectives according to time, cost, and specifications (scope). It has become more common to add customer/end user satisfaction to the assessment. After all, many argue that the most important indicator of project success is customer satisfaction.

Less common is assessing how well the team worked together and with others. Remember, projects are socio-technical endeavors and the human dimension should be evaluated along with the technical dimension. Take, for example, a project that was a technical success but emotions and tempers flared toward the end, leaving people swearing they would never work with each other again. Or consider a successful project in which over half of the team was so burned out by the long hours and stress they eventually left the company. Another example is an unsuccessful project on which, on closer examination, the team should be applauded for achieving what they did, given the hurdles they faced. Important knowledge can be obtained by looking at the underlying behavioral dynamics of a project.

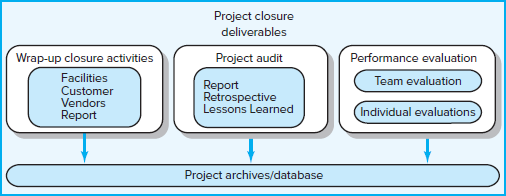

In practice, the team evaluation process takes many forms—especially when evaluation goes beyond time, budget, and specifications. The typical mechanism for evaluating teams is a survey administered by a consultant, a staff member from the Human Resources Department, or e-mail. The survey is normally restricted to team members, but in some cases, other project stakeholders interacting with the team are included in the survey. An example of a partial survey is found in Table 14.4. After the results are tabulated, the team meets with the facilitator and/or senior management, and the results are reviewed.

TABLE 14.4

Sample Team Evaluation and Feedback Survey

|

This session is comparable to the team-building sessions described in Chapter 11, except that the focus is on using the survey results to assess the development of the page 550team, its strengths and weaknesses, and the lessons that can be applied to future project work. The results of team evaluation surveys are helpful in changing behavior to better support team communication, the team approach, and continuous improvement of team performance.

Individual, Team Member, and Project Manager Performance Reviews

Organizations vary in the extent to which their project managers are actively involved in the appraisal process of team members. In organizations where projects are managed within a functional organization, the team member’s area manager, not the project manager, is responsible for assessing performance. The area manager may solicit the project manager’s opinion of the individual’s performance on a specific project; this will be factored into the individual’s overall performance. In a balanced matrix, the project manager and the area manager jointly evaluate an individual’s performance. In project matrix and project organizations in which the lion’s share of the individual’s work is project related, the project manager is responsible for appraising individual performance. One process that appears to be gaining wider acceptance is the multi-rater appraisal, or “360-degree feedback,” which involves soliciting feedback concerning team members’ performance from all the people their work affects. This would include not only project and area managers but also peers, subordinates, and even customers. See Snapshot from Practice 14.5: The 360-Degree Feedback.

Performance appraisals generally fulfill two important functions. The first is developmental: the focus is on identifying individual strengths and weaknesses and developing action plans for improving performance. The second is evaluative and involves assessing how well a person has performed in order to determine salary or merit adjustments. These two functions are not compatible. Employees, in their eagerness to find out how much pay they will receive, tend to tune out constructive feedback on how they can improve their performance. Likewise, managers tend to be more concerned with justifying their decision than engaging in a meaningful discussion on how employees can improve their performance. It is difficult to be both a coach and a judge. As a result, several experts on performance appraisal systems recommend that organizations separate performance reviews, which focus on individual improvement, from pay reviews, which allocate the distribution of rewards (cf., Latham & Wexley, 1993; Romanoff, 1989).

In some matrix organizations, project managers conduct the performance reviews, while area managers are responsible for pay reviews. In other cases, performance reviews are part of the project closure process, and pay reviews are the primary objective of the annual performance appraisal. Other organizations avoid this dilemma by allocating only group rewards for project work and providing annual awards for page 551individual performance. The remaining discussion is directed at reviews designed to improve performance because pay reviews are often outside the jurisdiction of the project manager.

