CHAPTER 2

Of Knives and Men

Cutting Ceremonies and Cuisine

At the same time that chefs in the employ of shoguns, elite warlords, and aristocrats in the fifteenth century were developing the arts of cooking and banqueting, they were also doing other, less conventional things with food in demonstrations called “knife ceremonies” (shikib ch

ch or h

or h ch

ch shiki) that produced inedible food sculptures. Studying inedible dishes like these might seem counterintuitive in a history of cuisine, which explains why most culinary historians of Japan mention them only in passing, if at all.1 However, the inedible foods described in this chapter and elsewhere in the book are the ones that most often became objects of intellectual curiosity and aesthetic evaluation at elite banquets in the late medieval and early modern periods. Consequently, they cannot be ignored in a study that identifies these traits as central to the definition of cuisine.

shiki) that produced inedible food sculptures. Studying inedible dishes like these might seem counterintuitive in a history of cuisine, which explains why most culinary historians of Japan mention them only in passing, if at all.1 However, the inedible foods described in this chapter and elsewhere in the book are the ones that most often became objects of intellectual curiosity and aesthetic evaluation at elite banquets in the late medieval and early modern periods. Consequently, they cannot be ignored in a study that identifies these traits as central to the definition of cuisine.

In a knife ceremony, a chef, with great formality and ritual, carved a large fish or game bird into a visual display similar to a flower arrangement (see plate 2). Knife ceremonies were one of several entertainments, like singing, storytelling, juggling, and the more serious Noh theater, performed to entertain the elite at banquets. For example, a text on etiquette by the ritual specialist Ise Sadayori (1529) for the Muromachi shoguns, S g

g Oz

Oz shi (ca. 1528), indicates that the shoguns witnessed chefs from the Shinji school carve a swan as part of annual celebrations of the new year at the mansion of the Hosokawa deputy shogun (kanrei) on the second day of the first month.2 In a similar annual rite in the Edo period, emperors viewed chefs from the Takahashi lineage carve a crane on the twenty-eighth day of the new year.3 Tea master End

shi (ca. 1528), indicates that the shoguns witnessed chefs from the Shinji school carve a swan as part of annual celebrations of the new year at the mansion of the Hosokawa deputy shogun (kanrei) on the second day of the first month.2 In a similar annual rite in the Edo period, emperors viewed chefs from the Takahashi lineage carve a crane on the twenty-eighth day of the new year.3 Tea master End Genkan (n.d.), in his manual on hosting daimyo and other high-ranking warriors, Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony (Cha no yu kondate shinan), published in 1676, explains that, “for occasions of a lord’s visit, a ‘thousand year crane’ is required,” indicating the appropriate animal and carving design for the h

Genkan (n.d.), in his manual on hosting daimyo and other high-ranking warriors, Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony (Cha no yu kondate shinan), published in 1676, explains that, “for occasions of a lord’s visit, a ‘thousand year crane’ is required,” indicating the appropriate animal and carving design for the h ch

ch nin s’ display.4 For these demonstrations, chefs left the behind-the-scenes world of the kitchen to showcase their skill with a knife, the principal tool of their trade.

nin s’ display.4 For these demonstrations, chefs left the behind-the-scenes world of the kitchen to showcase their skill with a knife, the principal tool of their trade.

Beginning in the late fifteenth century, chefs recorded the procedures for knife ceremonies in culinary texts (ry risho), private records containing the secrets of their occupation.5 These writings reveal the precision of movement required to execute a knife ceremony, suggesting that knife ceremonies could be appreciated as an art not simply for the various designs created from fish and fowl but also as a type of seated dance. Chefs, however, viewed knife ceremonies as more than simple entertainments: they describe the religious significance of these rites at great length in their culinary writings. The spiritual dimension of dismembering a fish or bird seems hard to imagine, given that, in premodern Japan, Buddhism provided ample arguments against taking life and Shinto warned of contamination from close contact with blood and death. Nevertheless, chefs interpreted the knife ceremony as a powerful way to cleanse any spiritual ill effects of taking animal life for food, not only from themselves and their patrons, who included high-ranking aristocrats and samurai, but also from the fish or bird that found itself on the cutting table.

risho), private records containing the secrets of their occupation.5 These writings reveal the precision of movement required to execute a knife ceremony, suggesting that knife ceremonies could be appreciated as an art not simply for the various designs created from fish and fowl but also as a type of seated dance. Chefs, however, viewed knife ceremonies as more than simple entertainments: they describe the religious significance of these rites at great length in their culinary writings. The spiritual dimension of dismembering a fish or bird seems hard to imagine, given that, in premodern Japan, Buddhism provided ample arguments against taking life and Shinto warned of contamination from close contact with blood and death. Nevertheless, chefs interpreted the knife ceremony as a powerful way to cleanse any spiritual ill effects of taking animal life for food, not only from themselves and their patrons, who included high-ranking aristocrats and samurai, but also from the fish or bird that found itself on the cutting table.

Knife ceremonies, due to their long history and prominence in elite food culture, are an important starting point for showing the connections between food and fantasy—raw ingredients and thinking about them—that were the ingredients for cuisine in premodern Japan. Before returning to this issue of cuisine, it will be useful to examine what knife ceremonies looked like and how premodern chefs understood their religious importance, as evidenced in their writings.

OF KNIVES AND MEN: THE PROFESSIONAL CHEF

Fans of sushi and sashimi, two dishes that are little more than sliced fish, know the degree to which slicing is crucial to modern Japanese cooking. Beginning with the gutting and boning of a fish and ending with the filleting of its select portions, the sushi chef needs to be familiar with an array of knives and their use. Part of the enjoyment of ordering sushi at a restaurant is sitting at the counter to watch the chef slice fish with a long knife. A chef’s performance at a “Japanese steak house” is even more theatrical. Seated around a grill, steak house customers can watch a chef dice steak and vegetables before their eyes, add a splash of oil to turn a pile of onions into a flaming “volcano,” and even juggle the pepper shakers.

Unlike the modern steak house chef who is a vaudeville version of a short-order cook, medieval chefs who performed knife ceremonies were not ordinary chefs: they were at the top of their occupation, employed only by the military and aristocratic elite. Called “men of the carving knife” (h ch

ch nin), the title made them synonymous with the chief tool of their trade, the h

nin), the title made them synonymous with the chief tool of their trade, the h ch

ch , a knife with a nine-inch blade used for filleting fish, birds, and other animals. Chefs used different knives to cut up vegetables. Ise Sadatake, a specialist in warrior ritual who came from a long family line of experts in that topic, clarifies this point and the close connection between h

, a knife with a nine-inch blade used for filleting fish, birds, and other animals. Chefs used different knives to cut up vegetables. Ise Sadatake, a specialist in warrior ritual who came from a long family line of experts in that topic, clarifies this point and the close connection between h ch

ch nin and their trademark tools:

nin and their trademark tools:

Ise’s comments appear in Teij ’s Miscellany (Teij

’s Miscellany (Teij zakki), a compendium on different points of warrior ritual and etiquette published posthumously in 1843. In a different passage from the same text, Ise notes, “In ancient times, all the noble houses, beginning with the court, had h

zakki), a compendium on different points of warrior ritual and etiquette published posthumously in 1843. In a different passage from the same text, Ise notes, “In ancient times, all the noble houses, beginning with the court, had h ch

ch nin appear at parties for the spectacle of carving a fish or a fowl.”7 Confucian scholar Hayashi Razan (1583–1657), in Record of the Knife (H

nin appear at parties for the spectacle of carving a fish or a fowl.”7 Confucian scholar Hayashi Razan (1583–1657), in Record of the Knife (H ch

ch shoroku), composed in 1652, indicates the degree of respect given h

shoroku), composed in 1652, indicates the degree of respect given h -ch

-ch nin. He lauds the past and present masters of this art, writing, “The people who study this Way deserve great praise.”8 Razan did not mean this as a compliment to anyone who worked in a kitchen: h

nin. He lauds the past and present masters of this art, writing, “The people who study this Way deserve great praise.”8 Razan did not mean this as a compliment to anyone who worked in a kitchen: h ch

ch nin came from respected lineages of cooks, such as the Takahashi house, who served the emperor, or the Sono branch of the Shij

nin came from respected lineages of cooks, such as the Takahashi house, who served the emperor, or the Sono branch of the Shij school, which supervised the shogun’s kitchen in the office of kitchen head (daidokorot

school, which supervised the shogun’s kitchen in the office of kitchen head (daidokorot ).9 Other prominent lineages included the Ikama, Shij

).9 Other prominent lineages included the Ikama, Shij , Shinshi (or Shinji), and

, Shinshi (or Shinji), and  kusa. These names spoke of entitlement and aristocratic or renowned warrior lineages, and they also designated a style of cooking dating to the fifteenth century or earlier.10 The Shij

kusa. These names spoke of entitlement and aristocratic or renowned warrior lineages, and they also designated a style of cooking dating to the fifteenth century or earlier.10 The Shij , for instance, traced their genealogy back to a branch house—appropriately called the “fish name branch” (uona no ry

, for instance, traced their genealogy back to a branch house—appropriately called the “fish name branch” (uona no ry )—of the northern branch of the Fujiwara family, which dominated government during much of the Heian period. The family’s founder, Shij

)—of the northern branch of the Fujiwara family, which dominated government during much of the Heian period. The family’s founder, Shij Ch

Ch nagon Fujiwara Yamakage (also known as Masatomo) (824–88), has been called the deity of Japanese cooking for allegedly inventing the cutting knife ceremony. Razan cited a famous story of the founder of the Sono house, Sonobett

nagon Fujiwara Yamakage (also known as Masatomo) (824–88), has been called the deity of Japanese cooking for allegedly inventing the cutting knife ceremony. Razan cited a famous story of the founder of the Sono house, Sonobett Ny

Ny d

d , also called Fujiwara Motofuji (1276–1316), who was able to carve a carp a different way every day for one hundred days.11 Razan likely read that story in Yoshida Kenk

, also called Fujiwara Motofuji (1276–1316), who was able to carve a carp a different way every day for one hundred days.11 Razan likely read that story in Yoshida Kenk ’s Essays in Idleness (Tsurezuregusa), a popular collection of literary sketches compiled around 1330. The latter work indicates that carving fish was recognized as an entertainment and skill since at least the early fourteenth century, and that there was a perception even then that the art dated back to earlier times.12