Individual Reviews

Organizations employ a wide range of methods to review individual performance on a project. In general, review methods of individual performance center on the technical and social skills brought to the project and team. Some organizations rely simply on an informal discussion between the project manager and the project member. Other organizations require project managers to submit written evaluations that describe and assess an individual’s performance on a project. Many organizations use rating scales similar to the team evaluation survey in which the project manager rates the individual according to a certain scale (e.g., from 1 to 5) on a number of relevant performance dimensions (e.g., teamwork, customer relations). Some organizations augment these rating schemes with behaviorally anchored descriptions of what constitutes a 1 rating, a 2 rating, and so forth. Each method has its strengths and weaknesses, and, unfortunately, in many organizations the appraisal systems were designed to support mainstream operations and not unique project work. The bottom line is that project managers have to use as best they can the performance review system mandated by their organization.

page 552

Regardless of the method, the project manager needs to meet with each team member and discuss her performance. Following are some general tips for conducting performance reviews.

Always begin the process by asking the individual to evaluate his contributions to the project. First, this approach may yield valuable information that you were not aware of. Second, the approach may provide an early warning for situations in which there is disparity in assessments. Finally, this method reduces the judgmental nature of the discussion.

Avoid, when possible, drawing comparisons with other team members; rather, assess the individual in terms of established standards and expectations. Comparisons tend to undermine cohesion and divert attention away from what the individual needs to do to improve performance.

When you have to be critical, focus the criticism on specific examples of behavior rather than on the individual personally. Describe in specific terms how the behavior affected the project.

Be consistent and fair in your treatment of all team members. Nothing breeds resentment more than if, through the grapevine, individuals feel they are being held to a different standard than are other project members.

Treat the review as only one point in an ongoing process. Use it to reach an agreement on how the individual can improve her performance.

Both managers and subordinates may dread a formal performance review. Neither side feels comfortable with the evaluative nature of the discussion and the potential for misunderstanding and hurt feelings. Much of this anxiety can be alleviated if the project manager is doing his job well. Project managers should constantly give team members feedback throughout the project so that individuals can have a pretty good idea how well they have performed and how the manager feels before the formal meeting. Post-project angst can be avoided if pre-project expectations are discussed before the project and regularly reinforced during project performance.

While in many cases the same process that is applied to reviewing the performance of team members is applied to evaluating the project manager, many organizations augment this process, given the importance of the position to their organization. This is where conducting the 360-degree review is becoming more popular. In project-driven organizations, the project office typically is responsible for collecting information on a specific project manager from customers, vendors, team members, peers, and other managers. This approach has tremendous promise for developing more effective project managers.

In addition to performance reviews, data are collected for project retrospectives, which can present situations that may influence performance. In these situations, performance evaluations should recognize and note the unusual situation.

Summary

The goals of project closure are to complete the project and to improve performance in future projects. Implementing closure and review has three major deliverables: wrap-up, audit, and performance evaluation. Wrap-up activities put the project “to bed” and include completing the final project deliverable, closing accounts, finding new opportunities for project staff, closing facilities, and creating the final report. Project audits assess the overall success of the project. Retrospectives are used to identify lessons page 553learned and improve future performance. Individual and team evaluations assess performance and opportunities for improvement. A project should not be considered done until all three activities have been completed. The culture of the organization and the project team will play a major factor in the efficacy of these activities.

Key Terms

Review Questions

How does the project closure review differ from the performance measurement control system discussed in Chapter 13?

What major information would you expect to find in a project audit?

Why is it difficult to perform a truly independent, objective review?

Comment on the following statement: “We cannot afford to terminate the project now. We have already spent more than 50 percent of the project budget.”

Why should an organization be interested in knowing what level they are at in the project maturity model?

Why should you separate performance reviews from pay reviews? How do you do this?

Advocates of retrospective methodology claim there are distinguishing characteristics that increase its value over past lessons learned methods. What are they? How does each characteristic enhance project closure and review?

SNAPSHOT  FROM PRACTICE

FROM PRACTICE

Discussion Questions

14.1 The Wake

What was Sally able to achieve by holding a wake for the canceled project?

14.2 New Ball Goes Flat in the NBA

How did the culture of the NBA affect this project?

What could the NBA have done differently to increase the likelihood of success?

14.3 Operation Eagle Claw

Assume you are to command a similar mission. What are two things you would insist on, based on what you learned about Eagle Claw?

14.4 2015 PMO of the Year: Navy Federal Credit Union

How did the project management system evolve at Navy Federal Credit Union?