’s Essays in Idleness (Tsurezuregusa), a popular collection of literary sketches compiled around 1330. The latter work indicates that carving fish was recognized as an entertainment and skill since at least the early fourteenth century, and that there was a perception even then that the art dated back to earlier times.12

Up until Hayashi Razan’s time, h ch

ch nin might rightly be considered the only professional chefs, since commoners prepared their own foods and the earliest restaurants that served meals more complex than snacks did not appear until the 1680s.13 These restaurants were supervised by chefs called itamae, men who were literally “in front of the cutting board,” which may have been a position of respect but not one that rivaled the position of the h

nin might rightly be considered the only professional chefs, since commoners prepared their own foods and the earliest restaurants that served meals more complex than snacks did not appear until the 1680s.13 These restaurants were supervised by chefs called itamae, men who were literally “in front of the cutting board,” which may have been a position of respect but not one that rivaled the position of the h ch

ch nin, who worked for the elite.14 As the restaurant trade became more established in the Edo period, some h

nin, who worked for the elite.14 As the restaurant trade became more established in the Edo period, some h ch

ch nin taught their art to itamae and other wealthy commoners who wanted to learn their art in the same way that they studied the tea ceremony or flower arrangement. This allowed the heads of h

nin taught their art to itamae and other wealthy commoners who wanted to learn their art in the same way that they studied the tea ceremony or flower arrangement. This allowed the heads of h ch

ch nin lineages to become leaders and gain the title “family head” (iemoto) of “schools of cuisine.” As iemoto they were able to charge fees for lessons in the art of cutting, and to derive income from selling licenses that allowed students to practice new skills and wear formal trousers (hakama) of a different color at each successive rank.15 Townspeople who studied the knife ceremony followed in the footsteps of a few men of culture who had learned the art, including Hosokawa Y

nin lineages to become leaders and gain the title “family head” (iemoto) of “schools of cuisine.” As iemoto they were able to charge fees for lessons in the art of cutting, and to derive income from selling licenses that allowed students to practice new skills and wear formal trousers (hakama) of a different color at each successive rank.15 Townspeople who studied the knife ceremony followed in the footsteps of a few men of culture who had learned the art, including Hosokawa Y sai (1534–1610), a warlord and specialist in poetry and other cultural endeavors.16

sai (1534–1610), a warlord and specialist in poetry and other cultural endeavors.16

In summary, the historical legacy of the h ch

ch nin s’ knife ceremonies dwarfs that of the Japanese steak house chef, whose art was invented in the United States by a former professional wrestler and stock car driver named Rocky and dates only from the early 1960s. A rich and long historical legacy does not necessarily translate into worldly success today. Rocky Aoki’s Benihana restaurant chain, however, which began in 1964, has grown to ninety-six stores worldwide as of 2006 and has spawned countless imitators.17

nin s’ knife ceremonies dwarfs that of the Japanese steak house chef, whose art was invented in the United States by a former professional wrestler and stock car driver named Rocky and dates only from the early 1960s. A rich and long historical legacy does not necessarily translate into worldly success today. Rocky Aoki’s Benihana restaurant chain, however, which began in 1964, has grown to ninety-six stores worldwide as of 2006 and has spawned countless imitators.17

The art of the medieval chef is practiced only on very rare occasions in Japan today, such as at certain shrine festivals and at educational venues like the opening of a museum exhibit about food culture. Its current generation of leaders has inherited the long traditions of their art unevenly. One current family head of the Shij line, which divided into several branches long ago, is a former rock musician who played drums for the band Izumi Y

line, which divided into several branches long ago, is a former rock musician who played drums for the band Izumi Y ji and Spanky, and another is the head of a culinary school and owner of a Japanese restaurant in Kyoto, who purchased his title.18 This marks an unfortunate decline for an art that was popular in the medieval period to the point that actors in the comedic ky

ji and Spanky, and another is the head of a culinary school and owner of a Japanese restaurant in Kyoto, who purchased his title.18 This marks an unfortunate decline for an art that was popular in the medieval period to the point that actors in the comedic ky gen theater wrote several plays mocking it.19

gen theater wrote several plays mocking it.19

The decline is understandable. Unlike its medieval contemporaries—flower arrangement and the tea ceremony, which have successfully been adapted to modern life—an art that focuses on slicing animals on a wood table, transforming not only carp and sea bream but also protected species like crane into delicate slices, does not easily resonate with modern sensibilities. It is difficult to appreciate in the same way that a display of flowers or thick tea in a fine ceramic bowl can be appreciated.

Consequently, to understand the importance of this art in the history of Japanese food culture, we must try to recover the medieval sensibilities that sustained it. We can begin by looking more closely at what this art entailed by reading writings by h ch

ch nin dating from the fifteenth century through the early eighteenth century and a description by Ishii Taijir

nin dating from the fifteenth century through the early eighteenth century and a description by Ishii Taijir (1871–1954), in Encyclopedia of Japanese Cuisine (Nihon ry

(1871–1954), in Encyclopedia of Japanese Cuisine (Nihon ry ri taisei), published in 1898 and attributed to his father, Ishii Jihee (n.d.).20 Encyclopedia of Japanese Cuisine is an appropriate title for a work that covers the mythological origins and history of Japanese cuisine, providing genealogies of lineages of cooks, different styles of serving food, and an extensive glossary of important culinary terms, all illustrated with examples from medieval and early modern texts, making the book an important reference to this day. It is clear from Ishii’s description in this book, and from writings centuries older, that the knife ceremony was both an aesthetic practice and a powerful ritual considered able to reverse the bad karmic effects of killing and consumption of animal flesh—though limited to fish and game birds—by both liberating the animal and accruing longevity and merit for the chef and his patrons.

ri taisei), published in 1898 and attributed to his father, Ishii Jihee (n.d.).20 Encyclopedia of Japanese Cuisine is an appropriate title for a work that covers the mythological origins and history of Japanese cuisine, providing genealogies of lineages of cooks, different styles of serving food, and an extensive glossary of important culinary terms, all illustrated with examples from medieval and early modern texts, making the book an important reference to this day. It is clear from Ishii’s description in this book, and from writings centuries older, that the knife ceremony was both an aesthetic practice and a powerful ritual considered able to reverse the bad karmic effects of killing and consumption of animal flesh—though limited to fish and game birds—by both liberating the animal and accruing longevity and merit for the chef and his patrons.

KNIFE CEREMONIES AS ART

As is the case with many medieval art forms, it is difficult to distinguish the aesthetic from the religious in knife ceremonies since the two are closely intertwined, but there are two ways that knife ceremonies could be appreciated as art, as noted earlier. First, the chef’s skill with the blade and other movements can be described as a form of seated dance. Second, the displays that chefs created can be compared to sculpture or the art of flower arrangement.

Similar to a costumed dancer on stage, a chef performing a knife ceremony was dressed in a special outfit: a formal court dress with sleeves tied back and formal trousers (hakama). His set was a low wooden table called the manaita, which served as the ceremonial cutting board. His props were the single fish or bird that rested on the table and the long knife (h ch

ch ) and long metal chopsticks, called manabashi, used for carving.

) and long metal chopsticks, called manabashi, used for carving.

Tea master End Genkan sets the scene and describes props needed for cutting a crane in Guide to Menus for the Tea Ceremony, published in 1696.

Genkan sets the scene and describes props needed for cutting a crane in Guide to Menus for the Tea Ceremony, published in 1696.

End was usually verbose on a range of topics, but in this instance he deferred to the experts, the h

was usually verbose on a range of topics, but in this instance he deferred to the experts, the h ch

ch nin, who took responsibility for the proceedings once everything was in place.

nin, who took responsibility for the proceedings once everything was in place.

Like a master of the tea ceremony or a dancer, the chef followed codified movements, called kata, to create a seated dance that could be appreciated for its adherence to precedent and its grace. Ishii used the term kata in his descriptions of the “preliminary rites” (kakari) for the knife ceremony that occur before a fish or bird is carved. These he describes as a “set pattern [kata] of the Shij school.”22 In one kata called “inspecting the blade”(h

school.”22 In one kata called “inspecting the blade”(h ch

ch aratame) in Ishii’s descriptions, the h

aratame) in Ishii’s descriptions, the h ch

ch nin thrusts the knife several times outward with the blade upturned. The final time he performs this move, the h

nin thrusts the knife several times outward with the blade upturned. The final time he performs this move, the h ch

ch nin flips the paper wrapper for the knife off the table with the knife.

nin flips the paper wrapper for the knife off the table with the knife.

The term kata is one found in the performing and martial arts in Japan. In the dances of Noh theater, for example, the kata called sashikomi hiraki indicates taking a few steps forward and pointing with one’s fan (sashikomi), followed by a taking a few steps backward while spreading one’s arms (hiraki). Noh dances are created and preserved by combining different kata. Since they are a standardized vocabulary of gesture and movement, kata provide a degree of precision for the dancer. As Ishii Jihee notes about the kata for the preliminaries to the shikib ch

ch , “They cannot be contrived to suit one’s personal convenience,” recognizing that kata provide a degree of uniformity to movements, ensuring that traditional arts that utilize kata—whether Noh, the tea ceremony, or ceremonial cutting—maintain traditional patterns of movements. Like Noh, shikib

, “They cannot be contrived to suit one’s personal convenience,” recognizing that kata provide a degree of uniformity to movements, ensuring that traditional arts that utilize kata—whether Noh, the tea ceremony, or ceremonial cutting—maintain traditional patterns of movements. Like Noh, shikib ch

ch , then, is not an improvisatory art but one guided by specific motions, like the choreography of a Noh dance that an actor seeks to emulate accurately.

, then, is not an improvisatory art but one guided by specific motions, like the choreography of a Noh dance that an actor seeks to emulate accurately.