14.5 The 360-Degree Feedback

Have you been the subject of a 360-degree review or participated in one? What was it like? How useful was it?

What effect do you think 360-degree reviews have on the culture of an organization?

page 554

Exercises

Consider a course that you recently completed. Perform a review of the course (the course represents a project and the course syllabus represents the project plan).

Imagine you are conducting a review of the International Space Station project. Research press coverage and the Internet to collect information on the current status of the project. What are the successes and failures to date? What forecasts would you make about the completion of the project and why? What recommendations would you make to top management of the program and why?

Interview a project manager who works for an organization that implements multiple projects. Ask the manager what kind of closure procedures are used to complete a project and whether lessons learned are used.

What are some of the lessons learned from a recent project in your organization? Was a retrospective done? What action plans were generated to improve processes as a result of the project?

References

“Annual Survey of Business Improvement Architects,” PM Network, April 2007, p. 18.

Cooke-Davies, T., “Project Management Closeout Management: More Than Simply Saying Good Bye and Moving On,” in J. Knutson (ed.), Project Management for Business Professionals (Indianapolis, IN: John Wiley and Sons, 2001), pp. 200–14.

Fretty, P., “Why Do Projects Really Fail?” PM Network, March 2006, pp. 45–48.

Gobeli, D., and E. W. Larson, “Barriers Affecting Project Success,” in 1986 Proceedings Project Management Institute: Measuring Success (Upper Darby, PA: Project Management Institute, 1986), pp. 22–29.

Kerth, Norman L., Project Retrospectives: A Handbook for Team Reviews (New York: Dorset House, 2001).

Kwak, Y. H., and C. W. Ibbs, “Calculating Project Management’s Return on Investment,” Project Management Journal, vol. 31, no. 2 (March 2000), pp. 38–47.

Ladika, S., “By Focusing on Lessons Learned, Project Managers Can Avoid Repeating the Same Old Mistakes,” PM Network, February 2008, pp. 75–77.

Latham, G. P., and K. N. Wexley, Increasing Productivity through Performance Appraisal, 2nd ed. (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1993).

Lavell, D., and R. Martinelli, “Program and Project Retrospectives: An Introduction,” PM World Today, January 2008, p. 1.

Marlin, M., “Implementing an Effective Lessons Learned Process in a Global Project Environment,” PM World Today, November 2008, pp. 1–6.

Nelson, R. R., “Project Retrospectives: Evaluating Project Success, Failure, and Everything in Between,” MIS Quarterly Executive, vol. 4, no. 3 (September 2005), p. 372.

Pippett, D. D., and J. F. Peters, “Team Building and Project Management: How Are We Doing?” Project Management Journal, vol. 26, no. 4 (December 1995), pp. 29–37.

page 555

Project Management Institute, Organizational Project Management Maturity Model (OPM3), 3rd ed. (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2013).

Project Management Institute, Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK), 6th ed. (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2017).

Romanoff, T. K., “The Ten Commandments of Performance Management,” Personnel, vol. 66, no. 1 (1989), pp. 24–26.

Royer, I., “Why Bad Projects Are So Hard to Kill,” Harvard Business Review, February 2003, pp. 49–56.

Senge, P., The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization (New York: Doubleday, 1990).

Sheperd, D. A., H. Patzelt, and M. Wolfe, “Moving Forward from Project Failure: Negative Emotions, Affective Commitment, and Learning from the Experience,” Academy of Management Journal, vol. 54, no. 6 (2011), pp. 1229–60.

Staw, B. M., and J. Ross, “Knowing When to Pull the Plug,” Harvard Business Review, March/April 1987, pp. 68–74.

Wheatly, M., “Over the Bar,” PM Network, January 2003, pp. 40–45.

Yates, J. K., and S. Aniftos, “ISO 9000 Series of Quality Standards and the E/C Industry,” Project Management Journal, vol. 28, no. 2 (June 1997), pp. 21–31.

Zaitz, L., “Rail Car Deal Snags Tri Met for Millions,” Oregonian, December 14, 2008, p. 1, and January 7, 2009, p. D4.