Just as in a traditional game of Japanese kickball (kemari) or a modern game of soccer, in which players cannot touch the ball with their hands, a h ch

ch nin could not touch the fish or bird on the table with his bare hands: he had to rely instead on his knife and chopsticks to manipulate and slice. The chef’s set movements incorporated dramatic flourishes, as when he brandished the long knife in the air. The performance also included aural punctuations equivalent to a Noh musician’s vocalizations (kakegoe), as when the chef struck his metal knife against the chopsticks. The following description from Ishii Jihee’s writings captures some of the ceremony’s drama:

nin could not touch the fish or bird on the table with his bare hands: he had to rely instead on his knife and chopsticks to manipulate and slice. The chef’s set movements incorporated dramatic flourishes, as when he brandished the long knife in the air. The performance also included aural punctuations equivalent to a Noh musician’s vocalizations (kakegoe), as when the chef struck his metal knife against the chopsticks. The following description from Ishii Jihee’s writings captures some of the ceremony’s drama:

This passage offers a sense of the theatricality of the knife ceremony. Broad movements of the blade, standing up from a kneeling posture, and creating gestures with the knife and chopsticks reminiscent of Buddhist sacred gestures called mudra were all devices to capture the audience’s attention. If these specific motions had meanings the way some Noh kata do, these were for left the audience to ponder, since Ishii did not offer any clues.

Turning to the second way to appreciate knife ceremonies—seeing them as reminiscent of the art of flower arrangement—chefs created stunning visual displays that evoked the seasons and were attuned to the setting and specific events. Secret Writings on Culinary Slicing (Ry ri kirikata hidensh

ri kirikata hidensh ), published in the mid-seventeenth century, provides names and illustrations for forty-seven different ways to cut carp, in the same way that writings on flower arrangement, calligraphy, and painting supplied models for students to copy, and audiences standards for making aesthetic judgments. The names of these are suggestive for the occasions they suited: Departing for Battle Carp (shutsujin no koi), Celebratory Carp (iwai no koi), Taking a Bride/Taking a Son-in-Law Carp (mukotori yometori koi), Flower Viewing Carp (hanami no koi), and Moon Viewing Carp (tsukimi no koi). Other names sound poetic: Snowy Morning Carp (yuki no asa koi), Long Life Carp (ch

), published in the mid-seventeenth century, provides names and illustrations for forty-seven different ways to cut carp, in the same way that writings on flower arrangement, calligraphy, and painting supplied models for students to copy, and audiences standards for making aesthetic judgments. The names of these are suggestive for the occasions they suited: Departing for Battle Carp (shutsujin no koi), Celebratory Carp (iwai no koi), Taking a Bride/Taking a Son-in-Law Carp (mukotori yometori koi), Flower Viewing Carp (hanami no koi), and Moon Viewing Carp (tsukimi no koi). Other names sound poetic: Snowy Morning Carp (yuki no asa koi), Long Life Carp (ch mei no koi), and Carp within a Boat (sench

mei no koi), and Carp within a Boat (sench no koi).24 In the case of the method Eternal Carp (ch

no koi).24 In the case of the method Eternal Carp (ch ky

ky no koi), the name is reflected in its sculptured form: according to Ishii’s description, the chef slices the carp’s tail into four pieces and then positions them to form a simplified version of the Chinese character for “eternal” (ch

no koi), the name is reflected in its sculptured form: according to Ishii’s description, the chef slices the carp’s tail into four pieces and then positions them to form a simplified version of the Chinese character for “eternal” (ch ; nagai).25 However, the correspondence between the shape of the sculpture and its name is not usually so apparent.

; nagai).25 However, the correspondence between the shape of the sculpture and its name is not usually so apparent.

To give a sense of what these fish sculptures looked like and how they were created, we can turn to Ishii’s directions for creating Eternal Carp:

Besides the theatrical gestures, like moving the fish’s severed head above the cutting board, the chef’s movements included visual reminders of the name of the piece in the way the chopstick and knife were held to form the Chinese character for eternal, which was also mirrored in the positioning of pieces of the fish to create the same character.

After the drama of the cutting ceremony, the fish could be appreciated as an object of temporary display, since it was not meant to be consumed. Once it was removed from display and brought back to the kitchen, it is conceivable that parts of the carp might wind up in a soup stock, but at that point it was no longer an art object. What happened to a fish after it was cut up for display did not merit discussion in culinary texts, in the same way that writings on flower arrangement did not concern themselves with discussing what to do with wilted flowers.

Important to the appreciation of certain fowl and fish as sculpture was their symbolic value; and, of all the varieties of fish and birds that a h ch

ch nin might cut up, carp was the most valued, reflecting its popularity as a food and as a symbol, especially in the medieval period.27 Carp was auspicious. Yoshida Kenk

nin might cut up, carp was the most valued, reflecting its popularity as a food and as a symbol, especially in the medieval period.27 Carp was auspicious. Yoshida Kenk writes, “The carp is a most exalted fish, the only one which may be sliced in the presence of the emperor.”28 Three centuries later, Hayashi Razan explained that carp was both a delicacy (bibutsu) and an auspicious food nicknamed a “gift to Confucius,” since the Chinese scholar received one when his son was born. Razan recounted the Chinese legend of a carp transforming into a dragon to climb a waterfall, which he cited as another reason for the high esteem for that fish.29

writes, “The carp is a most exalted fish, the only one which may be sliced in the presence of the emperor.”28 Three centuries later, Hayashi Razan explained that carp was both a delicacy (bibutsu) and an auspicious food nicknamed a “gift to Confucius,” since the Chinese scholar received one when his son was born. Razan recounted the Chinese legend of a carp transforming into a dragon to climb a waterfall, which he cited as another reason for the high esteem for that fish.29

The rationale for why fish and birds were considered suitable for the ceremonial cutting table, and other animals were not, is provided in the oldest text from the h ch

ch tradition, Shij

tradition, Shij School Text on Food Preparation (Shij

School Text on Food Preparation (Shij ry

ry h

h ch

ch sho), under the heading “Ranking Delicious Foods” (bibutsu j

sho), under the heading “Ranking Delicious Foods” (bibutsu j ge no koto):

ge no koto):

These bibutsu, “delicious things,” were ranked by virtue of the location associated with them, and their common characteristic is that they are all caught in the wild: none are domestic animals like the chicken, which never became a subject for the chef’s knife ceremony. Venison, wild boar, rabbit, and similar game meats were not used, although these were consumed in the medieval period. The h ch

ch nin restricted the animals used on the ceremonial cutting table to fish and “mountain” game birds, since these were aesthetically the most pleasing to dissect for display: boar and deer would have proved far too unwieldy on the cutting table.

nin restricted the animals used on the ceremonial cutting table to fish and “mountain” game birds, since these were aesthetically the most pleasing to dissect for display: boar and deer would have proved far too unwieldy on the cutting table.

THE RELIGIOUS MEANINGS OF THE KNIFE CEREMONY

The entertainment value of cutting up a carp or a beautiful crane in front of an audience might be easier to understand than the religious dimension of such a ceremony. The practitioners of the art of the knife ceremony, and their audience, who ranked among the highest social elite and included the emperor and shogun, evidently were able to rationalize the practice of carving dead animals. They appreciated it as an entertainment and for its spiritual significance, which is apparent in three areas: first, the magical values associated with the animals used; second, the religious symbolism of the utensils employed; and, third the ritual enacted. Collectively these allowed the chef not only to save himself and his patrons from negative karma associated with taking and consuming animal life but also to liberate the spirit of the animal served.

Culinary texts like Secret Writings on Culinary Slicing (Ry ri kirikata hidensh

ri kirikata hidensh ), which provide illustrations of different ways to cut fish and birds, also describe the multiple names of specific fins that affected their use in sympathetic magic. One fin, called the “babysitter fin” (ko mabori), was also known as the “water falling fin” (mizufuri no hire), “between the cypress fin” (sugisashi no hire), “the master’s fin” (shukun no hire), and the “pocket fin” (kaich

), which provide illustrations of different ways to cut fish and birds, also describe the multiple names of specific fins that affected their use in sympathetic magic. One fin, called the “babysitter fin” (ko mabori), was also known as the “water falling fin” (mizufuri no hire), “between the cypress fin” (sugisashi no hire), “the master’s fin” (shukun no hire), and the “pocket fin” (kaich no hire).31 Ise Sadatake mentioned that the same fin was also known as the “child prevention fin” (kotodome no hire). He placed great significance in this observation, warning that chefs avoided using that fin at wedding ceremonies since it was considered unlucky.32 Apart from a fish’s nutritional value, its body contained magical properties that a chef could manipulate for specific purposes. This suggests that the various ways of cutting carp mentioned earlier were designed not only to suit the aesthetic dimensions of an occasion but also to work a sympathetic magic to benefit that event. Unfortunately, culinary texts are mute on that topic, albeit Ise Sadatake’s remarks hint that such interpretations circulated orally.

no hire).31 Ise Sadatake mentioned that the same fin was also known as the “child prevention fin” (kotodome no hire). He placed great significance in this observation, warning that chefs avoided using that fin at wedding ceremonies since it was considered unlucky.32 Apart from a fish’s nutritional value, its body contained magical properties that a chef could manipulate for specific purposes. This suggests that the various ways of cutting carp mentioned earlier were designed not only to suit the aesthetic dimensions of an occasion but also to work a sympathetic magic to benefit that event. Unfortunately, culinary texts are mute on that topic, albeit Ise Sadatake’s remarks hint that such interpretations circulated orally.

Turning to the utensils for the cutting ceremony, we can learn their religious significance from several premodern sources, including the Complete Manual of Cuisine of Our School (T ry

ry setsuy

setsuy ry

ry ri taizen), by Shij

ri taizen), by Shij Takashima, published in 1714.33 This work is especially interesting for the meanings the author ascribes to the dimensions of the long metal chopsticks used in the cutting ceremony. He writes that they measure “one shaku [30.3 cm] and eight bu [approximately 2.4 cm], with the handles being four sun [12 cm] in length.” This seems mundane enough until the author describes them in detail:

Takashima, published in 1714.33 This work is especially interesting for the meanings the author ascribes to the dimensions of the long metal chopsticks used in the cutting ceremony. He writes that they measure “one shaku [30.3 cm] and eight bu [approximately 2.4 cm], with the handles being four sun [12 cm] in length.” This seems mundane enough until the author describes them in detail:

The measurements of the chopsticks are precise in their Buddhist references, according to this account, and speak to the four Devas, protectors that guard the four directions; the Lotus Sutra, thought by many to be the final word of Buddha on salvation; and the 108 mental defilements that afflict humanity. Numerology such as this could be expected in an object used in a religious ritual; clearly, the chopsticks are meant to serve as such.