Appendix 14.1

Project Closeout Checklist

Project Closeout Transition Checklist

Provide basic information about the project, including the following: Project Title—the proper name used to identify this project; Project Working Title—the working name or acronym that will be used for the project; Proponent Secretary—the secretary to whom the proponent agency is assigned or the secretary that is sponsoring an enterprise project; Proponent Agency—the agency that will be responsible for the management of the project; Prepared by—the person(s) preparing this document; Date/Control Number—the date the checklist is finalized and the change or configuration item control number assigned.

| Project Title: | ______________ | Project Working Title: | ______________ |

| Proponent Secretary: | ______________ | Proponent Agency: | ______________ |

| Prepared by: | ______________ | Date/Control Number: | ______________ |

Complete the Status and Comments columns. In the Status column indicate the following: Yes, if the item has been addressed and completed; No, if the item has not been addressed or is incomplete; N/A, if the item is not applicable to this project. Provide comments or describe the plan to resolve the item in the last column.

page 556

| Item | Status | Comments/Plan to Resolve |

|

| 1 | Have all the product or service deliverables been accepted by the customer? | ||

| 1.1 | Are there contingencies or conditions related to the acceptance? If so, describe in the Comments. | ||

| 2 | Has the project been evaluated against each performance goal established in the project performance plan? | ||

| 3 | Has the actual cost of the project been tallied and compared to the approved cost baseline? | ||

| 3.1 | Have all approved changes to the cost baseline been identified and their impact on the project documented? | ||

| 4 | Have the actual milestone completion dates been compared to the approved schedule? | ||

| 4.1 | Have all approved changes to the schedule baseline been identified and their impact on the project documented? | ||

| 5 | Have all approved changes to the project scope been identified and their impact on the performance, cost, and schedule baselines documented? | ||

| 6 | Has operations management formally accepted responsibility for operating and maintaining the product(s) or service(s) delivered by the project? | ||

| 6.1 | Has the documentation relating to operation and maintenance of the product(s) or service(s) been delivered to, and accepted by, operations management? | ||

| 6.2 | Has training and knowledge transfer of the operations organization been completed? | ||

| 6.3 | Does the projected annual cost to operate and maintain the product(s) or service(s) differ from the estimate provided in the project proposal? If so, note and explain the difference in the Comments column. | ||

| 7 | Have the resources used by the project been transferred to other units within the organization? | ||

| 8 | Has the project documentation been archived or otherwise disposed of as described in the project plan? | ||

| 9 | Have the lessons learned been documented in accordance with the Commonwealth Project Management guideline? | ||

| 10 | Has the date for the post-implementation review been set? | ||

| 10.1 | Has the person or unit responsible for conducting the post-implementation review been identified? |

page 557

Signatures

The signatures of the people below relay an understanding that the key elements within the Closeout Phase section are complete and the project has been formally closed.

| Position/Title | Name | Date | Phone Number |

Source: www.vita.virginia.gov/projects/cpm/cpmDocs/CPMG-SEC5-Final.pdf.

Case 14.1

Halo for Heroes II

You are a member of a project management practicum class. The major assignment for this class is to plan and implement a fund-raising project that will raise at least $1,500 and provide an opportunity to practice project management. You have joined a group of six students who have decided to organize an event based on the popular Halo video game. Your professor tells your group that they are in luck because another group did a similar project last year. He hands you a copy of their post-project audit.

Review the document and answer the following questions:

What are the two or three most valuable lessons you learned from this report and why?

What are one or two important questions/issues that are missing from their report that you wish were addressed? Explain why this information would be useful.

Briefly discuss the value of project audits based on this example. Imagine what it would be like if you did not have the audit.

Project Halo Audit

Objective: To raise at least $1,000 for the National Military Families Association by conducting a Halo video game tournament in Kleinsorge Hall on November 16 and 17.

Operation

See tournament information (below) for a detailed description on how the tournament was managed.

Risk Management

Through risk assessment we were able to identify and mitigate potential risks to the project. We were concerned with technical difficulties in setting up the gaming operations in the different classrooms. We did a trial run three days before the tournament in one of the classrooms to work out the mechanics of connecting consoles to the audio/video equipment in the room. This made setting up things on the first day of the tournament much easier. One surprise was that a few players failed to show up at designated times and we wished we had their cell phone numbers to contact them.