Similar Buddhist associations surround the geometry of the knife; the same text notes that the knife “is eight sun [approximately 24 cm] from the neck [machi]. The length of the blade of eight sun refers to the eight-character phrase ‘form is emptiness and emptiness is form.’ It also represents the eight-branched sword of Shinto.” Here, the noted Buddhist aphorism from the Heart Sutra about the relationship between relative and absolute existence, form and emptiness, is joined to a reference to the eight-branched sword (yatsuo no ken) in Shinto. The ritual use of the knife is clear from the next passage: “This is the knife that invites the presence of the divine [h ch

ch kanj

kanj ].” Thus the ceremonial knife not only symbolized religious truths but was also a tool like a shaman’s wand used to summon divinities to the ceremony. These divinities were not conjured to feast at the sacrifice, for it is made clear in the description of the cutting board that the animal was liberated after death for salvation in a Buddhist paradise.

].” Thus the ceremonial knife not only symbolized religious truths but was also a tool like a shaman’s wand used to summon divinities to the ceremony. These divinities were not conjured to feast at the sacrifice, for it is made clear in the description of the cutting board that the animal was liberated after death for salvation in a Buddhist paradise.

Shikib ch

ch writings—beginning with the earliest, the 1489 Shij

writings—beginning with the earliest, the 1489 Shij School Text on Food Preparation—note that certain places on the cutting table had names. These were not drawn on the actual table but were instead added to diagrams of these tables drawn from the perspective of a h

School Text on Food Preparation—note that certain places on the cutting table had names. These were not drawn on the actual table but were instead added to diagrams of these tables drawn from the perspective of a h ch

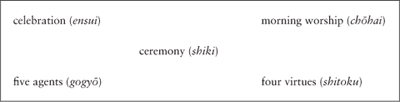

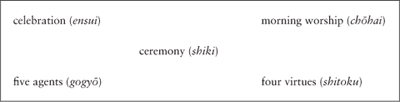

ch nin facing the table. Under the heading “Traditions of the Ceremonial Cutting Table,” the Complete Manual of Cuisine of Our School defines the names of the four corners.

nin facing the table. Under the heading “Traditions of the Ceremonial Cutting Table,” the Complete Manual of Cuisine of Our School defines the names of the four corners.

TABLE 1 LOCATIONS ON A CEREMONIAL CUTTING TABLE

While the knife was an instrument for summoning divine forces, the cutting board, according to this description, already had supernatural forces residing in it, making it akin to a sacred statue or some other venerated object housing a divinity. Information on how these various agents were harmonized together in the context of a cutting ceremony appears to have been restricted to oral instructions, which we do not have, but we do know that the names provided a mnemonic function for learning the art of knife ceremonies. Ishii, for example, often directs his readers to perform certain actions over specific named corners, as we saw earlier in his directions for carving an Eternal Carp.

Like the knife and chopsticks, the cutting table also had Buddhist symbolism integral to its use for liberating the animals prepared on it. According to the early-to-mid-seventeenth-century Ry ri kirikata hidensh

ri kirikata hidensh , the ceremonial cutting board was a manifestation of Amida Buddha’s Pure Land, as indicated by its geometry.

, the ceremonial cutting board was a manifestation of Amida Buddha’s Pure Land, as indicated by its geometry.

The description adds that Amida also manifested as the Shinto deity of longevity, Taka My jin. The cutting board invoked the divine presence of Amida-Taka My

jin. The cutting board invoked the divine presence of Amida-Taka My jin in its symbolism and in the ceremonies occurring on it. The reason for this invocation becomes clear when following the ritual actions that occurred prior to the cutting ceremony.

jin in its symbolism and in the ceremonies occurring on it. The reason for this invocation becomes clear when following the ritual actions that occurred prior to the cutting ceremony.

The liberation of the animal took place at the culmination of what were called “preliminaries” (kakari), the ceremony performed before a fish or bird was carved.37 Ishii described the preliminaries for cutting a carp in the style of the Shij school. They consisted of fifteen steps and involved a series of complicated movements to formally purify the cutting board and prepare the fish or game bird for dissection. The preliminaries culminated in step fourteen, when the chef lifted the animal upward using the knife and chopsticks before dropping it onto the board as described in Ishii Jihee’s account.

school. They consisted of fifteen steps and involved a series of complicated movements to formally purify the cutting board and prepare the fish or game bird for dissection. The preliminaries culminated in step fourteen, when the chef lifted the animal upward using the knife and chopsticks before dropping it onto the board as described in Ishii Jihee’s account.

The phrase “saved carp” (sukui koi), which appears twice in phonetics in Ishii’s description, presents a challenge to interpret. There are two possible meanings for the Japanese word. One is “to scoop,” as in the way small fish might be scooped up with a net or a basket. Another meaning is “to rescue,” which would be ironic, given the fact that if the carp had been rescued it would not find itself on a cutting board in the first place. However, this second meaning of sukui has religious connotations similar to the English word salvation. In a Buddhist context, one is saved from hell and other realms of rebirth either through enlightenment or through the grace of Amida Buddha, who allows devotees to escape the cycle of reincarnation after death by being born into his Pure Land paradise. The knife ceremony functioned as a way for Amida to save fish from rebirth, since they would be unable to enter his Pure Land by invoking his divine name the way humans can. It was too late, though, for the dead fish or bird to benefit from Amida’s manifestation as the Shinto deity Taka My jin, who was responsible for longevity: that blessing was meant instead for the participants in the ceremony, the h

jin, who was responsible for longevity: that blessing was meant instead for the participants in the ceremony, the h ch

ch nin and his audience, who would by Buddhist reasoning suffer the karmic consequences of a shortened life due to their killing and consumption of animal flesh.

nin and his audience, who would by Buddhist reasoning suffer the karmic consequences of a shortened life due to their killing and consumption of animal flesh.