Outcomes

Our final contestant count was marked at 100 contestants, for a total of $1,000 in ticket sales. In addition, we received some cash donations from private sponsors, donated color fliers and equipment rental, 12 cases of Mountain Dew from Pepsi, and several smaller incentives from local businesses. The total valuation of all ticket sales and donated items was $3,113.43. We were unable to locate a business willing to sponsor any page 558large prizes; therefore, we had to purchase these out of our cash proceeds. After the purchase of all prizes and repayment of $100.00 to Prof. X for our seed money, our final net proceeds were $720.00. Despite not reaching our financial goal, the participants enjoyed the experience and we learned a lot about managing a project.

Lessons Learned

Don’t advertise specific prizes until you have obtained them. We assumed we could get a local retailer to donate the grand prize (Xbox 360) but ultimately we had to pay for it ourselves.

A multimedia marketing campaign is needed to reach the target audience. We utilized several different strategies to reach our target market, including a dedicated website and PayPal signup, a donation drive web page extended on this site, physical kiosk signups, the development and distribution of 2,500 color fliers, a MySpace page, a Facebook page, and an announcement on the College of Business website. We actually had contestants from as far away as Portland and Eugene.

Do a walk-through at least one day before the tournament.

Take time out to focus on the team. Team-building exercises we did in class, like “My group as a car,” helped us resolve interpersonal issues before they became serious.

Many of us felt the grand prize was a deterrent, with many prospective players opting out because they did not feel they were good enough at playing Halo to compete for such a lofty prize. In retrospect, we felt we could have done just as well by using donated prizes, like tickets for the local movie theaters and gift cards.

Next time we would set up a loser’s bracket so that players would have a chance to play against others with comparable ability and win prizes.

You need luck or personal contacts to secure big sponsorships. We had neither. However, we were surprised at how willing local businesses were to donate small prizes to the project.

Take advantage of the contacts you have on your team. Despite our extensive marketing campaign, roughly half of the participants were friends of ours. Your team’s social network provides both opportunities and limitations. For example, we had no active member in the Greek community on campus to organize a competition across houses.

Tournament Information

Welcome to the Halo for Heroes Tournament!

By entering this tournament, you agree to the following rules and guidelines.

Important!

This tournament is open to the public and we encourage open competition between all skill levels.

The entire tournament will be played on projected screens in dark rooms. You are more than welcome to bring your own controller to use during the tournament.

You will be able to make your custom profile on our system prior to playing, but we are unable to allow any outside memory to be loaded onto the systems due to time constraints and the “allow one to do it, allow all to do it” problem.

We hope you will have fun, and thanks for supporting Halo for Heroes and the National Military Families Association, Inc.

Reservations

This tournament is by online reservation only on our website, halo4heroes.110mb.com.

Space is limited. If you are unable to register and purchase a ticket online, please contact us. Once you have registered, an event manager will contact you by the e-mail address you provide upon registration within 24 hours. You will be e-mailed a ticket confirmation with an assigned play time, which you will need to enter the tournament. Please keep this, as it has important tournament information. If you are unable to play during the assigned time, please contact us immediately.

page 559

Arrival

Show up early! All players who enter the tournament must be ready to play by their respective times as noted on their ticket confirmation. Please arrive at least 15 minutes prior to the scheduled match time to check in. All players will need to check in at the front lobby of Kleinsorge Hall. All players who are late will forfeit their chance of participating in the tournament. We cannot guarantee parking around campus, so please take ample time to arrive at the event on time. (See the vicinity map.)

Tournament Sequence

All tournament rounds will consist of three matches played on Halo 3® among four individual players. Game style will be “Free for All Slayer” with 25 kills to win the match with a 10-minute time limit per match. All other game rules and options will be Halo 3® default settings. The player with the highest cumulative kill count of all the matches will advance to the next round. All the others will be eliminated from the tournament play. Round 1 will be conducted on Friday, November 16, and Rounds 2 and 3 will be conducted on Saturday, November 17. All play will be on projection screens. In order to judge the tournament, after a match is over the event managers will need to record the scores. For this reason, please be patient and wait until the event manager gives the okay to proceed with the next game. Below is a map schedule so you can begin practicing.