In summary, the ceremonial cutting ritual functioned as a type of karmic prophylactic for the chef, who regularly took the lives of creatures, and for the people who consumed his meals. This provided a justification for cutting ceremonies, if not a rationale for persisting in hunting and dining on animal flesh, since these could be viewed as a Buddhist “skillful means” (upaya) to bring salvation to animals that the latter could not otherwise obtain. Significantly, the salvation of the carp or other animal occurred at the climax of the preliminaries, when its body rose with the h ch

ch nin ’s assistance before being unceremoniously dropped onto the cutting board, with the h

nin ’s assistance before being unceremoniously dropped onto the cutting board, with the h ch

ch nin theatrically spreading his arms and hitting the board with his knife for added emphasis. This change in the handling of the carp marked the moment the spirit of the carp left to enter Amida’s Pure Land, leaving only the body, which could be safely cut up without karmic repercussions.

nin theatrically spreading his arms and hitting the board with his knife for added emphasis. This change in the handling of the carp marked the moment the spirit of the carp left to enter Amida’s Pure Land, leaving only the body, which could be safely cut up without karmic repercussions.

That a dead carp could bring bad luck to an event like a wedding simply by the way it was prepared indicates that its body retained a degree of magical power even after its spirit departed for the Pure Land. With the preliminaries completed, the chef manipulated that power by gradually slicing away the mundane body of the fish and creating a new body in symbolic form. Since this reconstituted body was not offered to anyone to eat, it was “sacrificed,” an act anthropologist Daniel Miller has defined as “the violent destruction of some otherwise useful resource in an act of expenditure.” This destruction was not entirely wasteful, in the sense that something was gained. Miller explains, “Sacrifice transforms consumption into devotion.”38 In the case of the knife ceremony, the animals were not sacrificed directly to a deity, yet neither did they become sashimi for human consumption. Instead, in shapes such as Taking a Son-in-Law Carp and Long Life Carp, fish and fowl carved in knife ceremonies embodied culinary rules for turning the gutting of animal flesh into an aesthetic and spiritual practice and for judging the outcome. Cuisine in premodern Japan provided rules for imbuing food with artistry, magic, and whatever else provoked the intellect, and those dishes that were not consumed—such as those created in knife ceremonies—were the most clearly associated with transcendent concepts. This observation is equally true of the foods served at elite banquets, examined in the next chapter.

ch

ch or h

or h ch

ch shiki) that produced inedible food sculptures. Studying inedible dishes like these might seem counterintuitive in a history of cuisine, which explains why most culinary historians of Japan mention them only in passing, if at all.1 However, the inedible foods described in this chapter and elsewhere in the book are the ones that most often became objects of intellectual curiosity and aesthetic evaluation at elite banquets in the late medieval and early modern periods. Consequently, they cannot be ignored in a study that identifies these traits as central to the definition of cuisine.

shiki) that produced inedible food sculptures. Studying inedible dishes like these might seem counterintuitive in a history of cuisine, which explains why most culinary historians of Japan mention them only in passing, if at all.1 However, the inedible foods described in this chapter and elsewhere in the book are the ones that most often became objects of intellectual curiosity and aesthetic evaluation at elite banquets in the late medieval and early modern periods. Consequently, they cannot be ignored in a study that identifies these traits as central to the definition of cuisine. Genkan (n.d.), in his manual on hosting daimyo and other high-ranking warriors, Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony (Cha no yu kondate shinan), published in 1676, explains that, “for occasions of a lord’s visit, a ‘thousand year crane’ is required,” indicating the appropriate animal and carving design for the h

Genkan (n.d.), in his manual on hosting daimyo and other high-ranking warriors, Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony (Cha no yu kondate shinan), published in 1676, explains that, “for occasions of a lord’s visit, a ‘thousand year crane’ is required,” indicating the appropriate animal and carving design for the h kusa. These names spoke of entitlement and aristocratic or renowned

kusa. These names spoke of entitlement and aristocratic or renowned  )—of the northern branch of the Fujiwara family, which dominated government during much of the Heian period. The family’s founder, Shij

)—of the northern branch of the Fujiwara family, which dominated government during much of the Heian period. The family’s founder, Shij nagon Fujiwara Yamakage (also known as Masatomo) (824–88), has been called the deity of Japanese cooking for allegedly inventing the cutting knife ceremony. Razan cited a famous story of the founder of the Sono house, Sonobett

nagon Fujiwara Yamakage (also known as Masatomo) (824–88), has been called the deity of Japanese cooking for allegedly inventing the cutting knife ceremony. Razan cited a famous story of the founder of the Sono house, Sonobett