Halo 3® Map Schedule

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 |

| Last Resort | Guardian | The Pit |

| High Ground | Epitaph | Narrows |

| Snowbound | Isolation | Last Resort |

In the event that there is a tie, players will immediately play a single tie-breaking match. “Free for All Slayer” with five kills to win the tie-breaker with a five-minute time limit. The map for the tie-breaker will be “Construct.”

Non-Tournament Play

All players who did not receive a position in the tournament can still play! There will be an area set up for non-tournament play. There is a $3.00 charge for all entrants into non-tournament play.

Under-Age Players

Players under the age of 17 must be accompanied by a parent or guardian. The parent or guardian must also sign a Parental Release Authorization and bring it with the child to the event. Any unaccompanied persons who are under age will not be allowed to participate in the tournament.

General Rules

Do not damage any hardware and equipment. If you break it, you just bought it.

Conduct yourself in a respectful and supportive manner.

Unacceptable behavior will result in disqualification.

All disputes will be settled by the operators of the event.

Audience

If you have been eliminated and would like to stay and watch the tournament, you are welcome to do so. Family members and friends of contestants are also welcome to attend as an audience. We ask that all audience members be supportive and respectful of all contestants. We reserve the right to dismiss disruptive audience members from the premises.

page 560

Prizes and Raffles

The winner of the tournament will receive an Xbox 360. Other finalists will receive various prizes, including games, controllers, and gift certificates. All participants can participate in the event raffles that will be held at the event. Contributions to enter the raffles and the potential prizes will be disclosed at the event.

Refunds

This tournament is to benefit the American Military Families Association, Inc. There will be no refunds under any circumstances. Any dispute must be brought to the attention of the event managers for a decision.

CONTACT US

If you have any questions or concerns, contact one of the operators of the event or e-mail us at halo4heroes@hotmail.com. If you need to speak to someone immediately, please call 503-xxx-xxxx.

Thank you for your cooperation, have fun, and good luck!—Halo for Heroes

Case 14.2

Maximum Megahertz Project

Olaf Gundersen, the CEO of Wireless Telecom Company, is in a quandary. Last year he accepted the Maximum Megahertz project suggested by six up-and-coming young R&D corporate stars. Although Olaf did not truly understand the technical importance of the project, the creators of the project needed only $600,000, so it seemed like a good risk. Now the group is asking for $800,000 more and a six-month extension on a project that is already four months behind. However, the team feel confident they can turn things around. The project manager and project team feel that if they hang in there a little longer they will be able to overcome the roadblocks they are encountering—especially those that reduce power, increase speed, and use a new-technology battery. Other managers familiar with the project hint that the power pack problem might be solved but “the battery problem will never be solved.” Olaf believes he is locked into this project; his gut feeling tells him the project will never materialize and he should get out. John, his human resource manager, suggested bringing in a consultant to axe the project.

Olaf decided to call his friend Dawn O’Connor, the CEO of an accounting software company. He asked her, “What do you do when project costs and deadlines escalate drastically? How do you handle doubtful projects?” Her response was “Let another project manager look at the project. Ask, ‘If you took over this project tomorrow, could you achieve the required results, given the extended time and additional money?’ If the answer is no, I call my top management team together and have them review the doubtful project in relation to other projects in our project portfolio.” Olaf feels this is good advice.

Unfortunately, the Maximum Megahertz project is not an isolated example. Over the last five years there have been three projects that were never completed. “We just seemed to pour more money into them, even though we had a pretty good idea page 561the projects were dying. The cost of those projects was high; those resources could have been better used on other projects.” Olaf wonders, “Do we ever learn from our mistakes? How can we develop a process that catches errant projects early? More importantly, how do we ease a project manager and team off an errant project without embarrassment?” Olaf certainly does not want to lose the six bright stars on the Maximum Megahertz project.

Olaf is contemplating how his growing telecommunications company should deal with the problem of identifying projects that should be terminated early, how to allow good managers to make mistakes without public embarrassment, and how they all can learn from their mistakes.

Give Olaf a plan of action for the future that attacks the problem. Be specific and provide examples that relate to Wireless Telecom Company.

Design elements: Snapshot from Practice, Highlight box, Case icon: ©Sky Designs/Shutterstock